Does The Beat Generation Still Matter?

As difficult as it is to imagine in the 21st Century, there was once an age where adolescents were transfixed and enraptured by literature. This literature did not tell simple, derivative tales about lusty vampires or wizards and wizardry. Conversely, these writers who captured the youth of America asked profound and challenging questions about identity, sexuality, bureaucracy, and religion. When re-read years later, these novels, essays, and poems may begin to appear naïve. Yet, for any individual who must endure the bewildering time frame that spans from age 13 to 30, these post-war relics are timeless and deeply resonant.

This phenomenon that swept the nation and anticipated the 1960s counterculture, is, of course, the work of “The Beats.” Scorned by previous generations and largely ignored by much of mainstream society, it was a literary movement that was highly polarizing. The divisive nature of the Beat writers, who came to prominence in the ’50s, reflects an age in American history that was more fractious than almost any before. Tides were turning in the U.S. at a rapid pace, and although it took most of the nation until the ’60s to realize this, readers of the Beats were among the first to sense these seismic changes.

Glancing at the works of the Beat Generation will take readers back to a volatile yet optimistic time. During this generation, the nation’s most detrimental flaws were openly examined, with the sincere belief that these flaws would be mended and lead to the formation of an ideal society. In the 21st Century, however, a reader does not need to know an iota about the sociological influences of the Beats to engage with their literature. Readers merely need to feel alienated and questioning, cynical yet romantic, searching but grounded.

Hollywood has tried to make The Beat Generation palatable for contemporary audiences with the little-seen films On The Road and Kill Your Darlings, but the literature itself is the ideal introduction to this singular literary movement.

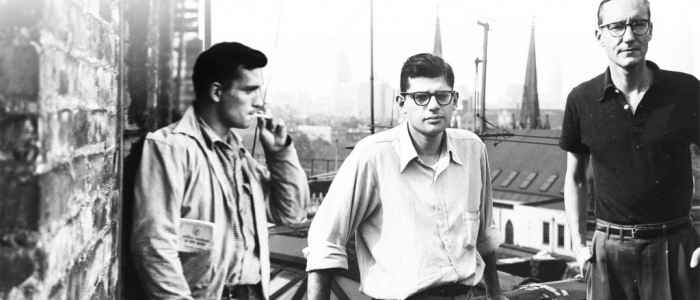

There are three writers who most prominently defined the Beat ethos, and these scribes deserve a fresh look by the youth of the 2010s.

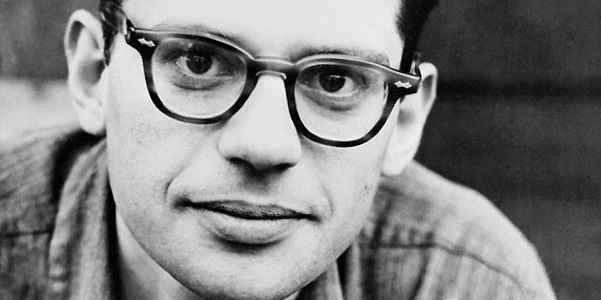

Allen Ginsberg: I Saw The Best Minds of My Generation…

For college students in the post-war age, there was nothing as simple yet mind-blowing as reading poetry while walking around a lush campus in Berkeley or Boston. This activity may be primarily replaced by glancing at an iPhone at contemporary universities, but the level in which poetry enchanted and stimulated students in this era cannot be overstated. Before World War I, American Poetry was but a pale imitation of the stunning wealth of British poetry, with the key exceptions of Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman, two poets who remain among the most distinguished and distinctive writers America has ever produced. Following the turn of the 20th century, however, American Poetry flourished, with voices as disparate and startling as Robert Frost, William Carlos Williams, and Langston Hughes permeating the world of literature. Following World War II, the new and radical changes slowly but surely seeping into society affected contemporary poetry.

Few poets reflected this societal shift more vividly than Allen Ginsberg, whose poem “Howl” remains perhaps the best known work of the Beat Generation. Starting out as a devotee and protege of Williams, whose epic Paterson clearly inspired the fellow native of this New Jersey municipality, Ginsberg soon began developing his own idiosyncratic, experimental style of poetry. In the years between his tenure as an impressionable undergrad at Columbia (where he met William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, the subjects of the following sections) and the publication of “Howl” in 1955, Ginsberg morphed into a hardened, outraged cynic.

While many of Ginsberg’s fellow Americans were basking in the glow of apparent prosperity during the Eisenhower era, the poet dared to probe the seedy underbelly and fallen dreams of post-war America. The opening lines of “Howl” are as iconic as anything by Frost or Dickinson; “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix, angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night…” Angry but compassionate, musical yet discordant, it is truly the work of a poet who is as intellectually engaging as he is lyrical. Ginsberg’s verses read as a potent mixture of jazz hop and protest music fieriness; is it any wonder that he became close friends with Bob Dylan?

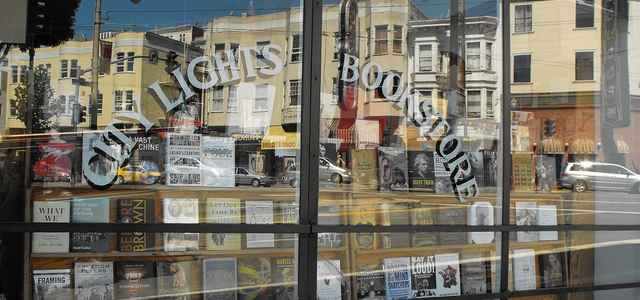

The poem proved to be controversial for its homoerotic imagery, and was one of many innovative works of literature to find itself in a censorship battle. (In June 2015, a high school teacher was fired for reading Ginsberg’s “Please Master” in class, speaking to the social conservatism the poet railed against). In the poem’s autobiographical elements, social criticism, and unfiltered sexuality, it also is emblematic of nearly all the key aspects of “Beat” literature. Ginsberg became the first true celebrity among the Beats, and although he met Kerouac and Burroughs in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, all three would become associated with San Francisco’s North Beach. More than a decade before Scott McKenzie exhorted visitors to wear “flowers in their hair,” San Francisco became the center of “hip and now.” For quite a few years there, it seemed like this small, quirky Northern California city would eclipse New York as the nation’s cultural capital.

None of Ginsberg’s poems contained the same impact as “Howl,” and for many he was a poet more read about than read. Yet the majority of his poems were of exceptionally high quality, whether celebrating Eastern spirituality, his literary forbearers, or his acceptance of his homosexuality. Both his love of Eastern religions, in particular Buddhism, and his openness about his “deviant” sexuality, inspired much of the ’60s counterculture mentality. Ginsberg could famously be seen dancing to “I Want to Hold Your Hand” at a café or gyrating to a Grateful Dead concert in Golden Gate Park. Yet his work is not merely a fossil from the flower power age. For individuals searching for meaning in a dispiriting world and trying to come to terms with all components of one’s identity, there are fewer sources of solace than a poem by Allen Ginsberg.

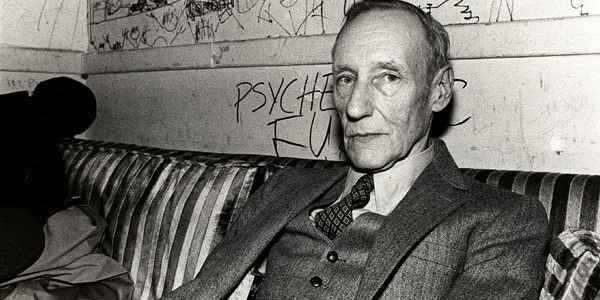

William S. Burroughs: A Queer Junky Forever Lost in Interzone

If Ginsberg’s literature was groundbreaking in its exploration of homosexuality and critique of contemporary society, the work of his colleague William S. Burroughs was positively earth-shaking. Freely expounding on homosexual intercourse, drug use, and the evils of technology and bureaucracy, Burroughs’ novels, essays, and memoirs constituted one of the most distinctive and penetrating bodies of work in all of modern American literature. Ginsberg’s poetry is steadfastly tied to his era, yet the literature of William S. Burroughs appears to be beamed from an obscure planet in the distant future.

His earliest works contained all of the taboo content Burroughs is known for, but none of the experimentation with form. Queer and Junky, both written at the dawn of the 1950s, are as blunt and economical as their titles. Both were non-fiction works, despite the attempt at disguising each book’s protagonist as one “William Lee.” Vividly depicting Burroughs’ real-life adventures exploring drugs and his own sexuality in locations as diverse as Manhattan, New Orleans, and Mexico City, Queer and Junky combine the straightforward prose of Hemingway with the gritty candor of Henry Miller. While Junky was published (to little notice) in 1953, Queer was not published until 1985; a testament to how ahead of his time Burroughs was in his uncompromising portrait of homosexuality.

It was not until 1959 when Burroughs gained widespread recognition- and notoriety. His novel Naked Lunch (like “Howl,” a seminal statement of the Beat Generation) was published to much controversy, in addition to rapturous acclaim by the alternative press. Structured in a series of surreal, apparently disconnected vignettes, Burroughs’ masterwork frequently shifts from gritty realism to nightmarish science fiction. Starting with a harrowing account of heroin addiction to rival Junky, Naked Lunch careens to terrifying visions of a society overrun by bureaucracy and technology, existing in a halfway reality termed “Interzone.” Burroughs has insane fun in sequences detailing homoerotic orgies and bars populated by cockroaches, but his intent is completely serious. Like all great writers, Burroughs uses sci-fi as a vehicle to express his warnings of the direction modern society was swiftly heading in. The controversial content inevitably led to censorship, but in a landmark case, the Massachusetts Judicial Supreme Court defended the right for Burroughs’ novel to be read freely, affirming it as a “socially important work.”

Burroughs further experimented with content and form alike in his “Cut-Up” Trilogy, using a technique in which new text is formed from cut and re-arranged words. This off-kilter style renders the novels in the trilogy his most disorienting and alienating, but his themes of social control through technology has rarely been expressed in a more lucid manner. After the 1970s, Burroughs was known more as a cultural icon than a writer, appearing in Drugstore Cowboy, Nike ads, and an R.E.M. song. It is likely that contemporary readers will hear the name Burroughs and think of Augusten (author of Running With Scissors), rather than the Naked Lunch firebrand.

However, novels ranging from William Gibson’s Neuromancer to Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow reveal the transparent stamp of William S. Burroughs, and it is clear in the 21st Century that the writer was prophetic rather than paranoid. A contemporary reality where technology is often used to repress rather than liberate is strikingly akin to the fictional creations of a writer who defined his era as much as he transcended it.

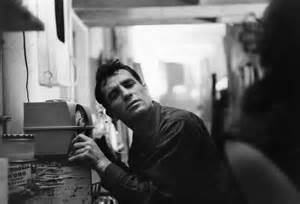

Jack Kerouac: Writing, Not Typing

Jack Kerouac may be the writer who is most firmly tied to “The Beat Generation,” but in many ways he is the least representative of the Beats. Kerouac was socially conservative and heterosexual, while his work lacked the anger and pitch-black surrealism of Ginsberg and Burroughs. What he did share with these writers (and friends) is his literature’s spirituality, freedom, and search for meaning in a fractured American society. Kerouac was a Vietnam supporter who disdained the “hippies,” but, paradoxically, his novels, especially On The Road and The Dharma Bums, are often considered the first novels of the 1960s (despite both works being published in the late ’50s). What is most remarkable about these novels’ apparent prescience is that they were actually begun as early as the late 1940s. In an era defined by antiquated middle-class values, Kerouac was taking speed and popping out playful, exuberant literature about hitchhiking, alienation, and casual sex.

These three elements of course appealed to the “flower children,” but the lasting power of Kerouac’s novels is in their compassion, spiritual nature, and youthful energy. On The Road, along with “Howl” and Naked Lunch, is a defining work of not merely the Beat Generation, but of post-war American Literature in general. Published in 1957, almost 10 years after Kerouac wrote it in a notorious three-week binge, On The Road is an autobiographical work detailing a series of hitch-hikes the writer took across America. The prose style is notoriously scattered and self-conscious in its refusal to be “literary.” Truman Capote, whose novels Other Voices, Other Rooms and Breakfast at Tiffany’s made him a literary superstar in the late ’50s, famously derided On The Road as mere “typing” rather than writing. The writing style may seem frantic and shapeless, but it suits a novel that is attuned to the freewheeling disorder of life, rather than a pat, linear narrative.

In many ways, Kerouac’s breakthrough novel does for “The Beat Generation” what Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises did for the “Lost Generation” of the 1920s. Both works are roman a clefs, revolve around protagonists who aim for self-discovery by travel, and are written in a direct, lean style that eschews flowery prose. While The Sun Also Rises is today a consensus masterpiece of modern literature, On The Road remains divisive. However, it is unlikely that any young American will fail to see a bit of themselves in narrator Sal Paradise (Kerouac himself) and the unforgettable Dean Moriarty (key Beat poet Neal Cassady). Sal’s thoughtful, impressionable narration clashes with the impulsive, full-on ID personality of Dean, making for a timeless portrait of friendship and the risk-taking excitement that the open road represents. Gliding from New York to Denver to San Francisco, with brief sojourns into Mexico, On The Road is the ideal substitute for a cross-country road trip.

His most famous novel may be his most accomplished work, but Kerouac’s oeuvre contains a lion’s share of worthwhile books. The aforementioned The Dharma Bums is a fascinating, if occasionally adolescent, portrait of Buddhism in post-war San Francisco, while The Subterraneans is a brief headlong rush about interracial romance and loneliness. Dr. Sax and his debut The Town and The City are old-fashioned, Thomas Wolfe-inspired portrayals of his hometown of Lowell, MA, which further speak to Kerouac’s ability to transcend his Beatnik labeling. The novel that stands alongside On The Road as a remarkable literary accomplishment, and the work that shatters the youthful naiveté inherent in much of his literature, is Desolation Angels.

At first, the 1965 (written in 1957) novel seems like a Kerouac greatest hits sampler; the novel is set in the writer’s beloved San Francisco and the Pacific Northwest, while the characters are young, spiritual, and aimless. However, as the novel progresses, Kerouac delves into the depression and alcoholism prevalent in the Beatniks’ lifestyle, in a fashion far beyond the implicit hints embedded in On The Road or The Subterraneans. Desolation Angels contains the same travelogue structure of Kerouac’s earlier work, but rather than carefree, it is sobering (despite all the alcohol) and quietly somber. The Dharma Bums may have explored Buddhism in a simplistic, superficial fashion, but Desolation Angels reveals Kerouac’s growing disenchantment with religion. The novel ultimately affirms that spirituality need not contain the division, bureaucracy, and arrogance of organized religion. The work is a requiem for all the values of On The Road; freedom, youth, flesh, and the spirit are all revealed to be empty and futile. Years before John Lennon sang “The dream is over,” Kerouac wrote about the downfall of the counterculture dream- years before it came to fruition.

In this fashion, the seemingly dated literature of Kerouac was actually ahead of its time. To an extent far greater than Ginsberg and Burroughs, Kerouac’s novels are fully attuned to the uncertainty, romance, and intrigue of youth; in this or any age.

What these three defining writers of “The Beat Generation” share is their relish to defy conventions, question the deeply held principles of American society, and evoke the liberation and intoxicating fears of youth. For many, “The Beats” may seem juvenile, wrongheaded, and frivolous. Admirers of the formalist literature of Henry James or Marcel Proust are likely to withdraw in disgust at the sight of a sentence of prose by Kerouac or Burroughs. For youth around the world, and those who prefer to stay forever young, the gleeful experimentation and life-affirming majesty of the Beats will always live on.

Works Cited

Charters, Ann. The Portable Beat Reader. Viking International, 1992.

George-Warren, Holly. The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats: The Beat Generation and American Culture. Hyperion, 1999.

Johnson, Joyce. The Voice is All: The Lonely Victory of Jack Kerouac. Viking, 2012.

O’Hagen, Sean. “America’s First King of the Road.” The Guardian, 2007.

Savage, Bill. “Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and The Paperback Revolution.” Academy of American Poets, 2008.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

wannabeat more deadbeat than beat

I sense when reading Jack’s writing a rhythm going on that I get when reading no other writer. If critics know of any other writer (maybe Shakespeare) who write to a rhythm then please tell me. For this quality alone I feel Kerouac is uniquely talented among writers. This is why he doesn’t use a lot of full stops, commas etc. ‘cos it would break that rhythm. Maybe it was the drugs he was writing under (the influence of) that supplied that rhythm in the way that on speed you often find yourself chattering your teeth to a rhythm.

I always got far more out of William Burroughs work than from any of the other Beats – though I must confess to a liking for Corso.

Burroughs was the only one who could compare with someone like Genet in terms of going to hell and back.

Kerouac wrote one good book. On The Road.

I used to know the last paragraph by heart. That book is as good as anything Capote ever wrote, for all his witty little digs at Jack.

A friend of mine told me he wrote to Ginsberg and was pleasantly surprised to get a reply and apparently they corresponded for some time

Heroes!

There was a particular sense of urgency and vibrancy about much of the beats work, it comes from walking the walk as well as talking the talk.

Allen Ginsberg, sticking up for real freedom by his example.

Most of the Beats were bad writers.

The major exception (although i’m not sure everyone considers him a beat) was Bukowski.

That nasty old pervert could write.

When I first read On The Road aged 16 I felt it held a mirror up to me far truer than school, the work world, or even my family was giving me. It confirmed how I felt about the world.

He was great to read in my early twenties. But since then I have moved to more mature writers and serious writers. i think he was too busy hanging out with the beats, to be considerd a top notch writer. Hemingway, Bukowski Mark Twain, Sinclair Lewis had far more interesting things to say about the American scene.

But On The Road is a good young adult novel, and should be read.

I believe the “American scene” is a concept that can only be redefined every generation. For example you mentioned Twain and Hemingway, who wrote in different centuries. Times changed significantly between their writings.

‘On The Road’ turbo charged my teens, it lent a new perspective to life that has stayed with me for better or for worse, enlightenment from a western perspective, freedom of the soul. I travelled for over 6 years and won’t ever stop, on and off. It’s a wonderful world.

Of all Ginsberg’s (admittedly uneven) opus, Howl is the piece I like for its coherence, its narrative drive and its concreteness. It takes immense skill to write something that gives the impression of being stream of consciousness. When I first read it at 15, I had no idea of its relationships to the historical body of poetry, and yet I completely understood it. OK, admittedly later I had to go back and completely understand it all over again, but I suspect that’s more an adverse comment on me than the poem.

Howl is a threshold leap – you can attempt to look back after you’ve read it, but you’re fucked.

Howl, eh?

I don’t care about “poetry” any more than I care about “television” or “films”. I mean really, who gives a fuck? Until, of course, someone writes down words, in some way, that meets you between the eyes, and changes you.

Yes. Lumberjacks are passé until… “Timber!”

Kerouac has been a favorite of mine ever since high school. I appreciated him for different reasons back then, but now I see him in a more complete, personal view. “Maggie Cassidy” is an overlooked novel that really should be read by anyone with any interest in Keroauc; I’ve never come across a more honest, poignant work about high school. I’ve been reading his letters lately (edited by Ann Charters) and they reveal so much about the daily parts of his life that may be overlooked by many readers. I’ve always hated the stereotypes attached to Kerouac; I tell people to give him more time and effort, recommending works like “Maggie Cassidy” and “Dr. Sax” so they, too, can see the depth of one of America’s greatest writers. The timelessness of his works speak for themselves, though, and, like every other author, a reader must work to find the meaning and value inherent in the words. Nice work with this article. Your thoughtful approach to these three exhibits the open, analytical attitude we should take when considering the fabric of our society and the roots it is built upon.

Fantastic stuff.

Today’s literary world is immersed in intelligent, sophisticated, polished writing (Rushdie, Saramago, etc.) that lacks any kind of vitality and, for me relevance.

There are a few truly great American writers. Guys worthy of being mentioned along side the big boys… The true giants of 20th century lit. I’m talking about people like Thomas Mann, Nabokov, Knut Hamsun, Issac Bashevis Singer, James Joyce, Celine, Durrell…the Europeans are easy.

“Blow as deep as you want to blow”

Jack Kerouac

Some of them do, literally, live on…. Gary Snyder is still alive and well and making appearances!

Brilliant post!

They were interested in Zen, and unself-consciousness – the doctrine of ‘no-mind’. Being childlike, expressing the moment, and revelling in immediacy were positive virtues.

Thanks for all the wonderful memories.

Howl has it’s moments, but I don’t think it comes together and there is far too much casual imagery in it for my liking/taste.

Surprising to learn that Kerouac was “socially conservative”, and a supporter of the Vietnam war. I have read all of the Beats mentioned above but Kerouac’s writing resonated with me more than the others. There is such a joy and wonder in his approach and I engaged with his work at the right time in my life, when I was the same as the characters in On The Road.

This is my first time hearing about the cannon! Thank you for sharing this 🙂

Kerouac was a one-off, a real original.

I agree with the point that “Howl” is is magnum opus, and that none of his other poems really pack the same punch, but I sometimes see them as little branches off of “Howl”, like further exploration of the ideas he presents in the main body.

Great analysis.

I’m reading On The Road at the moment and it is a very entertaining book

The works of the Beats is certainly still relevant and should definitely be a part of the cannon. The Beats challenged societal rules, pushed boundaries, and saw the world with fresh eyes. They reinvented and created a passion for poetry and literature alike. They started a buzz about social issues that are still quite relevant today i.e. accepting your own and other people’s sexuality. The location, a radically changing America, and history are important to reflect upon, as it was a major subject of their works. The frustration of having to follow societal rules and traditions not only in life but also in the art of writing seems suffocating. The break from conformity is refreshingly liberating and I feel that is what the Beats were about, freedom of expression.

Solid piece. It’s a nice intro to the Beats and also very well-structured and organized. I do have a few challenges for your thesis, however. Was the goal of the beats to create an ideal society, or did the Beats aim for total disengagement? Ginsberg and Kerouac alike describe individuals so disillusioned with the state of the world that they retreat into the emptiness of drugs and casual sex. You point out this theme in “Desolation Angels,” but it is also present in more subtle ways in “Howl” and “On the Road.”

Furthermore, “On the Road” is, arguably, the most popular piece of Beat literature today. I think it’s interesting that you point out that Kerouac was, in fact, the most conservative of the Beats. As I mentioned earlier, I also view “On the Road” as more of a lamentation over lost youth rather than a celebration of 1960s hippie ideals. I think this has real implications for how we view the true impact of the Beats on modern culture. Does our obsession with the somewhat cynical “On the Road” imply that we are more captivated by the Beat aesthetic than any real interest in peace, free love and all that jazz? Or, on a deeper level, does it represent the appeal of retreating into sex, drugs and rock n roll when we are politically and socially disillusioned?

Just some things to think about. You describe the main impact of the Beats as encouraging people to push boundaries in an idealistic manner, but I think some of the cynicism in Kerouac’s work complicates that.

Lastly, I know this is picky, but I wouldn’t equate Henry James and Marcel Proust. Proust is hardly formalistic — he pioneered stream-of-consciousness long before Kerouac did, and also tackled the topic of the dissillusionment of youth long before Kerouac.

Beat Movement was a protestation shout against how politics and authorities decisions made boundaries for our lives without even know what do their rules and insane conventions effect people lives and their psyches. this movement searched for great values than regular values of America. also, rebellion against boundaries of traditions. they protest against traditions interfere in the even personal life and natural passions of a human ,too like being homosexual.I think this movement pave the way for many other movements. the literature is a vociferous call for injustices and chaos of the world. they chose rebellion which way can we choose for showing our protestation against war, poverty, racism, wrong conventions, silly traditions and so on.

This article does a good job of capturing not only the central figures of the Beat generation, but the motifs and styles with which they carried their conversation on. By showing readers exactly what kind of thematic decisions they made in their craft, other writers can emulate, and progress, the work that they started back in the 1950s. Without the understanding the Beats had of the world they were living it, our modern understandings of life itself would not be as developed in such areas as sexuality, and the overall artistic drive towards life.

Great arguments presented. As much as the Beats were documenting life around them and influencing it in turn in their era, today’s alternative lifestyle is still influenced by their work and observations.

I completely agree with your thesis: “In the 21st Century, however, a reader does not need to know an iota about the sociological influences of the Beats to engage with their literature. Readers merely need to feel alienated and questioning, cynical yet romantic, searching but grounded.”

One problem was that there was a lumping together by using the term Beat. Ginsberg might be terrible to read but Kerouac could be appreciated over and over again. I remember TV shows in the early 1960s characterizing Beat, usually in sit-coms in terrible ways. Then Beat ran into Hippie and they seemed indistinguishable.

These figures seemed to gain more prominence in the 60s.