Pursuing Equity When Writing Diverse Characters

“Write what you know” is a popular adage, and for most writers, it works. Our bookshelves and e-readers are filled with autobiographical novels that touch minds and hearts because they are so close to the authors’ own experiences. When a novel isn’t autobiographical, it often speaks directly to its author’s lived experiences in some way. There is nothing wrong with this. Yet, most writers venture away from writing what they know at some point, because the well of lived experience can run dry. Female writers want to delve into male characters’ psyches. White authors seek to create and represent more characters of color. Temporarily able-bodied authors explore the disability experience. This can and does result in a more diverse and multifaceted literary canon.

However, unless the author has lived a certain experience for him or herself, writing good representation is difficult. Authors who write about characters and situations outside their own racial, religious, geographical or ability groups are often criticized and sometimes vilified. It takes time, effort, and finesse to write well outside one’s own experience, but that doesn’t mean it can’t or shouldn’t be done. In looking at various positive and negative examples, writers can learn more about how to craft diverse representations well.

Racial Experience and Diversity

Skin color, therefore race, is one of the first diverse things people notice about each other. Unfair as that may be, it does facilitate conversations about different experiences, specifically how race has been treated and portrayed over time. Many white authors endeavor to write authentic racially diverse characters and stories, despite the problems that can arise for authors writing characters outside their own races. Specifically, authors writing racially diverse characters–particularly white authors writing black or Hispanic characters–must usually contend with histories of discrimination, subjugation, and abuse that they themselves have little or no frame of reference for. Sometimes they succeed brilliantly; other times they fail or fall somewhere in between. For instance, the desire to write white characters who treat minorities with compassion can often cross into “white man’s burden” territory, or make white characters look like messiah figures. Other times, authors who aren’t racially diverse fall back on using white protagonists when a black, Hispanic, or other racially diverse person would be a better choice.

Despite these pitfalls, some writers succeed brilliantly in writing racially diverse characters. Others’ efforts are not brilliant, but noteworthy and well-regarded. Even examining where authors fail can teach amateur writers a lot about how to treat diverse racial experiences with the respect and care they deserve.

The Help, Kathryn Stockett

Published in February 2009, Kathryn Stockett’s The Help was an instant hit. New hardback copies flew off the shelves, giving way to paperbacks audiences devoured. About three years later, the bestseller was turned into an acclaimed movie starring Viola Davis, Emma Stone, Jessica Chastain, and Octavia Spencer. The Help is set in 1960s Jackson, Mississippi, so racial and race relation themes are almost a given. The way they are tackled, however, is unique to Kathryn Stockett, both her positive choices and writing mistakes.

Kathryn Stockett is a white woman who grew up in the 1960s and had “help” in her family throughout her life. Thus, that aspect of the novel is somewhat autobiographical. In author’s notes and interviews, Stockett speaks and writes about the black maids who raised her and made indelible impacts on her life. Aibileen and Minny, the two major maid characters, are not completely based on real-life women. Yet Stockett’s years of experience around black maids and their culture, as well as their triumphs and tribulations, help her make Aibileen and Minny multifaceted people. Neither woman is a caricature or stereotype, and neither is a victim, although the racism in their city certainly tries to victimize them.

Aibileen and Minny have had diverse experiences with racism and racial culture, and both women handle them differently. Aibileen Clark, the older of the two, lost her son Treelore when his boss dumped him out of a truck in front of a segregated hospital after a work accident, leaving Treelore to die. During her interview with author Eugenia “Skeeter” Phelan, Aibileen notes this is the moment when “I didn’t feel so accepting no more.” In other words, Aibileen had rolled with the punches of her community up to then. She didn’t like being subjugated, but accepted it as part of what was, often leaning on her faith and prayers to sustain her. For Aibileen, losing Treelore was like losing the last and perhaps only concrete reason she had for acceptance. She tells Skeeter Minny had to pull her out of depression after Treelore died, and that even writing her prayers as she usually does became difficult if not impossible. Aibileen was eventually able to reenter society and keep functioning, but it is implied she still nurses deep, buried pain. Looking after her white “babies,” which used to bring her such joy, is now a tainted task because white people were implicit in the death of her own child. Aibileen does not protest segregation and subjugation; she keeps any opinions on the subject mostly to herself and goes along doing what she’s always done. Yet inside her, there exists the potential to break away from what is safe, normal, and damaging to her. There exists the potential to rise against subjugation in her own way and time, which she does late in the novel.

Minny Jackson is almost the polar opposite of Aibileen. She’s younger and less experienced as a maid and a woman, but this only scratches the surface. For Stockett and readers, Minny represents a more vocal African-American character, one whose struggles with her place in society are closer to the surface. Like Aibileen, Minny loves the white children she helps raise, or often raises herself in the absence of attentive parents. She recognizes she must keep any job she has, partially because of her four young children and her abusive husband, who will not tolerate her unemployment. To that end, Minny constantly coaches herself with reminders like, “No sass-mouthin’,” even when her employers behave unreasonably. She tries to focus on the positive in her work and the people who need and appreciate her, such as Hilly Holbrook’s mother Mrs. Walters. Unlike Aibileen though, Minny has never been able to accept the status quo for long. She flouts it without repentance and enjoys it, at least until the consequences catch up to her. For instance, Minny gets fired for using Hilly Holbrook’s indoor toilet during a tornado. While she relishes the momentary satisfaction, it nets her a beating from her husband, so she’s more careful when beginning work for Johnny and Celia Foote. Yet Minny is so inundated with racism and its fallout, especially as it relates to her kids, that she can’t stay silent for long. In a scene that has become famous yet infamous, Minny gets back at Hilly for firing her, baking a chocolate pie laced with her own excrement. Again, momentary satisfaction is the order of the day when Hilly unknowingly eats two slices of the vengeful dessert. Yet Minny soon realizes she just might get herself killed over the incident. Her only insurance is to have Skeeter write about it in her book, which nearly backfires a couple of times.

Aibileen Clark and Minny Jackson are not the only well-written black characters The Help gives us. Stockett also adds characters like Constantine, the maid who raised Skeeter from babyhood to her college years, and Rachel, Constantine’s daughter. The film version puts flesh on some other characters, such as Yule May, who risks stealing a neglected piece of jewelry from the Holbrooks in order to send her sons to college. In these women, Stockett and film producers explore multifaceted personalities and racial issues. For instance, the motherly Constantine is a bit more open and compassionate than Aibileen. Rachel, like Minny, is vocal and bold in the way she handles racism, though not quite as subversive as Minny. Rachel invites readers to confront issues that were common in the 1960s, such as black people “passing” for white to net themselves better opportunities. Yule May asks readers to deal with a moral dilemma – is stealing, or otherwise breaking the law, wrong when it’s your only choice? If the law is morally wrong, or if the law hurts someone you love like Yule May’s twins, are you within your rights to break it? Other questions arise throughout the book, such as whether Minny’s pie revenge was a true act of civil disobedience, whether Aibileen should have confronted Hilly and given up her job, and so on. Such deep questions and memorable characters prove Stockett can write outside her own experience and do it well.

However, The Help has raised plenty of ire with critics and continues doing so. Although Aibileen, Minny, Constantine, and other black characters are essential, Skeeter Phelan is usually seen as the “true” protagonist. White and black critics alike accuse Skeeter, and by extension Stockett, of participating in “white man’s burden.” That is, Skeeter’s main motivation in writing a book of maids’ stories is to further her own career and help people whose plight “disturbs” her. The latter motivation is noble, but it does come across that Skeeter thinks the maids need to be rescued in some way. Learning the maids’ stories also doesn’t open Skeeter to much change. She recognizes the racism inherent in Jackson is wrong, and she does her best to counteract it with African-Americans she knows. Still, she never challenges her parents, Hilly, or any other white person on racism itself. She’s more likely to challenge what racism leads to and how it affects her, such as how Rachel’s actions led to Constantine’s resigning from the Phelan household. Skeeter also continues holding negative views on issues like interracial marriage. While this was true to the time period and not dealt with heavily in The Help, it does communicate that white values are more easily understood than black ones, and that white people are more sympathetic in general.

Dealing with race relations in any context is tricky, especially in fiction and especially in the time period Stockett chose. Stockett clearly succeeded in doing what she set out to do, writing a book that reaches and entertains people of all races. Her mistakes are cautionary tales for writers, while her successes are good examples to follow. When writing about another race in particular, writers should always represent characters as three-dimensional people. Writers should not be afraid to let those characters do morally ambiguous things, because it makes them more human. Characters of any color should be allowed to relate and mix with white characters as much as possible, even during time periods where this would be frowned upon. However, writers should be more careful than Stockett in how these relations are presented. That is, it’s a good idea to move away from the construct of a black person mentoring, raising, or changing the mindset of a racist or rebellious white person when at all possible. Additionally, writers must be extremely careful not to create a “white man’s burden” scenario. White people should not be portrayed as saviors in any context, nor should relations with them be the only reasons black characters get ahead in life.

The Yada Yada Prayer Group Series, Neta Jackson

Neta Jackson’s novel The Yada Yada Prayer Group burst onto the literary scene as a Christian fiction title circa 2004. It quickly became a crossover, garnering heaps of attention and praise from Christian and secular readers and reviewers. What started as one book blossomed into a six-book series, accompanied by a novella, in the course of about six years. Since circa 2010, Jackson has also written two spin-off series where Yada Yada characters appear in cameos, or where their friends and families are central to the plots.

Neta Jackson resides in urban Chicago and has lived there for many years. Thus, she is surrounded with all kinds of diversity, particularly racial diversity. She writes and speaks about soaking this up and learning from it in her church and personal prayer group, as well as outside religious settings. Although The Yada Yada Prayer Group has a white protagonist, Jodi Baxter, as narrator, several “sisters of color” populate the pages and drive the plot. Unlike The Help, which focuses on black and white relations, Yada Yada features black, Latino, and mixed-race characters. It’s also written in a modern setting, meaning historical constructs such as Jim Crow laws don’t get in the way of interracial friendship or drive interracial conflict. The featured prayer group is a group of twelve, and the narration is first-person. Thus, not every white “sister” or sister of color is central to every plot. However, everyone gets enough time in the spotlight for Neta to develop personalities, delve into issues, and encourage readers to embrace diversity in real life.

In writing her series, Jackson started with the one thing any writer writing outside his or her experience should. She did her research, and it shows. Jackson is white, but regularly spends a lot of time with people outside her racial group. She also takes the time to read, watch, and listen to personal narratives and other stories that tackle race-based issues from different sides. Thus, her portrayals of black, Latina, and Asian women are more authentic. Jackson’s characters do not talk in what she refers to as “street jive,” or overuse cultural dialect or expressions. However, it’s not uncommon for black women to call each other “girlfriend.” Ebonics or other language differences are sometimes present. In Jackson’s books, most of the sisters of color go to a salon that caters to black women’s hairstyles, and this is accepted as natural. Latina women sprinkle their dialogue with Spanish or make cultural dishes for dinner, and it is not uncommon for those women’s faith to have noticeable Catholic elements. One of the Yada Yada Prayer Group’s Asian women is described as quiet and gentle, but not because she is a stereotypical Asian. Rather, it’s because this woman, Hoshi, is naturally introverted. She does express opinions and ask questions as much as any other group member, but introversion is accepted as part of her.

Being true to the nuances of several cultures helped Neta Jackson sell thousands of books, and it helped her books to cross from the Christian to secular market as smoothly as they did. Along with the nuances though, Jackson is unafraid to tackle the complications of racial experience and diversity head-on. One great example comes from the second book in the series, The Yada Yada Prayer Group Gets Down. In the first chapter, protagonist Jodi Baxter accepts a free cut and style from Adele Skuggs, the black owner of the salon many of her sisters frequent, in preparation for her anniversary. As is often the case, Adele’s mother Sally, or M’Dear, is there during the appointment. Sally has full-blown Alzheimer’s, such that she can’t remember the basics of who or where she is at any given moment. When Jodi’s husband Denny comes to collect his wife and drive her to their destination, Sally panics. She assumes Denny, a tall, athletic white man, is a member of a lynch mob – specifically, the lynch mob that killed her big brother decades prior. She throws accusations at Denny and goes into a complete meltdown, leaving Jodi shaken and Adele furious.

Jodi and Denny try to write off this incident as a woman with Alzheimer’s having a bad day, but Jodi finds herself in a bad position when Adele calls to quit the prayer group. “I need a break from white people,” she explains. She goes on to open up to Jodi about her childhood. She describes how, even as a black girl in urban Chicago, she and her siblings regularly faced discrimination. Although they tried to pretend racism did not exist, it clearly did. Jodi tries to convince Adele to change her mind about quitting Yada Yada, emphasizing she and Denny, and the other white sisters, are not racists and should not be blamed for what happened to M’Dear’s brother. Yet for Adele, that’s not the point. Adele is the one who has to watch her elderly mother’s pain, try to keep her calm every day, and deal with the fact that racism is still prevalent. “Don’t complain to me about how you feel,” she snaps at Jodi – and readers can’t help but think Adele has more than one good point.

Neta Jackson brings Sally’s traumatic memory to a touching resolution, when Denny kneels in front of the woman’s wheelchair and personally apologizes for the sins of the man Sally thought he was, and receives forgiveness. Yet, racism is not the only part of the racial experience Jodi and her family deal with as whites in a diverse neighborhood. Jodi, Denny, and others are often called upon to make cultural compromises or accept the beautiful, if foreign parts of other cultures. For example, in book three of the series, Jodi’s daughter Amanda exclusively dates Jose Enriques. Jose is the son of Delores, one of Jodi’s prayer sisters, and it’s clear from the outset he loves Amanda dearly. To show this, he asks permission to give Amanda a quincenara for her fifteenth birthday. Both the Baxter and Enriques families are hesitant, but the Baxters more so, especially when Jodi finds out a quincenara can be seen as an engagement party. “They’re fifteen, for crying out loud!” she exclaims at one point. For her part, Delores thinks the idea is sweet, but potentially too serious for her high school sophomore and his girlfriend. Both women struggle to decide what to do, not only out of cultural sensitivities, but the universal desire to protect their kids.

In the end, both families agree to the quincenara, as a way to show support for Jose and Amanda. They also want to open up their families not only to other cultures and experiences, but other ways of looking at and showing abstract concepts like love or affection. The ceremony is beautifully written. While cultural blending is a factor, Neta Jackson focuses much more on the faith Jose and Amanda share, the love of their families, and the changes that transitioning from mid to late teens will bring. With this particular plot arc, Jackson imparts a few lessons to writers who want to write about racial experiences. First, although racism needs and deserves to be discussed, it need not be the only issue diverse characters deal with. If it is, it should have a new angle, such as M’Dear’s Alzheimer’s and the forgiveness she is able to extend in spite of her clouded memory. Second and more importantly though, writers should balance their time between the unique aspects of race and culture, such as the quincenara, with common ground to which all readers can relate.

Ability Experience and Diversity

Disability is perhaps the most fluid and diverse minority we have. It is no respecter of persons; anyone can develop a disability of any kind at any time. In the not too distant past however, disability was heavily stigmatized. People with disabilities were seen primarily as societal burdens, meant to be institutionalized or at the least, never experience life outside their homes. This has changed dramatically in the last century to century and a half, as people with and without disabilities endeavor to present the stories of this group. However, people without disabilities must be intentional and judicious in how they create those stories and, in the case of fiction, the characters that accompany them.

Out of My Mind, Sharon M. Draper

The latest statistics from organizations like disabled-world.com indicate that 12% of Americans have at least one disability. Of those, the most common motor disability is cerebral palsy. United Cerebral Palsy estimates 800,000 Americans live with CP today, and that 1 in 10,000 children will be born with the condition each year. Cerebral palsy is usually linked to brain damage occurring before or during childbirth. Because different parts of the brain can be injured, every case of CP is different. Some are quite mild, while some are severe. Many protagonists with moderate or severe CP appear in fiction. Sharon M. Draper’s character Melody Brooks is one such protagonist.

Draper does not have CP herself, although her daughter is disabled (Draper does not specify the disability). According to Draper, Melody Brooks is not a portrait of her daughter, but “a character who is truly her own being.” Melody is in fifth grade and has a photographic memory. She adores words and turns them over in her head, enjoying the way they sound and how they fit into speech or stories. She loves country music, lemonade, caramel candy, and dogs. Like any other fifth-grade girl, Melody has a sense of fashion and wants to choose her own clothing. But Melody also has a version of cerebral palsy that makes her unable to walk or speak. She cannot feed herself or take herself to the bathroom. She has never been given the means to tell people, even her parents, what she needs or wants. Thus, Melody is deemed uneducable and consigned to her school’s segregated special education classroom. With a high teacher turnover rate, Melody learns nothing in class, and is often the target of bullies. It is only when she gets access to assistive technology that Melody is finally able to speak and tell the world what she knows.

With the help of her new speaking machine, Melody makes clear her desire and ability to be in general education. She immediately impresses her teachers and earns a spot on the school quiz team. However, even in general ed, Melody’s problems do not go away. Bullying remains a problem from two girls in particular. Worse, the school’s quiz team sponsor seems to think Melody only got her spot because of the college-age aide who helps her type and record answers. At one point, Melody scores highest of anyone on the team in a practice session. The teacher responds with, “If Melody Brooks can get this score, the questions aren’t hard enough,” in front of everyone.

Melody faces ups and downs in her home life, too. Her little sister Penny has grown into an active toddler, and though Melody is sometimes envious of Penny’s abilities, she endeavors to be a great big sister. Penny responds well, growing close to Melody throughout the novel. However, Melody can’t help but notice the stress a toddler and a disabled oldest child place on her parents. She thinks back to when she was little and sat in on doctors’ appointments, wherein it was recommended that she be institutionalized. Melody wonders if, despite her intelligence and ability to function mentally and emotionally in the outside world, this will be her fate.

Sharon M. Draper does a wonderful job of presenting the positives and negatives of the disability experience. Her research into cerebral palsy is thorough and deft, and she is unafraid to show Melody struggling with basic tasks most people take for granted. Yet it is Melody’s personality that comes to the forefront most often. Even when she cannot speak or express herself, Melody uses first-person narration to let us hear her voice. She analyzes her experiences in special education and introduces us to her classmates and teachers, presenting their strengths as well as weaknesses. For example, Melody notes that a classmate named Willy screams a lot to express himself, and it can sometimes be loud and obnoxious. On the other hand, Willy loves baseball and is gifted at remembering related statistics. Similarly, Maria has Down Syndrome and does not always respond to her environment in an age-appropriate way, but she shows great interpersonal intelligence. For Melody and readers, students with disabilities are not anomalies; they are a natural part of the school’s diversity. For Melody and readers, disability is a tough reality, but it does not eclipse gifts, talents, and the value of the individual human experience.

Draper does make some mistakes in Out of My Mind, some of which are redeemed while others are not. Perhaps the biggest mistake is in the climax. Melody acquits herself beautifully in quiz team competitions, leading to acceptance from her teammates and sponsor. In fact, a teammate named Rose seems to offer Melody’s first true, reciprocal friendship. But when the team is invited to Washington, D.C. to compete at state level, Melody is left behind. She misses her flight because, as Melody’s mom finds out later, the team met early to go out for breakfast and didn’t call. They decided, through a silent vote, that it would be too much work to help Melody into the restaurant and feed her. The sponsoring teacher gave implicit permission for the team to board the flight without Melody. Melody and her mother are irate, but no one faces repercussions. In fact, all Melody gets from her team is a sappy apology in which they finally admit they were wrong, but that they should not have left their “inspiration” behind. The sponsoring teacher offers to let Melody keep the team trophy; Melody refuses on the grounds that they’ve already implied she didn’t and couldn’t earn it.

Many reviewers malign Out of My Mind based on this incident. They claim, and rightly so, that it sends a negative message – namely, people with disabilities will never be equal to their temporarily able-bodied counterparts. Even if they have the capacity to earn or win something, they will not get it unless they are first labeled “inspirational.” Other reviewers point to the incident as yet another example in a long list of degradation Melody and real-life people with CP experience. They ask why characters with disabilities are never allowed to triumph or be happy outside their ability to benefit non-disabled persons. This is a prime example of what speaker and disability rights activist Stella Young once called “inspiration porn,” or the portrayal of disabled persons as superhuman when they do everyday things. If Draper meant to circumvent inspiration porn, she unfortunately fails in this instance.

Draper tries to redeem the mistake with one more climactic event. Melody insists on going to school after the quiz team humiliation, explaining she will only give her detractors what they want if she doesn’t show. Unfortunately, it’s a gloomy day marked with torrential rain, and Mom is already exhausted from taking care of little Penny. She and Melody get into an argument, at the end of which Mom blows up – “I’m taking you to school and I hope they keep you!” On the trip over though, a harried Mom neglects to strap Penny into her car seat. Melody notices and tries to alert Mom, but doesn’t have her speaking device handy, so can only scream and grunt. Mom takes this as a sign of Melody throwing a tantrum and scolds her, until she finally realizes what her older daughter is trying to say. Mom reacts just in time to get between Penny and a car that loses control and hits the Brooks’ vehicle.

Penny sustains injuries, but Melody is credited with saving her life. Note she does this without her speaking device, therefore without expressing herself the “correct” or “accepted” way. In allowing this, Draper somewhat redeems the quiz team incident, showing people with disabilities can be heroic and their ways of communicating are as valid and important as anyone else’s. Whether Melody’s story is completely fair to people with disabilities is debatable, however. That is, it is only when Melody saves another, temporarily able-bodied person, that she is seen with much value through the eyes of the school and community. Even her loving parents admit they have always underestimated their daughter, despite believing in her intelligence. Draper’s unconscious message seems to be, people with disabilities must always go the extra mile to prove their value. Innate talent, intelligence, and compassion are not enough – it is only by physically doing something that people with disabilities can hope to be included in society. This remains a true experience for many people with disabilities, one that advocates, authors, educators, and others work every day to change. However, Draper’s novel does not do as much as it could to underline the need for change, or express that change is possible.

Out of My Mind, then, is both a positive example and a cautionary tale for writers. Many writers with disabilities already pen their own experiences for the public, but just as many temporarily able-bodied authors write about disabilities, too. If you are a temporarily able-bodied author writing about disability, take a page from Sharon Draper’s book. Do thorough research, and present as realistic a portrait of your chosen disability as possible – through the eyes of a three-dimensional person. For every discriminatory incident your character goes through or every “simple” thing they struggle with, give them a legitimately triumphant moment, a strength, or a talent. Allow characters with disabilities to build and maintain authentic friendships, and to have natural reactions, such as Melody’s anger at her mom and quiz team. At the same time, beware the uber-inspirational climax. Let any final triumphant moments or apologies for ableist attitudes happen organically. Show characters with disabilities doing everyday things without getting undue praise or credit that’s out of proportion. Allow these characters to recognize and make up for their mistakes, to be the snarky voice in the group, and to be the ones who provide help as much as they need help.

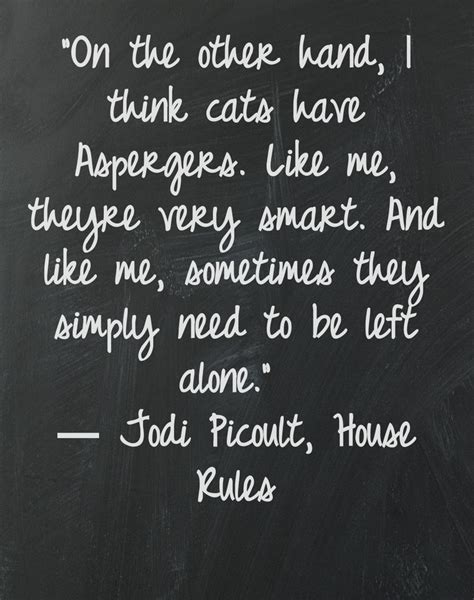

House Rules, Jodi Picoult

Jodi Picoult, a bestselling adult author, is best known for engaging stories that turn on complicated moral fulcrums. Many of her characters also deal with illnesses or disabilities. Jacob Hunt, protagonist of House Rules, is no exception. Jacob is a forensics genius with an affinity for chemistry and related sciences. He often shows up at crime scenes as an unseen spectator, but finds things the police miss. Were he considered able-bodied, Jacob would be a community wonder. However, he has Asperger’s Syndrome, a form of high-functioning autism. Jacob struggles intensely with social cues and falls back on monologuing about his interests when social interactions fail. He cannot make eye contact. He is extremely dependent upon routine, becoming highly upset if his schedule is disrupted. For Jacob’s brother Theo and their mom Emma, this stuff is part of everyday life. Yet that changes when Jacob’s social skills tutor Jess is found dead, and Jacob is accused of her murder.

Picoult is a genius when it comes to crafting complex storylines, but she does not have Asperger’s Syndrome herself. Discerning readers will notice this immediately when studying Jacob Hunt’s character. Many facets of Jacob are true to the Asperger’s experience, such as his limited and intense interests in forensics and criminology. Jacob also has many quirks real-life people with Asperger’s might recognize. He finds the tastes, textures, and colors of certain foods offensive, and only eats certain color foods on specific days to help facilitate routine. He likes to hang his clothes according to the color spectrum ROYGBIV, and his timing is always exact. If Jacob’s favorite show comes on at 4:30 PM, he will be home to watch it at 4:30, not 4:25 or 4:32. These quirks aren’t problematic, but many reviewers think Picoult overloads Jacob with them. In addition to the quirks named here, Jacob has a bevy of others; it seems Picoult gave him a version of every quirk someone with Asperger’s might ever experience. In addition, she shows Jacob having violent meltdowns several times throughout the book, especially in public. Sometimes these meltdowns further the plot; they are used in the case against Jacob when he becomes a murder suspect. Other times, they perpetuate a stereotype of autistic people, especially males, as potentially violent and unable to recognize their own emotions.

Picoult’s stereotypical picture of autism and Asperger’s continues throughout House Rules, not only with Jacob but with other characters. She spends a lot of time dwelling on the fact that Jacob looks guilty because he doesn’t look police in the eye during interrogation, or because he answers questions with a flat affect. Picoult uses neurotypical characters like Jacob’s mother Emma and brother Theo to drive home the point that Jacob has no empathy. In chapters from her point of view, Emma constantly worries over Jacob, analyzes him, or frets over his future. In many cases, she comes to his defense after an outburst or unsuccessful interrogation, as any mother would for a son like Jacob. The problem is, Emma comes across as naive or hysterical in her presentation. As for Theo, he regularly admits to himself and readers that he’d like it better if Jacob weren’t around. He gives us detailed accounts of incidents where, for example, he couldn’t go to the DMV to get his driver’s license because it would disrupt Jacob’s routine of going to the library or local price club for groceries and free samples. Whether Picoult meant to do this or not, she makes Jacob look like a borderline sociopath who deserves what he gets. Failing that, she makes Jacob look pitiable, such as when an overzealous state attorney purposely plays up his quirks in court, mocking and triggering them.

While this is a clunky and sometimes horrid way to present a disabled character, Jodi Picoult does a few redeeming things in House Rules. While their points of view are problematic, the presence of Theo and Emma’s perspectives lend authenticity and diversity to the story. People with disabilities interact with the non-disabled every day, and some of those interactions are intensely negative. Even the family members of disabled people undergo stress and tension, or have emotionally charged interactions, though they love their family members and want to do what’s best for them. Secondly, the fact that Jacob is a murder suspect gives House Rules a distinct edge over similar books. That is, most readers never expect a protagonist with a disability to get in trouble or interact with constructs like the justice system. Stereotypically, protagonists with disabilities are supposed to be innocent and sweet. They might be smart or witty, or have cynical edges, but they are never supposed to be a threat to others. The fact that Jacob is considered such, and must traverse that, makes him an engaging if overblown protagonist. Readers keep reading, and rooting for him, because they are never sure whether he actually committed murder. Jacob becomes the epicenter of a page-turning mystery and thorny moral dilemma, something most protagonists with disabilities don’t experience.

While this is a clunky and sometimes horrid way to present a disabled character, Jodi Picoult does a few redeeming things in House Rules. While their points of view are problematic, the presence of Theo and Emma’s perspectives lend authenticity and diversity to the story. People with disabilities interact with the non-disabled every day, and some of those interactions are intensely negative. Even the family members of disabled people undergo stress and tension, or have emotionally charged interactions, though they love their family members and want to do what’s best for them. Secondly, the fact that Jacob is a murder suspect gives House Rules a distinct edge over similar books. That is, most readers never expect a protagonist with a disability to get in trouble or interact with constructs like the justice system. Stereotypically, protagonists with disabilities are supposed to be innocent and sweet. They might be smart or witty, or have cynical edges, but they are never supposed to be a threat to others. The fact that Jacob is considered such, and must traverse that, makes him an engaging if overblown protagonist. Readers keep reading, and rooting for him, because they are never sure whether he actually committed murder. Jacob becomes the epicenter of a page-turning mystery and thorny moral dilemma, something most protagonists with disabilities don’t experience.

House Rules is much more a cautionary tale than Out of My Mind, presenting writers with many things they should not do. Notably when writing disability, do your research but do not hit readers over the head with it. Do not cram your protagonist full of quirks, idiosyncracies, and struggles. Sometimes, as in Jacob Hunt’s case, a disability and everything that goes with it will make your protagonist look guilty of something, or like a bad person in general, even if it’s not true. That in itself is fine if it moves the story along, but overloading the protagonist makes it seem as if you’re going out of the way to present a negative portrait. Additionally, give your protagonist consistent allies, whether disabled or non-disabled. Let that friend or family member speak to their stress if needed, but let the person stick by the protagonist no matter what. Allow and expect allies to focus on the disabled character’s strengths and assets, not weaknesses, quirks, or failures.

Religious Experience and Diversity

Religion is arguably more important than ever when it comes to diverse experiences. According to a 2016 Huffington Post article by Antonia Blumberg, the face of American religion has changed but still remains influential. In the 1960s, 98% of Americans polled said they believed in God. That number is now down to 86-89%, according to Gallup and Pew researchers, but is still a huge percentage. Currently, 2/3 of Americans identify as some religion, with the other third claiming no affiliation but often noting spirituality is important to them. The term “spiritual, not religious” is often heard these days, especially among younger generations crafting their own religious identities.

With over half of Americans polled – 56% – saying religion is very important in their lives, one might expect to find religiously diverse books everywhere. Unfortunately, this is not the case, especially among children’s and young adult novels. This is not for lack of interest, though; it can be traced back to some problems inherent in writing about religion. Many authors seem most comfortable writing from their own religious experiences, if they tackle the subject at all. In fact, as Aaron Hartzler of the Children’s Book Council blog notes, it’s difficult to find religion as a central theme in any genre other than historical fiction. Most religious fiction, especially Christian fiction, is clearly marked as such and can be moralistic, which pigeonholes it among readers.

This said, religious diversity is not a completely foreign concept for readers and it shouldn’t be for writers. There are contemporary writers who have tackled religious diversity through making faith an organic part of a character’s experience. As with our other two types of diversity, some of their techniques work better than others, but they are worth analyzing.

The Poisonwood Bible, Barbara Kingsolver

The Poisonwood Bible, with a Christian allusion directly in the title, is one of Kingsolver’s best-known books and one of her most popular. Set in the 1960s Belgian Congo, it counts as a historical novel. Yet Kingsolver successfully writes it so that religion and other issues feel as contemporary and universal as they actually are. Many of today’s missionary boards require trainees to read and discuss The Poisonwood Bible before going out into the field. The novel centers on the four Price sisters – Rachel, Leah, Adah, and Ruth May – and their mother, Orleanna. The wife and offspring of an autocratic fundamentalist pastor, they are uprooted from their home in Bethlehem, GA to serve as missionaries in a Congolese village.

The misunderstandings and culture shock readers might expect ensue. However, Kingsolver takes a unique tack in that she lets us see actions and reactions from both sides of the religious equation. For instance, the Price family is disillusioned and upset when they find out their African neighbors don’t accept baptism as a religious rite of passage. For the Congolese, the water is dangerous, so getting dunked in it – and risking being torn apart by crocodiles – to prove you are “saved” seems barbaric. Yet this is not a simple tug of war where being saved spiritually is juxtaposed with keeping safe physically. The Christians are not presented as complete villains who can’t learn from their neighbors. Pastor Nathan Price, who clings to his intolerance, is presented this way. Yet the Price girls, especially Leah, show understanding when they see why baptism is taboo for the Congolese. As time goes on and the daughters see their father floundering in his conversion efforts, they side with the Congolese more often on religious and interpersonal issues.

Kingsolver also succeeds in writing a religiously diverse book because she shows that conversion to one religion is not the only option if characters want a good life. Nathan Price certainly believes so, as do Orleanna and at least two of his daughters. At the beginning of the book, Leah idolizes her father and sees him as righteous, so she goes along with what he says, does, or thinks. At only five, Ruth May is too young to know any better, while Adah is a somewhat closeted skeptic and Rachel is downright vain, cynical, and the antithesis of a “good Christian girl.” Yet the longer the Prices are in the Congo, the more they see exactly how their neighbors worship and why their way makes sense to them, as well as why the Christian way might not. Leah in particular increases her knowledge of the oppression the Congolese experience under French colonialism and the “invasion” of American, French, and Canadian missionaries. She learns her Congolese neighbors, while not fundamentalist Christian, are rich in faith. Many of them worship in time-honored, traditional ways of their country, and gain peace or security from doing so. Sometimes this is thrown together with a mishmash of Catholic beliefs, which they got from Brother Fowles, the missionary the Prices replaced. It is heavily implied that Catholicism, while not wholly embraced, was accepted over the Prices Southern Baptist Christianity because Brother Fowles was much more willing to get to know his neighbors as people and respect their beliefs, such as the belief in the presence of nature spirits and ghosts, or the power of witch doctors. For their part, the Price women don’t know what to do with this. Only Leah comes to any sort of religious epiphany, and that’s being generous. She never shakes her fundamentalist upbringing. She never says or implies that the Congolese beliefs she encounters are superior. But on the other hand, she is far less inclined to say her own religion is superior. Though it takes a while, Leah, of all the Price women, is the most open to meshing her faith experience, therefore her identity, with that of a people and country she doesn’t fully understand.

Much later in The Poisonwood Bible, Leah marries a Congolese teacher named Anatole. While religion of any kind doesn’t play a big role in their marriage, Leah’s standing as a “missionary kid,” later a missionary teen and missionary woman, certainly does. By this point she has aligned herself with the Congolese, wholly sympathetic to their political struggles and right to live as they choose in an un-colonized country. Still, she is white, American, and an outsider, as she is subtly reminded every day. Leah still finds herself confused and even repulsed at how her neighbors choose to live everyday life, without the modern conveniences to which she is accustomed. She still feels the inner struggle between herself and her family, who grudgingly accept her marriage but are not as warm and supportive as she might have hoped. Perhaps now more than ever – more than when she was a young teen enmeshed in the Southern Baptist culture of baptism, soul-saving, and fiery sermons – Leah Price feels the label “white Christian.” Perhaps now more than ever, even outside of her religious experiences, she must fight to make a place for herself in a world where she has never quite fit in.

Kingsolver did spend some time in the Belgian Congo (formerly Zaire, now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo), but was too young to get involved in the questions of politics and religion as her protagonists do. When she wrote The Poisonwood Bible, it had been well over twenty years since she visited Africa’s interior. She writes about living a life of sheltered normalcy in her author’s note for one of the book’s editions. With that in mind, how was she able to craft a multifaceted story, especially one that takes a critical look at religious experiences? The secret lies in how committed Kingsolver stayed to the book, and how she used both memories and research to inform her writing. If you are going to craft a religiously diverse story in any context, commitment to the story must be paramount, if not commitment to the religion itself. Like Kingsolver, many writers use their own religious experiences as jump-off points for this type of story, but it’s not enough. Writing a religiously diverse story actually means stepping back from the religious aspects at times. It means being willing to look outside your own lens and through the lenses of others, so you can treat their points of view with care and respect. It also means being willing to accept the flaws of your own religion or worldview lens, as Leah Price slowly learns to do during her time in the Congo.

My Heart is on the Ground, Ann Rinaldi

Ann Rinaldi is a prolific and bestselling writer of historical young adult fiction. She is also an author this writer enjoyed immensely in her preteen and teen years. However, her one foray into religious diversity garnered heated reactions and abysmal reviews, which makes it worth a look for writers who wish to avoid the same mistakes. My Heart is on the Ground, a book in the well-loved Dear America series, is about Little Rose, a Sioux student at Carlisle Indian School. Little Rose has her name changed to the more acceptable, “white” name Nannie when she arrives at Carlisle, and is forcibly assimilated into white culture. In the process, she loses touch with much of her culture, but especially her Sioux beliefs.

Rinaldi does not let Little Rose talk much about religion in her diary, but what is there stands out. Little Rose’s beloved grandmother, for instance, is a highly spiritual woman who regularly helps the young people of her tribe prepare for vision quests or otherwise get in touch with the spirit world. One of those people is Little Rose’s best friend, Lucy Pretty Eagle, who has been taught to control her epilepsy and bring on spiritual trances to communicate with those in other realms. Little Rose speaks at length about wanting to be pure enough to find her spirit helper, a guide who will appear as an animal and help her become a grounded, spiritually mature young woman. She tries to perform rituals from home to encourage her spirit helper’s appearance, although the teachers and administrators of Carlisle quash this. Little Rose also expresses confusion regarding Christianity and her white teachers’ “Jesus god.” She admits some Christians, like Quaker women who visit with Christmas gifts, are kind, but she never expresses interest in their beliefs because she already has her own, even if they are suppressed. She writes about attending Sunday school and chapel, but admits she gets nothing out of it, nor does anyone else. “We just sit there and let the Preacher Man talk to himself,” she says of fellow students in one diary entry.

These piecemeal observations give readers a glimpse of Native American spirituality, but not enough to paint a true portrait of Sioux religion. If anything, Rinaldi treats Native American religion as a homogenous entity. She mentions a Hopi rain stick and Hopi healing methods exactly once; otherwise, all the students in Little Rose’s school, regardless of tribe, appear to subscribe to the same religion. Rinaldi, who is herself white and Catholic, also writes with a tone that hints Christianity is superior and more civilized than Native American beliefs. Little Rose never says this, nor do any other students. No one in My Heart is on the Ground converts. However, Little Rose constantly embraces the influences of white Christianity and culture, and finds them superior to what she calls her “blanket Indian” lifestyle. In one scene, she cuts her growing hair and slashes her skin in mourning after the loss of a dear friend. This is considered a sacred emotional and spiritual ritual among her people, but Little Rose immediately agrees not to finish the ritual after a teacher catches and reprimands her. In another key incident, Little Rose sees her brother outside her dormitory window, performing a war dance. Instead of being comfortable with this, she is ashamed of him and scolds him about making trouble for her and the rest of the school.

These and other instances of oppression – religious in particular but also otherwise – earn Rinaldi plenty of criticism. One Amazon reviewer calls her a “New Jersey culture vulture” who did nothing with this Dear America installment except disrespect Native American heritage. Other reviewers, whose grandparents were in residential schools, accuse Rinaldi of “whitewashing” the truth, especially where religious education and conversion are concerned. One reviewer relates a story her grandmother told her about a schoolmate who got pregnant while at a Catholic residential school for Native Americans. “The nuns dressed the baby up in a pink outfit [and]…threw it in the oven. You could smell the flesh cooking,” she writes. Bear in mind these actions were from a group of nuns, from a denomination that is now intensely pro-life. Similar stories populate history as well as critical reviews of My Heart is on the Ground. Yet to hear Ann Rinaldi tell these stories, the life of a residential school student was almost idyllic. The fictional Little Rose writes about eating chocolate cake, winning prizes for her sewing at a fair, going on field trips, and learning wonderful new things. When her spirit helper is killed, she mourns for a while, but moves on arguably too soon. She also questions her best friend’s commitment to Native American spirituality and whether it is the best route for her in the white world. When the opportunity to leave Carlisle Indian School arises, Little Rose is actually sad to go.

This is just a sampling of Ann Rinaldi’s poor treatment of Native American spirituality and culture. Educated reviewers and detractors have uncovered that she stole names from the gravestones of children who died in residential schools like Carlisle, using them as character names. She has also been accused of misappropriating and misquoting historical sources. My Heart is on the Ground is not her only book to receive this treatment, either. In any of her books where whites and Native Americans interact, one can expect to see whites look down upon and criticize Native American culture, especially religion. Broken Days, wherein protagonist Walking Breeze is regularly shamed for her beliefs, is only one example. Though both books were published in the late ’90s they, and My Heart is on the Ground in particular, feel woefully outdated and ethnocentric.

A book with so many detractors does have a lot to teach writers though, especially about religious diversity and the acceptance of diverse beliefs. The most obvious lesson revolves around compassion and acceptance toward those whose beliefs are different, which Rinaldi’s characters don’t show. Beyond that, several smaller but vital lessons exist. For instance, religion is clearly a huge part of Little Rose’s life, but Ann Rinaldi glosses over it. For any writer, this is a poor choice. If you want a protagonist to have faith, particularly one different from what your audience has experienced, show it. Give the faith dimension and let it be real, without making the character too lax or devout for the story’s parameters. Show characters following and learning from faith traditions. Additionally, let your religious characters stay true to their faith, even if secrecy and persecution are the order of the day. Do not fall back on conversions; even when writing for an inspirational market, be careful with these. Conversions, if they exist, must be genuine and rooted in a character’s well thought out decision to make the change of his or her free will. Even then, the original faith need not be abandoned or treated as a lesser option. Finally, do not be afraid to share the truth about religious struggles or holy war, even if it’s ugly. As we know from Ann Rinaldi, whitewashing truth only leads to anger, disillusionment, and pain.

“Write what you know” is a good adage, but writers can grow professionally and personally if they craft characters and stories outside their own experiences. Writers should embrace diverse experiences and characters as much as possible, but with care. However, this goes far beyond doing research and refusing to stereotype characters. Those things definitely help; for instance, any good story needs three-dimensional characters who feel as real to us as any person we know outside the pages. But when writing outside one’s own experience, a writer also needs commitment to story. More than perhaps any other type of writing, writing outside experience requires the whole brain and the whole heart. Writers must be willing to explore all avenues and as many facets of character as are relevant to the story. They cannot let their plots be too thin or overdone. They cannot let their characters down, because to do so is to let the readers down.

In writing outside experience, authors must also be as honest as possible. Sometimes, that honesty will mean confronting ugly truths, either past ones that we’ve worked to change or present ones that still need attention. Never be afraid to confront what you find. Writing is not traditionally considered a dirty job, but writing outside experience requires getting messy. In the midst of the mess, writers will probably make mistakes. The key is to correct them as best you can when they are found, and stay true to the universal story you want to tell. Remember that black or white, disabled or non-disabled, Christian, Jewish, Hindu, or atheist, everyone has a story to tell. Everyone has something to say about themes like relationships, faith, love, death, vengeance, and many other universals. Writing these things well is quite a leap, but for those with the right preparation, it can become a successful experience.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

An enjoyable essay to read, well developed, well researched.

Wouldn’t normally have the wherewithal to venture deep into such a splendid article. However, Bryce Howard is Hollywood royalty and that was enough to draw me into the writing (helps to be as attractive and talented as she is too). Wonder what your next project will be, Drew Barrymore?

Who knows? Ever After in particular is one of my favorite movies, and Barrymore’s portrayal of Cinderella is quite possibly the best I’ve ever seen.

Thank you so much for writing this post, as it’s been something I’ve thinking about a lot lately.

Writing contemporary YA means I try to write as realistically as possible, and my most recent story is about a girl who grew up going to Catholic school in a small town. After I finished the first draft is when I started hearing more and more about We Need Diverse Books–which is awesome–but it really got me worrying that my book wouldn’t get picked up because it’s not diverse enough.

Write with diverse characters but don’t write about existence as a diverse character.

The vast majority of people who care about representation are discerning readers. But buying and reading one book over another is a bigger commitment than watching a film or starting a TV show, so word of mouth is really, really powerful.

Diversity is sometimes controversial. All writing is controversial if you’re writing about something important and you’re running the risk of getting it wrong – but if you aren’t daring to write about something important, and you aren’t prepared to work on getting it right, then why are you writing at all?

Well-said.

Seems to me that if you’re a white writer trying to write POC characters, there are three outcomes: you do it well, you do it poorly, you do it mediocrely.

You do it poorly, you toss it in the wastebasket, like every other piece of crap writing you’ve done.

You do it well, you sell it, no problems.

You do a mediocre job, you rework it until you make it better and get it done.

The only possible problem you might have is if you write something you think is good, but other people thing is crap. Which sounds to me like a common occurrence for EVERY writer, whether or not the character is a POC.

Write. Make it good. And you have resources to be able to make it good.

Those are also the same outcomes for writing white characters.

Although I haven’t written anything that’s been published, I can sympathise with fearing I’d be seen as crossing the wrong boundaries by writing main characters of minority backgrounds. It’s a tricky question of wanting to put the least-told stories at the forefront, but already hearing the arguments anyone could make against them. “Why not let someone of this background tell their own stories?” “Is this cultural appropriation?” “Is this glossing over a culturally specific struggle, or emotional exploitation for trying to use it?” All of which would be valid questions.

There is such a need for more diverse fiction with trans, ace, non-binary, and other minority protagonists.

As a trans woman, I have had a hard time finding books with trans protagonists, aside from transition stories, romance, and erotica. I wanted books with trans characters that didn’t center around their identity. Crime fiction and sci-fi and fantasy with cisgender characters generally doesn’t center around their cisgenderness.

So since I couldn’t find the kind of books I wanted to read, I’ve started writing them.

Great. Write the book YOU want to read!

Thank you for opening up an important discussion, reading the responses has been a wonderful continuation of a great article.

Important subject, and fascinating perspective. Thanks Stephanie.

The backlash against so-called cultural appropriation is a thing that really puzzles me. The hero of my recent historical fiction novel is a black Jewish man. So am I allowed to write about such a character because I’m Jewish, or is it cultural appropriation, because I’m a white woman? I say, always write people, not cardboard outlines, and you should be fine.

All authors should be able to write about different kinds of characters as long as they do the research.

This article has really given me life and really put a lot of my own concerns and anxieties around my books to rest, at least temporarily (and I think a certain amount of anxiety is healthy). I’m an aspiring writer who is currently trying to get published and one of the biggest goals of my writing is that I want to write diverse books and books which actually look at issues of prejudice, injustice, etc.

Hopefully, when and if my books finally get written, I’ll be one of the names on that list of white writers who have done diversity well and who has helped to make the literary world more diverse because it really is so important to me.

Great piece. Diversity isn’t about having every book shoehorn a tick-list of diverse characters into the story (the irish one, the black one, the asian one, the woman, and the gay one…), it’s about making sure there’s a wide variety of books with a wide variety of characters for a wide audience to read. You do not have to tick every diversity point in one go, and in fact, it’s probably advisable not to try!

White writer here, and I think the work to properly write diversely has really helped me become a better person. I have so many friends stressed and terrified the last few years, especially since Trump took office. I’ve learned about injustices past and present, and more ways women and POCs are struggling today than I thought possible. And while I can’t write from certain viewpoints as well as those actual people can, I can’t help but feel I have a duty to aid in representation however I can, small as my efforts might be in the grand scheme of things. It’s a big world out there, and there’s a lot of work to be done.

The public needs to see themselves reflected.

As a mixed person (half Dominican, half white) I consider this pretty important to me. I grew up surrounded by white people because my Dad came to US with my Mom in a pretty white southern area. And I was blessed to live a pretty much un-prejudiced life. To all my white friends and family, I was Hispanic, and that was that. I think along with writing diverse casts, a lot of that is missing, just being who you are because that’s who you are.

There doesn’t have to be a reason you’re main character is black or Asian or Hispanic (as in writing about racial struggle.) We are who we are because we are. As I’ve grown older I see what people of my race, and other races go through, and I’m not saying it’s not important to write books with characters who deal with racial struggle, I’m just saying that’s not all there is. I also think it’s important to write diverse casts because in all honesty, as a child, I wanted to see people like me on T.V and in books, but I never did. (Still waiting on my Hispanic princess, Disney! Esmeralda doesn’t count.)

And I also think we shouldn’t feel guilty about writing white main characters. As I said earlier, we are who we are because we are. And sometimes that’s white. But there’s a world of possibility out there, so when a character comes to you as Hispanic or black, or Asian, write that character.

I know this comment has been pretty rambly, but I feel strongly about this topic.

I think diversity is incredibly important. I grew up somewhere very white, middle class and pretty homophobic. And yet, as I happened to grow up reading authors like Stephen Fry, who have gay and bi characters, I grew up with much more open, positive attitudes. Writers can change attitudes and change lives.

Thanks to all my readers for these great comments! Batista, Limon, Cristi, patt, and so many others…wonderful points. I think as more writers write the books they want to read, and write characters as they come to them, the canon will become more diverse and more representative of true experiences across the spectrum. In the meantime, as has been said, we need not feel guilty for writing the characters and experiences that come to us…because someone needs to hear and read them.

I think stories with a diverse cast can strengthen it. I don’t know if there is such a thing as creating too many diverse characters, but it makes for interesting stories, if done properly.

I try to write as diverse as my storyworld allows. I get a little sick of the pressure though.

I love how writers complain about “diversity” while they put their (usually male, white, cis, hetero) characters doing stuff and retorting the narrative to the extreme to make them fit the story

We do need more diverse writers, to portray all the different cultures appropriately.

Most importantly, writers careers won’t be over if they make a mistake writing diverse characters.

An important character in my fantasy trilogy is bisexual, but I didn’t make him bi for the sake of diversity or to fit into a subgenre. It just fell in perfectly with the plot and character, and I went for it.

There’s always a danger that the discussion of topics like this can end up being worthy, dull, and pious. None of that here, just intelligent and perceptive points.

A thorough and comprehensive look at the topic through a range of different books. Interesting take here.

Even though I am consciously aware that my fictional worlds are, well, fictional, I still think it really adds depth to the story if it gives a realistic take and mirrors the real world. I know a lot of people who aren’t the perfect weight, or are really short, or are a different ethnicity or have a low income. My sister who I’m super close to is lesbian and gender fluid. I think it would be awesome if everyone who doesn’t fit into a little box has someone they can relate to in books.

I very much appreciate your knowledge and understanding of these various characters and their creators. I think it can be a very challenging line to cross when people of one race are writing a character of another. It’s very important that people are capable of this in respectful and true ways. It’s so important to be conscious throughout the entire writing process of issues that may arise.

For me writing about diverse characters only extends so far, you cannot presume to understand the struggles or simply even understand the small mundane differences in others lives, without attempting to truly know those individuals. I have read novels where a character who is a minority was incredibility written, and I have read novels where I could not get past the first couple of chapters because of my distain for the two dimensional character meant to suffice the minority checkbox. It should be remembered that characters that are a minority do not only have that to define them, it does not do the character any justice to include them, only to never make them a true character at all.

While this was true to the time period and not dealt with heavily in The Help, it does communicate that white values are more easily understood than black ones, and that white people are more sympathetic in general.

Stephane,

Well-written and thoughtful analysis. Perhaps you could clarify the above quote. Kudos that you tackled this tricky subject in a way that gives respect to diverse views. I think that there should be more collaborative writing, like the Artifice!

I enjoyed your article and agree with many points, such as authors who wish to write from another cultural point of view must research that culture first, and even interact with its people.

One thing that needs correction: a sweet fifteen party is spelled “quinceañera”, and it is not intended for engagement. It is a time to celebrate a young girl’s becoming a woman (transition from late childhood to young adult).

This is a thorough and very well-written article! Thank you for writing such a good piece, and for all of this fabulous insight. It’s a tough balancing act for writers to have good representation and diversity in their stories, especially for children’s lit. I grew up hard of hearing and struggled to find characters that were easy to relate to. Now as I write my own stories I try to keep that little girl in mind and provide a wide cast of characters that rep as best I can the individuals that need their voices heard. This article does a great job of highlighting this importance, and the controversy surrounding all of these diversities. It was a pleasure to read!

Just learn by not doing what they did with the infamous Jar Jar Binx.

This article categorizes representation into “compromising” acts by the author and “redeeming” acts by the author. It reads a bit like a pros and cons list at times.

The argument of whether or not someone is allowed to touch on subjects that don’t necessarily involve them has become stronger than ever today. People are either worried about offending the other party or how their work will be vilified in one way or another for trying to increase awareness. Once a certain diverse character is on display for entertainment that automatically leaves room for criticism. If you follow the guidelines of how to be more diverse you might be considered too stereotypical and if you try to stray from the ordinary you’re considered abandoning traditions and culture of the character. Finding balance within anything in life is key. There are so many subcategories to every single person that it will be difficult to achieve representation. However, with true and full background research of the character the writer is going for, it will be one step closer to having many believe they’re having their story read instead.

This was such a great article. Really well written, developed, and the research is fantastic. I’m so glad I found this article. I think the one thing that more writers can do is have the type of people they’re writing about involved in the writing. Take time to speak to the person of color you’re writing about, the member of the LGBT+ community, an individual with a disability. These people are so important and deserve to be included in the process, not just thrown in to try and add to the plot or make a writer look “woke.”

I very much enjoyed this article. Thank you for writing it!

I was nervous about this topic but so glad to write it as well.

This is a powerful set of insights into writing a diverse group of characters. I found that, as I read it, several characters from my latest novel kept coming to mind, and in the course of this introspection, I went to my “Character file” (where I tell, in narrative form, my characters’ lives and quirks and capabilities). For one character in particular, a complex and convoluted black man from Alabama who, among other things, is a literal tech genius, an All American college football player (who passed on going pro for a couple of good reasons). He’s gay but closeted, devoutly Christian despite the apparent conflict between his faith and his sexual orientation, the son of a single mother who never met his father (and, on his 18th birthday, learned the secret that his father was white). In short, he’s a fully-developed and complex character – but in reading this article, I was moved to add to that mini-bio i write about all of my characters, to better round him out as a black, gay man of faith.

This sounds like a beautiful character and I hope he gets a great story! 🙂

As a writer myself, I relate to this peice.

I should be writing about my own culture, my own experiences, and I do, yet it’s always fun when you try to write about somebody else. However it’s difficult and you can hurt another person feelings if you do not do their culture or race justice.

Yet if we were to stick to what we know, we would not have the desire to a step out of our comfort zone and learn.

I do think it’s important to include diverse characters in stories to have the audience open and aware to different perspectives.

The Help seems to avoid certain issues of siphoning from experiences not your own, because many of the experiences relate to the author’s own and are immediately accessible.

This was a great read, very thought-provoking, thank you.