Warner Bros. and the Infamous Censored Eleven

Disclaimer: This article contains material which could easily been seen as offensive… because said material is pretty offensive, but it’s material from another era and interesting from a historical perspective. I apologise if anyone is upset by the images and content featured below, they are pretty unpleasant.

Cartoon characters, they’re an adorable bunch, right? Picture them, with all their bright colours and big eyes, singing merry melodies and going on exciting capers, like Toon Town from Who Framed Roger Rabbit? Nothing could be more charming, innocent and inoffensive than a wholesome cartoon creature. Sure, there are some bad seeds, like Fritz the Cat (and pretty much anything else Robert Crumb ever came up with), and adult cartoons like Archer and South Park, but otherwise cartoons are fun for all the family, right?

Cartoon characters, they’re an adorable bunch, right? Picture them, with all their bright colours and big eyes, singing merry melodies and going on exciting capers, like Toon Town from Who Framed Roger Rabbit? Nothing could be more charming, innocent and inoffensive than a wholesome cartoon creature. Sure, there are some bad seeds, like Fritz the Cat (and pretty much anything else Robert Crumb ever came up with), and adult cartoons like Archer and South Park, but otherwise cartoons are fun for all the family, right?

Well, as it turns out, maybe not. If you look back into the murky past of animation, you’ll find something more than a little disturbing, like discovering Nazi memorabilia in your beloved grandfather’s basement: animation used to be really, really racist. Like, Michael Richards’ stand-up level racist. So racist that, even if I tried to describe it, it wouldn’t really do it justice. What’s worse is that a lot of the horrible things being said and done are being said and done by beloved characters like Bugs Bunny.

Yes, it’s true, far from being the cute, cuddly benign figures of our childhoods, cartoons have a dark, unpleasant, racist past. Of course, most, if not all, of these cartoons have not been shown on TV during my lifetime, and most are subject to deservedly heavy censorship by, not only the authorities, but the companies that own them. You know that something has to be pretty inflammatory when the people who own it withhold it from public consumption for fear of causing offence.

The best and most well-known example of this kind of restraint has to be the infamous (and titular) Censored Eleven, eleven cartoons withheld from distribution and syndication by United Artists in 1968. Since that time, they have never been released on VHS, but have been screened at select animation festivals. They can also be readily found on YouTube, although, be warned, they do contain some pretty nasty material.

The earliest of the eleven shorts is Hittin’ the Trail for Happy Land, a lively piece mostly set on-board a steamship. Made over 80 years ago, in 1931, the animation could be best described as of its time, with heavily exaggerated motions, limited lip-synching, and black and white cartoon animals smiling while they play musical instruments. Of the eleven, it is probably the least objectionable, because the oblique references to “Uncle Tom” are directed at a cartoon dog with very few stereotypical features.

When the cartoons graduated to colour, however, the offensiveness sky-rocketed. Sunday Go to Meetin’ Time was made five years later in 1936 and is the second oldest of the Censored Eleven. It features one of the things that later became a hallmark of this particular sub-genre of animation, portraying African Americans as having lips so large and pale that, in some cases, they look more like beaks. Clearly, these portrayals were influenced by blackface and minstrel shows. It also features extensive use of pidgin English, but, for all of its faults, it is still not even nearly the most offensive of the bunch.

When the cartoons graduated to colour, however, the offensiveness sky-rocketed. Sunday Go to Meetin’ Time was made five years later in 1936 and is the second oldest of the Censored Eleven. It features one of the things that later became a hallmark of this particular sub-genre of animation, portraying African Americans as having lips so large and pale that, in some cases, they look more like beaks. Clearly, these portrayals were influenced by blackface and minstrel shows. It also features extensive use of pidgin English, but, for all of its faults, it is still not even nearly the most offensive of the bunch.

In terms of the worst of the bunch, it’s a tie between three or four of the later cartoons, including the similarly themed The Isle of Pingo Pongo and Jungle Jitters, both of which revolve around extremely troubling portrayals of native Africans. In the former, they engage in cannibalism (of sorts) and, in the latter, they seem to only dance around playing jazz music. In both, the populations are shown as being dim-witted, lazy and are, again, drawn in the same stereotypical fashion (with Pingo Pongo being a particularly obscene example) to the point that they barely seem human.

The ones that stick in the mind most, though, are the two contributions from Bob Clampett, Tin Pan Alley Cats and the unfortunately titled Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarves. It’s a shame that they’re so racist, really, because these two are actually pretty good in a lot of ways: they feature some excellent animation and great jazz scores. Unfortunately, they also rely the exact same stereotypes as the previously mentioned animations.

Easily the worst of the two is Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarves (the name does give it away a bit), which features on particularly unsavoury joke about a kill squad that charges for everyone else, but kills “Japs” for free. Yep, you read that correctly. The rest of the content is similarly distasteful, with every character being one grotesque caricature or another, beginning with a dancing scat-man with a gold tooth. As with the others, it is easy to see how offensive the short is, but the creator, Bob Clampett, might not be so easy to pigeonhole.

Easily the worst of the two is Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarves (the name does give it away a bit), which features on particularly unsavoury joke about a kill squad that charges for everyone else, but kills “Japs” for free. Yep, you read that correctly. The rest of the content is similarly distasteful, with every character being one grotesque caricature or another, beginning with a dancing scat-man with a gold tooth. As with the others, it is easy to see how offensive the short is, but the creator, Bob Clampett, might not be so easy to pigeonhole.

Coal Black came about when Clampett was approached by the cast of an all-black musical, with whom he collaborated closely in the creation of the piece. By his own account, the whole process was respectful and done with mutual admiration after they specifically requested that a cartoon be made featuring black characters. Now, the veracity of these claims cannot really be assessed here by me, but they do raise an interesting point. How much of these cartoons is deliberate and malicious racism, and how much is simply the result of the time in which they were produced?

Don’t get me wrong, clearly the content in these shorts in unacceptable, but how much can be forgiven of the creators and, more to the point, how much can we look past their dubious content to see the artistic merit within? Bob Clampett, so I have heard, was inspired to make these shorts by hanging out at black clubs and soaking up the jazz music. You can tell by the way he directs the shorts that he has genuine affection for the music included. Unlike some of the other pieces, which can be seen as purely malicious, the Clampett pieces can be redeemed. Similarly, Clampett himself can be understood as something other than massively racist.

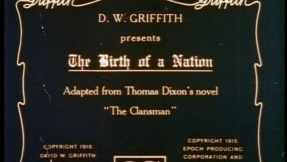

The analogy, from an artistic side, would be the D. W. Griffith classic Birth of a Nation, which features the uneasy pairing of technical and narrative mastery, with horrible, horrible racism. It is widely accepted that Birth of a Nation is an extremely important piece of cinema, despite its more troubling content, and is regarded as one of the best films ever made. The same is often said of Coal Black, but the issue of whether art can be redeemed despite racist, or other offensive, content remains.

The analogy, from an artistic side, would be the D. W. Griffith classic Birth of a Nation, which features the uneasy pairing of technical and narrative mastery, with horrible, horrible racism. It is widely accepted that Birth of a Nation is an extremely important piece of cinema, despite its more troubling content, and is regarded as one of the best films ever made. The same is often said of Coal Black, but the issue of whether art can be redeemed despite racist, or other offensive, content remains.

There’s another trend that I noticed when you look at the banned cartoons and other cartoons from the era. Those that have escaped censorship almost invariably feature anthropomorphised talking animals singing, dancing and generally having a merry old time. The banned cartoons have the same essential structure and premise on the whole, with one key ingredient altered: in the place of animals, you have black folks. In that time period, black people, it would seem, were seen as little more than animals that could talk (in animation at least). Now, I think that’s a dozen times worse than the offensive drawings or the speech patterns. It’s the way that they were employed in the same way as a talking dog that is the truly disturbing part of all this.

In any case, it would seem that Coal Black was at least made without malice at the heart of its creator’s intent. It is simply an unfortunate throwback to a time when that was simply how you drew black people in cartoons. Others, like some of the ones I mentioned, are far worse. Some are downright horrendous. The worst I can think of is not part of the censored eleven, and was made during World War 2 as a piece of propaganda. Its name is Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips.

That’s right, Nips the Nips. With a title like that, there can be no mistaking the intent behind it. This little charmer features one of the most virulently offensive portrayals of an Asian I have ever seen. Think Mickey Rooney in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, then turn it up to eleven. I’m talking buck-teeth, slanty-eyes and constant, unintillegible, vaguely Asian-sounding yammering. Really, it’s quite repulsive, but it gets worse when (spoiler alert) Bugs Bunny tricks the Japanese into eating grenades and blowing themselves up. Yep, this is a cartoon where Bugs Bunny teaches kids that it’s fun to kill Japanese people.

That’s right, Nips the Nips. With a title like that, there can be no mistaking the intent behind it. This little charmer features one of the most virulently offensive portrayals of an Asian I have ever seen. Think Mickey Rooney in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, then turn it up to eleven. I’m talking buck-teeth, slanty-eyes and constant, unintillegible, vaguely Asian-sounding yammering. Really, it’s quite repulsive, but it gets worse when (spoiler alert) Bugs Bunny tricks the Japanese into eating grenades and blowing themselves up. Yep, this is a cartoon where Bugs Bunny teaches kids that it’s fun to kill Japanese people.

I find these cartoons interesting. It isn’t because I have any racist inclinations myself, or look at them and laugh. They’re just fascinating as historical documents. You look at them and you get a window into a very different time and place, and you realise that, while the world as it exists today is far from perfect, it’s one hell of a lot better than it was back then. You only need look at the reaction to the “film” The Innocence of Muslims to see how different things are. There is a case to be made that pieces like these should be included in school curricula on the subject of the history of race relations, simply to demonstrate what used to be acceptable, provided, of course, that they were shown in the correct context. At the very least, they are a disturbing document of the one of the ways in which we used to dehumanise and denigrate our fellow human beings.

They also raise the issue of how best to evaluate the creators of this kind of work. Are they genuinely and actively despicable, or is it down entirely to the time in which they lived? I’ve already written about Bob Clampett working closely with the all-black cast who more or less commissioned Coal Black. Can he honestly be said to have been a racist on the strength of the work, or is it just unfortunate that what was seen as acceptable, or even cool, then is considered unacceptable now? This debate can be applied to any number of pieces, like the works of Leni Riefenstahl, and won’t be solved. If I, however, had to come to some manner of conclusion on the issue, I’d say that such people can be forgiven for transgressions induced by the standards of the time, and that these works can be appreciated from a technical and artistic standpoint, even if you have to ignore the more unsavoury aspects.

Of course, most of these ancient and censored cartoons have no such merit, and should probably just be avoided.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs is the best one IMO. I have only one gripe about this cartoon (which has nothing to do with the racial stereotyping). It seems to run very quickly — even more so than most Avery/Clampett cartoons of the era — and tends to become disjoint at points. This is probably due to the fact that Bob Clampett wanted to make this a two-reeler (~13 minutes), but producer Leon Schlesinger was totally against the idea of an animated film going beyond one reel (possibly some anti-Disney sentiment?)

I meant worse in terms of racism. I agree that its the better of the two Clampett shorts.

I firmly believe that these cartoons should be made readily available to art historians, war historians, sociologists, musicians, and aspiring animators.

It still holds great value to all of those fields to this day.

Outstanding article. Nips the Nips was on the original vol 1 of the laser disc collections when MGM had the rights, but was recalled and re issued without that short.

There have been rumors of the 11 being released through the Warner archive for a few years but nothing has happened yet.

While I am sympathetic to the racial concerns, from a historical and animation perspective, there is NO reason these shouldnt be available to anyone that wants them.

After all, the DVD and Blu-ray sets have the disclaimer in them about sensitive material, and that states they are intended for the adult collector. If they would just let the buyer make the informed choice, I imagine these would sell quite well

Bet WB is trying to shove this under the carpet 😉

Nope, they’ve released collections and have openly admitted to their historical merit.

Great article. I’m not 100% certain I agree with you on forgiving the racism of some of these cartoons because their creators had their hearts in the right place, or because they didn’t know any better. Casual racism is just as damaging as outright bigotry – sometimes even more so, because it means that we excuse it or try to understand it.

I could’ve sworn that I saw some of these in film school, off of some DVDs that Warner Brothers deliberately released as a field for study. They seem a bit more willing to acknowledge that they actually made the cartoons – unlike Disney, who seem hell-bent on denying they were ever racists.

Great article and I agree with mostly everything you say. To me, the best art is art that challenges us, even if these cartoons (or The Birth of a Nation, a great example you used) challenge us in ways that we wouldn’t like. That is, they challenge us to open our minds and embrace those we don’t agree with. I don’t agree with the racist content of these cartoons, but they are important and they are works of art, and they should be preserved as such.

While I haven’t seen any of the shorts mentioned here, I have watched a number of Disney and bugs bunny shorts meant to act as war time propaganda. As others have mentioned, I think it’s important to keep these works around, not only so we can study and appreciate the technical aspects of how the animation works as an art form, but also as a way of remembering where we have come from and the role even seemingly innocent cultural works play in influencing society. Also, while I don’t completely agree that Bob Clampett should be forgiven for accidental racism, I think the subject of malicious, purposeful racism vs. casual racism that you’ve touched on is important to discuss as it’s still such a prevalent issue in many works today.

Bugs Bunny got what he deserved on Family Guy when Elmer killed him the way he did, I couldn’t have done it better myself.

I’d be interested to see a follow-up to this on casual racism from more recent UA/WB productions – or a companion piece on Disney’s more remarkably racially offensive animated works. A friend convinced me to watch “Dumbo” recently (as an adult) and I found myself actually shocked, not at the all-too-banal realization that the racism of that time recorded into contemporary entertainment, but that the film, so thoroughly racially divisive that it actually features the character Jim Crow, continues to entertain many American children today.

Bugs Bunny a racist? Shame on you Warner Bros

Interesting article. The episodes almost act as a window in to the ideologies of society in that point in time.

I hate to seem condescending but this article seems very child-like in nature. It handles these animations with such kid gloves it really robs it of any weight to me. It has inkling’s of stating an opinion but then immediately retreats from other points. The disclaimer does it a disservice because it implies that it will be more than just “This stuff was racist and that’s bad” which is how the article reads, at least to me.

Even if characters like Bugs Bunny have a more common “family friendly” association by contemporary standards, when the original characters were made the target audience was for adults. With that in mind, segregation of races was still legal and widespread until the mid-1950s. Adult audiences and racism tend to go hand-in-hand. Present day is no exception with Archer, South Park, and Family Guy being 3 of the most popular adult cartoons and all of which poke fun at various races.

This is fascinating! Although I always felt a slight undercurrent of racism in the old comics (e.g., when Daffy Duck would break into a tribal-looking dance and say Bwanah Memsahib), but I never would have known that it went so far!

This is fascinating! Although I knew there was a slight undercurrent of racism (e.g., Daffy Duck saying Yasser, Yasser, Massuh) but I never would have known that it was this permeating!

There are two overwhelming problems with your underlying premise:

1 – All people were made into caricatures in the cartoons of that time, both in terms of physical features and behaviors. It’s no more or less offensive to do that to non-Whites than to Whites.

2 – Many of the cartoons cited were wartime productions. There’s nothing particularly offensive about lampooning and insulting the enemy in times of war or in preparation for an upcoming war. And, as in point 1, it was done to all our enemies and is no more or less offensive when it is the Japanese than it is when it’s the Germans and nobody is going to claim that lampooning the Germans in WW2 was offensive…because they were quintessentially White.

You’ve brought up a very very good point with the caricatures. That was a huge part to WB’s style, especially with celebrities. But where I disagree is that one can be offensive when lampooning the enemy. Not every single German was an enemy and the same goes for the Japanese (especially those in internment camps), yet the portrayals were exploiting the physical distinctions between these people. It was meant to degrade our perception of them on a physical level, not a political one (for the Japanese at least). The Germans were made fun of as Nazi’s because, I’m guessing, that was easier to recognize and exploit.

While I dont feel that —- was racist, that does not change the fact that the work in and of itself was. Coal Black was racist, even with the Black cast. I don’t know their reason for agreeing to do the project. Maybe they wanted to show off their music, and maybe because they, too, had seen how they were portrayed on television for a substancial amount of their lives, they did not see an issue with it. I don’t know, but that doesn’t change the content, not that you were saying that it does.

It’s really an interesting subject, honestly. These are historical cartoons, but these cartoons were on air and television…not too long ago, when you think about it. It kind of shows you exactly how “not over” the problem is.

Ah, I made a few errors when I submitted this because I hit the submit button too soon.

I was refering to Bob Clampett where the dashes are.

Also, I know that “on air” and “television” are the same thing, that was my mistake.

Lastly, I’m not quite sure about the forgiving tone you seem to be giving this “casual racism”. Casually being racist hurts us just as much as blatantly being so.

Very interesting. Disturbing. I’m now recalling other animal representations in classics… I watched Bambi not long ago and notice how camp Flower the skunk is, and how even HE can be twitterpated by a lady! Of its time, definitly!

The tone of this piece disturbs me not the racism itself. As a black animator I feel that these do need to be studied as process of art as a tone in history as a symptom to the disease.

If the process themselves were casually racist our looked at racism it would be different but as they are overt, the commentary should have been less accepting of the content or cold and fact driven. This is what happened this is why and done, not apologetic. I’m sure the designers of slave brands and had chambers have it their all as well, we don’t make excuses for them. No not when it is this overt.

I will say this though how will we be judged as history moves forward, what thoughts do we have now that will be considered backwards.

Bugs Bunny a racist, makes me reconsider the entire Space Jam film.

This article makes me want analyze the entire Space Jam more thoroughly. I’d add that Lazytown definitely rubbed me the wrong way growing up, as young African-American male.

Bugs Bunny was always chocked full of overt racism unfortunately.

I’ve looked at and studied all 11. The films are valuable for their historic examples of ethnic characterizations in pop culture. I wouldn’t show these to my kids, however, because they would see the films as entertainment instead of history. Nor would I market these films to “Kids” sections of DVDs at stores. The stereotypes make the films too adult.

It just goes to show you how far we’ve come as a country. It’s good to know the past, where we are coming from, the different zeitgeists of so many eras in American History. That in conjunction with observing the present can shed light on our direction in the future, which is good. But it’s also good to keep the past in the past. I have to admit, some of these are actually funny, even if blatantly offensive to a degree. I can even say that there is some morality and humor to some of the shorts.

You can see that some of the producers were really trying hard to not depict African Americans in general as deliberately bad and immoral on the whole. A form of entertainment cannot offer society a viewing experience beyond the scope of its current era. With that in mind, it is actually commendable the way some of these cartoons depicts African Americans and European Americans interactions with one another. (It’s difficult to keep in mind that these were meant to be entertainment for families. To do so, one nearly has to erase the divide between eras. But in doing so, one can see how the spirit of “family entertainment” is survived down to this day, and how there is a measure of stereotypes present in modern family mediums taken from the current era of society on which it is based, i.e. the empowerment of the child and dumbification of parents)

Considering the view of African Americans at the time of their production, it’s amazing that these even made it into production. But still, they are things I can understand being swept under the rug, which is good, too.

It’s good to see people willing to discuss the big picture and what it entails instead of focusing on the obvious little possible focal points to wring dry.

I personally think that the Censored Eleven should be released and distributed, uncut, but with a warning like what Warner Brother’s is doing right now to their older Tom and Jerry cartoons.

I find the same question of whether or not a creator can be separated from his work arises every time I read something by H.P. Lovecraft. By all accounts, Lovecraft was a racist among racists; he was terrified of what he considered “foreign” and it definitely is present in his work (the story “The Rats in the Walls” features an unfortunately-named cat whose racially-charged name has no bearing on the story whatsoever). However, despite this being an integral part of Lovecraft’s psyche, I honestly think this can be divorced from the work itself. I had read a great deal of his work before I read anything biographical, and besides instances like the aforementioned cat’s name which I chalked up to just being an unfortunate attitude of the times, I never had any inkling that his stories were anything more than terrifying stories for the sake of being terrifying. I can certainly see now what others have identified (or desperately tried to identify) as thinly-veiled racial hatred in horror trappings, but I think it goes too far to condemn the stories themselves as inherently racist based solely on the author’s shortcomings. There are people won’t even read the stories or engage in any contemporary media based on Lovecraftian themes, which I think is ridiculous. Any thinking person can separate an author from his work, just as “Coal Black”‘s unfortunate racial aspects can be separated from the perhaps well-meaningness of its creator.