Gender Roles in The Wheel of Time Series

The Wheel of Time is a fantasy epic that sprawls across fourteen novels, all of which earned the New York Times #1 Bestsellers List, and tells a rather complex tale of the Dragon Reborn and the battle of the Light against the Dark One. The Wheel of Time is classified as an adult fantasy, though older teens might find the books approachable. Since the average page count for the series is 826 pages per book, the world is fairly dense with development. The world is set in a post-apocalyptic variant of Earth’s Third Age. 1 In terms of cultures and the societies and gender roles that make up those societies, small details make the world feel alive. There are a few repeated terms throughout this piece, such as Aes Sedai, channeling, saidar, saidin, ta’veren, and ter’angreal.

An Aes Sedai is a woman who can channel the magic source of the world, specifically one who went through rigorous training within the White Tower and holds fast to the White Tower’s rules regarding using the magic she possesses. A channeler is someone who can tap into the magic source of the world and is not gender specific. Saidar and saidin are the female and male halves of the world’s magic source. Ter’angreal are items that use the One Power for a specific purpose and are capable of being created. A ta’veren is someone who can influence the pull of fate within the world. These definitions for these terms have been paraphrased from The Wheel of Time Companion. 2 As the series is so lengthy, specific paginated moments from the books are partially sourced from an archive of the complete work of The Wheel of Time 3, printed works, and selected sections from the fandom Wiki.

Within the series of The Wheel of Time, gender roles are incredibly diverse, depending on where in the world day to day life and expectations are shown and do not mimic modern gender roles significantly, which will be explored in depth in a later segment of this piece. How channeling prejudices affect the world’s gender roles will also be observed. There will be heavy spoilers for The Wheel of Time book series within this article, along with a description of a violation of consent in the consent and bodily autonomy section, so, reader discretion is advised.

Understanding Gender Roles

For the purposes of this article, the following definition of gender roles will be used,

“Gender roles are the behaviors men and women exhibit in the private and public realm. They are the sociocultural expectations that apply to individuals on the basis of their assignment to a sex category (male or female). Usually an individual’s sex is determined by how their genitalia look at birth,”.

Rosemarie Tong 4

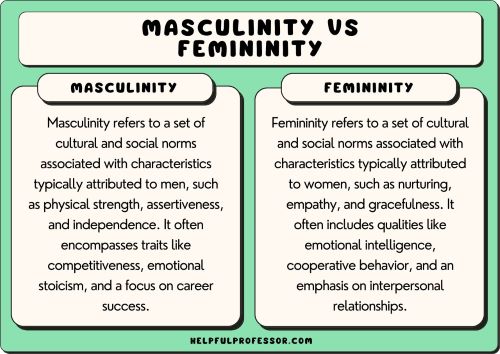

To add to this definition of gender roles, a definition of masculinity and femininity is needed, to better understand how these ideas influenced The Wheel of Time.

Defining Masculinity and Femininity

Masculinity is simply defined as “is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles associated with men and boys. Masculinity can be theoretically understood as socially constructed, and there is also evidence that some behaviors considered masculine are influenced by both cultural factors and biological factors,”. Some of these attributes, at least from a Western perspective include being bold, courageous, and independent. It is often expected that men in Western society are the main breadwinner and provider of the household. 5 However, some gender researchers think that men are not given the ability to express anything other than masculinity, as follows:

“men’s gender is always reduced to this thing of masculinity, leaving little space to explore how men might experience or be gendered outside of an already established subject position of ‘masculinity’. Haywood (2020) also notes that gender literacy has emerged within public commentaries, often in simplistic terms and explanations that inadequately elucidate the complexities and intricacies of social, economic and geographic configurations of gender.”

Andrea Waling 6

In other words, masculinity is rather narrow in its definition, in that, depending on culture, men are expected to provide stability for people who are identified as feminine. Men are often expected to be emotionally removed from situations as well, and are preferred to be tough and self-reliant 7, at least in certain cultures.

Akin to masculinity, femininity is “is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles generally associated with women and girls. Femininity can be understood as socially constructed, and there is also some evidence that some behaviors considered feminine are influenced by both cultural factors and biological factors.” In Western culture, it is expected that women who are feminine are tender, kind, gentle, helpful, and emotional, for example. 8

Throughout the series, The Wheel of Time varies what is considered masculine or feminine, to the point that the protagonists from the Two Rivers, who all seem to understand the Western aspects of masculinity and femininity as outlined above. In addition to this, the two halves of the One Power saidar and saidin operate within more feminine and masculine ideas. For example, when wielding saidar, which only women can do, it is often described as gently guiding one’s way through a river. By contrast, saidin is described as balancing on a knife’s edge, lest the power overwhelm the man forcing it to do what he wants. 10. Masculinity and femininity can have some negative traits as well, many of which also show up in the Wheel of Time. Toxic gender roles are discussed next.

Defining Toxic Gender Roles

Before analyzing if the characters in The Wheel of Time fall into certain toxic gender traits, it is important to discuss what toxic gender traits are. A common term that many might recognize is toxic masculinity. Toxic masculinity refers to the emotional manipulation that men engage in to deceive or otherwise harm others. One particular study determined that males were more likely to be emotionally manipulative and statistically suppressed feminine gender roles. Emotional manipulation often predicts certain qualities like aggression and insincerity, and in some instances, trait psychopathy, meaning that emotional manipulation is used for less sincere reasons.

Psychopathy can include callousness or deception, and can also lead to more severe behaviors. In this study, men self-reported using emotional manipulation more than their female participants, though both males and females thought that males were more emotionally manipulative. The study suggests that women have a greater emotional skill than men, especially in regard to interpersonal situations. Part of this could be because of societal expectations for men to be dominant and take action, as opposed to the expectation that women should be more refined and subdued, therefore, emotional manipulation would look different for men and women. The study found that, in addition to being more emotionally manipulative, men also self-reported more indicators of psychopathy than females, meaning that they are more likely to be deceptive with their emotional manipulation. 11

Following that, toxic femininity can be considered a too-rigid form of femineity, where certain people groups are excluded from the pursuit of equality. It is possible that certain ideologies seeped into feminism that reinforce expected gender roles or the rejection of them to exclusion of accepting other female identities, such as trans women, for example. 12 This idea that ideology about other genders or traits spurn on the less favorable attitudes others believe is extremely evident with the Aes Sedai and men in The Wheel of Time.

These ideas of toxic or restrictive gender roles are present in The Wheel of Time and are examined in the protagonists’ journeys of growth. Mostly, it is easy to see where toxic traits appear in the characters of Mat and Nynaeve at the outset of their journey, which is covered in detail later. For now, channeling and its effect on the world of The Wheel of Time is examined next.

Channeling and its Effect on the World

Men were responsible for an event of the world known as The Breaking. During this time, a singular male channeler brought ruin to the world by allowing the Dark One to taint saidin and eventually went mad with paranoia and power (The Eye of the World, 45-47). This man brought an end to the Second Age, in which men and women who could channel were held in high regard as the servants of all–the Aes Sedai. The Second Age functioned under an economy where no poverty existed, and men and women equally, but especially those who could channel, expected to serve their community to the best of their capability. After The Breaking, the women who could channel did their best to quell the scourge of maddened male channelers and rebuild the world with The White Tower as an object that holds the order of those who can channel in a precise place within society as of the Third Age. 13

Men who can channel in the Third Age are often gentled–cut off from the Source that makes it possible to channel saidin, once they are discovered by Aes Sedai, often the Red Ajah, who make it their mission to gentle as many men channelers as possible, usually with little concern to their humanity in the process 14. Other culture’s channelers, such as the Sea Folk forced their male channelers to drown or be deserted on an island without provisions 15, or, they are assumed to simply go mad and die after prolonged exposure to the Source (The Eye of the World, 67). Because men who can channel broke the world, men are not often trusted with power beyond that which can be considered militaristic or political. By contrast, women are not held to the same scrutiny and have more influential power within societies without being feared.

Matriarchy versus Patriarchy

The Wheel of Time has split its cultures into ones with either a more patriarchal or matriarchal society. A paternal society is one that is run with men in leadership roles within governments. Men in patriarchal societies are not often held to the same scrutiny as women, but men are usually in a hierarchy. Objective patriarchy at its worst keeps women out of high paying jobs or positions of power. 16 By contrast, a matriarchal society is one as follows where “The patterns at the political level follow the principle of consensus, which means unanimity regarding each decision. To manifest a principle like this in practice, a society must be specifically organized to do so, and matrilineal kinship lines are, once again, the starting point,”. 17

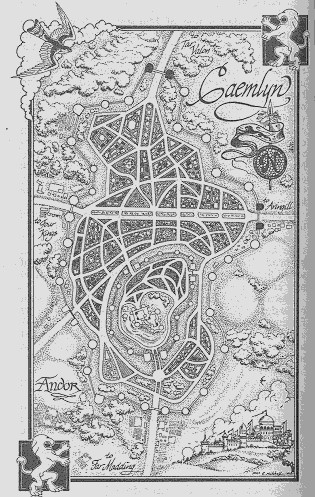

Furthermore, in certain cultures, the grandmother is the head of the household, with all her daughters and granddaughters living with her. In some instances, the youngest woman remains unmarried and takes over the family household when she’s old enough. In this kind of structure, men are often expected to move into their wife’s household and work for his family, rather than the woman relocating to her husband’s house. 18 Women within matriarchal societies can sometimes be subject to scrutiny by men who are accustomed to being in power, and as a result, the men in the society may feel repressed. This idea of passing down one’s legacy down to a daughter or to the daughters of a rival house is shown in the more political aspects of Caemlyn, including their strong ties to the Aes Sedai in the White Tower in The Wheel of Time, discussed below.

For example, Tear is ruled by High Lords who do not really have strong ties to The White Tower. In fact, the people of Tear actively fear anything that has to do with channeling. 20 By contrast, Caemlyn has a monarchy where it is traditionally ruled by a queen. The queen’s Daughter Heirs are expected to place claims to the throne and train at the White Tower 21, whereas men of the royal family are expected to train at the White Tower to become protectors of the Queen. 22 Throughout the series, it is more likely that the stronger ties a place has to the White Tower, the more likely a place will be a matriarchy, whereas if a place distrusts the White Tower or does not have a strong connection with the Aes Sedai, then the society will be structured as a patriarchy.

There are some exceptions to this generalization in the societies of the Aiel and the people of the Two Rivers. Both of these societies have a group of men and women in leadership roles, working together to make their respective society function. The Aiel have the Wise Ones who make final judgements on decisions as women who can channel, and male chieftains who consult with the Wise Ones about smaller tribe issues. 23 Within the Two Rivers, the two groups who run the society are the Village Council and the Women’s Circle who work together to solve issues that arise in general, with the sentiment in the Two Rivers existing as followed:

“Most of the men rolled their shoulders and said, “Well, we’ll survive, the Light willing.” Some grinned and added, ‘And if the Light doesn’t will, we’ll still survive.’

That was the way of most Two Rivers people. People who had to watch the hail beat their crops or the wolves take their lambs, and start over, no matter how many years it happened, did not give up easily. Most of those who did were long since gone…’What are we going to do about Nynaeve, al’Thor?” Congar demanded. “We can’t have a Wisdom like that for Emond’s Field.’

Tam sighed heavily. ‘It’s not our place, Wit. The Wisdom is women’s business.’

…’What business of yours is the Wisdom, Wit Congar?” roared a woman’s voice. Wit flinched as his wife marched out of the house. Daise Congar was twice as wide as Wit, a hard-faced woman without an ounce of fat on her. She glared at him with her fists on her hips. ‘You try meddling in Women’s Circle business, and see how you like eating your own cooking. Which you won’t do in my kitchen. And washing your own clothes and making your own bed. Which won’t be under my roof.'”.

The Eye of The World p. 52

In addition to this example, the factions of the Aes Sedai and the Children of Light exemplify the ideas of a matriarchy and a patriarchy and their more toxic traits within the series. The Aes Sedai in the White Tower use men and control them as their guardians, as evidenced by Mat’s assertion on seeing Moiraine and Lan when they arrived in the Two Rivers, “‘Anyway, he defers to her, does what she says. Only he isn’t like a hired man. A soldier, maybe. The way he wears his sword, it’s part of him, like his hand or his foot.’,” (The Eye of the World, 61), though it comes at a great cost to the Aes Sedai if her Warder dies. When the Warder is bonded to his Aes Sedai, he swears to her guidance and to protect her and follow her orders. Some groups within the White Tower dislike men and do not usually take Warders, such as the Red Ajah. The Aes Sedai often think that their way must be followed without question, despite many in the Third Age not trusting them. 24 The Children of Light are a faction of men who despise women who channel and call Aes Sedai witches. They also uphold their ideas about liberating the world from everything they view as not being of the Light. They have a rather militaristic structure and seem to look down on anyone who does not agree with their worldview. The Children of Light claim to only want the Light to prevail and nothing more, but the group itself seems to constantly vie for power throughout the series. 25

These two factions are good examples of the ideas found in the next section of this article, which deals with the ideas of trust and power. The way that the Wheel of Time handles these ideas is interesting. Trust and power will be defined in the next section as well.

Trust Versus Power in Regards to Men and Women

Throughout The Wheel of Time series, there are examples of men being viewed as more trustworthy, but women being the ones holding the power. An example of this is clearly displayed within Mat’s initial thoughts on women who can channel. Another example of this mindset is seen with how men react to the Children of Light. The men within the Children of Light appear completely trustworthy, especially to those who also distrust Aes Sedai.

Another example of this ideology is seen when The Black Tower is created and how Aes Sedai of the White Tower react to it. Most of them believe that a man with power, especially the ability to wield saidin are not to be trusted. This is particularly evident when Elaida forces her way to Amyrlin Seat and attempts to either have the Black Tower come under Tar Valon law or dismantle it completely after meeting resistance. 27

Of course, a decent part of The Wheel of Time deals with whether these ideologies of society are inherently correct. There are plenty of times where, because women refuse to communicate their plans plainly, especially in the presence of men lead to issues. However, despite this breakdown in communication, the women are usually found to be trustworthy, whereas the men who are implicitly trusted usually commit some type of betrayal in the name of amassing power in some way. As this is a common theme throughout the book series, it is difficult to reference specific examples. Following trust and power, it is important to also consider how the people groups in The Wheel of Time handle the ideas of consent and bodily autonomy.

Consent and Bodily Autonomy

In some cultures within the books, such as with the Seanchan, the act of channeling is done without consent or bodily autonomy, rather a sul’dam tells the damane when and how she will channel. If the damane refuses or otherwise disobeys, they are punished, often as though they are animals rather than women. 28 This notion is directly at odds with how Andor treats women channelers, who are trained in how to channel responsibly but otherwise have free will with how and when they channel. Other cultures, like the Aiel, give women more bodily autonomy than Tear, in that women are allowed and almost expected to fight, unless they are made gai’shan. In that instance specifically, the gai’shan, be they man or woman, are to be subservient to their captors for a year and a day to regain their honor. In addition to this, the punishment for hurting a woman, especially a Wise One, is severe. 29

In regards to a place like the Two Rivers, consent is understood as proper and bodily autonomy is respected. This makes an incident that happens at Mat’s expense somewhat shocking, as he is essentially coerced by a queen after leaving the Two Rivers, which is detailed in a later section. By contrast to the proper guidelines set forth on Two Rivers folk, the Sea Folk have a rigid chain of command, set on the idea of women steering the ships with saidar and maintaining control in public, and the men on the ships maintain control in private, and this practice is consented to. This practice also gives Sea Folk women a high amount of bodily autonomy in regards to decisions they make in their day to day lives. 30 Finally, the Aes Sedai arguably are women who have the most autonomy among women in Andor, and they broker consent and respect within their own politics, which extends to their Warders, to the point that bonding a Warder without consent is gravely frowned upon, due to the lack of consent in the bond, which permanently links the Aes Sedai’s and Warder’s physical feelings and emotions, as in the case of Alanna and Rand al’Thor 31, and bonding a Warder without being a full Aes Sedai violates White Tower rules. 32

Magic versus Might

When magic is considered in the series, it is the women who can channel who deftly know how to use the Source. They spent hundreds of years training with saidar and how to guide it into what they want, to the point that the White Tower has built up specific guidelines for who will be able to become an Aes Sedai, as previously established. Given what happened to the men in the Second Age, as referenced earlier, men do not have as much power with the Source.

However, in terms of physical might, that is more of a masculine trait. Perrin Aybara is a perfect example of this as a character to the point that his struggle deals with might and needless violence over creation and fighting when necessary. As far as Andoran culture is concerned, the men are the ones who fight and die in battles, and the women are meant to be protected.

The slight exception to this rule within the series is found within the men who can channel. They have might within The Source and must control saidin rather than guide the Source into what they want to see. As a result, male channelers are stronger with the magic of the series on average, but it is something that they must continually work with to achieve. There is also a stigma around men who can channel, particularly one man known as the Dragon, as seen in this exchange on Bel Tine in The Two Rivers:

“‘The standard of the Dragon has been raised, and men flock to oppose. And to support.’

One long gasp left every throat together, and Rand shivered in spite of himself.

‘The Dragon!’ someone moaned. ‘The Dark One’s loose in Ghealdan!’

‘Not the Dark One,’ Haral Luhhan growled. ‘The Dragon’s not the Dark One. And this is a false Dragon, anyway.’

‘Let’s hear what Master Fain has to say,’ the Mayor said, but no one would be quieted that easily. People cried out from every side, men and women shouting over one another.

‘Just as bad as the Dark One!’

‘The Dragon broke the world, didn’t he?’

‘He started it! He caused the Time of Madness!’

‘You know the prophecies! When the Dragon is reborn, your worst nightmares will seem like your fondest dreams!’

‘He’s just another false Dragon. He must be!’

‘What difference does that make? You remember the last false Dragon. He started a war, too. Thousands died, isn’t that right, Fain? He laid siege to Illian.’

‘It’s evil times! No one claiming to be the Dragon Reborn for twenty years, and now three in the last five years. Evil times! Look at the weather!’…’I do know,’ he said, too casually, ‘that he can wield the One Power. The others couldn’t, But he can channel. The ground opens beneath his enemies’ feet, and strong walls crumble at his shout. Lightning comes when he calls and strikes where he points. That I’ve heard, and from men I believe.’

The Eye of the World p. 66 -67

It is clear to see from this exchange that men seem to be more concerned with the militaristic implications of the Dragon being reborn in their age, and the group of men and women both know that the Dragon broke the world once. However, they mistakenly assume that the Dragon is teamed up with the Dark One to destroy the world. This idea seems to take what power the men do have and are trusted with and strips it away from them, due to their fear of what one man who can channel is capable of.

Now that the aspects of matriarchy and patriarchy, trust and power, and might and magic have been examined in terms of how gender roles work within the world of the Wheel of Time, what makes a gender role toxic versus healthy will be discussed in the next section. No gender as it has been portrayed so far is without fault in regards to the upcoming subject matter. Toxic gender roles versus healthy ones makes up a majority of the conflict within the series, as shown earlier.

Protagonist Gender Roles in the Series

The main cast of characters in The Wheel of Time is quite vast, as there are a lot of seemingly minor characters who have larger roles within the series. For the purposes of this piece, focus is kept on Rand, Mat, Perrin, Egwene, Nynaeve, and Elayne. Much of the major plot points revolve around these six characters throughout the series. A brief examination might be made to characters outside of this grouping of six, particularly if how the character acts or is portrayed in the world adds something to the examination of gender roles in The Wheel of Time.

These six protagonists have a variety of reactions to the world around them, which are informed by the roles they grew up with in the Two Rivers. Some of them hold fast to the roles expected of them from birth, while others learn to blend their experiences into a new kind of role. The confirmation or subversion of gender roles, along with the original societal roles and resulting culture shock from leaving those expectations are examined in the following two sections. These next sections offer the foundation to the six selected protagonists, and, from there, a larger discussion around how Jordan viewed gender roles can be formed.

Confirmation or Subversion of Gender Roles

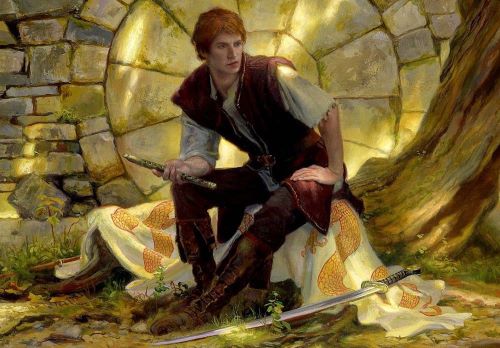

Many of the conflicts around the events in The Wheel of Time involve some kind of confirmation or subversion of the role a character is meant to fulfill. For example, Rand constantly walks the knife’s edge between being the world’s savior or its destroyer, because of how the different cultures of the world perceive his abilities as a male channeler and as the Dragon Reborn. By contrast, Perrin subverts what becomes expected of his personality due to his notoriety as a wolf brother. Meanwhile, Mat is seen as a Two Rivers man in the historical sense, due his memories from past lives thrust upon him by the Aelfinn and Eelfinn in the Tower of Genji.

Likewise, Nynaeve feels caught between her roles as Wisdom, the one who helped nurture Rand, Mat, and Perrin in their youth, and the one who mentors Egwene in the ways of becoming a Wisdom from her time in the Two Rivers, and what quickly becomes expected of her as a channeler in training in the White Tower. Egwene seemingly leans into her new expectations as opposed to keeping up with the role expected of her in the Two Rivers. Meanwhile, Elayne faces the conflict of being seen as the Daughter-Heir to Queen Morgase, and living life in the Tower as well as facing what it means to fall in love with Rand. Detailed explanations of these ideas are examined below, drawing in examples from other cultures and those characters who exemplify them where appropriate.

Two Rivers Societal Roles and Culture Shock

As most of the characters examined in this article come from the Two Rivers, it is important to understand what is expected for an average man or woman in that society as opposed to the larger country of Andor. The Two Rivers remains removed from Andoran rule, due to an agreement forged between Caemlyn and the people who fought for their land. As a result, most Two Rivers people pride themselves on being self-sufficient within their community. Rand, as mentioned earlier, along with his father, Tam, are seen as removed from the internal community of the Two Rivers, as they live so far away from the village proper, as described, along with Rand’s parentage as follows:

“With a guilty start Rand returned to watching his side of the road, Tam’s matter-of-factness reminding him of his task. He was a head taller than his father, taller than anyone else in the district, and had little of Tam in him physically, except perhaps for a breadth of shoulder. Gray eyes and the reddish tinge to his hair came from his mother, so Tam said. She had been an outlander, and Rand remembered little of her aside from a smiling face, though he did put flowers on her grave every year, at Bel Tine, in the spring, and at Sunday, in the summer.

Two small casks of Tam’s apple brandy rested in the lurching cart, and eight larger barrels of apple cider, only slightly hard after a winter’s curing. Tam delivered the same every year to the Winespring Inn for use during Bel Tine, and he had declared that it would take more than wolves or a cold wind to stop him this spring. Even so they had not been to the village for weeks. Not even Tam traveled much these days. But Tam had given his word about the brandy and cider, even if he had waited to make delivery until the day before Festival. Keeping his word was important to Tam. Rand was just glad to get away from the farm, almost as glad as about the coming of Bel Tine….

With a worried frown he peered into the woods around them; it looked different than it ever had before. Almost since he was old enough to walk, he had run loose in the forest. The pondsand streams of the Waterwood, beyond the last farms east of Emond’s Field, were where he had learned to swim. He had explored into the Sand Hills-which many in the Two Rivers said was bad luck-and once he had even gone to the very foot of the Mountains of Mist, him and his closest friends, Mat Cauthon and Perrin Aybara. That was a lot further afield than most people in Emond’s Field ever went; to them a journey to the next village, up to Watch Hill or down to Deven Ride, was a big event. Nowhere in all of that had he found a place that made him afraid…

“I could do with a pipe,” Tam said slowly, “and a mug of ale where it’s warm.” Abruptly he gave a broad grin. “And I expect you’re eager to see Egwene.

Rand managed a weak smile. Of all things he might want to think about right then, the Mayor’s daughter was far down the list. He did not need any more confusion. For the past year she had been making him increasingly jittery whenever they were together. Worse, she did not even seem to be aware of it. No, he certainly did not want to add Egwene to his thoughts.”

The Eye of the World pp 50-51

Despite the distance, Rand and Tam enjoy some semblance of acceptance into the Two Rivers community. The societal expectations for the Two Rivers, in regards to men, include the following roles: being good at firing a Two Rivers bow, contributing to the community with your trade, and, eventually, taking part in village affairs as part of the Village Council (The Eye of the World, 51-52).

For women, like Nynaeve and Egwene, the Two Rivers society expects them to either provide healing, in the case of the village Wisdom and her mentees, or provide more domestically to the village through cooking, running the inn, and marrying their betrothed. The women of the Two Rivers also conduct meetings in village affairs with the Women’s Circle, which often finds itself at odds with the Village Council. Women in the Two Rivers who can channel do not concern themselves with training at the White Tower, as the village Wisdom and her mentees are the ones who carry the spark of the One Power within them (The Eye of the World, 70). On the note of outsiders, Two Rivers folk are suspicious of the people living in the next town over, and it is uncommon for someone born in the Two Rivers to leave, as Rand once mentions to Egwene (The Eye of the World, 71).

However, outside of the Two Rivers, societal roles are different, depending on what region of the world one is in, much like in real life. For example, Elayne, despite being Daughter-Heir of the Rose Throne of Caemlyn, is expected to go to the White Tower to train, as are most others who the Aes Sedai find capable of channeling. The White Tower contains its own brand of harsh politics and expectations of women and men. The Aiel, who play a larger role in this piece below, pride themselves on women who fight better than men, and are led by a group of women called the Wise Ones. It makes sense, then, that when the main characters interact with these varied groups, culture shock occurs.

As stated prior, Rand, Mat, Perrin, Nynaeve, Egwene, and Elayne all react to this culture shock differently. In the case of Rand, for example, he does not know how to handle the way the larger world around him functions, but he tries to learn what he can. Of course, in Rand’s specific case, as The Dragon Reborn, the world as a whole expects far more from him than he can imagine. Mat, conversely, decides to woo women and treat his newfound expectations as a game. He spends much of the first and second books incapacitated due to a cursed dagger he steals from Shadar Logath. Perrin struggles to find where what he had always expected to do with his life fits into the other expectations societies have for him being both ta’veren and a wolf brother. As a result, he instantly gravitates toward a peace loving culture like the Tinkers to fit in how he can with his trade of blacksmithing.

For Nynaeve, she struggles with becoming lower than her title of Wisdom at the White Tower. She refuses to bend to silly rules concerning that of her new station as a novice who blocked her ability to channel at will, which earns her quite a few lashings from the Mistress of the Novices. Egwene revels in her newfound station and expectations of novice, though it creates tension between her and Nynaeve, and she excels at the lessons given to her. Elayne chooses not to allow her station as Daughter-Heir influence what the White Tower expects from her. These societal expectations and culture shocks are further fleshed out as part of the section below.

Protagonist Roles vs. Narrative Growth

Each of the main characters struggle with their protagonist role as it relates to their narrative growth. This growth also influences their newly, outside of the Two Rivers or Caemlyn, in Elayne’s case, established gender roles as they come into their own. Rand changes from a farmer outside of Edmond’s Field, described as follows, “Like most Two Rivers folk, Rand had a strong stubborn streak. Outsiders sometimes said it was the prime trait of people in the Two Rivers, that they could give mules lessons and teach stones” (The Eye of the World, 53) to the Dragon Reborn. Perrin goes from a blacksmith’s apprentice who is larger than other Two Rivers men (The Eye of the World, 66) to a Wolf Brother and lord and leader of men. Mat moves both into and away from bit of a prankster whose “brown eyes twinkled with mischief, as usual…Mat never seemed to grow up” (The Eye of the World, 55) to a gambling general married to the Empress of the Seanchan.

As for the female protagonists, their journeys can broadly be defined in the following statements. Egwene transforms from Two Rivers Wisdom in training implied to be betrothed to Rand (The Eye of the World, 70) to Armyrlin Seat of the White Tower during the Last Battle. Nynaeve leaves behind her role as the Two Rivers Wisdom who is extremely not tolerant of behaviors outside of how Two Rivers folk should act, with a temper to match, as stated by Rand, “‘You know Nynaeve’s temper. When Cenn Buie called her a child last year, she thumped him on the head with her stick, and he’s on the Village Council, and old enough to be her grand¬ father, besides. She flares up at anything, and never stays angry past turning around.’,” (The Eye of the World, 60) and works her role into being Best Healer of the Age and showcases the mulicultural influences that got her there. Elayne changes from a girlish Novice in training Daughter-Heir into Queen of Andor and Cahairien and a First Sister to an Aiel who is married–in Aes Sedai terms–to Rand with two other women.

To add some depth to this progression, the following examples show the kind of conflicts each of the characters faced in major moments that fundamentally changed them and the new roles they accepted in order to attempt to save the world. These examples are broken down first by Rand, Mat, and Perrin, followed by Nynaeve, Egwene, and Elayne. A few other characters, such as Aviendha and Moiraine are mentioned in this section, as they helped shape quite a few of the protagonists.

Rand, under the mentorship of Lan and his training, begins to understand that his role as ta’veren at the very least is to harden himself to the influence of the Dark One, for the greater good, and he often repeats, “Death is lighter than a feather. Duty, heavier than a mountain.” throughout his journey. 35 Once he reveals himself to be the Dragon Reborn, the stigma of men who channel makes people fear him, others want to use his influence for their own gain, and still others, particularly the Red Ajah of the White Tower want to cut him off from his new role and power. Through attempts to figure out his new role as a man with power, the Aiel, especially Aviendha, try to help him see how the Aiel culture functions, with the hope that it will better temper some of his brashness.

Unfortunately, Rand struggles to cope with his trauma from Dumai’s Well, where he had been kept in a box and beaten by Aes Sedai, and the Dark One’s taint makes his past memories as Lews Therin appear to him in the way of a crazed, persecutor type split persona. 36 When he had already been forced to take power and authority where he could, the notion of being controlled by anyone, along with the madness from saidin, and the weight of knowing that he would either save the world, destroy it, or die before he could do either, Rand became too consumed by Lan’s teaching of hardening one’s feelings and carrying his mountainous burden alone to let anyone else near him, save for Nynaeve, Elayne, Aviendha, and Min. 37

Eventually, towards the start of the events that would lead to The Last Battle, Rand figures out how to cleanse saidin and realizes that he acted too heavily on toxic impulses in a moment of desperation, where he nearly strikes down Tam in a fit of rage, due to how hardened to his emotions he’d become while he contemplates whether or not to just end it all on Dragon Mount. Once he has the realization that living with those mistakes gives him a chance to make things right, Rand is able to come to terms with what he’s done as The Dragon Reborn, and he recognizes that the voice in his head throughout the series as his past life as Lews Therin Telamon in the Age of Legends. 38 He allows himself to be emotional, to an extent, to those he trusts and apologizes about the hurt he’s caused others when he was lashing out. Despite this forward momentum, Rand still views his death as a certainty and becomes somewhat numb to it, and refuses to believe there is a way for him to survive The Last Battle. In the end, Rand acknowledges his support network and is able to seal the Bore and bring about an end to the Dark One, potentially for all time, depending on interpretation of the event. 39

Mat becomes influenced by Thom and falls into gambling and other business that the Two Rivers would frown upon. He maintains a rather patriarchal view of women, insisting that they are prone to act like they don’t owe anyone anything, and, at least in the beginning of the series, he decides to learn about other cultures by seeing if he can woo someone to keep him warm at night. Some of this behavior tones down when he is coerced by Queen Tylin, though he admits to himself that even he doesn’t press when a clear no is given, though the queen refuses Mat’s lack of consent and refusal by writing him a letter, informing him that she is having his things moved into her room. 40 When Mat meets Tuon, he begins to treat her as his equal, which she finds amusing and insists that he must learn the ways of her culture if she is to accept him.

Unlike Rand or Perrin, Mat insists on outrunning his fate, afraid that Rand is going mad from channeling and will kill him, so he avoids staying near Rand or Perrin at all costs, and ends up creating a band of warriors from multiple cultures. At the end of it all, Mat slowly comes to understand Seanchan culture, but gets his wife to compromise on the treatment of women who can channel, insisting that she needs to accept his culture, too. In this way, Mat transforms from a prankster with no idea of his future, who uses humor to cope, into someone who leads troops into the Last Battle as a Seanchan general and brokers an understanding between the Seanchan and Andor. 42

Perrin learns to lead people over time, while doing his best not to give into his wolf brother nature. Perrin also experiences a rather toxic relationship with his wife, Faile, which is fraught with misunderstandings, due to their different cultures. In Faile’s culture, it is acceptable for a woman to yell at and hit a man to goad him into fighting back to get what she wants, which is something that Perrin views as unacceptable, as he is used to apologizing for upsetting someone like that, not rising to the bait. Perrin, similarly to balancing his beast-like nature due to his wolf brother abilities, comes to balance when to stand up for himself against Faile’s goading, which, leads him to take charge of the people of the Two Rivers into the Last Battle, not by fighting, but by providing arms services. 44

Nynaeve starts her journey by being as tough and formidable as a Two Rivers man, carrying a stick she uses to thump senseless men when they mistreat her, and is shown as mothering, if sternly, towards Rand, Mat, and Perrin. This aspect of her character has to do with the fact that she was considered too young to be the village Wisdom (The Eye of the World, 69). This particular chip on her shoulder lasts until her block on channeling breaks, but compounds when she seeks training at White Tower, since she is considered to be too old to be a novice by Tower standards. Nynaeve acts angry at every little thing during her travels, as it is the one way she can reliably grasp the Source, and this breaks after she experiences being married in the Sea Folk way–where things she considers private between her and her husband inferably happen in public.

She goes on to break her block on saidar when she needs to channel to save her husband, Lan’s, life. She becomes accustomed to her marriage in the way that the Sea Folk had her agree to–the one with control in public must listen to the spouse in private, which tempers her mood. 45 She even starts to present a bit more softly feminine by wearing dresses in styles or colors that she thinks Lan likes. By the time that Nynaeve shows up at The Last Battle, she wears clothing from all over the world, in a display that strikes Egwene as so different from the Wisdom of The Two Rivers. 46

Egwene begins The Eye of the World curious about the outside world, in awe of Moiraine. She hates the Seanchan for the torture they put her through with an a’dam which stripped her of the free ability to channel saidar, and the effects of that incident stay with Egwene until the end of the series. The Wise Ones gave Egwene the most influence by introducing her to the Aiel culture and gave her insight on her Talent of Dreaming. During her imprisonment at the White Tower before becoming Armylin Seat, Egwene uses what she learned from the Aiel to harden herself and not break, the way she did under the Seanchan.

However, Egwene makes a mistake Moiraine warned her about during her initial training in a fit after losing Gawyn, her Warder, and becomes more like how she envisioned Nynaeve in the Two Rivers at the beginning of their journey. She draws on the power of sa’angreal and saidar almost to the point of burning up, in an effort to do the most to end the Last Battle and reunite with Gawyn in death, which causes her to leap into figuring out how to reform cracks forming in reality and bring about her end. Egwene ultimately learned to let go of her childishness, figure out who she loved by distancing herself from Rand, and used her own voice and power to save the world in her own right, no matter the cost. 47

Elayne knows her path might include the throne of Caemlyn and treats it as a far off potential birthright. She becomes swept up in Tower secret politics and is infatuated with Rand and Aviendha, in a way. She accepts Aiel culture enough that she is First Sister to Aviendha and suggests that she, Aviendha, and Min all bond Rand as their Warder. She takes note of how others channel not in the White Tower, manufactures tar’angreal on her own after scientific study. Elayne shows her smarts in the end by gaining the throne of Caemlyn and Cairhien after protecting both cities by waging a strategic war while pregnant with Rand’s children. In The Last Battle, she shows that she has gone from rich Novice to accomplished Queen and Aes Sedai, and is capable of maintaining and ensuring harmony within Andor by recognizing the Two Rivers as its own region. 48

The Wheel of Time’s Commentary on Gender Roles

From the analysis above, The Wheel of Time gives the following commentary on gender roles: men and women act in largely predictable ways, but sometimes, those roles are subverted and complex. The Wheel of Time built up a robust world where many cultures act differently and yet also hold similarities. By understanding these different facets of the world, Rand drafts the Dragon’s Peace, which solves most of the world’s problems in regards to his role in the world. There are a few problems with The Wheel of Time‘s commentary on gender roles in terms of more modern concepts of gender, which are detailed below.

While there are nods to things in the LGBTQ+ umbrella, such as being gay, in the case of a minor character in Memory of Light 49, lesbian, in the case of pillow friends in the White Tower 50, potentially bi, depending on how one views Elayne and Aviendha’s relationship with themselves as First Sisters and Rand, as well as Moiraine and Siuan going from pillow friends to ending up with men, and polyamorous, in terms of Rand, Elayne, Aviendha, and Min 51, characters, nothing is explicitly represented. Gender non-confirming characters are confined to maybe two characters, and both instances are inferred. One inference is the character of Nynaeve, who has a rather masculine personality as far as the White Tower and Two Rivers are concerned, as detailed earlier.

The other, more overt inference of a gender non-conforming character is that of Min, who prefers to keep her hair short, is flat chested, hates dresses, and almost takes pride in being mistaken for a man. Despite this pride, she dresses in a non-gender specific way. The most evidence beyond these characteristics that Min could be considered nonbinary is that she experiences anger at her birth name of Elmindreda and frustration at needing to appear overly feminine with dresses and long, curly hair. 53

With these aspects of The Wheel of Time‘s commentary of gender in mind, it is interesting to consider how these aspects might be rephrased with more modern terminology. Despite this possible facet that dates The Wheel of Time series in its print form, the world that was built in such a way that inclusion exists, which helps the series stay with readers as time moves forward. This point leads nicely into the conclusion.

Did Jordan place Modern Gender Roles in high Fantasy? This question is somewhat complex to answer, given the complexities of the characters Robert Jordan, and later Brandon Sanderson, filled his world with. There is a constant back and forth as to whether or not men can be trusted over women and vice versa. The issue of whether or not a man or a woman can channel changes the perception and role that the man or woman is meant to fulfill. The question of modern gender roles in high fantasy is further compacted by the fact that within the Wheel of Time’s world gender roles appropriately vary by culture, shown mostly through the main protagonists’ development and how they react when confronted by gender roles from a culture that is not their own.

It would take much more research into gender roles and further examples from minor characters within the series to determine whether or not the gender role shown in the series qualify as entirely modern. However, it can be strongly argued that Robert Jordan managed to bring in extremely authentic and varied gender roles into his fantasy epic. While long, The Wheel of Time feels alive with descriptions of people and places that tie it, much like the main characters do to the plot, into a cohesive, complicated and complex world, gender roles included.

Works Cited

- To Everything, Turn, Turn, Turn: The Wheel of Time Beginner’s Guide. (n.d.). Audible Blog. Retrieved May 14, 2024, from https://www.audible.com/blog/article-the-wheel-of-time-beginners-guide ↩

- Jordan, R., McDougal, H., Romanczuk, A., & Simons, M. (2015). The Wheel of Time Companion (pp. 23–24, 165, 635, 714, 737). Tor Books. ↩

- Jordan C Robert The Wheel Of Time Complete Works 13 Book. (n.d.). In Internet Archive. Retrieved April-May 2024, from https://archive.org/details/jordan-c-robert-the-wheel-of-time-complete-works-13-book/mode/2up ↩

- Tong, R. (2012). Gender Role – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Www.sciencedirect.com. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/psychology/gender-role ↩

- Wikipedia Contributors. (2019, April 11). Masculinity. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masculinity ↩

- Waling, A. (2022). “Inoculate Boys Against Toxic Masculinity”: Exploring Discourses of Men and Masculinity in #Metoo Commentaries. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 31(1), 106082652210920. https://doi.org/10.1177/10608265221092044 ↩

- Men and emotions. (n.d.). MensLine Australia. https://mensline.org.au/mens-mental-health/men-and-emotions/#:~:text=Men%20often%20feel%20that%20they ↩

- Wikipedia Contributors. (2019, April 16). Femininity. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Femininity ↩

- Drew (PhD), C. (2023, July 13). Masculinity vs Femininity: Similarities and Differences (2023). Helpfulprofessor.com. https://helpfulprofessor.com/masculinity-vs-femininity/ ↩

- One Power. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/One_Power#Male_and_female_differences ↩

- Grieve, R., March, E., & Van Doorn, G. (2019). Masculinity might be more toxic than we think: The influence of gender roles on trait emotional manipulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, 157–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.09.042 ↩

- McCann, H. (2020). Is there anything “toxic” about femininity? The rigid femininities that keep us locked in. Psychology & Sexuality, 13(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2020.1785534 ↩

- Jordan, R., & Patterson, T. (2001). The World of Robert Jordan’s The Wheel of Time (pp. 29-39, 82–119). Macmillan. ↩

- Severing. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved April 23, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Severing#Gentling ↩

- The Gathering Storm/Chapter 5. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 14, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/The_Gathering_Storm/Chapter_5 ↩

- Hill, Michael R. 2009. “Patriarchy.” Pp. 628-633 in Encyclopedia of Gender and Society, edited by Jodi O’Brien. Vol. 2. Los Angeles: Sage. ↩

- Goettner-Abendroth, H. (2018). Re-thinking “Matriarchy” in Modern Matriarchal Studies using two examples: The Khasi and the Mosuo. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 24(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2017.1421293 ↩

- Gneezy, U., Leonard, K. L., & List, J. A. (2009). Gender Differences in Competition: Evidence from a Matrilineal and a Patriarchal Society. Econometrica, 77(5), 1637–1664. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25621372 ↩

- Wheel of Time II by Dubisch on DeviantArt. (2011, January 31). Www.deviantart.com. https://www.deviantart.com/dubisch/art/Wheel-of-Time-II-195554579 ↩

- Tear. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 14, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Tear ↩

- Queen of Andor. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 14, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Queen_of_Andor ↩

- First Prince of the Sword. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 14, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/First_Prince_of_the_Sword ↩

- Wise One. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 14, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Wise_One ↩

- Aes Sedai. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 14, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Aes_Sedai?so=search ↩

- Children of the Light. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 14, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Children_of_the_Light?so=search ↩

- Elaida do Avriny a’Roihan by end5er on DeviantArt. (2020, January 11). Www.deviantart.com. https://www.deviantart.com/end5er/art/Elaida-do-Avriny-a-Roihan-826542725 ↩

- (n.d.). Elaida a’Roihan’s White Tower [Review of Elaida a’Roihan’s White Tower]. A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 15, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Elaida_a’Roihan’s_White_Tower?so=search ↩

- to, C. (2023). Sul’dam. A Wheel of Time Wiki; Fandom, Inc. https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Sul%27dam ↩

- Aiel law. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Aiel_law?so=search ↩

- to, C. (2023). Atha’an Miere. A Wheel of Time Wiki; Fandom, Inc. https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Atha%27an_Miere ↩

- Alanna Mosvani. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 15, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Alanna_Mosvani#Bonding_Rand ↩

- Bonding. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 15, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Bonding ↩

- wot-tidbits. (n.d.). Perrin, Rand and Mat by juliacarl_art. Tumblr. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://wot-tidbits.tumblr.com/post/675201938144493568/perrin-rand-and-mat-by-juliacarlart ↩

- Prabhu, V. (n.d.). The Two Rivers Wheel of Time Fan Art [Review of The Two Rivers Wheel of Time Fan Art]. ArtStation. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://www.artstation.com/artwork/zD80OD ↩

- Lan Mandragoran. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Lan_Mandragoran ↩

- to, C. (2023). Battle of Dumai’s Wells. A Wheel of Time Wiki; Fandom, Inc. https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Battle_of_Dumai%27s_Wells ↩

- o, C. (2023). Rand al’Thor/Chronology. A Wheel of Time Wiki; Fandom, Inc. https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Rand_al%27Thor/Chronology#The_Gathering_Storm ↩

- The Gathering Storm/Chapter 50. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 14, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/The_Gathering_Storm/Chapter_50 ↩

- to, C. (2023). Rand al’Thor/Chronology. A Wheel of Time Wiki; Fandom, Inc. https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Rand_al%27Thor/Chronology#Final_pieces_to_his_army ↩

- A Crown of Swords/Chapter 37. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/A_Crown_of_Swords/Chapter_37 ↩

- JulesIllu. (2022, January 21). Mat and Tuon playing stones together:). https://www.reddit.com/r/WoT/comments/s98fto/mat_and_tuon_playing_stones_together/ ↩

- Mat Cauthon. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Mat_Cauthon ↩

- Perrin Aybara by Manweri on DeviantArt. (2017, August 10). Www.deviantart.com. https://www.deviantart.com/manweri/art/Perrin-Aybara-698038026 ↩

- Perrin Aybara. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Perrin_Aybara ↩

- Marriage customs. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Marriage_customs#Atha ↩

- (n.d.). Nynaeve al’Meara [Review of Nynaeve al’Meara]. A Wheel of Time Wiki; Fandom Wiki, Inc. Retrieved May 15, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Nynaeve_al’Meara?so=search ↩

- to, C. (2023). Egwene al’Vere. A Wheel of Time Wiki; Fandom, Inc. https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Egwene_al%27Vere ↩

- Elayne Trakand. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Elayne_Trakand?so=search ↩

- Algarin Pendaloan. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Algarin_Pendaloan ↩

- Pillow friends. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Pillow_friends ↩

- to, C. (2023). Winter’s Heart/Chapter 12. A Wheel of Time Wiki; Fandom, Inc. https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Winter%27s_Heart/Chapter_12 ↩

- Min Farshaw, WoT by snowtarg on DeviantArt. (2023, April 8). Www.deviantart.com. https://www.deviantart.com/snowtarg/art/Min-Farshaw-WoT-957098779 ↩

- Min Farshaw. (n.d.). A Wheel of Time Wiki. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://wot.fandom.com/wiki/Min_Farshaw ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Fascinating and thorough, particularly the themes of matriarchy. Nice job!

Thank you! Doing the research on the books was a bit daunting, due to the amount of fine details that are present, but, I’m happy with the end result! I’m glad you enjoyed the read!

I’ve been thinking about reading WoT and I from what heard about the cosmic function of gender in the series, it seemed problematic. It makes perfect sense that a male writer in the 80s, raised with retrograde ideas about gender, but trying to do the right thing in light of the feminist critique of the genre, would stumble a bit. Nice analysis.

Thank you! I would say that the gender roles make sense in the context of the books, and, from my understanding, Jordan actually tried to listen about the aspects he got wrong later on in the series. So, I would say, if you’re thinking about it, give The Eye of the World a try, but have the understanding that it starts slow. Also, I would really have to recommend Daniel Greene’s YouTube channel for a really good, mostly spoiler free synopsis of the whole series that helped me keep track of everything going on.

Why you don’t make girl magic and boy magic in the first place.

The whole premise of the books/show/property is flawed.

It took me ten years to finish the series (college, grad school didn’t give me much time or motivation for fun reading).

Oooooookay. You sold me. I will pick it back up and read the full series. 🙂

I hope you enjoy it!

Who are your favorite characters?

Difficult question! Mat’s always fun to read about when he’s the point of view. Rand is another one of my favorites, though, I definitely loved to hate him until he had certain realizations. I also really like Lan and Nynaeve, as well as Aviendha. I feel like I’m missing a couple more, though. Who are your favorites?

How about favorite scenes, of which I have many. One of them is when Mat addresses Egwene by her full title in Salidar before proceeding to Ebou Dar. It shows the full character of Mats, he is not just a joker who travels around and pranks everyone, he is also a person who takes care of his loved ones. And that’s one of the reasons why he’s my favorite character in the books, he has so many sides. Then he also has the relationship that makes the most sense in the whole series and then I’m not talking about his relationship with Tuon Athaem Kore Paendrag, but his friendship relationship with Birgitte, the two of them together only mean one thing, trouble for someone. Then his relationships with many others such as Thom, Olver and Noal are also absolutely fantastic.

Ooh, tough one! A few that come to mind right away are:

Rand’s reaction to Elayne, Aviendha, and Min confronting him, but definitely not in the way he expected!

Nynaeve breaking her block on saidar

Perrin creating a Power forged weapon

Mat in the whole 13th book

Rand in the end of book 12, both punching that one Forsaken’s manor into the ground AND his resolution on Dragonmount.

I’m sure there are others that I really enjoy but am not thinking of.

Perrin and Faile are my favorite characters! Really enjoyed Perrins slow burn storyline and his personal character development throughout the series…. Lanfear would be a close third. I don’t know if it was intentional on Jordan’s part but there was a lot of tension between her and Rand that I thought was well done (I came close to wishing for her redemption).

In the books, the world is different from ours. The characters feel relatable but come from a different society with unique cultures and gender issues. Men have gone mad and caused destruction, and women have special powers, so their interactions are different. Trust isn’t easy, and there’s a lot of underlying resentment.

Some people might be uncomfortable with the gender dynamics in The Wheel of Time because they think it’s supposed to reflect our society. But it’s not. It’s a fantasy world, as different to us as another country’s gender roles.

I don’t think RJ was reflecting our society’s sexism, but rather putting a twist on it.

It’s pretty clear that the Third Age White Tower is like the Vatican today. They both have people wearing stoles, secret plots, and titles like the Amyrlin Seat vs. the Papal See. Even “Aes Sedai” means “servant” in the Old Tongue, similar to how one of the Pope’s titles is “Servant of the Servants of God.”

In WoT, women are in charge. A woman could show up in town and cause trouble, and everyone has to accept it because only women can stop male channelers.

When they call a man “wool-headed,” it’s like men today saying “men are talking” to women.

I think fantasy opens up lots of possibilities to explore gender (and other stuff) in ways that straight up realist fiction can’t. What frustrates me about about WoT, though, is that while he develops an awesome world with its own unique set of gender dynamics, these dynamics are taken for granted by the characters in such a way that a lot of it plays out in a kind of uniform, samey way.

I think the Breaking has a bigger effect on people’s minds in this world than we realize. Imagine growing up hearing stories about a time long ago when men and women had amazing powers and made a perfect world. Then, you learn that men with those powers destroyed everything, and now only women are trusted with them. That would really change how people see gender compared to our real world.

Gender in the WoT is surely my biggest issue with it, even more so than how he wrote a 6 book series in 15 books.

Makes sense to me, since I know there are some things in there that are not exactly great. While it is pending, I have an upcoming article on the TV show’s adaptation, and, while I didn’t go into detail about the gender roles in that article, I will say that I’m very interested at what the showrunner has done to update some of those elements. I’ll be interested to see where it goes in later seasons, with particular interest in how certain relationships will be portrayed.

The series has thousands of years of baked-in gender bias and distrust in it, thanks to the Breaking of the World.

There’s a lot of “That’s true but I don’t want to admit it” in the series, and a lot of “That’s true if we’re talking about back in my grandfather’s day” in the readership.

I like the gender portrayals in wot.

I think the story is trying to make us understand men better by flipping our usual ideas about gender roles. In our world, men are often seen as strong and stoic while women are seen as nurturing and wise. The books switch this around, making women the leaders and men take on roles that women usually have in our society.

So, interestingly, I believe Robert Jordan had said in an interview something to that effect. Also that miscommunication was a big, purposeful issue throughout the series. Thanks for the comment!

I love the fact that both genders have massive flaws that they don’t seem to realise they have. They all project faults on to the other gender and clearly misunderstand their motivations.

This is well put and RJs ‘gendered’ ideas clicked for me when Perrin went back to the Two Rivers and all the adults talked about relationships and marriage. The idea that men and women see the world through a slightly different colored lens isn’t sexist here, they’re both dealing with a pretty severe handicap that the other can help them with.

I think a character with an interesting arc is Verin Mathwin. Trying to figure out her loyalties and her plans through the books.

Yes! I haven’t been able to give the series a re-read, but my friend is listening to the books for the first time–though it’s like their fourth or fifth time through the series–and listening to the books has really made that foreshadowing apparent! Thanks for the read and the comment.

Absolutely interesting character!

I read one or two WoT books a month until Path of Daggers, at which point I needed to take a break. That was in 2020, and I’ve since started a PhD and haven’t had time to keep going. But I’m going to pick it back up again after reading this article.

That’s impressive! I first encountered the series in high school and was able to read about 100 pages a day back then, but, the middle of the series really dragged along with the plot for me, so, I ended up putting it down until grad school. I will say the rest of the series is worth the read, and I’m glad I encouraged you to keep reading. Good luck with your PhD!

Started reading the series in about 1993. Started re-reading in about 2005 and stopped when Robert Jordan passed away, picking up again when Brandon Sanderson’s books were released.

A very detailed discussion! Always worth engaging with these concepts and exploring them in the depth present here. Thanks for sharing this!

Thank you!

This is one of my favorite series of all time. Re-read them a dozen times. Unfortunately, I was deeply disappointed by the Amazon adaptation.

Rand, Nynaeve, Moraine, Lan and Androl are among my favorite characters and Towers of Midnight is my favorite book, love the Rand scenes in that book.

I have a recommendation for you guys – a podcast called Wheel Takes. Its a husband and wife reading the books and doing one to three chapters per episode. It’s incredibly in depth and super fun. Gus, the husband, has read the whole series and his wife Ali is a first time reader. Interestingly Ali clocked the Thom/Moiraine romance in Book 1!!! They’re into Knife of Dreams now so she still doesn’t know what is going to happen but she’s adamant that Moiraine is alive and that Thom is going to rescue her. So there is foreshadowing hahaha.

Women hold the greatest power – that of the Aes Sedai – but that power is rare and centralized. Everywhere else, men are still physically stronger and larger. Men’s martial prowess still has to be counted in power games that deal with armies and battles, even if some women have the ultimate trump card. I think RJ struck a very interesting balance in that way.

I always thought the magic system is based on sex, not gender. And each soul has an assigned sex that cannot be changed, nor can the assigned potential for the One Power.

What’s the difference between sex and gender.

Sex is exactly what you’d think it is. Determined by genetics and easily visible in people. But even this is a spectrum and not as simple as XX or XY since intersex people (those who have a mix of sex characteristics) also exist. Gender identity is determined in brain which is the person’s internal sense of their own gender identity. Look it up.

The fundamental message of The Wheel Of Time is that the greatest achievements were realized when men and women worked together and in balance. The One Power turns the wheel, and because only women can use the power the balance is disrupted. The Dragon HAS to be male in order to re-achieve balance. By highlighting activism into the writing in the live-action, they broke the wheel.

Nothing in the show contradicts this, though. The dragon IS a male in this age, because the Wheel needs it to be so. It is the Aes Sedai with their 3000 year old translated-multiple-times prophecies that are not sure. The wheel itself is unchanged.

You do realize that the Dragon in the show is still male, right? So what you’re saying makes no sense as a criticism

He does not stand out in the series. He is not different from the people around him. But then the village he comes from does not make any sense in the television series – it is supposed to be a rural village, but it has the racial mix of a modern city. It is true that the arrogance of the original Dragon was a terrible (fatal) weakness – driving away people who could have been allies (driving them to the Shadow) and leading him to ignore vital advice and warnings, but the strength has to be there, the point is for the Dragon Reborn to have learned to not be arrogant (not to have become weak – if he is weak he is of no use in the war).

What’s everything stance on the TV Series adaptation? Particularly in relation to gender discussions.

The lore changes get to me the most. I honestly don’t mind them making the themes more mature and even grittier as in my eyes the series is full of mature and violent content that is just not described in great detail in the books because that isn’t Jordan’s style.

However, the random lore changes and the dumbing down of some of the best themes of the books (ie the tower politics seem like middle school bickering here) are what bothers me the most

I agree. I don’t think the writing is very good. It just doesn’t have the quality you’d expect in something this epic. TLOR is the gold standard for a fantasy adaption IMO, and this series shouldn’t even be mentioned next to that. This series is about as good as the Shannara Chronicles – watchable but forgettable. It’s an awful effort to have such a considerable budget/excellent source material. Hollywood is really struggling to make quality products anymore. They’ve let the political ideology infest everything, and it hurts quality IMO.

As a lover of the books, I feel disrespected by the show. I feel that it’s in the hands of people who either don’t get it, or don’t care. To the point of completely destroying the whole point of Perrin’s character while thinking they’re improving his arc by having him accidentally kill his wife. It’s a travesty in my opinion.

So, I actually have an article that’s currently pending publication on the show adaptation, which definitely helped me understand how and why it happened a lot better. From what I found, it’s a lot less that the developers don’t care, and a lot more that production has a lot of notes for each season. I agree that Perrin having a wife that he just kind of kills in the first episode is not necessarily how I would have brought the main conflict of his character arc in the books a bit more to the forefront on screen, though, it is worth noting that the name of his wife in the show is a nod to the Tinker who dies rather horrifically in front of him in the books. So, I think the show is trying to find the balance, because, as much as they would love to just shoot it scene for scene, they can’t.

The showrunner also originally wanted two 45 minute timeslots for the premier, but got told no by Amazon and COVID also really impacted that first season, in addition to a main character just walking off set the last day of filming for the first season, so, that caused them to have to completely throw out the sword training scenes they planned for the second season, too. Season 3 should be covering The Shadow Rising, and, they did particularly well with Egwene’s capture by the Seanchan in season 2, so, it could be that they’re trying to stick closer to the books in some regards from here on out. I know that, originally, at least, the showrunner wanted to update some of the relationship concepts like pillow friends and had plans for showing the relationship between Rand and his lovers a bit more in terms of what the other women think of each other, if the show gets that far.

Almost every single woman thinks Mat is an idiot, even when he proves them wrong every time. Why?!

The only women who think Mat is an idiot are Egwene, Nynaeve, and Elayne. Egwene eventually gets over it, Nynaeve is stubborn and has a hard time changing her mind, and Elayne, being high nobility, can’t see past his arrogance until later in the series. However, most other women, like Tuon, Aviendha, and Birgitte, recognize his worth as soon as they see proof of it.

Mat’s letter to Elayne was one of the funniest parts in the whole series, so at least we got some laughs from it. Also, most of the women come around in AMOL when Mat acts like Sterling Archer: “What was that? I’m sorry, I can’t hear you over the sound of my own deafening awesomeness.”

Nynaeve reminds me of my mom more than any other character I’ve read. A lot of those interactions others find annoying just make me think, “Yep, that’s real.”

I wonder if it’s a cultural thing from the South, because the things that annoy others or seem untrue to them make sense to me. Even when I don’t agree, it’s usually something I’ve heard someone say, so I get why the character believes it.

At the end of the day, it’s important to remember that one of the main themes of the series is that men and women are at their best when working together. Nothing in the books was written out of anger or bigotry. The author was just trying to highlight the differences between men and women while showing how well they complement each other, like many of the character pairings do.

I have a personal theory that Jordan specifically put women in a position of power over men socially, look how the most powerful kingdoms and empire are run by women, so they are at best passively misandrist while our world is also at best passively misogynist. So to alot of men ive met who tried to critique the series they kinda of miss the point that the microaggressions men face in the book are reflections of the kind that woman face which is why I think this series has always attracted alot of women to read it.

The whole “men broke the world and go crazy” thing was a good logical reason to inject some tension in various points as well as create a society that was recognizably medieval but without falling into just being a clone of England/Europe as so often happens. It didn’t feel arbitrary that women were important and powerful in many of the nations/societies, but it wasn’t blandly egalitarian.

There’s a quote from him where he said he found it interesting that people thought he was writing a matriarchal society when he meant for it to be more equal. Whether he failed at that or if it’s just readers’ interpretations is up for debate.

He definitely tried to reverse some things. In his world, men are responsible for their version of ‘original sin’ or Pandora’s box, not women like in our myths. This changes the dynamics. You also see men and women swapping stereotypes. For example, women in WoT might say men are gossips or too emotional to lead. So, I think some male readers miss the point and might need to look at themselves more closely.

That’s actually a great point. Cheers for that!

It really changed how i viewed the series, originally the female characters made angry as a teenager, but then it made more sense and made me more aware of these issues. By no means was Jordan perfect in that regard but damn if he didnt make alot of young men think.

Imagine if during the Cold War, a large number of men went completely insane—maybe about 1 in 10, including important people like government officials, doctors, and soldiers. Some world leaders go crazy, launch nukes, and invade each other. In the end, the world’s geography changes, most people are dead, and modern technology is mostly gone. All the insane men are either killed or imprisoned by a global group of powerful women. This group continues to deal with men who go insane for the next 3,000 years.

How do you think that would change how women view men, and how men view women?

I’m a guy in my 30s, halfway through book 6. I’ve found that both men and women in the story are written as exaggerated types. They’re not really meant to be for or against one side. Aes Sedai are shown as manipulative because that’s their role, while women are often portrayed as strong leaders. Men, on the other hand, seem like smart idiots—good at one thing, whether it’s being noble or sneaky, but clueless in other areas.

Women often fall in love with men for the traits where the men are weakest. These are all over-the-top character traits. There are some well-written characters, but also badly written ones. I often roll my eyes at the characters, but once I accepted that this is just the writing style, I’ve enjoyed the books more.

The women are so often condescending while simultaneously being out of the loop of what is going on, which is a big recipe for pissing you off about WOT.

The books are about duality – light and dark, male and female etc. But also about the shades of grey that exist in between. It’s sort of exploring binary and non-binary themes at the same time.

Fortunately the series is long enough to do justice to all of that. More than long enough TBH, but that’s a topic for another time.

It’s clear that Jordan wanted his world to have different gender dynamics than usual fantasy worlds (and our world). But often it felt like he was trying too hard, focusing on the negative differences instead of the positive ones. There isn’t much clear development in gender roles, except maybe Androl and Pevara, but I think Sanderson created that part.

Androl and Pevara were definitely a highlight. I wish their relationship had an even bigger role. There was a lot of worry and tension between Asha’man and Aes Sedai, but nothing really resolved it until those two came along.

I like the women in Wot.

I get incredibly frustrated by the way RJ frequently sticks to very – to me – stereotypical gendered stuff in the characterisation of men vs women. Generally speaking. So I tend to roll my eyes a lot, rather than nodding and agreeing with men opining on women or vice versa.

The series itself is very evidently written from a male perspective and most of the female characters are not written well and aren’t dimensional. As much as I love the series, the gender issues are very transparent.

Trying to portrayed some role model as women is very progressive for the time he grew up in, he tried his best, not close enough, but getting there

I tend to roll my eyes every time someone is talking about someone of the opposite gender. Whenever Nynaeve goes on about men!, eye roll, and when I read the word bosom 3 times per page in a Mat chapter, another eye roll.

I’ve read the first 10 books 3 or 4 times but never finished the series. Probably the biggest reason for that is I get annoyed reading how the women think the men are arrogant and pushy and the men think the women are manipulative and secretive.

I get that the point is that men and women are stronger together but the gender depictions are too much for me. Half of the series could be cut out if Rand and the rest just communicated instead of assuming.

I find most of the commentary across genders is pretty balanced and comical in the way they view each other.

I find WoT to be a misogynistic world except that some of the women actually have magical power so the men have to grumble secretly. The way to tell is what happens to women without power.

I like some of the women of WoT and others I find are poorly written and obviously written by a man.