Urban Fantasy’s Unique Female Hero

A primary characteristic that separates urban fantasy (UF) from other fantasy subgenres is the protagonist. Perhaps more than any other genre, fantasy narratives are focused on the journey of the protagonist or, more commonly, the journey of the hero. UF can be categorised as fantasy literature, film, television, comic, etc. that situate a fantasy narrative within an intensely urban environment. The city landscape is contemporary, with all the relevant technology and complications of our modern lives, yet is also home to a myriad of supernatural and fantasy creatures that lurk beneath the surface. A further emerging characteristic has been the focus on the use of female heroes in a manner that is quite unique within fantasy literature.

UF is a subgenre rich in heritage. Like any type of fantasy fiction, it draws on ancient mythologies and follows a recognisable pattern of the heroic quest. From its heritage of urban realism, via the gothic, horror and city authors of the nineteenth century, it embraces the urban as the heart of UF. Necessarily then, the key character—the protagonist and hero—has developed as a unique amalgamation of urban realism and fantasy. The UF protagonist exists in a real-world urban setting, with all the expected pressures and freedoms of modern city life, while also facing an incursion of the non-rational and supernatural. Their role is to lead the reader through this labyrinthine landscape of real and unreal, brushing against horrors and wonders. As a hero, they must face the horrors and find resolution. Added to this burden are the complications of gender. UF is female-centric; thus, the UF protagonist tends to also be female, with all the burdens of gender expectation. Bound by the realism of UF, the female protagonists are not Amazonian warrior women, but contemporary women—unique individuals thrust into an extraordinary situation. An example is seminal author Emma Bull’s character Eddi in War for the Oaks, 1 who is a musician in tune to the city, yet always on the outside waiting for a moment of greatness.

The changing female hero

UF is a predominantly female-centric literature, as the subgenre is primarily written by women, for women, about women.[1] The necessary development of the female hero is as much a part of fantasy as the continuing existence of the alpha male hero. To an extent, the role of a heroine is fulfilled in the same manner as the orphaned child hero in fantasy literature—it addresses the need to see strength in vulnerability during periods of unease or unsettlement in a society. These individual heroes are a vital part of exploring cultural understandings. While the traditional hero acted as an everyman, the contemporary fantasy hero more often stands outside or at the lowest point of the social hierarchy. This asocial character has the opportunity to press against the edges of social expectation. For female protagonists, this is a complex issue. It is not as simple as saying that, because a hero is female, they are a successful depiction of aspiration and self-criticism.

Approaching a feminist discussion in literature has become akin to attempting to discuss Shakespeare; there is such a plethora of voices adding to feminist theory that it is almost impossible to know where to begin. However, because this is not the focus of my discussion, I am going to attempt to neatly side-step this by directing readers to Marleen Barr’s Alien to Feminist: Speculative Fiction and Feminist Theory. Barr commented extensively on the changes occurring in speculative fiction (which abuts fantasy literature) in the late 1980s, which corresponds to the development of UF. She stated:

Speculative Fiction has in recent years been enlivened by the contribution of new female (often feminist) voices. Because these writers are not hindered by the constraints of patriarchal social reality, they can imagine presently impossible possibilities for women. Their genre is ideally suited for exploring the potential of women’s changing roles. 2

Barr linked second wave feminism and emerging female authors and their female characters. Although her text centres on speculative fiction, there are notable parallels that can be drawn to the expectations placed on female characters. The female warriors of this period are interestingly urban in character:

Women who succeed in both their professional and personal lives must be superior to men and must fit their roles as nurturers within the definition of ‘careerist’ which does not quite include ‘mother’, ‘wife’—or even ‘female’. The mother and wife who does excel professionally receives special acclaim. She is the achiever of a nearly impossible feat, a female hero. She appears on the cover of the New York Times Magazine. She is a woman warrior. 3

The female warriors in the feminist sword-and-sorcery series ‘constitute a challenging, feminist encroachment upon a formerly male-dominated, limited popular literary form’. 4 These images of the emerging female hero—especially the complex urban woman—are present in the early UF tales by Emma Bull, Mercedes Lackey 5 and Charles de Lint. 6 This ‘new’ woman continues to dominate in later UF series.

The debate surrounding the role of the female protagonist is complex and at times quite negative because often the role of the hero is ignored by the debate over gender. A hero exists in and represents the cultural order that created him or her. The role should question, inspire and challenge, but is not utopic in quality. Fantasy is an amalgamation of past, present and future images used to help readers evaluate the current era. 7 Thus, the female protagonists of fantasy will always partly represent the expectations and limitations of the culture that produced them. The fantasy society derived from contemporary society is still, like other historical societies, a patriarchy. This influences any perception of culture because, according to Joanna Ross, patriarchies ‘imagine or picture themselves from the male point of view’. 8

A female hero runs the risk of sacrificing either masculine or feminine qualities—she may need to reject either traditional gender roles or new-age gender roles,[2] and must either accept a partner or remain alone. Regardless of the choice, the protagonist will be met with criticism from some faction. Even the ‘earth mother’ hero comes under fire as perpetrating gender stereotypes by women who have rejected this role. The problem is that there does not exist a single representational view of women, even in the form of an accepted archetype. I argue that the underlying issue is that contemporary gender roles are still evolving and no single character can capture this.

The female hero’s inner conflict

A characteristic of the UF female hero is the sense of inner conflict that reflects the issue of unclear gender roles in contemporary society. Sensitive to the challenging role they are forced into as women and heroes, the characters are often presented as deeply conflicted individuals. Gay’s protagonist Charlie is deeply troubled by the changes in her life that have thrust her into the role of hero. Charlie reflects that ‘[m]y mind, however, was filled with self-loathing and analysing. Hell, maybe I deserved to carry my burdens alone’. 9 She is further torn between the various demands on herself as a police officer, mother and hero. Charlie realises that, as a single mother, she should give up her job to offer a more secure future for her daughter. She also rejects the destiny her life is attempting to shape, as she works ‘to push all that good and evil shit aside and pull up my humanity’. 10 As a hero, Charlie is engaged in most of the novel in attempting to reject the call to adventure. Yet the very aspects of her life that Charlie rejects are the same that define her sense of self. She is a female trained officer (a contemporary woman warrior) and a mother. These two strongly gender-specific roles are at the center of her ability to be a hero. This is only one example of many that are present in UF. This is an area worthy of further consideration as the inner conflict, and to an extent the hero’s own sense of identity, is strongly influenced by their gender more than their role as a hero. An issue that continues to reflect the ambiguous nature of the perceived role of female heroes.

The fantasy hero

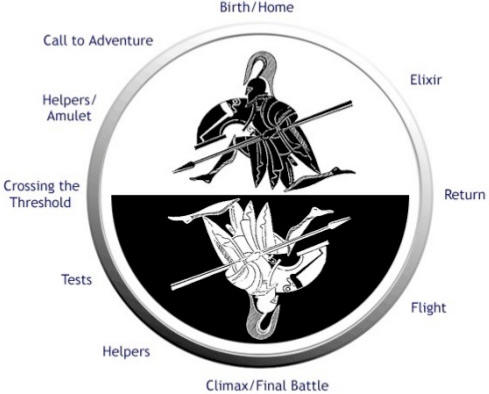

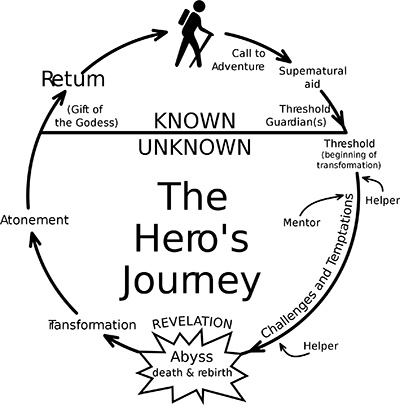

UF fundamentally belongs under the wider umbrella of fantasy; thus, it is necessary to examine the adaptation of the traditional hero before continuing with how the hero has been further transformed in the urban landscape of UFs. The hero lies at the core of any fantasy fiction, including UF. Traditional myths, folklores, fairy tales, epics and so forth centre on the journey of the hero: the heroic quest. These are taken at times from historical figures or the oldest mythologies because ‘the tales of heroic endeavours have been popular from time immemorial’. 11 Such influential narratives invite readers to ‘admire, emulate and/or measure themselves against the deed, attitudes and beliefs’ 12 of their heroes.

The traditional hero is more than a role model because, alongside his or her foil (the villain), the hero is the measuring stick for understanding the social complexities of the time in which tales are produced—with the hero representing the perceived correct choices and morality of the period, while the counter-character represents the immoral, antisocial and taboo aspects of society. Of course, this is a simplification of complex and deeply connotative tales. It is well documented and accepted that the role of the hero contains a deeper codex to understanding the period in which it is produced. As such, the hero is often an everyman—a representative type or culturally recognisable character who is able to represent ‘us’ on the journey. It is important that the heroes adopt conflicts, flaws and virtues that are shared by the reader. As such, the hero often becomes an archetype because the universal aspects of shared experience ‘take precedence over their individual personality traits’. 13

The archetypal hero adopts the relevant attitudes, beliefs and values important to the period. They are not perfect, but include a flaw relevant to the didactic resolution of their narrative. Their flaw and struggle to overcome it is matched against the foil of the villain, who encourages the flaw and attempts to weaken the hero’s resolve. The conflict of the tale often reflects the particular conflicts present in a social group. The outcome of the hero’s journey may reinforce, reject or question the principles of a social group. 14 As such, the qualities of a hero vary greatly in traditional tales, from humility to arrogance, or from humble origins to great physical or magical prowess. Heroes are endowed with a uniqueness that allows them to stand apart and complete a grand quest.

The contemporary fantasy novel has developed from these roots and continues to serve the same purpose. A hero is still expected to fulfill this traditional journey. Although the exact nature of the experiences and stages in the journey may have changed from Joseph Campbell’s 15 examination of traditional myths, the core remains. It requires a hero representative of the yearnings and desires of the day to set out on a transformative journey. The echoes of traditional heroes remain closest to their original form in the epic or Tolkienian fantasy stories[3] from which UF deviates. Yet, regardless of the thematic or even generic changes, the hero’s journey remains a vital element of any fantasy narrative.

The characteristics that define a hero vary between the context of a narrative’s production and the overall didactic resolution of the narrative. In UF, heroes tend to be driven by three motivations: a sense of moral responsibility, the desire to act, and a willingness for self-sacrifice. Individually, these characteristics are already present in society. However, combined, they are the makings of a hero, and too often the last two are absent in contemporary society—especially in cities. UF author Laurell K. Hamilton’s Anita, from her series Anita Blake: Vampire Hunter, 16 is an example of this because, unlike most UF protagonists, she is not motivated by danger to her own family or friends. Instead, usually in the parameters of her job, Anita becomes aware of a threat that needs to be contained or resolved, simply because it is the ethically right thing to do, regardless of the risk to herself. An example of this is the following discussion between Anita and another character in The Laughing Corpse:

‘I have no personal stake in these people, Jean-Claude, but they are people. Good, bad, or indifferent, they are alive, and no one has the right to just arbitrarily snuff them out.’

‘So it is the sanctity of life you cling to?’

I nodded. ‘That and the fact that every human being is special. Every death is a loss of something precious and irreplaceable’. 17

Hamilton provided her protagonist with a deep moral code that guides her decisions, stating simply that ‘[y]ou gotta be able to look at yourself in the mirror’. 18 What makes these UF protagonists heroes is the fact that they are motivated beyond their own personal safety and wellbeing. Patricia Briggs’s protagonist Mercy throws herself in front of a projectile to save another, and later alone hunts down a dangerous vampire. Kelly Gay’s hero Charlie offers up her own life willingly to save others, as does Suzanne McLeod’s Genny. In addition, novel after novel, Hamilton sends her hero into every dangerous, horrifying situation imaginable to risk her own life in an effort to continue keeping St Louis safe. The motivations and actions of UF heroes are inspiring, yet are merely continuing to draw on the tropes of older mythos.

The role of the hero is to act as a reflection of the concerns and conflicts of his or her period. In many ways, I argue that the mass-produced heroes perfectly reflect the commercialisation of mythology in our contemporary world. The hero is an evolving character and it is necessary to understand that such a process also reflects the changing ideas of different times. One of the most significant shifts in the construction of the hero, during the same period of criticism, is the development of the female hero. The traditional hero in epic fantasy has been predominantly male, which, as Grixti stated, is unsurprising because, ‘given the patently patriarchal and phallocentric orientations traditionally endorsed by such tales, for a long time heroic fantasies of this broad type were very much an exclusively male-dominated area’. 19 This is understandable since much of literature and history endorses this view. Indeed, still today, there is contention over the right of women to fight in the military in Western society. 20 If women are denied the right to participate in real heroic roles, it is unsurprising that fantasy continues to favour male heroes. Although the masculine hero remains a staple of fantasy, there have been significant developments in the role of the female hero that continue in today’s UF.

The urban female hero

Ultimately, the UF female must fulfill the role of hero. She follows a fairly familiar version of Campbell’s hero’s journey and must meet the criteria expected of a hero engaged in heroic exploits. An archetypal hero is responsible for saving their world from a villain and must display an ability to transcend temptation. 21 The UF hero performs these functions by resolving the antagonist, securing the safety of their city and overcoming an internal flaw in the process. UF is still primarily a fantasy subgenre; thus, the elements of a fantastic journey are present. The hero is expected to face a threat of a proportionate level, or ‘evil’, on equal ground. 22 It is vital that the hero is changed by this experience and sacrifices something significant to ensure success. The UF hero meets all these requirements to be considered a heroic archetype. However, the hero is further distinguished by their gender. As a female, the UF hero offers an opportunity to examine the characteristics of a hero. As Grixti stated, ‘the depiction of women in roles demonstrating strength, initiative, independence and wisdom (the ingredients of the heroic life) constitutes a critical reclaiming of the concept of heroism out of the patriarchal rut into which it had been lodged’. 23 The UF female hero adopts the opportunities of her urban world to help fulfil her heroic journey. A complex melding of heroic archetype and urban woman forms the UF hero. Yet it is notable that the construction of a female protagonist, let alone a hero, has been a struggle in fantasy fiction.

Fantasy fiction’s flexible boundaries offer female (and sometimes male) authors a space to experiment with the female hero. One of the first notable changes was what is best considered the ‘shero’—a female hero with all the same characteristics, concerns and motivations of a male hero. The shero is a hero with a female body and predominantly masculine traits. Simply put, heroic masculine attributes were added to desirable female bodies. As Elizabeth Wulf stated, this resulted in the creation of a ‘new breed of female hero without challenging the existing model of heroism or upsetting the gender balance’. 24 These female heroes, such as Red Sonya,[4] were savage fighters with a hero’s strength, but were also overly sexualised and often skimpily clad. In epic and sword-and-sorcery fantasy there appeared female heroes who would ‘play conventional male roles as warriors’. 25 These female heroes would fulfill the masculine hero role in the story, accompanied by the fulfillment of traditional quests. However, their personal behaviour and motivations often reflected what was considered more feminine resolutions. As Charlotte Spivack stated:

Their [male heroes’] emphasis is on physical strength, courage and aggressive behaviour. In the fantasy novels the female protagonists also demonstrate physical courage and resourcefulness, but they are not committed to male goals. Whether warriors or wizards, and there are both, their aim is not power or domination, but rather self-fulfilment and protection of the community. 26

Such heroes are seen in the works of authors Ursula Le Guin, Anne McCaffrey, C. L. Moore and Margaret Weiss. However, these types of heroes have remained in the minority in high fantasy because readers continue to show a preference for either alternative versions of the traditional masculine hero or the attractively sexualised female hero. These types of female heroes are accepted in popular culture ‘because they embrace masculine acts of heroism combined with desirable forms of femininity’. 27

The UF hero came into being at the same time that many other fantasy authors were developing female protagonists. In the same manner that UF arose as a response to the overabundance of high fantasy fiction available, the UF female can be assumed to have developed as a response to an excess of male heroes. Emma Bull and Mercedes Lackey laid the groundwork in the late 1980s with their characters Eddi McCandry and Diana Tregarde, respectively—choosing to develop female protagonists who were heroes in their urban setting. Charles de Lint also introduced Jilly Coppercorn—an artist, impromptu social worker and diplomat to the supernatural—in his first Newford short story collection. These three authors had the greatest effect on developing the foundation characteristics of the UF hero. Following these were a plethora of authors who have further developed and polished the UF protagonist, such as Laurell K. Hamilton, Patricia Briggs 28 and Kelly Gay. This evolution has developed a female hero with a number of distinct characteristics unique to UF; an evolution that continues as each new voice adds to the complexity of this modern-day hero, resonating with female readers world-wide.

Notes

- There are exceptions of course, such as the works of Charles de Lint, China Mieville, Jim Butcher and M. L. Brennan, to mention a notable few, in which there are male authors and/or male protagonists.

- I use this term loosely to refer to the dichotomous view of the career woman, lesbian, earth mother, and so forth that can be located on the continuum opposite to the traditional mother and wife figure.

- Examples of such traditional masculine heroes are present in the works of George R. R. Martin, whose works have exploded in popularity due to the television adaptation of his series A Song of Ice and Fire. Authors such as Robert Jordan and Robbin Hobb have also continued writing in the high fantasy, fairly traditional masculine hero form from the early 1980s to today.

- Red Sonya is a character developed by Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith that appeared in Marvel Comics. Depicted as a muscular and extremely sexualised redhead, she wears a bra and loin cloth made from chainmail, an obviously highly impractical and absurd costume for a warrior. After being raped at a young age, she is gifted by a goddess with incredible fighting skills upon the condition that she will never lie with a man unless he defeats her in combat—a premise that is already disturbing and hopefully not particularly aspirational for young women.

Works Cited

- Bull, E. (2001). War for the oaks. New York, NY: Orb. ↩

- Barr, M. S. (1987). Alien to femininity: Speculative fiction and feminist theory. New York, NY: Greenwood Press. p. ix. ↩

- Barr, M. S. (1987). Alien to femininity: Speculative fiction and feminist theory. New York, NY: Greenwood Press. p. 83. ↩

- Barr, M. S. (1987). Alien to femininity: Speculative fiction and feminist theory. New York, NY: Greenwood Press. p. 85. ↩

- Lackey, M. (2005). Burning water. New York, NY: Tor. ↩

- de Lint, C. (1993). Dreams underfoot. New York, NY: Orb. ↩

- Elkins, C. (1985). An approach to the social functions of science fiction and fantasy. In R. A. Collins & H. D. Pearce (Eds.), The scope of the fantastic—Culture, biography, themes, children’s literature: Selected essays from the First International Conference on the Fantastic in Literature and Film (Vol. 2, pp. 23–31). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 24 ↩

- Ross, J. (1973). What can a heroine do? Or why women can’t write. In S. Koppelman Cornillon (Ed.), Images of women in fiction: Feminist perspectives. Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press. p. 4. ↩

- Gay, K. (2009). The better part of darkness. New York, NY: Pocket Books. pp. 145–146 ↩

- Gay, K. (2009). The better part of darkness. New York, NY: Pocket Books., p. 75 ↩

- Grixti, J. (1994). Consumed identities: Heroic fantasies and the trivialisation of selfhood. Journal of Popular Culture, 28(3), 207. ↩

- Grixti, J. (1994). Consumed identities: Heroic fantasies and the trivialisation of selfhood. Journal of Popular Culture, 28(3), 214. ↩

- Tymn, M., Zahorski, K. J., & Boyer, R. H. (1979). Fantasy literature: A core collection and reference guide. New York, NY: R.R. Bawker Company.p. 8. ↩

- Elkins, C. (1985). An approach to the social functions of science fiction and fantasy. In R. A. Collins & H. D. Pearce (Eds.), The scope of the fantastic—Culture, biography, themes, children’s literature: Selected essays from the First International Conference on the Fantastic in Literature and Film (Vol. 2, pp. 23–31). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 24. ↩

- Campbell, J. (1973). The hero with a thousand faces. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ↩

- Hamilton, L. K. (2009). The laughing corpse. London, England: Headline Publishing. ↩

- Hamilton, L. K. (2009). The laughing corpse. London, England: Headline Publishing. p. 221. ↩

- Hamilton, L. K. (2009). The laughing corpse. London, England: Headline Publishing. p. 175. ↩

- Grixti, J. (1994). Consumed identities: Heroic fantasies and the trivialisation of selfhood. Journal of Popular Culture, 28(3), 208. ↩

- Buttsworth, S. (2002). ‘Bite me’: Buffy and the penetration of the gendered warrior-hero. Continuum, 16(2), 185–199. doi:10.1080/10304310220138750 ↩

- Ramaswamy, S. (2014). Archetypes in fantasy fiction: A study of J. R. R. Tolkien and J. K. Rowling. Language In India, 14, 621. ↩

- Waggoner, D. (1978). The hills of faraway: A guide to fantasy. New York, NY: Atheneum. p. 12. ↩

- Grixti, J. (1994). Consumed identities: Heroic fantasies and the trivialisation of selfhood. Journal of Popular Culture, 28(3), 209. ↩

- Wulf, E. (2005). Becoming heroic: Alternative female heroes in Suzy McKee Charnas’ The Conquer’s Child. Extrapolation, 46(1), 120-132. Retrieved from www.proquest.com. p. 122. ↩

- Spivack, C. (1987). Merlin’s daughters: Contemporary women writers of fantasy. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 8. ↩

- Spivack, C. (1987). Merlin’s daughters: Contemporary women writers of fantasy. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 8. ↩

- Wulf, E. (2005). Becoming heroic: Alternative female heroes in Suzy McKee Charnas’ The Conquer’s Child. Extrapolation, 46(1), 120-132. Retrieved from www.proquest.com. p. 120 ↩

- Briggs, P. (2009). Iron Kissed. London, England: Orbit. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Blasting post! Happy to see strong female characters.

Michone from The Walking Dead. I haven’t read the graphic novels but on the show she is the baddest of asses but maintains some femininity. She is a mother figure and in the later seasons shows emotional depth beyond katana wielding zombie slayer.

I love urban fantasy. I love the idea that the normal one and the supernatural one exist just a hair away from one another.

I recommend Elise Kavanagh by SM Reine! She is very tough and brave and smart, yet human, with many flaws. Her character annoys the hell out of me and makes me love her at the same time.

I recommend another book with a kick ass female lead. It is Voodoo Moon by June Stevens Westerfield. Like Fiona from Voodoo Moon, all of the females from the list can rule the world on their own, no man needed. They do find love. It’s not because they need to by society’s standards but because they want too. I think that is why we love the books so much.

Here are few with strong females-

Cassie Palmer series by Karen Chance, The Weird Girls by Cecy Robeson, Alex Conner Chronicles by Parker Sinclair, Allison Besckstrom series by Devon Monk, Alex Craft series by Kalayna Price, and lots of strong women in Kelley Armstrongs the Otherworld series.

Recommend The fever series by Karen Marie Moning. It’s got everything!The only complaint you will have about this series is your lack of motivation to do anything but read. Darkfever is the first book.

Kickass females are important in fiction. The time of the damsel in distress awaiting rescue is over!

A well written and well argued position that might help explain the problem to those who fail to see the importance of representation in the arts.

I’m a huge fan of Kelley Armstrong. Bitten was the first and she has added many strong females into most of her books.

Im looking for a book i once haf with a fab sassy kickass woman who life purpose is to kill demons and shifters that cause havoc. Shes half witch and shifter amd has 12 specific tattoos that if she has them then everyone knows that thats the life she has to lead including a cektic design tattoo that heals….she has white hair….and officially becomes the mate to an alpha werewolf…..

Anyone know which book im talking about?

Ive forgotten the name but it got deleted from my phone and have been looking everywhere for it.

I think this genre, besides romance, is the only one dominated mostly by women.

Great post! You’ve piqued my interest in all these–I do so love strong heroines, and special powers don’t hurt either.

I can’t think of a heroine who ‘comes into her girl power’ – but I’m a devote of heroines who have strength, wisdom and courage. I’m particularly fond of Xhex in Lover Mine; one powerful heroine. Eve Dallas is also a heroine who is ‘all that and more’. I think with these two heroines, it’s not so much that they come into their power – it’s that they are powerful women who finally allow other emotions/traits to become part of their power.

War for the Oaks is urban fantasy with a female protagonist who is neither stupid nor helpless and isn’t too special (she’s a talented musician but that’s it). From what I remember she was a no nonsense, take-charge kind of person, definitely not an airhead.

What a great article!

Pretty much 80% of Terry Pratchett’s female characters…

Any queer warrior suggestions?

If you count asexual, then Elizabeth Moon’s Deed of Paksenarrion. Also Mercedes Lackey’s Tarma and Kethry short stories.

The Thousand Names by Django Wexler.

Amelia Faulkner’s books include demisexual, aromantic, bisexual, pansexual, lesbian, and other queer orientations.

It seems to me that there’s 2 kinds of Urban fantasy. One has wizards and cops or cops that are wizards, and is about equally written by men and women.

The other has girls falling in love with vampires, werewolves, ghosts, whatever else crawled out of the Nevernever, and is mostly written by women.

The second type there is, from a marketing perspective, more accurately described as Paranormal Romance, shelved as a part of the Romance section, a category thoroughly dominated by female authors (and some men using pseudonyms).

You forgot orphan/adopted girls finding out that their biological family is actually an ancient, royal line of Nevernever creatures and, as the sole remaining member of the family (having had this revealed to them by the previous last member while on their death bed), it’s now up to them to be their new champion while, of course, still falling in love and making whoopee with the Nevernevers.

For good female leads I always recommend the Kate Daniels series from Ilona Andrews. A very tough no nonsense female protagonist. She does charge into dens of demons yes, but because she can wipe her boots with them. The series has excellent action, snarky humour and some real emotion. Also it gets better with each book. Also ignore the covers.

Fantasy has stereotypically been a male dominated genre.

It’s cool if heroines are distinctive and powerful.

Under some circumstances, important female leaders have to behave like “villain” to hold and keep power. Elizabeth I of England famously said that she had the frail body of a woman, but the heart of a prince.

Heroines are defined in a narrow lens, which is why so many women are drawn to the uncompromising power of the villainous alternative.

I never comment on anything EVER, but you, my QUEEN, need to know that this is EVERYTHING. Thank you for this.

I’m an urban fantasy consumer and approve of this article. Good job!

If we’re to link this topic to the anime medium, I suggest Psycho-Pass, it’s a great watch.

Two of my fave kick ass heroines are Elena, the Guild Hunter turned Made Angel from Nalini Singh’s Angel series and Lt. Eve Dallas from JD Robb’s In Death series of books.

I never realized UF was predominantly female-centric!

It seems that some genres like Urban Fantasy, Dark Fantasy, Paranormal… are filled with amazing female protagonists.

In the comics medium, my favorites are Velvet Templeton (Velvet), Forever Carlyle (Lazarus), Wonder Woman, Natasha Romanoff (Black Widow), Kamala Kahn (Ms. Marvel), Carol Danvers (Captain Marvel)….

A lovely, thorough analysis of the ever-changing female hero. What I like about this ever-changing character is that we’ve come far–females have improved by leaps and bounds in the urban hero/fantasy narratives. But there is always room for improvement, so creators can always work to get better. There will never be a “perfect” hero who satisfies everyone, but that doesn’t mean we can’t create the best heroes our minds will bestow on us.

Dangerously Wicked is a fun read with a kickass female protagonist. Based of the Baba Yaga myths. Yes there is romance, but the tough chick who protects children and can face any crazy scary magic, is worth a read.

Great Article! Never really delved into the UF but reading has piqued my interest and I may give it a whirl. I’m a feminist science fiction fan so anything by Ursula K. Le Guin is a must and Margret Atwood’s moral mirror of dystopia is always great reading.

UF has fast become my favourite genre of all time, closely followed by the fast growing in popularity genre of RH (Reverse Harem). Two of my favourite UF authors are up and coming authors, McKenzie Hunter and Linsey Hall. Both have woven incredible worlds in which to get lost in and have created leading characters that are not only deep, but develop and change throughout their series.

wonder women? no , don’t have?

In a sense the second wave mentioned in the article has very much declined since its peak in the 80s and 90s.