The Thin Red Line: The Impact of the Senses on Setting and Landscape

As part of the Criterion edition of the film, a message appears on the screen once the play button has been pressed: “Malick recommends that The Thin Red Line be played loud.” There is enormous weight to that seemingly simple message: that a normally reticent director would attach a recommendation (adorned with his name) to the beginning of this film speaks to the significance he attributes to its sensory nuances, particularly its auditory cues. Indeed, from the very first shot, of a slowly submerging alligator, our senses are tested: the musical chord preceding and lasting throughout the alligator’s movement is loud enough to make one reconsider Malick’s recommendation. However, pay heed, for it is this attention to senses and auditory cues that ultimately allows Terrence Malick’s 1998 masterpiece of a film to fully transform notions of filmic setting and landscape.

The Thin Red Line tells a fictionalized version – focusing on a battalion of American soldiers – of one battle during the Guadalcanal Campaign in the Pacific Theater of World War II, but what distinguishes it from other films about war is that it seems to focus on the subject indirectly. Indeed, the film was released the same year as Steven Spielberg’s more popular, and more violent, Saving Private Ryan, and in many ways offers a stylistic counterpoint to the focus on action in Spielberg’s film. Malick’s camera wanders around the natural world as often as it focuses on specific characters, and it digresses from the current temporality, character, or place with little regard for standard continuity editing. This is typical fare for a Malick film, and it creates a work that is both elliptical and fascinating.

The disparate temporalities, characters, and places are connected by the numerous character voiceovers, which are never explanatory and always lyrical. The film’s images often seem to acquiesce to the musicality of these oblique voiceovers, and we are rarely sure whether the shots of natural settings and landscapes are from a character’s point-of-view. They could just as easily be said to be projections of the speaking character’s imagination, projections of non-speaking characters, the visions of a god-like presence within the film, or perhaps just the evidence of Malick’s auteurist hand. Whatever the case, the images are the crystallization of character, setting, and landscape, and they derive potency through the film’s sounds.

Before Malick, an interesting distinction between filmic setting and landscape had been spelled out by Martin Lefebrve, who states that transference of setting to landscape is brought about by “the interruption of the narrative by contemplation,” which in turn “has the effect of isolating the object of the gaze, of momentarily freeing it from its narrative function” (“Between Setting and Landscape” 29). Essentially, under Lefebrve’s definition, what separates landscape from setting is the viewer’s gaze. By gazing at and contemplating the moving pictures, the viewer adds a temporality to the already illusory temporality inherent in the cinematographic medium.

As a result of this doubly temporalized interaction, the film’s setting, which is normally part of the narrative, occasionally shifts to landscape when it is contemplated not in the temporality of the film but in the temporality of the viewer’s mind. What is striking about Lefebrve’s definition is how important “interruption,” or intrusion, is to transformation of setting to landscape. Of course, if setting can be transformed into landscape by “interruption,” it should follow that landscape can be transformed back into setting by the same break of continuity. Additionally, if the setting and landscape are constantly shifting back and forth, they must also be wrestling the viewer in and out of “narrative mode” and “spectacular mode” (29).

In their essay “‘One Big Soul’ (The Thin Red Line),” Leo Bersani and Ulysse Dutoit, like Lefebrve, attach tremendous significance to the act of looking or gazing. For Bersani and Dutoit, close-up shots of a character gazing is the key to understanding Malick’s ambiguous work.

But to make The Thin Red Line into a silent film – as they take to be a legitimate possibility – would be a grave error (146). Without alternating moments of temporal disjunction and unification, the film would be unable to create space between character and immediate setting; in a soundless The Thin Red Line, viewer and character contemplation would be rendered nearly impossible and any semblance of the film’s intellectual activity would be erased.

Uniquely, instead of the act of gazing, the primary method of interruption in Malick’s The Thin Red Line is the act of hearing. Using both voiceovers and music (often intermingled), the film wrests the viewer out of the filmic space of the current narrative, allowing him/her to contemplate either a character’s flashback or the image of a character himself contemplating. Nearly every moment of intrusion by non-diegetic sound – whether it is a piece of music or a non-linear voiceover on top of unrelated images – serves to add an additional temporality to the cinematographic temporality of the images over which it is played. In doing so, the film allows contemplation, and thus “spectacular mode,” to occur. What is so striking about The Thin Red Line, then, is that in terms of distinguishing between setting and landscape, the senses – with particular emphasis on hearing – play a pivotal role.

As Bersani and Dutoit note, one of the primary oppositions set up in terms of both character and psychology is the relationship between Witt and Top (147). Top’s belief that there “ain’t no world but this one” flies in the face of Witt’s insistence that he has seen another. To Top, since our one and only world is blowing itself to bits, all a man can do is “shut his eyes” and “let nothing touch him.” Not only does this suggestion run entirely counter to Witt’s mode of constant, open-eyed observation, it also betrays Top’s aversion to sensical contact. In closing off both sight and touch, Top hopes to find a “bliss” in numbness that he has yet to feel as a soldier. Top’s aversion to sensical contact is a luxury which Colonel Tall does not have.

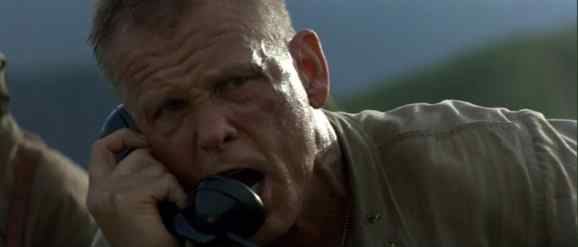

The Lieutenant Colonel’s stubborn nature is due to lack of sense rather than hopeful avoidance of it. Tall’s inability to see the proper means by which to attack the Japanese stronghold on the hill is reflected in his mentioning Homer to Staros on the phone; foreshadowing their future showdown, Staros is more concerned with the welfare of his men than the high rhetoric of someone also known as the ‘blind poet’.

Early in the film, John Travolta’s Brigadier General character reminds Tall that there is “always someone watching,” and to act accordingly. The colonel takes this advice to heart, for he becomes obsessed with image and appearances, often to dreadful effect. He chooses to bomb the hill in a random area so that the sight of explosions in the distance will “buck the men up,” even though this action only frightens them; while on the phone with Staros, he pretends to be receiving good news about the Allied attack in order to give those around him a positive state of mind, but only confuses Staros; on the phone again with Staros, this time surrounded by a retinue, he refuses to allow Staros’ altruistic recommendations to take precedence over his own orders; he yearns to decorate Captain Gaff in order to consolidate the argument for his foresight in naming the Captain leader of the attack group, but by doing so refuses to allow Gaff to give credit where credit is due; he does not want to record Staros’ relief of duty as subordination because of how it might “look” to the higher-ups, instead leaving Staros with the guilt of owning an undeserved Purple Star. This relationship between sensical deprivation and character shall be played out in the film’s (arguably) main character.

Right from the outset, Witt, through his voiceover, is positioned as a character heavily interested in sensical issues: “I heard people talk about immortality, but I ain’t seen it.” The dichotomy set up between what Witt hears and what he sees serves as the germ for much of his and others’ subsequent actions and voiceovers. What the viewer sees versus hears is also interesting to note. That which Witt contemplates in voiceover often is directly opposed to the violent actions (his included) seen in image form on the screen. As Bersani and Dutoit note, Witt’s plea at the end of the film to look out through his eyes at “all things shinin’” uses “words that nearly the entire film contradicts” (142). Although nothing of what we see is necessarily shining – and in fact, the only other time the word “shining” is heard occurs in a heartbreaking scene where Bell reads his wife’s letter, in which she cruelly asks him to remember the “shining years” and help her leave him – to look out through Witt’s eyes is different. He only cries once during the film (as he returns from the village to meet up with Charlie Company), and those tears are more out of overwhelming positive emotion for the brotherhood of his company than pain or sadness. He does not feel the same grief in encountering death that others around him feel, for at any given encounter he is more interested in discovery than despair.

What Witt seems to be searching for in others is the same “calm” that he saw in his mother as she died — his search entails several seemingly inconsiderate but in fact only curious confrontations with those on the verge of death. In the confrontations, we are given a close-up shot of Witt as he silently gazes. It is this image of a curious, contemplative gaze that draws so much of Bersani and Dutoit’s attention; however, in actuality, the contemplation manifests itself more sonically than visually. His sense of calm around death appears to arise because every time he encounters it, the viewer (and probably Witt as well) is able escape the temporality of the situation, primarily due to music but sometimes due to a voiceover. The beginning of a soft tremble of music that begins to play in the background of Woody Harrelson’s death coincides with a close-up image of Witt gazing; as Witt observes the dying Japanese after the Allied raid, a voiceover takes the place of their diegetic screams; the beginning of a soft tremble of music in the background of the death that has reached the village coincides with a close-up image of Witt gazing.

Even his own death serves as an example. Eventually, Witt finds contemplation to be the key to the “calm” in his mother. For him, death (his own in particular) begets a moment of contemplation. Just as the viewer is treated to temporally disjointed music during Witt’s gaze at death in order to interrupt the narrative with contemplation, at the moment directly before raising his weapon Witt hears the the sound of rushing water. It is as if in this final moment of his life – when his body is on the verge of nonexistence – he finally understands that contemplation is the calm he saw in his mother, and in order to contemplate, he triggers something temporally disjointed (the sound of the rushing waterfall he bathed in with the villagers) from his current narrative so that he may escape setting and fully integrate into the landscape he prods with questions yet yearns to be a part of.

The most effective means by which the film distinguishes between setting and landscape is – just as in Witt’s death scene – through the manipulation of diegetic expectations. The only truly diegetic voiceover occurs when Doll shoots a Japanese soldier. In a direct voiceover, the pure exhilaration of Doll’s external boasts to a fellow soldier juxtapose with his calm, almost teasingly hypocritical, internal thoughts: “I killed a man… the worst thing you can do. Worse than rape… I killed a man and nobody can touch me for it.” In this scene, there is no music and the volume of the voiceover does not dwarf that of the external dialogue like it does at other moments in the film. The uniformity and immediacy of Doll’s internal thoughts prevents the viewer from escaping the temporality of the image. At no time during this scene can contemplation occur, and at no time does setting transform into landscape for the viewer or Doll.

The only truly diegetic piece of music is more complex temporally: the song that the Melanesian villagers sing right before the Navy ship appears in the distance. The first time it is played actually seems to be non-diegetic, for it is played on top of unrelated images of Witt walking into the village from the beach. It is soon shown to be diegetic, however, when we are given a shot of the villagers marching slowly whilst singing the song. Interestingly, we are actually fed into this diegetic occurrence by a non-diegetic, orchestral version of the very same village folk song. The images which correlate with this orchestral version include Witt and a fellow soldier playing with the children, and later, a close-up of Witt silently observing something offscreen: this recurring image almost gains leitmotif status as the film progresses, and it often is juxtaposed by what Bersani and Dutoit call the “musical voice motif” of Witt’s voiceovers (138). Similarly, the non-diegetic, orchestral version of the song lends itself to contemplation, and thus landscape, due to the off-kilter temporalities of the music and the images over which the music plays. In contrast, when the the diegetic song appears during the shot of the walking villagers, the mouths match the song, and the temporalities of image and sound are united in the narrative. This universality of narrative is highlighted by the fact that, as opposed to Witt being separated from that which he observes during the non-diegetic version of the song, he can actually be seen behind the villagers but still within the frame during the diegetic version.

That contemplator (Witt), contemplated (villagers), and music (song of the villagers) all come from the same image attests to how Malick uses the offscreen: cases contrary to the single image example – for instance, the numerous shots of non-diegetic music played over an image of Witt gazing at that which the viewer is not able to see – create cinematographic space between the character and the setting around him, which in turn creates space for contemplation between the viewer and the narrative which is unfolding on screen. Alternately maintaining and dissociating the temporal integrity of the film’s narrative, Malick appears to use auditory cues to signal the transference of setting to landscape, narrative to spectacle.

Curiously, the song which was first non-diegetic, then non-diegetic but orchestral, and finally diegetic, is taken back into the soundtrack as a non-diegetic piece of music two times later on in the film. The first of these occurs directly after Witt has given water out of his own canteen to a plant he notices beside him. As a close-up of rippling water fades away, in comes the Melanesian song, and what follows visually is a flashback to when Witt was AWOL with the villagers. Here is an example of what might be called a ‘thought-line match,’ an event that actually seems to appear just as frequently in The Thin Red Line as eye-line matches.

The second is at the very end of the film: as the image of two coconut shoots rising out of the water begins to fade away, in rolls the Melanesian song along with the credits. It is the only diegetic music in the entire film, and it is repeated (in various forms) five times throughout The Thin Red Line, most notably at the very end of the film.

What are we to make of this? Certainly, the outro music contrasts sharply with the intro “music” – a chord more noise than melody. The Melanesian song is both organic and appealing in its melodiousness; the chord over the image of the submerging alligator is neither. But before tackling the relationship between the sounds which cap the film, it should be noted that immediately prior to the outro song, the same sound of a rushing waterfall heard earlier when Witt is killed reappears – that this sound does not match the serene tide around the coconut shoots points to a similarly non-diegetic genesis. In placing this non-diegetic sound of rushing water over both the image of Witt’s death and also the image of the coconut shoots, Malick highlights the uniformity of Witt and the landscape which death has allowed him to first contemplate and then integrate into.

As Bersani and Dutoit are sure to mention, the numerous allusions – both auditory and imagistic – to water are integral to the film (170). In addition to the moments they note, at an early point in the film, we are treated to a shot of Melanesian children swimming under water. The very next shot, as if it is a ‘thought-line match.’ is our very first view of Witt: he is rowing in a canoe on top of the water, peering into the depths below him. While Witt rows towards us, two villagers on a canoe pass behind him. As viewers, we are privy to the image but not the diegetic dialogue between Witt and these two villagers – we see Witt’s mouth move but we only hear the separate temporality of the soundtrack. In this moment, by means of disjointed sonic temporalities, Witt seems to be too busy contemplating the spectacular landscape he exists in to fully register the diegetic dialogue within his immediate setting.

Our very last image of Witt is drastically different from this first image, for instead of gazing at and contemplating what may or may not be his mind’s image (the Melaesian children swimming underwater), he is completely submerged under the water with the children. During the entire final sequence, neither Witt nor the children are shown breaching the top of the water. This movement from distant observation of the water (Witt is completely separated from the water by a canoe) to complete submersion couples with the alligator’s earlier movement from land to complete aquatic submersion at the beginning of the film. It seems that, after a lifetime of gazing, of contemplating, Witt has finally heard the rush of water, finally “felt” in a way that only the natural act of aquatic submersion can make one feel, the glory which he seeks. It is at this moment of total sensical immersion that he can simply, as Bersani and Dutoit suggest, “take in what [he] sees” and abolish the “distance” between him and the landscape on which he rests his gaze (160).

As we are shown in a flashback, Witt’s sister finds solace in first reaching out for her mother, then actually feeling the fulfillment of an immersive embrace. Her face in the embrace exudes contentment due to the sensical mode of encountering death she chooses to use. The POV shot, which we assume to be Witt’s, is both limited and leads to his curiosity because it is a vantage point which witnesses but stops short of feeling; this distanced interest is reflected in the elliptical voiceover attached to the scene, as well as subsequent moments where Witt gazes at those who are dying. At the moment when he points his gun to the sky and accepts the spray of bullets, it is then that he realizes that he too must feel death, not only witness it, just as Top claims that some can “feel the glory of a dying bird.”

Works Cited

Bersani, Leo, and Ulysse Dutoit. “‘One Big Soul’ (The Thin Red Line).” Forms of Being: Cinema, Aesthetics, Subjectivity. London: BFI, 2004. Print.

Lefebrve, Martin. “Between Setting and Landscape in the Cinema.” Landscape and Film. Routledge 2006. Print.

The Thin Red Line. Dir. Terrence Malick. Perf. Jim Caviezel, Sean Penn, Adrien Brody, George Clooney, John Cusack, Woody Harrelson, Nick Nolte, and John Travolta. Twentieth Century Fox, 1998. DVD. Criterion Edition.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I must say that Thin Red Line is the best war movie I think I’ve ever seen. I haven’t felt like I understood what war was really like until I saw this film. Part of the reason is that I felt like the characters weren’t hell-bent on defining themselves as characters, and remained human throughout the whole film.

The film should have been titled “Reflections of a Dead Man” for it was the philosophical musings of a soldier about the harshness of war and the meaning of life who ultimately is shot at the end of the movie. This contradiction is, by itself, enough to cause the viewer to pause and think that this narrative vehicle just doesn’t work.

Either he is alive and facing the existential questions of life in the midst of a hellish war and therefore, understandably confounded by the meaning of life, or he is dead,and, given the films implication of the belief in an afterlife by the narrator, he should hopefully have found out the answers and not be so troublingly confused. Add to that the sometimes pedantic and pseudo-philosophical mush that he expresses, and it just adds to the surreal disconnect so aptly described by Ebert.

Even the plot line had its faults, for the fact that narrator-soldier saved the platoon by causing the Japanese garrison that surrounded them to follow him away from his platoon should have been obvious to the men, but was never brought out in the film when the soldiers established his grave marker.. Furthermore, it was obviously an act of love on his part to put himself in a position where he would likely be killed in order to allow his wife to remarry, a concept which could have been more clearly depicted.

The movie is visually captivating and there were stellar performances by several including Nolte and Penn, but overall it gives the impression of a director who is overwhelmed by how incredibly deep he thinks he is and expresses that through the effusion of philosophical pap and a good bit of drivel through the voice of the narrator.

I like that you’re trying to write a real criticism. You’re almost there. But you lost me when you called his musings “pseudo-philosophical.” The questions he is asking are deeply rooted in philosophy, as old as time, and they are obviously important to this director and countless people. The voice-over technique is polarizing, and I get that, but don’t deem it fluff just because you do not find the beauty in it that others do. (Also, it wasn’t Caviezel’s character whose wife was leaving him, it was Ben Chaplin’s)

this film is beautiful, although not a complete anti-war film, it is still beautiful. the shots of the fields, and the multicoloured birds are amazing. for all this, i thank you Terrence Malick

Strong analyses, thank you. The photography in this picture is amongst the most beautiful and artistic ever to be seen, the stark contrast between nature’s beauty and the evil of war is thought provoking.

This film is one of those greats which can absorb you entirely if you let it.

Hans Zimmer’s best score in my opinion, just brilliant.

It achieved a greater sense of how war is Hell without resorting to the pornographic violence that opened Saving Private Ryan, the other WWII film of that same year, with some top notch performances from such a hugely expansive ensemble.

I once heard someone say that Saving Private Ryan was made for the eyes while The Thin Red Line was made for the soul. While I certainly think that person is being a bit narrow with their observations, there is still a bit of truth in that.

Spielberg’s picture is rightfully remembered for showing the carnage and viscera that scatter a battleground during an engagement, and I find it a bit dismissive to simply label it pornographic. I don’t think it was meant to be a gorefest akin to those produced by Eli Roth and Rob Zombie but an honest look at combat. Bear in mind many veterans praised Spielberg for being so honest about what it’s like and not shying away from showing just how grotesque battles are like. In this sense, I’d say Spielberg did an excellent job of showing how war is Hell through a purely visual method.

I would agree, however, that The Thin Red Line has a very different method of presenting the adage that war is Hell, mainly through the contemplations of the soldiers who endure it. The “great evil” speech that we hear during the raid on the Japanese village is brilliant and focuses more on the impact of combat in a spiritual sense rather than just a visual sense. It is unique and provides a great counterpoint to Spielberg’s film.

Truthfully, I don’t think I can pick one over the other simply because they are executed perfectly for what they are trying to accomplish. Spielberg created a fairly traditional war film which focused on the brotherhood that develops between soldiers during war while also presenting combat in an unvarnished manner. Malick showed the cacophony of emotions and thoughts that occur within a soldier at any given moment both inside of combat and outside of it.

It’s one of the worse movies I’ve ever seen. Those combat scenes are practically one-second shots welded together rather than proper choreographed battle and the morality is hilariously tries to cough up (someone shoots an enemy in combat then thinks to himself “I’m a murderer, worse than a rapist”) is shameful and pointless beyond imagination.

I’ve never known what to make of Terence Malick’s pictures and perhaps that’s why I’m so drawn to them. His first three films plus The Tree of Life are so meditative and abstract (in a good way) that they manage to create a rather lovely bridge between ideas and actions. On a lesser note I found that I disliked The New World and To the Wonder on the grounds that they were to distant and didn’t provide the viewer with enough of a connection to the themes and characters.

Anyway, I thought this was a very insightful analysis of The Thin Red Line Zico. As you said, one of Malick’s staples is that he relies heavily on sensory details to both provide a sense of time and place as well as a meditative atmosphere where the audience can fully grasp the emotions that the characters are feeling. For me, one of the most intense scenes in the film is a brief moment during the charge up the hill. Amidst the explosions and gunfire we see a baby bird, wounded horribly, moving through the grass. This shot of an innocent element of nature is more effective in eliciting sadness than most diatribes, and it’s a testament to what I’d call Malick’s Poetic Eye.

Though I can’t quite say that I looked into the film as deeply as you did and took a number of things at face value, I still think this is a very passionate and insightful into one of cinema’s most abstract masterpieces. Really good job Zico.

Nick Nolte deserved an oscar for the role.

This is the best war film since Apocalypse Now.

This is one of my all time favourite War movies ever.

This makes me note that I have to rewatch this masterpiece sometime soon.

Truly an absolute masterpiece, Mallick’s movies are so beautiful and memorable and stick in your mind long after seeing them. One of, if not my favourite war film. The combat scenes are tense and traumatic and very realistic.

I watched this for the 1st time a few weeks ago and thought it was terrific.

Haven’t seen this film since VHS release. Might be worth revisiting, but I remember being seriously disappointed with it. But I’ll give it another try after reading this.

This great film sends out an even greater message and is a good depiction of war. I was moved by this film and it made me realise how emotionally intense, touching, tragic and horrific war can be .

Awesome analysis! It’s also interesting to note the conflicting opinions regarding this film in these comments. Goes to show that enigmatic or abstract artwork can spark great discussions.

This was a good movie and your essay did a good job discussing it. My father fought in the Pacific Theater of Operations during the Second World War, so while watching this movie I was wondering what he went through at the time.

Definitely interesting to hear of a film living in Saving Private Ryan’s shadow.