Woody Allen’s Nostalgia: Escaping in People, Places and Things

Nostalgia tends to be a tricky feeling. We long for the past as a way to escape the realities of the present. It serves as the perfect reason to watch a film; we transport ourselves to the ideals of another time to forget about what’s bothering us now. It’s a dangerous way of living, for sure, yet the 70s thrived on this way of reminiscing, painting perfect depictions of times that, in the grand scheme, weren’t so long ago, and were altogether not perfect. Woody Allen can be considered one of those filmmakers who has built a steady career off of the nostalgia game. Yet there’s something that sets his films apart from the American Graffitis and the Greases that became so popular with the public. It’s one thing to have actors put on leather jackets and ride thunderbirds around; it’s something altogether more difficult to depict characters who are so crippled by the nostalgia that they attempt to live the escapism; the ideal lifestyle without the issues of life.

Allen understands the illusion of the film image in the fabrication of nostalgic ideals, as he demonstrates in one of his earlier pieces Play It Again, Sam. Film, being deceptive by its nature, is the perfect venue to weed out what would be considered imperfect to depict a divine world, from the persona of a film star to the beauties of the female gender.

Allen’s vehicle is San Franciscan film writer Alan Felix, a man obsessed with the film image. His very career is rooted in the analysis of films from the past, and in fact overflows into his personal life. From the opening scenes his ex-wife has left him mostly for the reason that he is a watcher. She wants to go out and do things, meanwhile Felix would rather go to movies, or more appropriately, just watch life unfold before him. As noted, “the film image can come between ourselves and our experiences,” which is the kind of obstruction Felix has between himself and the realities of the world.

This obsession with the perfect image carries over to Felix’s romanticized ideals over several aspects in his life. With his ex-wife separated from him, Felix and his friends, Dick and Linda, set out to find a rebound girl. The very base idea that the answer to Felix’s problems is a woman sets up this comparison of the woman to the image. Much of film history has seen both genders take on differing roles in respect to the camera; women being the viewed, and man being the viewer.

Felix’s obsession with women is rooted in very high standards. He likes blondes, who are smart and have large busts, and behinds “he can sink his teeth into.” It’s no surprise then that each woman he is set up with or attempts to make a pass at are of supermodel stature. Yet despite these women being perfect in image, many signs point to a break down of those skin-deep ideals. On their blind double date with Dick and Linda, Sharon explains that she was in an art house movie with nine other guys called “Gangbang,” but then goes on to say, in disappointment, that despite the name it was in no way sexy.

His next date is with the self-proclaimed nymphomaniac Jennifer. As she tells Felix that she’s very open about her sexuality and must have it at all hours, she sits next to him with her legs crossed over his lap. She continues to tell him about her sex life until Felix begins to boil until finally he jumps on her for a kiss. She throws her off of him and yells, “what do you take me for??” He leaves muttering “how did I misread those signs?”

When Felix and Linda are touring a museum she remarks how beautiful all the artwork is, to which Felix remarks, “where are the girls?” Shortly after he spots a gorgeous raven haired art type, to which he works up the nerve to talk to her about the Jackson Pollock piece she’s in front of. She goes on to deliver a surprisingly morbid insight on the piece being about “the emptiness of existence; the predicament of man forced to live in a barren godless eternity.” Felix asks her out on a date for Saturday, only to be rejected because she plans to commit suicide that day. Much of Felix’s struggles with women are rooted in his disregard for the reality of their existence, in favor of the beauty they project through their appearances.

Though this is part of the issue, the other side of the problem is that Felix partakes in obsession over his own image. In order to find the perfect woman with the perfect image, he must create and supply his own perfect image. His frantic cluttering of his apartment minutes before Sharon arrives perfectly demonstrates this philosophy. He leaves books open on desks and chairs to imply he’s an avid reader. Linda scoffs at him for leaving a track medal out, to which he responds “why not? I paid 20 dollars for it!” He doesn’t know which music to put on, before Linda tells him to put on one and leave the record sleeve of the other out on a table for Sharon to see. The fact that his apartment is lined wall to wall with Humphrey Bogart movie posters gives us the impression that Felix prefers to be surrounded by a fictional world, and speaks volumes to why he would hallucinate the image of Bogart informing him on how to live his life.

This hallucination, however, is of Bogart the character as opposed to Bogart the person. The answers he provides Felix are sexist tough guy don’t-take-crap-from-no-dame ideals that are obviously fueled by Felix’s underlying perceptions of who Bogart is, instead of who Bogart actually is. Bogart sticks around on his eventual date with Linda, feeding Felix lines to tell Linda that will soften her up to an overdramatic and impulsive kiss, straight from a movie. Despite his reluctance, Felix gives in to these tactics, telling Linda she’s beautiful 20 times, and that she has “the most eyes I’ve ever seen on a person.” It’s the same awkward methods of courtship he attempts on his previous blind dates, to which Linda has asked him why he puts on a false mask every time he meets a girl. It’s a nervous habit spawned from his escaping into the image.

This also creates an expectation within Felix for how the scenarios in his life should play out. There is a drastic difference between the ways he imagines situations to go, and how they will really unfold. It starts with thoughts of what his ex-wife Nancy is doing now that they’re separated. The image cuts to a scene plucked right out of easy rider; Nancy on the back of a motorcycle with a tall, blond haired blue eyed rebel as she explains to him how lame her ex husband was, always being a watcher and never a doer. They then go on to have sex in a field.

Later in the film he runs into Nancy for the first time since their separation, and she’s moving to back to New York on her own, not touring the countryside with Peter Fonda. An early hallucination of Bogart leads Felix to imagine the ending of his date with Sharon, a gorgeous woman who is so astounded with not only how much of a genius he is, but also that he’s quite the animal. He responds with his best Bogart impression telling her that she had to be slapped around a bit. It’s all the more heartbreaking when at the end of his real date with Sharon, he follows her up to her door, and in attempting his Bogart impression, has the door slammed in his face.

When he finally sets up a pseudo date with Linda, he keeps talking about what he’s going to do to prepare, but ultimately keeps imagining the same shot over and over of them in a overdramatic kissing pose, a guitar at his waste, champagne on the rug in front of a crackling fire. When Felix and Linda finally do have their kiss, it’s intercut with images of Bogart kissing Bergman, though this takes all the drama out of the kiss as we interpret it as if Felix is imagining Bogart’s kiss in his head, which completely dwarfs his kiss with Linda.

When Felix decides that he needs to tell Dick that he slept with his wife Linda, he begins to oversimplify Dick’s reactions through various film trope scenarios. First there’s the sophisticated adult response, as we see Dick and Felix sitting in armoire chairs smoking pipes and wearing monocles. Felix tells Dick, to which Dick is ecstatically in favor, for his doctor has told him he has two months to live. Next there’s the melancholy Dick, who is so broken up over his best friend and his wife sleeping together; the two people he loves have hurt him so much that he decides to walk into the ocean naked until he drowns. Then there’s the irrationally vengeful Dick, a scene stolen right out of an Italian film in which Dick and Felix are in the back of a delicatessen and Dick stabs Felix with a butcher knife. The fact that Felix only rationalizes these turns of events through movie scenes implies that he cannot cope with real life issues on any realistic or complex level, a common theme in most nostalgia movies.

Felix’s ultimate issue, having to break off his romantic triangle with Linda, serves as the ultimate example of how consumed Felix is by the image of film. PIAS works with visual bookends that mirror each other; in the opening scene, Felix is watching the final sequence of Casablanca, in which Bogart gives up Bergman to another man for the greater good. The final scene is set up and executed in the exact same way. The plot has brought us to the San Francisco airport; Felix is playing the Bogart character by handing over Linda to Dick, because it’s the right thing to do; even the lines are ripped straight from Casablanca. Felix says “if that plane leaves the ground and you’re not with him, you’ll regret it. Maybe not today. Maybe not tomorrow, but soon and for the rest of your life.” Linda finds it beautiful, to which Felix says “it’s from Casablanca. I’ve been waiting my whole life to say it.”

The major difference between Bogart’s ending and Felix’s ending is that Felix is left on his own to whether the fog of the airport. This is a brilliant visualization of Felix’s character development, showing a true sign of progression towards reality from imagery. By not being with Linda, Felix isn’t bogged down by the image of the past, but by not having anyone to accompany him through, he isn’t tempted by the images of a new person, and therefore he’s able to really cope with his breakup with his ex-wife. There’s no new girl to chase, which implies that he no longer needs the promise of a woman to solve his problems.

Some of the most powerful nostalgia, however, manifests itself through a person we have an intimate connection with. It’s no surprise that Allen’s crown jewel, Annie Hall, focuses in on this type of nostalgia, one that any person can relate based on the sole fact that recollecting a human connection is a universal phenomenon. For someone who is constantly living in the past, as main character Alvy has, a past love so vibrant and living as Annie can leave a dramatic imprint on a life. Annie Hall works as a personal and self-reflective insight on Alvy’s past, centering distinctively on Annie.

So to set the overall context for this to work, it is established that Alvy is constantly focus backwards. The film does a great job with its language to this extent, setting up a non-linear narrative structure and having Alvy constantly breaking the 4th wall. This implies that many scenes are memories for Alvy. We visit his childhood in many scenes, most notably in the first segment when he as an adult is sitting in his first grade desk, arguing with the teacher over his lack of latency period in noticing girls. Despite many people telling him he exaggerates bits from his childhood, he proclaims he literally grew up under the Coney Island roller coaster. We aren’t shown Alvy first officially meeting Annie until after their bitter date to the movies to see “The Sorrow and the Pity,” a documentary about Jews and Germans focused on the past for the purpose of making the viewer feel guilty. Annie has commented on Alvy never wanting to try new things, and even going so far as to say that he likes “the same type of New Yorker….you married two of them.”

Against this static main character, Annie’s progressive traits stand out very prominently. She’s an actress from a small town in Wisconsin, who’s poised to progress. We’re introduced to a scene in which she looks back on her past lovers (with Alvy appropriately at her side). They play spectators as her former self flirts with an actor who’s so consumed in the art of acting, and asks her to “touch my heart with your foot.” Though unlike Alvy, who tends to look back on his past with critiques that are soaked in regret, Annie defends her past self’s choices of men, saying he was a good actor and very emotional, then telling Alvy “I don’t think you like emotion too much.” Annie is able to be in touch with her emotions, able to progress from happy to sad to anger without much difficulty. We see this in many scenes between her and Alvy, yet Alvy is never able to reciprocate her feelings. When Annie asks Alvy if he loves her, he’s not able to say “I love you,” in any direct manner, but instead resorts to a joke on the word “love,” not being enough letters. When she breaks down crying after Alvy kills a spider for her, he jokingly asks her if she wanted to have the spider rehabilitated, not thinking initially that it could be about her being so lonely after their break up.

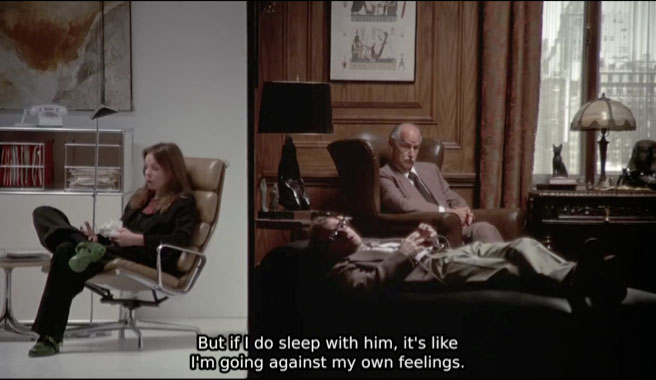

The most telling scene of their polarity is that of the therapist split screen. As a set up, Alvy has been seeing a shrink for 15 years, and has gotten little progress. Annie has started seeing a therapist since dating Alvy, yet her results have been quite extraordinary, and we can see it in the mise en scene of this particular shot. On one side we have Alvy, lying down to represent his regression, surrounded by traditional art of the past in dim lighting. On the other, we see Annie, sitting up right, in a brightly lit room surrounded by modern art. Alvy tells his shrink “she’s making progress and I’m getting screwed.” Meanwhile, Annie tells her therapist “If I go to bed with him, I’m going against my feelings,” a line that blatantly pits Alvy against feelings.

If the scenes of her relationship with Alvy were pieced chronologically, the bookends of their relationship, and in turn her development as a person, can be seen her two singing performances. Her first performance is amongst a restless crowd, singing into a taped up microphone as plates and glassware break throughout her performance. Her next performance gives her better lighting and a more respectful crowd, among which a Los Angeles based record executive offers her an opportunity to cut a record in California, marking her next destination for stardom. Even something as polar opposite as the major cities of the coasts represent the polarities in Alvy and Annie. Annie’s attractions and her eventual move to California speak volumes to her eagerness to move forward with her life, and she points out Alvy’s stasis by comparing him to Manhattan, as “being an island…a dying city.”

These two components, a stasis Alvy and a progressive Annie, are important to remember in terms of what Annie truly does for Alvy. Her main function, in regards to the film, is to provide Alvy with a fond memory for which he never wants to leave. This is an example of nostalgia at its finest. In “Loser Take All,” Maurice Yacowar describes that “only in art can one have such complete and satisfying control over one’s situation.” This can be seen towards the end of the film, after Alvy has had a confrontational discussion with Annie in LA that he wants her back, and she just doesn’t love him in the same way anymore. We see the exact same scene played out verbatim between two broadway actors in a room as they read from scripts, with the only difference being that they end up together. Alvy, in a defensive tone, remarks, “it was my first play…you know how you’re always trying to get things to come out perfect in art, because it’s real difficult in life.”

Alvy is consistently making these attempts at reducing life to art, as we’ve seen in his comedic responses to Annie’s emotions, or constantly escaping to movies to avoid his problems, such as his deteriorating relationship with Annie. Much of this can be attributed to his fear of death, which implies a fear of life. The first book he ever buys Annie, entitled “The Denial of Death,” sparks the conversation that he’s constantly thinking about death. This leaves him in a limbo between thinking about the past and thinking about death, and therefore neglecting life. Annie accuses Alvy of never enjoying life, as she boasts about how in California she meets and enjoys people, and goes to parties. Yet this is what made their relationship work so well, and just as well points to their eventual downfall. Alvy needs Annie to be his life, because he has no sense of what life really is. As Yacowar states, “man’s essential activities are a response to his sense of his inevitable death,” and Alvy uses “art as a means of man’s helplessness before time, loss and death.”

Yet Annie works as life does, a moment in time that is so elusive, and yet will forever be a memory for Alvy. The beginning of the film sets Alvy up to put everything together into some rational thought for which to hold onto, and by the end he comes to the conclusion that Annie is a part of life that he’s thankful that has existed for him, despite being unable to hold onto her forever, as art would do for immortality. Annie is the romantic solution to Alvy’s anxieties of death. All of this is more or less how we approach our own moments of nostalgia. In the holding of nostalgic memories we yearn for a time, a place, or a person that we were so vividly intimate with that ceases to exist in the tangible world.

A similar static character can be seen in Allen’s final work of the 70s, Manhattan, only in this particular instance the crippling nostalgia resonates in the setting that surrounds these particular characters. It is the backdrop of New York that both represent Isaac’s pre conceived notions on society as a whole both in romanticized image and reality. New York is the indirect source of Isaac’s escapism in deluding himself into a life that is ethical and perfect, and yet it is New York from the perspective of the viewer that sobers us to this grandiose expectation.

The opening scene works as an overture to our main character and his relationship to the city, and by association those around him. A beautiful establishing shot of Manhattan’s skyline is met with Isaac’s voice over as he starts in on the opening lines of his book. He first speaks of his main character as he “idolized it all out of proportion,” then later choosing to “romanticize it all out of proportion,” then romanticizing the city too much until finally scrapping the entire structure for another beginning that preaches New York being a metaphor for decaying culture. Feeling this to be too preachy or angry, he finally decides on opening with a line concerning his main character’s sexual prowess being of a jungle cat, to which he keeps with conviction. He ends with the line “New York was his town, and it always would be.”

Throughout this discovery for the perfect line to open his novel, the montage of the city has progressed from large scale establishing shots, so pristine and beautiful, to closer, intimate shots of construction sites and garbage overflowing the streets. This is where we’re introduced to a disregard of detail for the sake of keeping the perfect image in tact, as in this instance, Isaac perceptions of the city and its people. With nostalgia, we tend to lose sight of those specific events in favor of the general experience. Part of why nostalgia films were becoming so popular during the 70s was their blanketing effect over the issues of the 50’s and 60’s. This type of film tended to hide the Cuban Missile Crisis or the McCarthy era of government with Thunderbirds and greasers. In Manhattan, Isaac is committing the same type of cover up with New York as the divine fabricated structure for which he can protect himself from the complexities of real life.

This speaks volumes to Isaac’s difficulties with details on a number of levels. His inability to accept the complexities that come with imperfection causes him to stereotype those around him into over simplification. He complains to Tracy that Mary, based on one encounter, is the existential type that “sit on the floor and eat wine and cheese and mispronounce words like ‘allegorical.’” He is constantly obsessed with the age gap between him and his 17 year old lover Tracy, never once taking her seriously because of her age, despite her being wise way beyond both her years and his. He warns Mary on being too cerebral; that she relies too heavily on the brain, even going as far as to say “greater truths are told by the heart and the senses than by the mind.” This philosophy is put to extreme tests against his friends, both Mary and Yale, who come to him with all sorts of problems in their love triangle that Isaac believes to be “neurotic problems…that keep them from dealing with more unsolvable, terrifying problems of the universe.”

Where Mary and Yale rationalize every bit of their adulterous relationship, the second it affects Isaac, as in Mary confesses that she’s still in love with Yale and seeing him behind Isaac’s back, he accuses both of them for rationalizing everything beyond the need for personal integrity. He goes on to compare himself to the Neanderthal skeleton standing next to him as he tells Yale “I’ll be hanging in a classroom one day, and I wanna make sure when I thin out that I’m well thought of.” He takes a similar offense to the amount of energy his ex-wife has put in to micro analyzing their relationship. His issues with his ex-wife’s tell all book on their controversial marriage are not so much about the validity of the events that transpired, but just in the fact that it will be collected together and presented for everyone to know about in excruciating detail. He begs her to not have the book printed, yet all she’s concerned about is having an accurate and honest depiction of their time together. His friends Yale and Emily read off many harsh descriptions of Isaac, most notably “longed to be an artist, but balked at the necessary sacrifices.”

This particular blurb from her book is all too appropriate when we remember from the beginning of the film Yale’s line on the purpose of art. In Elaine’s, Yale explains that art helps people to experience emotions and feelings that they otherwise wouldn’t. Isaac frustrations with emotional expression are manifested through a parade of narcissistic jokes. Anytime he’s met with an emotional moment, he attempts to puncture the tension through comedy. Tracy attempts to have mature conversations about their relationship, yet Isaac can’t help but refer back to her age through jokes about being able to beat up her dad. When using the example of saving someone from drowning to illustrate that courage is more valuable than talent, he quips “I never have to worry about it because I can’t swim.”

This very struggle internally projects itself into many aspects of the world around him. If he can’t cope with the change in emotions that he has himself, how can we expect him to cope with the changes of the outside world? His expectations of the world around him are not only at unreachable levels, but remain static and uncompromising. As noted before, Manhattan is peppered with shots of construction sites and garbage lining the streets, a visual metaphor for getting rid of the old in exchange for the new. This goes heavily against Isaac’s black and white, George Gershwin scored New York, as we see when he and Mary walk the streets and notice an older building being torn down. Mary asks if it can be recognized as a landmark, to which Isaac responds in defeat “this city’s changing.” His feelings towards marriage are similarly unrealistic, as he comments to Emily when she tells him she knows about Yale’s affair. Isaac is astounded to find that Emily is not furious with the idea. “Marriage requires compromises,” to which Isaac flat out disagrees. He begins to tell her his notions of how marriage should be, before remarking that he’s living in the past. He has a similar conversation with Tracy on the concept of relationships, in that people should be like pigeons and have only one mate. Tracy differs, saying that life could be about having a string of really intimate, yet short, relationships, but Isaac instantly writes off her opinion with another joke about her young age.

Even his decision to come back to Tracy in the end is deeply motivated by his uncompromised ideals. After his fall out with Yale over having any personal integrity, Isaac begins to reflect on why people can’t look past the miniscule in pursuit of the larger problems. This leads him to the generic statement that life is worth living, and he begins to list off the reasons. Though instead of anything personal to him, he acknowledges great works of art from the past, e.g. Marlon Brando, Louis Armstrong, and “those pears and apples Cezanne did.”

These are examples of transcending people and works in their respective mediums, and are only seen as such in the eyes of someone who overlooks the specifics as much as Isaac does. When he runs to meet her before she takes off for London, he tells her how stupid he was for leaving in the first place and begs her not to go, that 6 months in another city can change someone through the experiences they have and who they meet. The thought of this threatens Isaac, appropriately, and when he begs her, she tells him that this is normal, even saying “everyone gets corrupted.” Isaac has never experienced this corruption. His life is still in black and white, and still swinging to the tunes of George Gershwin, in which the movie is littered with mini montages of Isaac experiencing the city to his music.

No example is more clear and direct in symbolism than Isaac’s issues with the tap water at his new, cramped apartment. When he offers people New York tap water, he warns them by complaining that the water is brown. When he offers the water to Mary however, Mary still drinks it despite acknowledging that it’s dirty. Just as well, we as the viewer can’t tell whether the water is dirty or not due to the black and white cinematography. If Isaac hadn’t said anything about the water, we would assume that the water was clean. This perfectly sums up how nostalgia functions. The black and white of the picture, an oversimplification tied to the past, doesn’t allow us to see the details in a clear way. All we observe is a glass of water, not that it’s riddled with bacteria and grime. Just as well, the fact that the water is straight from New York, and is considered dirty, ultimately provides this idea that the city, although seen in a nostalgic light, has its flaws as well. Mary may be able to agree with Isaac that the water is dirty, but unlike Isaac, she’s able to drink it, to take part in its culture and metamorphosis in ways that Isaac cannot due to his high standards in how New York should be based on what it was before.

Notes:

Diane Keaton plays the leading lady in all three of these films, to which she and Allen travel along similar character arcs in terms of their relationships throughout the three films analyzed. Many scenes even refer back to the previous films, such as visual matches in the mise en scene between films.

The title Play it Again, Sam is a reference to a line that is never actually said in the original movie Casablanca, despite its popularity. Even this speaks volumes to how the role of film in pop culture is often manipulated to serve a function in the present.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I first saw PIAS on the big screen; it was about 17 years before I saw it again on cable. I didn’t enjoy it as much the second time around but it brought back a lot of memories! Our family has many DVD’s and premium cable and we STILL complain that we have “nothing to watch.” Some of the DVD’s on our shelves haven’t been opened. Growing up, we only had the 3 networks on TV and I saw many good movies on the late, late show!

Great writeup! I am a lifelong Woody Allen fan!

Woody Allen is the Oscar Wilde of my generation. End of story.

What is your generation, if I may ask?

Mr Allen is a genius writer/director/film maker. I will continue to enjoy his films because I choose to separate the flawed man from the movie maker. Like I do with many of my favorites. Was Keith Richards a great father and model citizen? Was Picasso an honest, devoted husband? The examples are as long as history itself. Artists, like humans are, well, human. And often the most flawed and broken among us. I’m not excusing his sins, just choosing to compartmentalize them from his art. If you choose not to, that’s your business. But you’ll be poorer for that choice.

I couldn’t agree more, and this is exactly my approach. It’s good to see I have some companions in the same boat.

Play It Again, Sam is a hilarious movie. It is one of the funniest movies i have ever seen, with mountains of quotable lines (my favorite being “i was no where near oakland”) this is a great, great movie

I agree with you, this is by far Woody Allens funniest movie. Bananas was funny, and reconstructing Harry was also very funny, but this is by far the best of his comedy movies.

I especially like the scene right after his wife dumped him, where he has this vision of his wife driving on the back of a motorcycle with a tall blond man, and he cries out: “We’we been divorced two weeks and shes dating a Nazi”.

Or when he is trying to impress the date who comes over by the remark: ” I like the rain, it washes memories of the sidewalk of life” why don’t they write comedy like that anymore.

So many more great moments in this movie….

Great write up. I like you extensive write up of the female roles in Allen’s movies. Woody Allen’s character tends to be the same from movie to movie, but I like the female leads he chooses to play off of.

Great job on your article. I don’t particularly enjoy Woody Allen, but your article kept my interest. I look forward to your next article.

Great in-depth analysis…what are your thoughts on Allen’s more recent films like Midnight in Paris, To Rome with Love, Blue Jasmine, or Magic in the Moonlight?

Most Woody Allen films are semi-autobiographic.

Both are great films.

I understand that many people love Annie Hall. Many consider it his best picture. As pure comedy goes though, PIAS is just so much funnier. All of his earlier films really are. I do enjoy Annie Hall and I understand it has a little more of a plot, but I enjoy this just a little more. It is definitely sillier, but not as silly as some of his other early efforts. This one seems to have a little bit more of a balance. Very funny and enjoyable picture.

Play it again is one of his best and a personal favorite of mine but i wonder why he didn’t direct it not that it could have been any better, maybe the studio heads wanted a well respected director and Herbert Ross certainly is that

I worked 4 months with Woody on SWEET & LOWDOWN – a very special time I’ll always remember. Everyday.

A living legend. Would love to have a chat with him over a coffee.

A most enlightening article. I love Woody Allen.

I really like Play It Again Sam, my fave of Woody’s along with Take The Money, but the gag that powers it is dated. And that’s Dick giving multiple phone no.s because he’s constantly at different addresses. Cell phones have made this gag ancient. “If you need me I’ll be at Frozen Tundra 6”.

I always thought of him as a great talent…I saw Annie Hall ten times through the years and still laugh.

Woody hasn’t made a good film in YEARS.

Woody Allen made classics. Although he hasn’t made great films recently, he was a trademark of the past film industry.

Thanks for sharing. that was interesting and informative. as a person, Woody is still a truncated version of a good or decent person. as an auteur, he makes films that are quite enjoyable.

To me he is the funniest man around.

I think the common sentiment that Allen’s golden era (the late 70’s and 80’s) is long over. The the nostalgia he possessed then seems to have transformed into something more bitter; like an old man grumbling about the way things “used to be”.

His movies have been a great source of distraction in my life and has sparked a fancy for the simple entertainment of our beautiful everyday life.

Man, I would LOVE to see Woody put together a Bob Hope biopic!

I’ve always had a fondness for many of Woody Allen’s films, but never thought so much about the inherent nostalgia his characters engage with–interesting take on his work. Overall, though, I think the greatest strength of Allen’s project is taking these taboos and difficult characters and inflecting how these things are human too. One could suppose that Allen’s life is sort of an example of this too.

Nice analysis. Personally, I love Allen’s films. It is worth going into–as you allude–how important Diane Keaton’s roles in these films are as well. Those two were so dynamic together on screen.

Looking back has always been of interest to me. As we recount, compare and contrast the thens and nows of our lives I also wonder about the hows and the whys. What has really changed versus what seems to have changed? Are the thens of our lives what actually happened or are they re-created personalized interpretations, and who is the arbiter for making those comparisons and conclusions? There would certainly be more than one opinion. What formulae or algorithm should be used to interpret the then and now of our lives so we can determine what has changed – not changed or determine if now is better or worse. Perhaps what may be most important is to consider how the thens of our lives have changed who we are – now.

But if we consider for a moment that things (have) changed, why have they changed? Has a subtle cosmic force been at work to change now from then. Or perhaps “now” is the result of subtle shifts in each generation’s DNA which sets different priorities in each generation that brought us to now. Or is our now simply the result of random acts by billions of people clustered on one planet who are exposed to greater communication and with a more embolden sense of free spirit that serves to lead us beyond previously held acceptable threshold for behavior.

As generation’s inevitably make then and now comparisons, it is easy to become victims – innocent objects compared to when others lived – then what seemed to be better times. On balance are we better now or less so – or are things no better or worse, just different. If we feel insecure now, is being secure always better? If we feel challenged now, is being challenged an inevitable route to something worse?

It seems we have a tendency to think back at ”then” with fondness but while looking forward we feel uneasy and worried as we live in the “now”? There may be no better indication of this when we sense our emotions while viewing a Normal Rockwell or Currier and Ives poster. I think this is because we simply survived the “thens” of our lives and we know how it all turned out leaving us to think those days were safer, more manageable, and less threatening? In contrast, as we look forward, maybe we absorb and internalize the uncertainties we see in our future and use them to create the now of our lives. In so doing, those future uncertainties become our present – our now, so now almost never becomes safer, or better than – then.

Our planet has certainly seen chaos. Human history is full of catastrophic events that impacted people in the worse ways imaginable. Yet my view is the most basic good and evil elements that are embedded in our human nature seem constant as we survive – with the good consistently holding a slight but critical majority within each new generation, and that has brought us all to now with quantities of love, security, emotional growth, wisdom, and companionship.

If there is a rational and concrete thought I can take from considering the thens versus nows of our lives, it might be to understand such comparisons of then and now is folly and the best I can do is avoid making conclusions, enjoy my fond memories of then, learn and gain wisdom from what I have experienced, leave the future for the future, and be the best I can be for now.

Steve Hiss

Thanks for this enjoyable romp through two of my favorite Woody Allen movies. Strange fact: It’s now been 42 years since Play It Again, Sam was released. When the movie was made it was only 29 years since Casablanca came out. Anyway, I like your analysis of how nostalgia works in these films.

This article is very well-written and enjoyable to read. But, taking a look at the “bigger picture”, Hollywood has not veered far from nostalgia in more modern films and what’s even more is the way in which media as a whole uses images, clips and full works to build nostalgia in viewers. Nostalgia is, I believe at the core of the entertainment business– films are made and watched for nostalgic purposes, though most aren’t as aptly centered on the concept as Woody Allen’s films. A great example is the way networks play Christmas movies from the start of November through well-after Christmas each year. Why do you think they play these films and specials over and over and why do you think consumers love every minute of it? Because it brings us back, it allows nostalgic emotions to rise to the surface as we watch an old childhood favorite and reminisce on how wonderful (or not-so-wonderful) Christmas-time was for us as a child. What’s even more is TBS’s monopoly of A Christmas Story, played for 24-hours straight each Christmas day– a film that is narrated by the grown protagonist as he thinks back nostalgically to the “best Christmas ever”. Besides being a nostalgic film in it’s own right, TBS has made it a tradition steeped in nostalgia. My point is this, Woody Allen was merely capitalizing on an emotion felt throughout time, by all. His works were innovative undoubtedly, but not so far-fetched in the grand scheme of things.

Thanks for the feedback! I agree that film is inherently a tool for nostalgia; the fact that we’re watching something that has already happened in the past will never allow film to NOT be nostalgic. Mostly what I’m fascinated with though, in terms of Woody Allen, is that his films, these three in particular, deal with characters who are just as much taken in by the nostalgia effect as we are as viewers. It would be like making a film about someone who absolutely loves “A Christmas Story” and its ideals on Christmas and wanting that specific way Christmas is depicted to be how Christmas should be all the time for everyone. It’s the meta aspects of Woody Allen that gives the nostalgia a slight twist, because his main characters are case studies in what it looks like to be caught up in that nostalgia, either through film or a person or a place, in their everyday lives. It’s a brilliant variation on the feeling because we can look at Alvy, Isaac or Felix and go “oh, I remember when I was absolutely obsessed with (insert person, place or thing), just like Alvy/Isaac/Felix!” except Allen’s characters are crippled by the nostalgia to a fault, which delivers the commentary on what nostalgia can do to us, living so presently in the past.

(Kudos on the Christmas Story example, the nostalgia for that movie and how it’s made a cultural impact through those 24 hour marathons is in itself an awesome multi layer nostalgia pudding that works on so many levels. I mean, I long for a movie that longs for a past, in turn reminding me of my past that involved watching the movie. Those are some incredibly complicated emotions, and they’re happening simultaneously while the Parker family watches a dead duck get decapitated. It’s brilliant.)

Amazing article! I will always be a huge fan of Woody Allen! I think this theme of escaping into the past can also be seen in some of his more recent films as well. In Midnight in Paris, Owen Wilson’s character literally escapes into the past, the 1920’s, because he believes it was a more productive time period. Similarly in Blue Jasmine, Cate Blanchett’s character is so traumatized that she can’t handle her present circumstances, and can only be satisfied by reliving the memories of her luxurious marriage.

It’s refreshing to read something about Woody Allen’s work that’s so positive and insightful. Well done. One thing I’ve noticed in recent years is that part of Allen’s penchant for nostalgia is that he continues to occasionally make what once were called “B Movies” – that is, light confections meant simply to entertain and divert. They’re not of lesser quality, but merely more modest in intention. Unfortunately, many critics and film goers are confused by the fact that he’s making B films with A-list stars. That’s why a frequent complaint is that his recent films aren’t as “profound” as some of his earlier ones. Movies like Magic In The Moonlight aren’t meant, to quote Allen, “to start any new religions.” They’re just smart, fun, and attractive to look at. Nothing wrong with that.

Nostalgia plays out well in his movie Radio Days (1987). This was a good essay, I always felt that watching a Woody Allen movie required two things: 1) a New York City background (which I have, since so much seems to involve New York life), and; 2) a feel for how he weaves nostalgia through his movies.