The Space That Lies Within the Frontier: Japanese Americans & the West

In light of the publication of Nielsen’s “Asian American Consumer 2013 Report”, the aim of this writing is to convey the history of Asian Americans in consideration of the findings in the report. Specifically, my work discusses Julie Otsuka’s When the Emperor Was Divine, a novel that details the lives of a Japanese American family before, during, and after their internment during World War II. In light of the publication’s findings, I do believe this essay is great food for thought.

“Jap! Jap! I’m a Jap!” (Otsuka 76). Through such instances of declaration, Julie Otsuka uses dialogue to conceptualize the preconceived notion of the American identity in contrast to the Japanese American identity. In doing so, the counter narrative is a means of deconstructing the assimilation of the American West and the frontier myth that has endured for centuries. Rather than holding on to it steadfastly, Otsuka urges for the analysis of the fundamental convictions of the American identity. Factors of racial differences conflict with the representations of the American West because they evoke a sense of ‘otherness’ within the American society, ostracizing Japanese Americans. As ‘others’, Japanese Americans are dehumanized through the institutionalized racism and hegemony implemented by every facet of the United States government. Thus, it is established that the United States is not a space meant for Japanese Americans, historically speaking. The space that lies within the American West is not a space for people of color, thereby leading to their displacement as a means of exclusion. It is this notion that resonates throughout Otsuka’s work as she probes what lies at the surface of the defining space of American democracy.

Otsuka represents the American West as a space that can only be claimed by whites. In doing so, she introduces the family in her novel as any other typical American family might have appeared in Berkeley, California in the 1940s. The son has a “painted wooden Indian…[which he] won at the Sacramento State Fair”, the daughter has a note on her room door that reads “DO NOT DISTURB”, and the mother has “the painting of Princess Elizabeth…the picture of Jesus…[and] a framed reproduction of Millet’s The Gleaners” hanging on the walls of her home (Otsuka 7-8). This demonstrates that despite their ancestry, the family has culturally assimilated within Western society so that they share the traits of almost any of their neighboring families in the city. However, their assimilation can never make them indistinguishable from other families within that society because of their Japanese ancestry. This is revealed when the daughter asks her mother if there is something wrong with her face because when she is outside, people often stare at her (Otsuka 15). The family’s partial cultural assimilation within their society does not equate them to the level of integration inherent within their neighboring white families because it is only the Japanese family that is relocated to an internment camp. While there, the son “thought he saw his father everywhere….for it was true, they all looked alike..[unknowable]..[inscrutable]” (Otsuka 49). Outside of the internment camps, the family was easily distinguishable based on the racial markings of their bodies. They were the ‘others’ and perceived as people who did not belong within the space of their community and, for that reason, a forced removal ensued. Contrariwise, within the internment camps, they were no longer distinguishable. Everyone within the camps shared such similar facial features that, to the young boy, he believed every man he saw was his father.

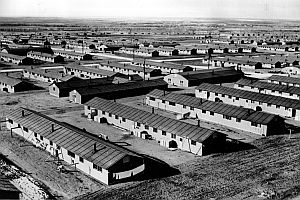

Unlike Berkeley, the internment camp was where the family was able to fully assimilate, thus connoting that when a person looks a certain way and have the features of a Japanese American, they are subjugated to forced removals and the experience of losing their autonomy. As Japanese Americans, the members of the family cannot claim any space within the American West other than that which is given to them. Such powers are beyond their reach because they are not white. Rather, the emergence of an inferiority complex and self-loathing develops as the family comes to be ashamed of their own reflections in the mirror, believing that they were a guilty, dangerous people who could never be trusted again (Otsuka 120).

Further, Otsuka highlights the family’s partial cultural assimilation into Western society as a narrative strategy to substantiate how, as people of color, their ancestry prevents them from undergoing full assimilation. The racial contrast differentiating them from whites echoes throughout the city as “the sign that [reads] INSTRUCTIONS TO ALL PERSONS OF JAPANESE ANCESTRY went up all over town and they packed up their things and they left” (Otsuka 76). Validated as people not meant to inhabit the space that lies within the American West, the family spent years in the internment camp and, upon their release, only small remnants remained of their sense of identity. They performed “without thinking” and “as though they were still in the mess hall barracks” (Otsuka 111-113). The family lived in the past, contemplating how much differently their lives had been before their forced removal. Stuck in time, their identities were loss as they became engulfed by the haunting of the war. In fact, they were stuck in time so much that sometimes the mother did not know whether she was awake or asleep (Otsuka 94). The time they spent in the internment camps left the entire family in a state of paralysis. Josephine Park argues that “[in] the camps, they desperately held on to prewar memories, but back home, they cannot forget their incarceration…as [it] continues to shape their lives” (Park 148). Frozen in a trance-like state of being, their adjustment outside of the internment camp back to the lives they had been forced to leave behind was no small attempt.

Extending beyond the mere representations of the American West, When the Emperor Was Divine reveals the subversion of minority groups on a massive scale, all resulting from the notion of the frontier myth. When it is addressed in regards to its historical context, the space where the family forcibly relocates evokes images of the American frontier at its present state and in retrospect to its past state as the dwelling place of Native Americans. Before their first contact with Native Americans, the “colonists” and “pioneers spread westward, spurred on by notions of manifest destiny. The “colonists” and “pioneers” believed that it was their God-given right to expand for the progression of the country into unknown territories. The presence of displacement of minority groups and institutionalized disempowerment in this particular space of the American frontier signifies repeated acts of subversion. As people of color, both Native Americans and Japanese Americans are unable to claim spaces within the American frontier that they inhabit because as non-whites, they are denied this luxury. Embedded in the portrayal of these images is the “reality of genocide…obscured beneath the palimpsest of the mythic Indian and the mythic American national story” (Bayers 46). The frontier images “suggest that the movement west did not signify imperial expansionism and colonialism, nor did it mean the genocide of Native peoples on the North American continent” (Bayers 49). Rather, the images suggest that “the United States remains an ”exceptional” nation, freed from the reality that the United States was and is a colonial nation that conquered and committed genocide against Native peoples” (Bayers 50).

Additionally, the concepts of rugged individualism and the perception of the cowboy are undermined in the novel as Otsuka’s means of disillusioning the façade of the frontier myth. In doing so, Otsuka deconstructs the frontier myth through the portrayal of the father’s return from the internment camp. Upon his return, the father “[looks] much older than his fifty-six years” and has “lost the last of his hair” (Otsuka 132). Beyond his physical appearance, the father of the family is also a different man in terms of his mentality as “always it seemed, he had something else on his mind” and “[little] things…could send him into a rage” (Otsuka 134-135). Haunted by the traumas he endured in the camps, the father returns a paranoid skeptic. Damaged by his former experiences, the father, like the rest of the members of the family, becomes stuck in time. He cannot move forward with his life or continue his life in its present state. Moreover, he is unable to maintain a grasp on what has become his reality. He constantly “[needs] to see [his children’s] faces…[otherwise] he would never know if he was really awake” (Otsuka 133). The father sits on the “edge of his bed with his hand in his lap, staring out through the window as though he were waiting for something to happen” (Otsuka 137).

The father’s behavior undermines the concepts of rugged individualism and cowboys because the father is not portrayed as a fearless person whom dominates his environment, nor is he the sole dictator of his own fate. Cowboys, on the contrary, inhabit “a vast and stunning landscape” where they are the “very pinnacle of masculinity” (Sohn 175). The father never pulls himself up by his bootstraps and gains control of his depraved state of being. Rather than acting as a dominant force, he holds no claim to any space and is unable to grant himself security in any place that he exists. He disassociates himself from his family, referring to them as “you people”, just as he has loss his sense of identity and has been disassociated from his own true self (Otsuka 137). Therefore, all of the father’s traits undermine the concepts of the cowboy and rugged individualism. Otsuka sharpens the contrast between these particular aspects of the American “frontier ideals” and the harsh realities of the father’s dismembered livelihood because doing so certifies that, at its core, the American frontier and all that it represents is derived from nothing more than myths. This indicates that the American frontier is founded upon lies, and fallacies. If this was not so, the American “frontier ideals” would apply to all Americans, regardless of their ancestry.

Julie Otsuka’ novel When the Emperor Was Divine epitomizes the willingness that spurs people of color to ascend in social mobility. While it connotes that any person of color can potentially become the ‘other’, the novel also acts as a form of resistance toward American frontier ideologies. In doing so, it disrupts the myths of master narratives. Written by a person of color, the counter-narrative deviates from national myths, thereby creating a space within the American West intended for the inclusion of people of color. That space lies within the novel itself because simply reading it is acts as a form of upward mobility against the subversion of people of color. Within this space, people of color must consider how the politics of truth shapes their American history. Since America tends to function as a nation-state rather than a unified nation, the cultural assimilation of people of color into the nation is influenced by how they respond to the indecencies they were forced to endure.

Rather than being defined by the past and accepting the frontier ideals, Otsuka connotes that individuals must create their own space. In this space, they will have the power of extinguishing the silence that has barricaded people of color, creating an alternate means of challenging what has been proclaimed by people in power. The accounts of people in power merely reflect the politics of truth. This tends to result with the emergence of fabricated concepts such as the frontier myth. When the Emperor Was Divine breaks the silence inflicted upon people of color, allowing Otsuka to claim a space within the American West from which she cannot be displaced. She cannot be displaced from this space because as a Japanese American, as a non-white and as a person of color, she belongs in that space.

Works Cited

Bayers, Peter L. “The US Mint, The Lewis And Clark Bicentennial, And The Perpetuation Of The Frontier Myth.” Journal of Popular Culture 44.1 (2011): 37-52. SPORTDiscus with Full Text. Web. 21 Sept. 2013.

Hayashi, Robert T. “Transfigured Patterns: Contesting Memories At The Manzanar National Historic Site.(Manzanar National Historic Site).” Public Historian 4 (2003): 51. Academic OneFile. Web. 6 Oct. 2013.

Otsuka, Julie. When The Emperor Was Divine. New York : Anchor Books, 2003. Print.

Park, Josephine. “Alien Enemies In Julie Otsuka’s When The Emperor Was Divine.” MFS: Modern Fiction Studies 59.1 (2013): 135-155. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 21 Sept. 2013.

Sohn, Stephen Hong. “These Desert Places: Tourism, The American West, And The Afterlife Of Regionalism In Julie Otsuka’s “When The Emperor Was Divine”.” Modern Fiction Studies 55.1 (2009): 163. Biography Reference Bank (H.W. Wilson). Web. 21 Sept. 2013.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

To me, When the Emperor Was Divine is a long poem written in a book form. she is an excellent novel but, i am quite disapointed because there seems to be so litte backgroound information on her. i think this story is great and anyone so says opposite should be ashamed

I too am fascinated with the novel because it provides such an intimate account on how institutionalized racism wrenched a family apart from the inside out. In this way I suppose it does have a poetic quality to it.

Thanks for the comment!

I remember that I dearly loved two different Japanese-American families who were our good friends right after the end of WWII. I was just beginning to become aware of family and friends, and I was always told that these particular people from California had lived with us “during the war” (a time before I was born). Later I learned that it had something to do with keeping them out of “camps,” but it was many years before I realized that my parents had employed and sheltered Japanese- Americans so that they wouldn’t be confined in some awful barracks out in the Utah desert. Eventually, I learned the historical context of this personal memory and came to understand the enormity and irrationality of the hysteria that caused it. More and more writing about it has recently appeared, but the quality of the writing, particularly of fictional treatments has been mixed, to say the least. Finally, this is a really truthful and beautiful book about it and I am so grateful that my children and grandchildren will have this excellent account of what happened and how it felt to so many innocent people. Also, because of this book they will be able to appreciate that their grandparents (or great-grandparents) objected at the time and actually tried to do something about it. Heartfelt congratulations and thanks to Julie Otsuka for this luminous work of art and thank you for spreading the awareness.

Thank you so much for this comment. I believe it’s quite telling of the perils of that time. Moreover, I agree that this information must be passed on in remembrance of those who came before us. This information is significant to people regardless of race & ethnicity.

Thank you again for this great comment!

Very well written article, thanks for the read.

It was my pleasure! I am glad you enjoyed it.

Asians tend to value education, and have high expectations.

The Suburbanite helicopter parents, by contrast, make excuses for their precious snowflakes, value mythology over science, and blame teachers for their children’s mediocrity.

It’s no surprise that Asians have catapulted ahead. They deserve it.

Interesting. I try not to generalize by applying specific traits to an entire group of people but I do agree with your implication that hard work pays off.

Thanks for the comment.

Julie’s little book is one of the most powerful I have ever read.

Yes, the novel is most definitely a fantastic read. I’m glad you enjoyed reading it as much as I did.

Thanks for the comment.