Annie Hall, Star Wars, and The Battle Between Art and Commerce

1977: A Tale of Two Movies

The 1970s is still widely considered to be a “golden age” of sorts for American cinema. Unlike the Hollywood classics of the late 1930s and early ’40s, these films were bold, subversive, and decidedly modern, even post-modern at times. Prior to the 1970s, producers like Cecil B. DeMille and David O. Selznick were often more prominent than the lowly filmmakers. Yet, it was the directors Martin Scorsese, Hal Ashby, Robert Altman, and Francis Ford Coppola who reigned, churning out epochal masterpieces such as Mean Streets, Harold and Maude, The Conversation, and Nashville. In 1975, however, the realistic, thoughtful films which defined the first half of the decade slowly started to morph into childlike fables with astounding special effects. This was primarily due to the emergence of Steven Spielberg, whose 1975 Jaws became the first film to gross $100 Million in the United States. When compared to the aforementioned “New Hollywood” classics, however, Jaws was simplistic, lightweight, and manipulative.

1977 proved to be a pivotal crossroads for American film; a year that predicted the cinematic trends of the subsequent decades. This is largely through two films: Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, a Best Picture winner that accidentally gave birth to dozens of talky indie dramedies, and George Lucas’ Star Wars, the cinematic event that killed the ’70s renaissance and allowed egomaniacal hacks like Michael Bay and James Cameron to flourish. This article delves into these two iconic works of cinema, analyzing the lasting impact of both Lucas’ and Allen’s achievements.

Star Wars: Hundreds of Years of Clichés and Archetypes, Brilliant Props and Effects

It is difficult to imagine now, in the age of Avatar, Star Trek: Into Darkness, and Guardians of The Galaxy, but in the 1970s, science fiction was essentially a dead genre. At the tail end of the 1960s, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey was a breakthrough, but its science fiction was philosophical and cerebral. The film was far more admired by academics and the drug crowd than the average moviegoer. Between 1968 (2001‘s release) and 1977 (when Star Wars premiered), the science fiction genre was nearly non-existent in the U.S. The few that were released were speculative and political; the idea of a swashbuckling space opera, a la Flash Gordon, was laughable and inconceivable. Akin to Coppola and The Godfather, Hollywood expected George Lucas to fail spectacularly with Star Wars. Also like The Godfather, the film completely subverted these expectations, and became an unprecedented hit.

While The Godfather was a complex and intricate exploration of American values, Star Wars is a gleeful return to Lucas’ youth, and an appeal to the inner child of moviegoers everywhere. Many of the “New Hollywood” directors were heavily influenced by the groundbreaking cinema of foreign filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard, Federico Fellini, Satyajit Ray, and Akira Kurosawa. While Lucas himself admitted to borrowing much of Star Wars’ story from Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress, the true DNA of this blockbuster is found in the serials and radio shows of the Great Depression era. The film is a derivative throwback through and through, mining everything from Arthurian legend to Saturday morning cartoons. Despite these recycled elements, Lucas’ groundbreaking special effects conveyed a sense of innovation and futurism.

In 2001, Kubrick deliberately let stunning cinematography and a realistic visualization of outer space overshadow the human characters; after all, his main point was to emphasize how technology has overtaken humanity. In contrast, Star Wars is perhaps the first movie where the special effects, not the actors, truly take center stage, for the sheer wonder and awe of the high-tech visuals. Despite the efforts of future mega-star Harrison Ford and acclaimed British actors Alec Guinness and Peter Cushing, the characters are so thin and archetypal, they barely appear human. Moviegoers often wonder why Mark Hamill and Carrie Fisher were never able to embody characters as memorable as Luke or Princess Leia, but there is a simple reason; these roles could never prepare an actor to convincingly portray a complex human being. These characters may be iconic, but do any of the film’s performers make an impression akin to Gene Hackman or Ellen Burstyn, Jack Nicholson or Sissy Spacek? The answer is quite obvious.

Star Wars also marked the start of a fatal trend: movie as brand name. The hawking of merchandise during the film’s initial release is legendary, and the toy-store tie-ins have only become more blatant in Hollywood in the following decades. Several years prior, counterculture audiences were blown away by the rebellious, lifelike Five Easy Pieces and The Last Detail. Star Wars unleashed a seismic shift which saw audiences clamoring for escapism. A decade after Chinatown and Taxi Driver impressed viewers with relentless darkness and unvarnished realism, all the average moviegoer cared about were one-liner spouting cyborgs (The Terminator) and children with aliens as pets (E.T.) This trend continues, with Marvel comics dominating the multiplex, and The Lord of The Rings/Hobbit series acting as the indulgent, money-hungry Star Wars of the 21st Century.

Lucas could not have predicted the success of Star Wars, and therefore his reasons for making the film were not financial. Instead, his intention was to return to a simpler time before the unruly 1960s and 70s, in much the same fashion as his previous hit, 1973’s hyper-nostalgic American Graffiti. In a decade that saw Watergate and an endless war finally come to a close, it is easy to see why audiences began to tire of films about homicidal cabbies and government corruption. However, in the 1980s, culture was greedy, gaudy, and glitzy, and the summer blockbusters followed suit. In a reality that seemed more and more like Hollywood, cinema simply reflected society, rather than offering a sorely needed escape.

In the masterful 2000 Taiwanese film Yi Yi, a youthful cinephile enthuses about cinema’s ability to reflect life, noting, “Man has lived three lifetimes since cinema was invented.” This maxim was rarely affirmed more completely than in the works of Altman, Coppola, Scorsese, and Ashby. Lucas and Spielberg’s breakthroughs, conversely, turned away from the messy complexities of the real world, and attuned instead to naïve dreams and Technicolor visions. This refusal to accept all that life has to offer speaks to the pervasiveness of summer blockbusters and a culture of sparkly fantasy and empty flash.

Annie Hall: The Accidental Father of Indie Romance

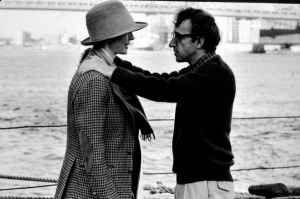

Before 1977, the cinema of former stand-up comic Woody Allen appeared more indebted to Peter Sellers or Jerry Lewis than Altman or Coppola. To be certain, Allen’s neurotic nebbish persona was far more intellectual (and Jewish) than his comedic predecessors. Yet, his hilarious but rather superficial laugh-fests like Bananas and Sleeper seemed out of step with the artistry of “New Hollywood,” and none of his early comedies had the cultural impact of the Mel Brooks classics Young Frankenstein and Blazing Saddles. With 1977’s Annie Hall, Allen’s cinema took a quantum leap in ambition and complexity, leading the way to decades of future triumphs, from Manhattan and Hannah and Her Sisters to Midnight in Paris and Blue Jasmine.

Yet again, Allen may “play” comedian Alvy Singer, but in reality he is just playing himself; or at least a carefully crafted public persona. Unlike his earlier films, however, Allen’s pathos and aching vulnerability seep through the surface of highbrow frantic humor. Diane Keaton, a standout in his slapstick works such as Love and Death, is handed one of the most fully-realized lead roles ever concocted for an actress in Hollywood. In its premise, Annie Hall might seem like a classic romantic comedy, but after a few minutes, it is clear that this is not a Howard Hawks screwball trifle starring Cary Grant. The dialogue is quick like the classic screwballs, but laced with acid, melancholy, intellectual references, and a profound irreverence. It is shocking that a film which freely references Bergman and Fellini, Marshall McLuhan, and the JFK Conspiracy would find such a wide audience. The screenplay’s brutally honest and intimate portrait of a relationship indeed recalls Bergman, and likewise, the film’s unorthodox, flashback-laden structure betrays the influence of Fellini. Annie Hall is able to seamlessly integrate high-culture influences through its sharp humor, relatable characters, and its familiar yet magical use of Manhattan and Los Angeles locations.

Unlike Star Wars, it may appear difficult to trace Annie Hall’s influence on subsequent works of cinema. Two common reference points, When Harry Met Sally and 500 Days of Summer, are pale imitations rather than legitimate heirs. The Nora Ephron-scripted “modern classic” mines Allen’s Manhattan setting, Jew-Shiksha pairing, and even a score of Gershwin standards. However, the narrative is tidy, cutesy, and as vapid as a Doris Day-Rock Hudson romp. Similarly, 500 Days of Summer uses its time-shifting gimmick to hide the fact that it is a contrived and rather ordinary romantic comedy. In surprising ways, it is the American independent cinema movement which blossomed in the early-to-mid 1990s that is most influenced by Annie Hall and Allen in general. Despite decades of forerunners, ranging from John Cassavettes’ Faces to Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It, Stephen Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies, and Videotape is often regarded as the initial salvo of the American independent movement; just as Bonnie & Clyde is considered the first New Hollywood film. Soderbergh’s debut boasted sharp comic dialogue, fully fleshed out-characters, an unashamed focus on sexuality, and experimental techniques. All these elements were hallmarks of Annie Hall.

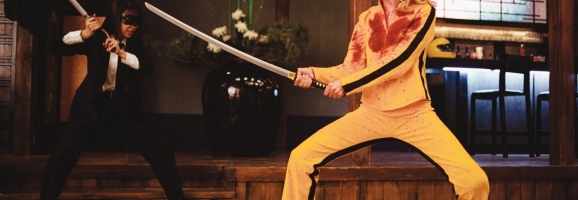

The two directors of this movement who continue to inspire cult adoration are Richard Linklater and Quentin Tarantino. Linklater’s talk-obsessed scripts, romantic nature, and self-conscious intellectualism all point to Allen. The Before series, a trilogy of dialogue-rich romances starring Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke, are the true heirs to Manhattan or Annie Hall. The over-intellectualizing male hero so particular to Allen’s films is legion in Linklater’s cinema, whether this character is portrayed by Hawke or Linklater himself.

Tarantino’s films, with popping colors, high-octane soundtracks, and ruthless violence, may initially appear antithetical to Allen’s style. In Tarantino’s non-sequitors, cultural references, and once again, the endless dialogue, the filmmaker is revealed to be a surprising descendant of Allen. The on-screen persona cultivated by Allen has appeared in many forms over the years, from Ben Stiller in David O. Russell’s Flirting With Disaster and Paul Giamatti in Alexander Payne’s Sideways, to any film starring Jesse Eisenberg. None of these films have broken box-office records, but for thoughtful moviegoers, they are true breaths of fresh air.

With some key exceptions (the shining example being the aforementioned Blue Jasmine), it is true that Allen is a shadow of his former self (his latest film, Magic In The Moonlight, being especially stale). This is what makes his cinematic successors so vital in the landscape of contemporary American film. The two filmmakers working today who are the most heavily indebted to Allen are Noah Baumbach and Nicole Holofcener. Neither are household names, but few directors are more consistent at making witty, intellectual, and humane romantic comedies. In 2013, the same year that saw Allen return to glorious form with Blue Jasmine, Baumbach released Frances Ha, while Holofcener released Enough Said. Baumbach’s light-as-air but resonant film stars Greta Gerwig as an Allen-esque neurotic who struggles to find herself as a post-grad in hipster mecca Brooklyn. Enough Said finds TV icons Julia Louis Dreyfuss and James Gandolfini perfectly embodying warm, flawed, and multi-faceted Los Angelinos. These portraits of romance, whether youthful or middle-aged, are honest, slyly funny, and deeply touching. The influence of Star Wars may have won out in the multiplexes, but in select theatres, films more in thrall with Annie Hall’s timeless grace than Luke Skywalker’s boyish charm are out there to be discovered.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I loved how Woody Allen would talk to the audience like we were in the movie.

Breaking the fourth wall is definitely something that makes Woody Allen Unique!

Rewatched star wars after a couple of years since my last viewing and watched it on blu ray it is brilliant!

The script of Annie Hall is honestly so funny, clever, and witty I could read it as a book over and over again.

Totally. This film has some of the most clever writing of any movie I have ever seen. Unlike most comedies, this film does not go for cheap laughs.

Great analysis here. Both these films makes people of all ages and walks of life believe.

Very unique choice of films to analyze thanks.

I love how you analyzed these movies. Annie Hall is one of my all time favorite movies.

The first film I fell in love with was Star Wars. I saw it when I was 4 years old. It was the first week it was out back in 1977.

“Star Wars” and “Annie Hall” is the type of movies you either love or don’t like.

Annie Hall is a such a different type of movie. The entire layout of the movie is so unforgettable.

Two of the greatest movies ever made.

Annie is Woody Allen at his best.

I didn’t know much about Allen or his works, and I still really don’t. But I liked this movie.

It’s interesting. Star Wars really has had a profound influence on the film industry. This decade had some of the most groundbreaking and beauitful filmography and editing. Before Lucas though, franchises were not really a thing. Now sequels are much more enticing for studios. It’s a shame since more original films have a more difficult time being appreciated now.

I never would have expected to like Woody Allen. There is just something about his nasally voice that sets the expectation of boredom. He’s grown on me.

Way back in 1977, Star Wars literally blew the entire world of cinema out of the water. I was a kid back then but I remember.

I agree. I always saw him a pretentious snob growing up, when it turns out I was the one who needed to grow up and realize how great his films were.

My apologies, that reply was meant for HedyEng. My laptop can be a bit fickle.

I would recommend Annie Hall and SW to anyone who likes to watch good cinematic history.

These two movies are definitely the two starling examples of what made the “Golden Age of Hollywood” so great. Studios realized that the mass-produced, studio-set, films were no longer cutting it for American audiences. It was this realization that really led to them giving no name directors the big budgets that allowed them to create masterpieces like Annie Hall and Star Wars.

It seems weird now, but really all of the successful films of the Golden Age were independent in their own right. They were new ideas from no-names who just happened to receive big budgets from desperate studios.

Great Article! Great Films!

Great article. I wondered about your inclusion of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit as “the indulgent, money-hungry Star Wars of the 21st Century,” though. I’d definitely say the latter is true, but I’d consider The Lord of the Rings a much more sincere venture along the lines of the pretty money-indifferent original Star Wars, which you also mentioned. It’s a nitpicky thing, I know, but it made me wonder what kind of criteria you’re holding these movies to. Do you think they shouldn’t be made at all or just that they should be less greedy?

This is the type of thing I’d expect to find posted on the imdb message boards by some film student – a pure opinion piece that uses derisive terms to describe the achievements of one filmmaker and worshipful terms to describe the other. It comes down to a declaration that the writer doesn’t like the state of affairs in Hollywood and that the public is wrong about what they prefer. There’s nothing informative here. It’s simply one person’s opinion ranted in text.

What Lucas did was to show the studios that there was a huge untapped market of young people. They gave Lucas the rights to the toys! They had no idea. Up to that point young people would go to the drive ins to see Roger Corman pictures. Star Wars woke up the studios, which were in huge transition, to the potential of the youth market (corporations taking over and the Moguls all dying off).

Science fiction wasn’t dead. You have ‘Logan’s Run’ and ‘Silent Running’. The Planet of the Apes films. ‘The Omega Man’, ‘Death Race 2000’ (Corman), ‘Soylent Green’, ‘Slaughterhouse-Five’, ‘A Boy and his Dog’, ‘Rollerball’, ‘The Andromeda Strain’ and ‘Westworld’ (thank you Michael Crichton), ‘Zardoz’, ‘Solaris’, ‘The Man Who Fell Down to Earth’, etc.

Corman always complained that they just took his b-movies and made them into A-movies.

‘Annie Hall’ is Allen’s first ‘mature’ film and this has a lot to do with working with the Cinematographer Gordon Willis and editor Ralph Rosenblum. Willis had a profound impact on Allen (as he did with everyone he worked with). Allen himself admits that before Willis he was doing schtick. After Willis he became a mature filmmaker. Rosenblum talks about ‘Annie Hall’ in his book ‘When the Shooting Stops’. Said that the film was all over the place and was very much shaped in the edit room.

Interesting choice of movies to compare. Very interesting!

This is the first Woody Allen movie that I have seen and it was definitely an interesting experience.

Ah, I appreciate the reference to Linklater, was honestly thinking that right as you brought it up. The before series really is a fantastic reference to the Annie Hall style. Allen’s style of a romance was more about the internal issues of people being together, their differences (though not explicitly said to each other) that bring them together and separate them at the same time. The reason I say this, is because romances before this time focused much more on the third party restraints of two people attempting to be together. Here’s girl and here’s boy, they are both going through so-and-so and now it’s difficult for them to be together because of those issues. In the Annie Hall examples, we hear about the issues of the two, but that is simply ALL we get. There is no third party, only the watcher listening in on the thoughts of the two people, judging for themselves the question of whether the two will end up together.

I find Woody Allen very annoying. People want escapism because the poverty of their lives stops them from doing exciting things. If I had a Ferrari I wouldn’t want a light-sabre. I hope someone wins best actor for a Sci-Fi movie. It takes a better actor to convince an audience that the force is real than an actor dealing with something that is real.

A good essay and an interesting blending of two movies. I remember when both of these movies came out and we waited in line to see them.

I definitely see where Star Wars has more of a focus on special effects such that Marvel, DC, Transformers, et al. followed suit.