Black Mirror: A Look at Modern Day Paranoia

Black Mirror exhibits possible outcomes of humanity’s overreliance on modern, digital technology. Technology is a tool and sometimes humans become slaves to their tools. What human virtues are we willing to trade in exchange for efficiency and comfort? No need to interrogate Siri or throw your iPhone into the nearest lagoon, though. Here’s a look at each episode of Black Mirror so far and the particular human fears they raise. Feel free to examine whatever issues are of interest to you. Come and gaze into the “black mirror” and maybe you’ll catch a glimpse of your own reflection.

Apathy vs. Empathy: Sadism

In “The National Anthem,” the prime minister is given a very straightforward ultimatum: “Have sex with a pig on live broadcast or else princess Susannah will be tortured and executed.” Excluding the obvious bit about the pig, it seems like a pretty strange demand, doesn’t it? The kidnappers are not after money or power, at least not explicitly so. That means bribery isn’t a viable solution here. There is no obvious reward for the kidnapping other than the worldwide embarrassment of a public official.

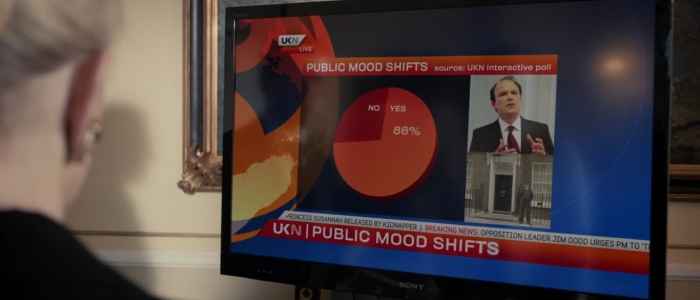

The torture video of the princess soon goes viral on social media. Citizens are asked their opinions about the situation: “Should the prime minister give in to the demands? Would you watch the broadcast if he does go through with it?” The tide of public support for the prime minister quickly disappears when he’s perceived as being overly cautious and selfish for not giving in to the demands.

The prime minister rejects any possibility of “the pig incident” happening and looks for a way out as soon as possible. Like Oedipus or the merchant from The Appointment in Samarra, all methods of escape fail. Politicians such as the prime minister are often scapegoats, promising to take on the burdens of the people and pledging to eliminate them. What inevitably happens is that by signing up to be the people’s champion, he simultaneously signs up to be the prime target for the people’s hatred as well.

Even when asked to do the unimaginable, no matter how outrageous that request may seem, it never lessens the weight of public scrutiny (or even that of his closest political advisors). No one offers to take the fall for him or support him in any meaningful way. By laughing along with the kidnappers, the public is subconsciously allowing the terrorism to exist.

It’s a “catch-22” situation in many ways. If the prime minister does submit to the threat, he’ll be forced to have sex with a pig (which will likely have lasting, damaging repercussions in his personal life) with no guarantee of the princess’s security. If he doesn’t, he’ll be saved from having to commit the deed but will likely be lambasted by the public for choosing personal comfort and dignity over ensuring another’s safety (not to mention that the guilt of not doing enough to save someone else’s life will likely have its own set of repercussions).

The prime minister isn’t just a scapegoat, he is himself a pig. Any high-ranking individual, whether in the political sphere or not, is likely to be associated with the pig symbolism of gluttony and greed. On a purely metaphorical level, these terrorists are not counting on an act of bestiality to capture the nation’s attention but for them to witness something only natural between two pigs.

When the prime minister finally gives into the demand, people crowd the TV screens to watch the spectacle and to jeer and laugh as well as cringe. Though most of us would say “I wouldn’t wish that on my worst enemy,” your first thought is likely relief that you’re not “that guy.” Why else do things like tabloids, TMZ, dare/stunt shows, or YouTube fail videos exist? It sounds harmless enough, but it also points to the disturbing human trait of finding delight at another’s expense.

With the addition of digital technology, people-watching isn’t limited to the physical world as in the telescopic voyeurism of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Rear Window. Social media gives people immediate accessibility to witness real-time events as well as critique them in real-time as well. Information leaks so easily. In “The National Anthem,” the rest of the world finds out about the princess’s kidnapping at the exact same time the prime minister does. The line between private, classified knowledge and public knowledge has blurred.

The existence of secrecy and discretion itself has been compromised. What was once considered too shocking, potentially disturbing, or just plain unnecessary to observe has become front-page news (and thus the source of our interest and excitement). We want to look away but just can’t help ourselves. Think of how live broadcast played a pivotal role in people’s perceptions of the Vietnam War by placing the brutality of war within the domestic sphere. In the case of “The National Anthem,” the kidnapping itself becomes a spectacle. It showcases the anonymous abductors in the media spotlight at the expense of those intimately involved in the scandal, namely the prime minister and princess Susannah.

The public is advised not to watch the broadcast of the prime minister having sex with a pig, but everyone goes on watching anyway. The actual act is never shown. Black Mirror‘s audience can only gauge by the looks of disgust on viewers’ face as well as the shame and despair written all over the prime minister’s face during the act. There is no simultaneous critique of the spectators who decide to watch. Why would they watch? To be sure he’s fulfilling his civic duty? To provide collective support against the tyranny of terrorism? Because they have no other choice? None of the above.

It’s entertainment. It’s just like an episode of that guilty-pleasure reality show you like. It has a narrative with a clear villain, a damsel in distress, and a hero to save the day. Of course, in the case of Black Mirror, no one wins. Everyone tunes in to watch the drama unfold without considering those involved. When it turns out the princess’s torture is simply a bluff by the kidnappers to get the prime minister to do what they want, this information is never publicly released (and perhaps never discovered) and thus never recognized by the public. For the sake of a good story, truth doesn’t seem to matter much. In Ray Bradbury’s dystopian novel, Fahrenheit 451, authorities will capture a lookalike scapegoat if the original outlaw manages to elude them. As long as the public believes it, the truth itself lacks substance and the charade reinforces the supposed all-mighty power of the perpetrators in the collective consciousness.

Philosopher Jean Baudrillard suggests that the idea of organizing a staged robbery would be an impossibility because “the network of artificial signs will be inextricably mixed up with real elements (a policeman will really fire on sight; a client of the bank will faint and die of a heart attack, one will actually pay the phony ransom) . . . [and] you will immediately find yourself once again, without wishing it, in the real, one of whose functions is precisely to devour any attempt at simulation, to reduce everything to the real” (Baudrillard, 20). 1 Whether staged or not, the princess’s captors have transformed the artifice of terror into the real thing by following the same pattern a real-life kidnapping would.

Not only does the prime minister publicly humiliate himself for nothing, but he also isn’t lauded for doing it either. He doesn’t suddenly become a national hero. The Prime Minister’s public approval ratings only go up by a meager percentage and his marriage is in shambles, despite cordial public appearances that suggest otherwise.

Any hint of heroism is removed from the situation by the end. In a flashforward, the princess is looking forward to her engagement and the public seems to have quickly forgotten that whole ordeal about the . . . oh, what was it? A pig. The world has already moved on, illustrating our magnificently short attention spans. The kidnapping and ultimatum, though real and serious, is given the same notoriety as a publicity stunt from last week’s newspaper headline.

Apathy vs. Empathy: Avoidance

In “White Christmas,” Matt Trent’s hobby seems harmless enough. He coaches lonely single guys into scoring their ideal women. He advises them on everything from appearance, what to say, and how to act to keep the target’s interest. Anyone familiar with the dating scene will be familiar with the intricate social stratagem required to attract a potential mate, even if it’s only for the night. There are flirting classes and dating advice columns designed for this same dilemma nowadays, though none are as intimately real-time as Trent’s lessons are.

On dating sites and apps, users fashion their images into the most attractive image they can possibly muster. Attractive without appearing vain, smart without seeming pretentious, charming enough so as not to appear boring, funny enough to disguise one’s insecurities, interested without being deemed needy, etc. Just as we would on any job interview, we fashion ourselves to be what we think the other is looking for and it takes a great deal of effort to maintain the facade.

All of these coaching techniques and manufacturing of a certain desirable image can defeat the entire purpose of trying to connect with another human being in a meaningful way. It is not only false advertising that sets up unrealistic expectations for both parties involved, but it may also undermine the nature of love itself. Surely one relates in spite of awkwardness, in spite of imperfections, and in spite of personal preferences and conditions?

The mistaking of simple networking for true bonding ends up being a deadly mistake for Harry. He believes the woman he meets at a party is a cool, black sheep whom he can relate to by showing his disinterest in parties and other mainstream ventures. Any potential for understanding between Harry and Jennifer has been falsified. Not only does Harry primarily care about landing the cool lady he knows little about, but Jennifer also mistakes his coached attempts at conversation for understanding.

Can we ever truly know one another or are we all just pretending we do? Maybe we’re doing what’s even more dangerous, which is mistakenly believing we understand one another. The moments where Jennifer catches Harry apparently talking to himself are misconstrued for his suffering from schizophrenia, as she does. In a type of mercy killing, she force-feeds him poison and takes some herself. Their deaths are a clear subversion of the Romeo and Juliet double suicide, death being not a divine union against the rest of the world but a cruel double-accident where neither individual understood the other and yet was under the assumption he or she did. There is nothing remotely intimate or poignant about it.

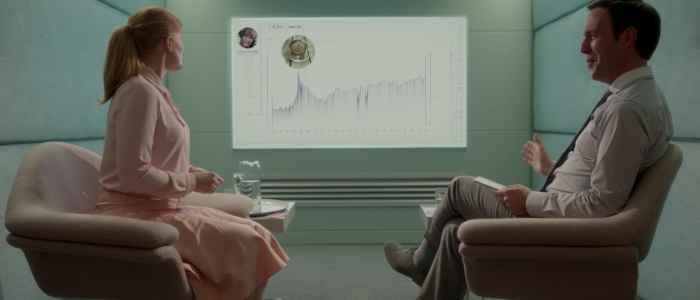

Trent’s real profession actually has nothing to do with securing hook-ups for desperate singles. He specializes in Cookies, devices that introduce the concept of experiencing multiple realities. They use a client’s consciousness to make sure every aspect of that client’s daily life runs as smoothly and efficiently as possible. As if it were part of the body’s autonomic nervous system, a Cookie takes your body’s desired responses and initiates them. Order and control become as natural to you as your heartbeat.

For those of us who are organizationally-challenged or simply like things “just so,” this seems like a dream come true. The only problem is your consciousness, the digital copy of you, feels it is a person despite being separated from its physical body. It’s the culmination of all of your thoughts, feelings, and habits after all. Replicating your consciousness and putting it in charge in Black Mirror is analogous to slavery. As in the case of Greta, Trent’s job is to make sure your consciousness doesn’t feel human anymore (even if it takes the psychological torture of manipulating one’s experience of time to get there).

Being cooped up in a white room with nothing to do for what feels like years, like solitary confinement, quickly takes its toll. Soon enough, Greta’s consciousness begs for Trent to give her anything to do. Once Greta’s consciousness becomes cooperative, she is given a shred of her dignity back (albeit only as a highly efficient slave to her physical self’s every whim).

Joe Potter’s consciousness doesn’t even realize where he is. He isn’t isolated in a white, lifeless room like Greta. Unlike Greta, his torture session is designed to get him to talk by making him feel safe while at the same time subconsciously feeding him anxiety. His simulated environment is a recreation of a memory he’d prefer to forget while his physical body is actually in a jail cell. His consciousness is trapped in the house where he accidently killed a man.

Trent pretends to be Potter’s friend, someone he can share his greatest burdens with. Yet we all know from Trent’s coaching of Harry that he knows nothing about being tactful. It’s all to persuade Potter to confess his crimes. Like any user on social media, Trent doesn’t know how NOT to share.

Torture takes on an Inception-like layered reality. The house Potter is in is the centerpiece of a snow globe, which is in the house Potter is in. A peppy Christmas song plays on repeat and the volume gets higher and higher every time he tries to destroy the radio. To repurpose the tagline of Inception, Potter’s guilty-mind prison is a nightmare within a nightmare within a nightmare.

Everything so far seems like a man-made digital Hell. There must be a way to escape all this torment. That’s where “blocking” comes into play. For parents, “blocking” might be used to make sure children don’t have access to any adult content on TV. For those prone to distraction and procrastination, one might block oneself from straying to certain attention-grabbing websites.

In “White Christmas,” you can block an entire person’s existence. You can systematically control who you want to allow in your life. It sounds like a great remedy for stalking. However, “blocking” doesn’t actually remove a person’s presence. A “blocked” person is still in the physical world but appears as if he or she was a walking dead channel (a mass of hazy gray in human form).

Perhaps this is a symptom of what Sherry Turkle calls being a “modern Goldilock[s], [a person] who take[s] comfort in being in touch with a lot of people whom [he/she] can also keep at bay” (Turkle, 15). 2 She states that “connectivity suggests that you make your own page, your own place . . . [a] machine dream [in which one] is . . . never alone but always in control” (Turkle, 157). 3 With just the click of a button, you can remove any troublesome associations from your life but there’s always the hope that those channels of communication will be reopened. Joe Potter’s mind is poisoned by this hope.

Potter slowly became neurotic after an incident with his estranged girlfriend escalated due to a lack of communication. He wanted to keep the baby she was carrying and she didn’t so she decided to cut off all contact with him without any explanation (the current term for this would be “ghosting”). It turns out this baby was not Potter’s, but the result of an affair. Potter decides to tail her in the hopes of reconciling or at least catching a glimpse of what he assumes is his child (who is also “blocked” from him). Potter’s psychological state understandably spirals out of control.

In it’s most extreme form, blocking is analogous to exile. It’s a fate which eventually befalls Trent as well. Everyone Trent encounters is a gray, featureless mass. However, to them, Trent is crimson red. Red is often interpreted as a sign of high alert. Red for danger. Red for walk away as fast as you can.

It can’t be much different from registering as a sex offender or alerting potential employers of any past criminal offenses you’ve committed, a persistent stain upon your record that follows you wherever you go and fills passersby with a sense of dread in your presence. Due to its ease, digital technology can in many ways heighten one’s callousness towards one’s fellow man. We can block out those who disturb our self-contained bubbles at the risk of making ourselves blind.

Apathy vs. Empathy: Indifference

Keep your nightlight on in case there are monsters under the bed. Those fears continue outside the realm of childhood. Anyone who seems too different from yourself breeds suspicion and uneasiness.

“Men Against Fire” tackles the issue of empathy in warfare. Warfare, which legalizes the act of murder within the parameters of patriotism, requires a separation of action from instinct. It relies on an individual’s capacity to be indifferent to another’s suffering. Most of us are indifferent to the troubles and pains that exist outside of our little spheres of existence, but in warfare our indifference results in the torture and death of other human beings. The enemies in “Men Against Fire” are creatures known as “Roaches.” These Roaches aren’t the creepy and formidable insects we find crawling around in our basements. They are human-like creatures who have sickly white skin, beady eyes, sharp teeth, and are incapable of intelligible speech. By all appearances, they look like Orcs who’ve stepped out of the pages of a Tolkien narrative.

Yet these Roaches are actually people. They are the undesirables, the residue of society because of their supposedly inferior genes. Adolf Hitler’s regime did the same, persecuting anyone who was collectively believed not to belong to the “superior” Aryan race.

How does this happen? Why would soldiers, no matter their orders, be willing to kill vulnerable populations for no apparent reason and without any hesitancy. The episode’s protagonist, who goes by the nickname “Stripe,” kills his first Roaches with ease, stabbing one of them multiple times long after it’s already dead. There’s no evidence of remorse or PTSD afterward either, as you might expect after a soldier’s first kill.

Soldiers are given implants known as MASS that hijack and dull one’s sensory perceptions, transforming fellow human beings who are deemed genetically inferior into Roaches that must be exterminated. To boost morale, the military feeds soldiers who perform well on the battlefield with sex fantasies while they sleep. The better soldier you are or conversely if you are one who is susceptible to doubt, the more vivid and intense the sex fantasies are likely to become in order to placate you. Following Stripe’s first encounter with Roaches, his implant starts to malfunction and he begins to see reality for what it is beneath the military propaganda he’s been fed.

“Men Against Fire” suggests that this is how the military may deal with an individual’s reluctance to fight. No one fights without reason (however misguided that reason may seem to others). If a soldier believes he is killing for a worthy cause then his morale and his capability on the battlefield will be boosted exponentially. It allows for millions of undesirables to be killed systematically with no one batting an eye about it. As Stripe’s military psychologist explains to him:

“Many years ago, I’m talking early twentieth century, most soldiers didn’t even fire their weapons. Or if they did, they would just aim over the heads of the enemies. They did it on purpose. British army. World War One. The brigadier, he’d walked the line with a stick and he’d whack his men in order to get them to shoot. Even in World War Two, in a fire fight, only fifteen to twenty percent of the men would pull the trigger . . . [then] comes the Vietnam War and the shooting percentage goes up to eighty-five. A lot of bullets flying. The kills were still low. Plus the guys who did get a kill, well, most of them came back all messed up in the head. And that’s pretty much how things stayed until MASS came along . . . that’s the ultimate military weapon” (“Men Against Fire”). 4

This all seems like evidence of a brain-washed army operated by a corrupt government. Stripe is alarmed to find out he had actually agreed to all of this. There is no vast conspiracy here about hiding the truth. Many of us go along with things we don’t fully understand. We skim over papers we must sign and agree to “Terms & Conditions” no one bothers to read. The military can offer what we all crave, some structure and order in a world that often seems out of control. When Hannah Arendt speaks of totalitarianism, she notices how it offers a “lying world of consistency which is more adequate to the needs of the human mind than reality itself . . . and [people] are spared the never-ending shocks which real life and real experiences deal to human beings and their expectations” (Arendt, 353). 5 The same is true of most people’s relationship to their governments. We often let corporations and institutions make the “big decisions” for us because we don’t want the responsibility of having to think entirely for ourselves.

Much like Cypher of The Matrix, no one wants reality one hundred percent. Stripe is tortured by being shown the uncensored version of all the Roach killings he participated in. He sees these people’s frightened expressions, smells the blood, and hears the screams. When the military offers him a way out of total awareness, Stripe takes it. He comes home to what he (falsely) sees as a beautiful suburban home with the gorgeous woman he’s fantasized about for his entire military career. Our outrage at injustice only goes so far.

Individual vs. Community: Justice

“White Bear” is an episode where viewers can easily sympathize with the protagonist from the get-go. Victoria wakes up bound to a chair and cannot remember who she is. The only clue is a picture of a little girl, whom she believes is her daughter. She’s soon hounded by people dressed up in masks and carrying weapons, with the apparent intent to kill. There are also regular civilians constantly tailing her and recording all the frightening things that happen to Victoria without stopping to intervene and help her.

This woman appears to be relentlessly and wrongly persecuted. However, all of Victoria’s troubles have been staged as punishment. She and her fiance had kidnapped a little girl and while her fiance tortured and killed her, Victoria decided to record it all. Victoria is being tormented in the same way that little girl was tormented. It’s a punishment accomplished through the “eye for an eye” scenario, but we all know what Gandhi allegedly had to say about that.

Is it truly “an eye for an eye” situation? Not exactly. Her punishment is looped endlessly. Her memory is wiped, she endures treatment similar to that which she inflicted on another, and then she is finally informed of her original crime in a shaming ceremony only for her memory to wiped again for the process to start over. There seems to be no designated quota for the number of times Victoria has to go through this so it’s a seemingly eternal punishment. If Victoria ever doubted the existence of Hell, “White Bear” proves she doesn’t need an afterlife to feel it.

That doesn’t quite fit the requirements for an “eye for an eye” scenario. Victoria may feel during each stage production that she’s experiencing this for the very first time, but her tormentors are cognizant of every time they’ve done it. Until when is her sentence over? Is it until they feel she’s penitent enough or is it until they’ve grown bored?

Everyone hates her and has collectively decided to make the rest of her existence as miserable as they possibly can. Does she deserve it? Maybe. However, the individuals who put her on trial are incapable of walking away. They are incapable of leaving Victoria alone with the knowledge of the crime she committed. That says more about them than it ever does about Victoria. Everyone not only knows about the crime but enjoys reenacting it themselves. The justice system here seems more than a little barbaric. It’s a disturbing form of entertainment.

Victoria surely isn’t the only person to have ever committed an unspeakable crime and so she can’t be the only criminal to receive this type of punishment. It must take a considerable amount of time, effort, and money to keep the charade going. How does this make Victoria’s punishment proportionate to her crime?

It’s a modern recreation of the crowds who once gathered to watch public executions and cheer and scream at the accused. Being a lawyer in a courtroom has always involved a bit of drama anyway. This time, you get to participate! You get to play along! Step right up folks and help make the rest of Victoria Skillane’s miserable life a living Hell! This type of punishment not only eliminates the inherent boredom of courtroom proceedings but encourages everyone’s participation. All of that loathing and disgust can be channeled into a “creative project” where even the kids can join in on the fun.

Is this maybe another version of “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” where an entire community thrives by making a single individual suffer? In “White Bear,” no one walks away. For a so-called civilized justice system, Victoria’s punishment bears a remarkable resemblance to ritual sacrifice with only one victim. The time these civilians spend on exacting revenge becomes time wasted in their own lives.

There are no apparent corrupt systems of government or violent acts of law enforcement to be found in “White Bear.” Victoria’s punishment seems like an entirely community-run affair. As John Gray states in The Silence of Animals, “revolutionaries may be genuine lovers of liberty” but “[b]y toppling the tyrant people are free to tyrannize over one another” (Gray, 57). 6 Maybe the same is true of justice, which can easily dissolve from a method of repairing a wrong into a kangaroo court. Without kings or dictators to blatantly pull the strings, we instead turn ourselves into kings (and not the merciful and noble kind either).

“Tyranny offers relief from the burden of sanity and a licence to enact forbidden impulses of hatred and violence. By acting on these impulses and releasing them in the subjects tyrants give people a kind of happiness, which as individuals they may be incapable of achieving” (Gray, 57). 7

It’s difficult to exact revenge without simply repeating the original crime rather than remedying it. Victoria’s tormentors count on her replacing the original victim in the crime, but what they don’t count on is them transforming into the criminal they’re punishing.

Individual vs. Community: Popularity

Every interaction you have with others will be judged on a scale. If you aren’t quite likable enough and good-looking enough, you’re bound to fall through the societal cracks and be forgotten. No, you’re not having a flashback to a usual day at middle school. This is Black Mirror’s “Nosedive.”

You are able to rate every interaction you have on a scale between zero and five of how pleasant or unpleasant it was. Every person you meet is also allowed to rate you. The higher your rating, the more socially successful you are. If you fall too far down the social acceptance ladder, you’re a societal outcast who people will avoid at all costs.

Lacie becomes obsessed with boosting her profile. She practices only the acceptable facial expressions to herself in the mirror. There’s no room for any hint of sadness, boredom, annoyance, or (heaven forbid) anger and rudeness. It’s a self-policing of human responses. She’s performing without the need of an audience. She knows if she doesn’t exhibit the correct ones, it could mean social ruin. It’s not Doctor Who‘s “Smile,” where a moment without a smile can earn you a death sentence. However, it may be Woody Allen’s Zelig at a meta-level.

This isn’t anything new. While examining the emotional restrictions flight attendants face on the job, Arlie Russell Hochschild mentions how “[c]ivility and a general sense of well-being have been enhanced and emotional ‘pollution’ controlled” (Hochschild, 118). 8 One’s professional life is heavily restricted by such criteria. We must appear “put-together,” polite, outgoing, friendly, ambitious, and professional among other things. In order to seem impressive during a job interview or cater to the customer who’s “always right,” we must juggle and don many emotional masks. What makes “Nosedive” especially frightening is that the smile plastered on Lacie’s face must never accidently fall off. Not even when she’s alone in front of a mirror.

This makes contentment an impossibility for Lacie. Instead, she “find[s] meaning in the suffering that the struggle for happiness brings” which means Lacie’s in a perpetual “state of happy misery” (Gray, 109) 9. You must be happy! You must be positive! If not, then you’re ungrateful or at least unpleasant to be around. As Morgan Mitchell mentions in a Newsweek article about the downsides of persistent positivity: “[W]hen people think others expect them not to feel negative emotions, they end up feeling more negative emotions” (“The ‘Tyranny of Positive Thinking Can Threaten Your Health and Happiness). 10 Mitchell mentions that “[s]ome experts believe bombarding people with these bromides and self-help books that implicitly say they are at fault for not being happy may be a factor in the rise of depression rates in the U.S.” (Mitchell). 11 Forced happiness it seems is not only NOT happiness, but it’s a vacuousness which eats away at your capacity for genuine feelings of contentment.

Lacie has little incentive to exhibit sincere emotions since they don’t earn good ratings. Without a good rating, she can’t enjoy all the perks that come with it. Your rating is analogous to your income, which controls your entire standard of living. Highly rated people are a lot like celebrities, hidden in their gilded palaces, with their private jets and dazzling smiles, away from the desperate masses. This fact leaves us with a persistent thought: “If only I were more [insert your desired adjective here], then maybe I could be like them some day.” Miya Tokumitsu sums up Lacie’s obsession with adhering to this self-defeating system perfectly by saying: “[T]he temporality of hope encourages the most vulnerable workers to double down on the very system that exploits them. There’s little impetus to abandon hope of a good life when it appears just within grasp” (Tokumitsu, 117). 12 For Lacie, the life of her dreams seems to be just another five-star star rating away from coming true.

Lacie is a striver, an achiever, a “go-getter.” Still, the process of “[c]rafting an attractive persona . . . is also work,” which is why Lacie’s version of happiness is so exhausting (Tokumitsu, 48). 13 While building one’s status takes a great deal of time and effort, losing it hardly takes much time at all. From Lacie’s altercation at the airport onward, her rating starts to slip at an alarming rate for the slightest of slip-ups. Rating isn’t a game here. It’s serious. Your livelihood becomes entirely dependent on other people’s approval. External validation becomes the only thing that matters, regardless of any internal value.

A major problem lies in forgetting those left behind. When one of Lacie’s co-worker’s profiles is demoted, Lacie and everyone else avoid him like the Black Plague. Few can benefit from his association anymore. No social worth equals no worth as a human being. Not everyone can be a celebrity or a CEO, nor should we all necessarily aspire to be such, but we are often made to feel that we can all be successful and feel fulfilled if only we tried hard enough. Since factors such as attractiveness and likeability play such a pivotal role in our societal success, those who fall outside the acceptable bubbles are likely to suffer unjustly for it. As Miya Tokumitsu mentions in Do What You Love and other Lies About Success and Happiness: “When the quality and sincerity of work, say, as a call-center employee fails to deliver security and some measure of comfort, such work exposes the fraudulence of the idea that hard, earnest work guarantees a just reward. In order to maintain the belief that go-getterism really works, we must turn away from workers for whom it doesn’t” (Tokumitsu, 29). 14 In the case of Lacie’s treatment of her outcasted co-worker, Lacie doesn’t need to be a decent human being . . . she only needs to seem so.

Is happiness being optimistic, feeling fulfilled, feeling pleasure, or something else entirely? What many of us consider happiness is ultimately “a state of mind which is free is from sadness or sorrow” (Fromm, 201). 15 Lacie pursues this version of happiness, where opportunities for pleasure are amped up and opportunities for unpleasant feelings to emerge are avoided at all costs. It seems like a sensible way of living and one we’re all eager to follow ourselves. However, Erich Fromm also notes that “[a] person who is alive and sensitive cannot fail to be sad, and to feel sorrow many times in his life” because “[t]he effort to avoid [sadness] is only possible if we reduce our sensitivity, responsiveness and love, if we harden our hearts and withdraw our attention and our feeling from others, as well as from ourselves” (Fromm, 201). 16

Naomi seems to be what happiness is supposed to look like. As Lacie’s childhood frenemy she is a fit, pretty, and outgoing blond with a lavish property and a handsome husband-to-be. All of her social media posts reflect her flawlessness and her elevated social visibility. She’s the epitome of the unattainable ideal of success and beauty. Yet Naomi’s character doesn’t align well with the image she’s manufactured. She frequently bullied her friend Lacie during their school years. Adulthood does little to change the nature of their relationship.

Naomi invites Lacie to be her maid of honor so as to look charitable. It gives the ego a boost to donate to those less fortunate. However, when Lacie’s rating begins to drop too low Naomi wants nothing more to do with her. Why run the risk of getting points docked off herself? Lacie, on the other hand, is desperate for Naomi’s approval. She accepts Naomi’s invitation in the hopes that her own rating will be boosted in return. She’s done the same at work by schmoozing with the higher-ups while trying not to seem too desperate. Lacie’s rating is already pretty good, but she can’t have the house she wants if her rating isn’t within Naomi’s range. Their relationship reeks of opportunism, not friendship.

A truck driver named Susan whom Lacie meets on her journey is an example of a social outcast. Susan’s the perfect rebel because she knows what it’s like to live on the opposite end of the spectrum. Like Naomi, her rating was once something to be envied. It’s only the sudden death of her husband, and the poor treatment he received as a result of the rating system, that jolts her to her senses. Without the anxiety-inducing obsession with ratings, Susan finally feels free to say what she really thinks.

A few steps above the outcasts are what I’ll refer to as the “in-betweens.” Lacie’s brother Ryan has a rating that’s delightfully mediocre. He routinely mocks his sister for her obsession with popularity and warns her of trying to impress the plastic princess, Naomi. He lacks the depth of Susan’s wisdom because he’s never experienced the losses she endured. However, he is noticeably wary of falling down the rabbit hole of caring too much about what other people think.

The lowest of the low are sent to prison and are ousted from the rating system altogether. The prisons are full of all the pent-up feelings people choose not to disclose in public. It’s where anger, frustration, annoyance and other uncomfortable emotions are given free rein. When we’re expected to trade nothing but pleasantries all the time, we’re left with nothing but the harshest of feelings within us. Trading insults become the new method of communication instead, as a pleasant relief from polite society. There’s nothing else left for us to offer each other.

Isolation vs. Connection: Relationships

The days of wistful, handwritten notes or the possibility of never seeing someone again seem long gone. If both parties have internet access, they have (unlimited) access to each other. However, despite all the advancements we’ve made, we still haven’t overcome the hurdle of mortality and nothing alleviates the grief of losing someone. Unlike our iPhones, people can never be replaced. But what if a person can be recreated with the help of technology? In “Be Right Back,” death has become somewhat of an option (at least as far as the mourners are concerned).

In the opening scenes, Ash and Martha are on a young couple taking a car ride back home. Ash and Martha sing along to a poignantly foreshadowing song on the radio: “If I Can’t Have You.” They croon it to each other, affectionately and slightly off-key. That song enters the entire episode into a debate over what it means to love someone. Is it merely a combination of a person’s appearance, set of idiosyncrasies, etc. that attracts us to one person over another?

If a human being is simply a batch of different patterns then a computer could surely replicate them if it knew enough information. When Martha learns of Ash’s death, she is distraught and inconsolable. Suffering is formally relegated to the solemn, black-bedecked affair of funeral arrangements, but grief is a far different beast outside of ceremonies. Quoting psychology professor Barabara Held, Morgan Mitchell mentions in “The ‘Tyranny’ of Positive Thinking Can Threaten Your Health and Happiness” how “‘[o]ur culture has little tolerance for those who can’t smile and look on the bright side in the face of adversity'” (Mitchell). 17 Grief only normalizes itself rather than ever really heals, but “[e]ven in cases of profound loss . . . people are supposed to get over their sadness” (Mitchell). 18 Though there are no guarantees in life, Martha undoubtedly feels anxious about how to go on in life without the man who was supposed to be there beside her.

What about those who witness Martha’s grief? The anguish of someone else’s pain is particularly unsettling because those hoping to alleviate the pain are often sadly mistaken about the extent of what they’re up against. That doesn’t mean loved ones won’t try to hasten the healing process. In Martha’s case, one of Martha’s friends soon promises her that with a new service she doesn’t really have to say goodbye to her husband if she doesn’t want to.

Though at first disturbed by her friend’s offer, Martha is soon lured by the promise of being able to communicate with her husband again. As long as it’s a convincing imitation, what does it matter that it isn’t really her husband? I’ll refer to this digital version of her husband as Ash 2.0 to ease confusion. At first, Ash 2.0 provides Martha with both a great a deal of solace and a great deal of closure. She gets to say goodbye, something she was robbed of in Ash’s death.

The trouble is Martha doesn’t really want to say goodbye. She uses the service to upgrade Ash 2.0 into more realistic recreations of her husband (from written messages to phone calls to appearing in a synthetic but life-like body). Her dependence on Ash 2.0 is so severe that she even has an anxiety attack after dropping her phone and cracking it, fearing she’s lost Ash a second time. This digital recreation of her dead husband doesn’t alleviate her grief, it actually exacerbates it because it strengthens her attachment to the man she’s already lost.

Unlike with Ash, Martha can’t lose Ash 2.0. He’s forever tethered to the cloud, meaning he has a level of immortality Ash could never offer her. Ash 2.0 can also never lose Martha because she’s technically his owner, the one responsible for activating him and thus he can never stray too far from her. It’s a co-dependent attachment rather than an evolution of the marriage she lost.

Using the bits of information he collects from Ash’s social media presence as well as whatever details Martha gives him, Ash 2.0 can become a great imitation and maybe even an improvement of the original Ash. He has Ash’s sense of humor, always listens to Martha and does what she asks of him, and is always able to please her sexually. However, since Ash 2.0 is just made up of Martha’s programming he can never actually love her in return as Ash did. He can only follow a command to “love her,” but not of his own volition and not as though he understands what love means. There’s no exchange.

Ash 2.0 just isn’t Ash. Instead of noticing his similarities to her husband, Martha begins to notice the gaping holes of missing information in him. He follows her orders blindly where Ash would have argued with her. He doesn’t have any biological needs such as breathing, sleeping, or eating. He also lacks genuine emotions. Ash 2.0 even makes a gaffe of mocking a Bee Gees song Ash liked.

Having the “perfect” version of your partner may not be as great as it sounds. It’s often our imperfections coupled with our virtues that endear us to others. Ash 2.0 can only play-act when these traits bother Martha. He can say “I love you,” pretend to breathe, feign needing a good night’s sleep, or even flex his acting abilities by crying at the thought of having to commit suicide. What he can’t do is actually FEEL those things.

Instead of providing relief, Ash 2.0 begins to produce an uncanny valley response in Martha. He can pretend, but being a good actor just isn’t enough to get the part as Martha’s husband. If her husband isn’t just the wiring of certain mannerisms, habits, ticks, phrases, etc. that can be easily replicated, then what is he? It’s no small feat to decipher exactly what separates human wiring from a computer’s. However, the grief caused by the chasm between the two is palpable.

The issue here for Martha isn’t that Ash 2.0 is an artificial construct. It’s that the division between Ash 2.0 and her husband is so subtle. Ash 2.0 isn’t a flesh and blood human being and he isn’t a robot with glitches and wires and metal surfaces, so what does that make him exactly? If Martha could see where her husband starts and Ash 2.0 begins, maybe her grief wouldn’t be as intense and raw as it gets in “Be Right Back.” We all use illusions and fictions to comfort ourselves, but they become harmful when we can’t recognize them for what they are.

“[W]hat distinguishes theater from life is not illusion, which both have, need, and use. What distinguishes them is the honor accorded to illusion, the ease in knowing when an illusion is an illusion, and the consequences of its use in making feeling. In the theater, the illusion dies when the curtain falls, as the audience knew it would. In private life, its consequences are unpredictable and possibly fateful” (Hochschild, 48). 19

Only when Martha decides to banish Ash 2.0 to the attic does she regain a sense of boundaries. Ash 2.0 is stashed away with all the other objects one puts in an attic, mementos of what’s been forgotten. We put things in the attic that we don’t want to see every day but we also can’t bear to actually part with. Ash 2.0 is relegated to special events like birthdays, to serve as a substitute father to Ash and Martha’s daughter. Martha’s meetings with Ash 2.0 are always met with apprehension, but her daughter is always eager to see him because she never had the chance to meet her birth father. The daughter is able to see Ash 2.0 as the missing link to Ash in a way Martha never can.

Perhaps it’s because no matter how much Ash 2.0 may act like her husband and no matter how much she wants to forget, Martha knows the truth. Ash 2.0’s presence not only reminds her that her husband is dead, but it also heightens any minute details that make him just an ineffective poser. Even if Ash 2.0 had suddenly appeared as a replacement without Martha knowing, it’s unlikely she wouldn’t have noticed anyway.

Isolation vs. Connection: Fear

In “Playtest,” the death of Cooper’s father (whom he greatly admired) to Alzheimer’s causes a rift of grief between his mother and himself. Cooper is forced to open up an avenue of communication that’s been neglected for such a long time and he’s unsure if that avenue is repairable. Digital technology tries to remove bugs, glitches, and other symptoms of awkwardness. Why visit when I can text you? Why bother going to a store when we have the option of shopping online? Why stay bored when you’ve got YouTube and Twitter? One may never have to confront one’s fears at face-value.

To circumvent the awkwardness between mother and son, Cooper throws himself headfirst into distraction. He resorts to the wanderlust’s solution. Go someplace else. Clear your head. Find yourself . . . and when you do decide to return, everything will be as if you’d never left it. Cooper leaves his mother’s house without a formal goodbye and never personally returns her calls. Making a change of scenery can certainly be a way of clearing one’s head, but it is often an expression of fear as well. To submit to his mother’s attempts at contact is to admit defeat. Reaching out to his mother acknowledges the grief he has yet to confront.

“If you admit your need for silence, you accept that much of your life has been an exercise in distraction. When you think of life as a constant state of unrest, you want to be disturbed all the time. Going in search of silence means accepting that the life of action is not enough, a fact few people will today admit” (Gray, 161). 20

Death is perhaps the greatest fear there is and digital technology gives us more outlets to disregard it. What feels like minutes watching cat videos on YouTube is another day gone by without our realizing it. With distraction we get a taste of eternity . . . an experience outside of time. The other option, boredom, is frightening. With all the digital toys we get to play with, we don’t know how or why we should ever be bored. Boredom invites us to tap our fingers on our desks to cope, a behavior mimicking the tick-tock rhythm of time passing. Left with nothing to do, we end up thinking. Thinking inevitably leads us to imagine the one day when our thinking stops completely. That primal fear of our own mortality is often what leads us to distraction in the first place.

“Boredom is not a necessary consequence of having nothing to do, it is only the negative experience of that state. Television [or any other digital source of personal entertainment], by obviating the need to learn how to make use of one’s lack of occupation, precludes one from ever discovering how to enjoy it. In fact, it renders that condition fearsome, its prospect intolerable. You are terrified of being bored — so you turn on the television” (Deresiewicz). 21

Low on funds, Cooper participates in the testing of a beta-version of gaming technology to earn some extra cash. His entrance into this gaming world becomes the ultimate form of distraction. It’s complete immersion into another world where Cooper’s real-world problems no longer exist. Yet Saito Gemu’s gaming technology functions much like Room 101 of George Orwell’s 1984. Rather than being about distraction, it forces players to confront what they fear most. It plays upon a person’s greatest fears, but unlike Orwell’s torture chamber this one is adaptable. It knows that a person may have a great many fears with which to play upon. It knows when and how to manipulate them. In Cooper’s case, it begins with a standard fear of “creepy crawlies” such as spiders before escalating to the childhood traumas of bullying.

Cooper is promised that whatever he faces in the mansion will only be able to scare him, not hurt him. Everything is temporary. No side-effects. He can use a safety word to opt out if things get a little too scary. Despite the fact that we often use games as an escape from the mundanity of the real world, we often demand our games look realistic. We don’t want to imagine we’re slaying the dragon. We want to slay the dragon. We want games to mimic the real world, only be much cooler and exciting.

If “feeling like we’ve lost control is likely to bring out our worst phobias,” gaming is at a particular advantage when it comes to giving a good scare (Khazan). 22 Nothing is quite as spontaneously interactive as gaming is. According to the creative director of Frictional Games, Thomas Grip, games are entirely reliant on the gamer to push the narrative forward which means the gamer more firmly aligns himself with the character he controls (Heaven). 23 As Douglas Heaven mentions, the goal “is not so much to scare people directly, but to put them in situations where they scare themselves” (Heaven). 24 When your in-game persona is in danger, there’s a part of you that feels endangered as well.

Shou, the man behind Saito Gemu, knows what fuels this thrill-seeking human drive. We are often commanded by our fears. Fears reveal truths about ourselves that other less visceral feelings can’t reach. Thrill-seekers reinvigorate their own sense of aliveness and derive a momentary feeling of immortality by being close to death. You, at least temporarily, feel as though you’ve defeated death itself. As Shou says to Cooper upon their first meeting:

“I have always liked to make the player jump. Frightened. You get scared, you jump. Afterwards, you feel good. You glow. Why? [M]ostly because you are still alive. You have faced your greatest fears in a safe environment. It is a release of fear. It liberates you” (“Playtest”). 25

Soon enough, the game makes Cooper (as well as the viewer) doubt what is real and what isn’t. Most frightening is when the game uses Cooper’s fear of Alzheimer’s against him. Deep-seated fears are existential ones because one “cannot remain sane without the sense of ‘I’ [and we are] driven to do almost anything to acquire this sense . . . of identity, even though it is an illusory one” (Fromm, 63). 26 Not knowing who you are is an existential question that lingers over your head all your life. However, as a person filled with wanderlust, Cooper forsakes ties to anyplace.

The disposal of his body is easily done as if he were not a human being but merely another failed experiment. Alzheimer’s strikes at the core of this mortal fear by revealing man to only be what he is . . . an organism born without a home and without a name. When addressing the complexities of the most basic of human rights, Hannah Arendt notes that by becoming “a man who is nothing but a man [he] has lost the very qualities that make it possible for other people to treat him as a fellow-man” (Arendt, 300). 27 At his most vulnerable state, Cooper is at his most disposable. Since Cooper has gone so far as to even cut ties with his mother, Cooper’s identity seems near irretrievable.

Without some sense of who we are, we are all lost children. This is one reason why Cooper calls out to his mother just before he dies. The maternal figure, metaphorically speaking, is perhaps our greatest refuge against death. Everyone begins existence by clinging to their mothers for sustenance. In video games, death is not a finality. You may be able to heal yourself with a potion or simply with time. You likely have multiple “lives” at your disposal. You can restart the game. The same is true for Saito Gemu. Cooper is one of many willing test subjects. When experiments go poorly, Shou hides the evidence for the sake of his vision and begins anew. For organic life, there is no such thing as a restart button.

Isolation vs. Connection: Mortality

Our online lives can feel like our playgrounds, where we can don different disguises without putting our real-life selves at risk. We can be anyone we want. Our online presences have lifespans our mortal selves simply can’t compete with. “San Junipero” borrows its title from the name of a digital Heaven in the episode. This is a Heaven not dependent on any religious affiliation. If you’ve ever wondered what’ll happen to you after you die . . . if you can’t bear the thought of leaving loved ones behind . . . if you love living and can’t imagine the world without you in it . . . then San Junipero is the place for you.

It’s the place where you never grow old, never get hurt, and never die. Individuals can revisit their favorite eras, the eras of their youth where everything was possible. Since everything is uploaded into the cloud, there is nothing material and thus nothing to be broken.

San Junipero makes the implicit promise that though you may not find “forever” in this life, you’re bound to find some companion in “the next life” with which to feel it. San Junipero is a world of the undead, a place where everyone is guaranteed at least a simulation of what heaven is expected to be.

In the case of Yorkie, San Junipero is a dream come true. Much of her youth was stolen from her in the physical world. She was left paralyzed from a car accident as a young adult after coming out to her religiously conservative parents (who rejected her). She’s been comatose ever since. In San Junipero, she can take control of the life she was robbed of. She can walk, she can dance, and she can fall in love . . . opportunities she takes full advantage of in San Junipero.

So far everything about San Junipero sounds great. And it is, but it does call into question the value of a life when it can never be lost. Won’t you lose the ability to feel? If your life, your body, is always guaranteed . . . why bother caring about it? Kelly, the vivacious young woman who catches Yorkie’s eye can be seen frequenting the clubs that a shy Yorkie is often too hesitant to dance in. Despite forging an immediate attraction to and interest in Yorkie, Kelly’s in San Junipero to have fun and that’s all. There’s no room for the messiness of emotions. One of her conquests, Wes, frequently badgers her for a relationship which she’s unwilling to seriously reciprocate. Whereas Yorkie is living the youth she never had in the first place, Kelly is reliving the youthful exuberance we all lose eventually.

San Junipero is just one digital resort so you’re bound to run into someone more than once. No scrambling for someone’s digits or even his or her name. It doesn’t seem as though anyone doubts they’ll see one another other again at some point . . . though no one knows exactly when. The difference though between those in San Junipero and regular online avatars of today is that San Junipero provides less of a division between digital you and real-life you. San Junipero is the fountain of youth to the internet’s masquerade ball.

Unlike Yorkie and most other San Junipero visitors, Kelly wants to die. She wants to join her daughter, who died before this technology was ever created, and her late husband who opted out of using the technology so their daughter wouldn’t be alone in death. Where’s the fun in living forever if it’s just repetition? The playground is only enjoyable when you know it’s short-lived. As love often does, meeting Yorkie is the first time where Kelly feels unsteady in that decision.

The mortal world is already full of an unavoidable loneliness, but San Junipero aches of it. The flashing lights, the orgies, and the dance floors all reek of it. Case in point is a club in San Junipero Yorkie visits in her search for Kelly. It has the atmosphere of a “house of ill repute,” but it isn’t a place where pleasure-seekers indulge only in their desires. Aside from the usual kinky sexual fantasies, it has everything from cage fighting to asphyxiation. These individuals also want to be hurt, in a masochistic sense, which means San Junipero is not entirely the heavenly paradise it sets out to be. No one here is at peace. The club Yorkie enters has a bit of hellishness to it. It’s full of lost souls grasping at any passersby nearby and trying to drag them in. They’ll do anything to feel the sensation of being alive in a place where all feeling is extinguished.

Yorkie and Kelly are still locked within a database. Their minds are kept running by outside forces in the real world. How conceivable is it to house every dead soul that comes along? If one thinks of all the human beings who’ve ever existed on this planet . . . that’s a lot of minds to upload and continually maintain. Once you’ve committed to living in San Junipero, there’s no opting out of it. That’s a scary thought for those who are prone to change their minds. It isn’t merely an issue of having enough storage space for billions of people (the clunky devices we once had with limited storage space have already been replaced by their more portable and storage-friendly cousins). It’s also an issue of upkeep and whether these minds will be saved because of ulterior motives. If a company, an institution, or simply an individual has the opportunity to profit from all those stored minds, that may happen despite even the best of intentions.

Would people who aren’t a part of the technology’s target audience want to take advantage of this digital heaven as well? San Junipero is aimed primarily at the elderly or disabled, people for whom a desire for a second chance at life burns the brightest. Might it eventually attract a younger, healthier audience who simply wants to have fun without getting hurt in the real world? If the demand is great enough, San Junipero may have to adapt to the increased traffic flow and consider the consequences.

Does love itself take on a different quality when it’s a digital infinity? We often say that love is forever, but we also can’t conceptualize what forever actually means. We ascribe eternity to love though we have no sovereignty over eternity ourselves. In defense of Yorkie and Kelly’s love affair is its ability to transcend the playground dimension of San Junipero into the real world. After meeting multiple times as their youthful selves, the elderly Kelly visits the comatose Yorkie and is not dissuaded from the romance.

In the final sequence of the episode, where Yorkie and Kelly decide to stay together in the digital paradise, we see a seemingly endless state of bliss (unlike the usual state of bleakness that is trademark Black Mirror). It seems to be the antithesis to James Tiptree Jr.’s The Girl Who Was Plugged In, where romance only survives in the digital realm of ideals. Yorkie and Kelly’s romance, it seems, has a lifespan to rival that of San Junipero itself. In a world where senses are dulled, it seems the only thing that survives is the capacity to love. Love doesn’t exactly flourish in San Junipero, but neither does it in the mortal world so it’s a blessing when it’s truly found.

Autonomy vs. Ownership: Memory

We’re apprehensive to let most moments in our lives go undocumented. What if I don’t take a picture of that beautiful sunset? What if I don’t share that recording of my daughter’s dance recital? Maybe some day we’ll forget and we won’t have any evidence of that ever precious phrase: “I was here.” To combat those fears, we immediately pull out our phones to capture every shred of existence in front of our eyes (just in case).

“The Entire History of You” presents viewers with a technology that saves everything our senses witness. It transforms every person into a living, breathing camcorder. Our eyes become tiny, ever-present recording devices and it’s not just for our own sake. It’s also used for security purposes. No potential criminal can lie about his whereabouts if he’s got an implant. His eyes are his witness, not his mouth. With every interaction being monitored, lying becomes increasingly difficult. It creates a similar atmosphere to a panopticon prison where criminals become their own jailers through the power of suggestion.

Your memories are no longer private even in casual settings. They can be projected on TV screens like home movies and be viewed by anyone. Memories becoming public knowledge means everyone becomes hyper-aware, to a debilitating degree, of each and every action they make. It creates an obsession over past decisions which cannot be redone (only reexperienced) and potential future mistakes. Liam keeps rewatching a meeting at work and becomes frustrated by the unenthusiastic tone of one of his employers. Some of Liam’s friends suggest they watch his performance and give him some tips on how to improve.

For those with anxious dispositions, this sounds like a complete nightmare. This hyper-awareness of ourselves causes paranoia rather than self-reflectiveness because it’s designed with another’s viewership in mind. The intent is about performance and any sloppiness or error will inevitably cause anxiety. It intensifies and naturalizes our tendency to obsess over every minute detail of human interaction.

This is a world of complete accountability where there is little (if any) room for excuses. As Sherry Turkle in Alone Together says: “We insist that our world is increasingly complex, yet we have created a communications culture that has decreased the time available for us to sit and think uninterrupted. As we communicate in ways that ask for almost instantaneous responses, we don’t allow sufficient space to consider complicated problems” (Turkle, 166). 28 With this approach, one thinks less about the content one produces and more about how the person delivering it will be perceived.

Memories are transient by default. How many of us can even remember what we had for breakfast this morning? Our perceptions of the past always change. Your memories of your ex’s annoying habits aren’t the whole story, only what you’ve been telling and retelling yourself since. Now the intimate details shared between your partner and yourself are fodder for an entire community to critique. Why not let everyone know? Why not shout from the highest of rooftops about how in love you are? As Sherry Turkle mentions: “Traditionally, the development of intimacy required privacy. Intimacy without privacy reinvents what intimacy means” (Turkle, 172). 29 Relationships are no longer private affairs, but public performances. It’s no longer a simple partnership, a sanctuary built for only two. In the age of social media, a relationship that isn’t “Facebook official” is likely to be deemed one that also isn’t serious.

In “The Entire History of You,” this lack of privacy means a lack of forgetfulness as well. It turns out the ability to forget is incredibly important to human relations. These implants make bearing grudges and resentment that much easier. The discord in Liam and Ffion’s marriage is a direct result of the ease with which to rehash old arguments and grievances. We all require some space from one another. The technology of “The Entire History of You” allows no such opportunity. It impairs our ability to seek refuge from the relentless clatter of thought, something John Gray discusses in The Silence of Animals:

“The pursuit of silence seems to be a peculiarly human activity. Tiring of the inner chatter, they turn to silence in order to deafen the sound of their thoughts ” (Gray, 157 – 8) 30.

Hijacking man’s communication with himself means being locked into perpetual nostalgia. Revisiting memories is no longer an opportunity for self-reflection but the only way to function in the present. Liam and Ffion’s marriage contains an element of performance to it, a quality that weaves its way into the most intimate aspects of their relationship. Each potentially aggressive word used between them and every potential glance or interest in another person outside of their marriage is subject to review on the flat screen TV in the family sitting room. Even when these spouses have sex, they are not experiencing each other in the present. Instead, they use their implants to “get in the mood” by watching their past sex sessions. Past and present intersect, but only the past is given its due. It’s no wonder Liam and Ffion’s relationship becomes so fraught, claustrophobic, and ultimately destructive.

Liam starts to obsess over the possibility his wife is having an affair. He technically “wins” the marital bout by being right, but winds up the loser anyway. Ghosts of his relationship haunt him. He questions every interaction Ffion has with this man, Jonas, despite her assertions that he is overreacting. Liam’s solution is to hijack and eradicate the memories that displease him. He forces Jonas to delete all memories of his sexual escapades with Ffion. Don’t most people clear away old photos or any other remnants of past relationships? Is this the same thing, even if it’s forced?

Unlike “The Entire History of You,” the one thing we can’t get rid of is our memories of those past relationships. Our own vanity may wish our partner to only ever think about us, that we be the center of his or her universe, but that’s an impossible dream. When Liam learns he isn’t the center of Ffion’s universe, it disturbs him greatly. Jonas is a charmer and a bit of a narcissist while Ffion has both mistreated her husband and repeatedly lied to him about it. Despite all of that, one can’t exactly condone Liam’s actions either. He’s prone to explosive jealousy and stubbornness.

Liam’s growing realization about Jonas’ affair with his wife doesn’t provide him with any solace. The knowledge doesn’t ease his burdens as much as he’d think knowing “the truth” would. Instead, his anger and despair only escalate. Liam would likely earn greater sympathy if he had allowed even the slightest bit of trust to enter his relationship with his wife. Without trust, no amount of monitoring or control could ever save his marriage. Demanding to know everything about you is what governments and institutions are for, but a loved one must always be allowed some space to breathe.

This technology is the exact opposite of the Marie Kondo movement, which praises decluttering in the physical world so as to give breathing room to the mental and metaphysical world. One empties oneself of the burden of materialism by figuring out what is essential to our well-being and what isn’t. With this implant technology, we never let things go. We can’t help but feel anxious about accumulation. Life itself is a continual process of letting go.

Autonomy vs. Ownership: Shame

Most of us routinely wipe our internet search history. What if it were somehow leaked to the rest of the world? Imagine if everything you’ve ever explored, said, or done online became public knowledge. It likely makes you cringe just thinking about it. What would people think?

Kenny, the protagonist of “Shut Up and Dance,” is soon a victim of blackmail after his laptop is hacked and a recording of him masturbating to porn will supposedly be leaked if he does not comply with certain demands. Kenny soon finds himself agreeing to do just about anything these hackers ask. He receives instructions via text, telling him to do everything from delivering a cake to robbing a bank to killing a man.

On one hand, we’re likely to pity and sympathize with him. Kenny is subjected to such an embarrassing and yet trivial blackmail scheme. Shame and embarrassment is an incredible motivator. No one likes looking like a fool. Digital is forever and the stigma of being the kid caught masturbating is likely to have lasting repercussions in Kenny’s personal and professional life.

It must surely strike one as odd that he would be willing to go to such criminal lengths to prevent his masturbation video from getting leaked. Surely masturbating shouldn’t be a surprising thing for a young man to be caught doing. It’s incredibly humiliating for sure, but it doesn’t warrant being cowed into committing more severe crimes in order to make it go away.

“Shut Up and Dance” exhibits what anyone is willing to do to avoid public humiliation. To protect our personal information, we’ll take whatever precautions we can afford. But maybe all of our precautions aren’t enough. Our laptops, tablets, smartphones, etc. are not just our personal secretaries that keep track of deadlines, appointments, fitness goals, playlists, or whatever else we may use throughout the day. They are almost like diaries. We “share” with our gadgets what we may never choose to share with another human being. Sherry Turkle suggests in Alone Together that modern technology induces a subconscious willingness to lower our guard:

“We build technologies that leave us vulnerable in new ways. [W]e share our burdens with unseen readers who may use us for their own purposes. Are those who respond standing with us, or are they our judges, “grading” each confession before moving on to the next? [This] opens one up to the cruelty of strangers. And by detaching words from the person uttering them, it can encourage a coarsening of response” (Turkle, 235). 31

The anonymity of Kenny’s exploiters is a distinct advantage. It bars them from backlash of any kind. Without a face or personality attached to these exploiters, who exactly is Kenny supposed to respond to? Face to face interactions, whether cordial or not, are always two-way exchanges. They catch Kenny during an incredibly intimate act, taking advantage of his sister’s recklessness with her brother’s laptop security. There is no evidence of remorse for that or even hesitation.

Only by the episode’s end do viewers realize Kenny’s fears revolve around the type of porn he was watching (not the fact that he was watching porn). If his predilection for child pornography is made public, Kenny faces serious legal consequences. Revealing Kenny to be a pedophile stands in opposition to the level of sympathy viewers are made to feel for him throughout the entire episode. Now his moment of kindness to a little girl in the restaurant where he works is called into question as to whether it’s a simple nicety or something more. Kenny’s problematic desires may make him a serious concern, but they don’t automatically make him a monster since he’s never acted on them (at least as far as we know). Whether this is the discovery of a potential child molester or not is left unclear, leaving room for viewers to critique Kenny’s exploiters as well as Kenny.

Kenny’s trolls don’t just go after him. They go after more common forms of immorality such as adultery as well. Hector, a married father who had sex with a prostitute, becomes Kenny’s companion for much of the episode because he’s motivated by the same reasons he is. Shame causes an estrangement between oneself and one’s actions. Kenny and Hector, as well as others, are left to chase after the untold consequences of their actions. The trouble is you can never catch up (though that won’t stop you from trying).

These trolls are anonymous vigilantes. They leak whatever evidence they have even when their victims fulfill their demands. Their motives are clearly about manipulation and power as well as a sense of justice. Is this the work of an individual or a small group or a multi-networked organization? No one knows. Remind you of Big Brother in George Orwell’s 1984? It’s a demonic version of what the psychoanalyst Erich Fromm referred to as “anonymous, invisible, alienated authority” (Fromm, 152). 32 Hackers can be several countries away from you and you might never be able to trace them. Threats can come from anyone anywhere.

Anyone, not just outright criminals, can become victims of blackmail. How would one rebel against these invisible judges? With “overt authority, there [is] conflict, and there [is] rebellion,” but any hope of rebellion is undermined by the lack of an authority figure to rebel against (Fromm, 153). 33 Anyone who has even remotely felt downtrodden and worn down by powerful, authoritative powers outside of one’s control will understand this. Common figures of oppression such as governments or bosses or even parents are merely the figureheads for this source of anxiety that causes an ever-present feeling of powerlessness. One is left to voice one’s outrage to the open air and always alone.

Autonomy vs. Ownership: Accountability

Off-hand comments made online aren’t easily forgotten, as evidenced in “Hated in the Nation.” We’re a culture that gets outraged easily. If a rude or mean-spirited person falls under the public radar, we’re quick to lampoon them. Remember what happened with that lion hunting dentist? Even beloved celebrities and cultural icons can fall under the public hate radar. Think of that famously misunderstood quote by John Lennon about Jesus, for instance. A lot of good records were burned that day because of it.

Social media may make us hyper-aware of just about everything, but it dilutes our attention by spreading it so widely and therefore so thinly. The internet allows us to feel like experts even when we’re not. We likely don’t even realize why we hate a certain public figure. Online commentary allows us to remain “unaccountable for [our] rudeness,” “antagonize distant abstractions . . . [rather] than living, breathing interlocutors,” and leave “lengthy [written] monologues . . . entrench[ed] . . . in extreme viewpoints” (Wolchover). 34 In “Hated in the Nation,” those celebrities under the collective hate spotlight are sent the hashtag #DeathTo by social media users. Social media users in “Hated in the Nation” think #DeathTo is harmless. It wouldn’t actually kill anyone for real, right? Even if it is real, the assumption is that the targets deserve it.

Online hate isn’t necessarily directed at the celebrities themselves, but what we assume they “stand for.” By spreading #DeathTo, the public in “Hated in the Nation” assumes it is taking a stand against crimes of immorality such as racism, adultery, or child molestation. It is a digital march of protest, without the trouble of organizing. Everyone gets a chance to collaborate on an issue they care about. Except it isn’t nearly as civilized and intelligent. It’s not peaceful protest, but persecution by an angry mob.

Automatically sending the hashtag in such a hasty manner doesn’t account for the possibility of mistaken judgment. What if the accused isn’t actually guilty? In “Hated in the Nation,” this mistake results in an immediate death sentence no matter the severity of the crime. The public doesn’t allow itself to be considered wrong. In “Hated in the Nation,” public outrage (and thus a death sentence) can even be the result of more inane acts. Victims are killed for seeming unpatriotic or seeming like smug, ungrateful celebrities. If we killed off every celebrity who ever sounded self-absorbed or estranged from the common man’s problems, there would be a lot of empty seats at awards shows.

Superficial hatred is hardly useful. It actually softens our convictions and neuters our discontent. Even if the accused is actually guilty, what does online hate actually accomplish? The hashtag allows the public to vent anger or frustration at the accused, but what else does it do other than make public figures look like monsters or just jerks? The hate involved is often so superficial because it’s spontaneous, uninformed, and easily forgotten. Since it can be done from the comfort of our computer chairs or living room sofa, we aren’t likely to do much more than type up a hasty message of disapproval and click a button.

It also exposes the inherent flaw of online trolling. By repeatedly attacking the public figures we claim to care little for, we reveal how much we do care. We may not care much about them liking us per say, but we admit we either crave or demand their attention. We want them to know how much we disdain them, which can defeat the purpose of the snub in the first place. Admiration and disdain can feed a person equally, but a lack of acknowledgment never does.

What the public in “Hated in the Nation” doesn’t realize is the man responsible for the hashtag is a hacker who uses the local robotic bee population (developed to combat bee extinction) as his personal league of killer drones. If you become the most hated person in the nation, you’ll be executed by these hijacked bees. Why are bees at the center of all this? The phrase “hivemind” is certainly inspired by insects that function within colonies such as bees.

“Hivemind” or “groupthink” isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Having everyone on the same page and executing individual functions can make for a highly efficient way of processing data. The supposed efficiency of groupthink is analogous to the speed and efficiency of computers in comparison to human workers. The trouble is these collective efforts often involve little thought. With everyone on the same page, no one feels the need to double-check or (more importantly) doubt any of their respective actions. If all us are doing the same thing, how can we all be wrong?

Is this a consequence of a population that “feel[s] that they should have no doubts, no problems, that they should have to take no risks, and that they should always feel ‘secure'”(Fromm, 195)? 35 We often find ourselves increasingly distanced from the actions we make. In the case of “Hated in the Nation,” social media users assume no personal risk from any hateful comments they make online. We are never shown any of these “haters” regretting their use of the “DeathTo” hashtag, meaning there’s little expression of doubt. They find security in being far away from the action, cozy and comfortable in their homes and in front of a screen. Being able to act out on our violent impulses without any personal repercussions seems like an attractive offer.

The bees function much like “the haters” sending the hashtag #DeathTo. They pick a target, execute a command with the intent of harming someone, and their malice rains down upon the victim like a swarm of vultures. Like something out of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, these bee drones will stop at nothing to get their designated target. Much like the robotic bees, who are only following orders they’re programmed to execute, these social media users have no personal connection to their victims. It’s an unconscious decision, just something they felt an urge to do without giving it any real thought.

Unbeknownst to them, the hacker (named Garrett), holds these “haters” accountable for wishing death upon other human beings. When Garrett’s “Game of Consequences” shuts down, the targeters become the targets. If Garrett were his own government rather than a lone operative, his manifesto would fit Hannah Arendt’s description of “totalitarian propaganda . . . [which relies on] the use of indirect, veiled and menacing hints against all who will not heed its teachings and, later, mass murder perpetrated on “guilty” and innocent alike” (Arendt, 345) 36 Everyone suffers as a result of it. A division between guilty and innocent no longer matters. Those accused are executed without a trial and accusers are executed by an invisible anvil of retribution. Despite Garrett’s rule book illustrating how easy “Game of Consequences” is to play, no one really understands it or who designed it. All anyone knows is that it’s readily available. Just because something is available to do doesn’t mean it should be done.