Paper Towns: John Green’s Deconstruction of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl

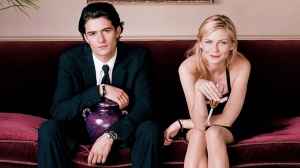

The trope of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl was created accidentally by film critic Nathan Rabin, in a review of Elizabethtown for The A.V. Club in 2007. Rabin used the term negatively to critique the one-dimensional, unrealistic character of Claire, portrayed by Kirsten Dunst. According to Rabin, in addition to being unbelievable and annoying, the character’s largest flaw is that, “The Manic Pixie Dream Girl exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teaching broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures” (Rabin, AV Club). Calling Claire a Manic Pixie Dream Girl was never supposed to be more than a scathing critique, however, the term evolved into a trope that crossed genres from movies to literature.

On July 15, 2014, almost exactly seven years after he first coined the term, Rabin released a statement in Salon Magazine apologizing for this inadvertent invention, saying that, “In 2007, I invented the term in a review. Then I watched in queasy disbelief as it seemed to take over pop culture,” (Rabin, Salon). Since its original reference to Kirsten Dunst in Elizabethtown, the term has expanded and has been used to describe Zooey Deschanel in (500) Days of Summer, Natalie Portman in Garden State, Kate Hudson in Almost Famous, Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and Diane Keaton in Annie Hall, just to name a few (Bowman).

The problem with the use of this trope in popular culture is that, according to Rabin and many other critics, the term is inherently sexist. Manic Pixie Dream Girls were created by the writers solely to help the male protagonist feel more fulfilled; therefore they have no life of their own and cannot exist without the mopey male. This leads to the blatant lack of dimension in these characters and explains why the characters are so unrealistic – there are no women in real life who are Manic Pixie Dream Girls. The “dream” in the name itself implies that it is not a character that can exist in reality, nor should it. At the end of his apologetic article in Salon, Rabin encourages writers to stop the spread of the tropes and to, “try to write better, more nuanced and multidimensional female characters” (Rabin, Salon).

John Green and the Manic Pixie Dream Girl

Many writers have sided with Rabin and taken a stance against the trope, including John Green. In his essay in Salon, Rabin acknowledges a statement from John Green who discussed how the Manic Pixie Dream Girl inspired him to write his novel, Paper Towns, which is currently being adapted into a film. The novel is told from the perspective from Quentin Jacobsen, who has been obsessed with his next door neighbor, Margo Roth Spiegelman, since they were kids. Although Quentin tries to place Margo into the category of Manic Pixie Dream Girl at the start of the novel, the more he learns about Margo, the more depth she acquires, and the less she fits that stereotype. John Green has declared that:

‘[Paper Towns] is devoted IN ITS ENTIRETY to destroying the lie of the manic pixie dream girl…I do not know how I could have been less ambiguous about this without calling [Paper Towns] The Patriarchal Lie of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl Must Be Stabbed in the Heart and Killed’ (Rabin, Salon).

Through the structure of the novel, and Quentin’s process of discovering Margo’s depth, John Green makes apparent the restricting nature of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) trope and the negative effects it has on people’s ability to understand each other.

The Strings

The novel is divided into three parts – The Strings, The Grass, and The Vessel – which reflect the three different metaphors Quentin uses to describe how people are connected in life. In each new section, Quentin comes to a new understanding of Margo. In The Strings, he starts by believing that Margo falls into the one-dimensional MPDG trope, due to how much he romanticizes her, without truly knowing her. Margo is immediately introduced to us as a “miracle” (Green 3), which leads us to believe she is going to represent this fantastical female trope. This is only furthered by nine-year-old Quentin stating that Margo is, “the most fantastically gorgeous creature that God had ever created,” (4). In addition to her otherworldly beauty, Margo has the tendency of showing up outside Quentin’s windows to drag him on adventures, and has an innate understanding of life at just nine-years-old; therefore she is already displaying a quirky side that Manic Pixie Dream Girls inhibit.

As Margo grows, so does the hype around her. She is no longer a one-dimensional female trope only to Quentin; by her senior year in high school she has become a mythical creature, revered, and idolized by the entire school. This reflects that Margo has very little control over her own identity, one of the main aspects of a MPDG. Margo alludes to this lack of control during a late night adventure with Quentin that leads to them standing on the Sun Trust Building in downtown Orlando, staring out at the city in front of them. There is no substantiality in the world around Margo, just like she herself feels unsubstantial:

From here you can’t see the rust of the cracked paint or whatever, but you can tell what the place really is. You see how fake it all is. It’s not even hard enough to be made out of plastic. It’s a paper town. I mean look at it, Q: look at all those cul-de-sacs, those streets that turn in on themselves, all those houses that were built to fall apart. All those paper people living in those their paper houses, burning the future to stay warm (57).

Of course, Margo herself is one of these paper people, and refers to herself as “paper girl” (58), made of something physically one-dimensional to compare to the one-dimensional trope of the MPDG. Manic Pixie Dream Girls are paper girls – they look good in theory, but cannot exist in real life. She tells Quentin that, “The closer people get to me, the less hot they find me,” (38), because people believe that Margo is more perfect from farther away, just like the city of Orlando. People are attracted to the idea of her as a MPDG, opposed to the girl herself. Because the trope is so unrealistic, it can only exist when applied from a distance. Margo is no exception, and the day after making these observations to Quentin, she disappears, putting as much distance between herself and the people who view her as a paper girl as possible.

During this phase of the novel, Quentin uses the metaphor of the strings to explain the human experience. When a person breaks down, it is as if, “all the strings inside him broke” (301). Quentin likes the metaphor that we are all held together by strings and when we fall to pieces the strings simply snap, because it is a simple, direct metaphor. However, it oversimplifies life by, “imagining a world in which you can become irreparably broken,” because, “the strings make pain seem more fatal that it is” (302). The strings are a very simplified view of life – people are either broken or whole. With this metaphor, there is no in-between because breaking down is not a process, but something instantaneous. Just how Quentin uses this oversimplified view of life in the first section of the novel, he has a similarly oversimplified view of Margo, and has no problem believing in a fictionalized, romanticized version of her, despite the nuances missing from this imagined Margo.

The Grass

After Margo’s disappearance, the novel starts its second section – The Grass – named primarily after Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass which Margo left behind for Quentin. Reading it for clues, Quentin begins an epic scavenger hunt thinking he will learn where Margo went. During this hunt, he discovers her as a real, multi-faceted person, through little facts about her that he had never considered in his romanticized version of her. For example, Margo used to camp out at an abandoned strip mall called The Osprey, read Walt Whitman, and had a vinyl record collection, including one of her favorite artists, Woody Guthrie.

Quentin learns more about Margo gradually and periodically, discovering little pieces of her at different times. There is no prophetic moment in which Quentin suddenly comes to understand the universal of Margo Roth Spiegelman because there is no one universal version of Margo Roth Spiegelman. This rejection of a universal truth, often called a metanarrative, is a common theme in deconstruction literary theory. In deconstruction theory, critics believe that because there are so many different facets to life and the human experience there is not just one story that can encompass all of those things at once; therefore they fragment narratives into concrete incidents. These incidents are a more accurate interpretation of specific aspects of the human experience, opposed to the generalized story that tries to capture the whole experience at once in an attempt to transcend narrative (Rivkin and Ryan).

The fragmentation of Quentin’s discovery of Margo is a way that John Green deconstructs the metanarrative of the MPDG. That literary trope presents women with certain overarching features that are not realistic and do not portray any truth about women – just an idea that writers have of them in their heads. By introducing Quentin to new information about Margo in such sporadic ways – sometimes with weeks passing before Quentin can connect clues – it prevents him from creating this transcendental version of her that has no grounding in real life.

During this stage of the novel, Quentin uses the metaphor of the grass to explain the ways people are interconnected and how he can still learn so much about Margo even though she is not physically with him, because their roots are so tangled together. Quentin tells Margo, “The grass got me to you, helped me to imagine you as an actual person. But we’re not different sprouts from the same plant. I can’t be you. You can’t be me. You can imagine another well – but never quite perfectly, you know?” (Green 302). Quentin recognizes that there is a certain extent to which he can know Margo – another argument made by deconstruction theorists. There is a limit to knowledge, and humans can never know something in its entirety. Although we can come infinitely close to knowing all there is about a person by accumulating knowledge and fragmented stories, there is always going to be pieces of people that no one gets to know (Rivkin and Ryan). Not only does this add depth to Margo as a character, but it destroys the trope of a Manic Pixie Dream Girl on a whole. It shows that every human being has many different levels – some which will remain completely unknown – thereby discrediting the one-dimensional MPDG. Even the heading on the back of the book, “Who is the real Margo?”, implies that Margo is multifaceted and that people have their own interpretations of her, opposed to being a one-dimensional figure who is everything to everyone, transcending description.

The Vessel

In the third section of the novel, Quentin and his friends start on an epic, twenty-one hour road trip from Orlando, Florida to Agloe, New York – a town that used to exist only on paper where Margo has been living since her disappearance. Agloe is a “paper town” that existed solely on paper as a protection against copy-right infringement. However, since people continued to search for this paper town, someone finally put up a store where the town would have been, making Agloe real.

When Quentin asks why Margo chose Agloe, of all places, to go, Margo’s response shows exactly how direct John Green is in his dislike of the MPDG. Margo explains that when she stood on top of the Sun Trust building with Quentin, she was not thinking about how Orlando was made of paper but herself as well:

I looked down and thought about how I was made of paper. I was the flimsy-foldable person, not everyone else. And here’s the thing about it. People love the idea of a paper girl. They always have. And the worst thing is that I loved it too. I cultivated it, you know? Because it’s kind of great, being an idea that everybody likes. But I could never be the idea to myself, not all the way. And Agloe is a place where a paper creation became real (Green 293-294).

Although, in this passage, John Green alludes to the appeal of the MPDG, he shows what a negative affect that the image has on Margo. She recognizes herself as flat, and one-dimensional in the eyes of others, and wants to grow into someone more substantial – something she feels she cannot accomplish in a paper town like Orlando, which is why she felt she had to disappear. When Quentin and his friends reunite with Margo, they call her selfish for disappearing without any warning. However, it is this selfishness that helps Margo start to break out of the trope of the MPDG. Since Manic Pixie Dream Girls exist solely for the purpose of the male protagonist, by leaving the male protagonist behind, Margo establishes her own sense of self which continues to grow in her time in Agloe.

This concept of the perceived person opposed to the person’s individual identity leads to Quentin’s discovery of his metaphor of the vessel. According to this metaphor, every person starts off as an airtight vessel that gets cracked and battered over time. He asks Margo, “When did we see each other face-to-face? Not until you saw into my cracks and I saw into yours. Before that we were just looking at ideas of each other…But once the vessel cracks, the light can get in. The light can get out” (302). By admitting that he has flaws and that Margo has flaws, Quentin is able to have the deepest understanding of Margo he achieves in the novel, because by seeing her weaknesses, he sees her for herself. He acknowledges that, at one point, she was just an idea to him – his own Manic Pixie Dream Girl.

As Quentin discards the version of Margo he invented for the real Margo, John Green discards the Manic Pixie Dream Girl from literature. The readers have discovered Margo in the same way that Quentin has, and have realized her depth over time. After discovering the power behind a character as multi-dimensional as Margo, Quentin and the readers feel a sense of shame for having originally viewed her with such a narrow and limited perception. John Green makes his audience acutely aware that characters like Margo, who has depth and a sense of self is the more effective in communicating the human experience, opposed to a quirky, ukulele-playing, fairy princess who likes to dance in the rain.

Works Cited

Bowman, Donna, Amelie Gillette, Steven Hyden, Noel Murray, Leonard Pierce, and Nathan Rabin. “Wild things: 16 films featuring Manic Pixie Dream Girls.” A.V.Club.com. Onion Inc., 4 Aug. 2008. Web. 10 Nov. 2014.

Green, John. Paper Towns. New York: Speak, 2008. Print.

Rabin, Nathan. “The Bataan Death March of Whimsy Case File #1: Elizabethtown.” A.V.Club.com. Onion Inc., 25 Jan. 2007. Web. 10 Nov. 2014.

Rabin, Nathan. “I’m Sorry for Coining the Phrase ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl’.” Salon.com. Salon Media Group, 15 Jul. 2014. Web. 10 Nov. 2014.

Rivkin, Julie, and Michael Ryan. “Introductory Deconstruction.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. 2nd ed. Ed. Rivkin, Julie and Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004. 257-261. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I recently read “Paper Towns” after a friend told me that John Green wrote the book attempting to destroy the Manic Pixie girl trope. I loved the book! Your article was great! Your analysis was insightful and concise. Great job!

I must say I love how John Green writes interesting girls with actual minds and thoughts, instead of atractive female bodies with lame, cheesy ideas and that only care about love, boys and clothes. I love how little Margo was the one that wasn’t afraid of the dead body, because writers tend to write scared, shy and fragile girls, but not John Green. He sees women and children as actual people rather than the stereotypical characters with the expected “normal” reactions.

I’m in the middle of re-reading A Separate Peace and I’m convinced that Finny is a Manic Pixie Dream Boy.

I like the approach Green took to attack the trope. He could have done it in loads of different ways. But he chose to basically build Margo up as a manic pixie dream girl, only to reveal in the end that it’s all just been in Q’s head.

I have absolutely no idea what so many people see in this book. I did not like it in the least. While I give high praise to anyone who can create their own world inside their head, some who are capable of doing so are incapable of writing. It’s possible that I am being rude, but I must say it. In my opinion, John Green cannot write. This is the only book that I have read by Mr. Green, and I do not intend to read another.

You know, we’ve always been told that a great plot can make up for lack-luster writing. Sadly, this book contains neither an excellent plot nor phenomenal writing.

I thought I’d hate Margo, but I didn’t. In fact, she was probably my favorite character.

Greens approach was very interesting. While the book was not to my liking, I can certainly understand why people are followers of Green and his novels. He provides young reader with highly developed characters and breaks the mold of conventional young adult novels.

I didn’t even know about the “Manic Pixie girl” thing until I read your article. Very interesting stuff!!! I must pick up a copy of Paper Towns

The whole point of the book is: don’t be a flimsy, paper girl like Margo was. Everyone had their own little oragami shape of her, none of which was who she truly was.

Paper Towns was, like all of the John Green’s books, a work of art filled with existencial questions and sentences made of profound meanings.

This book was breathtaking. It isn’t one of my usual reads but it was very refreshing. It kept me reading so much and I loved he storyline despite being slow at times.

I’m a huge fan of John Green and I think he often writes exceptionally complex young characters. I really appreciate how you’ve laid out Margo in Paper Towns and how she challenges the MPDG trope. However, I feel like Green doesn’t always dismantle the trope in his work. I think sometimes he just lets the MPDG stay that way. For example, I feel like Looking for Alaska is a total manic pixie dream girl story. Strange considering how strongly he seems to feel about it…

I agree! When I read Looking for Alaska, Alaska really seemed to me like a MPDG. However, things don’t end particularly well for Alaska, and I think that her MPDG-ness is a contributing factor to that. However, because Green is dealing with the huge topic of mortality, it seems like his feelings about the MPDG take a backseat.

I disagree with what you said about Alaska being a manic pixie dream girl. When Pugde found out about what had happened to Alaska’s mother, he saw that she was indeed not perfect, but flawed. Pudge saw that she was simply human but, unlike Q, Miles had continued to see her as perfect I think. Even with her flaws. But the way Pudge perceives Alaska shouldn’t change the way the reader does; flawed and imperfect and therefore, not much of a MPDG.

Loved this article and the insight from Green on his motive of destroying this idea of the Manic Pixie Girl.

In the end I wish I never knew the end because I’d rather know Margo as the fun, adventurous, wondrous, magical creature that she made everyone think she was.

I’d never heard of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl and was flabbergasted by the whole concept. Then, I started looking at my favorite books. And movies. And songs.

It’s kind of mind-boggling how frequently this trope appears in popular culture doesn’t it? It’s one of those things where, once you recognize it, you start to see it everywhere!

I can see how Margo (or, more appropriately, Alaska in LOOKING FOR ALASKA) could be seen as a MPDG at first, but I don’t think they take on that role primarily. Sure, they do bring out the adventurer in the main character, but they’re so much more than that. They have other levels, and other motives, and I like that. It makes them more real, and less dream-girl.

I wish Margo would have come back for Q but I understand why she couldn’t.

I learned that I don’t want to just live in a paper town with paper people- I do want to have some excitement in my life.

This is a great article written about a great book. I read the book last Summer and loved it, though I didn’t engage it quite on the same level that you did. After reading your analysis, I was able to look much more deeply into it, and I found myself greatly appreciating the approach that Green took with this character. Happy endings are easy, and you would expect one, after such an epic quest, but the reality of the situation is that they don’t always end the way you want, or expect, them to. That’s just life. I don’t agree with the sexist implications of the MPDG as I believe that the role can apply to either gender, and can serve to provide the reader and the characters with a lesson, not just false hope and shot expectations. Everybody has something deeper inside of them and we must be willing to look for that and not just take them for granted. This novel justifies that, and I wish that more stories would do the same.

I really like the message of this novel as well! And interestingly enough there have been some critiques that Gus from The Fault in Our Stars is actually a Manic Pixie Dream Guy, so the trope can definitely apply to gender.

Q’s character growth was a real treat, and I applaud John Green for making this book about him, not about Margo.

I would love to get into John Green’s books, but for some reason I have a hard time choosing them first when I’m at a book store.

I’m not a huge fan of John Green – if I’m honest I find him fairly cliche. However, your insight on his deconstruction of the manic pixie girl dream might just convince me to give him another shot!

More depth she may have, as writers add sympathetic traits to their pixie girl’s character, but she is always winningly cute. Not so for the sensitive, withdrawn male of the story. He can be pudgy, awkward, tongue-tied, cowardly, whatever. He always seems to merit getting the pixie girl. What’s with that?

Exactly. Her character has more dimension than the stereotypical MPDG but those dimensions are basically just added layers to the pedestal of what still amounts as male idealization: “gee, golly, look at how emotionally self-aware and philosophically probing and deep this teenage girl is.”

It’s a reminder to all of us to withhold judgment until we’ve seen the world through their eyes.

I have always loved this novel and this is one of the many reasons why, but there’s something I can’t help but wonder now after reading this. The novel invites its readers to be on Quentin’s side so thoroughly – he is the protagonist, after all, even if it could be argued that Margo receives just as much development and depth, if not more so – that I have to wonder, couldn’t some readers possibly miss out on this total destruction of the MPDG and cling to the loyalty they feel to Q? I’ve unfortunately read some rather unfair responses to the novel that believe Margo’s selfishness is her defining quality and that therefore she embodies a whole other kind of reductive female trope.

In any case, great work here! A truly thorough and well thought out analysis.

Green’s work is instrumental in making readers realize the distastefulness of the MPDG. This is an excellent analysis of Paper Towns’ subtleties and deeper meaning. Well done!

Awesome article with some really interesting points. The quotes you used really helps solidify your main idea. Great job.

Really intriguing article. It’s great to see that there is such complexity in a popular young adult novel. So often, the two don’t go hand-in-hand. Reading this actually makes me want to read the book. Great job!

It always annoys me how Zooey Deschanel ALWAYS plays a manic pixie dream girl. I love that there are people out there shattering this sexist stereotype in films.

I’d say Paper Towns is effective and a fun movie that mixes teen romance with a road trip that keeps things quirky and clever and cute and so on. It’s a warm crowd-pleaser, and the climax is probably the best part of it all, which is great.

I really liked this interpretation of Paper Towns, it makes me want to return to the book after many years.