The Tempest: Shakespeare’s Final Stage Magic

Shakespeare’s final play, The Tempest, was written in a world in where the influence of the English language was expanding. Beginning in 1476 when William Caxton established the first significant English press in Westminster and continuing on through the next century with the mass publication of various versions of the Bible in English, the English language grew into textual legitimization (Crystal, 56). The discovery of the Americas and the spread of colonization carried along this newly-printed language. As a result of this geographic expansion, English was constantly changing and evolving while still growing in power and legitimacy. Alien places and people naturally required the English language to mature. William Shakespeare’s plays brought this evolving language into physical form, and no other play but The Tempest best embodies the meeting of alien places and people. In the microcosm of his plays, Shakespeare used language to transform and shift an audience’s perception of the world as the play unfolded on the stage. In The Tempest, Shakespeare utilizes his power as a playwright to construct a world in which the ephemeral, the physical, and the theatrical seem to mesh together seamlessly into a tale of profound vengeance and reconciliation.

The Tale of The Tempest

Years ago, Prospero was the Duke of Milan, and he spent his days ensconced in his study in pursuit of mystical knowledge. Prospero’s brother, Antonio, accused him of shirking his duties as Duke and usurped him. Antonio and his conspirators left Prospero and his young daughter, Miranda, to die stranded on a raft at sea. Luckily, their raft made its way to a (almost) deserted island where Prospero plotted his revenge.

The play begins twelve years later with Antonio and other men from the court of Milan on a ship at sea, in the grip of a great tempest. It seems this storm was summoned by Prospero’s magic, and he brings the men ashore to his island to exact revenge. With the help of his servants Caliban, a half-demon monster, and Ariel, a shape-shifting spirit that is at times more terrifying than Caliban, Prospero toys with his enemies as they wander throughout the island, often through the marvelous spectacle of his magic. But by the end of the play, Prospero summons his enemies to him in the spirit of forgiveness. His daughter, Miranda, marries the son of one of Prospero’s former enemies. Finally, Prospero casts away his magic staff and returns to Milan.

Within The Tempest, language has a great power to control and mystify, and in a similar way, Prospero, the magus and protagonist, uses his magic to control the other characters around him. The words that the characters speak are used to affect change in one another, quickly and severely, changing motivations and appearances frequently. The magic power of words keeps this play in a constant state of change. This change makes it possible for alien worlds to collide, alliances to form and break quickly, and perceptions to shift. But in time, Prospero’s perception of the world is changed, as well, and he renounces his magic altogether.

Historical Context

The period in which The Tempest was written was full of discovery, as well. Shakespeare composed his writing in one of the most formative eras of the modern English language: the English Renaissance. Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, great scientific and exploratory discoveries occurred (e.g. the works of Copernicus and the colonization of the Americas) which literally changed the way people viewed the world. As the world expanded rapidly around them, English-speakers found themselves in dire need for a new vocabulary. Providing a new vocabulary was the task of writers who looked to other languages for answers: “There were no words in the language to talk accurately about the new concepts, techniques, and inventions which were coming from Europe, and so writers began to borrow them” (Crystal, 60). Shakespeare is famously attributed to many words that are a part of the modern English lexicon, but he was definitely not the first writer of the era to create his own words. A good example of one of these writers is Thomas Elyot who, when faced with translating a Latin or Greek text to English, often created completely new English equivalents for the words that had no simple translation. His purpose was to give contemporary readers of English access to Classical texts. (Crystal, 60) Shakespeare, on the other hand, wrote to enhance the meaning behind his characters’ words and actions. Many words that we use today were first printed in Shakespeare’s texts because he found them to be the best fit in the plays’ form and content.

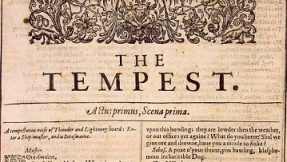

Shakespeare’s final play, The Tempest¸ was first published into print in 1623 in the first Folio (or F1) of Shakespeare’s collected works. This followed his death by seven years. The play was certainly performed before Shakespeare’s death (the earliest recorded account being in 1611), but Shakespeare’s works were not often published into print until many years past their initial production.

Form and Content

As Shakespeare’s last play, The Tempest is often heralded as unique from the body of his later, “mature” plays. John Russell Brown notes several of these differences in his Introduction to the Applause Shakespeare Library edition of the play:

Shakespeare was breaking new ground, not repeating popular successes. For most of his plays, he borrowed a plot from earlier narrative or drama, but here the plot seems to have been entirely his own invention. It uses traditional elements, but in new guises and to new effects. (Russell Brown, x)

One need only to look at the new and strange characters that Shakespeare has placed in his last play. Shakespeare has worked with ghosts of dead fathers and invisible fairies, but he has never created an air spirit that can change shape at will (Ariel). The same can be said for Caliban. Like the weird sisters of Hamlet, he is a character of inhuman origins, but he is unique in his half-human, half-monster dynamic. Because of the many unique traits of the text, The Tempest¸ as the final installment of Shakespeare’s plays, is often viewed as the starkest contrast from the textual and theatrical norms typical of Shakespeare’s other works.

Readers are drawn to specific imagery that constantly shifts and stretches to connect the broad range of symbolism in The Tempest. The material of the play is linked strongly to words like “strangeness” “music,” and “sleep,” and Shakespeare’s repeated choice in these themes endows the entire play with an ever-changing nature. As Reuben A. Brower states in his essay, a result of so much language dealing with “the confusion between sleep and dream and waking” is that “The island is a world of fluid, merging state of being and forms of life” (112). The magic that inhabits the world of the play only serves as a vehicle for the metaphorical language that constantly shifts the audience’s perspective on the events and characters onstage. At first we fear Ariel (as the tempest), then pity him (as a slave of Prospero), love him (as the force that guides the young lovers together), and fear him again (as the harpy that accosts the men of Milan). There are similar character changes for Prospero and Caliban, as well. What Brower states is most exciting about this play, specifically, is that Shakespeare unifies this theme of fluidity in setting, staging, and character: “I am not forgetting that it is a metaphorical design in drama, that we are interested in how Shakespeare as linked stages in a presentation of changing human relationships” (96). Drama, as a genre, uses language as the skeleton of a production; all casting, design, acting, and directing choices are traditionally based in the script. In most cases, it is all things but the words of the play that lend the most obvious spectacle and “magic” to a production. With The Tempest¸ Shakespeare purposefully works in grand metaphor and challenges traditional plot structure to endow the words of the play with a heavier burden of ambiguity. This ambiguity is what allows such dramatic character changes to occur. The play begins with Prospero’s preparations for vengeance, and he exercises control over almost all of the events onstage. Yet the play ends in Prospero’s reconciliation. Shakespeare marries this anger and forgiveness – two contrasting emotions – with the genre of drama which marries the verbal and the active, the magical with the physical.

Reconciliation – Shakespeare and Prospero

Reconciliation is one of the more prominent experiences touched on in this play. Many critics choose this word specifically when referring to the last several plays that Shakespeare wrote, and there are seemingly none that argue against its thematic relevance in The Tempest: “No one can react to Shakespeare’s later plays in a block without recognizing that the subject which constantly engaged his mind towards the close of life was Reconciliation” (Quiller-Couch, 15). Whether or not Shakespeare’s original audiences connected the dots, scholars find that the character of Prospero’s reconciliation with Antonio is symbolic of Shakespeare’s reconciliation with many different and openly debated issues surrounding the playwright as he neared the end of his life. Perhaps Shakespeare understood himself as Prospero, or the island, and he dramatized an old man’s wish to join with the main body of humanity, forgiving all past transgressions. As the play wanes, so does Prospero’s lust for revenge, and his violent attitude with Antonio shifts into an amiable one.

Prospero, as the protagonist, is subject to many scholars’ intense focuses. The character of Prospero is afforded a great amount of supernatural power onstage, and as Prospero exercises control over the elements and other characters, parallels are visible to a playwright’s control over the world of the play. As John Russell Brown states in his introduction to The Applause Shakespeare Library: The Tempest, “Prospero . . . is like a dramatist in charge of a play: noise, music, change of scene, action, marvels, and human encounters all occur as he wills them” (ix). This parallel is the foundation of the conception that Shakespeare modeled the character of Prospero after himself, an artist nearing the end of his life. The Tempest, after all, is the last play that he ever solely conceived. The plot structure and relative staging of the play seem to be more or less Shakespeare’s invention, contrasting his usual borrowing of other common dramatic devices. As Prospero uses his textual knowledge to shape the natural world around him, so has Shakespeare apparently shaped the structure of this play to something entirely new and efficacious.

Despite this parallel, several critics have renounced the concept of Shakespeare’s final play being autobiographical. Rather than looking for the “inner meaning” underlying the play, scholars like Elmer Edgar Stoll argue that interpretations that look for any message not already present in the text “trouble” and “disturb . . . the artistic effect” (26). This school of thought warns readers of the dramatic text to not insert messages where Shakespeare intended none simply because the play was the last one that he wrote. Stoll’s argument denounces the concept of Prospero being a dramatized version of the playwright: “And Prospero is not Shakespeare any more than (as fewer think) he is James I, except in the sense that the dramatist, not the Scotch monarch, created him” (25). Stoll goes on to describe how readers must take into account the “reality” of this play. Despite its fantastic spectacle, the true power of the script lies in the humanity and relatable nature of each of the characters. This reality extends especially to the characters of Ariel and Caliban who are certainly supernatural but only proportionately so to the human condition: “For, above mankind (or, in Caliban’s case, beneath it), these creations are, though fashioned after its similitude” (26). These spirit and half-demon characters were intended to be played by human actors after all; it follows that their supernatural existence extends from a human perspective.

The End of Magic

To put it briefly, Shakespeare’s The Tempest is as equally ever-changing and powerful as its title metaphor. While the play begins with anger and chaos, it ends with forgiveness and resolution. This intense shift in play dynamics in only four hours can be attributed to the layers of metaphor that tie the piece together. As magic quickly changes the natural world around these characters, so does metaphor and language change their way of understanding this world around them.

But what is the significance of Prospero’s discarding of his staff and book? Some scholars find this action to be a final farewell to the island by Prospero, or perhaps Prospero wishes to do away with the magic that brought him to the island in the first place. Since the power of language so closely ties into the power of magic (and the power of drama) in this play, one can understand that this is the result of Prospero’s motivations shifting from selfishness to compassion. Rather than using magic and words to control those around him, Prospero has chosen to control his own, selfish desires in order to rejoin the others in mutual trust. And yet the play remains magical and mysterious throughout the ending as the words of the play hang fresh in the air. John S. Mebane comments on this concluding moment as one that represents the whole of the magic within the play: “Prospero’s abjuration of his art . . . underscores the ambiguity of magic in The Tempest, a mysteriousness which is appropriate . . . for a work which reveals the ambiguities of life itself” (Renaissance Magic and the Return of the Golden Age, 179). As spectacular and supernatural as this play is, the genre of drama endows the piece with a physical significance that is difficult to ignore. This relatable feature is the result of the magic that comes from a lifetime of work in both the word and stage of theatre. What is magical and ephemeral is embodied by the simple and corporeal, and by this construction, Shakespeare’s fleeting farewell lives on in permanence.

Works Cited

Brown, John R. “Introduction.” Introduction. The Appluase Shakespeare Library: The Tempest. By William Shakespeare. New York: Applause, 1996. Ix-Xix. Print.Collins, Michael J. “The Tempest by William Shakespeare.” Theatre Journal May 37.2 (1985): 222-24.

Brower, Reuben A. “The Tempest.” Ed. Hallett Smith. Twentieth Century Interpretations of The Tempest. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969. 94-114. Print.

Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge, England: Cambridge UP, 1995. Print.

Mebane, John S. Renaissance Magic and the Return of the Golden Age: The Occult Tradition and Marlowe, Jonson, and Shakespeare. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1989. Print.

Shakespeare, William. The Norton Shakespeare, Based on the Oxford Edition. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt, Walter Cohen, Jean E. Howard, Katharine Eisaman Maus, and Andrew Gurr. New York: W.W. Norton, 2008. Print.

Stoll, E. E. “The Tempest.” Ed. Hallett Smith. Twentieth Century Interpretations of The Tempest. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969. 25-33. Print.

Quiller-Couch, Arthur. “The Tempest.” Ed. Hallett Smith. Twentieth Century Interpretations of The Tempest. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969. 12-19. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

It was fun to read this and reminisce about one of my favorite Shakespeare plays. I’ve learned about the parallels between Shakespeare and Prospero before. They are both aging men living in a time of exploration and who use words as power. But it is still fun to consider playwrights in general to be wizards… By using magic, Prospero wields so much power over the other characters and the play’s conclusion. His big plan is to return home with his daughter securely married into royalty, even if it means giving up his glorious power that made it possible. The difference is that people feared Prospero for his power-he could not expect to live a life of peace in a community while still practicing magic. Then again, I suppose what you wrote back then could be a lot more dangerous too. But really, it is his selfishness that he is giving up…his ability to focus on his family’s future.

Honestly, I was disappointed with The Tempest. There was so much potential in this one, but it was as though Shakespeare, “The Man,” was giving up. Great premise, great setting, great characters with witty dialogue, but why, Prospero? Why do you relent so easily? Ferdinand, what do you see in Miranda? What was the point of it all, Shakespeare? It wasn’t clear. These characters just could not convince me of this world.

The ending was classic. C-L-A-S-S-I-C. It seems “The Man” knew he was retiring. Having the magician, Prospero—possibly a reflection of Shakespeare himself—address the audience was brilliant. He explains his mission was to entertain, begs pardon for all his wrongs, and asks to be set free. Loved it.

If only the rest of the play could have been so affecting and clever. Nonetheless, I thank The Man for his entertainment, forgive him his wrongs, and set him free. Run, Shakespeare run.

I read “The Tempest” for a discussion group meeting. It is always beneficial to read a Shakespearean play and then discuss it with others. Furthermore, I have a goal to read at least two Shakespearean plays each year so reading “The Tempest” helps in meeting my goal.

I found this play to not be one of Shakespeare’s better stories. I have enjoyed and learned more from other plays. In my perspective, this is a tale of revenge and ultimately forgiveness and reconciliation.

The main issue I had with this play was the concept of love at first sight; Miranda and Ferdinand fall in love the second they lay eyes on each other. Let’s keep in mind that Miranda has only laid eyes on two men: Prospero, her father, and Caliban, her servant. No matter how good looking Caliban was, I can’t imagine he was very clean, so when a somewhat well groomed Ferdinand appears of course Miranda is smitten. That doesn’t make their love divine or special. Ferdinand just didn’t have much competition.

I do have to give Shakespeare a little credit for creating a strong female character in Miranda. It is she who proposes to Ferdinand. Feminism appears in a Miranda because she hasn’t been exposed to the poisons of societal perceptions and standards.

Between this, Hamlet and Julius Caesar i’d say that this was my least favorite to read, but at the same time I think this would be the best to see performed.

I’ll keep my eyes open to catch a performance of this.

I feel The Tempest really does reflect a review of his career.

I agree! It seems so complicated at first but the more you look at it the more simple it seems.

If I learned anything important from reading The Tempest, then it was how ridiculously jumbled up society can be when you take a step out of it.

I loved it! I’m always very apprehensive about undertaking a Shakespeare play because I’m not great at picking up on his brilliant quotations, however, I just loved it for the play it was meant to be, the character’s are excellent, in particular the character of Prospero who is so complex when interpreting him, is he tyrannical? are his actions justified? (in my opinion, hell yeah!). And the incorporation of the romance between Prospero’s daughter Miranda and Ferdinand (the son of the King, who happens to be travelling with Antonio, who sent Prospero and Miranda away to basically drown. Who knew they’d survive to get their vengeance!

I really disliked everything about play.

Reading this story like most of shakespear’s works it was hard to decipher. I got some of the key pieces of information like the ship wreck, cause and marriage proposal. Then, somewhere in the read I got lost with the dialect.

Nice piece of writing. I think that this play was really nice. It was kind of sweet and it made the play good because Prospero didn’t really hold a grudge.

I love your last sentence. The Tempest really brings to the fore these great themes Shakespeare has explored throughout all his great texts. Especially what I got from your piece was the relationship between the ephemeral and the eternal, the corporeal and the mystical. The artistic power is what gave Shakespeare his eternal status as the greatest English dramatist (perhaps THE greatest) and yet it is in his reconciliation with the human condition in his renunciation of his artistic powers at the end of life that make his works so powerful. Wonderful essay!

Shakespeare’s best written play, in my opinion, even if A Midsummer Night’s Dream is my favorite.

Shakespeare is positively brilliant. He references chaucer for crying out loud. He is amazing.

This turned out super well! Awesome job~ I didn’t really like the Tempest when I read it but, after this, I may be giving it a reread. Thanks~

“The Tempest” is one of my favorite Shakespearean plays mainly because of its exploration of the European encounter with the New World – and especially the character of Caliban, who represents a sort of primal man, or in an oft abused phrase, a “noble savage.”

I take it that you agree with the critics who think that one should not read the play as autobiographical. This is a position I wholeheartedly agree with. After all, the play was written four hundred years ago – what does it matter to me if something in the play pertains to Shakespeare’s actual life? It has to stand on its own, even if it is a dramatic exploration of our historical encounter with the New World. If we were required to know facts about Shakespeare’s life, which are probably as mundane and profound as any reader’s, the play would have little meaning for us in the 21st century.

There is a nitpicky error in the description of the plot: Prospero does not intend to return to Milan, where he is the rightful Duke. Instead, he is going to Naples, in order to witness the marriage of Ferdinand and Miranda. “And in the morn/I’ll bring you to your ship, and so to Naples,/Where I have hope to see the nuptial…” (Act 5, Scene 1, lines 307-9). And in the Epilogue, Prospero says “Now, ’tis true/I must be here confined by you,/or sent to Naples” (Act 5, Epilogue, lines 3-5).

Thanks for writing about a play which in my estimation deserves much more attention that it usually receives.

You offer an insightful overview of the play here and provide much for consideration. Also of interest to those considering Shakespeare’s influences and sources might be Montaigne’s Essays, which are available in the public domain Cotton translations from Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/3600/3600-h/3600-h.htm.

Of particular note for those considering Shakespeare’s Tempest would be the essay “Of Cannibals” and “Of the Custom of Wearing Clothes,” as well as “Of the Force of the Imagination” and “that the Profit of One Man is the Damage of Another.”

I have always been intrigued, after a few years of reading the Tempest rather intently, by the question of whether the character of Gonzalo seems to be any more or less insightful and skilled than Prospero in the practical wisdom of the political arts. (It was, after all, Gonzalo who saved Prospero and Miranda from what would have been death at his brother’s hands.)

It might also be worth examining Machiavelli in that respect, particularly The Prince (http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/machiavelli-prince.asp), but also his other work (http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/machiavelli-the-historical-political-and-diplomatic-writings-4-vols) in order to consider the extent to which Prospero himself employs what we might call Machiavellian tendencies in his rule of the island’s only other inhabitants, Caliban, Ariel and Miranda.

The fact that he ends the play in a position of substantive power (father to the wife of the heir to the throne) suggests to me that it’s not entirely clear that Prospero’s perspective has changed — only that some of the things he says to the characters imply that he wants them to think that his perspective has changed. I’m also skeptical of how much we can trust Prospero’s renunciation what might be read as the condescendingly deferential tone of the closing speech.

Developing such an alternate perspective on the play would involve recognizing the ambiguity of Prospero’s purposes throughout the play. He never takes vengeance, properly considered: there’s little in the way of retributive justice or punishment undertaken by the King (himself, it would seem, innocent) and his courtiers. The most that he does is scare them. Moreover, it seems that Prospero has a specific purpose in bringing Ferdinand and Miranda together.

Once Prospero has accomplished the feat of joining the two lovers symbolically with a wedding masque and knows that the nobles are scared, he brings them in and seems to forgive without much struggle — as if this either does not represent his actual views at all, or as if it were his perspective all along. Is this all an elaborate game of chess on Prospero’s part?

I’d like to see a bit more treatment of Stephano and Trinculo, who help Caliban appear in more scenes throughout the play and also serve (it would seem) to provide much of the comic relief.

I just recently finished reading The Tempest for a class. At first, I was very skeptical on whether or not I would like it; I normally only read Shakespeare’s tragedies. However, after reading it and numerous critical evaluations of the text, I found myself rather fond of it. Your mentioning of the English language in relation to the play is a common viewpoint from the postcolonial lens that many scholars employ when analyzing the text. For example, Paul Brown states that Miranda’s giving of language to Caliban is an “inscri[ption of] a power relation as the other is hailed and recognizes himself as a linguistic subject of the master language.” I recommend reading Brown’s article if you’re interested in the theme of colonialism and how it relates to the play: http://msuweb.montclair.edu/~furrg/gbi/brown_thingofdarkness_85.pdf

The weird sisters appear in “Macbeth”, not “Hamlet”.

Aurther of this? I’m using you as a cited page plz answer!!!

The setting of ‘The Tempest’ was bordering on the dystopian when looking at some of its elements. What I have always, and childishly so, compared it to is Lord of the Flies. Both portray the use of the hierarchical nature of man when facing an absent state or structural authority, and more so, portray society through how easily it dehumanises itself.

Yes I think that ‘The Tempest’ by William Shakespeare is a really true and good story …💜💛

Although the references used are listed and there are a couple of citations along the article, it feels that several claims need support, like the ones referred to the expansion of the English language and the work of scholars on Shakespeare.