A New Age of Collaborative Storytelling? Critical Role and D&D Livestream

For more than forty years Tabletop Roleplaying Games (or TTTRPGs) have been a staple of ‘ludic cultures’ 1 – a term used to explore the growing world of gaming and gamers. The growth of digital streaming and online gameplay has contributed to a massive expansion in the diversity of folks playing these games, but even-more-so the amount of people watching others play as a form of online entertainment. Numbers of online livestreams and viewers can now compete with popular shows on mainstream platforms such as Netflix and Amazon Prime. In particular the prominent popularity of Critical Role, the highest grossing livestream on Twitch, has given researchers and fans alike a new way to engage with this vibrant community. A closer look into the growing global culture surrounding TTRPGs can help hardcore fans, casual gamers and total noobs appreciate how these games, and their digital streaming, are bringing people together in a world that so often seeks to drive us apart.

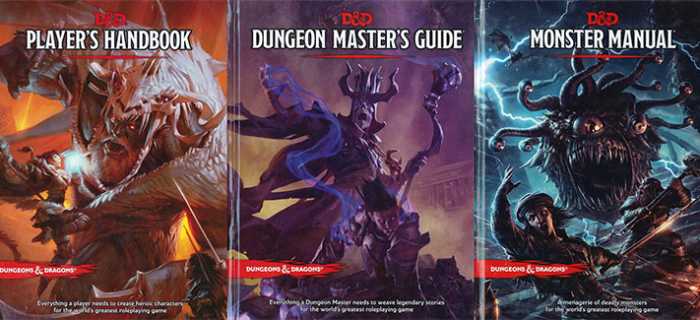

Dungeons and Dragons is perhaps the best known of all TTRPGs but there are a host of games, and of livestreams, where you can watch people playing different kinds of roleplay games. “Why focus on D&D then?” you might ask? Because it is the first, and arguably most popular, of all roleplaying games and despite the lockdowns that have driven so many people apart roleplaying has survived and even thrived over the last three years. Roll20.net – an hosting platform for online play – shows that 52% of all subscribers play D&D, making it by far the most popular game on the service. A range of sources estimate between 13 and 50 million people play the game world-wide. A large contributing factor has been the accessibility of the 5th edition ruleset, 2 but players continue to play all five editions of the game currently available on the market. This is a global phenomenon and an established and vibrant contributor to the world of gaming.

For the uninitiated, D&D is a ‘medieval fantasy’ roleplaying game, but it also provides players with a loosely structured rules-led collaborative storytelling experience unique to roleplaying games. This is the biggest difference between traditional computer roleplaying games and table-top roleplaying games. In the computer game players are always limited in the actions they can take by the sophistication of the programming code. IN a table-top roleplaying game there are no limits, the rules provide a structure similar to that imposed by programming code, but the collaboration of players allows the rules to be ‘bent’, or even entirely ignored, in the interest of telling a cool story. This distinguished table-top roleplay games from computer games, which despite attempts to recreate the Dungeons and Dragons experience are limited by the capacity of the programming and code in a way that collaborative storytelling is not.

This is a contested claim – a theme which will be returned to throughout this discussion – because D&D is not a completely open system. To play one must have a character sheet, must use simple ability statistics that determine the capacity of players to do things in the game and the rolling of dice to help resolve in-game interactions. This ‘ludic’ quality adds a degree of chance to every social or combat action – where failure is as much fun in success in creating memorable moments of narrative. The rules and structures of play are a guide to the experience, but the use of imagination within that is near limitless.

As mentioned above, Dungeons and Dragons is not a universally applauded, loved or lauded experience. A lot of negative attention in the past has emphasised the mystical nature of the content as evocative of ‘satanic cults’ – particularly in the 1980’s during the ‘satanic panic’ in the United States. Further criticism has been levied at TTRPG culture as a space of exclusionary ‘gatekeeping’ by hyper-masculine and outcast ‘nerds’ and ‘geeks’, a common criticism of ‘internet’ and ‘gaming’ culture more broadly.

These conditions have been documented – however, whilst one should not erase or downplay the harmful effects of toxic behaviour within gaming communities to focus only on that aspect of TTRPGs provides a narrow and out-dated view of the culture, the games and the people playing. Negative behaviour is, and will always be, a factor in some gaming circles. Experiences brought to life by the tragic happenings surrounding ‘Gamergate’ as well as a growing diversity of both gamers and game creators has encouraged high-profile attempts to address issues such as toxic masculinity and gatekeeping. To repeat old criticism as if a universal truth does not advance a critical awareness of the gaming community or the changes within it. Rather, it limits our insight to an embittered and inaccurate representation of the turn towards collaborative storytelling, as represented in much D&D livestreaming. The more vociferous critics claim that pejorative values, behaviours and perspectives are ubiquitous to TTRPGs; being built into the rules as preconfigured ideological bias that is inherent in Western culture.

A closer look into the livestreaming community demonstrates a very different picture. A slow but steady transition away from the outdated mythology of ‘blokes in basements’ is gathering pace, encouraging an inclusive and diverse community of acceptance and self-care amongst participants and a celebration of alternative identity that is increasingly savvy in negotiating the all-to-often toxic terrain of identity politics. A closer look at the contemporary trends in D&D – as more broadly of the TTRPG as culture – shows that the rules themselves can be reshaped by players, adapted and ‘homebrewed’ to creatively empower players as they create their own stories. A greater awareness of diverse sexualities and gender identities is acknowledged in the 5th edition players handbook. The livestream as an extension of these changes taps into a growing community of collaborative storytelling where designers work with fans, players and audiences to breathe new life in the experience of TTRPGs. The content produced by these gamers increasingly reflects values of identity diversity, tolerance, acceptance, and love. New forms of real and virtual community are emerging from the world of collaborative storytelling as the accessibility and production value of smaller content producers increases. Into this vibrant world, the live-streamed TTRPG has emerged as a small, but significant, player at the forefront of a new age of digital community.

A community of practice

A community of practice can be described as a human collective. But it is also more than that. There is a binding between members, often informal, connecting them through the shared passion and mutual expertise in some kind of collaborative enterprise. The term is more commonly used in organisational and educational research but here it helps us understand the emergent properties of TTRPGs as well. The collaborative enterprise of the TTRPG group functions as a space of empathy and connectivity far beyond the ‘playing of games’.

To be considered a community of practice a phenomenon requires that there are regular interactions and a general desire for common improvement in the mutual capability of those so engaged. A regular gaming session provides this. What makes the livestreaming of gaming sessions so interesting is that by bringing small, intimate gaming sessions to a mass audience the potential for community creation is significantly expanded. A shared domain of common interest becomes significant to the participants when it enhances the common knowledge about the shared activity and shapes conduct of participants – both within game itself as well as informing value-led conduct of participants in the world beyond the game. This can be equally true of managing a project for a client as it can for running a role-play campaign for a group of players. The group comes together and all are changed by the interactions, but in a way that empowers new possibilities for positive conduct in world writ large.

The emerging networks of content creators, observers and participants surrounding the TTRPG livestream provides a ripe body of data to explore this, but has remained on the fringe of studies into games and gaming – compared to Massively Multi-player Online games (MMOs) and other digital innovations. By engaging with the D&D livestream as a form of global entertainment these cultural products reflect the interactions of content producers and community participants. And with estimates placing players at between 13 and 50 million world-wide, it is cultural phenomenon of significance. If we want to look for a positive story of change in our world, this is a good place to focus.

For example, livestream platforms (e.g. Twitch.tv) and other online re-broadcast services (e.g. YouTube), online forums and message-boards (such as Reddit) provide a rich vein of data – from fan conference panels, interviews, livestreams of gaming and online discussions of game content and more. These can be reassembled to trace the development of shared repertoires and common experiences that make this community of practice unique. These conditions ‘mutually inform’ the commonly understood tools and techniques that bring people together. For TTRPGs this is perhaps most relevant to the experience of gameplay, but it is also relevant to the conduct of individuals as members in a community with shared values beyond the game. For livestreaming, specifically, this interplay of online performance and offline practice is an emerging phenomenon with the potential to change the way people interact in ways that go far beyond collaborative make-believe to the promotion of empathy amongst both groups and for individuals.

Why livestreaming?

Formally understood as ‘User-Generated live video streaming systems’ this technology allows anybody who is viewing digital content on their personal computer to broadcast a video-stream of that content in real-time onto the Internet. Widely popular amongst eSports and independent content producers platforms such a YouTube and Twitch.tv provide a digital space from whence content creators can broadcast live and recorded gameplay. A feature of content is often gameplay itself or advice about games supported by discussions of gaming culture, with a strong orientation towards the acquisition of subscribers – who may pay a small fee for direct live-access to content or whose subscriptions provide an audience for marketers. Content creators are thus able to sell advertising space and acquire subscription fees as sustainable income from content production to global niche audiences of cultural consumers – many of whom are also engaged in the same activity as a recreational, semi-professional or professional practice.

Sometime community members are involved in their own content creation, others often in affiliated industries – from custom dice to custom miniatures to cosplay, fan-fiction and more. In 2017 alone over 7,500 unique broadcasters provided access to D&D-based content online for more than 475 million minutes of media, acknowledged as a major contributor to the current popularity of the game and to the record profits of Wizards of the Coast and its parent company Hasbro across the last 5 years and more. These numbers continue to increase in 2024, making the TTRPG as culture much more important than most gaming researchers are willing admit.

Members in such communities work across platforms and practices to drive broader strategies; create new businesses; address and quickly solve problems within the community – as well as the games they participate in; transfer best practices surrounding TTRPGs to other groups; enhance and develop ways of making a living out of ones passion, and encourage others to do so as well as, at times, collaborating to enhance new talent and bring attention to other emerging initiatives – from charitable funding drives to emerging products or productions. All of these features match the requirements to establish D&D as an emerging community of practice.

A note on TTRPGS, internet culture and the livestream

It would be disingenuous to suggest that the livestream is the only reason that roleplaying games have reappeared in the public imagination. ON the Artifice, and other platforms, there has been discussion of the diverse factors influencing the rise and rise of roleplay, not limited to: a resurgence in 1980s nostalgia in popular culture; the maturation of a generation of nerds and gamers many of whom grew up playing TTRPGs; and highly successful entertainment shows such as Stranger Things – which prominently features Dungeons and Dragons tropes.

Others draw attention to the mainstream cultural acceptance of fantasy and science fiction through the growth in popularity of Lord of Rings films or Marvel superhero movies. Two more niche oriented but no less significant to our story are the web-comic Penny Arcade – which spawned a host of Dungeons & Dragons live podcasts, amongst their other content – and the internet entertainment channel Geek and Sundry – which has continued to popularise both role-play and other ‘nerdy’ games through their online channel. These forms of digital culture link online and offline phenomena that draw together the culture of TTRPGs predating the internet as we know it today but continue to have a lasting impact on how individuals and groups make meaning in the offline and online worlds. Whilst Penny Arcade pre-dates Geek & Sundry, the latter was the launch platform for the Critical Role livestream – so it to this our attention is now turned in drawing out the significance of Critical Role, in particular.

Geek & sundry, Critical Role and the livestream

Founded in 2012 – by Felicia Day, Kim Evey and Sheri Bryant – and funded in part by the 100 million dollar ‘YouTube Original Channel’ initiative, the content of Geek and Sundry was to focus on positive representations of nerd culture. Shows would explore comedy, gaming, comics, music and literature promised a new alternative for content creation to the tired tropes of US-focused network television.

The channel emphasised positive representations of “geek” or “nerd” culture “as a chosen identity rather than a label” whereby “engagement with geek culture is depicted as an effective method of understanding oneself and the world”. Shows offering satirical but generally positive reflections on nerd culture included The Guild, exploring the lives of a team of gamers in a Massively Multiplayer Online game (MMO), in sharp contrast to prominent network TV shows like ‘Big Bang Theory’ in which the scripted identities offer complex representations of, largely negative or socially dysfunctional stereotypes. Other shows like Tabletop offered gameplay walkthroughs and demonstration of innovative tabletop games, featuring nerd celebrities and hosted by actor Will Wheaton. Through these tropes we see the roots of a culture that bridges online and offline interactions, a strong identification of social category – i.e. nerd / geek etc. – as a strong features of the identities portrayed. However, it is through the arrival of livestreamed role-play games that we see the emergence of meaning generation through a performative culture of practice begin to emerge more clearly.

In 2014 Geek and Sundry launched Critical Role. The show was to be aired weekly featuring livestream of a long running D&D game using the 5th edition ruleset, published in 2014. Experienced Dungeon Master, Matt Mercer, runs a game for ‘a bunch of us nerdy voice-over actors’ building on the campaign that he ran for a group of close friends. Whilst Critical Role is a key focus for our discussion moving forwards it must be acknowledged that a long-standing and pre-existing community of practice surrounds games and gaming culture. Gaming conventions like Penny Arcade (mentioned above), PAX and E3; alongside TTRPG and broader gaming conventions like GenCon; as well as the cross-over of various fandoms from popular culture that fuel both competitive and recreational cosplay at fan conventions; the growth of events such as the Magic: the Gathering ‘Mythic championship’ events and the emergence of comparable competitive e-sports events – such as QuakeCon – have all thrived in recent years. Many of these are both broadcast on the internet and observed as ‘live’ spectator events. It is into this context that that livestreamed TTRPGs have emerged as a gateway into a new age of a collaborative storytelling informing an emergent, creative community of practice.

Fan engagement, sponsorship, Charity and community building

Fan engagement is an important bridge between the paying of games and the creation of community. It has also been a central feature of the product since its inception on Geek & Sundry, the hashtag #letsplaytogether featuring in the banner art for the very first episode in 2015. Since then a community of dedicated followers has developed. A dedicated fan-run statistics service linked to Critical Role shows that the collective have streamed over 830 hours (and growing weekly) of role-play game content one Twitch.tv – first on the Geek & Sundry channel and then on their own dedicated Twitch channel. This includes the core campaigns, with over 758 hours of content playing D&D, run in the ‘home-brew’ game setting ‘Exandria’ – created by Matt Mercer. This number rises when including the ‘one-shot’ single games, with guest stars, featured settings or single-play role-play games other than Dungeons and Dragons. 3 Since launching their own dedicated Twitch.tv channel the collective have accumulated over 370,000 subscribed followers, 8.74 million discreet views of channel content with average viewership of 12,798, peaking at around 65,000 views during scheduled D&D gameplay content. 4

No small contributor to the success of the show is the calibre and breadth of talent demonstrated by the well-loved voice actors, who are responsible for voicing many cult classic video-game franchises from Street Fighter, Final Fantasy, Uncharted and the Last of Us, as well as animated classics including Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and anime series (e.g. Full Metal Alchemist). Early on in the livestream fan art was submitted from the viewer community, which was rapidly incorporated into the show and online platforms through a view-feed of curated pieces shown in the livestream itself – during the mid-session break, leading to the release of a fan-art book based on the chronicles of the characters in the first campaign.

Community sponsorship and support for the show from the game designers themselves at Wizards of the Coast soon followed, with sponsorship deals running shifting from local businesses (such as internet cloud service Backblaze) to focus on TTRPG producers specifically – such as table-top scenery company Dwarven Forge, the kickstarted roleplay journal company Rook and Raven, and others. This level of generative engagement has scored well with fans of the show who have also heavily backed the ongoing charitable outreach of the company.

From the outset Critical Role has sponsored local charity 826LA, who work out of local branch offices to improve literacy amongst under-privileged children across the USA. They have also expanded incorporated fund raising drives into the stream itself in a number of creative ways. A fundraiser for charity Extra Life in 2015 raised over 20,000 USD for the Children’s Miracle Network, on broadcast. Interactivity was ensured in earlier episodes by including donation amounts and messages as pop-ups in the livestream feed and the cast and crew thanking donors directly at the end of livestreams, reading a list of donors on air. As the show viewership expanded throughout 2015 the cast produced a “Critter’s Guide to Critmas“, ‘critters’ being the tag applied to the growing fan-base of the show. This was tied to the growing number of gifts sent directly to the cast from their fans; the guide asked ‘critters’ to donate directly to suggested charities instead of sending gifts for the cast, each cast member sponsoring a different charity.

Another fundraising drive for 826 LA in early 2018 saw donations tally over 50,000 USD, the total matched by a community member acting as sponsor for the event; however the group also incorporated the reward mechanisms of platforms like Kickstarter, where tiered donations could unlock discount codes for Wizards of the Coast online platform D&D Beyond and show sponsor Wyrmwood Gaming, as well as unlocking new content to be later produced and broadcast by the Critical Role platform – in the form of a ‘Fireside Chat’ – the second of its kind – with Matt Mercer, and a second one-shot of the game ‘Honey Heist’ to be run by Marisha Ray as the Dungeon Master for a day. Perhaps the most significant of recent charitable community events was the high-profile team up with satirical news broadcaster Stephen Colbert (a long-time fan and childhood player of D&D) for Red Nose Day 2019. Donations allowed viewers to vote on certain elements of the adventure, which they could then see played out on the livestream, raising 117,176.20 USD in total.

The incorporation of crowd-funding strategies for charitable funding which also tiers into content generation and expanded audience base shows a level of charitable innovation and business savvy that ties into the second of the two most valuable products being shown through critical role – that of the cast themselves, their generous natures and the relationship between the cast as friends with a desire to do good in the world more generally – a fact acknowledged by Marisha Ray in a discussion panel at Google in 2018.

Deeply ingrained in the public imaginary of internet culture is an understanding of the hazy boundaries between reality and fiction. From fictive unreality of dystopia on ‘The Matrix’ to the backlash against ‘fake news’ in a post-Trump era wider media products and culture create a unique appreciation of the fluid relationship between concepts of self and other, the real and the unreal, the imagined and the factual. In this sense for many consumers of modern media one can propose that reality may be tied to diverse and relative contexts rather than fixed, determinate and objective. Such lofty notions aside, a community of practice surrounding TTRPGs and the livestreaming of D&D provides a performative window through which we can view and begin to deconstruct a more hopeful vision of human culture, than that of the lonely robot rationally calculating their next advantage in the entrepreneurial marketplace of real life. The community of practice that encourages charitability, empathy, an acceptance of diversity and human connection through shared storytelling links back to a primal need in human life. Collaborative storytelling maybe engaging the artifice of shared fantasy but it also pump-primes the capabilities of humans to feel for one another, to work together and to feel just a little less alone in this world of individualised perpetual growth.

Livestreams allow those unfamiliar with the TTRPG – but commonly a fan of correlated products and material of the fantastic and fictive – to engage with a new form of storytelling previous only available to players at the table who had been inducted into a play-group through carefully controlled channels of access. As the gatekeepers become less common and the barriers to participation are lowered the potential for roleplaying games to encourage a greater empathy amongst players in growing – as are the number of participants eager for a fix of human connection. The common themes of inspiration, friendship amongst players, creative expression and exploration of the self in a safe environment are very engaging for people who have been isolated and diminished by the hyper-reflexive and hyper-individualised forms of alienation embedded in convergent media mono-culture. Or in more simple terms, sick of being stuck in lock-downs over the last three years.

Exploration of the self can be rendered playful and empathy inspired through the common interest of collaborative story-telling, rendered dramatic and real to participants by the genuine qualities of co-engagement in collaborative fiction. Players are becoming proud ambassadors of the positive impact of TTRPGs, emphasising engagement and participation in the common practice of gameplay whilst providing an example of one way this can be enacted, which in turn reinforces the cycles of positive feedback for all members of the community. The accessible nature of the human content – for example in Between the Sheets interview series – humanises the fantastical with a focus on the lives of players and participants. This adds to the growing connection between the performed participants, their characters performed in story and their life stories in a far more real sense than fictitious narratives dramatised through mainstream entertainment products.

In blurring the boundaries of reality and fiction in playful ways the TTRPG livestream often encourages a common engagement in the values of a shared community of practice. Content creators at Critical Role often emphasise the empowering possibilities of TTRPGs as a means to widen adoption of the game amongst new players and provide evidence for the positive impact prosocial impact of TTRPGs for players. This alone should encourage researchers to take research into TTRPGs more seriously as the boundaries of self and other, reality and fiction, community and individual become ever more complex and the community of practice surrounding what we do and why become, even more, important to our readings of contemporary culture.

Works Cited

- A good overview of ludic culture as a theory, though focused on video games a little more than I would like in this context, can be found here. Dovey, J., How do you play? Identity, technology and ludic culture. Digital Creativity, 2006. 17(3): p. 135-139.. ↩

- Sales (of the Players Handbook, but also other content on and offline) continue to increase in 2017 by over 44% from the previous year. Brodeur, N. Behind the scenes of the making of Dungeons & Dragons. 2018 May 4, 2018 at 6:00 am [cited 2019 01/06/2019]; Available from: https://www.seattletimes.com/life/lifestyle/behind-the-scenes-of-the-making-of-dungeons-dragons/.. ↩

- Such as ‘Honey Heist’ designed by independent game designer Grant Howitt (https://gshowitt.itch.io/honey-heist) ↩

- This data is provided by TwitchTracker – https://twitchtracker.com/criticalrole/statistics (access: 10/09/2019) ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Great article. CR has truly opened the doors for aspiring DMs like me to embrace storytelling with confidence. Watching Matt Mercer seamlessly guide his players through complex scenarios while incorporating their input inspires me every time.

Love them. This kind of accessibility is a far cry from the intimidating manuals and insular groups that dominated TTRPG culture when I first tried to get into it.

Well, as a Twitch streamer myself, I like how they maintain audience engagement while staying true to the authenticity of their gameplay. The inclusion of fan art and live chat interactions during the stream creates a symbiotic relationship between creators and their audience.

Yea, it’s a masterclass in balancing entertainment with sincerity, something many streamers, including myself, strive to achieve.

Roleplaying and cosplay. The perfect blend.

Watching the cast dress up as their characters makes the story feel so much more alive!

Feels like a celebration of creativity!

The show wouldn’t be possible without the advancements in livestreaming technology, and it’s a great example of how tech can bring niche communities together.

Watching Critical Role feels like watching an improvisational theater production. The cast’s ability to stay in character, even through unexpected twists, is remarkable. It’s reminiscent of long-form improv troupes, but with the added layers of dice rolls and world-building.

My son got into D&D because of Critical Role, and it’s been such a positive influence on him. He’s developed better communication skills, learned to think critically, and even started writing his own stories. It’s refreshing to see a show that promotes creativity and teamwork rather than mindless entertainment.

They have done more to popularize D&D than any single product or campaign module since the game’s inception.

The inclusive atmosphere is one of its strongest aspects. It’s heartening to see LGBTQ+ characters and themes explored naturally within the narrative.

Representation like this matters, especially in a medium that has traditionally been dominated by cisgender, heterosexual perspectives.

The show’s embrace of diversity feels authentic and has helped create a welcoming space for fans from all walks of life.

While I appreciate what Critical Role has done for the TTRPG community, I do worry that it sets unrealistic expectations for new players. Not everyone has the skills of professional voice actors or the resources to create detailed maps and props.

Exactly. It’s important to remember that D&D is just as rewarding in simpler, less polished forms.

They can sometimes unintentionally overshadow those grassroots experiences.

It’s the collaborative effort that really matters!

The humor is one of my favorite parts.

Totallllyyy! Whether it’s Sam’s ridiculous antics or the witty banter between the players!

This show has done so much to bring people together, and it’s a beautiful reminder of what fandoms can achieve when they’re rooted in kindness.

There’s something profoundly philosophical about Critical Role’s narrative.

It reminds me of existentialist thought, where characters are constantly defining themselves through their actions.

From a cultural perspective, Critical Role is a phenomenon that deserves to be studied more seriously. The way it integrates live performance, participatory storytelling, and digital interaction creates an entirely new form of entertainment. What fascinates me most is the audience’s role as both observers and contributors, whether through fan art, real-time comments, or charity donations. It’s like a blend of ancient oral storytelling traditions and modern social media. Shows like this could signal a shift in how we consume and create narratives in the 21st century.

I’ve been rolling dice since the days of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, I can’t overstate how much they have done for this hobby. Back then, D&D was often misunderstood or stigmatized, but this show has brought the game into the mainstream and made it accessible to people from all walks of life. I’m particularly impressed by how they handle the roleplaying aspect—it’s less about min-maxing stats and more about creating compelling, emotional stories. It’s a reminder of why I fell in love with D&D in the first place.

Mercer’s ability to adapt to player choices while keeping the story engaging is something I aspire to bring to my own projects. Im a gamedesigner.

I’ve been following Geek & Sundry since the days of The Guild, and it’s amazing to see how the platform has evolved over the years.

Critical Role feels like the culmination of everything Geek & Sundry set out to do. Highlighting positive, creative aspects of nerd culture while fostering a sense of community.

I don’t even play D&D, but I’ve been hooked on Critical Role ever since a friend recommended it.

I’m considering joining a local game group. They have made the hobby so much more accessible.

I’ve started using elements of D&D in my classroom, inspired by Critical Role. Story-driven gameplay engages my students in ways traditional teaching methods often fail to. It’s amazing to see kids who struggle with social skills suddenly come alive when they’re playing a character. Critical Role provides an incredible template for how storytelling can teach cooperation, empathy, and problem-solving—skills that are so crucial for young people today.

I’m always impressed by how they incorporate giving back into their streams in creative ways.

It’s rare to see such a large community so mobilized for altruism.

I didn’t think I’d enjoy watching a group of people playing a game, but it’s so much more than that.

It has great characters who are relatable, complex, and inspiring.

Peak DnD. It’s almost therapeutic in a way, both for the players and the audience.

It’s not just about the game; it’s about the shared experiences, emotional depth, and connections it creates. Watching the players navigate challenges and grow their characters is incredibly cathartic, almost like therapy through storytelling—for both them and us as viewers.

This has given me the courage to try DMing for the first time.

The comparison between Critical Role and shows like Big Bang Theory is spot on. One respects nerd culture as a meaningful identity, while the other reduces it to a punchline.

I’ve always found it frustrating how mainstream media mocks people like me for loving what we love. Critical Role flips the script and shows that being a geek isn’t about stereotypes—it’s about passion, creativity, and community.

It’s incredible how TTRPGs like D&D can act as a tool for mental health, and Critical Role is a perfect example.

I’ve even heard of therapists using role-playing as a form of treatment for anxiety and PTSD.

The way the players interact with the world reminds me of games like Skyrim or The Witcher, but with even more freedom and creativity.

I love epic fantasy series like The Wheel of Time, it’s thrilling to see similar depth and complexity in a collaborative format.

As someone who used to play tabletop RPGs, I’ll admit I can’t quite get into the idea of playing online. There’s just something about rolling dice in person that the internet can’t replace. That said, we all have to adapt, right? In my case, I’ll stick to not playing, haha. Still, this was a great read and really complements the shift in how storytelling is evolving!