“Cultural Labour”: The Fabricated Fantasy of NYC Fashion Culture

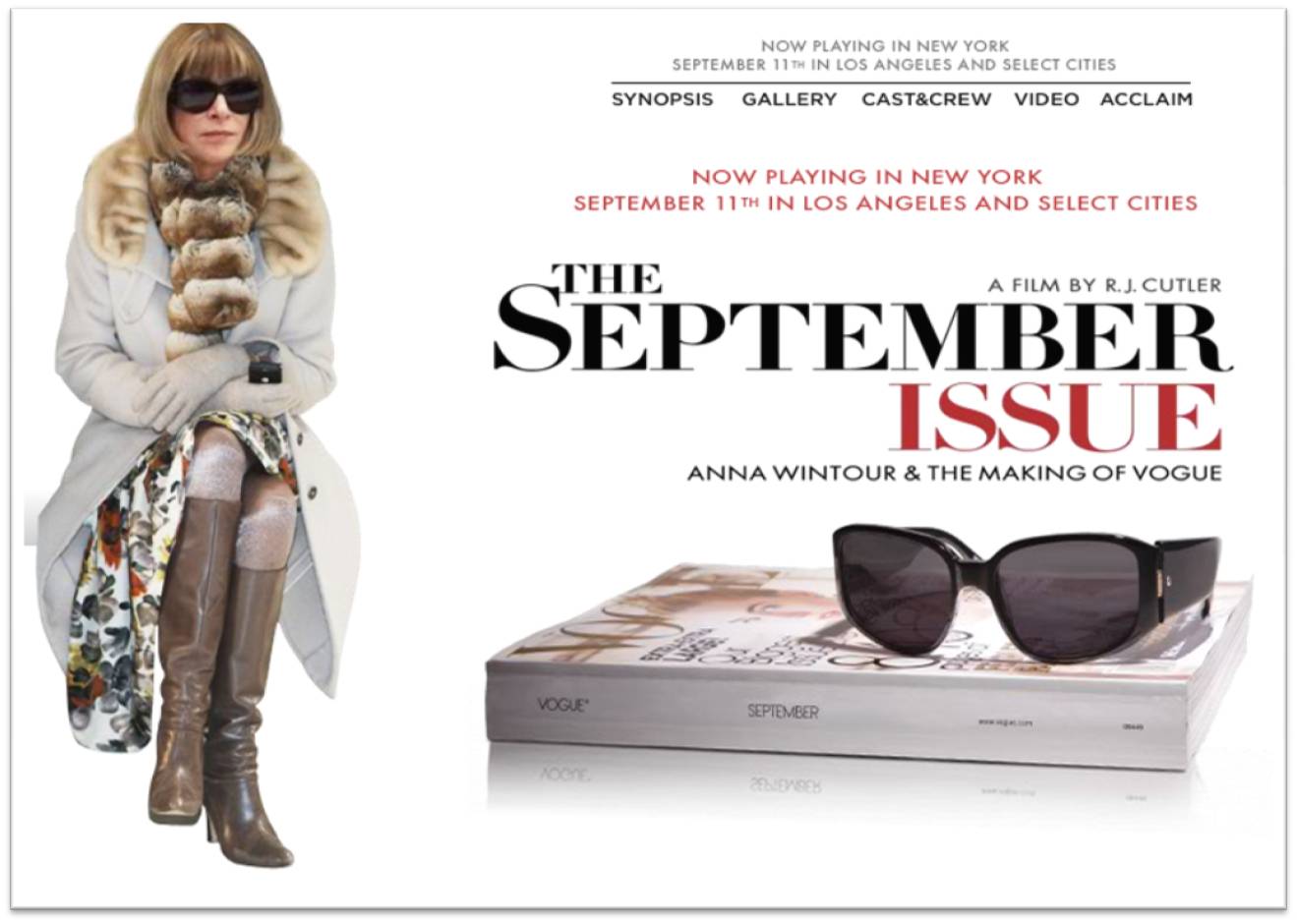

R.J. Cutler’s documentary, The September Issue, represents the “cultural labor” of producing Vogue magazine as Anna Wintour travels around New York City, Paris, and Rome in the back of a limo to meet with fashion designers and decides what is in and what gets thrown out. Cutler’s film glamorizes the work of creating Vogue magazine, and essentially New York fashion, by concentrating on the daily routine of the magazine’s wealthy editor-in-chief and other key figures, such as the creative designer Grace Coddington. In the film, the “labor” and contributions made by the editor, editor-in-chief, creative director, marketing director, and other directors are presented as all it takes to create the magazine, when in fact there are other important overlooked workers, such as interns, sample-makers, and assistants who bend over backwards to help produce it. Instead of focusing on the work of what Christina Moon, in her essay From Factories to Fashion: An Intern’s Experience of New York as a Global Fashion Capital, identifies as the “new kind of workers,” who perform the “cultural labor” essential to a major fashion magazine and culture, The September Issue glamorizes the experience of working for Vogue magazine as traveling around the world, having breakfast with CEOs of major fashion companies, and meeting with top fashion designers.

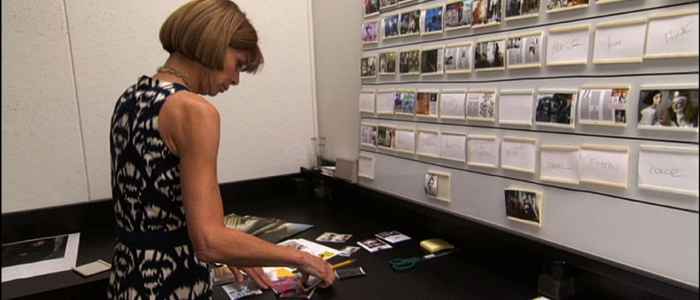

The “labor,” if it can even be characterized as such, portrayed in Cutler’s documentary consists of Anna Wintour going from office to office, place to place, country to country, deciding what photographs, designs, fabrics, styles, and other elements of the magazine are in and which are out. She travels around the world meeting with designers, such as Stefano Pilati, the head designer of Yves Saint Laurent and Oscar de la Renta, to view their collections and either give her approval or dismiss their designs with her legendary sneer. In the film, Candy Pratts Price, executive fashion director of Vogue, says, “Vogue is always going to be Anna’s point of view.” Based on the film’s representation of the work needed to produce the magazine, Price is right (Cutler, The September Issue). After every photo shoot, Anna Wintour looks over the photographs and decides what photographs are in and which ones are out, without any consultation with her employees. Despite Coddington’s dissatisfaction with some of her boss’s—and long time friend’s—decisions, Anna Wintour’s words and opinions are what goes at Vogue; as Price notes, “Vogue is Anna’s magazine” (The September Issue). The film does not, however, capture the work of the behind-the-scenes people such as interns, assistants, and sample-makers, who perform the “cultural labor” necessary to produce the photography, design (i.e. clothing texture, fabric), wardrobes and accessories for photo-shoots, visual and textual editing, etc., that are delivered and ready for Wintour to judge as satisfactory or unsatisfactory.

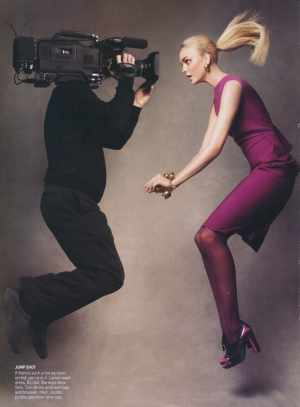

In addition, The September Issue contains footage of the work of creative designer Grace Coddington as she comes up with ideas for photo shoots, and outfits for models, and also styles the clothing on the models during the various photo shoots. She is in charge of a photo shoot in Rome and in Paris, as well as the color-blocking shoot for the magazine in New York City. The film captures Coddington as she is basically forced to re-shoot the color-blocking photo shoot, after Wintour decides she doesn’t like the photographs from the first shoot. Coddington is stressed, but thinks on her feet and comes up with a brilliant idea that involves the camera crew of the film. The footage of Coddington’s work as creative designer is the closest the film comes to capturing the “cultural labor” of producing Vogue magazine. Christina Moon, however, in her essay From Factories to Fashion: An Intern’s Experience of New York as a Global Fashion Capital, defines such “cultural labor” as the work of “the interns, models, front-office workers, design assistants, and sample makers—the new kind of workers who work hard to create not just garments, but fashion” (208). Thus, the interpretation of “cultural labor” in the film is a stark contrast to the labor Moon discusses in her essay.

Moon details the daily duties of “an ethnically diverse group” of immigrants working as sample-makers for “various design corporations in the district” and explains how the loosening of United States immigration laws and migration of immigrations in 1965, and from the 1970s onwards, vastly affected the transformation of the New York-based garment industries (197/198). The Asian and Latin American garment workers who arrived in New York City in the late 1970s are now the sample-makers of corporate design sample rooms. In discussing the history of these immigrants in relation to the emergence of “a new kind of ‘American’ worker in garments,” Moon shed’s light on the decade-long importance of these “highly skilled workers” to the development and creation of New York fashion (198). In addition, Moon describes the behind-the-scenes work of the various interns, the role of factories owned by Korean and Chinese entrepreneurs (specifically Esther and John’s factory), and the complex division of labor that developed as a result of the industry’s need for workforces of cultural workers. The work of these factory owners and workers, interns, front-office staff, and Latin American and Asian sample-makers is the “cultural labor” that keeps the New York fashion industry alive and thriving. Moon illuminates the crucial role these workers play in creating new forms of production and creative practices that are essential to the ceaseless changing and operating of New York City as the “fashion capital of the world” (202).

In highlighting the influence of the “cultural labor” carried out by the behind-the-scenes workers in New York fashion, Moon implicitly critiques the ways in which twenty-first-century popular culture glamorizes all aspects of labor associated with and necessary for New York Fashion Week, as well as the city’s fashion culture as a whole. Her criticism is validated by the presentation of the labor of producing Vogue magazine in R. J. Cutler’s documentary, The September Issue. The film did not feature the interns running errands, the front-office workers answering phones, the sample makers operating sewing machines working to “translate the designer’s imagination, manifest in a sketch, into three-dimensional material reality,” or the design assistants crafting new product ideas or scheduling and organizing things to ensure that projects are finished in time for meetings and sales (Moon, 197). Instead, the film documented the daily routine of editor-and-chief Anna Wintour, as she leisurely traveled around the world meeting with various high-fashion designers and voicing her harsh, unchallenged opinions.

The September Issue features Anna Wintour strutting about the New York City Vogue offices like a dictator declaring yes or no, when presented with various components and options for publishing that are created by behind-the-scenes workers, (i.e. interns, design assistants, front-office workers, sample makers, etc.), who spend hours perfecting all the pieces that are going to be either trashed or approved (most likely trashed, by Anna Wintour). This is an extremely unrealistic representation of what it is like to work in the New York Fashion industry. Through the films idealization of the labor of producing Vogue magazine and representation of the lavish, elite life of Anna Wintour as typical for a woman working in fashion, the true arduous “cultural labor” needed to produce the magazine, performed by the interns, sample makers, assistants, etc., is minimized, discounted, and disregarded.

In addition, the film’s depiction of race, class, gender, and nationality suggests that New York fashion-based culture is limited to white upper-middle class women and controlled by white elite French and American women. In the film, Wintour and Coddington, through mostly Wintour alone, completely control the production of Vogue magazine; ironically, both women are wealthy, white, and British. Other important figures featured in the film are Candy Pratts Price (executive fashion director), Andre Leon Talley (editor-at-large), Tom Florio (senior vice president publishing director), Tonne Goodman (fashion editor), Sally Singer (feature director), and Virginia Smith (marketing director). In terms of race, class, and gender, all of the latter employees are white, well-off American women, except for Andre Leon Talley, a wealthy African American man, and Tom Florio, a wealthy white American man. The directors and editors of Vogue magazine presented in R.J. Cutler’s documentary reveal a pattern in the “type” of person who embodies and represents New York City fashion culture and production. These “type” of people are white affluent French or American women and men (mostly women).

The affluence of these “types” of employees is apparent not only in their expensive lifestyles (i.e. clothing, accessories, transportation, etc.), but also in the power of their positions as leaders of the production of a major women’s fashion magazine—a magazine that has acted as prime fashion advisor New York City’s elite since its creation in 1892. Furthermore, the New York fashion-based culture represented in The September Issue is defined according to the lives and work of the prosperous white women and men in charge of major fashion magazines, departments, and companies. The scenes that show Anna Wintour’s mansion on Long Island and an interview with her daughter capture her luxurious existence as the most influential editor-and-chief of Vogue, while at the same time they enhance the film’s idealizing of the lives and “cultural labor” of those who work in fashion. The September Issue succeeds in maintaining Vogue’s reputation as the guiding voice in high-society fashion for New York’s social elite by glamorizing the labor of producing the magazine and presenting only the wealthy white American and French (for the most part) female directors, editors, and editor-in-chief.

A particular section of Cutler’s documentary that demonstrates its promotion and glamorization of the life and work of the wealthy white men and women working in the industry is the scene of the Vogue Retailers Breakfast. This annual gathering of high-end department store heads is held in Paris at the Ritz, a five-star prestigious luxury hotel. Anna Wintour arrives at the breakfast wearing a light brown Chanel jacket and skirt lined with brown fur on the collar and cuff of each sleeve. Her tall brown leather boots, large sunglasses, and elegant diamond necklace add to her extravagant fashion ensemble. The business breakfast is held in a large room at a long oval table set with various dishes. The table is covered with a fancy tablecloth, and a row of exquisite flowers runs down its center, contributing to the ostentatious atmosphere. There are about thirty men and women sitting around the table with a copy of what appears to be a book of information to guide the discussion. All of the men and women seem to be in their late thirties to late fifties, and they are all, with the exception of Andre Leon Talley, white. The men are wearing classic suits and ties, while the women are dressed glamorously in business-appropriate attire; most of the women’s outfits in this scene are not as fancy and prestigious as Wintour’s Chanel ensemble. The formal setting and dress suggest that this meeting or breakfast is an important business event.

However, the tone of the “business,” or breakfast, conversation is surprisingly casual in comparison to the pretentious outfits and highly decorative set-up of the room. The discussion of business, fashion trends, and clothing fabrics is similar to that of a group of friends catching up and having breakfast together. The various retailers, editors, and head representatives of the fashion industry are laughing and enjoying each other’s company, while also being served by waiters in black and white suits. Anna Wintour, “the ice woman,” laughs at and jokes with the CEO of the Neiman Marcus Group, Burton Tansky, when he asks her to help his department with the issue of late delivery of merchandise. Her sarcastic response, “Well what do you want me to do? Rent a truck?” makes it seem as if fixing an issue in delivery is so far beneath her, in terms of her work as an editor-and-chief of an elite fashion magazine (Cutler, The September Issue). Tansky asks Anna to use her influence with the designers to make the designers aware of the rapidly expanding worldwide demand for their product; thus if the designers do not keep up with the production, then the demand will outstrip the supply, and deliveries will arrive late. His request is reasonable, and Anna Wintour can easily help solve the problem by using her authority, and essentially control, over the designers. This scene in The September Issue validates Moon’s criticism of popular culture’s glamorization of the work involved in creating and maintaining New York fashion-based culture. The informal tone of this supposed business meeting, or breakfast, starkly contrasts with the extravagant attire of those present and the ostentatious appearance of the room at one of the most expensive, grand hotels in Paris. This “annual gathering” can hardly be classified as work, let alone “cultural labor.”

The film’s glamorization of the labor of producing Vogue magazine (and essentially New York fashion culture) creates, as Moon says, a “vast disparity between the image, the behind-the-scenes images on television, and the behind-the-scenes experiences of working in the district,” and it influences “our understanding of what gets defined as labor in fashion production (Moon, 208). The “annual gathering” of Vogue retailers shown in Cutler’s documentary is a perfect example of the disparity created between the reality of the “cultural labor” of producing a New York fashion magazine and the fantasy constructed by popular culture that inaccurately defines labor in fashion production according to the duties and luxurious lifestyles of head employees. The directors, editors, and designers featured in The September Issue are, for the most part, all affluent white American or French women, which suggests that class, race, gender, and nationality influence one’s position in and the operation of the New York-based fashion world. The documentary’s focus on the exclusive, lavish life of wealthy white women editors, directors, and editor-in-chief implies that New York fashion culture is created and controlled by a group of social elites. The latter is one of the many fantasies produced by the representation of fashion through popular culture, which is not the least bit accurate in portraying or defining the labor involved in fashion production.

Works Cited:

Moon, Christina. “From Factories to Fashion: An intern’s experience of New York as a global fashion capital”. The Fabric of Cultures: Fashion, Identity, and Globalization. Ed. Eugenia Paulicelli and Hazel Clark. London and New York: Toutledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2009. 194-209. Print.

The September Issue. Dir. R.J. Cutler. A&E IndieFilms and Lionsgate Films Inc., 2009. Film.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

This is a very interesting observation and one that is very much appreciated. The element has been established and is firmly planted; it will continue to grow and prosper as long as it is fed by a healthy stream of revenue. A.k.a. “Don’t hate the playa’ hate the game.” Thank you Morgan..

Thank you for your kind comments :).

My fashionable daughter insisted that my wife and I watch this movie. I liked it very much even though I am not into fashion.

It is difficult to refrain from comparing Anna Wintour to the character of Miranda Priestly.

Anna Wintour OBE is perhaps one of the most powerful women in the fashion industry without being a fashion designer or a model.

As someone who doesnt know that much about the fashion industry, but is very interested in creativity of any form, i was really hoping this documentary would give a good insight into the importance of the magazine (and sept issue) in relation to the fashion industry.

But all that it really seemed to boil down to, is that there are about 1 million readers, who will blindly go out follow the trends in this one magazine, and I, ANNA WINTOUR, Queen of Narnia/Wicked Witch of the Upper West Side, will be the one who decides what they copy…and my decisions will be based on comments such as “it needs more colour!”…huh???

I like the “outsider” perspective that you have given to an industry that is sometimes shrouded in mystery and other times shrouded in glamour and spectacle. You have done a good job exposing the plight of many of the workers as well as giving fair treatment to your source essay. Good job!

Thanks so much, I really appreciate the compliment :)!

vogue: pretensious crap in a sad western culture

In brief, the fashion industry needs to advertise in order to increase consumption. Just like MacDonald’s doesn’t rely on customers deciding for themselves to buy their food; they create specials, toys with purchase, movie tie-ins, seasonal offerings (the St. Patrick’s Day green mint-flavored milkshake, unavailable year round), anything to make people think of their product and desire it.

Yes. Fashion is just clothing, a necessity. It’s a big industry in the USA and provides employment to thousands of people. To increase the amount of money people would spend if they just replaced worn-out goods and bought necessities, the advertisers created luxury goods (status), new designs (fear of appearing unsavvy of the trend), clothes which work together or are easy to care for (convenience and time saving), flattering styles (beauty)… It uses the same points as any salesman and appeals to the human desire for change (and status and attractiveness and competition, etc.).

Even isolated, primitive cultures without fashion magazines enjoy creating adornment. The designer/fashion magazine culture is no more hysterical and self-conscious than, say, the tobacco industry.

Vogue is just a bunch of photos of models wearing garish costumes that are inaccessible and irrelevant to the majority of the population.

timing

The September Issue is one of the best, most insightful and candid looks at the ONLY magazine that matters in the fashion world: VOGUE, honey! *SNAP*!

She’s obviously an excellent editor and well-respected.

When I heard about The September Issue, I was excited and a teeny bit sceptical. However, I was not disappointed in the slightest.

There are so many marvellous things about the documentary.

Anna Wintour wears Prada.

I felt turned off completely by this documentary- the entitlement, the implied nepotism (wants daughter in the industry) etc.

I was most struck by Anna W…walking from place to place, person to person with a constant ‘puss’ on her face. Always ready to dish out demeaning and cutting remarks.

This is a very pertinent and relevant article, and it certainly reminds one of the entire premise of “The Devil’s Wear Prada.” As a general life lesson, sometimes it’s hard to forget that the individuals who receive the glory perhaps do the least amount of actual work. With this being said, I would be interested in learning more about how Wintour became who she is today. Was she privileged? Or did she earn her spot? Or a little bit of both? There’s always more than one side to the story, and so perhaps the documentary missed the other side.

She is enigmatic, but not inhuman.

Long live the Queen.

This article is shocking but not surprising. There have been many movies and shows glorifying these situations and jobs and they perhaps make us aspire to something that isn’t real. That is, of course, with most television. Almost everything is fabricated or glorified and it’s disappointing when we begin to desire unrealistic things for ourselves.

Most of us won’t wear designer gowns but we have to admire the presentation to make us want to spend money to look like a fashion model.

The September Issue is a breath of fresh air which I watch time and time again when I want to laugh, cry and be inspired.

The documentary is a great look into how Vogue,Coddington, and Wintour balance the responsibility of guiding the fashion world and its loyal followers into the next adventures.

While I’m not a fashion fanatic, I did watch Devil Wears Prada and I was interested to find out more about the enigmatic Anna Wintour. This movie only skims the surface of life at Vogue.

Its interesting you mention Devil Wears Prada, its another movie that really fabricates what it is like to get a job in the fashion or entertainment industry. I never understood how movies based in major cities such as NYC show people in entry level positions living lavishly. I lived in NYC for 10 years and getting an entry level position is extremely difficult when you do get one, you usually live in a teeny tiny apartment and you are lucky to break $10-14 an hour in such industries as an assistant to someone when you are so junior in their eyes…i wish a movie/documentary would show cut throat sides of these industries a little bit more.