Wenders and DeLillo: Images at the End of the World

Film has an uncanny persistence and life. In the work of German filmmaker Wim Wenders, there’s often a postmodern sense of self-consciousness of the medium. In many of the director’s films there are almost two movies at play: the narrative about characters, and the narrative about recording technology; meaning is derived from the way these may intersect. One would hesitate to call Wenders a true postmodern artist, though (if such a thing really exists). His feeling for the beauty of the everyday and his playful vision of humanity relish too much of moment to moment life. In individual scenes, his sense of wonder has little to do with the victimization by larger forces which characterizes pure postmodernism.

In this manner Wenders resembles another artist often characterized as postmodern, novelist Don DeLillo. This author’s self-prescribed task is more interesting, though maybe less difficult since less meta. Like Wenders, DeLillo does point to his own medium relatively often by discussing language and the power of the written word in apprehending reality. But he’s also a writer who frequently engages with a rival, a different medium and the most pervasive of the modern world: the image.

Film has an uncanny persistence and life. In Wenders’ Lisbon Story (1994), the protagonist finds that a mysterious Borgesian place you travel to with much difficulty, (Lisbon), is absent of the film director who invited you, and will undoubtedly be filled with everything else you need to make the movie. In The End of Violence (1997), a Hollywood producer in exile retains his pocket organizer to check emails (did this device even exist in 1997? Wenders would know). Wenders’ insistence on a once cutting-edge technology borders on sci-fi, similar to DeLillo, and makes for a weird kind of inevitable nostalgia (do wealthy technogogues fondly muse, ‘ah, yes, I remember that weird pocket television I had in 1991’?) This technology was so reaching when it was new that it barely had a life to begin with, but it has a new life in the films when viewed many years later. It lives in the character’s casual use of it. As with DeLillo, electronic products become enshrined as artifacts (sometimes instantly). The way that technology intersects with untouched landscapes gives a unique retro-futuristic meaning.

In this way Wenders acutely captures what feels like a ‘nostalgia of the present,’ a term believed to be first used by the Argentinian Borges in a poem of that title, musing: ‘Oh, what I would not give for the joy of being at your side in Iceland.’ If he’d been to the theaters in 1991, he could’ve done something akin to just that with the globe-hopping, insouciant Wenders epic, Until the End of the World (1991), where characters slip continents as easily as in the imagination (obtain the director’s cut, which at around five hours is either thinly masochistic or lusciously languid depending on your disposition). In the film, Europeans at the edge of nowhere (Australian outback) have better technology than exists anywhere else on earth: a machine with which to view your own dreams (albeit with grainy, high-contrast 90’s-type imaging). The trappings are old school, their purpose beyond our current means. Sidebar: it’s also a film which perhaps boasts the greatest film soundtrack ever compiled. Also worth noting is that in terms of structure, Wenders seemingly could not care less about plot, and DeLillo in that regard seems not far behind. Both artists’ works are typically suggestively folded tarps hung on only a couple hooks.

Film has an uncanny persistence and life. In DeLillo’s novel, The Names (1982), which takes place in Athens, an impossibly mysterious, murderous ‘numbers cult’ seriously considers being filmed. In the author’s most recent novella, Point Omega (2010), a former American defense specialist who has forsaken all to live in the desert hosts a young documentary filmmaker who wants to shoot an interview with him pertaining to his work: “Just a man and a wall…the man stands there and relates the complete experience…A simple headshot…One continuous take. Whatever you say, that’s the film, you’re the film” (DeLillo 21-22, 45). The filmmaker here maintains that film can cut through modern lies. In his special project it would be “where somebody stands and tells the truth” (45). For the older man, who has recently more or less opened his consciousness to the infinite and its accompanying sense of life’s finitude, the fact that he simultaneously entertains the possibility of this filmed deposition is uncanny. There always seems to be space for it. Indeed is there any illicit facet of the world that remains unfilmed? Film seems to attend the secret rather than miss it. Film is the secret, and the most open one at that. Technology has a weird abstract presence.

But where does film end?

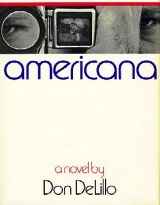

The documentarian’s dream interview of the defense specialist does not take place, leaving its potential for truth undetermined. In Until the End of the World, the heroine, Claire, falls into a narcissistic trance as she goes foetal in the Australian outback, quivering over a portable monitor displaying her own dreams. Eventually she has to cease succumbing to this inward mesmerism and proceed with finding her place in the universe. DeLillo’s work confronted film from the very start, and from the very start probed its limits. His debut novel, Americana (1971), is a yarn about a young businessman who sets out on a road trip across America to make a film. By the end, things descend into the diffuse, if not outright madness, the film becoming in the protagonist’s specialized language the “ultimate schizogram, an exercise in diametrics which attempts to unmake meaning” (DeLillo 347). DeLillo here could be touching on an aspect of film’s wordless montage, and how it may make suggestions beyond the limits of language. DeLillo deals with time, film, and memory in a way Wenders would too. A character in Americana muses to the protagonist: “You are looking at a newsreel of an earlier time. A man is standing in a room in America. It is you, David…What can the two of you say to each other? How can you empty out the intervening decades. It’s possible to put your hand to a movie screen and come away with a split second of light, say a taxicab turning a corner, and it’s right there on your thumb…You can talk to the screen and it may answer” (309). With this sense of an image’s palpability, its conjuring of time, we could nearly say the same about the alluring pastels of Until the End of the World, and a scene itself, wherein Claire, as pictured, clutches the screen of her own mind.

The companion piece to DeLillo’s Americana is another Wenders epic, Kings of the Road (1976), in which two laconic men, a drifter and a film projector repair man travel Germany fixing up the gear at different theaters. Worth noting: They have a portable 45 record player you slot records into like CD’s. The film ends with the drifter leaving a note for the repair man: everything must change. In the final scene, the repair man considers his future after conversing with an old woman who thinks a debased film medium is worse than none at all. He rips up his schedule and we understand he may be changing course, presumably to a place that may not follow the celluloid trail.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Wings of Desire is my all-time favorite German movie. It is also very high on the list of my favorite movies in general. I’ve not seen Paris, Texas but I went to the film museum in Berlin and Jim Jarmusch had handwritten a “thank you” note to Wenders for making it.

‘Wings of Desire’ and ‘Paris, Texas’ are amazing films, probably Wenders’ best, but they didn’t fit into the strand I was trying to locate in this article. That’s really interesting about Jarmusch. ‘Paris, Texas’ definitely feels like Wenders’ most Jarmusch-like film.

A good day never got in the way of delillo. But here we are future.

Don DeLillo is great. His underworld is great, but mao II is the one for me.

i’ve only read “white noise,” and it was pretty damned good. i’ve got a copy of “cosmopolis” i’m about to read, and i’ll tackle “underworld” soon. i would say pynchon is the best living author by far, with delillo and mccarthy being the next best americans, but then again i haven’t read “underworld.”

Yeah, ‘Mao II’ is really in the sweet spot for DeLillo, I’ve heard others say they also like it the best. ‘Underworld’ is extremely varied, and it never ceases to astonish me. There are so many quotable, memorable lines. It’s reverberations and meanings never end. I find it more truthful than ‘Gravity’s Rainbow'(though that’s a mind-bending opus).

White Noise was the book that got me into writing, but libra, mao 2, underworld…

White Noise is one of my favourite books, I’d love to make it into a movie.

I’d say Wim’s closely related to Nicholas Ray, or Yasujiro Ozu. Possibly Margueritte Von Trotta and Volker Schlondorf as well. But he really is a unique filmmaker and has a style all his own.

Wenders’ style isn’t easy to describe, seeing that it has changed over years. For instance films like “The American Friend” or “Paris, Texas”, “Buena Vista Social Club”, “The Million Dollar Hotel” or “Wings of Desire” don’t have a lot in common at first sight, at least they don’t when by style you mean his visual style first of all.

What relates all Wenders’ films in my opinion is his focus of interest, though: it is always the human condition he is interested in most, researching his characters in relation to their environment and circumstances, that’s also true when a film is about an ensemble rather than individuals, like in “Buena Vista Social Club”, “The Million Dollar Hotel” or “Wings of Desire”. In this respect I see him in the same humanist tradition as for instance Volker Schlöndorff, though their films look different (with perhaps the exception of Wenders “Paris, Texas” and Schlöndorff’s “Homo faber/The Voyager”, but maybe it was only me who felt some similarity here).

That’s a great point. His style has daringly changed and he should get more credit for it. It’s hard to imagine how the same person who made ‘Wings of Desire’ also made ‘Paris, Texas.’ It’s also great that you mention his interest in the human condition. As I attempted to point out, like DeLillo, these artists’ portrayal of technology doesn’t undercut having real human characters. Unlike in Pynchon, where there seems to be more of a postmodern overdetermining of people by technology. ‘Million Dollar Hotel’ is beautifully shot, too.