The Influence of Death on Beat Literature

The writers of what is now widely known as The Beat Generation have been both praised and criticized, loved and hated. Their works have been some of the most influential in American writing and opened an entirely new, unexplored region for future writers to occupy. While the works of each writer has clear distinctions from those of his companions, many themes are recurring in Beat literature as a whole. Because many of the writers have experienced loss and death in their personal life, this seems to be a recurring influence in their writings. Loss is not only a central theme in Beat writing but an essential part of each writer’s identity. The deaths of not only family members but mutual friends molded the Beats’ works and perspective on life, accounting for much of their carefree, spontaneous attitudes toward it. The Beats each had a personal battle with these experiences until, finally, death is greeted as an old friend, both expected and accepted.

Loss was an authoritative force in the Beats’ lives well before they became “Beats.” Each of their personal losses became an energy which transformed and metamorphosed the lives they would lead and the writings they would create. The early experience of death clearly affects each author, though in different ways. Jack Kerouac was plagued by the death of both his father and brother, forever searching for men to take their place in his life. Gregory Corso was abandoned by his mother in his first year of life and began to despise the life he could have possibly had with her. Allen Ginsberg slowly watched his mother lose her sanity until death. Each of these events was detrimental to these men and that is apparent in their writings.

Kerouac was deeply traumatized by the death of his brother. He was agonized by nightmares and was desperately afraid of sleeping alone, leading to Kerouac’s sleeping with his mother, perhaps ultimately contributed to Jack’s “mama’s boy” personality. Without a father figure, Jack spent much of his life living with his mother. Much of Jack’s life after the death of his brother was spent subconsciously searching for a replacement. This is clear in the men that become the heroes in his life and their alter egos that become the protagonists of his novels. In On the Road, Sal Paradise (Jack Kerouac’s character) idolizes Dean Moriarty (Neal Cassady’s character). Sal says of Dean, “…he reminded me of some long-lost brother…” (On the Road, Kerouac). Later in the novel, Sal repeatedly refers to Dean as his brother, insinuating there is a bond deeper than mere friendship. This is also demonstrated in The Dharma Bums’ characters of Ray and Japhy.

Kerouac also lost his father at a young age and the same characters that readers recognize as his brothers can be seen in father-figure roles at times. The character representing Jack in all of his novels is always easily influenced and taught by the other male main character, such as Japhy Ryder or Dean Moriarty. Though Sal knows his relationship with Dean is not healthy, nor will it last, he craves closeness and friendship from him. He explains, “Although my aunt warned me that he would get me in trouble, I could hear a new call and see a new horizon, and believe it at my young age; and a little bit of trouble or even Dean’s eventual rejection of me as a buddy, putting me down, as he would later, on starving sidewalks and sickbeds-what did it matter?” (On the Road, Kerouac). Because Kerouac has no male figures to look up to, he began to transform his friendships into familial relationships, and use them as a replacement for his own lost alliances. Jack had no father figure to distinguish between right and wrong and as the men he looked up to transitioned into the father role, Jack’s actions grew wilder. While Jack used the men he idolized in order to feel closer to a familiar figure, Corso’s upbringing caused him to avoid the life he could have had with his mother.

While Corso expresses nostalgia, confusion and disgust in all of his poetry, all of these works were molded by the fact that his mother abandoned him in childhood. Corso was born into a traditional Italian family, which is most apparent in his early poetry. Had he continued to live with his mother, he would have experienced traditions Italian-American families celebrate and would have felt the love of an oversized family. Because Corso never experiences these traditions, it seems he begins to despise them. This is expressed in his short but revealing poem, “Italian Extravaganza.” Corso uses this poem to express his sarcasm and confusion toward Italian traditions. The poem states,

“Mrs. Lombardi’s month-old son is dead

…

They’ve just finished having high mass for it;

They’re coming out now

…wow, such a small coffin!

And ten black cadillacs to haul it in.”

Corso’s poem clearly shows confusion as to why the death of a child should need ten black Cadillacs, something that could be seen as a sign of celebration, rather than death. While Corso first expresses sarcasm toward his roots, these feelings are soon replaced by feelings of nostalgia. The audience can feel this change in “Birthplace Revisited,” which expresses his longings toward his birth home. The poem begins

“I stand in the dark light in the dark street

and look up at my window, I was born there.”

The poem continues to explain that the place he was born is now inhabited by another family, but it has remained dirty. Both of these works by Corso were written around the same time. This establishes that his early sense of loss later lead to confusion toward his heritage. He was both bewildered and sorrowful toward the loss of his mother and the life he could have had with her, which he explored and analyzed in his writings. Though Corso dealt with the loss of his family by shunning everything that represents them in his writings, Ginsberg used the closeness he felt towards his mother before her death in order to create his poetry.

Allen Ginsberg was a witness to his mother’s loss of sanity and watched her mental and physical health decline unti her eventual death. This event was a major contribution to much of Ginsberg’s work, especially “Howl,” and “Kaddish.” Many lines of Ginsberg’s most famous work, “Howl,” recount the slow loss of Naomi Ginsberg’s mental health. He speaks of her, “Accusing the radio of hypnotism…” and explains some of the mental institutions she had spent time in. While this poem references her death, “Kaddish” was written entirely in her memory. He begins by explaining the strangeness that accompanies death:

“Strange now to think of you, gone without corsets & eyes, while I walk on the sunny pavement of Greenwhich Village…”

He continues to say that there is nothing more to say of death and that, ultimately, there is nothing to weep for. Part II explains Naomi’s long and terrifying list of experiences while institutionalized. The poem ends by sharing with the audience a letter that Ginsberg’s mother wrote to him:

“She wrote-‘The key is in the window, they key is in the sunlight at the window-I have the key-Get married Allen don’t take drugs-they key is in the bars, in the sunlight in the window.

Love,

your mother’

which is Naomi-“

This “key” is referenced several times in the poem and the poem ending with this letter suggests that Allen took these words personally, and honestly saw them as advice. While Ginsberg openly mourned the loss of his mother, his father’s death also impacted him. “Don’t Grow Old” was written by Ginsberg while mourning his father. Each Beat was familiar with death by the time they all came together in the late 1940’s. After their meeting, though, they began to experience the death of friends and colleagues, together.

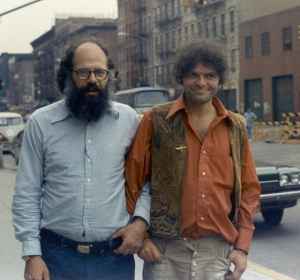

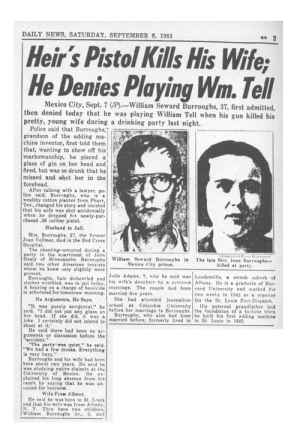

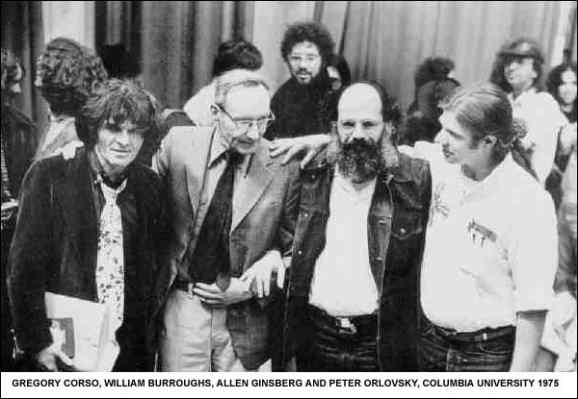

While each Beat experienced death before their infamous meeting at Columbia University, loss did not stop for the generation as their relationships and writings progressed. The writers watched their mutual friends and wives slowly be taken. The death of Joan Vollmer Burroughs was one of the first that the Beats experienced as a family. Her death clearly affected the works of the men, especially her husband and (accidental) killer, William Burroughs. Ginsberg also referenced her death in a number of his poems. Burroughs credited the beginning of his writing to Joan’s death, claiming he never would be the artist in which he became if not for the incident in which he shot her. He is noted as saying, “I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan’s death, and to a realization of the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing…So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a life long struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.” Burroughs not only expressed deep sadness at her loss but deep remorse in his own actions.

Many of Ginsberg’s poetry explored the idea of death, morality and loss. In a work known simply as “Dream Record: June 8, 1955,” Ginsberg recalled a dream which he used to analyze his own curiosity and questions concerning death. He explains,

“Then I knew

She was a dream and questioned her

–Joan, what kind of knowledge have the dead?”

The technique used here was first experimented with in “Dream Record,” and became the central technique in “Howl,” Ginsberg’s most famous work. While Joan’s death was detrimental to Burroughs’, yet constructive toward both he and Ginsberg’s writing, the death of Jack Kerouac had a more prominent effect on his fellow founders, especially Ginsberg.

The first of the Beat men to be taken by their enemy was Kerouac. This event obviously molded the writings of his friends. It is clear that these men used writing as a form of therapy. This is illustrated in the fact that many of the Beats have written poems in memory of the friends they lost. This is demonstrated in Corso’s poem, “Elegiac Feelings American,” written in Jack’s remembrance. In this work, Corso expressed his belief that Jack is the typical portrait of an all-American man. He also addressed something central to the Beats; he claims their purpose was not to find their place in America, but to speak up for its citizens, claiming,

“Was not so much our finding America as it was America finding

Its voice in us…”

Ginsberg greatly admired Kerouac, and his writings were heavily influenced not only by his death but by his writing style.

In an interview in which Ginsberg speaks on Kerouac’s work, he explained, “All of my poetic practice is founded on Kerouac’s notion of non-revising, ‘spit forth intelligence at the moment.’” He continues to discuss his works, questioning, “What does the mind really think? What is the poetry of pure mind? And [Kerouac] was the first person to have that great breakthrough of consciousness in art. Well, not the first, it is a tradition.” Kerouac’s heavy influence on Ginsberg is apparent in his writing. The audience can see the transformation of Ginsberg’s work as it becomes more and more honest after the death of Kerouac. Though death molds the writings of all these men, it eventually becomes something each Beat must accept and become comfortable with.

While it is evident in the works of Kerouac, Corso and Ginsberg that death is a terrible experience, their later writings show that death is something that one must learn to accept. Jack Kerouac claims in an interview, “…we’re all going to die.” Ginsberg speaks both of others’ deaths and of his own as something that should not be mourned. In “Kaddish,” he proclaimed,

“There, rest. No more suffering for you. I know where you’ve gone, it’s good.”

In this line, he is explaining to his deceased mother that she no longer has to suffer. In this aspect, death is positive; it ceases suffering. He also claimed that he knows where she is going after death and reassures her that it is a good place. This line demonstrates that Ginsberg has come to accept his mother’s death and is optimistic about the afterlife. In “Death and Fame,” he discussed his views for his own funeral. He begins the poem by telling the audience,

“When I die

I don’t care what happens to my body”

This demonstrates Ginsberg’s belief that the body and spirit are two separate entities. The poem continues with Ginsberg sharing what he believed others would say about him after death. The end of the poem expressed his desire for people to not only praise his work, but to praise poems such as “Kaddish,” and “Father Death” because they brought comfort to the reader. Kerouac also writes in You’re a Genius All the Time: Belief and Technique in Modern Prose that a necessity in life is to, “Accept loss forever.” This shows that Kerouac finally came to terms with the death of his brother and accepted this as loss. These works established that the Beat writers had become familiar with death. Many would even argue that Kerouac and Burroughs were welcoming death with their drug habits, which ultimately killed them.

The Beat authors were huge influences on future writers and made it acceptable and comfortable to openly express sometimes frowned-upon personal opinions. These authors made it known that we are not alone, we are creative, and we can speak out. While all of these men held their own personal philosophies and beliefs, many of them use the same ideas and experiences in order to convey them. Loss and death are a common theme among these men’s work. Each of the authors had experienced loss in the “pre-Beat” era, and they continued to experience it throughout their lives. The men who marked a generation watched each other lose their hand to Death until it became something that was expected and eventually, accepted.

Works Cited

Corso, Gregory. “Birthplace Revisted.” Mindfield. New York: Thunder’s Mouth, 1989. N. pag. Print.

Corso, Gregory. “Elegiac Feelings American.” Mindfield. New York: Thunder’s Mouth, 1989. N. pag. Print.

Corso, Gregory. “Italian Extravaganza.” Mindfield. New York: Thunder’s Mouth, 1989. N. pag. Print.

Ginsberg, Allen. “Death and Fame.” Collected Poems, 1947-1997. New York: HarperCollins, 2006. N. pag. Print.

Ginsberg, Allen. “Dream Record: June 8, 1955.” Collected Poems, 1947-1997. New York: HarperCollins, 2006. N. pag. Print.

Ginsberg, Allen. “Father Death.” Collected Poems, 1947-1997. New York: HarperCollins, 2006. N. pag. Print.

Ginsberg, Allen. Howl, and Other Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket hop, 1956. Print.

Ginsberg, Allen. “Howl.” Collected Poems, 1947-1997. New York: HarperCollins, 2006. N. pag. Print.

Ginsberg, Allen. “Kaddish.” Collected Poems: 1947-1997. New York: Harper Collins, 2006. N. pag. Print.

Kerouac, Jack. The Dharma Bums. New York: Penguin, 2006. Print.

Kerouac, Jack. On the Road. New York: Viking, 1997. Print.

Kerouac, Jack. You’re a Genius All the Time: Belief and Technique for Modern Prose. San Francisco: Chronicle, 2009. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Excellent treatise of the Beat Generation!

Thank you so much for reading! I’m glad you enjoyed the article. I love the Beats, this is my second piece on them!

my favorite writers !! i wanted to be the female version of jack kerouac,and i lived my life like he did,although i paid a huge price for it.

Yes, poor, troubled, misunderstood Jack. How can any teenage girl reading his novels not fall in love with him? At least that’s what happened for me! Thanks for reading!

This is brillant. I love the beat! Ever since I first read On the Road and Howl. This a marvelous examination of how death influenced some of the greatest writers in history.

Thank you so much. Yes, Ginsberg and Kerouac are easily my favorites. I also have another article on here essentially detailing the culture and politics of the ’50s, how it was conducive for their type of writing and their eventual influence on the ’60s and ’70s, if you’re interested!

I like how beats related to today. It gives me some inspiration for my paper that I’m writing about the beat generation. Bravo.

I’m glad I could help! I have an article on here about the Beats influence on future decades, if you’re interested.

Quite an intriguing article for someone like myself who is not familiar with the Beat generation. The motif of loss must make for poignant reading.

Easily one my favorite literary movements. Most people are introduced to them through On the Road, or another of Kerouac’s novels but I also love Ginsberg’s poetry.

good

Thank you.

I think something that contributed pretty heavily to the general theme of death within beat literature is the insularity of the movement. Like how Neal Cassady’s death could be seen in the writings of many of his contemporaries.

Oh, absolutely. Ginsberg and Kerouac’s works were especially influenced by Cassady, even being referenced in Howl. You see this over and over as the Beats slowly pass away, as well.

Also, great article! 🙂 Sorry I didn’t mention that in the first comment.

The Beat generation assisted in the freedom to publish uncensored for later generations. Despite the gritty ugliness often depicted in Beat writing, a spiritual yearning often based on the teachings of Eastern religions, Catholicism, and Judaism appeared in various Beat literary works. Both non-conformist attitudes and non-traditional writing styles are touchstones in the Beat movement.

Definitely. I talk about a lot of these points in another article I’ve written here on the site. Ginsberg’s work especially can be defined with this spiritual yearning, and On the Road rings for me when I hear that as well.

I like this essay!

Thank you for reading, I’m glad you enjoyed it!

when i left Florida for the last time, they were having a memorial in Jack Kerouacs fav tavern in St Petersburg….there were over 300 people that night…this was Nov 2011…

Amazing. I’m in love with Jack.

That was great!

Thanks for reading!

There’s something about the three major beats. They all had thier own particular motif in their works. Allen’s work is very different from Jack’s which is very different from William’s. They’re all very separate in their identities.

Very well written piece. I too am fascinated by the subculture of the Beats, particularly Ginsberg and how his life circumstances affected his style of writing. I think each of these movement members interpreted this incredible sense of loss in different ways, creating a captivating group of artists and writers.

Absolutely. Ginsberg is easily one of my favourite of the Beats,and i love that you can see his writing morphing as he grows older.

Brittany,

Thank you for the excellent piece on how you establish the influence of death with the Beat writers. I learned a lot of information from your article. Great work I appreciate it.

Thank you very much.

the heroin generation…they snapped alot cause thats about all the body functions they had left.

I don’t know about the heroin generation. They all had a different drug of choice.

Strong thesis. Much gratitude.

Thanks for the read, i’m glad you enjoyed it.

The beat movement is a detriment to American history. Truly sad..

I have to disagree. They opened the doors for many future writers, and we wouldn’t have much of the amazing literature we have today if not for them.

For anyone obsessed with the Beat Generation, like me, this is a great piece.

Thanks, I’m glad you enjoyed it. I’ve written another article on here about the Bears, if you’re interested.

Kerouac is one of my favourite authors of all time. But I must admit I don’t care for everything he does.

I absolutely love Kerouac. I agree, though. What’s your favorite of his works?

Nice work Brittany. Strong analysis and easy-to-follow writing style that are perfect for people like me who are strangers to this interesting genre. Thanks for sharing!

Excellent work and one of my favorite genres/authors. You’ve caught onto something that drew me into Beat literature in the first place. Thanks for sharing!

I found your survey of these Beat authors in terms of their relationship with loss quite insightful. This article provides a useful introduction to a topic that could be explored much more deeply for each of the authors you mention. Although your focus was on the loss of loved ones and companions through death, it seems to me that the motif could find equal application with the notion of a loss of home or place, as well as the loss of consciousness.

I was glad to see your treatment of Ginsberg included not just KADDISH and Ginsberg’s loss of his mother, but his relationship to the loss of his father as well. Are you familiar with “Father Death Blues?” It provided the soundtrack to the recent HOWL film starring James Franco, but Ginsberg seems to have composed it as part of the cycle of poems that include “Don’t Grow Old.” You can watch and listen to him perform this with his squeeze-box on the BBC’s Face-to-Face with Jeremy Isaacs. The Allen Ginsberg project provides liner notes and a link to the video: http://ginsbergblog.blogspot.com/2011/11/bbc-face-to-face-interview-1994-asv21.html.

Regarding KADDISH, Tony Trigilio published a much-cited article back in the late ’90s that advances a post-structuralist view of Ginsberg’s Tibetan Buddhism as being pre-figured in his pseudo-elegy for his mother. You may be interested in Ginzy’s “On Cremation of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche,” insofar as this poem seems to figure into his explicit Buddhist practices. Moreover, in thinking about Ginsberg’s confrontations with death specifically, you might examine his various poems for Neal Cassidy — particularly those after Neal’s death. I’m thinking of “On Neal’s Ashes” and “Elegy of Neal Cassidy,” as well.

However much KADDISH might serve as a marker in Ginsberg’s career, though, it’s important to see that he never fully resolved the loss of his mother — or, to put it another way, that he never in fact “lost” her and the bittersweet, now-joyous-now-traumatic psychic impact she had on him, as evidenced by the much later poem “Black Shroud.” In fact, Ginsberg later published Kaddish alongside the poems White Shroud and Black Shroud on the Arion Press Imprint back in 1992; that volume is out of print, but if you can find one, it seems as though it will fetch $600.00!

In consideration of Ginsberg’s relation to the loss of his own life, it might be useful to consider the sense of loss experienced by his partner, Peter, and those closest to him. One of the most interesting pieces of cinema I’ve ever had the pleasure to watch is Jonas Mekas’ video piece “Scenes from Allen’s Last Three Days on Earth as a Spirit (April 1997).” Mekas has made this project available for free on his website, along with other artifacts. It’s the fourth film in the collection on the following page: http://jonasmekas.com/online_materials/.

Finally, I wanted to suggest that Ginsberg not only sought guidance from the Hebrew and Tibetan Buddhist traditions in coping with the suffering associated with loss of life (his own and others). You can see this not only in his references to the Blues tradition early on in Kaddish, but the subtle allusions to the Homeric tradition in his emphasis of Ray Charles’ blindness. Likewise, that poem draws the reader into relation with Percy Shelley’s “Adonais,” itself an elegy for John Keats, as well as Emily Dickinson, whose poems famously treat of death as well. In the poems from Ginsberg’s oeuvre that grieve his father more specifically, we see references to Wordsworth’s “Intimations of Immortality.”

But even prior to these instances of personal loss, it seems that Ginsberg had a fascination with death and the question of what is lost when an individual loses life or another person, which seems part and parcel of the problem of how to live a happy or good life. We see this clearly in the consideration and rejection of alternate modes of life in “Stanzas Written at Night In Radio City,” and Ginsberg explicitly figures Walt Whitman as a kind of Virgilian guide through the hell of “A Supermarket in California,” which ultimately ends with a paradoxical vision of Charon piloting his boat on the river Lethe.

This, Ginsberg and the other Beats not only aspired to respond to their contemporary situation, inspection of their multifarious sources shows that they sought out models (and components of models) not just from the world’s religions, West and East, but saw themselves as working within the literary tradition that included Dante, Ovid, Virgil and Homer.

I liked the article!

I was just wondering if you chose to focus mainly on Corso, Kerouac, and Ginsberg because you are more familiar with them, or because you like them better perhaps? I often feel like William S Burroughs gets lost in the discussion of the Beat Generation sometimes. I know you included a bit about him in your article, but the William Tell routine run afoul seems like it would fit in really well with your article. Anyways, I’m certainly biased because Mr. Burroughs is my favorite beatnik.

Cheers!

Actually, I love what I’ve read of Burroughs, but in all honesty I’m much more familiar with the other Beats. He is definitely one of the Beats who is often forgot about, which is sad, but will continue as Kerouac (definitely the most popular) and the others are simply more-known.