Social Commentary in The Office

The mockumentary sitcom series known as The Office is inarguably one of the most influential television series to date. In the United States, The Office ended in 2013, but it continues to be wildly popular. Its unique, satirical character sketches have made it the subject of dozens if not hundreds of articles, videos, and essays analyzing everything from the cinematography to the way it approaches current events. Probably the most detailed and thorough analysis of The Office is a series of essays and an ebook written by Venkat Rao for his blog Ribbon Farm. Rao dubs his theory the Gervais Principle, after Ricky Gervais, who created the original British version of The Office 1. But just how relevant is the Gervais Principle today, where did it come from, and what is The Office really trying to say about society?

The Gervais Principle

As previously noted, the Gervais Principle is a term coined by blogger Venkat Rao to describe how the workplace in The Office functions. Rao further goes on to state that real workplaces function in exactly the same way, and provides readers with numerous tips for how to negotiate such workplaces, allegedly based on the characters and plot points of The Office. He devotes six long essays to expounding upon his new principle, and caps everything off with an ebook that can be purchased on Amazon. Ultimately, Rao attempts to explain his views about how the universe is structured and understood using The Office characters, most especially the human resources representative Toby Flenderson 2. Despite its name, the principle has little to do with the original British Office or the Gervais character David Brent. Instead, nearly all the examples Rao uses to support his points come from the US series.

Axiomatic to the Gervais Principle is the idea that there is no such thing as a truly functional organization, but only varying degrees of dysfunction, such that

[W]hile most management literature is about striving relentlessly towards an ideal by executing organizational theories completely, this school […] would recommend that you do the bare minimum organizing to prevent chaos, and then stop. Let a natural, if declawed, individualist Darwinism operate beyond that point. […] It may be horrible, but like democracy, it is the best you can do.

3

Along similar lines, every organization is populated by people that Rao labels as Sociopaths, Clueless, and Losers. He goes into some detail about how each of them work:

The Sociopath (capitalized) layer comprises the Darwinian/Protestant Ethic will-to-power types who drive an organization to function despite itself. […] The Losers are not social losers (as in the opposite of “cool”), but people who have struck bad bargains economically–giving up capitalist striving for steady paychecks.

[…]

The Clueless are the ones who lack the competence to circulate freely through the economy (unlike Sociopaths and Losers), and build up a perverse sense of loyalty to the firm, even when events make it abundantly clear that the firm is not loyal to them.

4

Simply put, the Gervais Principle is predicated on the idea that loyalty is for suckers, and everyone in the business world should be as self-centered and ruthless as possible. Perhaps this idea was always present in business to varying degrees, but the Principle leaves no room for someone to be a decent human being–the only question is whether they are smart enough to get what they want and avoid being played for a fool (it is telling that Rao has since published another ebook titled Be Slightly Evil 5).

Although Rao is immensely thorough about how the Gervais Principle operates and what its implications are, he is mysteriously silent on the reasons why it exists. Crucially, Rao himself acknowledges that the Clueless archetype is a relatively recent development. Its prototype was the Organization Man, a term coined in the 1950’s by William “Holly” Whyte in his book of the same name, which Rao often references. Clearly, something happened in the intervening decades to turn the Organization Man into the Clueless man, but Rao never explores what that something might be.

What’s even more interesting is that Rainn Wilson, who plays Dwight Schrute in the US Office, noted in an interview that there is a clear generation gap in how The Office is received. Generally speaking, older people find the characters in The Office gross and unlikable, whereas younger viewers love them 6. This provides even more evidence that a cultural change in the twentieth century paved the way for the Gervais Principle–and, ultimately, the plot of The Office. The rest of this essay will be an exploration of what that cultural change is and what the implications are, both for The Office and for society in general.

The Office at a Glance

The Office began its life as a British sitcom series created by Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant. This series, which was one of the first serialized mockumentaries to be produced for television 7, follows the adventures of David Brent, a stupid and socially inept middle manager at a paper company called Wernham-Hogg. Despite its stripped-down appearance and gloomy tone, the series was a massive critical and commercial success, and eventually spawned adaptations in many different countries. The most famous such adaptation, from the United States, would run for a total of nine seasons between 2005 and 2013. Several adaptations were also made outside of the English-speaking world, including countries such as India and Israel 8.

In the United States, The Office takes place in Scranton, a small city in northeast Pennsylvania. The central characters are Michael Scott, the regional manager of the Dunder-Mifflin Paper Company, and his underling Dwight Schrute, both of whom are extraordinarily stupid and gullible. Throughout the series, the two of them devise numerous strategies to keep the company running and advance in their career, but usually end up creating more problems than they solve.

The Sociology Behind The Office

The roots of the societal malaise depicted in The Office likely began with the Industrial Revolution. Industrialization caused the production of goods and services to shift from self-contained home workshops to large factories and corporations. This cultural change made goods and services much cheaper and more accessible, but it also increasingly transformed workers into cogs in a capitalist machine and made work itself more tedious, repetitive, and depressing.

It was also around this time that scientific and technological principles began to be applied to social relationships and family life. For instance, mothers were no longer expected to trust their instincts, or the advice of their grandmothers, to determine how to raise their children, but were instead meant to put their trust in parenting books produced by “experts.” The result of all these changes was a sacrifice of “organic” connections and communities all around, as the paid marketplace took over more and more aspects of life 9. Tim Canterbury, one of the main characters in the British Office, notes ruefully that he spends more time with his work colleagues, whom he has nothing much in common with other than their workspace, than with his own family.

After World War II, some social commentators began noticing even more disturbing trends. In the mid-1950’s, Whyte’s The Organization Man sounded the alarm about a spirit of conformity that Whyte feared was taking over the business world and squeezing out its best talent. Whyte was particularly disturbed by companies’ use of personality tests in their hiring process, which they used to pick the “best” (that is, the most pliable and gregarious) candidates, and even went so far as to provide jobseekers with suggestions for how to “cheat” on the tests 10.

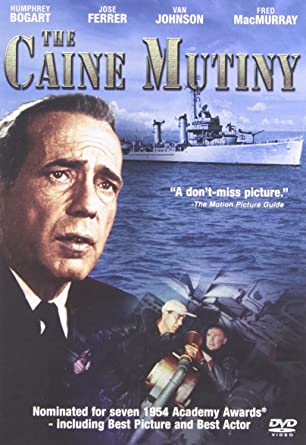

At one point in The Organization Man, Whyte references a popular post-World War II novel known as The Caine Mutiny. This story features a young navy man who is forced to pilot a ship under the direction of a captain named Queeg, whom Whyte describes as “a bully, a neurotic, a coward, and what is to be most important of all, an incompetent 11“–all traits that fit Michael Scott to a tee. Eventually, when the ship encounters a big storm, the hero relieves Queeg of his post so he can sail the ship to safety. However, this is later revealed to have been the wrong choice, as there is allegedly no excuse for disobeying or relieving even a terrible captain. This attitude is exactly how Michael’s staff treat him–and, seemingly, how the audience of The Office is meant to view him as well. Interestingly, the original British Office seems to take the opposite view: eventually, David is fired for incompetence, and the company ends up being better for it.

Most importantly of all, Whyte noted that Organization Men were obsessed with group work, compromise, and solving problems in teams. The supremacy of the group, in the form of meetings and conferences that nobody wants to be in, is a regular feature of both the US and the UK Offices. As it would happen, however, this love of “group work” would not stop at the office, but would eventually pervade all of society.

Group Mentality for Kids

In 1971, when Michael Scott would have been about six years old, the famous philosopher Ayn Rand published a collection of essays, including one titled The Comprachicos. In this essay, she outlined the ways in which she believed the education system in the US was failing its children. Of particular concern to her was the tendency of many parents to send their children to “Progressive nursery schools”–that is, day cares 12. According to Ayn Rand, young children are programmed to learn from their elders above all else, but that a progressive nursery school, by its very nature, does not permit this.

At the age of three, when his mind is almost as plastic as his bones, when his need and desire to know are more intense than they will ever be again, a child is delivered–by a Progressive nursery school–into a pack of children as helplessly ignorant as himself. He is not merely left without cognitive guidance–he is actively discouraged from pursuing cognitive tasks. He wants to learn; he is told to play. Why? No answer is given. He is made to understand […] that the most important thing in this peculiar world is not to learn, but to get along with the pack. Why? No answer is given.

13

Nor does the essay stop with criticizing day care. It argues that the entire system of education, from cradle to college, is designed to inculcate conformity at every turn. One group of young people that Ayn Rand singles out are the nonconformist “thinking” children, the “heroic little martyrs,” in her words, who are bullied for refusing to go along to get along 14.

At the time The Comprachicos was written it was largely speculative. However, the intervening decades have thrown up evidence that would seem to vindicate its thesis in full. Indeed, things have only gotten worse as day care and divorce have become ubiquitous and children spend more and more time associating with peers rather than family. In 1997 (when the likes of Jim, Pam, and Ryan would have been in high school), a Jewish mother named Dana Mack described a public school system whose purpose was not to educate the children, but to bring them all to the same level and pressure them to conform. At one point, Mack describes a high school in rural Pennsylvania whose students were forced to take a personality assessment similar to those described by Whyte decades before. One question on this assessment asked the students what it would take to convince them to join an exclusive club at their school. According to Mack,

State examiners wanted students to say they would join the club if their “best friend” or the “most popular students” were in it, for these responses would indicate what they regarded as a positive disposition to social conformity and peer commitment!

15

Meanwhile, the subject of day care was revisited in 2001 by Kay S. Hymowitz, in an article titled “Fear and Loathing at the Day-Care Center.” By this point, the “anti-cognitive” model of day care that attracted so much ire from Ayn Rand had long since been replaced by a newer model that stressed academic and cognitive achievement–even in infants. Observing that children raised in day care were much more likely to behave in aggressive and inappropriate ways, Hymowitz suggested that the children lose out when their parents are not there to socialize them. She explained:

[T]he child does not simply learn self-control the way he learns to develop his fine motor skills. He must internalize the moral requirements of his culture, make them part of his very nature and identity, so that they feel as natural as breathing.

Of course, there are any number of ways this can happen. In many pre-modern societies, children learned to obey society’s rules because they feared the rod. […] But most Western bourgeois societies, especially ours, discipline children through love, a huge psychic undertaking. Out of love, parents, particularly mothers, devote themselves to nurturing the child’s individual talents, interests, and temperament. Meanwhile, the child’s desire to please the adored mother and his fear of losing her love when she disapproves of him make him want to behave as she wishes him to. […] [Children who spend a lot of time away from their mothers] have not had the opportunity to develop with sufficient intensity the bonds that anchor the bourgeois conscience.

16

Advocates of day care often claim that children who spend their formative years there will be more independent and assertive growing up, and that these traits will help them get better jobs later on. Hymowitz sarcastically responds that, even if such a claim were true, it leads to a mentality in which “As long as the child grows up to be a high-achiever […] is it really so important that she is obnoxious or even vaguely immoral 17?” As it turns out, this applies to much of the Office cast, particularly its younger members.

The Amoral Office

On at least one point Rao is correct: the characters in The Office (at least in the United States) are truly terrible people. Not a single episode goes by without at least one of them doing something selfish, manipulative, cruel, offensive, or just plain stupid, and nobody is immune. Moreover, the cast members who are superficially pleasant or “nice” are just as self-centered and amoral as the ones who are more obviously ornery. This is because moral virtue requires far more than simply being nice to people. A truly virtuous person is one who can be counted upon to do the right thing even when it is difficult or uncomfortable, and that is something that almost none of the characters in The Office are capable of. The best of them can be genuinely kind and selfless when they want to (albeit cruel and self-centered the rest of the time); the rest cannot do even this much.

C.S. Lewis, the famous Christian writer, identified four traits–prudence, temperance, justice, and fortitude–that he called “cardinal virtues,” under the assumption that people all over the world can be trusted to value them 18. Most of the cast members in The Office can, at best, do a few of these, on an inconsistent basis. Michael, in particular, is utterly devoid of all of them. Virtually everything he does is foolish, self-indulgent, dishonest, cowardly, or some combination of the four. He is so utterly craven and self-absorbed that, in the Season Five episode “Golden Ticket,” he sets up Dwight to take the fall for a project that he came up with (even raising the prospect of Dwight getting fired) when he fears it will be unsuccessful, only to try to take credit back away from Dwight once it becomes clear that David Wallace, Dunder-Mifflin’s dashing chief financial officer, actually loved the idea!

The characters likely get away with their bad behavior because of something YouTuber Jesse Tribble pointed out in his analysis of the British Office:

It’s easier to let things go because confronting someone can be just as disruptive. It’s the equivalent of spanking a child in public.

19

In other words, the cast of the US Office operate under the assumption that, as long as they keep their cruelty within a certain limit, their target will keep quiet for fear of making an even bigger scene and causing more problems. This strategy allows them the freedom to indulge in plenty of workplace bullying. Michael’s problem is that he has no understanding of where the limit is, and so he expects people to just “get over” extremely serious provocations whose consequences are obvious to everyone. A clear example of this can be seen in the “Fun Run” episode, when he strikes Meredith with his car. Generally speaking, though, the characters’ favorite targets are those who are obvious misfits (like Dwight), too weak and timid to stick up for themselves (like Toby), or a combination (like Gabe and, arguably, Andy).

High School Never Ends

In Season Three, a preppy salesman named Andy Bernard transfers to Scranton from Stamford, Connecticut. It isn’t long before he starts adding his own brand of mayhem to the proceedings. Rao characterizes Andy as an overgrown teenager whose only aim in life is to be accepted by the “cool kids 20.” This is true as far as it goes, but it would be a mistake to assume that Andy is the only one who feels this way.

The reality is that the social world at Dunder-Mifflin’s Scranton branch is very much like that of a high school. There are “popular” people (the clearest example being Jim Halpert) whom everyone wants to associate with, and then there are “unpopular” people whom the others feel entitled to bully and dominate. Tellingly, numerous commentators have likened Jim’s pranks on Dwight to those of a jock bully picking on a nerd 21 22.

Some of the characters even go so far as to form exclusive clubs, or “cliques.” One of the most prominent of these clubs is the Party Planning Committee, which, as its name suggests, is in charge of coordinating special events. In Season Three, Angela refuses to allow Karen, another transfer from Stamford, to make any changes to her plans for the annual Christmas party. Karen goes to Pam and the two of them respond by planning a separate party of their own. Then, like two dueling groups of mean girls, the committees plan their separate parties with each trying to outdo the other. There is also the Finer Things Club, which Pam, Toby, and Oscar form in order to have a space to organize tea lunches and discuss classic novels amongst themselves. Nobody else is allowed to join without their express permission. It’s important to note that Rosalind Wiseman, an educator who specializes in the social worlds of young people, expressly warns parents against allowing their children to form exclusive clubs and make other kids feel unwelcome 23.

In other words, the social dynamics of the US Office are almost exactly like those of a middle school or high school, complete with cliques, popularity contests, and bullying. The problem, of course, is that the people involved have left high school behind a long time ago and should know better.

How (Not) to Make Friends

In The Comprachicos, Ayn Rand at one point observes:

Prompted by loneliness, unable to know that the pleasure one finds in human companionship is possible only on the grounds of holding the same values, a child may attempt to reverse cause and effect: he places companionship first and tries to adopt the values of others […] in the belief that this will bring him friends. The dogma of conformity to the pack encourages and reinforces his moral self-abnegation. […] He alternates between abject compliance with his friends’ wishes, and peremptory demands for affection- he becomes the kind of emotional dependent that no friends of any persuasion could stand for long.

24

What’s interesting about this paragraph is that it could have been written specifically with Michael Scott in mind. Michael spends nearly the entire series trying to impress other people with his alleged humor, charm, kindness, or whatever he thinks will make him most liked. If a difficult decision must be made, he tries to pass the buck to someone else–usually Dwight–as in the episode “Health Insurance” from Season One. It’s also revealed that when Michael was a child, he stated that he wanted to have one hundred children so that he would have one hundred friends, and none of them could say “no” to being his friend. As he himself puts it: “Do I need to be liked? Absolutely not! I like to be liked. I enjoy being liked. I have to be liked.”

This same problem also applies to Andy. As previously stated, Andy has many traits in common with a high-schooler who wants to sit with the cool kids. When he’s first introduced, it becomes clear that he will say and do just about anything to get in someone else’s good graces. In later seasons, he becomes a manager, but proves to be terrible at the job. The reason is obvious: Andy is used to thinking of his staff as his friends, and so he never disciplines them or imposes any consequences when they step out of line.

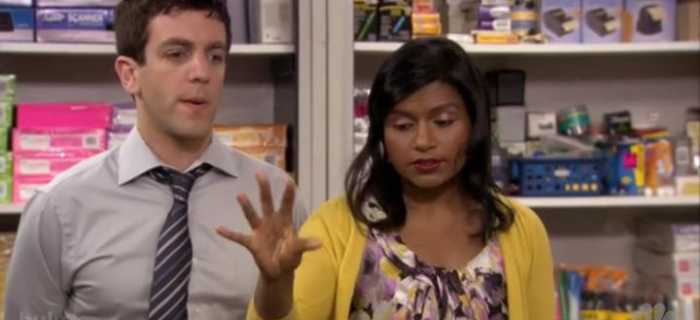

Ayn Rand then continues more ominously: “But the nameless emotion growing in [a child’s] subconscious, never to be admitted or identified, is hatred for people 25.” Does Michael truly hate people, though? He certainly claims that he loves his staff, and thinks of them as his family, but his actions suggest otherwise. Most notably, the offensive jokes he makes at the expense of his minority staff members happen far too often to be entirely innocent. Even after the disastrous “Diversity Day” episode, in which he goes too far and is slapped by Kelly Kapoor, he continually makes fun of his staff for any traits that might make them feel isolated or inferior. Michael is also relentlessly cruel and abusive to Toby, often for seemingly no other reason than that Toby gets in the way of whatever Michael feels like doing. At one point Michael even goes so far as to admit that, if given the choice, he would rather shoot Toby than either Osama bin Laden or Adolf Hitler!

As for Andy, he at one point openly admits to hating people for the demands they place on him. It’s notable as well that when Andy feels cornered, he tends to extricate himself by throwing a tantrum, seemingly oblivious to the impact of his behavior on others. What makes Andy’s case particularly interesting is that he was likely groomed to be an Organization Man all his life by his high-achieving parents. Presumably, they were the ones who pushed him to get into Cornell (a “decent” school) and get a “real” job. However, the one thing Andy genuinely seems to care about is his music. At the end of the series he attempts to leave Dunder-Mifflin for good in order to become a professional musician, but by then it’s too late. The really sad thing is that if Andy had been truly nurtured and supported in his musical interests from a young age, he might very well have become, if not a professional musician, at least a halfway-decent one.

The “Adjusted” Child, All Grown Up

What happens to Rand’s “adjusted” children when they reach maturity? Rand herself took a dim view of such people, insisting that they had “accepted the approval of the pack and/or power over the pack in exchange for surrendering their judgment 26.” Three decades later, in his book Day Care Deception, Brian C. Robertson echoes her words:

A collective setting that rewards group-oriented compliance […] encourages social skills of manipulation, whether they are devices to seek attention, violent reactions to not getting one’s way, or surface conformity and obedience to win approval. It does not encourage the development of a sense of self with internalized rules of conduct that transcend the environment–an inherent sense of right and wrong independent of the [person’s] immediate desires.

27

Enter Jim Halpert. Jim is a salesman at Dunder-Mifflin, loosely based on the British senior sales representative Tim Canterbury. He is depicted as a cool, athletic everyman that the audience is meant to relate to, and he often takes on a leadership role in activities with his colleagues. Underneath it all, though, Jim is a pretty awful person.

The clearest example of Jim’s mean streak is the pranks that he pulls on Dwight. He shares this trait with Tim, who would pull mostly-harmless pranks on his annoying coworker Gareth. However, in Jim’s case, the pranks seem less like an opportunity to release tension or play tit-for-tat with an annoying desk-mate, and more like an unhealthy obsession with making Dwight’s life miserable. This point is illustrated most clearly in the Season Two episode “Conflict Resolution,” in which Michael reads off all of the pranks that Jim has perpetrated on Dwight up to that point. These pranks range from relatively mild (paying everybody to call Dwight “Dwayne” for a day) to deeply disturbing (placing a bloody glove in Dwight’s desk and trying to convince him he had committed a murder). Jim will continue to play pranks on Dwight for the entire remainder of the series, even at times when they are supposed to be “friends” or on the same side. Nor does Jim limit himself to pranking Dwight–he pranks Andy too, and at one point pushes Michael into a Koi pond at a business meeting. In general, it seems as though anyone who rubs Jim the wrong way is at risk of becoming a target of his pranks.

It is important to note that provoking someone and then using their reaction against them is a common abuse tactic. There is even a type of abuser–the “Water Torturer”–who is defined by a tendency to do exactly this.

The Water Torturer genuinely believes that there is nothing wrong with his behavior. Since he subscribes to the idea that abuse has to include raised voices and physical assaults he thinks his actions are normal and acceptable.

When the Water Torturers [sic] friends, family, and even children see him remain calm while his partner is yelling or crying they come to believe his assertions that she is the problem and he is innocent.

28

Still, none of this is to suggest that Jim is a knowing abuser. He doesn’t mean to hurt anyone else, but he simply can’t help himself. For him, social cruelty is automatic, even unconscious. Once again, the clearest illustration of this occurs in “Conflict Resolution,” when, forced to confront the harm he has been causing Dwight, he says, “These actually don’t sound that funny one after another.” He then adds, hesitantly, as though he’s trying to convince himself: “But he does deserve them.”

Jim is also remarkably sexually frigid, especially in relation to the other men in The Office. Most of the male characters talk and think about sex quite frequently, whether or not they are actually getting any; but Jim is an exception. It is unclear whether he ever sleeps with Katy or Karen, and after he gets into a relationship with Pam Beesly–his alleged soulmate–he seems to sleep with her only out of duty. This sexual coldness does not go unnoticed by the other characters, as in the Season Seven episode “PDA,” Gabe Lewis says of Jim and Pam: “They don’t touch. They don’t kiss. You would hardly even know that they were husband and wife.” Nor does Jim seem to be holding back out of respect for women. In the episode “The Inner Circle,” when Will Ferrell’s DeAngelo Vickers invites several men–including Jim–to join his “inner circle,” Angela is the one who points out the apparent sexism of such an arrangement. Even when Jim goes to confront DeAngelo about it, he hesitates and falters in his speech, trying to stay on DeAngelo’s good side. In other words, Jim’s lack of sexual interest seems to stem not from a genuine desire for chastity and restraint, but from a coldness that permeates everything he does.

Nor is Pam much better. In her own way, she is just as manipulative and selfish as Jim. Not only is she his favorite audience in the pranks he pulls on his colleagues, but she is often his willing accomplice. Moreover, in the Season One episode “Basketball,” Pam, despairing over the possibility that Dwight will make her work on Saturday, muses: “Maybe I should sleep with him.” She walks her statement back the next instant, but the important point is that she knows how to use sex appeal to manipulate men.

Her selfishness and coldness become more apparent after she marries and has children. At this time, Pam has moved from being a receptionist to the sales department, where she has little success and makes little money. However, rather than quit her job and go home to raise her infant child, she reverse-engineers an entirely new position–that of Office Administrator–for herself, just so that she can continue to work and earn a generous salary. The fact that the company she’s working for is strapped for funds, and that her salary requests will potentially put more jobs at risk, makes this considerably worse. She initially claims that she has to work because she and Jim “need the money,” but that is unlikely considering they live in Scranton, which has a relatively low cost of living 29. Tellingly, after the birth of her second child, when Angela chides Jim for not making enough to allow Pam to stay home, Pam simply replies that she likes to work.

Pam also has a tendency to make Dwight do her jobs for her. After Dwight buys the office building that houses Dunder-Mifflin, he implements a number of cost-saving measures that severely reduce comfort and safety for everyone who works there. Pam attempts to confront Dwight about this, but nothing changes until Dwight takes pity on her and slips her the building codes, which he had been violating. A more damning example occurs at Gabe’s pizza party. Pam is unable to soothe her crying daughter, and so Dwight, who has a very soothing voice, picks her up and rocks her to sleep. In the end, Dwight is made to cradle the baby all night long–and cancel a rendezvous with Angela that both had been looking forward to all day.

Still, at least Jim and Pam show some ability to grow and learn from their mistakes. A much darker depiction of the “adjusted” manipulator can be seen in the form of Ryan Howard, a man who begins the series as a temporary worker and later becomes a permanent employee at Dunder-Mifflin at the behest of Michael. He’s about the same age as Jim (BJ Novak, the actor who plays him, attended high school with Jim’s actor John Krasinski 30), and, like Jim, initially seems like a beacon of sanity who takes the craziness of the office in stride. The fact that Michael harasses him constantly and treats him like his personal servant further lends him sympathy.

Things take a turn for the worse, however, when Ryan is fast-tracked to the role of Dunder-Mifflin’s vice president and relocates to New York City. Venkat Rao cites this event as the main evidence of Ryan’s “Sociopath” qualities 31. Once he has power, Ryan becomes arrogant and domineering, and ultimately commits fraud in order to boost sales numbers (for which he is arrested). Ryan also strikes up a toxic on-again, off-again relationship with Kelly Kapoor, a customer service representative who is just as shallow, selfish, and manipulative as he is. In the series finale, he abandons his baby in order to run away with Kelly for good! What all this suggests is that Ryan’s initial placid demeanor was just a ruse, and that his actions since obtaining power are a much closer approximation of what he is “really” like.

Although Ryan is one of the more openly villainous characters, there is some evidence that he, too, is a victim of circumstance. In 1980, when he was just one year old, Pennsylvania passed a law legalizing no-fault divorce 32. The very next year, David Elkind wrote a landmark book called The Hurried Child, which outlined all the ways in which adults were pressuring children to grow up too fast 33. Ryan also admits in his correspondence with Kelly that his childhood was not a happy one, and that he does not know what his future holds. In a poem he writes for her, he describes himself as “a child lost on a life raft.”

The “Thinking Man” in The Office

Of all the characters in The Office, the one who shows the clearest ability to think for himself is Dwight. Although he has difficulty fitting in and getting along with his coworkers, it’s pretty obvious that the reason for this has less to do with any social-skills deficit than with a desire to be his own person. The episode “Initiation” draws attention to this point deliberately; when Kelly complains about how weird Dwight is his girlfriend, Angela, replies: “He’s not weird. He’s just individualistic.” Although it might seem strange to describe someone as stupid as Dwight as a “thinking person,” Ayn Rand addresses this point as well in her essay. She says:

Intelligence is the ability to deal with a broad range of abstractions. Whatever a child’s natural endowment, the use of intelligence is an acquired skill [emphasis added].

34

What all this means for Dwight is that he knows how to think–he’s just not very good at it!

Dwight’s out-of-the-box thinking is most evident in his wacky antics and entrepreneurial projects, but it shows up in more subtle ways as well. For instance, in the episode “Grief Counseling,” when Michael asks his employees to share stories of loss from their lives, Dwight is the only one who has anything original to say. The rest of the speakers simply describe famous deaths from movies and try to pass them off as those of their own families. In a later season, when asked to describe his “perfect crime,” he proceeds to tell a ludicrously complex story about stealing a priceless chandelier and winning the heart of its owner. His distinctive thought patterns likely stem from his unconventional upbringing, as unlike most of the characters, he was raised on a farm in a large Pennsylvania Dutch family. Growing up, he would have had access to many more playmates and potential role models than his colleagues could command, which would have helped him explore his creativity and become more fully himself.

The clearest evidence that his status as a misfit derives from his free-thinking nature and not from any genuine lack of social skills comes from the way he behaves when he’s not working. Although at work he often seems like an irritable, impulsive stickler for the rules, at outside social functions he becomes sociable, suave, and laid-back. In the Season Two episode “Email Surveillance”, Dwight gets invited to Jim’s house party (which he mostly uses as an opportunity to make out with Angela), whereas Michael does not and has to crash the party later on. Later, in the Season Four episode “Night Out,” when Dwight and Michael accompany Ryan to a night club, Dwight ends up having to physically tear himself away from the local women, whereas Michael and Ryan fail to impress any of them. He also seems to get along with just about everyone he meets at Pam and Jim’s wedding in Season Six.

Dwight’s relationship with Angela is noteworthy as well. Angela, who works in accounting, is the office’s resident weird girl: she has trouble fitting in and uses her pet cats as an emotional crutch owing to a lack of close human relationships. Still, when she and Dwight are together they seem to be the happiest and most loving couple around. The reason for this is likely that Dwight sees in her the same kind of free-thinking misfit that he sees in himself. In The Organization Man, Whyte describes an editorial he wrote called “In Praise of Ornery Wives.” Whyte’s point was that, in the eyes of the modern organization, “the good wife is the wife who adjusts graciously to the system, curbs open intellectualism or the desire to be alone 35.” He had hoped that, by writing his editorial, he would make “ornery wives” who did not conform feel better about themselves. Angela often seems to be just the sort of “ornery wife” that Whyte was referring to, even though she technically does not marry Dwight until the series finale.

Another character who shows some ability to think for himself is, of course, Toby. Rao himself even notes this, as he labels Toby “intellectually a Sociopath, but without the energy or ambition to be an active Sociopath 36.” He further goes on to argue that Toby’s predicament stems from the latter’s awareness of the meaninglessness of his life, coupled with a desire to protect others from such awareness 37.

All in all, there are two moments in which Toby clearly demonstrates his ability to think and separate himself out from the pack. One is during the christening of Cece, Jim and Pam’s daughter. While the others gather in the main sanctuary for the christening, Toby wanders off by himself in order to ask God for help. What this suggests is that Toby has an awareness of religion that most of the other characters lack, and is aware that things could be different than they are. It also suggests that he has a liking for solitude–a trait completely at odds with the “adjusted” Organization Man’s temperament.

The second moment occurs in the Season Eight episode “The List,” when Robert California divides the staff into two seemingly arbitrary columns and invites those on the left hand side (including Toby) out to lunch. Robert California announces that he invited them out to lunch because they are “winners,” whereas those remaining behind are “losers.” Upon hearing this, Toby–and only Toby–stands up and walks out. Even Dwight, who is also present at the lunch, stays put due to his weakness for flattery.

In terms of formative experiences, Toby at one point reveals that he used to attend divinity school, but that he dropped out in order to be with the woman who would become his wife. Unfortunately, their relationship ended in divorce, and Toby now sees his daughter only sporadically. It’s telling that divorce is ubiquitous on The Office–just about every character seems to have been touched by it in some way, whether they are divorcees themselves or the children of divorce. Interestingly enough, the more divorces take place, the more likely it is that children will grow up to be like the characters on The Office. As Robertson points out:

[W]hen the parental role becomes weak and institutions and peer groups take over family functions, love becomes separated from discipline and the child’s conscience becomes “outer-directed” toward whatever is necessary to fit in with the surrounding environment. Right and wrong are replaced with fashionable and unfashionable. But there was also a darker side: those who found fitting in difficult or impossible had no capacity to find strength and reassurance from an internal code of conduct and thus became alienated.

38

It is telling that most of the actual children and young people introduced in The Office seem to be just as socially-awkward and miserable as their parents.

How The British Office Fits In

Of course, no discussion of The Office would be complete without taking into account the British version that started it all. Although Rao did not create the Gervais Principle with the British Office in mind, some of the points he makes apply to the British show as well. Furthermore, the British series hints at much the same societal malaise as the version from the US, albeit in a more subtle and understated way.

Many of the same themes of conformity and leveling that Rand and Mack complain about were described decades earlier by C.S. Lewis, in his satirical essay Screwtape Proposes a Toast. Lewis, writing towards the end of the 1950’s, argued that the United Kingdom was fast becoming a society in which

those who are in any or every way inferior can labor more wholeheartedly and successfully than ever before to pull down everyone else to their own level. But that is not all. Under the same influence, those who come, or could come, nearer to a full humanity, actually draw back from it for fear of being undemocratic. […] To accept might make them Different, might offend against the Way of Life, take them out of Togetherness, impair their Integration with the Group. They might (horror of horrors!) become individuals.

39

In his book The Abolition of Britain, which was written towards the end of the 1990’s, journalist Peter Hitchens attempted to map the cultural decay of Britain in the Twentieth Century. Unlike Lewis, Hitchens posits that the decline first began in earnest after the death and funeral of Winston Churchill in 1965, when Ricky Gervais would have been about four years old 40(his costars, Martin Freeman and Mackenzie Crook, would not be born for another several years 41 42). Since then, the United Kingdom has experienced many of the same culture shocks as the United States, including the sexual revolution, the rise of the television, the breakdown of the family, and globalization 43. At his most frustrated, Hitchens makes the following observation:

Society has been reconstructed so that the most abject conformism appears to be rebellious, casually clothed, loud-mouthed, safely undisciplined, speaking in the glottal accents of Estuary English. Real individualism, […] on the other hand, is merely eccentric, barmy, bonkers, contemptible.

44

Interestingly enough, although David Brent is a smarmy, compulsive people-pleaser in much the same vein as Michael Scott, there are no truly “adjusted” characters in the main cast of the British Office. The best example of such a person is Neil Godwin, a man who becomes David’s boss in the second series. Like Jim, Neil is suave and effortlessly cool, but he also appears to be, in Robertson’s words, a “well-adjusted, achievement-oriented [adult] who [lacks] any solid inner core of conscience 45.” Neil’s good friend Chris Finch, the traveling salesman, may also count. Because he is a manipulative bully who enjoys dominating others, he has more in common with the cast of the US Office than with his own castmates. It is interesting to note, however, that Chris Finch is one of the few characters in the series who does not speak “Estuary English,” since he is from Yorkshire.

By contrast, neither of the British salesmen, Tim Canterbury and Gareth Keenan, seems to be exactly “adjusted.” Both of them have moments of manipulation and going along to get along, but they also both demonstrate some creativity and clear-headedness, and neither is entirely beholden to peer pressure or the court of public opinion–Rand’s “will of the pack.” All the same, Gareth–who inspired Dwight–seems to be the more independent-minded of the two. This is evidenced most clearly in the fourth episode of the first series, in which a visiting presenter gives the staff of Wernham-Hogg a riddle to solve about a farmer ferrying cargo across a river. Gareth insists on asking questions about it and contrasting it with his own knowledge and experience, whereas Tim simply accepts it at face value. Gareth is also fascinated by death, a trait that some researchers connect with feelings of “existential isolation,” or an inability to fit in with others 46.

Both salesmen also seem to have had unhappy childhoods, and possibly even a Comprachicos-style upbringing. Tim still lives with his parents at age thirty, and it is not at all clear that their relationship is emotionally close. As Nancy Verrier points out in her landmark book The Primal Wound, “Before one can truly separate, one must first connect 47.” Likewise, in a scene in Series Two, Gareth relates a story about how he used to play the card game Top Trumps by himself, presumably because no friends or family were around to play with him.

The Office is a profound and provocative series for many reasons. The most impressive thing about it, however, is the way in which it uses its characters to call attention to the ills that are afflicting society as a whole. It’s safe to assume that without the widespread problems of divorce, checked-out parenting, and social conformity plaguing the cultures of both the United States and the United Kingdom, the business world would be much less corrupt. On the other hand, were that to happen, the characters of The Office wouldn’t be so popular and relatable. For better or for worse, as long as these problems persist, the workspaces of the world will be populated by people who look and act like the show’s cast members for a very long time to come.

Works Cited

- Rao, Venkatesh. “The Gervais Principle, or The Office According To ‘The Office.'” Ribbon Farm, WordPress 7 October 2009. https://www.ribbonfarm.com/2009/10/07/the-gervais-principle-or-the-office-according-to-the-office/ ↩

- Rao, Venkatesh. “The Gervais Principle VI: Children of an Absent God.” Ribbon Farm, WordPress 16 May 2013. https://www.ribbonfarm.com/2013/05/16/the-gervais-principle-vi-children-of-an-absent-god/ ↩

- Rao, 2009 ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Rao, Venkatesh. “Books.” Ribbon Farm, WordPress. https://www.ribbonfarm.com/books ↩

- “Rainn Wilson: Why the Awkward Humor on ‘The Office’ Is Funny | Big Think.” YouTube, uploaded by Big Think, 20 May 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aIiErKX6JDY ↩

- Herman, Allison. “The Rise and Fall of the Mockumentary Sitcom. The Ringer, Spotify AB, 30 April 2020. https://www.theringer.com/tv/2020/4/30/21241996/mockumentary-sitcoms-the-office-parks-rec-reality-tv ↩

- Smith, Neil. “The Office: 10 David Brents from Around the World.” BBC News, BBC, 20 February 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-43113390 ↩

- Jeffery, Philip. “The Bad Old Days: How Scientism and Market Logic Corroded the Family Long Before the Sexual Revolution.” The Public Discourse, 9 December 2021. https://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2021/12/79405/ ↩

- Whyte, William. The Organization Man. Simon and Schuster, Inc. 1956 ↩

- Whyte, 1956, pp. 262 ↩

- Rand, Ayn. “The Comprachicos.” The New Left: The Anti-Industrial Revolution. 1971. https://stephenhicks.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/RandAyn-The-Comprachicos.pdf ↩

- Rand, 1971 ↩

- ibid. ↩

- Mack, Dana. “Schooling for Leveling.” The Assault on Parenthood. Simon & Schuster, 1997, pp. 129 ↩

- Hymowitz, Kay S. “Fear and Loathing at the Day-Care Center.” City Journal, 2001. https://www.city-journal.org/html/fear-and-loathing-day-care-center-12174.html ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Lewis, Clive Staples. “The Cardinal Virtues.” Mere Christianity, CS Lewis Pte. Ltd., 1952 ↩

- Tribble, Jesse. “The Office – I. Hate. People.” YouTube, uploaded by Jesse Tribble, 5 July 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wwHdKDpBYXM ↩

- Rao, Venkatesh. “The Gervais Principle III: The Curse of Development.” Ribbon Farm, WordPress 14 April 2010. https://www.ribbonfarm.com/2010/04/14/the-gervais-principle-iii-the-curse-of-development/ ↩

- “Why Jim Halpert is a D*ck | Cinema in Thought.” YouTube, uploaded by YourEverydayTheorist, 1 May 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0R4YUD-IQV8 ↩

- Brown, Jena. “The real hero of ‘The Office’ was Dwight. Jim was just a bully who never grew up.” Insider, 3 February 2021. https://www.insider.com/dwight-was-the-best-on-the-office-and-jim-sucked-opinion ↩

- Wiseman, Rosalind. “Friendly Fire.” Masterminds & Wingmen. Harmony Books, 2013, pp. 213 ↩

- Rand, 1971 ↩

- Rand, 1971 ↩

- Rand, 1971 ↩

- Robertson, Brian C. “The Family Under Siege.” Day Care Deception, Encounter Books, 2003, pp. 145 ↩

- Smith, Emily. “Profile of an Abuser- Water Torturer.” Muchness Mama, Sassy Suite LLC 27 March 2019. https://www.muchnessmama.com/profile-of-an-abuser-water-torturer/ ↩

- Sperling’s Best Places. “Cost of Living in Scranton, Pennsylvania.” Sperling’s Best Places. https://www.bestplaces.net/cost_of_living/city/pennsylvania/scranton ↩

- Viser, Matt. “Double scoops: At Newton South, two papers vie to make headlines.” The Boston Globe, 20 February 2005. http://archive.boston.com/news/local/articles/2005/02/20/double_scoops/ ↩

- Rao, 2009 ↩

- Gold-Blinken, Lynne Z. & Jack A. Rounick. The New Pennsylvania Divorce Code, Villanova Law Review, 25(4), 1980. https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=2280&context=vlr ↩

- Elkind, David. The Hurried Child: Growing Up Too Fast Too Soon. Hachette Books, 1981 ↩

- Rand, 1971 ↩

- Whyte, 1956, pp. 276 ↩

- Rao, 2009 ↩

- Rao, 2013 ↩

- Robertson, 2003, pp. 146 ↩

- Lewis, Clive Staples. “Screwtape Proposes a Toast.” Saturday Evening Post, 1959, pp. 88 ↩

- “Ricky Gervais.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 April 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ricky_Gervais ↩

- “Freeman, Martin (1971-).” BFI Screenonline, 2014. http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/541286/index.html ↩

- “Mackenzie Crook.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 22 March 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mackenzie_Crook ↩

- Hitchens, Peter. The Abolition of Britain, Encounter Books, 2000 ↩

- Hitchens, 2000, pp. 297 ↩

- Robertson, 2003, pp. 147 ↩

- Pappas, Stephanie. “Why Some People Have Endless Thoughts Of Death. They May Be ‘Existentially Isolated.'” LiveScience, 16 September 2019. https://www.livescience.com/existential-isolation-endless-thoughts-of-death.html ↩

- Verrier, Nancy Newton. “Issues of Guilt and Shame, Power and Control, Identity.” The Primal Wound, Gateway Press, 1993, pp. 99 ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Interesting article!

Great to see this in the lineup. I appreciated the inclusion of the British version as well.

Wonderful review of the legendary series “The Office”

First time I saw The Office, I was busy re-stringing my guitar and not really paying attention to what I genuinely thought was a documentary playing in the background. Then I caught a few lines of David Brent, and I thought – wow, what an a-hole – yet familiar to a few bosses I’d known before. Was wondering why they were giving him airtime.

A few minutes later, I was glued thinking “wait, what – this can’t be real?”. By the end of the show I was in hysterics knowing that this was ground breaking stuff and could not wait for next episode.

I miss those days before social media when you could just come across something without having heard anything about it. Like you I remember watching the first episode or two and not knowing whether it was real or not. Nowadays it would be previewed, reviewed, analysed and discussed to death as soon as it’s aired.

Loved the office. It came out just as i was entering ‘the real world’ and getting a job after uni. After years of studentdom i found myself in offices with shirt and tie and banality and middle aged people. Some jobs were a great laugh to be fair, but the working environment was still dull.

Amazing Deb. Both brilliant analysis and insightful social commentary – definitely worth the read.

Great deconstruction of The Office.

This appears to border on cynical thoughts, but the principle makes sense.

The first — and only — rule of the Gervais Principle is: you do not talk about the Gervais Principle.

UK office! Utterly brilliant from start to finish. My partner kept on at me to watch US Office. I thought, nah, it’ll be rubbish, watched the first few episodes under duress … still rubbish … watch ed a few more and by jingo if I didn’t end up enjoying the US one even more. It wasn’t groundbreaking, the UK Office had done that, but it was brilliant, too.

I’ve always liked the US version of the office. Not as much as the original but it’s definitely been worth my time.

I’ve never found the supposed humour of The Office the slightest bit funny, it has spawned a whole genre of unfunny comedies that really rely on cruelty to dumb humans for laughs , it’s crass and cheap laughs really were a step down in quality.

Totally agree!

Rather than admit that it was a ‘let’s laugh at the geek’ show, it’s defenders point to irony. I have found a number of people who are Gervais fans are also those that suggest that Clarkson is just ‘controversial’ rather than offensive.

However, I would recommend the gentle and well observed comedy of the Detectorists, written by Makenzie Crook, as a series that celebrated the diversity of the characters we have around us.

I am a huge Gervais fan and I have always hated Jeremy Clarkson. I think your radar is a tad off.

The office is satire, one of the most difficult forms of comedy to get right. It was art imitating life (and doing a very good job of it), so yeah it’s always going to be cruel to some degree as life is.

To each their own, but for me the characters punching down for constant laughs were always meant to be seen as ludicrous, and doing it because they were insecure (in themselves, or about the situation they were in). I certainly read it that ‘laughing at the geek’ was nothing to be admired – those that did it incessantly and without remorse (eventually) got their comeuppance, and Brent’s last lines to Finchy showed that even he was on a path to redemption after all those years of making himself feel good at the expense of others. Just my two-pence!

What was disturbingly funny for me was that it was so true to life, as outlined in this article very well.

The observations were really spot on. I used to think Brent was massively exagerrated because there was no way someone could act the way he did without getting a serious disciplinary or the like, but having worked in my current office job for eight years, it’s massively on point, partly because of just… the malaise of office work. Yes, your boss is an arse, but what’s easier – grinning and bearing it or stirring up a hornet’s nest and making your day more difficult?

Thing is, this actually makes the British Office more optimistic than it’s often given credit for (and perhaps than it would be in real life), since at the end of the series David is fired for incompetence and replaced with someone better. Later adaptations of The Office, including the US one, are a lot more cynical in that the boss gets away with so much more and never really faces any lasting consequences. For this very reason I always get a bit annoyed when people act like the US Office is “lighter and softer” than the British one, because to me the opposite is closer to the truth.

Oh yeah. I’ve worked in several positions where there was at least one David Brent somewhere in management. And some Gareth’s beneath them. And many of the plots and subplots of this show occurred in my experience in office environments also, such as a strange plutonic connection between the receptionist and one of my colleagues but her having some macho boyfriend.

I was living in the UK when this aired. I had never seen anything that made me roar with laughter as much. It was the funniest show of all time bar none.

I think it’s fair to say that The Office’s humour divides people into two camps: (1) those, with a nuanced sense of humour, who can appreciate the subtly funny, and often tragic, side of life, and (2) t**ts.

You forgot (3) Those who think that because they like it but others dont then they must be from a higher intellectual plain.

The mockumentary aspect always seemed to me the least interesting element of The Office, and focussing on it so much risks obscuring what really makes it great, which is that it slots so wonderfully into the greatest traditions of British comedy. Brent is an updated Tony Hancock and Tim’s glances to camera go all the way back to Stan Laurel. Gareth could have slotted easily into any number of sitcoms from Steptoe to Porridge. The common thread of all of these is that they’re popular, music hall-derived characters and shows – perhaps Gervais’s biggest achievement is swerving the endless Oxbridgeness of BBC comedy, both in influence and result. It’s working class comedy without being stereotypically working class – after all, the 90s were when kids from w/c families first tended to end up in provincial offices, rather than industry (which no longer existed).

I’ve been wondering about the class dimensions of the series for awhile now, because although it’s set in a white-collar office there are a few characters who seem to be working-class in origin. Gareth in particular strikes me as someone from a working-class background who is desperately trying to prove that he belongs in a middle-class (or higher) job. It’s even sort of implied that one of the factors contributing to Tim’s dislike of Gareth is that the latter is lower-class than he is, although this clearly isn’t the only or even the main reason he dislikes him.

This article and this comment thread is really interesting, thank you.

Do you think Brent himself is a middle class person trying to adopt working class mannerisms to be cool and fit in?

Actually, Brent is an updated version of Oliver Hardy. Look at the way he fiddles with his tie. It’s an acknowledged homage.

It’s an interesting question. David certainly does have some middle-class affectations, most notably his interest in political correctness (my understanding is that most working-class people don’t view political correctness as worth getting good at, and the working-class characters in The Office bear this out). He also drinks lager when he goes to bars, rather than more traditionally “English” drinks like ale or apple cider. Additionally, since he and Tim are so similar in so many ways, it’s possible that he is meant to be of the same class as Tim is, and Tim seems pretty soundly of the middle class (we see him make a disparaging comment about the working-class warehouse staff in one episode, and in another he mentions going on safari, which most working-class people probably couldn’t afford). On the other hand, David also talks with a more lower-class-sounding accent than Tim and some of the other characters, which I assume is real. He’s also bad at political correctness and cultural competency, which suggests he hasn’t had the time or inclination to get good at it. I’m guessing lower middle class is the best way to describe David’s background, but it’s hard to judge because we know so little of his past.

It almost certainly is the case, though, that David is higher on the economic ladder than either Gareth or the actual warehouse staff, by birth as well as in terms of his salary.

I hadn’t thought of the 90’s working experience for young people like this but it’s so true. I was part of it, the desire to work in an office to feel more upwardly socially mobile. The funny thing about it, which Gervais taps into perfectly, is that it takes no more skill or common sense, and sometimes a lot less, to undertake the banal work in an office than it does to do lower paid and socially perceived lower class work in a factory or trade. Yet learning a trade, for example, and making a business or career out of it can take a lot of skill, knowledge, perseverance and hard work, amongst many other skills and work ethics.

This has really made me think a lot more on the subject than i ever did; thanks!

Right, and the biggest example of this is David Brent himself. This is part of the point of the Gervais Principle (and related concepts): that one can get promoted to a managerial post without being especially intelligent or competent.

This is a genuinely illuminating comment – thanks!

Great analysis.

And the early 90s was also a time when New Labour was trying to pretend the working class no longer existed.

Even though I left the TA over 25 years ago when we married. My daughter, 17, calls me “Gareth” when she wants to wind me up.

An enduring comedy that still hits the mark on office life perfectly.

I always remember at the time of The Office episode when Brent was telling his team there would be job losses but he would be promoted, we lived a similar experience. Our department manager came with a HR rep on a Friday afternoon, that was also my team leader’s birthday, to tell us the funding for our project, and ergo our jobs, had finished.

The meeting ended with the department manager telling us about her new job and her, and the HR rep sitting there eating pieces of my team leader’s birthday cake.

The US version is much funnier.

It really is. I was hugely sceptical starting out watching the US office and only got round to it this year. I never believed Americans could do the office better than Gervais and Merchant. The UK office is one of my favourite shows ever.

It took until a handful of episodes into the US office for me to really get into it, but after that I was utterly hooked. It’s trump card is that in having 9 seasons it was able to develop real character depth and storylines that you completely buy into and the ugly flaws on one hand set against the real depth of empathy and strength of the characters is beautifully played out.

It’s one of the highest rated TV shows ever made and as a comedy, gad me in tears a few times not for being funny, but for dealing with real life stuff so touchingly and realistically.

It’s a brilliant, brilliant piece of TV.

It’s the UK The Office pushed through the blender of the traditional ensemble US sitcom format. Which is fine, I thoroughly enjoyed watching the whole thing in lockdown 1.

But it only really works if there’s a straight person amongst the “insanity” of all the comic characters (Jim and Pam became as oddball as the rest by about half way). Things picked up when Idris Elba entered as a straight manager sent from head office, but that only lasted for two or three episodes.

The UK Office didn’t have that issue because the characters are subtler, much more like the people you’d see on the British “fly on the wall” TV documentaries that were its inspiration (i.e. normal people). US sitcoms don’t really do “normal people”.

Lots of people think Parks & Recreation gets better after season 1. It suffers from the same problem as the US Office IMO. Too much craziness without a straight character to “centre” it all (the role fulfilled by Mark Brendanawicz in season 1).

Ultimately it’s a question of differing tastes between UK and US audiences, but there’s no way the US Office is better than the original, unless better simply means less subtle, more removed from reality.

I agree with what you’re saying and would take things a step further in that, IMO, the “character development” that garners the US Office so much praise is a bit of a double-edged sword. For one thing, as I said in my article, the characters are nearly all terrible people, which makes it harder for me to care about them no matter how much they “develop.” For another, as I watched the series I noticed numerous examples of what can only be called unforced errors in the way the show fleshes out the characters’ lives and worlds. For instance, was it really necessary to make Dwight’s family members literal Nazis?

I saw the US Office before the British one, and at the time I really liked it. It’s really funny, the satire is beautifully-written and a lot of it is still relevant to this day. But the more time I spend with other versions of The Office (including but not limited to the original British version), the less it appeals to me.

It is good, I’ll give you that. But aside from the first 1-2 episodes they can no longer be compared – apples to oranges.

The U S Office is the UK Office diluted of all subtlety and humour. Not funny at all.

American and British people also have extremely different senses of humor, that could be it.

Off the top of my head I can’t think of any American adaptations of UK comedy shows that I could bear watching. The UK version is always better.

Contains tons of genius insight into The Office. Shared with my work buddies.

Traumatizing, the red pill for anybody that works in a company.

One of the all-time great sitcoms. It’s just a shame that post-Extras Gervais completely lost it – hard to believe that Derek, After Life etc were written by the same person.

I haven’t seen Afterlife but Life’s Too Short was pretty poor, and Derek was terrible. Even his stand-up went downhill after a good start.

I think he relies too much on the ‘questioning things while being a bit of an wanker and driving a skit into the ground’ routine in his standup now; I think it was Humanity where he opens with a bit about getting called transphobic and being accused of deadnaming Caitlyn Jenner while presenting the Golden Globes, and it shifts into a routine about Bruce Jenner visiting his doctor and it was just… So strained and awkward and actually coming across as massively transphobic, when he was trying to make the case that he wasn’t and that Jenner’s gender and status shouldn’t make them above being called out for crimes and the like.

It was just ugly and self-indulgent and dragged out. Not nearly as funny as his earlier shows where he invokes Karl and the like while talking about Noah and so on.

After life is exceptional. And I’m not just trying to argue – it’s some of his best work. Personally I loved Derek (it made me cry quite a few times), but I appreciate that it’s a bit harder to get in to than some of his other shows.

After life is good, rather than great, because he has to inject his little bits of spite here and there which are unnecessary and show how ‘daring’ he is by targeting e.g the kid.

It was totally unnecessary and was targeting laughs, un-ironically, from the gutter. Take that scene out or change it (punch up) and the show isn’t diminished.

I’ve never felt as happy about not working in a large organization as when i finished reading this.

Good psychoanalysis of the Office.

The Office is still genius. I’ve re-watched it quite a few times, and it still stands up. The American version was a rare example of a US remake actually being quite good, though for me it’s mildly amusing and watchable, rather than hilarious and must-see like the original. Extras was great too.

Never have I pondered the relatability of The Office in all facets of life. When I watched it the first time, I was more interested in the budding romance of Jim and Pam! After reading this article however, I will be re-watching the Office through a much larger lens. What struck me the most was talk near the beginning about the conformity and “go with the masses” attitude that is pushed on, well, all of society. While being something I had not really considered much before, I, sadly, cannot disagree. Overall, a really well-written and thought-provoking article!

This article, and the Gervais Principle blog posts should be required reading for anyone starting at a large company.

Great stuff. If you enjoyed Dilbert or The Office but not sure why they are so funny. Now you know. 🙂

As a person with a sociology background, I think this article has some interesting contextualization, such as that of the Organization Man, industrialization, and discussions on institutions shaping children into conformists. I also agree with your points about Jim displaying negative qualities. However, the note about Jim being sexually frigid stood out to me as neglecting some examples for the character. He’s shown to be sexually warm with Pam. Remember that after he professes his love to her, he goes up to her and kisses her (Casino Night episode). In the episode “Job Fair,” Jim closes a large account after a golf game, Pam kisses him in front of Michael, Dwight and Andy. At first, they restrain themselves in an attempt to be professional, but Jim quickly decides to dismiss that, and be proceeds to tenderly kiss her in front of the others. Recall in the season 4 episode “Money,” Jim comforts Dwight by extending how he felt when Pam was with Roy. He reveals what we already know, that he’s in love with her. He leaves the stairwell and goes to kiss her while she’s at her reception desk. Additionally, Pam and Jim have sex in the warehouse (PDA episode, season 7). During the interview where they act as if they wouldn’t have sex in the office, Jim casually mentions that they have a shower at home, implying that they also have sex there. Overall, I do not see that describing Jim as sexually frigid is necessarily representative of him, he’s quite focused on Pam, and he’s displayed his love for her physically in the workplace throughout the series.

Your critique of the comment about Jim’s sexuality leads to wonder what you think about MIchael. I would say that at times he felts performative in his sexuality and that he tried to hard to be macho and a ladies’ man.

Michael’s behavior is definitely performative–he’s very much aware of the camera and goes to great lengths to get and keep the attention of both his staff and the camera crew. Interestingly enough, having dug into the mythology of The Office for a few months now, I actually think Michael has a lot more in common with Bernd Stromberg (the boss from the German Office adaptation) than with David Brent from the original British version. Bernd is far more likely than David to act the part of a ladies’ man, among other things.

I’ve been aware of this for a long time as I do work in a Big Corp but I’ve never seen it written down. Amazing.

I tried to like The Office but there’s something about Ricky Gervais that I just can’t abide – the same goes for Michael McIntyre. Both appear to be wildly successful so I’m content to be in a minority.

There’s many things about Gervais I can’t abide: his stand-up, his one-note persona, his ‘everyman’ ego, his cod atheism, his thinking he single-handedly invented the podcast, his glee at punching down, pretty much his entire work in film.

The Office, however, is a masterwork of his that I can only admire. Almost like it was conceived and executed by an entirely different person.

The real genius is how close to the bone it is to real life.

I have been managed by several Brents, suffered several Gareths, and shared a beer with many a Tim, trying to make sense of it all. And everyone knows a Finchy, unfortunately.

It’s just perfectly observed, perfectly written and perfectly played. Nothing more to say.

The organisation I work seems to delight in promoting the Brents to senior management. However, they are Brents without the human touch. Even more dangerous.

Which is precisely why I don’t want to watch that when I get home from work, having spent the whole day trying my best to resist rearranging the culprits’ faces with a fire extinguisher. Genius? Nope.

It is a fascinating examination of organizational structures using the television series The Office as a case study. Fantastic analysis and interesting stuff.

Good writeup on the social dynamics of a workplace through the lens of The Office.

The Office makes me cringe so hard I find it a really tough rewatch but I still think it’s brilliant.

Ricky’s comedy even today brings light to issues in Western society, I still think it could be made today.

My favourite line from the office is when Gareth says “It’s before racism was bad” when he’s talking about the Dambusters.

The layers of comedy run deep, truly why it’s a classic.

I just couldn’t watch the office. To me it really was the real thing, with unprofessional bosses, vulnerable victims of mild bullying and ridicule, and that’s without my own sense of imposter syndrome placing myself in Brents shoes… which as an employee I fortunately (perhaps) have never been.

So cringeworthy, I just couldn’t .. sorry.

It’s okay. Your loss.

I know other people who can’t watch any kind of ’embarrassment’ comedy. Empathy at its most empathetic…

I have trouble with a lot of “embarrassment comedy” – I can’t watch any of Sacha Baron Cohen’s stuff – but didn’t have that problem with The Office. I think it’s because The Office has a very human undercurrent that it never loses. It’s not based purely on cynicism and contempt, as some imitations could be. It’s a difficult spot to hit, and managing to hit it is one reason The Office is good.

(A similar thing happened with Viz and its many later imitators in the late 1980s / early ’90s. Most of them were terrible, but Viz always seemed to stay just on the right side of some line of sympathy for its characters and targets, even the awful ones.)

I think embarrassment humour only works if the characters are clearly defined.

I remember watching the first episode of The Office with my dad. He spent the full half hour trying to work out if it was real or not, despite me telling him it was acted and not set in an actual paper merchants. I think it took him until the second series to finally get it was a mock, not a documentary, and he finally said, “it’s funnier than I thought, this”.

I have zero experience from the corporate world and haven’t seen a single episode of the US or british Office. But loved reading this.

In 2002 I came home from my miserable job, sat on the sofa, and drank a bottle of cheap red wine by myself while watching every episode of The Office back to back.

It inspired me. The next day I gleefully resigned.

Good for you and I hope you didn’t look back.

Don’t forget Stephen Merchant’s dad as the guy stumbling into shot and just staring at the camera.

I didn’t.

I went on holiday, then spent the rest of the summer watching Euro 2002 and playing pitch and putt, then I did some temping jobs. I finally got a proper job again 18 months later.

It was a brilliant year. If I ever meet Ricky Gervais I’ll thank him for it.

Some years ago I had a good job in West London (in the sense that the work was mostly interesting) but some of the people were horrible. I did not get on with my team leader. She had (politely) berated me for not completing a project in good time. This was because she assigned me a case which legally indefensible. Me and a planner spent best part of a wasted week trying to defend the indefensible. My employer was very very lucky to avoid a costs order. In my experience if one had been granted it would have been in the region of about £100,000.

That is why I was behind. I saw her have a quiet word in the ear of the head of department and they went to a side office.

I picked up the files from my desk and put them back into the file storage room. Then cleared out the papers from my own locker and put them.im the recycling bin.. Then I went to the team leader’s desk. Placed my ID card from my neck and company phone on it and quietly left the building.

I went to the pub.

The supporting cast for The Office is superb. Matthew Holt, as the IT tech, and Elizabeth Berrington, as Tim’s pregnant colleague, are brilliant.

I’ve come across plenty of Chris Finch’s in my time unfortunately..

Yes me too and they were in sales. Loved the office and fancied Tim for his deadpan put downs.

You note that there are many adaptations including Israel and India and reference a link (8th). It might be important to remark that the Indian remake is in the making, and currently there is in fact no Asian remake of the show.

Definetly a generational gap in how people view The Office. A very relatable show.

Never watched much of The Office, but can definitely see how it plays with the Gervais Principle.

My parents are much older than me and enjoy watching The Office, although I did have to be the one to get them into it. I’m curious why they resisted watching it at its original air date — maybe seemed like a repetition of the stuff they had dealt with during the day at work? Interesting, that yes, the majority of the online fanbase is young people who’ve never even worked in an office.

The office for me was only something to be absorbed through cultural osmosis. Nothing about the character compelled me to watch and honestly I still wonder why the show has persisted as long and as strongly as it has. This is a very detailed piece about one of the biggest TV shows in recent decades but my biggest and most burning question is still “why”.

Wow, great background & breakdown of the origins and influences. It’s really interesting to me how the show is received differently among different age groups. While this is unsurprising when put into context, I wonder how future generations might vary in perception from the current younger viewership.