Batman and the Problem With Vigilante Justice: A Love Story

“Batman? Batman! Why is he running, Dad?”

“Because we have to chase him.”

In one of the last lines of Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, Jim Gordon attempts to explain to his son why Batman flees the scene only moments after saving the child’s life. Gordon offers an enigmatic answer to his son’s question, acknowledging both Batman’s importance to Gotham and the inherent problem in his mode of operation by referring to Batman as a “silent guardian, a watchful protector,” but also notes that Batman is “not our hero.” This description by Gordon places Batman in a gray area, unable to be fully defined or understood. He does not fit neatly into one particular categorization and is, therefore, problematic. But to whom exactly is Batman problematic? And what is it about Batman that places him behind such an opaque lens? Batman is considered an outsider because, instead of going through the proper channels and managing the situations he finds himself in with a certain amount of decorum, he mercilessly deals out his own brand of vigilante justice. He smashes any and everything in his way while pursuing his ends. Interestingly, it is the same vigilante justice that Batman supplies that endears the Caped Crusader to so many readers (and viewers). So why must Batman endure constant hounding from the authorities? And what does it mean that fans of Batman are so quick to vehemently defend his actions when the authorities label him as a criminal?

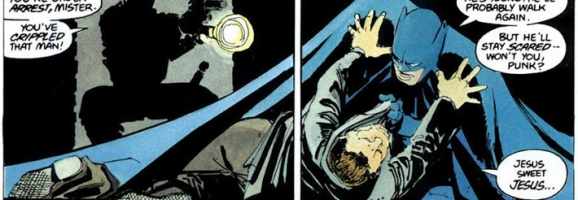

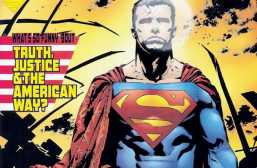

Batman is a character that takes matters into his own hands. He does not wait for approval and effectively answers to no one. When a problem arises, he rises to the occasion and remedies the situation, often times to the chagrin of the local authorities. Much like many other comic characters such as Spider Man or V from Alan Moore’s V For Vendetta, Batman is often portrayed by the authorities as a pariah and a menace to society. Just as Jim Gordon tells his son that the police must chase Batman, others are as well. But why? It seems that, in the worlds in which these characters exist, the authorities need all the help that they can receive. Therefore, it would make sense that characters like Batman would be lauded, not reprimanded. That is, however, not the case. Batman does not play by the prescribed rules. Were he to follow the regulations of the authorities, perhaps they would have left him to his own devices. Frank Miller explores the possibilities of superheroes coexisting and assimilating in everyday society in Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. Superman, representing an obedient faction of super heroes implores Batman to submit to the will of the United States government and obey their rules. He says, “I gave them my obedience and my invisibility. They gave me a license and let us live. No, I don’t like it. But I get to save lives… and the media stays quiet.” He goes on to say, “They’ll hunt us down again… because of you.” Superman, in this instance, is the perfect example of the lackey that the government wants superheroes to become. He acts according to the will of the President, and in return, is allowed to continue his work of saving the planet from ever impending doom. The fact that the government would attempt to interfere with the going-ons of such a class of people is laughable, but made real in Miller’s book. When Batman does not concede to their wishes, they call in Superman to put an end to Batman. Miller’s commentary is the crux of the problematic nature of Batman. He cannot be controlled.

Batman’s unwillingness to accept being controlled causes three major problems for the government. First, Batman is not interested in politics. He is not running for elections. He has no constituents to answer to. He has no ulterior motives other than bringing hardened criminals to justice. When the government is unable to control Batman, they are unable to use him as a positive tool for their political rhetoric. They are unable to stand upon a pedestal and hail Batman as their creation, their beacon of hope for the citizens of Gotham that keeps them safe. Even Jim Gordon, in The Dark Knight, acknowledges Batman’s diametrical opposition to the politics of Gotham when he states that Batman is, with Gotham at its worst, “the hero Gotham deserves, but not the one it needs right now.” Batman is not the knight in shining armor to bring peace to the mean streets of Gotham through heady political maneuvering. He is The Dark Knight, gritty and part of the salt of the underworld, that grinds justice out of sludge.

The second problem Batman creates is that he presents a counter-argument to the ability of the government to safeguard its citizens. While Batman obviously cannot be everywhere, he saves countless lives throughout Gotham through his exploits. The protection of Gotham is first on the agenda for Batman. It was, after all, a senseless act of violence that became the impetus for Bruce Wayne when he was a child that would eventually lead to his becoming the Batman. Desire to rid Gotham of all those bent on destroying the peaceful social order is what drives Batman. The fact that he is so good at what he does serves notice to the Gotham authorities, presents them in an unfavorable light, and thus creates the tension that leads to Jim Gordon’s statement about Gotham’s finest having to chase Batman. They must chase him because without doing so, they become irrelevant. The only way for the government to attempt to maintain control is to paint Batman as a villain, as someone who puts his own desires well before concerns about the laws and enforcement agencies designed to protect the citizens of Gotham.

Lastly, and most importantly, Batman is problematic to the government because he gives the people back their power. The citizens of Gotham feel as if they have been completely stripped of all of their power, of their voice, to stand up against the injustices committed against them both by criminals and the government itself. Batman’s public display of vigilante justice provides an outlet for the public to understand that they do not have to hide in the shadows and feel as if they are perpetual victims of an impotent system that fails to protect them. Lana Lang, in TDKR, says of Batman, “A man has risen to show us that the power is, and always has been, in our hands. We are under siege — He’s showing us that we can resist.” Batman gives the people the power to fight back, to assail the assailants, to rebel against a broken system. This aspect of Batman is particularly problematic for the authorities because an angry population that has suddenly found its voice is a very dangerous thing in the eyes of a government. When the oppressed finally rise up, change happens. And nothing stifles the oppression of a stagnant government like an angry populace bent on having their lives returned and restored to some true semblance of freedom.

So what does it mean that we love Batman as a character despite the fact that his actions are, by all accounts, illegal and, at the very least, morally questionable? I believe that we love Batman because somewhere inside of most people resides a tiny piece of what Batman represents. Down deep, many of us wish that we could rectify many of the societal problems that our governments are either too afraid, too inept, or too deeply invested in to change. We want to fly down from on high and deliver a swift and silent roundhouse kick of justice to those wreaking havoc throughout our societies. We want to be The Night. But where we fall short, Batman delivers. However, despite the fact that we cannot actually be Batman, we can learn from him. We can learn that the ability to change our world exists within us, that we do not have to be afraid. We can, as Lana Lang suggests, resist. And that is why Batman, and his vigilante justice, is simultaneously so inherently problematic and yet so very important. We rally around this masked vigilante, not because he breaks the law, but because, through the way he fearlessly clings to his own moral compass and breaks through hegemonic rhetoric, he becomes a rallying cry for change and accountability. And for that we should all throw up the Bat Signal.

Works Cited

Miller, Frank. Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. New York, NY: DC Comics, 1986. Print.

The Dark Knight. Dir. Christopher Nolan. Warner Bros. Pictures, 2008. DVD.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I think some young people have the intellect to cope with violence. Others do not (perhaps it’s the parents). i.e. they think it is acceptable to maim and kill people indiscriminately as in films. Though I guess, knowing what a film is in the first place helps.

Batman, I would guess, is almost in his 40’s. Batman has lived, so he knows better how to control his fear and confidence. Key to dealing with potentially dangerous situations.

I tend to agree with you. Most kids can handle violent media perfectly fine. I think the rest you mention usually suffer from a lack of decent parenting. There are obviously some exceptions to that, but I think that’s where the problem generally lies. Batman is interesting in this regard though, because he is so incredibly violent but (typically) goes out of his way to not kill people. A little morally ambiguous, I guess, but interesting nonetheless.

Now don’t get wrong, but I’d don’t think a good ole sense of social justice isn’t important to a superhero narrative…

…but I do think that the practice of social justice by superheroes, as in the real world, necessitates navigating complex moral/ethical problems.

I completely agree! I think that there is a lot to say about what it means that Batman does what he does. It would be insane If someone were to walk out in the streets of the city I live in and start smashing up guys holding up gas stations. I think that’s part of what makes Batman so cool to study though. Taking a look at those moral/ethical dilemmas that surround the motives and actions of Batman is really interesting.

One problem I have with the postmodern approach of a lot of comic book writers and films like the Dark Knight is that it assumes that the more interesting story is one where the character trying to espouse moral and honourable principles is a fanatic adhering to an immutable code.

An under-explored avenue in mainstream superhero fiction these days is where the traditional monastic hero is a fundamentally moral figure trying to take moral action in a morally ambiguous world, and which juggles the conflicts therein. A far more cuddly approach on paper, but one which has been explored in comics with far more success than in film.

Depsite Watchmen’s accolades, some of its impact appears to be in unintentional directions – namely, focused on the darker take on superhero fiction, encapsulating realistic murder investigations, the Steve-Ditko-inspired moral crusader Rorschach and the technological and human consequences of a nuclear superman. Whereas as he has since repeatedly stated, Alan Moore’s intention was to try and tell stories about normal people in a recognisably comic-book setting. But rather than a generation of writers inheriting from Moore and Will Eisner, a wave of writers have reached acclaim with a far shallower, more cynical view of the genre, spawning a glut of equally unbelievable superpowered characters who either nurse phoney emotional hangups or who become complicit in rape cover-ups (as in DC’s hilarious misfire, Identity Crisis).

Creators like Paul Grist, Mike Mignola, Mike Allred and Darwyn Cooke are still churning out brilliantly entertaining and emotionally engaging tales about characters who somehow manage to be compelling without being torturers or sex pests. However, because of Hollywood’s recent fixation with bad-assery and a pop culture locked in an Oedipal rejection of hero figures, these don’t get much of a look-in in the mainstream media. For shame!

That’s really interesting. I agree that there does seem to have been a shift in recent years concerning the state of the hero in mass media. Half of the story seems to revolve around the fact that the hero of the day is having to fight on two fronts to even stay on their feet. I don’t think I can make a call on which take is better or worse, but I think it’s important to ask why that shift has occurred. Of course, speaking of Alan Moore, there are the anti-heroes like V from V for Vendetta as well. Personally I liked Moore’s handling of that character better than in the film. But where does a character like that fall in this discussion?

One of the key defining characteristics of modern superheroes is their refusal to kill. Batman carried the paralysed hectoring form of the Joker through the himalayas for months rather than let him die, and even in the films spares Heath LEdger’s Joker – oh the irony. He also refuses to have anything to do with guns.

Okay, in practice this is because it means you don’t have to keep re-inventing baddies every month because they keep dying, but its still wrapped up in good intentions.

Sure, practically speaking, it would not make much sense for any hero to kill off their nemesis because at some point there would be no need for the hero, both in terms of writing a story and logistically wherever the hero resides. There would be no use for them anymore, much like how Gotham feels pre Bane in Dark Knight Rises. In reality, their refusal to kill is, in a sense, probably the only thing separating characters like Batman from their counterparts, with the exception of a Joker type character that is on a whole other level of evil from most. As far as the guns go, Batman did start with a gun, unless I’m mistaken. At that point he isn’t much different intrinsically from the criminals he captures, with the exception of differences in methodology and purpose. I didn’t know that about Batman carrying Joker through the Himalyas. Their relationship is really fascinating. Thanks for the response!

Yes, Batman used a gun frequently in his early days. Stopped by editorial mandate to keep the books less violent. Detective Comics was a very dark book early on, and Batman was not opposed to lethal force.

This was an interesting article. I think more is being attributed to classic characters in order to retcon in more depth, as a result, they become less accessible to modern audiences unless they are sent too far into the dark (Man of Steel, anyone?)

I think Miller’s DKR is the best modern Batman, and a good example to use in this context. Kind of a bummer that there have not been more stories of equal quality for Bats in recent years.

Thanks, Taylor. I agree about DKR, and I too wish that more was being done in this genre. People are often surprised by some of the material that has come out of the graphic novel. Some of the smartest books I read through college were exactly that. Sadly they often come with a public stigma just because there are pictures to go with the words and the protagonists are usually wearing tights. Perhaps it was the times? As I mentioned in another comment, the 80’s were a really great time for the graphic novel. And there was still a lot of nationalistic rhetoric flying around at that time. There is obviously still a lot of political rhetoric being used in regards to the American people, but I believe that the narrative has changed. Perhaps the right storyline to match the current mode of political rhetoric hasn’t been found yet. Here’s to hoping though.

I remember when Robocop came out there was a huge fuss made about how violent it was. However, if you actually watch the film with brain engaged you’ll see that rather than being an orgy of violence, the movie is actually a deeply satirical critique of 80s right-wing pro-Statist, US propaganda. Where the government-serving mainstream media of the time painted the US as a nation over-run by criminals, Verhoeven retorted with his vision of a world where powerful men use the fear of crime as a means of social control and money-making. The really nasty violence in Robocop is carried out on behalf of the State – that’s what the film’s really about.

In the Batman world of the new millennium, evil is an intrinsic part of human society and corrupts the powerful just as it does the weak. Even the prospective White Knights we vote into power can become murdering lunatics given certain circumstances.

The real dilemma is this: do you the viewer, as a civilian, accept the mainstream dogma and avoid the inevitable by blowing up the criminals before they can blow you up, or do you act as a moral agent and risk your own death on a matter of liberal ethical principle – namely that criminals are still humans, even if they have committed criminal acts. Criminals neither deserve to die nor will they unfeelingly kill a boat-load of people to save themselves. Batman believes that placed in this situation, humans will choose to reject the Establishment position and allow their own ethical instincts to stop them blowing each other up.

Thats a really interesting point and juxtaposition. I’ve never really looked at Robocop in that way, but admittedly, it’s been a long time since I have seen it. I think that the politics of the day, much like with Robocop, had a lot to do with the type of things that were written, particularly in the 80’s. There were a lot of really smart and engaging books written then (DKR, V for Vendetta, Watchmen, etc) that seem to resonate your point. Thanks for your response!

The dilemma was brilliant: blow up the criminals before they blow you up because they deserve it more than you do, but you can only do this if the criminals fail to meet the low-expectations the other passengers have of them; otherwise they surely would have immediately over-powered the guards and set it off.

Well-written and quite deeply enjoyable. Looking forward to your next article.

Thank you very much!

That was a great read! I feel like I can agree with the notion that we all kind of really want to be a little bit of Batman. I remember this one time that I got mugged and my phone was stolen, I wish i had the capability to do something about it. ANYTHING about it. It was futile, but I can very much see your point.

Thank you very much, Iamberto, although I am sorry to hear that you were mugged once!

Great read and some great points. I think, for me, the idea of loving Batman whilst questioning his actions becomes most problematic when viewing his “moral code”. If we can accept him being the hero gotham deserves, a vigilante who has put himself above the law, then we have to accept the fact that Batman does not totally fulfill the role that he has prescribed for himself. Through his affluence and subsequently his access to technology, Batman has put himself in the greatest position to save the most amount of lives. However, when it comes down to it, Batman is reluctant to actually do what it is that Gotham deserves. Take for example, the scene where Batman (On the Bike) and the Joker have a face-off, with the Joker shouting, “hit me”. If Batman were to actually hit the Joker, that would, ideally, be the end of all the chaos and dying, at least in that circumstance. However, because of Batman’s moral code, he swerves, and ends up playing into the Joker’s hands. The question becomes, if Batman were truly Gotham’s hero, shouldn’t he kill the Joker in order to save the most amount of lives? Although I respect Bruce Wayne and his morals as the Batman, perhaps it is actually those same morals that perpetuate death and violence in the first place. I really don’t have a true answer, and this is just food for thought, but this is always something I’ve been torn about in regards to Batman. Great article, my apologies if I’ve digressed from the original topic!

Not at all! You bring up some fantastic points! That’s a really interesting thought, that Batman’s moral code against killing actually perpetuates more killing. There is probably an entire discussion that could be had just on that thought. Thank you for the response!

Interesting.

We delude ourselves if we think that the “Superheroes”, as they act in recent movie portrayals, are the moral centres of the story.

The centre of the movies is, in fact, the immoral glorification of angst, pessimism, amoral lifestyles, hardware, villainy, torture; all posing as ‘complex moral dilemma’.

The heroes are the technology, the glamour, the glitz and the grime.

Jonathan,

I cannot agree more. I enjoy how you work through the paradoxical Batman. As you mention Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, I wonder what you think of Gotham’s posthumous embrace of Batman in The Dark Knight Rises. I am specifically thinking of the statue scene during the film’s concluding montage. Has Batman finally escaped the grey area you put forth into the embrace of urban (urbane) consciousness? In death, has Batman escaped opacity? Can he now be acknowledged as the “the rallying cry for change and accountability” within the hegemony? Nolan is doing some fascinating things with the Batman Mythos in his trilogy and I would love to hear your thoughts around this. Anyway, thanks for the great read!

Cheers,

Sean

^Jonathon (not Jonathan!)

I am more of a 60’s TV Batman fan… WHAM, SPLAT, OOF! 🙂

I think most of us can relate with Batman because most of the story line focuses on redemption as well as fighting your own inner demons. One of the reasons why I’ve always gravitated towards the character is because of the fact that while he may not have any superpowers, his own humanity and his wit has saved him a couple of time when fighting crime.

This is a very interesting article. I feel like two arguments can be made. One, vigilante justice is needed in comic books because villains in them have resources and abilities police forces just do not have. Therefore, superheroes, who match these resources and abilities, are needed to come in and stop them. But another argument can be that vigilante justice can be a functional concept even in our society. Merely two days ago a news story came out about how Mexico legalized vigilatism and as a result, a huge cartel leader was captured.

I really like how you describe this gray area where Batman seems to be in an eternal struggle. That difficulty he has in very much his appeal, I think. When you look at a film like the new Superman, where Christopher Nolan was an executive producer, we BEGAN with the opposite sort of struggle; Superman had the desire to correct the wrongs of society and it was well within his power to do so. I think what was beautiful about Batman aging in the Dark Knight Rises in particular is how he regains that same desire to stop evil but struggles to meet that desire with his physical power. Superman, in my mind, could never reach the rich complexities of Batman as you have described.

This is a difficult subject because we as the readers want to view Batman as the Hero. We sympathize with his past and convince ourselves that what he does is for the good. If this actually occurred in real life however, we may not take it the same way. Part of the reason why we support batman is because he is a symbol in a story that represents doing what is necessary for the sake of justice. still, if we had a vigilante like batman today in real life, we would probably be worried for our own safety. Some of us might even think it would be funny if a masked man went running around and beating up bad guys. But, there are also many things that need to be taken into consideration. First, the fact that this guy is dealing with a traumatic past and feels responsible not only for his family, but for all of those that feel the same way he did when he watched his parents die. He also realizes that he has money to do with what he pleases. This is a guy that is in complete control of his life and the world he lives in, and he has a damn good reason to do what he does. Bruce Wayne knows that Gotham is a corrupt and crime ridden city that is beyond the help of the police. Although he is a rich man that is living it up at Wayne manor. He can relate to the common person in Gotham and the fear that they are living in. He also has his rules such as not using guns, not killing the people he catches, and working in accordance with the police. His sense of justice is not as vigilante like as we think. He seems to simply stream line what the police try to do, only without having to answer to a higher authority before he strikes.(Which is why it is so effective). I feel that batman has a right to do what he does because he has experienced the wrath of Gotham personally, he can relate to the people, he knows the police don’t have enough efficiency, and he has the resources to do so.

Batman is a good introduction to more moral complexity than the old black and white “good is good and evil is evil” tales we have seen in some books.

Great job Jonathon.

I enjoyed your analysis of “our” connection with Batman. I have always been drawn to him and I agree with you that Batman is the hero we want to be. Batman empowers us to have an opinion, to be active in our community, to take control of our life and support our community.

Admittedly we can’t all be Batman. We are more likely to volunteer at a soup kitchen or vote in our local elections or coach our kids sports teams; we cannot all “fly down from on high and deliver a swift and silent roundhouse kick of justice to those wreaking havoc throughout our societies”, but that is why we need Batman.

Batman’s existence as someone who can act without borders is what makes him so absolutely brilliant. I particularly loved the personal connection made between Batman and how we relate to him. What makes him especially brilliant is that, although he acts within his own rules and regulations, he is still very, very human. Indeed he has the money that a normal human does not have, he is still limited as a human.

Although Batman man is my favorite superhero, I have definitely felt the same way about him for a while. Your article covers the issue of his modus operandi very well.

I think Batman is so popular to our society because of the third reason you stated: that he gives power back to the people. Even though Batman is hated by the government, he encapsulates our democratic ideals, namely that the people are in charge. After all, Batman is just a regular man who saw a problem that needed to be fixed and fixed it regardless of what the world told him. Batman as a character should inspire all of us to go out in the world and make it a better place rather than wait for the authorities to do something. That’s not to say that we should go around and potentially get ourselves killed. Rather, Batman in relationship to other super heroes says that someone doesn’t need superpowers to stop criminals. At the same time, we don’t need a badge to make the world a better place.

I definitely feel like Batman is arguably the most relatable hero. Batman is not a superhero whose powers were granted to him by some sort of accident or by any other supernatural means. Its hard for a person to connect to someone like Superman because none of us know what its like to literally be able to do anything. Batman is merely a man who suffered an enormous emotional tragedy and is trying his best to make sure that doesn’t have to happen to anyone else.

I’m wondering what Batman’s association with the Justice League implies within the context of vigilante justice. With the upcoming Batman vs. Superman we will probably eventually see more of that relationship that you mentioned where Superman wants Batman to be subjugated by the government like he is. But considering Batman eventually does become involved with the Justice League, does that mean he gives up vigilante justice? Or does he just recognize a greater threat (aliens are quiet different from street criminals).

I think that this all is very true and very educational. I believe that if someone was to rise to the level of Batman or even a deadpool ofsorts that it would do a lot of good for our country, spirit, youth and hope. Maybe someday someone will.

What?

Batman doesn’t kill, but , like remember The Dark Knight Rises? It should mean to do things that you can do to make a better living for the world’s inhabitants, doing things that no one, even local authorities can do.

If you want to kill a criminal to make it a better place, think again. During an interview with Christian Bale with in the program, Charlie Rose for Batman Begins, he said, “As the Batman, and I kinda like calling him a creature. He’s virtually demonic,you know. In his rage, but with the great philanthrophy of his father. You know, talking in his ear, all the time, reigning him in. And it’s stopping him from going too far and becoming a force of great destruction in which he’s capable of.” What we are capable of doing, set very strict limits like inspired by Batman, although vigilante justice is illegal. But why is it illegal? In the real world? In the United States?

Those who claim that vigilantism’s illegal are self-righteous goody-two-shoes.

Does it mean that Batman deals with the same conflicts we deal with every day, in our lives like over what’s right and wrong. Like, in real life, if you ever take a life, does it mean there’s no going back? Christian Bale says about Batman, fights mentally, and also physically, but emotionally as well. Like the conflicts Batman deals within himself.

Ben Affleck as Batman? How? After Christian Bale? When? The new Batman vs Superman: Dawn of Justice?

It’s worth pointing out that Gordon is wrong when he says, at the end of The Dark Knight, that Batman is not the hero that Gotham needs. This, of course, becomes clear in The Dark Knight Rises.

Batman’s vigilantism only works because he is smarter, better equipped, and has more integrity than regular law enforcement.

Weird oh your a geek just say one of the movies not the dark night geek

Weird oh you should just say one of the movies not the dark night you dumb geek go to your momma your not ready for the real world

Hypocritical much?

Go bat man die superman bat man is the king of all time

I love bat man

I love you