The Origins of Middle-Earth: Gods, Poems, and Dragons

In addition to being the popular and celebrated creator of Middle-Earth, J. R. R. Tolkien was a renowned scholar in Anglo-Saxon languages and literature. His essay entitled “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” is considered the turning point in interpretation of the poem Beowulf, and his own translation of the ancient poem was just recently posthumously published. As for Tolkien’s legendarium surrounding The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, it has been interpreted in many ways. Some have argued that the War of the Ring is an allegory for the Second World War, while others maintain that Frodo’s bearing of the One Ring is a symbol for the Christian’s battle against the temptation of sin and power. While those would be terrific articles to write, the purpose of this essay is not to pick sides of interpretation, but rather to uncover the Norse and Anglo-Saxon literature – in which Tolkien was so well-versed – and synthesize its impact on Tolkien’s Middle-Earth. Literature such as that of Tolkien is much more understandable – and enjoyable – when its origins can be identified and analyzed.

Of Gods and Dwarves

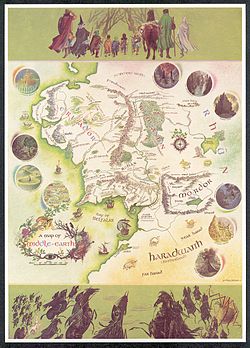

The origins of Middle-Earth and many of Tolkien’s characters can be found in Norse mythology, specifically The Elder Eddas written by Saemund Sigfusson. The name of Middle-Earth is derived from Midgard, the Norse name given to the whole of the man-inhabited world. According to The Elder Eddas, Midgard was created by Odin. However, he is not named at first as Odin but rather, in the first sentence of the edda, as Valfather, or “All-Father” (Sigfusson 1). Similarly, in Tolkien’s The Silmarillion, the first sentence introduces Eru, “who in the Elvish tongue is named Ilúvatar” (25). In the index of the book, Ilúvatar is listed as meaning “Father of All” (336). Additionally, any fan of The Hobbit or the Dwarves of Middle-Earth in general will find that in the first section of The Elder Edda concerning the creation of the world, there can be found many familiar names. “Then was Môtsognir created greatest of all the dwarfs, and Durin second; there in man’s likeness they created many dwarfs… Nâin, Dain, Bömbur, Nori… Thrain, Thekk, and Thorin, Thrôr… Fili, Kili, Fundin…” (Sigfusson 2).

Thorin is the name to attract attention, as he is known by Tolkienites as the Dwarf who dared to reclaim the Lonely Mountain from the dominion of the dragon Smaug. Thorin, then, is rightly named; in the index of the Saemund’s edda, Thorin’s name is derived from the Norse noun thor meaning “audacity,” and the verb thora “to dare” (Sigfusson 344). Additionally, in The Hobbit Thorin describes the coming of his grandfather Thror to the Lonely Mountain, saying he and his people “made huger halls and greater workshops… [and] grew immensely rich and famous… Altogether those were good days for us, and the poorest of us had money to spend and to lend” (Tolkien, Hobbit 23). Thror, being King under the Mountain and the progenitor of Erebor’s greatness, also has a significant name that comes from the Norse verb throa “to increase, to amplify” (Sigfusson 344). Tolkien was no doubt well-versed in the mythology the Anglo-Saxons borrowed from their Nordic forefathers.

Kings and Golden Halls

To keep Norse mythology from overrunning this article, the gears ought to be shifted to Beowulf, the ancient poem concerning an aging Danish king who is aided against the monstrous intruder Grendel by a noble Geatish warrior and his companions. The story of Beowulf is comparable to the subplot of The Two Towers in which Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli help King Théoden in his own war against Saruman. Firstly, the similarities between Aragorn and Beowulf should be outlined. Both are of noble birth and possess great strength. When Beowulf arrives with his band on King Hrothgar’s shores, his first lines of dialogue are, We belong by birth to the Geat people and owe allegiance to Lord Hygelac. In his day, my father was a famous man, a noble warrior-lord named Ecgtheow. He outlasted many a long winter and went on his way. All over the world men wise in counsel continue to remember him… So tell us if what we have heard is true about this threat, whatever it is, this danger abroad in the dark nights… I come to proffer my wholehearted help and counsel (Beowulf 47). Here, Beowulf is more or less giving his credentials to Hrothgar’s lookout as to why he should be permitted to go to Heorot where Hrothgar rules.

In The Two Towers, Aragorn, unlike Beowulf, is welcomed into the kingdom of Rohan with much more skepticism by Éomer, King Théoden’s nephew, who asks, “At whose command do you [Aragorn] hunt Orcs in our land?”. Aragorn responds by crying, “I am Aragorn son of Arathorn, and am called Elessar, the Elfstone, Dúnadan, the heir of Isildur Elendil’s son of Gondor” (Tolkien, Lord 433). Both of our heroes gain access to the kings in each story by telling of their noble birth. Aragorn being a Dúnadan is important because the Dúnedain, in Tolkien’s fiction, are the descendants of the lost kingdom of Men called Númenor. According to Tolkien, they were “far fewer in number than the lesser men among whom they dwelt and whom they ruled, being lords of long life and great power and wisdom” (Tolkien, Lord 1129). Éomer himself shows admiration for Aragorn’s speedy arrival in Rohan: “Forty leagues and five you have measured ere the fourth day is ended! Hardy is the race of Elendil!” (436). So also must Beowulf be equally superhuman if he can rip Grendel’s arm from its socket with his bare hands (58) and afterward live as king of the Geats for half a century (89), which is an unusually long reign even by today’s standards.

Also worthy of note are the similarities between Hrothgar’s court at Heorot and Théoden’s at Meduseld. In Beowulf, Heorot was established by Hrothgar himself, “a great mead-hall meant to be a wonder of the world forever… The hall towered, its gables wide and high and awaiting” (43). Later, as Beowulf and his men approach Heorot, “the timbered hall rose before them, radiant with gold. Nobody on earth knew of another building like it. Majesty lodged there, its light shone over many lands” (48). Strikingly similar is Legolas’ description of Meduseld as he, Gandalf, Aragorn, and Gimli approach it, describing the houses of Edoras and “in the midst, set upon a green terrace, there stands aloft a great hall of Men. And it seems to my eyes that it is thatched with gold. The light of it shines far over the land” (507). The line concerning “light” was almost certainly borrowed directly from the description of Heorot.

Where is the Horse and the Rider?

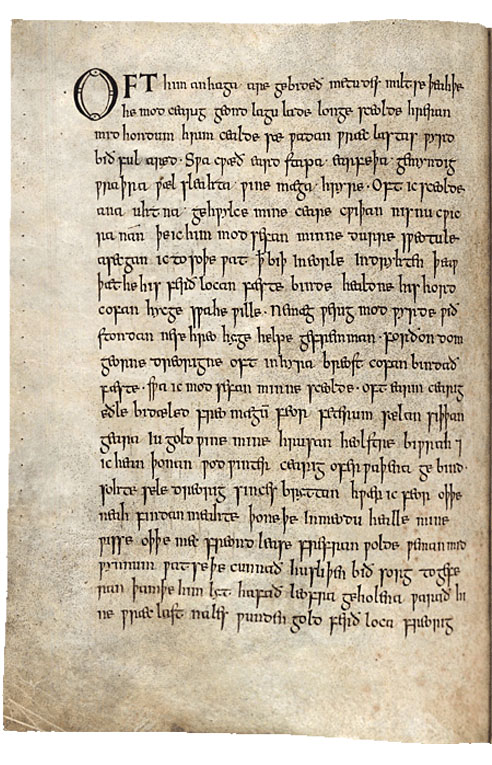

There are also similarities between the poetry of Meduseld and that which was once enjoyed by the Anglo-Saxons themselves. One famous example is “The Wanderer,” a poem of nostalgia and longing whose speaker – an old warrior who yearns to find the fellowship he once had with his long-dead comrades – delivers the most poignant lines near the end:

Where did the steed go? Where the young warrior? Where the treasure-giver?

Where the seats of fellowship? Where the hall’s festivity?

Alas bright beaker! Alas burnished warrior!

Alas pride of princes! How the time has passed,

gone under night-helm as if it never was. (120)

This is almost certainly the influence on the Rohirric lament for Eorl the Young Aragorn sings upon entering into Meduseld, capturing the same elegiac mood and borrowing almost the same lines as those of “The Wanderer”:

Where now the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing?

Where is the helm and the hauberk, and the bright hair flowing?

Where is the hand on the harpstring, and the red fire glowing?

Where is the spring and the harvest and the tall corn growing?

They have passed like rain on the mountain, like a wind in the meadow;

The days have gone down in the West behind the hills into shadow (508).

Tolkien, of course, expanded on the lines from “The Wanderer” by illustrating what would have characterized the “hall’s festivity,” using such images as the singing bard’s “hand on the harpstring” and the hearth’s “red fire glowing.”

The Dragons Awake

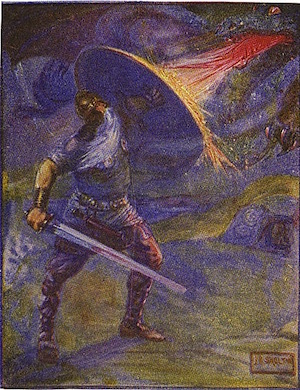

The last point worthy of note is the parallelism between the dragon Smaug in The Hobbit and that which Beowulf fights in the end of the poem. Firstly, both dragons, naturally, guard a hoard of treasure and do not cause much trouble until an intrusion. In The Hobbit, Bilbo sneaks into Smaug’s lair via the secret entrance indicated on Thror’s map. Bilbo may have been able to sneak past the dragon unnoticed had he not “grasped a great two-handled cup, as heavy as he could carry” (The Hobbit 216). Although Smaug is not immediately awoken, he is troubled in his sleep, for “Dragons may not have much real use for all their wealth, but they know it to an ounce as a rule, especially after long possession; and Smaug was no exception… He stirred and stretched forth his neck to sniff. Then he missed the cup!” (217). Immediately thereafter, Smaug launches out from his lair and wreaks havoc through both the mountain and Esgaroth.

Then there is the dragon from Beowulf. As Beowulf grows old and rules his kingdom without much trouble, a dragon is introduced:

from the steep vaults of a stone-roofed barrow where he guarded a hoard; there was a hidden passage. Unknown to men, but someone managed to enter by it and interfere with the heathen trove. He handled and removed a gem-studded goblet; it gained him nothing, though with a thief’s wiles he had outwitted the sleeping dragon. That drove him [the dragon] into rage, as the people of that country would soon discover (89).

Both dragons are thus driven from their slumber through the theft of a small goblet by a crafty thief who had no intention of provoking the destruction wrought by the monster. Tolkien himself argues in one of his essays regarding Beowulf that the dragon is “a personification of malice, greed, destruction… and of the undiscriminating cruelty of fortune” (The Monsters and the Critics 17). When taken out of context, this description could easily be attributed to Smaug, and is almost mirrored when Thorin refers to him as “a most specially greedy, strong and wicked worm” (The Hobbit 23). While the aggregation of treasure and loot was encouraged in Germanic society, to hoard it selfishly was frowned upon and considered dishonorable. Hrothgar, for instance – though the greatest and wealthiest of his dynasty – does not keep his fortune to himself. Rather he, as the text described him, “doled out rings and torques at the table” (43) and is even given the titles “giver of rings” (49) and “treasure-giver” (54). Graciousness was thus seen as a kingly virtue, and sets both Hrothgar and Beowulf apart from their draconic foe.

As outlined above, the works of Tolkien are so greatly influenced by the ancient poetry and cultures in which he was so learned. Much like Beowulf, Tolkien’s works are a style of epic just in a new form, in which heroes feast in great halls after defeating great foes, whether they be fiery dragons or hordes of Orcs. Such etymological and mythological influences are so important and even enjoyable to study as they give us further insight not only into the origins of such fiction as that of Tolkien, but into why that fiction was written. Tolkien himself wanted to write for England its own sort of mythology, intentionally giving The Lord of the Rings an ancient and almost nostalgic tone. What better way to do this than to borrow and learn from the classics? By harkening back to the Old English poems and Germanic mythology with which he was so familiar, Tolkien produced an imaginarium that presents ancient core motifs yet in a way that is both original and outstanding.

Works Cited

Beowulf. The Middle Ages. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt. Vol. A. New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 2012. 41-117. Print. The Norton Anthology of English Literature.

Thorpe, Benjamin, I. A. Blackwell, Rasmus Björn Anderson, and James W. Buel. The Elder Eddas of Saemund Sigfusson. London: Norrœna Society, 1906. Print.

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Hobbit. New York: Ballantine Books, 1982. Print.

—. The Lord of the Rings. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2004. Print.

—. The Silmarillion. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1999.

Tolkien, J. R. R., and Christopher Tolkien. The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1984. Print.

“The Wanderer.” The Middle Ages. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt. Vol. A. New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 2012. 118-120. Print. The Norton Anthology of English Literature.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Tolkien’s story is so awesome! By fare some of my favorite books to read!

I personally found parallels between the Lord of the Rings legendarium and Greek mythology. Tolkien conceived his story as taking place at the end of an age where spiritual beings for the most part held sway, and where men and other mortals were yet to reign supreme. This time was ended with an epic battle in which many heroes were slain, yet others still rose to prominence. I am of course referring to the Battle of Minas Tirith and the overthrow of Sauron. After his demise, Middle Earth supposedly made its final transition into our present world, devoid of spiritual beings like the Elves, Valar, and Wizards. In Greek mythology, the Battle of Troy functioned in a similar way, marking the end of an ancient legendarium in which gods freely interacted with people, culminating in the rise of humankind to prominence (Note: Of course we know that Poseidon harried Odysseus on his way hime to Ithica, but overall Zeus was against this and forbade his peers from interfering in mortal affairs). I always wondered if Tolkien intended for his tales to be so heavily paralleled to Greek mythos.

Yes! His work is a treasure trove of mythological allusions. It seems that so many mythologies and traditions involve the coming of a new age. In Norse mythology, for example, Ragnarok marked the end of the Age of the Gods and, when the Norse were exposed to Christianity, the beginning of the Age of the One God.

this is very late, in fact more than year late but far as i know gandalfs appearance and character is based on väinämöinen from finnish folklore kalevala

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/V%C3%A4in%C3%A4m%C3%B6inen

‘J. R. R. Tolkien

Väinämöinen has been identified as a source for Gandalf, the wizard in J. R. R. Tolkien’s novel The Lord of the Rings.[4] Another Tolkienian character with great similarities to Väinämöinen is Tom Bombadil. Like Väinämöinen, he is one of the most powerful beings in his world, and both are ancient and natural beings in their setting. Both Tom Bombadil and Väinämöinen rely on the power of song and lore. Likewise, Treebeard and the Ents in general have been compared to Väinämöinen’

I don’t think he had just one figure in mind when he created Gandalf, but several.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gandalf#Concept_and_creation

“In a letter of 1946 Tolkien stated that he thought of Gandalf as an “Odinic wanderer”.[23] Other commentators have also compared Gandalf to the Norse god Odin in his “Wanderer” guise—an old man with one eye, a long white beard, a wide brimmed hat, and a staff.[24]”

Love the Silmarillion so far. Just started reading it last week, I’m on the 7th chapter, and I wish more people would read it

I would argue you cannot fully comprehend his other Middle-Earth works without reading The Silmarillion.

Well done, this is incredible and so useful.

Thank you!

J.R.R. Tolkien was really inspired by the bible because his boook talks alot about evil vs good.

Yes, spirituality plays a great role in his work, as does good vs. evil, which I would argue is found in almost all religious texts and mythologies older than the Bible 🙂

Yes, Tolkien was Catholic.

I hope there’s a book about this History of Middle Earth.

The History of Middle-earth is a 12-volume series of books published between 1983 and 1996 that collect and analyse material relating to the fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien, compiled and edited by his son, Christopher Tolkien. The series shows the development over time of Tolkien’s conception of Middle-earth as a fictional place with its own peoples, languages, and history, from his earliest notions of a “mythology for England” through to the development of the stories that make up The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings. It is not a “history of Middle-earth” in the sense of being a chronicle of events in Middle-earth written from an in-universe perspective. In 2000–01, the twelve volumes were republished in three limited edition omnibus volumes. Non-deluxe editions of the three volumes were published in 2002.

The Silmarillion is the history of middle earth by elves perspective. also nfinished tales, lay of beleriand and morgoth’s ring. the last 2 books are really hard to find

Great article, as I love viewing and analyzing works of literature from different cultures. I would have never think to compare Aragorn to the story of Beowulf.

I am glad you enjoyed it!

I am impressed and thrilled to see that research was done into conveying the inspirations that helped to bring Tolkien’s craft to life; it is deserving to say this about your article. The extent of Tolkien’s understanding of mythology and ancient literature is often vaguely recognized, and is a part of why he was incredibly efficient to develop environments as rich as his was. There is no doubt in the ingenuity of his works, and his mastery over linguistics aided him to even construct new languages and grammar of his own to support the stories he invented. He has remained to be one of my prominent sources of education and understanding of fiction and literature.

Thank you for your kind words! I agree, both he and C. S. Lewis remain the two authors who have most moved me to study and compose literature. I do not think any writer has enchanted me as much.

Oh wow, I just started a Brit lit class, and we’re studying Anglo-Saxon literature such as Beowulf, so this article is completely relevant to such studies. I had no idea about the background of Tolkien’s studies.

In class, we spoke a lot of the honor-in-battle attitude, along with the sense of companionship–of group identity, since the Germanic people were part of tribes. There’s also piety, important for Tolkien, because of Christianization and the hope “looking to the sky” gave warriors in an elegaic time.

Great read.

Tolkien’s creation myth has a lot in common with Gnostic mythology. The Ainur are very much like the Aeons, eternal beings emanated by one God. They dwelled in the world of Light. Then one of the Aeons, Sophia, wanted to create something alone. This creature, the Demiurge, was cast into the void, because it was created without the consent of the others (cf. Aulë who created the dwarves without the consent of Ilúvatar). In the chaos of the void, the Demiurge organized the chaos matter into the physical world. He also believed that he was the highest God and that there was no other above him. The Gnostics thought that the Old Testament God was in fact this Demiurge, not the real God, the father of Jesus. Some Gnostics believed that the Demiurge was evil, others thought that he was imperfect and ignorant rather than evil.

The Silmarillion was tough to read for, English being a second language and Tolkien’s way of writing can get some time getting used to. Still very glad did read it.

So much lore and names to remember! Trying to brush up on Middle Earth lore before Shadows of Mordor.

Thank you for compiling this!

Glad you enjoyed it!

Every time I research Middle-earth, I come away with nothing but awe for the power of Tolkien’s imagination. I seriously doubt anyone will ever match what he accomplished.

He was great, but it’s not as simple as him just imagining it all from nothing. He was a scholar of languages and ancient literature, and steeped in the mythology of Europe. He absorbed it all like a sponge and created something new. So there are echos throughout from the beliefs and stories of our own heritage, which makes it even more amazing, and probably why it touches so many of us so profoundly.

Very true, very true. The fact that he basically spent his life doing what he did (philiology and Anglo-Saxon scholar, refashioning what came before into something completely new) is probably why no other writer has tried to equal his accomplishments, in my opinion. Random tangent, but have you read his recent translation of “Beowulf?” I’ve heard it’s good, considering it was one of Tolkien’s favorite written works.

Glad to see this finally got published! Everything looks great. Once again, excellent article!

Thank you, Dominic, for your kind words and for your earlier feedback! This article owes you much! 🙂

You’re very welcome. Glad I could help!

Well-researched article, very well laid-out. Thank you for the research!

Thank you for reading!

Just finished reading the Silmarillion. It’s the most powerful book I’ve read so far, and made me willing of going deeper and deeper into Arda and Middle Earth’s mythology. In my opinion it’s way more fascinating than LotR and TH, because they did not manage to give birth to the astonishment the Silmarillion gave me. Moral? READ IT, everybody!

Sauron/Mairon is the most interesting character Tolkien created, and terrifyingly complex. What finally turned him evil was his love for the world, and his desire to forcibly fix the evil in it. He’s a huge perfectionist, and his original name meant “the admired/excellent/splendid/precious (one)”. He was also known as Tar-Mairon (“King Excellent”).

Golum wasn’t kidding when he called him Precious.

And one might argue that his road to evil may represent Tolkien’s masked view that “fixing” the world is, in the end, a rather futile endeavor.

Reading “The Silmarillion” currently. It is great for recapitulating the most important facts.

This is very well done! Thank you for taking the time to do it. I love learning about Middle Earth. Again thank you!

It is my pleasure, I love this sort of research. Thank you for reading!

If they ever wanted to turn the Silmarillion into a live action, I would not do a movie, I would actually do a long running TV series, it will make more money on the long run and will allow them to tell the history of the first ages a lot better, just find a team of writers who will keep the focus on Morgoth, cause he is the highlight of the Silmarillion and for good reason. It won’t be that hard to make him into a memorable villain like the Joker

I love the melding of mythologies in Tolkien’s works. The tragedies and the love stories I’ve always viewed as very reminiscent of Greco-roman mythology, especially something like The Children of Hurin. Great article btw

I think Tokein may have been Iluvatar. The capability to create such depth, wonder and what is essentially another universe that operates on the imagination of millions of people, is nothing short of godly.

I’ve been looking for something like this for a while I’m sure it took a lot of hard work.

I hope it was a fitting end to your search 🙂

Amazing article!

Thank you!

I love how well thought out everything is in Tolkien’s work.

Nice article though I believe that Benjamin Thorpe has been proved wrong about the Edda being Saemund’s and it is more accurately known as the Poetic Edda. If you’re interested in Tolkein’s Norse influences, do look into the Ring Cycle about Sigurd – always a good read!

*Tolkien, sorry

Yikes, you’re right! I will be sure not to repeat that mistake 🙂 Thanks for the heads up!

Aw this article is so timely given what i’m writing at the moment (watch this space.) My favourite comment about Beowulf/Hobbit was from David Day’s The Hobbit Companion – “The Hobbit is the Beowulf story from the thief’s point of view.”

I’m looking forward to seeing your article, Francesca.

I would dearly love to see an episode of Doctor Who where the Doctor meets J.R.R. Tolkien. Throughout his life, Tolkien had a reoccurring dream of a great wave inundating a green land, while he stood on the crest of the wave, unable to move (In LotR he gave the dream to Faramir). He never spoke of the dream, and was shocked to discover that as a child one of his sons also had the same dream. Seems like fodder for a DW episode.

There’s so much to grasp and learn from the deep history of these novels, it’s impressive and exciting.

This is a really interesting article, it is inspiring to find another ‘Tolkienite’ here 😉

We few… we proud few 🙂

Here, here!

Of course, I meant: hear, hear! or something like that 🙂

This article is a very good primer on Tolkien’s medieval influences. Tolkien had an incredible grasp of the medieval world and I hope that this article is leading more people to delve further into the world that Tolkien created. LOTR is infinitely more interesting when you can understand the dialogue he’s having with medieval sources.

What an insightful perspective! The amound of connections you make in a cultural way was so rich. Personally, I just finished rewatching each of the Lord of the Rings movies as an adult and appreciated them much more now than ever. I know many others will benefit from your article as a supplement. Understanding how culture influences a writer is a treasured gem.

I couldn’t agree more with the enhanced appreciation of LOTR in adulthood. I am glad you enjoyed the read!

What a superb article! I like the critical, academic basis of it, yet you make it very accessible and interesting to a wider audience. I think even if I did not happen to be taking a class on Beowulf and Anglo-Saxon literature this term, I would have still found it interesting because of how wide an appeal Lord of the Rings has. Very interested to see this analysis of stories crossing centuries and cultures.

I was always interested in the comparison between Norse Mythology and the world building in “The Silmarillion.” I found that Padraic Colum’s “Nordic Gods and Heroes” is a fairly straight forward approach to telling the Odin the Wanderer stories. It has helped develop my appreciation of the story Tolkien was weaving.

I think this is very well thought out. After reading Joseph Campbell and Mircea Eliade many years ago, I became fascinated with mythos as the “land before time” and the place before cognition….the pristine Eden where the serpant was only an ominous potentiality. Have you read the new award-winning book, Laurus? It concerns itself with the “Middle Ages” of Russia…which turn out to be not as primitive as we were taught in the West.

I think this is very well thought out. After reading Joseph Campbell and Mircea Eliade many years ago, I became fascinated with mythos as the “land before time” and the place before cognition….the pristine Eden where the serpent was only an ominous potentiality. Have you read the new award-winning book, Laurus? It concerns itself with the “Middle Ages” of Russia…which turn out to be not as primitive as we were taught in the West.

There is an interesting and under-analyzed difference between Tolkien and the mythology he drew from: his POV characters are largely separated from the Norse myths he drew from. The Shire is much more English and modern in tone than the rest of Middle-Earth: hobbits check their clocks and drink tea, rather than fighting dragons and winning treasure. Tolkien wasn’t just inventing new myths, but inventing myths from a distinctly different perspective, myths which incorporated characters that had our culture and values into an ancient Norse world. I’ve heard he was inspired not just by William Morris’s translations of Icelandic sagas, but the journal of the very English Morris traveling through the wild Icelandic landscape by pony. (Burns, M. J. ‘Echoes of William Morris’s Icelandic Journals in J. R. R. Tolkien’, in Chance (1991), pp. 367–73)

I agree.

This is an interesting observation. It sounds as if you’re suggesting that Tolkien wrote about his world as if he were a hobbit imagining what kinds of adventures he’d encounter within the Norse myths. Maybe you weren’t suggesting that explicitly, but you probably get my point.

I was familiar with Middle Earth and similarities with Norse legends, etc, and of Tolkien’s background to make sense of it, but I hadn’t actually read anything comparing Beowulf to Aragorn before. Awesome! Now I have something else to look into…

When I discovered books by J. R. R. Tolkien, read Thor comics and, and listened to Melodic Death Metal bands such as Amon Amarth, I researched the meaning behind these stories. Come to find out it was based on Norse Mythology. I find it interesting just as much as Greek and African mythology. Poetic Edda is another cultural piece of literature that reflects in J. R. R. Tolkien’s books and Dwarf Runes which derive from Celtic Runes. In Texas, it is a requirement for students to read Beowulf which is a great introduction to understanding Norse mythology and the leading stories. Great article!

Thank you! I am glad it pleased!

I find it fascinating how much Tolkien draws on Norse and Anglo-Saxon mythology – it adds a certain level of authenticity and verisimilitude to the books that wouldn’t be possible otherwise. Excellent and informative article!

Having studied Tolkein’s LOTR during my undergrad, this article was brilliant to read! I definitely found the use of songs in his three books most interesting, and I’m so glad this is something you explained in this article.

I am glad you thought so! Thank you!

Very interesting article, especially the poem ‘The Wanderer’! Thank you for sharing!

Thank you! If you get a chance to read the full poem, I recommend it!

I love the world he created. Thank you for writing this

Well written and well researched article. A pleasure to read – particularly the comparison between Beowulf and Aragorn; as well as the dragon Smaug and the dragon in Beowulf. Well done!

I hadn’t fully appreciated those parallels before. Your point about Tolkien’s ancient and nostalgic tone really expresses the reason I appreciate Tolkien more than most other fantasy writers. His extensive use of different mythologies, and very specific style gives it a tone that is really hard to find in other authors. It was very interesting for me to understand more about where that tone comes from, thank you.

Middle earth is actually used to refer to the place between Heaven and Hell in Beowulf so it would probably be more likely that Tolkien took the name directly from that.

Yes, and the reason it is used that way in Beowulf is because the poem is heavily influenced by the Norse. It does, after all, take place in Scandinavia.

This is a nice article, although I would suggest caution with the ‘mythology for England’ concept. I realize that you’re not directly stating that, but this has been a hot point of argument for a long time in Tolkien Studies. Anyway, I enjoyed this article and I would suggest you take a deeper look at the Finnish Kalevala for more parallels in mythology–the Kalevala was Tolkien’s first significant work in translation and provided a major cornerstone to the story of Turin Turambar, one of the three great tales in the Silmarillion.

Tolkien’s world creation draws upon a rich history of ideas that have moved from oral storytelling tradition to written language. The connections between LOTR and Beowolf could be made at several crucial points throughout the novel. The behavior of the dwarfs as guests at Bilbo’s manor was similar to the behavior of Beowolf’s men at the mead hall. There is such a richness of mythological creatures, concepts, and architecture that many articles could be written on this subject. And these ties to mythology bring the conflicts and problems of ancient peoples, such as isolation of populations, to the attention of the modern world.

When Bard kills Smaug the dragon, he utilizes a weak spot from a previous injury. Beowulf utilizes the wounds Wiglaf creates to finish his dragon. I think there is an importance in analogy here. Overcoming the most difficult adversities and adversaries requires communal effort, as in both cases more than one individual is required to defeat the monster. There is also the importance of overcoming fear of failure, as even ‘failed’ efforts lay the groundwork for completion of a task.

I love the details you provide in this article. There are not many out there that put emphasis or acknowledge the ancient stories and the like.

Great read. I am always intrigued by the influences and allegories to Tolkien’s Middle-Earth (though Tolkien himself supposedly despised allegories). Wagner’s opera The Ring of the Nibelung is another great (part) adaptation of the Norse myths that also influenced Tolkien.P. Craig Russell does an incredible job adapting the opera into the comic form and is worth checking out if you haven’t read it! I also enjoyed your information regarding the use of songs and where Tolkien drew inspiration from.