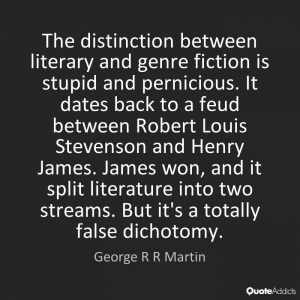

Genre Fiction in University Writing Programs: No longer the MFA’s Red-headed Stepchild

Every day, aspiring writers fill out the necessary forms, compile a portfolio of their best work and apply to Creative Writing MFA degree programs. Why? Prospective students carry a variety of reasons with them to the admissions office, but most share many of the same anticipations. A large percent pursue the degree in order to become teachers and publish their own work on the side. A larger percent hope to become best-selling authors with ample royalty checks. Some hope simply to improve their craft in a community of other writers, but only the smallest portion of would-be MFA graduates endeavors to write literary masterpieces that win the Pulitzer Prize. More and more students in their first semesters are realizing that what the academic environment they’ve plunged themselves into requests of them is exactly what the fewest of them strive for. The intellectual universe is often hostile toward the idea of writing work that sells, which is ultimately counterproductive to encouraging our society to value literature.

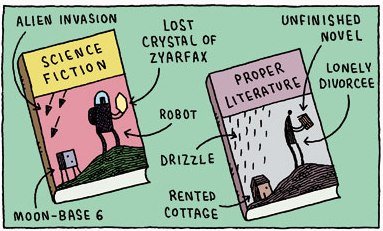

The majority of serious, unpublished writers are also readers, and the majority of those readers are fans of commercial and mainstream fiction. Day after day, a new MFA student steps into the classroom forced to digest the fact that they will not be allowed to write or study the genres they favor. Instead, they will be encouraged to write literary fiction, which they should hope will be published in a small journal read mostly by educated scholars, students, (proud parents of students) and professors. They will be steered away from the general publishing industry, taught that money-making novels that appeal to the masses are poison to intellectualism, and that “success” as a writer means life as a pauper paid only in copies, as Elizabeth Clementson states back in 2005, “My experience in publishing had taught me that writing literary fiction did not lead to great financial wealth.”

These attitudes can best be summed up by a declaration made by revered Iowa Writer’s Workshop alum and Pulitzer Prize-winner, Flannery O’Conner, when she said, “Many a best-seller could have been prevented by a good teacher.” Teachers and students alike eventually adhere to this philosophy, regarding work that the reading public adores as valueless dribble, and blatantly exclude a vast (and highly lucrative) world of writing from academia, altogether. Those students who began as genre fiction writers adapt to their new habitat, turning out manuscripts that reflect not creative originality, but a suffocated, robotic regurgitation of the purist form and function professors dictate as the standard. Michael Underwood illustrates the plight of the aspiring commercial author when he says, “for most MFA programs, genre fiction is at best an also-ran, at worst an outcast forbidden style.”

Students are often turned off by these stigmas and discouraged from study because they feel an MFA would serve as a writing prison rather than a learning experience. Whatever dreams of book deals that might have made their tales a household name or motion picture are lost in the perpetual aim for literary awards and high-brow recognition. For all these reasons, writers who are influenced by and inclined to produce commercial work have found no suitable intellectual environment in which to study this particular medium, until recently.

Genre U

A fairly new concept is being introduced into universities across the nation that has been both attacked and praised for its potential to revolutionize the purpose of the writing program. Several institutions have adopted a commercial and mainstream fiction concentration within their curriculum. Schools like the University of Southern Maine established the Stonecoast MFA back in 2002, which has “ranked in the top ten low-residency programs by Poets&Writers since 2010, and is known for providing a superb, open-minded, and progressive education in the art of writing” (“The Stonecoast Difference”). And Seton Hill University offers a Master of Arts in Writing Popular Fiction, “if you seek real-world success for your creative work” (setonhill.edu qtd in Troilee).

Students are now able to find a niche among their peers and learn an area of specialization that suits them. Instead of being trapped in a vacuum of constantly reappearing dead authors and forced to utilize an increasingly narrow set of literary elements, students can survey a variety of contemporary avenues and devices. Many of these tracks include mystery, romance, horror and suspense, and even ask for a portfolio of work that showcases such specialties for the purpose of admission. Some programs also offer additional courses that explore querying, publishing and market trends.

For many, this is a refreshing godsend, a long-awaited release for those who feel incarcerated by the literary canon and repressed by hundred-year-old standards and traditions. For others, it is a virus that threatens prestige and intellectualism, a plague on the academic world that will stain the MFA and render it frivolous. Eve Shelnutt makes this case in her article “Notes From a Cell: Creative Writing Programs in Isolation” when she says, “With writing students aiming to ‘make it’ by publishing first in literary journals before an assault on New York publishers, with new journals serving mainly mundane purposes such as program validation, what happened in many journals was a splitting off of creative writing from intellectual discourse” (6). Shelnutt calls a writing student’s attempt at earning success in the publishing industry an “assault”, and validating a degree program with such publication “mundane.”

The Pot and the Kettle

Many students ask, “What is expected from a graduate of an MFA writing program if not publication?” Should all writing be for the same purpose? Is “intellectual discourse” the heart and soul of telling stories? Many of the institutions that offer these new program concentrations to the aspiring commercial novelist have answered, no. Western Connecticut State University says “research has shown that the imaginative/emotional and rational/logical functions of the brain are interrelated and that real cultivation of intellectual prowess focuses on neither exclusively. The old model of studying writing as exclusively a ‘creative’ or ‘practical’ endeavor is outmoded” and goes on to announce “the first MFA program in writing that offers the aspiring writer training in both creative and practical writing: food for the soul and food for the table” (“MFA Mission”). A new standard is being formed, one that allows the student to write what he wants, not what scholars think he should.

Many MFA faculty members insist that students write literary work which appeals only to an intelligent and educated audience, not mass market that adheres to a “formula”. Most students who apply for the MFA are looking to learn how to write books that sell. These same students are work-shopping each other’s manuscripts, forming a general concordance about what they liked and what they didn’t like. Isn’t this a micro chasm of learning how to please the reading public? Can it be argued that the workshop has become a kind of agency, an editing studio that strives to conform to the tastes of a “marketplace”? After all, literary fiction has its own set formula though there are few who will confess to it. Even now, publishers of literary journals can tell when a manuscript has the voice of a workshop. Most certainly, the pressure on a student to make his work successfully fit this mold is hypocritical to Flannery O’ Connor’s attack on producing fiction that sells well.

Essentially, students are only learning what other students are likely to want to read, hampered only by their tendency to enforce the rules set by their professors, which they are equally likely to break. The value of literary fiction is not to be disputed, but the continuous exclusion of its more accessible counterpart is not only illogical but ungrounded. O’Conner views a best-seller as something to be “prevented”. Does this mean that a devoted teacher who sees her student turn out one of these should be ashamed of herself? It seems that the purpose of writing is not defined by the individual student, but by a uniform consensus gathered by scholars and academics either dead or set in their ways. Jason Sanford shows disdain for the regime in his article, “Who Wears Short Shorts? Micro Stories and MFA Disgust” when he states:

After all, no matter how many new MFA programs open up in this country, they remain a rather incestuous, similar lot. The average MFA professor is white, upper-middle class, and unacquainted with anything other than their little academic life. It is through their particular worldview lens that all MFA. students pass through and hone their skills. Students who don’t match these professors’ ideas of life and writing either don’t get into the programs or get their writings gutted from the inside out.

It is imperative that these negative claims and generalizations about writing programs be combated by promoting the image of an open, objective institution. Bitter declarations like these are damaging to the MFA portrait, but continue to spring up everywhere, from small journals to internet blogs. The time has come to consider a reformation of academic goals that will allow others to view writing programs as more inclusive and less authoritarian.

We are all Genre

Other arguments are that mainstream fiction is empty of substance and requires little discipline to produce, that it is intended primarily to entertain, and therefore not “fine art.” An author’s intentions should not dictate whether his work has artistic value. There is just as much discipline and devotion in obtaining a publishing contract as there is in earning a literary award. If, in fact, a writer wishes to entertain rather than intellectually enrich his readers, there should be a place for him to learn to do so effectively in the university environment his literary peers enjoy. If we can offer the aspiring student of mainstream fiction no intellectual environment in which to improve his craft, how can we expect the mainstream to ever gain in substance?

Evidence exists to prove that the mainstream mindset is already present in the academic world, though rarely, if at all, acknowledged. It is present in the workshop, where students critique manuscripts biased by their general preferences. It is present with the professors and graduates, many of whom hold occupations as editors and agents of mainstream fiction, often advising clients how their work will earn royalties while in the same breath stressing to their graduate students how to rid their literary prose of triteness. Most who are affiliated with these primarily literary programs wind up rooted in the marketplace in one way or another.

The few university writing programs that are embracing the commercial empire as a credible area of study are doing so because it is an everlasting and relevant staple of writing life. The publishing industry and the reading public lurk in academia no matter how hard educators, theorists and intellectuals try to dismiss or remove them. Just as there will always be the literary students who diligently strive for awards, the hopeful romance and science-fiction novelists will also appear in the creative writing classroom. The obvious benefit of a genre-friendly MFA program is that these students can coexist in an environment where they can learn from each other. This also to stress that there should not be segregation between literary and mainstream writing. With schools like Emerson College offering an MFA that focuses primarily on publishing genre work, we may be quickly coming to an over correction. The goal is to explore and study both in order to be a well-rounded writer – not to separate each into a camp of its own.

The responsibility of creative writing teachers must and has already undergone reform in light of these developing modifications. Instructors should no longer be charged with urging students to write award-winning manuscripts, nor should they be obligated to push a student toward producing sellable work. Each writer has an individual goal, and it is simply an instructor’s aim to realize and nurture it, rather than cut it to fit the rigid literary yardstick. Students should have the opportunity to understand the differences between literary and genre fiction, and to make an educated decision about which would fulfill them, even if it’s both. These are the foundations on which the new era of the MFA should be planting its feet.

So, what should students of all types of fiction expect from a Creative Writing MFA program? If the present reform continues, they should hope to have the chance to surround themselves with a more diverse population of students, professors and courses. At the University of Southern Maine, “Many of our faculty write across genres, and we know the richness of inspiration other genres can provide”(“The Stonecoast Philosophy”). Perhaps this philosophy represents the ideal environment for studying writing. A prospective student hoping to engage in a writing degree program can now have a balance of expectations. These schools offer the freedom to explore the legacy of great authors and also what makes up commercial convention. A place where writers can work, study and share with other writers in an atmosphere of variation is the most crucial benefit.

Why the academic world still recoils at the idea of genre fiction in the classroom, despite its effort to explain it, still doesn’t seem to stem from a noble cause. A direct effect of commercial authors studying the craft on the university level is that they will turn out quality popular novels that the masses will intellectually benefit from. Readers would have entertaining fiction that is also quality prose infused with substantive themes and characters, kind of like sneaking nutritional ingredients into a kid’s meal. Isn’t that what we should hope for in a society that has taken a nose dive when it comes to appreciating well-crafted literature? Shouldn’t we strive to use this perfectly excellent platform to medicate the sickness of lazy sentence structure and empty calories in many published works? You can’t complain about the lack of substance when you’re not offering popular fiction authors a welcome environment for mastery. But, perhaps the highbrows would prefer the tastes of the mass reading public to remain substandard. If popular fiction increased in intellectual quality, there would be fewer reasons to look down on it.

It’s been seventy years since the University of Iowa began turning out dozens of prize-winning authors. Since then, it has been the model for writing programs across the nation and has modified its philosophy little, if at all. While the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and other prestigious universities will continue to serve as the stronghold for these literary traditions, one can’t ignore the necessity for the creative writing program to evolve. The time for exclusion is nearly at an end as the publishing mainstream craves newer, fresher, more independent voices. Degree programs should not disregard the chance to be that engine for America’s readership.

Works Cited

Clementson, Elizabeth. “Down with MFAs.” Mobylives.com, Dennis Loy Johnson, 2005, http://www.mobylives.com/anti_MFA.html. Accessed 21 October 2016.

“MFA Mission.” wcsu.edu, Western Connecticut University, 2015, http:// www.wcsu.edu/ writing/mfa/Mission.asp. Accessed 24, September 2016.

Sanford, Jason. “Who Wears Short Shorts? Micro Stories and MFA Disgust.” storysouth.com. storySouth, 2005, http://www.storysouth.com/ fall2004/ shortshorts.html. Accessed 24, September 2016.

Shelnutt, Eve. “Notes from a Cell: Creative Writing Programs in Isolation.” Creative Writing in America: Theory and Pedagogy, Ed. Jospeh M. Moxley, National Council of Teachers, 1989, pp.6

“The Stonecoast Philosophy.” Usm.main.edu, University of Southern Maine, 2016, https://usm.maine.edu/stonecoastmfa/philosophy. Accessed 10 September 2016.

Troilee. “Low Residency MFA [archive].” Absolute Writer Water Cooler. 16 July 2006, http://absolutewrite.com/forums/archive/index.php/t-35571.html. Accessed 28, October 2016.

Underwood, Michael. “The Ultimate Genre MFA.” michealunderwood.com, Geek Theory, 2015, http://michaelrunderwood.com/2015/03/02/the-ultimate-genre-mfa/. Accessed 15 October 2016.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Very interesting article! I’m currently a humble BA in creative writing and had never noticed (or considered) this sort of divide in the curriculum. Certainly in certain professors I’ve had but not in what we had to learn. This is certainly something to watch out for and, as a more “commercial” genre writer in these programs, hopefully something I can work to change.

Thank you for your insight!

The English dept. at my school has a preference for creative non-fiction, that’s where they have their ‘prized’ MFA students, but they host an excellent journal which has a broad range of work.

Sharing this with my colleagues.

Lovely article!

Hmm… Maybe I should start considering this in my college search, ha. I never even knew about this divide, but I love genre fiction and definitely want to write it (perhaps not exclusively, though).

Interesting that this divide doesn’t seem to be present in cinema, where many popular/mainstream works are praised by critics as well-crafted. Spielberg is universally acknowledged as a master, but mainstream audiences still love his movies.

A few months before our Master of Fine Arts program launched, a writer mailed me to inquire about teaching opportunities. But when I explained that our fiction track focused on mainstream and popular genres, she responded, “Oh! I wouldn’t be interested in teaching that!”

This comment served as a reminder of just how wide the gap remains between the so-called “literary” fiction offered by almost all MFA programs, and writing intended for more mainstream audiences.

The gap between the genre fiction crowd and the MFA community hasn’t narrowed as much as it should.

GREAT article. Forward-thinking institutions need to read the market barometers and adjust their tacks.

It looks like writing courses in academia simply has turned their backs to audiences and have began writing for one another.

Writers in MFA programs are only writing to impress other MFA writers.

This is a very current topic and I praise your for treating it so well.

Our university is receptive to genre fiction. I was on a thesis committee for a student who wrote a YA fantasy novel, and on another for a student who wrote a collection of very slipstream-ish, weird short stories.

Thanks wtardieu for compiling this

I loved my MFA program and it made me a better writer for sure, but I also already had three small-press novels published and had a sense of the industry.

Good writing is good writing, regardless of the intended market, and MFAs should be raising the bar—not just for the literary elite but also for expectations by the larger reading public.

Writers should expect to see more varied offerings in coming years.

I use realist/non-realist fiction for a reason: I don’t believe in traditional ideas of division between “literary” and “commercial” fiction, since realist fiction and non-realist fiction can fit either descriptor.

Completely agree with everything. There is still a sense and a perception that unless you’re writing fiction, you’re somehow writing lesser work.

I’ve completed two writing course in the UK and while most other writers on the course haven’t been writers of speculative fiction the tutors have been very encouraging. Similarly a writing course at Lancaster University was also very supportive of my subject.

Evolution and change is necessary – especially when it comes to inclusion of all writers; however, it is the artist that finds their own rewards personally or monetarily. You take the tools that are presented and then you forge your own way. Thank you for presenting this point of view.

Writers should certainly be able to attend graduate programs to improve their work without abandoning hope of succeeding in the popular markets.

I wasn’t completely aware that there was this difference in MFA programs, even though I’ve been pretty close to several graduate students and professors throughout my university experience.

Although I agree that the type of fiction we see being mass produced on bookstore shelves should be the type of creativity taught in college courses, I believe college courses should distinguish between what is acceptable and not acceptable; what I mean by that is, there are plenty of young adult novels that should be thrown backwards into the drafting phase.

I can see why some professors would find pause with the idea of teaching how to become a writer of the caliber of books such as Harry Potter or Percy Jackson – once you take a good long look at them, you realize they’re not that good. There’s a high lack of creativity among authors who write young adult literature such as the Immortal Instruments series which reads like sloppy fan-fiction that should have never hit the shelves; I don’t just say this because of my own personal distaste for the series, but after looking at the novels objectively, they just have too many plot mistakes, poor pacing, and poor character development.

I’d like to see professors taking a serious crack at throwing modern novelization into their course repertoire, but they should take caution not to crank out mediocre writers for the sake of giving them new avenues.

I have done no looking into MFA programs, but I am a recent college grad who majored in creative writing. I wish to be an author and am currently working on a book I would like to publish. I am also an avid fan of fantasy (and to a lesser extent scifi). I have encountered a lot of criticism against genre fiction and how it is “lesser” to “true literature” and so on.

I do agree with a lot of what this article says, and believe me, I am one of the people most in favor of getting rid of these ridiculous distinctions. However, this article still seems (to me anyway) to be setting up a bit of a dichotomy that I disagree with. Now sure, there are some mainstream novels that are of sub par quality. The are (and have been) some mainstream titles that were/are just bad (I’m looking at you 50 shades of gray and twilight). But after reading this, it sounds like the author is still distinguishing between lit and genre fiction, saying that we should be raising genre fiction to the intellectual level of literature (forgive me if I am misrepresenting the article). Especially when analogies likening the genre fiction to a kids meal, and the literature to the vitamins are used.

Also, I got the sense that a dichotomy was set up such that either you write to be an intellectual literary award winner, or you write to sell. Personally, I believe that most writers simply write because they want to, and if they can live off of the writing alone that would be ideal (I know that’s my dream).

Again, I just have to say that I think there is much less difference between so called “literature” and genre fiction. To a large extent, I think it is a meaningless and potentially harmful distinction that only serves to further lend credence to the lit snobs who look down on all us other writers.

But please, do not confuse my ranting with a total dislike of this article. I agree with most of the points raised, and I think only good can come from more open-minded and inclusive MFA programs. And I will not dispute that this article is well written.

So overall I would definitely say this is a very good article, but it did have a few key points I felt were not representative of fiction. And if I read too much into this and misrepresented the article I do apologize. But the bottom line is I feel like it is still (unintentionally or not) making distinctions between literature and genre fiction that I think are unfair.

I’m not suggesting we raise genre fiction to the intellectual level of literature, I’m suggesting that universities stop using the category to predetermine the intellectual level of a work. The kid’s meal analogy wasn’t meant to denigrate genre fiction. I certainly wasn’t my intention to unfairly represent the mainstream. It was my intention, though, to appeal to the opposing audience by acknowledging their perceptions of it. Thanks so much for your feedback, and I wish you the best of luck with your book.

And thank you for clearing that up. I am used to genre fiction getting the raw treatment, and do apologize if I read to much into things (distinctly possible). But yeah, overall it’s great that the gap is lessening between the two.

Awesome article! Articulated a problem that’s been plaguing writing programs for year. I especially like the point of teachers not urging one way or the other, not forcing students to choose between academic acclaim or popular success. Honestly, the two aren’t always mutually exclusive. Look at works like “Catcher on the Rye”, “The Great Gatsby”, and “The Lord of the Rings”. All technically genre books intended for entertainment, all enjoyed commercial success, and yet all rich in intellectual rich. They leave something for the scholar and the civilian, proving that being literary and genre aren’t always separate entities.

Great article.

I think the literary aficionado’s understanding of genre fiction is as equally misconceived and erroneous as the mainstream’s disdain for “Literary fiction.” Both perceive the others as wrong in a way. Lit Fic is snobby and pointless, Genre Fic is mundane and pointless.

I think some of these viewpoints can be attributed to the bitterness arising from the opposite party insulting their fiction of choice, continuing a vicious cycle.

Some of the most well-known and reknowned was produced as a marriage of both, fostering qualities of genre-wide appeal and literary intellectual-ness.

Some writing programs have certainly gone in the write (heh) direction by taking a step back in commanding what should be written, and instead focusing on helping the students elevate the type of work they wish to create. Other programs need to follow suit!

As a person who is in their second year of college with a plan to get a MFA in creative writing, this article is very eye-opening and is making me rethink any plans I have.

Glad I found this article. A prof told me about it in passing, but I didn’t catch where he found it.

This is something I have been thinking about more and more lately, and while I am still in my early years of earning an English degree, I have definitely already noticed this distinction in the works I study. Thankfully, I have professors who are well aware of the current divide and are actively working to provide more diversity in the classroom. Well done and very informative piece.

A very interesting article. I recently completed a masters in creative writing here in Australia and the students frequently debated over the value of popular fiction/genre fiction vs literary fiction. Interestingly, given we were in a university setting, all 24 people enrolled in the course were working on genre novels.

Here in Australia, there does seem to be a raise in genre studies within Universities; senior lecture Kim Wilkins at QUT for example specialises in genre studies.

The peculiar insistence on the “right way” to write is what turned me away from doing a Creative Writing degree at uni.

They had one of those open days where you can go and listen to the course admins promote the course. So I went and sat in on the one for the “Bachelor of Creative Writing” or whatever it was called.

Well, the course admin said: “I’ll bet you all have stories and novels that you’re working on…” We all nodded, believing it was some kind of in-joke. “My advice,” he continued, “is to chuck it all in the bin. We don’t encourage creativity in this course. We will force you all into one format – so, if that doesn’t appeal to you, leave now.” The saddest thing is that he wasn’t joking.

So, I left. My principles did not align with the principles of the uni course. It seems sad that one has to fit either genre or literary fiction. People seem to believe you can’t do both. Am I not allowed to just write? If it sells, it sells; if it doesn’t, so be it…

I’m studying a Bachelor of Creative and Professional Writing and I haven’t found it a bad thing at all.

None of the lecturers or tutors have disdained genre, or implied that any type of writing is more ‘intellectual’ than another, in fact, many have focused on a variety of forms.

Everything I do at uni is valuable and has helped me as a writer. I’ve become much more widely read, I’ve learned to be critical, I’ve become much more attentive to detail.

Perhaps the best thing, is being in a space where I can share my work with people who share my interest in writing. Listening to their thoughts and experiences has made me understand people in a more nuanced way, and I think that understanding is reflected in the growing complexity of my characters.

University is a wonderful place if you put in the effort to explore and take advantage of the resources.

Literary or mainstream, people write for a reason. And if that “mainstream” writing is able to make readers feel something important, or encourage a wider reading public, it holds as much value as “literature” in its own way.

This subject is very interesting. 😀

This is a really interesting article! I had no idea there was such a difference within fiction.

Interesting article! I’m starting my studies for an English Literature major this year, although I am planning on switching from that to Creative Writing. Hopefully, I won’t suffer through similar issues in my program.

I have been studying creative writing at university level as a mature age students (in Australia), and found it endlessly fascinating and useful. Genre fiction is certainly acceptable here, and there is a huge amount of scholarship on the subject these days.

Thanks for this article. I’m considering getting an MFA, but clearly have more thinking to do, especially in light of this. I have no issue with literary fiction, but as a person who also has her favorite genres, I resent that professors often think of said genres as less than worthy. If those genres are what make people love to read in the first place, I say university MFA programs should teach more about them. And yes, please, can we dispense with the repetitive canon of (mostly) dead authors? Not that I don’t love the classics, but I have yet to see any contemporary stories taken seriously in most university courses.

I feel like genre fiction is more accessible/meant for the masses. It explores themes and conflicts that can be thought-provoking or enlightening (I’m thinking of ‘The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.’)

There is a lot of fluff out there, but it’s not fair to look down on all popular published books.

I definitely see the divide of ‘scholarly literature’ and genre fiction from both professors and undergrads. It’s pretentious when they look down on anyone who enjoys anything besides canonical literature. We should encourage people to read whatever they enjoy.

The likes of Bradbury, Shelley, and Le Guin proved that the depth and analytical appeal of literary fiction can apply to genre fiction premises and concepts. Having an interest in and extensive knowledge of the human condition can benefit characterization and thematic potency, something that can be turned into a vibrant metaphor via genre fiction templates like SFF and horror.

Doesn’t anybody else feel like all this only applies to the English speaking world (in the Global North)?