Charlotte Turner Smith: Empowering Women with a Sonnet

When one thinks of writers who have paved the path for women in the literary scene, names such as Mary Shelley, Charlotte Bronte, or Jane Austen likely spring to mind. Another woman deserving of a place on this list is Charlotte Turner Smith. Both a poet and novelist, Smith led an intriguing life and produced fascinating and transformational works.

One such work is Elegiac Sonnets; a collection of poems published in 1784. These Sonnets are each alike in their melancholic tone, as their title suggests. An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, often a lament for the dead. Smith published several editions of Elegiac Sonnets; her preface to the sixth edition states this mood plainly:

“I wrote mournfully because I was unhappy–And I have unfortunately no reason yet, though nine years have elapsed, to change my tone.”

Scholars have identified that Smith likely suffered from depression. Given the context of her life, however, melancholia would serve as a better term. During Smith’s lifetime, melancholia was inherently linked to male artists; it was believed to be the product of high intelligence, rationality, and sensibility. This condition was perceived as necessary for good poetry. Alternatively, melancholic women were often treated as ‘hysterical’ for having the same condition. This is as women were believed to be incapable of rational thought. 1 By writing of her melancholia, Smith understood that she would be placing herself amongst the ‘celebrated’ poets who expressed the same feelings. To avoid being perceived as an hysterical and over-emotional woman, Smith wrote about her melancholia within the clearly definable Sonnet structure. It served as a way of showing control over her own negative feelings — she was not controlled by them.

This constrained unhappiness inspired thirty-three sad and intelligent poems in total, across nine published editions. Many of these poems explore the hardships she endured throughout her life. They also express her discontentment with being a disempowered woman during the eighteenth century. As this article will explore, Charlotte Turner Smith can be seen to empower eighteenth century women with her collection of Elegiac Sonnets. From the context of its publication, to the themes discussed within the poetry itself, Smith challenges patriarchal norms with her art.

Poetry as ‘Masculine’

During Smith’s lifetime, writing was perceived as an inherently masculine art. While a woman could write within the private domain — for family or friends — they were criticised when they chose to make such work public. It was thought of as ‘immodest’ for a woman to place her writing outside of the private sphere; the domain to which she supposedly belonged. To publicise was to expose oneself, leading to various sexual assumptions. 2

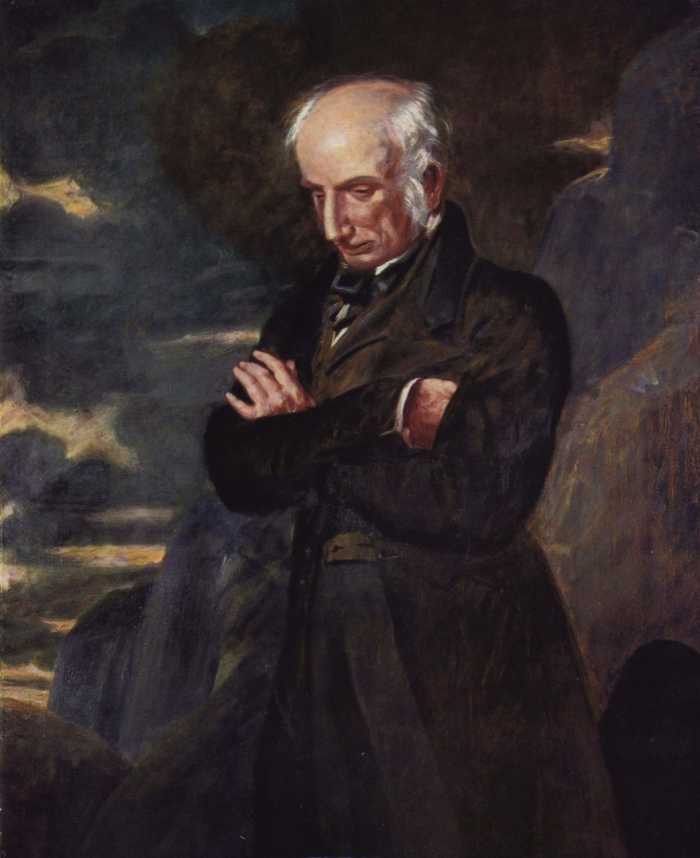

Looking to poetry more specifically, this was perceived as part of a great masculine tradition. 3 Therefore, the simple existence of Smith’s published work suggests a defiance of oppressive patriarchal norms. More than this though, she was highly influential within the literary scene. As per the masculine tradition, the Romanticism movement is almost always discussed in relation to the so-called ‘Big Six.’ These are powerhouse poets who are still highly regarded today: William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Blake, Lord Byron, Percy Shelley, and John Keats. What is often forgotten, though, is that the first two on this list were influenced by Smith. Wordsworth once stated that Smith was “a lady to whom English verse is under greater obligations than are likely to be either acknowledged or remembered.” 4

For Coleridge, Smith’s poems served as the ‘model’ from which the poet would learn the rules of the Sonnet. It is also from Elegiac Sonnets that Coleridge identified feelings of loneliness and sorrow as essential to the Sonnet form. However, Smith had a more profound impact on Wordsworth. His sister, Dorothy Wordsworth, recalls that her brother committed much of his time to reading through Smith’s poetry. 5 Wordsworth used his poetry to explore many of the same themes as Smith; including nature, the human condition, and memory. The most obvious influence, though, is in Wordsworth’s borrowing of different phrases from Smith to use in his own poetry. 6 There are several examples of this, one being Smith’s poem, ‘To Night.’ The Sonnet opens:

“I love thee, mournful, sober-suited Night!

When the faint moon, yet lingering in her wane,

And veil’d in clouds, with pale uncertain light…”

This is similar to the lines of Wordsworth’s ‘Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood.’ Lines from this poem read, “The clouds that gather round the setting sun / Do take a sober colouring from an eye.” Though it is only a small detail, Wordsworth can be seen to use the same idea of a cloudy night being ‘sober.’ As Wordsworth spent time reading her work, this similarity in description cannot be a coincidence. A range of other works by the famous poet have demonstrated this kind of copying, including ‘Tintern Abbey’ and ‘The Old Cumberland Beggar.’ 7 The two artists not only share similar themes and descriptions though, Wordsworth also uses several of the same poetic rhythms as Smith. Thus, her influence on these poets can be clearly discerned.

One way in which Smith influenced the literary tradition more generally was in the so-called revival of the English Sonnet form. Traditionally, there are two main structures of this type of poem. During the eighteenth century, the form and structure of the Italian, or Petrarchan, Sonnet was recognised and appreciated. However, the English, or Shakespearean, Sonnet was not yet a notable part of the literary tradition. Smith wrote within the confines of the English Sonnet, and it was through her use of the structure that it became increasingly popular by the end of the century. 8 For someone who society deemed inappropriate for the writing milieu, Smith’s ability to exert influence over the literary tradition would have been empowering for like-minded women at the time.

Smith’s influence becomes further significant when one looks upon her career in retrospect. Despite the fact that she was writing before the prominent Romantics, Smith can be understood as the first to have written within the conventions that modern scholars identify as Romantic. Thus, unbeknownst to herself at the time, she was a pioneer in one of the most significant literary movements to date.

Arguably, though, the most remarkable part of Smith’s writing life is the fact that she infiltrated this boys’ club in order to usurp the provider role of her husband. Due to a series of unpaid debts, Smith’s husband was imprisoned; the poet was forced to be incarcerated with him. She published Elegiac Sonnets in order to support her family and, in doing so, earned enough money to pay-off his debts and free their family. 9 In defying one patriarchal tradition by publishing poetry, she defied another in becoming her family’s provider.

Shifting the Muse

Moving beyond the mere context of the poet’s life, closer reading of Smith’s poetry reveals further sentiments of female empowerment. While Smith interjected herself into a masculine field, she did not merely write to suit the established canon. Instead, she made the art of the Sonnet her own.

Typically, Sonnets were the artworks of men, written with the “hypersexualized female form” as the muse. 10 These poems were written with a beautiful woman in mind, and the women were often compared to nature to emphasise their beauty. There is scarcely a better example than William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18, “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” However, rather than following the same tradition, objectified female beauty was not the focus of Smith’s poetry. Instead, nature was her muse.

Nature as Muse

From the beginning of Elegiac Sonnets, nature is the focus of Smith’s writing. Almost every poem is, in some way, focused on the natural world. Whether that be through addressing, describing, or embodying the world around her. Smith is playful with this idea of nature as her muse in Sonnet VIII, subtitled ‘To Spring.’

In this poem, Smith addresses the season of Spring, using a technique known as ‘apostrophe.’ This technique involves addressing an absent person, an idea, or a physical object as if it were a person, and as if they were listening. From the outset, this humanises Spring. However, due to the specific way in which Smith does this, the poem can be read as a love letter to the season.

The poem opens by describing all of the lovely things about this time of year, from the partially formed nests “of finch or woodlark,” to the flowers scattered around. The woods are “drest” in varying shades of green. However, the writer then changes the poem’s focus to make it personal. She describes the impact that the season has on her. This passage from the middle of the poem suggests as such:

“Ah! season of delight!–could aught be found

To sooth awhile the tortur’d bosom’s pain…”

Unlike the Sonnets that Smith would have been used to reading, the natural world in this poem is glorified for its physical beauty, not a woman. However, the poet also expresses an acute emotional attachment to Spring. Thus, not only has she managed to move away from depicting women as passive, she has also expressed value in the object of her affection beyond mere physical beauty. Her beloved season is able to cheer her up and soothe her emotional pain. By transforming the patriarchal Sonnet form, and making a muse out of nature, Smith’s writing is empowering for women.

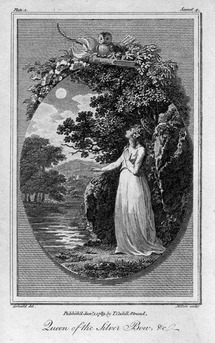

The Unobjectified Woman

Women did not simply disappear from Smith’s Sonnets, though. Instead of an objectified inspiration, the women in Elegiac Sonnets are able to express their inner thoughts. Rather than an object, Smith transforms the woman into a figure capable of emotional complexity.

Smith’s ‘Nightingale Series’ can be interpreted as a semi-autobiographical account of the suffering the poet endured. The ‘Nightingale Series’ is comprised of three poems within Elegiac Sonnets, ‘To A Nightingale,’ ‘On the Departure of the Nightingale,’ and ‘The return of the Nightingale.’ 11 To begin with, birds within poetry are popularly interpreted as symbols of poetic self-reference. When a poet writes about a bird, they are indirectly writing about themselves. The bird’s ‘song,’ then, is a reference to the very poem in which they are featured.

Doing a close reading of the first of the series, Sonnet III, or ‘To A Nightingale,’ this self-reference becomes evident. The poem opens:

“Poor melancholy bird—that all night long

Tell’st to the Moon thy tale of tender woe;

From what sad cause can such sweet sorrow flow,

And whence this mournful melody of song?”

The parallels between this bird and Smith are unmistakable. The Nightingale is sad and spends whole nights expressing such grief. This expression is described as “sweet” and melodic. Remembering that she wrote this whilst imprisoned with her husband, like the bird, Smith channelled the sadness she felt towards life into her poetry.

The connection between the two becomes more apparent as the poem continues; the poet begins to project her own pain onto the bird:

“Say—hast thou felt from friends some cruel wrong,

Or died’st thou—martyr of disastrous love?”

Smith, forced into marriage with the man who caused her imprisonment, clearly felt as though she was both wronged by friends and the martyr of a bad relationship. With her series of Nightingale poems, Smith is ditching the trend of one-dimensional muse women. In stark contrast, Smith is equally as capable of expressing complex thoughts as her male peers. This poet’s appropriation of the Sonnet form, and her alteration of the subgenre’s focus, can be interpreted as a rejection of patriarchal norms.

‘From Petrarch’

Continuing this idea of a woman in a man’s world, in several instances within the collection, Smith almost literally takes the place of a man. Four of the poems within Elegiac Sonnets are subtitled ‘From Petrarch.’ Within these Sonnets, Smith writes from the perspective of poet Francesco Petrarch; she offers her own English translations of his works. In doing so, she embodies the male poet, establishing a connection between Petrarch and herself. By taking the place of this popular male poet, Smith is arguably attempting to “melt” herself into the world and culture of male poetic tradition. 12

The poems that Smith translate all focus on the figure of the woman muse. This woman, named Laura, is the elusive object of the original poet’s unrequited love. Of course, when any text is translated, it is almost never as it was originally intended. Smith’s translations are no exception, and can be read as a criticism of Petrarch for loving an idealised, thus potentially untrue, version of a woman.

Petrarch’s Sonnet 90 and Smith’s translation in Sonnet XIV both demonstrate that the original poet is describing a memory. That memory is inaccurate, as it remembers the beloved as more than human. Petrarch’s poem reads:

“Her way of moving was no mortal thing,

but of angelic form: and her speech

rang higher than a mere human voice.”

This can be compared to the corresponding lines in Smith’s poem, speaking from the perspective of Petrarch, which similarly state:

“Thy soft melodious voice, thy air, thy shape,

Were of a goddess—not a mortal maid…”

Both poets understand that Petrarch’s beloved is depicted as inherently more than she is. She is a goddess or an angel, not a human woman. More than this though, both poems only mention her physical beauty. Neither rendition makes any reference to her personality — further implying that this version of the woman is not real or true.

But it is in Sonnet XV, a translation of Petrarch’s Sonnet 279, that Smith’s criticism becomes most pronounced. Within these poems, the speakers are so consumed by their remembering of Laura, now deceased, that she appears before them as an hallucination. She arrives to deliver a speech to the poets, the original from Petrarch’s Sonnet is sweet:

“‘Ah, why are you so aged before your time?’

she asks with pity, ‘why does a sad stream

always flow from your grieving eyes?

Don’t weep for me, my days, in dying,

became eternal ones, and when the light

within seemed to darken, my eyes opened.'”

This version of the beloved shows concern and sweetness towards the poet. She wants to reassure him that she is happy in her afterlife. This idea aligns with his earlier images of her. Her physical beauty, so laboriously described in previous poems, seems inherently linked to being good-natured in Petrarch’s poems. Smith’s version of this speech, however, reads dramatically different:

“To say—‘Unhappy Petrarch! dry your tears:

Ah! why, sad lover! thus before your time,

In grief and sadness should your life decay,

And like a blighted flower, your manly prime

In vain and hopeless sorrow fade away?'”

Unlike the kind-natured Laura of Petrarch’s own imagining, the imagined Laura of Smith’s poem is cruel and emasculating. She accuses him of wasting his “manly prime” by continuously mourning for something that was not his. Smith’s other poems often gender the natural world as a ‘she,’ thus this emasculation is furthered by likening him to a crushed flower.

This poem cements the idea that Smith disagrees with Petrarch for idealising the untrue memory of a woman. This cruel response demonstrates that Laura is not the ‘angel’ that her physical appearance makes her seem. This challenges the traditional Sonnet’s tendency to value the objectified woman, as it shows that women are more than just their appearance. This dissonance between her appearance and her behaviour presents a multifaceted woman — something traditional Sonnets omit.

By taking the position of Petrarch as Smith has, the poet is placing herself as equal to him. For the contemporary reader, this might seem insignificant. However, in an eighteenth century man’s domain this idea would have been transgressive. Smith’s ‘From Petrarch’ poems depict women as capable of independent thought; they are more than just how they are imagined by men.

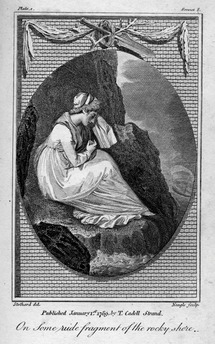

The Sea as Man

Not only do Smith’s poems empower women, they also address her subservient position in society as a woman. This is often done through the imagery of the sea. In several of Smith’s Sonnets, the sea can be interpreted as a symbol for men. The way in which the speaker interacts with the sea suggests that she is victimised by it. These poems express a distinct hopelessness; they can be interpreted as desperate pleas for social change. Sonnet XII and Sonnet XLIV both express this desire.

Sonnet XLIV

This poem, though it is positioned later in the anthology, sets up the idea of the sea as man. In this poem, subtitled ‘Written in the Church Yard at Middleton in Sussex,’ the poet discusses the connection between the moon and the sea. The poem opens, “Press’d by the Moon, mute arbitress of tides.” Already, Smith’s discontentment is expressed within this simple line. The moon is gendered as a woman through the use of the word “arbitress.” Moreover, this woman is “mute” and incapable of being heard.

Despite the moon being necessary for the sea to move as it does, it is the sea that has the visible power. It is responsible for driving “the huge billows from their heaving bed,” not the moon. This can be linked to the idea of childbirth, especially in the eighteenth century, as women like Smith were necessary for procreation, yet still held no power. That was granted entirely to their male counterparts. This idea of powerlessness is completed with the poem’s final two lines:

“While I am doom’d—by life’s long storm opprest,

To gaze with envy on their gloomy rest.”

Smith and the moon are both ‘oppressed.’ Just as the moon is forced into silence by the sea, Smith insinuates that women are forced into silence by men. Moreover, she is envious of their position of power, hence her interjection into the male domain of writing. While this poem can be, and indeed has been, interpreted in different ways, Smith’s life experiences make this a viable interpretation. The poet’s willingness to transgress social boundaries suggests that Sonnet XLIV is another way for her to express her desire for societal change.

Sonnet XII

In this poem, subtitled ‘Written on the sea shore,’ the poet depicts herself caught in a dangerous storm near the sea. To begin with, the poet is observing the scene whilst sitting on a rock fragment; the storm “suits the mournful temper” of her soul. However, as per the Sonnet structure, the focus of the poem changes part way through, and suddenly she is positioned amongst the action:

“Already shipwreck’d by the storms of Fate,

Like the poor mariner, me thinks, I stand,

Cast on a rock; who sees the distant land

From whence no succour comes–or comes too late.

Faint and more faint are heard his feeble cries,

‘Till in the rising tide the exhausted sufferer dies.”

Continuing the idea of the sea as a symbol for men, Smith is depicted as wholly powerless. Against this force, she is unable to fend for herself. This parallels Smith’s relationship with the men in her life. After being forced into marriage with her husband, his so-called ‘true personality’ increasingly became apparent. He became more violent and disloyal as their marriage continued. 13 Like the mariner that she embodies in this poem, trapped in a dangerous situation, Smith was also without “succour.” The power of the sea symbolises the power that Smith identifies in men.

Smith’s proposed solution to the mariner’s problem, and by default her problem, is death. Thus, she presents death as the only viable escape from her oppressed situation. By expressing this desperation, she can be seen to plead for social change. She is almost begging for improvement to her situation; she wants to give women more power.

A Poet Worth Remembering

Despite her influence on the literary tradition, the work of Charlotte Turner Smith now falls somewhere between disappearance and immortalisation. During the nineteenth century, her writing was almost forgotten altogether. It was not until the 1980s, when literary critics took a renewed interest in the poet, that her legacy was increasingly acknowledged once more. If for no other reason, Smith should be remembered for her creation of beautiful and thoughtful poetry. Loaded with vivid imagery and thought-provoking symbolism, Smith’s Elegiac Sonnets hold their own when pitted against any other eighteenth century poet.

Dismissing her as just a popular poet is too hasty, though, when one considers the significance of this anthology. With this collection of poems, Smith was able to break free of two separate forms of confinement, the first being a literal prison. The second, arguably more significant, form was a societal confinement. Smith’s refusal to uphold the patriarchal norms which oppressed her set an empowering precedent.

More than this, though, she was a trailblazer of the Romantic movement; she was writing in an identifiably Romantic style before most others. As a woman, she set the scene for her male poet peers. This point alone suggests that Smith is an artist deserving of more recognition than she currently receives.

According to Smith herself, this collection was almost never published. She explains her friends’ interference with her Sonnets in the anthology’s preface:

“Some of my friends, with partial indiscretion, have multiplied the copies they procured of several of these attempts, till they found their way into the prints of the day in a mutilated state; which concurring with other circumstances, determined me to put them into their present form.”

If it were not for those allegedly peer-pressuring friends, these Sonnets might never have seen the light of day. If such a claim is true, literary history owes much to these meddling people. Charlotte Turner Smith’s Elegiac Sonnets is a collection that deserves to be preserved, studied, and admired. The poet spent her life empowering women with a Sonnet.

Works Cited

- Dolan, E 2003, ‘British Romantic Melancholia: Charlotte Smith’s Elegiac Sonnets, medical discourse and the problem of sensibility’, Journal of European Studies, vol. 33, no. 3-4, pp. 237-253. ↩

- Tayebi, K 2004, ‘Charlotte Smith and the quest for the romantic prophetic voice’, Women’s Writing, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 421-438. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Roberts, B 2017, ‘”Breaking the Silent Sabbath of the Grave”: Charlotte Smith’s Sonnet XLIV and Her Place in Literary History’, European Romantic Review, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 549-570. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Hunt, B 2004, ‘Wordsworth and Charlotte Smith: 1970’, Wordsworth Circle, vol. 35, no. 2. ↩

- Tayebi, ‘Charlotte Smith and the quest for the romantic prophetic voice’. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Rambler 2015, Charlotte Turner Smith: The Grandmother of Ecofeminism, Literary Ramblings, blog post, 30 May, https://www.literaryramblings.com/charlotte-turner-smith-the-grandmother-of-ecofeminism/. ↩

- Dong, I, Gillespie, C and Wamae, H 2018, Charlotte Turner Smith’s “On the Departure of the Nightingale”, British Literature, blog post, 18 March, https://surveyofbritishliterature.wordpress.com/2018/03/18/charlotte-turner-smiths-on-the-departure-of-the-nightingale/. ↩

- Myers, M 2014, ‘Unsexing Petrarch: Charlotte Smith’s lessons in the Sonnet as a social medium’, Studies in Romanticism, vol. 53, no. 2. ↩

- Dong, Gillespie and Wamae, ‘Charlotte Turner Smith’s “On the Departure of the Nightingale”’. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Very good article. I am not quite sure why she has been so neglected as these poems are interesting and original examples of the sonnet form.

Thank you! I’m not sure why she has been so forgotten, either. She was clearly a woman of immense talent.

The Emigrants is worth reading for its historical significance, but I found it a bit too long.

If that’s the one about the French Revolution, then yea, I hear ya.

In my continuing pursuit of the works of women writers who were influential during their lifetimes but have been forgotten by a patriarchal system that has favored men, I finally land on Charlotte Smith. Great coverage of her.

It is truly a shame that she has been so forgotten, because her writing is really wonderful.

Her books are fairly long and exhausting. I don’t recommend it to anyone who isn’t into English Literature at an academic standpoint.

Agreed. I don’t love the writing style. Still, worth a read for what it adds to historical knowledge of the literature at the time.

She gave a fascinating insight into women’s lives and concerns at the end of the eighteenth century.

Indeed, she did!

Glad to see this article up! Thank you for introducing me to such an important and influential writer.

Thank you for your ever helpful suggestions! If you are interested in poetry at all, I recommend giving her collection a read. I am not a big fan of poetry normally, but there is something about her writing that I was instantly drawn to.

I can be a little choosy when it comes to poetry as well. Just out of curiosity, was there a particular poem that drew you in initially and made you want to write about her?

Sonnet XII, ‘Written on the sea shore’ is my favourite and got me really interested in her poems. Sonnet I is another wonderful poem. Both are beautifully written and vivid, but, in my experience, not so complex that the reader is left confused. I also like how pessimistic and dark her writing often is (a breath of fresh air after reading some of the entirely too-rosy nature poetry of her time).

I just checked them both out in their entirety. You’re right! They’re beautifully melancholic, accessible in their simplicity, and visceral in nature. Yeah, I think it’s refreshing when poetry doesn’t shy away from feelings of pessimism and darkness. I think they both capture the often lonely nature of being an “artist” (especially when “the Muses” have neglected to pay a visit recently – or if they visit far too often, to the detriment of family and friends). She captures this Catch-22 situation perfectly. I’ll definitely check out some more of her work! Thank you for the recommendations.

Lovely, thorough work. Thank you again for bringing attention to a little-known poet, and a female writing in a patriarchal world, at that (more patriarchal than the one we have, that is).

Thank you for your kind words and your suggestions when editing! It was through looking for a physical copy of her poetry collection, and struggling to find one, that I realised how little-known she was. I knew I wanted to write about her and hopefully introduce her (and the contributions she has made to literature) to some new readers.

I’m honestly not the biggest fan of poetry at all, but Smith was required reading for one of my uni courses. All I can say really is that I was slightly indifferent throughout it (perhaps due to a general avoidance of poetry on my behalf). I didn’t love it to the point of gushing over it, but I have read much worse poems.

I was (and still am) the same. I struggle reading poetry because I find that I often just don’t ‘get’ it. I don’t often seek out poetry on my own. But I found Smith to be different, she’s articulate and makes her point crystal clear.

In the last few months I read some of the writer’s novels and what impressed me is her very poetic writing. So this article landing on my lap today couldn’t have been any better.

I have only read The Old Manor House. Smith’s political and social criticism shone through the text: in her descriptions of war, of legal malpractice, of human selfishness and insensitivity.

I had to read this book for a class at university, but let me tell you, it was WILD.

Just from your description of the book alone, I’m adding it to my list of books I wish to read! I think if her books are anything like her poems, I’ll enjoy them a lot.

I read “Emmeline” not long ago. It was fun to read about a woman that every man seemed to fall in love with, not because she was beautiful but because she had perfect manners.

Worth a read, but Smith moved on to better things.

I love gothic feminist writers. Charlotte Smith embodies the GOthic novel. Weaving tales of intrigue and sorrow.

I have recently discovered her in a poetry class I’m taking at York University and I admire her work greatly. You have helped me to understand her work.

I wish you luck in your poetry studies, and I’m pleased my analysis could be of assistance!

Fascinating poems and analysis – thank you. One of the reasons I find C18th women’s writing so interesting is precisely because it so often has to do this dance (where the female author both hides behind & simultaneously exposes ‘femininity’).

I agree completely! Some believe that Smith lied when saying ‘my friends published this’ in order to justify her transition into the public sphere. It was potentially a way of maintaining the idea of her ‘femininity’ and place in the private sphere, whilst simultaneously being in the allegedly ‘masculine’ sphere.

Charlotte Smith, still much underrated but so very good!

“Ah! thus man spoils Heaven’s glorious works with blood!”

My favorite quote of hers.

I recommend her to anyone who is a Austen/Brontes/Radcliffe/Thomas Hardy fan.

She is a hidden treasure.

Her “good” characters are either ridiculous or highly problematic, but her “bad” characters are exceptionally well-drawn.

Aren’t all “good” characters either ridiculous or highly problematic?

Smith’s sonnets are surprisingly accessible and vary in subject matter from nature to human emotions.

It’s kind of interesting to think about how people once considered poetry a male domain, considering nowadays poetry seems to be thought of as feminine, and the majority of people who write poetry, especially “elegant” poetry, are women. Most of the men who write poetry in modern times seem to be musicians.

I agree completely. Writing this, I realised that I have always subconsciously associated poetry with women. It was a little jarring, then, to read that this particular woman was so out of place amongst the poets of her time.

From a time where poetry was something simpler.

Beautiful examples of how sonnets can be used outside of love poetry.

Charlotte wrote some of the most complex stories of the 1790s.

I love Smith’s sonnets.

“Beachy Head” is a powerful piece of writing that should be part of the Romantic cannon.

Very interesting commentary – great help with my studies.

Charlotte… Brilliant moment of critique, satire and awareness of how fucked over women are in that particular society. But it doesn’t fall completely to self pity.

Love the social critique in her writing.

I agree! Some say that when you read and interpret literature, you do so with a certain ‘lens’. This is pretty much what you personally like to look for in the text. I usually have something of a feminist lens when reading, so I am drawn to writers like Smith who directly address the position of women.

That being said, I believe she does this social critique wonderfully.

Beautiful poetry but a sad life story. I look forward to reading her novels.

I look forward to reading them, too!

Smith is stronger with form than with language.

The poem I like the most is ‘Two Part Prelude’.

Wow! I remember in my English undergrad I wrote about Smith for British lit. It was amazing learning and reading about a female poet in a genre (Romantic poetry) where mostly men receive recognition.

I enjoyed your analysis of her poems, especially the sea metaphor. It was very insightful.

I’m glad you enjoyed my analysis of her poetry, thank you for the kind feedback!

But I agree, I took a class on Romanticism earlier this year and I believe she was the only female poet we covered. Aside from the fact that I liked her because she was doing some cool stuff in a male-dominated field, I genuinely enjoyed her poetry more than I enjoyed the work of her male peers. A truly great writer!

There is an interesting contrast with the other, more famous female literary figure Jane Austin. Both accommodated their audiences with the literary trends of their era. However, this is the only major point of similarity that I can identify.

Smith very much fits the proto-Romantic mold (because she still is writing in the Enlightenment Era) with some emotive content and nature themes. This is fairly standard for writing from this time and sub-genre.

Austin, by contrast, accommodated a number of novel literary trends brought in my the Era of Romanticism, but ultimately was literarily more conservative and Enlightenment-weighted.

Just some food for thought.

A very thorough, thoughtful article. Older poems are so often disregarded today but they hold so much depth, even a radical sort of depth, that is relevant to this day. Before this article I had not heard of Charlotte Turner Smith, but I had heard of all the male poets she had later influenced, which ultimately, I think, proves the point of your article. I appreciated the muse by muse process you employed for breaking down Smith’s poems and revealing her inner consciousness. Incredible work!

Thank you so much for your kind words! This is exactly why I wanted to write about her. She had such an influence on many big poets, yet her name has been almost forgotten along the way. I am so glad you enjoyed my article!

Great article! I found it extremely interesting. I have never heard of her before, and I am well versed in poetry, so I am also unsure why she has been neglected. Her writing is immaculate, such a pure form of the sonnet style. Thank you! I will be sure to look at more of her writings.

Lovely article! Thank you for introducing me to such an important and immaculate writer.

Really nice article,thank you to author of the article.

Thank you for a very well-written article!