The Complex Lessons of Environmentally-Motivated Animation

In recent decades, Disney, Pixar, and other animated offerings have become known for delving deep into adult-size issues while remaining family-friendly. However, maintaining the balance between entertaining audiences and sharing important messages becomes more difficult when the topic is narrow and specific.

The early 1990s provided great examples of this pitfall, as well as an overall cautionary tale. As the new decade took off, environmental issues came to the forefront for kids and adults alike. Global warming, the greenhouse effect, and the dangers of deforestation and nuclear weapons were big parts of current events. Kids born in the late 1980s had parents who lived through the Cold War and practiced “duck and cover” drills at school; now, those kids were being told their planet might disintegrate because of acid rain, air pollution, and over-dependence on oil, coal, and gas. Everyone from scientific experts to presidential candidates had new, grim reports and predictions seemingly every day.

Such a climate left animation ripe for characters and plots centered on environmental issues. Indeed, making an environmental message relatable through sentient animals, earth-conscious humans, and consequences in real time sounds like a good idea. The happy endings found in animation might tone down the darker aspects of environmental issues. Add in bright colors, catchy music, and imaginative settings, and animation seems like the perfect medium to spread the message of protecting the planet.

Indeed, plenty of nostalgic viewers see it that way. YouTube viewers and Reddit subscribers discuss how Captain Planet and the Planeteers inspired them, or how Fern Gully: The Last Rainforest both charmed them and made them sympathetic to the plights of non-sentient or totally fictional beings. On the other hand, many former viewers flock to these and other sites to make fun of environmentally-motivated animation. They claim the characters, plots, and overall writing are too heavy-handed and cheesy, and ask what the creators were thinking. Some reviews of these offerings, like the Nostalgia Critic’s, go so far as incorporating foul language and bathroom humor when describing shows’ or movies’ pitfalls.

Who is right? Well, foul language and bathroom humor may not be necessary, but close analysis indicates the detractors of this animation have a point or two. Environmentalism is a simultaneously broad and narrow topic. Some of its complications are too much for young audiences to process, but every complication feeds into the same issue. Thus, animation creators get the opposite problem–focusing a whole project on one certain issue means it could be too narrow to reach kids and adults outside niche audiences. Thus, the project becomes clunky and laughable if not carefully handled. Even when animators and writers exaggerate something on purpose, the effects can be more negative than positive. In fact, many sources of environmentally-motivated animation (EMA), are so heavy-handed that from the ’90s to now, some parents and guardians didn’t or don’t want their kids exposed at all.

This isn’t to say EMA is wholly irredeemable. As with all creative projects, ’90s EMA happened because its creators were passionate about real issues and wanted others to experience that passion. It happened because these creators had good, if clumsily handled, ideas. The pitfalls of the examples here are many, but there were ways to improve EMA then, and there are ways to make it work for a new generation, too.

Captain Planet and the Planeteers

Animated series often have broader audiences than animated movies, simply because they offer new content over several years rather than a single block of content in a 60- to 90-minute period. Among EMA, the most well-known series is probably Captain Planet and the Planeteers. The series ran between 1990 and 1996, covering four seasons and a smorgasbord of environmental topics. Created by Ted Turner, Barbara Pyle, Robert Larkin, and Nicholas Boxer, the show was originally part of DIC Enterprises, and underwent a company switch to Hanna-Barbera in 1993. DIC produced the first three seasons, with Hanna-Barbera taking charge of the fourth. Under Hanna-Barbera, the show was somewhat retooled as The New Adventures of Captain Planet, with a new animation style and some replacement voice actors. Although new episodes weren’t produced after 1993, the show continued in syndication until 1996. Viewers can currently stream it on Amazon Prime.

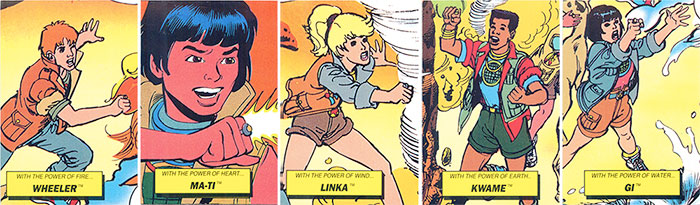

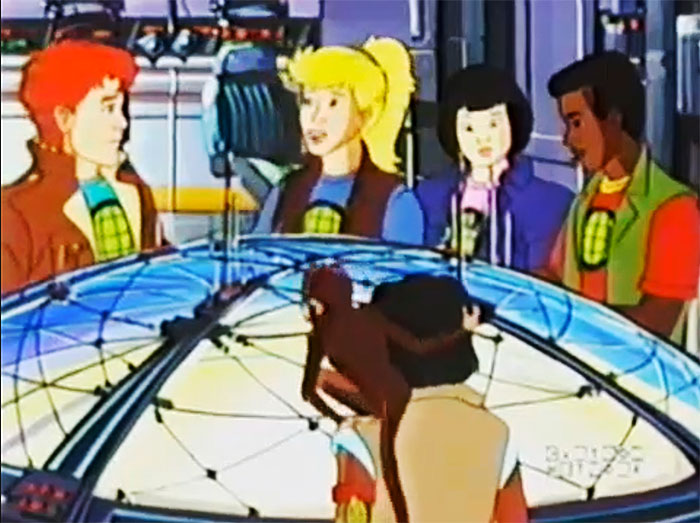

Although the show is best known as Captain Planet, it’s more focused on the five Planeteers. Gaia, the Spirit of the Earth, originally voiced by Whoopi Goldberg, summons these five teens to Hope Island when she “can no longer stand the terrible destruction plaguing our planet” (LeVar Burton, show intro). On Hope Island, a secluded semi-utopia somewhere near the Bahamas, Gaia explains she wants the new Planeteers to save the earth from all manner of pollution. She gifts them each a magic ring imbued with a specific elemental power.

Each Planeteer’s power is connected to his or her specific environmental interests, personality, or culture. Kwame, from Africa, loves planting trees and plants and watching them grow; he receives the power of Earth. North American Wheeler is a tough, hot-headed guy from Brooklyn who receives Fire. Asian Gi is a marine biology student, imbued with the Water power. Linka, from the Soviet Union (later Eastern Europe), has an affinity for birds. She’s connected to Wind, or as we might also think of it, the Air element. Finally, South American Ma-Ti is given the power of Heart. Though not an element, Gaia explains Ma-Ti’s power is the most important of all. It lets Ma-Ti “sense” his fellow Planeteers, read their thoughts and send them positive messages when necessary. In this way, Ma-Ti becomes a super-powered empath, able to rally his friends when the show’s “eco-villains” get the upper hand.

Captain Planet is the manifestation of all five powers combined. In fact, the part of the show most viewers remember best involves one Planeteer, usually Kwame, declaring, “Let our powers combine!” Then the Planeteers raise their rings skyward, call out their elements, and exclaim, “Go, Planet!” Bursting from that spate of positive energy comes Captain Planet, a blue-skinned, green-haired superhero with a red and yellow chest emblem. He is the embodiment of the Planeteers’ elements at their most powerful, able to stop pollution on levels they cannot. Conversely, contact with pollution, such as crude oil, dirty water, or smog, weakens him, sometimes to the point of unconsciousness. The Planeteers usually call Captain Planet in once an episode to help them put away the featured eco-villain for good (until the next adventure). However, one or more of them usually has to use a power to clean or revive the hero so he can complete the mission. Captain Planet always ends the episode reminding the Planeteers and viewers, “The power is yours!” In other words, he’s simply a conduit, a role model to look up to more than imitate. Kids like the Planeteers, and the viewers themselves, have to do the everyday work of saving the Earth.

At face value, Captain Planet and the Planeteers looks like a perfect show and a fun way to facilitate environmental consciousness in kids. The cast is more diverse than many of its cartoon counterparts. Each Planeteer gets more than one episode focused on him or her, so no one reads like a token minority friend. The series is American-produced, but because the Planeteers come from five continents, there’s no sense of ethnocentrism. On the contrary, the cast’s origins give the series opportunities to explore issues that aren’t specific to the United States. Most of the Planeteers are already passionate about the environment, so it doesn’t feel odd that they would be the ones chosen as Earth’s protectors. But Captain Planet loses a lot of altitude when viewers give it a closer look.

Whose Power is This?

The first problem with Captain Planet is the one staring viewers in the face–the title character himself. Again, the idea of creating an ecologically-themed superhero is commendable. Kids and adults alike love superheroes, as proven over and over thanks to franchises like the Marvel universe. And since we are dealing with EMA, what better way to communicate an environmentally positive message than with a protagonist who literally looks like and is named for the planet? But on the other hand, if Captain Planet always saves the day, why are the Planeteers there?

This problem isn’t necessarily about Captain Planet as a person, or being, if you will. The Captain often comes across as the adult the Planeteers turn to when a pollution problem gets out of hand, and considering the target audience, that’s fine. Many cartoons, from all decades, paint adults as useless buffoons or overly strict killjoys, so Captain Planet is somewhat a refreshing change. The sticking point is how Captain Planet relates to the Planeteers, and what he fails to do in relation to what he actually does.

The Captain doesn’t often speak to the Planeteers as responsible young adults. He preaches environmentalism with platitudes and bad puns more than holding real conversations. Once he arrives on the scene, he rarely enlists the Planeteers’ assistance. Instead, he simply takes out the featured eco-villain using superhero antics with environmental twists (vines instead of ropes, storm surges or lightning strikes instead of laser beams). As mentioned, Captain Planet also finds himself on the wrong side of an eco-attack once an episode. These are usually severe; at least once, the Planeteers were led to think their mentor was dead. Since superheroes are often immortal, this punches a hole in a big genre convention. Even if it didn’t, the frequency with which the Captain succumbs to eco-attacks damages his credibility. This becomes more obvious when viewers realize how easy pollution–his Kryptonite–is to get. As the Nostalgia Critic would say, all you have to do is splash oil on him and he’s down for the count.

Perhaps the worst part is that, after each of his appearances, Captain Planet reminds his team and viewers, “The power is yours!” Yet, is it? Viewers of any age would do well to wonder. They just saw the exact opposite play out. The underlying message of a final battle in Captain Planet is that kids or young adults alone can’t make a difference; they need outside influences, especially those with significant if not unlimited power. There’s also the message that adults or “heroes” should get the glamorous tasks or credit involved in making a difference. Young people can only be trusted with the everyday part, which while important, can be seen as grunt work. Not many viewers would favorably compare recycling a piece of paper or planting a seed in a pot with taking down a real villain.

Additionally, young viewers who take this “power” message seriously could be easily and disproportionately discouraged when their efforts seem to bring forth nothing or when adults don’t immediately adopt Captain Planet’s solutions. This writer remembers being bitterly disappointed to hear her parents could not realistically give up their cars for public transit, because her area didn’t have any. Aspiring Planeteers, particularly the youngest audience members, may well find that despite what Captain Planet claims, they don’t have much power as he defines it.

More Answers, More Problems?

A big criticism leveled against Captain Planet and the Planeteers is that sometimes, the solutions presented create more and bigger problems. One YouTube reviewer made the comment that Captain Planet seems to hate space and anything to do with it. One late episode sees him hurling a nuclear missile into space. On the surface, this is a good solution because the missile can’t explode and hurt anyone or anything on Earth, and the young target audience likely won’t think much beyond that. However, the reviewer and their cohorts point out space has a lot of valuable resources. Carelessly hurling a nuclear missile into oblivion means potentially hitting and destroying another planet, galaxy, or constellation. It means polluting space with nuclear fallout, which puts the kibosh on space exploration and potential scientific breakthroughs (as opposed to only space shuttle missions, which ceased in 2011). Yet even if space were a huge, empty vacuum, the underlying message sounds like, “If you don’t like or approve of something, get rid of it. Throw it into space somewhere, sometimes literally, and let it be someone else’s problem.”

Captain Planet’s goals and messages fell apart in other episodes, too. A couple of the most infamous episodes, “Numbers Game” and “Population Bomb,” focused on the problem of overpopulation. Both had Wheeler as their main character, and in both scenarios, he was confronted with the absolute worst consequences of overpopulation, such as starving people or animals (“Population Bomb” had him befriend a colony of sentient mice), and rampant pollution. The basic solution is assumed to be fewer children. Said solution opens the door for discussions of controversial solutions such as one-child policies, abortions, and sterilizations. Taken further, the discussion of overpopulation could and often does lead to questions about who is worthy of life, which puts the elderly, disabled, immuno-compromised, and members of multiple births in jeopardy. When these episodes first aired, many groups vehemently objected to the message, especially political conservatives, for whom a pro-life stance is a platform building block. Members of certain religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, also objected because of doctrines on the sanctity of life, and because Captain Planet’s solution left no room for a benevolent and wise Creator God whose planet could sustain as many people as said God saw fit.

Of course, not every viewer, or their parents, believed in the Judeo-Christian God then, and today’s kids and parents streaming the series may not, either. But that’s hardly a requirement for certain episodes, if not the whole series, to be problematic. “Numbers Game” is probably the biggest offender, because within it, Wheeler comes away feeling like a useless burden to his parents. Whether it was the creators’ intention to send such a negative message, it’s not a stretch to think kids could watch this episode and think having babies, living in an urban area, or using resources in any capacity are bad. It’s also not a stretch to picture kids thinking they, personally, are direct causes of environmental problems.

Other episodes presented both unrealistic issues and unrealistic solutions. In the late episode “Planeteers Under Glass,” our protagonists work with scientist Dr. Derek on her glassed-in environmental simulation. The simulation contains perfected versions of every landscape from tundra to desert, plus idealized, human-created animals, such as hybrids of big cats and eagles, or walruses and fish. Dr. Derek uses the simulation to show the dangers of pollution; a press of a button can show the adverse effects of pollutants over hundreds of years in mere seconds. The conflict occurs when Dr. Blight gets hold of the computer program and speeds up pollution to devastating effects, with the Planeteers trapped inside.

The argument in favor of the episode is, showing pollution in a short amount of time goes a long way toward environmental education. The show is a cartoon and something of a fantasy series; it’s within the genre’s bounds to show idealized environs or fantasy creatures. Once again, the concept itself is not an issue. The issue here is the use of an idealized environment compared to our Earth in a 1:1 relationship. In other words, the implication is that if young viewers do not step up to stop it, the world will look like Dr. Derek’s simulation in a matter of years maximum, and a few years at that. Arguably worse, the episode’s arc is resolved when the Planeteers trap Dr. Blight in an evil, maze-like computer game. Once again, the solution is not real accountability. The solution is not based on what the Planeteers themselves can do. It comes down to Captain Planet’s superpowers and a one-size-fits-all attitude.

Political and Religious Bashing

Many parents and guardians objected, or object, to Captain Planet because of perceived disrespect for certain religions or the privileging of others (as mentioned, ignoring Judeo-Christian or Muslim ethics; characterizing Earth as having a “spirit” in Gaia; arguably privileging pantheistic philosophies). At times though, the series actually did privilege certain political or religious philosophies to others’ exclusion, and wasn’t shy about saying so.

Monotheistic religions weren’t the only ones that ran afoul of Planeteer ethics. In an early episode, “I’ve Lost my Mayan,” Ma-Ti gets trapped in an ancient Mayan civilization and nearly sacrificed so new crops will grow. Captain Planet shows up in time to save Ma-Ti and deliver a lecture on the ills of human sacrifice when compared to environmentally friendly solutions. This time though, he goes too far, telling the Mayans their gods aren’t real and their civilization will die out. The other Planeteers presumably agree 100% with his approach. In other words, while he did not want or deserve to be sacrificed, Ma-Ti spent the climax of “I’ve Lost my Mayan” watching one of his continent’s proudest cultures being bashed. An entire people group were told their gods, whom they depend on and are devoted to, are fake. No matter your belief system, and no matter that Captain Planet probably didn’t have a large Mayan audience, there’s something incredibly jarring about the entire arc.

Throughout the series, a discerning viewer might also sense political bias. As mentioned, Captain Planet’s diverse cast and lean away from ethnocentrism are positive, but there is a negative side to that coin. Specifically, Wheeler, the American in the Planeteers, is usually if not always the one questioning the group’s methods of environmentalism. He is usually the one who needs to learn hard, somewhat graphic lessons about issues like overpopulation. His point of view is the one most often questioned. On more than one occasion, the Eastern European Linka calls him names like “imperialist dog.” Pair all this with Wheeler’s brash personality and his upbringing in a rough urban neighborhood with an abusive dad, and you have a walking stereotype of an “ugly American.” Often, Wheeler is called a “polluter”–the same name applied to eco-villains, who have no conscience and, 90% of the time, pollute Earth because they can.

Viewers on both sides of the American political aisle might well recoil from such implications. Kid viewers who don’t adopt Wheeler as a “soft” version of a villain might feel unnecessary guilt for being like him in any way. Furthermore, if you pair Wheeler’s attitude with Linka’s–environmentally responsible, not imperialist, not from a capitalist country–you could argue the series privileges former Soviet ideology. Parents and guardians might even ask, why was Linka originally written as a Soviet character, rather than a member of another European nation? Failing that, they might perceive Linka, Gi, Kwame, and Ma-Ti as socialist. Since 75% of those characters are non-white, that could also lead to some racist implications about how the show was written.

Clumsily Placed Topics

Finally, Captain Planet and the Planeteers fails as an example of EMA because it often veers away from its own agenda to handle inappropriate topics. These topics are always placed under the “pollution” umbrella, but they never quite feel like they belong. For example, an early episode called “Mind Pollution” deals with drug abuse. While visiting her cousin Boris, Linka discovers Verminous Skumm has hooked him and thousands of other teens on a designer drug, Bliss. Midway through the episode, she becomes addicted, too. The dangerous effects are immediate–sunken, reddened eyes, zombie-like flat affect, slurred voices, and disregard for personal safety, to name only a few. The Planeteers rescue Linka from the “mind pollution” and, thanks to Captain Planet, save the other teens. But Boris dies in the process, right in front of Linka.

It’s not a stretch to call drugs “mind pollution,” but again, the concept is clumsily handled. Drug addiction is reduced to something that can be quickly “cleaned up” and completely cured. This isn’t the case for environmental toxins, and certainly not for real people battling addiction. Additionally, Boris’ almost immediate full-blown addiction and death is another example of speeding up a long process for shock value. Young viewers might be “scared straight,” but they won’t have a realistic picture of how drugs work or why to steer clear of them. Additionally, they may not know how to cope in a real situation where drugs are presented as an option. A drug dealer doesn’t usually look and sound as evil as Verminous Skumm. And while the prescriptions in Mom and Dad’s medicine cabinet can be deadly, they aren’t as intense as Bliss. Usually, they look as innocuous as a pill taken “just one time” to help with focusing on a test or sleeping during a stressful period.

Captain Planet and the gang falls flat again when confronting HIV/AIDS. Once again, this is an understandable topic; the AIDS epidemic was huge news in the early ’90s, and a plethora of misinformation led to stigma and heartache for HIV/AIDS carriers and their loved ones. But yet again, the handling is pretty awful. By its very nature, HIV/AIDS is a thorny topic for kids. As the Nostalgia Critic says, “These kids are just learning how to spell ‘blue,’ don’t tell them about [needles] and unprotected sex!” But, tell them Captain Planet did, in his usual preachy fashion. Teenage Todd Andrews, who finds out he has the virus, is treated as a victim and scapegoat throughout his episode. His entire town shuns him and terrorizes the Andrews family until Captain Planet makes a speech at a basketball game, telling them to “deal with the real.” One two-minute sermon, and the entire town is back on Todd’s side, underlining how easily led these people were. After all, a few scenes ago, they were listening to the evil “gospel” of Verminous Skumm (although no one bothered to question his humanoid rat appearance for some reason).

In addition to the “skummy” moral that “people are stupid,” the AIDS episode doesn’t actually teach the truth about the disease. Todd’s basketball coach practically yells at the crowd, “You can’t get AIDS from casual contact”–and that’s pretty much it. While that’s important, it leaves questions unanswered. Namely, how can Todd cope with his illness? How can family and friends support him so that he leads a fulfilled life? HIV/AIDS is incurable; how should Todd process this, and how can he do so and maintain optimism about his future? Even if Captain Planet had answered these questions, he also didn’t give tips on how to actually “deal with the real” and “get the facts.” What are the facts? How can non-affected people protect themselves? Once again, Captain Planet swoops in, fixes the immediate problem, and leaves a lot of holes that smell rather like the pollution he attempts to eradicate.

Once Upon a Forest

The pitfalls of environmentally-motivated animation in cartoon form are myriad, but cartoons aren’t the only mediums out there. The early ’90s also gave us a spate of EMA films, and it’s a good idea to examine these to see if they handled the topic better. Once Upon a Forest, which debuted in 1993, was probably the most obvious and arguably heavy-handed with its message. The heavy-handedness meant it had issues, but these are different from Captain Planet’s issues and somewhat more balanced with positive elements. Interestingly, sometimes the strengths and weaknesses feed each other.

Empowerment Feeding Incompetence

With its characters, Once Upon a Forest succeeds where Captain Planet failed. The protagonists are based on Furling characters created by novelist Elizabeth Isele and her fellow authors Rae Lambert and Carol H. Grosvenor. The movie introduces us to Abigail the wood mouse, Edgar the mole, Michelle the badger, and Russell the hedgehog. Ages aren’t mentioned, but the Furlings seem to be anywhere between eight and ten. Michelle, the clear youngest, might be about five or six. Like human children, the Furlings interact with their parents and attend school. Their teacher Cornelius is a constant mentoring, stabilizing influence. But unlike Captain Planet, Cornelius does not solve the Furlings’ problems for them. His curriculum, based heavily on natural science, seems designed to teach the Furlings to interact with their home of Dapplewood Forest and become problem-solvers in their own right.

The Furlings, unlike the Planeteers, are on equal footing. They don’t have magical powers, so they can’t create a hierarchy based on who’s stronger than whom, as the Planeteers sometimes did (and as viewers did with them–Ma-Ti still gets nostalgic flak because “heart” is “a lame power”). They’re in their element, not a fantastic or tech-enhanced world, so their conflicts and need to solve them are more immediate and realistic. Since the Furlings are much younger and more inexperienced, it makes more sense for them to make rash decisions sometimes and call on their developing maturity other times. Finally, even though the film itself is American, the characters’ animal status means that once again, their story is not United States-centric. In fact, like Captain Planet, Once Upon a Forest is connected with Hanna-Barbera productions. By 1993, this company had already proven its commitment to the environmental message and diversity within.

However, the Furlings’ strengths feed into their weaknesses on their journey. Michelle is rendered comatose and near death after a truck full of poison gas crashes in Dapplewood Forest. The gas almost instantly kills most of the vegetation and wildlife. The Furlings must strike out on their own to find medicine for Michelle in a strange meadow, while Cornelius, the only surviving adult they’re aware of, stays behind to care for her. The journey is meant to test their intelligence, courage, and self-reliance, which it does almost by default. At the same time, viewers are treated to a lot of bickering, dithering, and immaturity. A couple times, the protagonists seem completely distracted from the mission of obtaining medicine and saving their friend.

Of course, the argument there is, these are children and fairly little children at that. In many ways, the writers, actors, and animators portrayed small children accurately. Viewers of any age can enjoy cheering for the Dapplewood protagonists because they succeed despite external and internal obstacles. Child viewers can “grow with” the protagonists as they learn how to put others first and make far-reaching good choices, just as real children learn to do. Adult viewers can laugh at the Furlings’ more innocuous antics and support their burgeoning sense of responsibility toward fellow animals, their habitat, and the habitats of others.

The execution, though, is clunky. Kid viewers may or may not notice, but adult viewers may feel jerked between moments of childishness and uncharacteristic maturity. The overall feeling, yet again, is that the protagonists are not responsible enough to make a difference. Also, unlike with Captain Planet, the protagonists’ age and cuteness trivializes the environmentalism message. In other words, Once Upon a Forest communicates that an environment, Dapplewood Forest, is important because it belongs to our heroes. However, other environments and habitats may not be as important. Our heroes have not quite reached the age of thinking beyond themselves, and sadly, it shows.

Relatable Characters Feeding Guilt

Flawed as their execution may be, no one can deny the Furlings, Cornelius, and other denizens of Once Upon a Forest are memorable and relatable, especially to kids. You could argue that the use of Furlings, rather than humans like the Planeteers, was genius on the part of the Forest team. Few kids aren’t charmed by cute, furry animals, and most kids in Once Upon a Forest’s target audience are still young enough to anthropomorphize or just coming out of that phase. The overall message then, becomes, “The environment must be protected because the creatures who live there have moms and dads just like you. They learn just like you and might drive their teachers a little crazy. You wouldn’t like it if someone destroyed your home and the people in your world, so respect theirs.” Anthropomorphism aside, that’s a rather solid message. It only gets tripped up when an antagonist is added to the mix.

Without a decent antagonist, there is no story. And in a place like Dapplewood Forest, it would make sense that humans could be that antagonist. Unfortunately, humans have negative histories and bad reputations when it comes to the environment in real life. Any kid or adult who has been exposed to information about forest fires, oil spills, and urban sprawl would recognize why the Dapplewood denizens fear human interaction. Additionally, the writers and producers were somewhat careful to show humans aren’t necessarily evil in their destruction. Cornelius is quick to get Russell and Edgar away from a road, not because humans will kill them, but because cars, driven by humans, are scary and dangerous–as they are for little kids who run into the street. The poisonous gas that nearly kills Michelle is released because the truck carrying it blew a tire, which in turn happened because another human carelessly littered with a glass bottle. We hear the gas truck’s driver exclaim, “I’ve gotta get help,” before running offscreen. These little moments save Once Upon a Forest from painting humans with the same broad, biased brushstrokes as Captain Planet and the Planeteers does.

With that said, Once Upon a Forest maintains the idea humans are careless toward the environment at best and downright evil at worst. The Furlings have it drilled into their heads not only that roads, cars, and pollution are dangerous, but humans are as well. Their main exposure to humans comes from Cornelius’ tragic story of being orphaned back in his home of Willow Brook. We don’t get a graphic description of what happened to his parents, but we do see a menacing, old-fashioned badger trap complete with teeth, and the shadow of a human looming over the family’s den. Later on, the Furlings are reminded of humanity’s evil when they nearly witness the death of a baby marsh wren. The little one’s home has been drained, thanks to the “yellow dragons” (bulldozers). The Furlings are treated to a dramatic funeral, wherein they witness the still-alive baby Bosworth sobbing as he sinks slowly into the muck. His mother sobs as well, nearly hysterical. Bosworth is ultimately saved, thanks to the Furlings’ ingenuity and some well-placed natural resources, which is a plus in the environmental message column. But when Bosworth’s flock leader offers help with the Furlings’ mission, he concentrates on the “yellow dragons” and how humans have turned the marsh into “a cursed ground.”

The implication is, these cute, innocent animals are constantly the target of bullying, uncaring people. Once Upon a Forest does try to redeem itself at the last minute, when Edgar stumbles across a human’s boot (he had lost his glasses and, as a mole, is literally blind without them). The human bends down and nudges Edgar to safety with a, “Here you go, little fella.” But the scene is less than a minute long, the human is largely unseen and unnamed, and most of the interaction leads viewers to think Edgar is in danger, up until the end. Additionally, most of the ensuing scenes still take place in a destroyed Dapplewood, and one shot pans slowly across the destruction. It would be easy for kid viewers to, once again, absorb guilt and take on the entire burden for a huge social issue, at least as much as their developing psyches will allow.

Humans as Inappropriate “Saviors”

Interestingly, the last pitfall Once Upon a Forest encapsulates is the way it paints humans as “saviors” of the Earth. Captain Planet did this too, as will the other movie we will discuss. But Once Upon a Forest is perhaps the most explicit in its “save the Earth” language. Cornelius tells Michelle that “if we all work as hard to save Dapplewood as your friends worked to save you,” maybe one day, the environment will be the idyllic meadow she knew. Couple that with the overall journey of saving Michelle–and saving little Bosworth in the interim–and the viewer gets the impression that the Earth is helpless. Adult animals might have more agency, but they, too have little choice but to run (or fly, or swim) scared from interference in their bucolic world. Humans, then, become a strange combination of devil and angel, the Earth’s version of Satan and the only one who can keep it safe.

To say this is confusing is an understatement. For an adult, it’s odd, but adults also have a better grasp on environmentalism’s complexities. Many adults consider themselves “conservationists” instead of “environmentalists,” citing the Earth’s ability to replenish itself and humans’ ability to be responsible with resources. But for the target audience of most EMA, the solution to environmentalism’s conundrum is less clear. Does “saving the Earth” mean never picking a flower, using transit or electricity, or eating meat? Does it mean we can use resources, and if so, which ones and how much? When will we know the Earth is “saved,” and what if we can’t save it? Indeed, today’s kids are more worried than ever about climate change, resource depletion, pollution, and similar issues. But should they feel guilty or take on the mantle of Earth’s new heroes? Parents who show their children EMA in the name of bonding and nostalgia will find the answer is unclear. And while it’s okay for a parent to answer children’s questions with, “I don’t know,” environmental questions might prove too high-stakes.

FernGully: The Last Rainforest

Hitting box offices in 1992, FernGully: The Last Rainforest is actually the earliest example of environmentally-motivated animation in our discussion. However, we’ve left it for last because it is simultaneously the least and most problematic of our examples. It improves on several elements the other two bungled, from the role of humans to the agency of animals and other creatures. The Australian-American production also brings a non-American environment to life in minute detail. Simultaneously, it maintains the issue mishandling of our other two examples, while worsening that mishandling on various levels.

Character Agency Drawn from Environmentalist “Religion”

One of the best things FernGully gets right is giving its characters more agency than the characters in our last two examples. Crysta, Pips, Batty, Zak, and the other FernGully denizens are not teenagers letting a superhero handle their problems, nor are they cute but hapless animals. They are, instead, independent and interdependent creatures who know their environment inside out. They work to protect FernGully not only because their lives will be at risk otherwise, but because they truly love and understand this “last rainforest.” They don’t consider FernGully a helpless or dying habitat to be salvaged. It is a life-sustaining home that can benefit anyone, even those who seek its destruction and therefore, deserves protection even if it can eventually replenish itself.

To that end, viewers get to see main character Crysta, a rainforest fairy, and her friends and mentor protect FernGully in ways that play to their strengths. Crysta, for instance, spends a lot of time nurturing and protecting trees because they’re special to her. Fairy leader Magi Lune may have particular floral powers, considering flowers grow from her feet wherever she flies or lands. Pips and some other fairies are shown to live near a cadre of mushrooms, which may indicate they have responsibilities toward particular plants and fungi depending on their interests or hobbies. The fairies use their powers to make FernGully stronger and more fertile, without seeking help from outside forces such as a Captain Planet-esque hero. Magi Lune is a wise old mentor like Dapplewood Forest’s Cornelius, but she doesn’t send proteges like Crysta on missions with little preparation, nor does she pressure her mentees with rhetoric that communicates FernGully depends on them alone. Rather, Magi works with her mentees, teaching them “the secrets of the forest” as they grow and progress. By the time we meet protagonist Crysta, she’s already been under Magi’s tutelage for a while and learned a great deal, but she still has some maturing to do, as seen when she slips out of FernGully on adventures, sanctioned or unsanctioned.

It is because of Crysta’s adventurous spirit that character agency breaks down, though. She unwittingly discovers human Zak Young and a logging camp, the supervisor of which is tasked with razing FernGully. This mission is complicated when Zak accidentally releases Hexxus, a toxic embodiment of pollution and death (appropriately voiced by the hammy yet spine-tingling Tim Curry). In trying to make Zak see the seriousness of what he’s done and is doing, Crysta accidentally shrinks him to fairy size. This would all be fine, however, if her “lesson” didn’t get increasingly heavy-handed from there.

Zak is a reasonably intelligent human being, so he has little trouble understanding why Hexxus is bad news. However, he struggles with why cutting down trees, evicting fairies from their homes, or other anti-environmental actions are problematic. At first, he thinks since the fairies are magic, they can automatically fix FernGully whenever they want–and the movie itself seems to support this theory. But as Crysta explains, the damage Hexxus and humans have done in the past is too big for fairy magic alone to fix. More importantly, humans should not rely on fairies to clean up their messes. Instead, humans should learn to understand how they impact the environment. Specifically, Chrysta says, humans cause the forest to feel pain when they pollute it or cut down its trees, and they cause the fairies untold grief, especially older ones like Magi Lune. And Magi Lune cannot afford such grief, because she is already dying. Her only hope is to pass her wisdom on to Chrysta, who will then take over stewardship of FernGully someday soon–if there’s one left.

As with the other environmental messages we’ve covered, on its face, there is nothing wrong with Chrysta’s message. There definitely isn’t anything wrong with her passion for FernGully, either. But Chrysta’s passion is so insistent it often becomes borderline hysterical. Her beliefs that the forest feels pain on a human level, and that fairies are responsible for the spirit of the forest, also read a lot like theology. FernGully: The Last Rainforest, then, provides the most blatant example of “environmentalist religion” we have seen in this discussion. Whether this is offensive depends entirely on who you ask. Yet such an attitude muddles the environmentalist message yet again; is environmentalism a scientific issue or a religious, moral issue? Is it both, and if yes, is environmental morality on a par with traditional religious morality (Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, etc.)? As noted, the muddling also damages character agency. That is, if Magi Lune and other forest spirits are the main reason humans should take care of the environment, what place do Chrysta and other fairy characters have? If fairies can use the forest’s pain to “motivate” humans, why doesn’t the forest show its pain or needs directly? If families and especially children are supposed to enjoy the film and absorb environmental messages, these probably aren’t questions they should ask.

Mixed Messages Regarding Villains

Additionally, FernGully succeeds in crafting appropriate villains–mostly. The first and most memorable villain is Hexxus. As noted, he is a huge ham, such that adults might laugh at some of his lines or antics. But Hexxus’ amorphous, dark form of toxicity personified gets the anti-pollution message across without vilifying actual humans. Better, since Hexxus is non-human, he doesn’t have to deal with the complexities of environmentalism. His pollution doesn’t have potentially positive side effects, such as providing jobs or livelihoods for people who need them. He doesn’t explore the moral dilemmas some of Captain Planet’s solutions create. And since he doesn’t kill any humans or cute animals, Hexxus can be scary without becoming a direct threat to the audience or the planet they know. Unlike other villains, Hexxus shows viewers pollution is scary and bad, but people and their environments are not necessarily so for “letting” pollution happen. A non-human and non-animal entity, Hexxus explores the idea that pollution happens because no world is perfect, and other entities can’t make it so. The best they can do is stop pollution when it happens, as Chrysta and her crew do with Hexxus. In fact, Hexxus is the only casualty of the movie.

The villains of FernGully do suffer from a few mixed messages. At times, the idyllic environment acts as a villain itself. One of the better-remembered scenes, and one nostalgic viewers recall as the scariest, happens between Zak and a hungry rainforest lizard. The lizard hungrily eyes Zak and sings, “If I’m gonna eat somebody/it might as well be you,” in a jarringly deep voice. He continues daydreaming in song about how good Zak will taste. Zak does escape, but the lizard’s desire to feed, coupled with his disturbing voice and scary design, might make him seem more like a Hexxus minion than a friendly rainforest resident. Couple this with Zak being shrunk down via magic, and the FernGulley environment starts to look indiscriminately hostile. For an animated family movie whose environment is supposed to be fantasized, fun, and idyllic, the messages feel a bit too muddled.

Finally, although FernGully mostly ducks the idea that humans are combined villains and saviors, it does trip over the trap a bit. Namely, Zak is brought into FernGully primarily to learn how harmful pollution is–not, for example, how beautiful and beneficial the environment is and why it deserves preservation. He’s basically “captured” and forced to undergo fairy magic, which hurts our protagonists’ credibility when they say humans can be helpful or that they wish to cooperate with them. Zak and his fellow humans do stop the Leveler and take down Hexxus–because one chosen human, apparently more special than all the others, has been preached at for 60-90 minutes. Again, the message lacks subtlety or the opportunity for many people who aren’t “chosen ones” to make positive impacts.

Overly Adult Implications in Idealized Packaging

The final place FernGully gets clumsy is its attempt to draw older viewers into the plot. Like Captain Planet, FernGully deals with some topics inappropriate for young kids. These topics aren’t as “in your face” as Captain Planet’s iterations, and because FernGully is a movie, they are less frequent. Some of them are handled with humor, meaning adult implications may go over the target audience’s heads. But the fact that the implications exist and are talked about on a child’s level damage the overall goal of the film.

The first and most frequent example is embodied in Batty Koda. Batty, voiced by the late Robin Williams, is a naturally sanguine, funny character who does provide good comic relief. Calling his history dark, though, would be a massive understatement. Before the refuge of FernGully, Batty underwent myriad laboratory experiments. He sings about how humans stuck red and green wires right into his flesh, dissected parts of him while he was still alive, and committed other unspeakable horrors. At one point, Batty also pleads for medication in a stereotypical unhinged manner. He hints the doctor running his former laboratory home was an intensely unstable person. But most of this is done through song or the veil of his “kooky” personality. As noted, the “veiling” may shield younger kids from the implications of animal capture and experimentation. However, the target audience is still meant to grasp Batty has experienced untold trauma, as do animals in real life. Thus, when his kookiness or mental instability isn’t played for laughs, it can become disturbing on an arguably inappropriate level. The message becomes, “If pollution can’t kill, it will make innocent things and people unfamiliar and scary–and you will have to live with that.”

Hexxus is another example, and perhaps the best. Again, he is a much better villain than the other EMA baddies we’ve encountered. Keep in mind though, Hexxus does not just spread pollution. He is the embodiment of not only pollution, but all the negative forces in FernGully. He’s called the Spirit of Destruction, and can only be stopped if he is sealed in an impenetrable vessel–which proves not to be so airtight throughout the film. Additionally, Hexxus isn’t content to use the pollution humans create through Levelers, poison gas, or the like. He’s not content to build machines or other pollution sources like the eco-villains in Captain Planet did. Rather, Hexxus literally feeds on pollution. Smoke and other toxins keep him alive and strong, to the point that he eventually becomes an overpowering, screen-encompassing force. By this time, all his hammy singing and sarcastic humor is gone, too. Hexxus becomes a nebulous Thing best compared to a rainforest demon, if not a traditional demonic representation.

If Hexxus’ evil powers were downplayed a bit, or if he were in a more serious type of film aimed at older audiences, this might be fine. Nostalgic viewers such as this writer can appreciate him as one of the great animated villains, and he might not prove “too scary” for some kids, depending on what they’ve already encountered. What’s worth concern here is, Hexxus isn’t just a typical “kiddie” version of chaotic evil. He’s a force who, once unleashed, can only be stopped through ultimate sacrifices, which could hurt the environment more than help it. He doesn’t simply hurt or kill the environment–he eats and obliterates it. At times, Hexxus can be read as making pollution as unstoppable and all-consuming as he is, for the environment and humans alike. Coupled with Batty, the “neutralizing” of Zak, and the worldview of the fairies, Hexxus might be read as a villain who wants to consume and pollute anything and everything. The dichotomy feels inappropriate for the setting, and the environmental message feels too broad and unfocused.

Is There “Good” Environmentally Motivated Animation?

To conclude EMA is a worthless genre that harms kids would be erroneous and unfair to the former viewers who enjoyed these series and films, as well as the current kids and families who will likely enjoy them. The three examples we’ve discussed needed a defter and more circumspect hand, but possessed plenty of merit. The key with past, present and future EMA lies in balancing its messages, sticking to one or two topic facets, and presenting cooperation and change as possible.

There are examples of EMA around today that succeed here, or at least do much better than their predecessors. Most of them are geared toward an older child and adult audience, and facilitate more nuanced discussions than early ’90s examples. The Secret of NIMH, for instance, puts its woodland protagonists through some potentially horrifying trials and references medical experiments done on mice. But because the animals exhibit constant agency and face threats from both humans and fellow animals, the environmental message is more nuanced and subtle. Humans are rightly castigated for experimenting on the mice, but some of those mice possess human-level intelligence. In other words, they are somewhat on a par with humans, and in a better position to explain how their universe should work as part of the wider human and animal world. Similarly, Watership Down is notably graphic in its depiction of animal survival, injury, and death, but pollution and humans are barely part of the equation. Instead, Watership Down focuses on how the environment itself can be both a refuge and a danger–again, through giving its characters agency and time to grow, rather than preach or plead for their lives.

Whatever environmentally-themed conversations families choose to have, they will find good and bad examples of how to conduct them in EMA. How successful those conversations are will depend not only on the personalities of the children watching, but how EMA is interpreted and discussed. Thus, the more questions and nuances in a conversation, and the fewer “easy” answers, the better.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Each of these works were released years before I was born so I don’t have any rose-coloured nostalgia linked to them. But I would have assumed that environmentally motivated entertainment for children, on the whole, would be a positive thing. I mean, a fun show that teaches children to recycle sounds great, right?

For that reason it was insightful and entertaining to read your arguments on why these shows are not necessarily exemplars of environmental justice. Your argument about Captain Planet being a saviour that might leave viewers disillusioned will likely stick with me, because you’re absolutely right. If the power were truly all ‘ours,’ why would we need a superhero?

Great work here, I always enjoy reading your articles! 🙂

I thought Captain Planet was cool. I thought it was great that the spirit of the earth gave power to kids to fight pollution. Made me choose a career in sustainable development.

Any other type of superhero would have waved a magic wand and fixed environmental issues for you, without any effort on your part, which just isn’t how reality.

Yeah, “the power is yours” did it what it was meant to: made nine-year-old me feel good about separating the recycling.

The worst part of Captain Planet was the intro music, it was unbelievably weak. How did it even get through production? It screamed “this is going to be more rubbish than the rubbish it rubbishes” (even if it wasn’t). Give it a shot on Youtube I dare you; then listen to the intros for Thundercats, He-Man, Battle of the Planets, or Ulysses 31.

All of them still hold up to this day.

Hahaha you are so right!

Captain Plainet was one of the hokiest cartoons on television but it did have a positive message *sings theme tune in head*

I think Captain Planet and the Planeteers it did help spread an environmental message to kids in an accessible way.

The villains were a bit of a weakness, as they seemed for the most part to want to ruin the planet out of sheer, perverse, nebulous evil, rather than being irresponsible or motivated by greed. They just tore down forests or dumped toxic sludge in rivers for its own sake, rather than having a comprehensible motive. I don’t think that really helped kids understand the reasons our planet is under such dire threat.

But otherwise- they deserve at least a little credit for trying to make a positive difference.

Exactly my point. I don’t have a problem with the intention, but as I said, the execution left much to be desired. I’m aware that I may be biased; I came from a family that, while respectful of the environment, was diametrically opposed to Captain Planet *as it was presented.* But from just a writer/creative person’s perspective, I still see a lot of flaws.

The producers have said that the eco-villains were intentionally exaggerated because they didn’t want children to believe that real-world people who work in industry are cartoon villains.

Captain Planet was (for the time) uncomfortably frank for a kids’ show about certain other hot-button issues- e.g. HIV and gang violence. It’s therefore doubly disappointing their moral courage didn’t extend as far as confronting consumerism.

Once Upon a Forest scared me as a kid. I probably only watched it a couple of time but message stuck with me for life.

Me too. It is not a movie I enjoyed watching as a kid just because of its dark tone, but I get why it was done this way.

I really liked FernGully film and all of its performances. The style is so 90s with all the musical performances and Robin Williams’ bat rap but that’s what makes it great!

I love this movie I grew up on it I know it’s old but still good.

Captain Planet was one of those shows that as I kid I initially enjoyed, but gradually got more an more fed up with it. As with a lot of 80s/90s cartoons, the good guys were all insufferably smug good-two-shoes (except for the American boy, who was Always Wrong and had to Learn An Imortant Lesson – which often contradicted the one he was taught in an earlier episode).

And unlike, say, He-Man, it didn’t even have decent villains to make up for the boring heroes.

Right. My little brother and I watched the show for a while, but then my parents sat down to watch it with us. They decided Captain Planet and his “team” were no longer welcome in our house, after explaining why (they found it insulting to Christians and conservationists, my dad in particular hated the “liberal” agenda, etc). If I had kids of my own, well… I don’t know. I still find the show careless and irresponsible in a lot of ways, as you could probably tell. And honestly, I think if I had an 8-10-year-old right now, they might take one look and be really bored. Like, “Mom, are you kidding me?” But then I think we might have something good to talk about. Maybe we’d have an “unplugged” day or help out at a farmer’s market.

Used to watch it occasionally as a kid but definitely found Flash Gordon and Defenders of the Earth better.

I thought that this series was great, and de rigeur watching for our children. On balance the overt messages were more important than the underlying silliness.

What I mean by underlying silliness is that all the industry featured was bad, polluting, and needed to be stopped.

They should just bring back the cartoon, it was rather splendid. They could probably make a version of The Dreamstone which would really appeal to families.

Never saw the cartoon, but the Amiga game was pretty lame.

Ahhhhh… Captain Platnet. I think the episode where he pushed an acid rain cloud over a forest to save a city, and where he tried to talk to children about AIDS (while confusing it with the HIV virus) sealed the deal for me when I was 9. That’s when I realised some cartoons (and therefore adults) really didn’t know what they were doing!!

Exactly. Decades later, adults still struggle to entertain and connect with kids on a meaningful level–and I say that as an adult who was once a teacher and tried her hardest but probably didn’t know what she was doing, either. My problem was, I came from an advanced student, school-loving background and was probably overly passionate about the content. Captain Planet’s writers were probably overly passionate too, with a good dose of overloading thrown in. That is, they tried to cover so much stuff, and so many issues and POVs, that the whole thing just got hokey.

With Captain Planet, what I can never forget is the horribly cringeworthy method employed for summoning the titular superhero.

The Planteers would thrust their rings out in front of them (and sadly that isn’t a euphemism), shouting their respective “power”: Fire! Water! Earth! Wind! and… Heart?! Really? Heart?! I wonder how that kid felt when they were doling out the rings and he got lumbered with that turkey?

Anyway, even as a child this segment made my teeth itch, and even thinking about it now it makes me shudder. A truly awful low budget animation. Perhaps not the worst, but certainly not a show I’m in any hurry to rewatch.

Can I borrow the phrase “made my teeth itch?” And you’re right, a lot of the show was not only cringey, for reasons I outlined, but just…weird. As for Heart, I personally wouldn’t have minded had I been told, “This basically means you’re a superpowered mind-reading empath.” But the way Gaia handled it, or didn’t handle it, means that yes, Ma-Ti got landed with a bad deal. He seems to be the butt of the joke or the one dealing with the worst fallout in several episodes, such as the infamous Mayan one.

He could control animals with his “Heart” ring, the potential was endless. The problem was that he was dim-witted and rarely if ever saw the potential.

Nowhere near as bad as the deal Donatello got in Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles. Leonardo: razor sharp sword. Donatello: lethal sai daggers. Michelangelo: deadly, borderline-illegal nunchaku. Donatello: a stick.

I wasn’t a TMNT fan, but yes, it does sound like Donatello got the worst choice of weapons. I can appreciate the characters being named after Renaissance artists, though.

just imagine someone making a hollywood blockbuster movie based on that. it would never work.

This used to be on straight after Captain N (for Nintendo) on Saturday mornings, and I’ll happily take that over any of today’s “Oh look Henry, here’s a stick – let’s go and play with it and learn about diversity at the same time!” bollocks.

The Secret of NIMH is one of the scariest films I’ve ever seen. Wouldn’t show it to my kids.

I liked Once Upon a Forest, though. The birds’ song was fun.

I remember getting lost as far as the plot of The Secret of NIMH, but as an adult, I see more artistic value in it. As a kid, I got creeped out by the “funeral” half of the birds’ song, but I also had this thing about funerals, graves, etc. Not quite necrophobia, but whatever the mild version is. That said though, yeah, the second half is one of the better parts of the film. I can’t decide if I like the African-American gospel feel to that scene though, or if it’s insulting.

Great informative list of animation that have a green theme.

Wall E actually hits you hard on what we are doing to the environment, I never thought animation could achieve this! There was a movie – Passengers, somewhere on similar lines but it didn’t leave as big an impact. From your list, I am yet to watch Once Upon a Forest, looking forward to it now!

I considered using WALL-E here, but Pixar is a different type of animation. I also wanted to stick close to the ’80s and ’90s, since while environmentalism is big now too, the conversation was somewhat different then. I like to write from a nostalgic perspective when possible.

Yes, Pixar does it! Passengers (2016) right? I think it’s more of a romance movie.

A great round up. My teenage daughter has seen all of these and she is very environmentally aware. She was particularly taken with FernGully. The message is everywhere now and that is good. Also, we take as much action as we can as a family to keep our environmental impact low.

A superhero in charge of protecting the planet, but whose only weakness is pollution? He was about as useful as Superman on kryptonite clean-up duty.

Exactly. I don’t know how they could’ve improved that, though. Maybe if his weakness were a very specific *type* of pollution that was difficult to obtain or produce, like a futuristic chemical? Oh, wait, that’s Kryptonite. Heck, maybe he could just have a regular allergy that got out of control sometimes.

I loved Captain Planet as a kid and I’ve no doubt that it helps contributed to my way of thinking now. However i only found out recently about all the high profile actors who voiced the characters!

Still have my action figure somewhere I think! (also great to read they were made of recycling/reclaimed plastic!)

Me and my friends loved this show when we were at school! We used to play Captain Planet in the playground.

Captain Planet got me and many others interested in conservation and other similar interests, so I think it did it’s job – what shows from your childhood have dated so wonderfully in comparison??

Yes exactly! It was about creating awareness among kids – educational and useful entertainment for kids, which not many other cartoons attempted to do.

Besides he was cool and I have a t-shirt of him.

I may not may not still have the action figures… i might have been strong enough to ditch them in the last clear out, not sure. I used to wear the ring you got with the action figure for each of the elements when i was at school.

I remember reading the Wikipedia entry for Captain Planet about a decade ago. I burst out with laughter reading about his superpowers. It said something along the lines of “His powers would adapt to fit any given situation or problem he came up against.” My thought at the time was that it pretty much made him the most powerful superhero! Hilarious! The article has changed since then though.

I loved Captain Planet, he was a real hero, overall educational and he tackled real life problems. He contributed in making me and many kids of my generation realize the importance of recycling, cutting down waste, keeping our environment clean, the major role our ozone layer plays, and what each of us could do to help, etc.

These are fundamental teachings that sadly still need to be spread. Go, Planet!

Hated hated this show as a kid. If you want to see something that is god-awful go and watch the episode set in Ireland. I dare you. It was such sanctimonious rubbish that it would make you take up dumping litter etc. in order to say —- YOU Captain Planet!

I can understand, especially as a Hibernophile (lover of Irish culture). Unfortunately, it’s not currently possible for me to get high-quality episodes on free services, and I’m not (yet) willing to pay for it on Prime (it’s a premium subscription). And yes, as I discussed in the article, there are plenty of other less-than-stellar episodes.

Once Upon a Forest has a very quick but one of the best twists on how Man is portrayed. I won’t spoil it, but it was a delight to watch.

Yes, and I do appreciate the twist. I think it could’ve been delved into more deeply, but matter of opinion and etc.

This movie tries to ram an eco message down your throat but it’s still super sweet and innocent in a way.

It’s still quite a nice children’s movie but I don’t think I would recommend it for children.

I remember watching FernGully and the sequel as a kid and I have to say, this brings back good memories.

Once Upon a Forest is so much an eco-toon that in the end we would expect for the lead character to turn to the camera, take his hat off and plead for our help to save the environment. 🙂

Seriously. I mean, points for effort, but can we be a little more subtle?

I cried on several occasions throughout the journey that the little fur-lings made.

I seem to recall that the Planeteers each had their own special power. Four of them had the power of the elements, but one unlucky one got lumbered with the power of Heart, whatever that means.

Even as a kid I remember feeling sorry for him. I mean, Earth, Wind, Water and Fire all seemed like a reasonable basis for a superpower, but Heart? What was he supposed to do? Love his enemies to death? Give them an STI?

LOL, I know, right? I guess the idea was it takes “heart” to help the environment, or else it’s just a bunch of elements that are great but have nothing to do with humans. They kind of did a riff on this when the Planeteers fought a villainous army with powers like Smog, Toxins, and…Hate. But again, really bad execution. Poor Ma-Ti.

I always spent the episode yelling at that Planeteers to stop their (obviously futile) attempt to fight that villains themselves and jump to the part where they summoned the Captain.

Though if they did summon him early you knew he was going to get himself whupped.

The climate has been changing back and forth for eons. But yes, due to the greed, lack of sustainable focus, dark weather manipulation, chem trails, fossil fuel and other mining, dark governments and those that control it, on and on, the planet is being destroyed. Thanks you for focusing on this topic.

The thing I remember best about the Captain Planet cartoon was the amazing voice cast they assembled for it. LeVar Burton, Whoopi Goldberg, Tim Curry, Ed Asner, Meg Ryan, Sting, and Malcolm McDowell all did voice work for the show.

Yes, that was an amazing voice cast, and they clearly worked hard on it. It makes me kind of regret my own opinion, if that makes sense?

There is that one gem of an episode where Captain Planet manages to ‘solve’ Apartheid, the Troubles, and Palestine all in the same afternoon, by doing a thing, or something.

Yeah, some of the episodes, including that one, were extremely weird, in that it was a real stretch to call the evil stuff happening in them “pollution.” You could make a slim argument that those were focused on the “heart” aspect of saving the planet, so to speak. But I don’t know if that “works.”

I love FernGully. My parents used to watch this movie with me, now I watch it with my children. Wonderful movie!

I vaguely remember Captain Planet from being very, very young.

To add to the article regarding Captain Planet’s overpopulation episodes, given the implicit message (less people), combining with Wheeler felling as of a burden to his parents, it’s not a big stretch to think that the show, unwittingly or otherwise, just told their main audience (children) that they are a burden and should feel bad for existing. Regardless of the intent, it’s a negative, even rather dark message.

I was fortunate enough to grow up watching both “FernGully” and “Once Upon a Forest” as a child, and watch them over and over I did. My favorite aspect of both these movies is their music. “FernGully” has a short song featuring the dulcet voice of children’s singer Raffi, along with Hexxus’ villain song by Tim Curry and even an ending credits piece by Elton John. This is, of course, excluding Robin Williams’ song, it really is not good. And “Once Upon a Forest” is graced with a song by Michael Crawford, none other than the Phantom of the Opera himself, called “Please Wake Up.” It’s a tender song made all the more tender by Crawford’s sonorous voice. And these are not to mention the orchestral soundtracks by Alan Silvestri and James Horner, respectively. As is often the case for animated movies, a good soundtrack can help viewers forgive story elements or shoddy animation that otherwise would work against the movie’s quality. I’d say it’s worth watching both these movies for the music alone.

I honestly have not watched any of the examples that you have mentioned here but as someone in the thread already pointed out, “environmentally-motivated animation” sounds like a positive message. I will follow this article up with some personal reading but all in all, I learnt something new today.

I’m super late to this post, but it was a lovely read, so thank you for the work you’ve done here. I think there’s an important nuance you begin to pull at in the end, and that so many of our stories “about” the environment miss: the difference between having characters act on the environment or to “save” the environment and acknowledging that we are all characters in the environment, and that the environment itself is made up of characters who deserve our respect. When well-written, animal protagonists help portray this message, because they don’t just tell us that “humans” need to “save” something abstract called “the environment,” but they make us love and care about those with whom we share our more-than-human environment.

Confused about your usage of the word racist and your prescription of 75% of the Planeteers being socialists. Remember Ted Turner was a Billionaire and Linka was rarely presented as right in being so “haughty” towards Wheeler.

That said you do bring up some good points about how poor environmentalism and other social issues are and were handled in animations of the 90s.

It’s always fascinating to see the various strong and weak points of these shows, especially with an attention to detail like how you wrote! It would be interesting to see future attempts to run an environmentally-motivated animation on film or TV. After all, technological advances and constant research have improved our understanding of the climate, the impact of pollution, and the consequences of misusing earth’s resources.

Perhaps as a follow-up to this post, you could maybe take a look at some eastern films that tackle similar issues, such as some Studio Ghibli films. Princess Mononoke seems ripe for this kind of analysis, but other films like Nausicaa of The Valley of The Wind could be fun to dissect as well!.