Comic Books, Adults, and a History of Stigmatization

Comic books, perhaps best known as the staple for superhero fans, have indisputably become a major part of popular culture. However, most readers of comics will likely encounter someone who assumes that comics only possess simplistic and childish stories—and that they are simply not worth one’s time. This stigma seems to assume there is an age at which one “grows out” of reading comics, even though they simply tell a story through images like movies. No one would dare suggest movies or even books as a whole medium are only appropriate for a certain audience, so where did this stigma come from and why do comic books—and their older readers in particular—face this judgement? More importantly, have the efforts within the recent decades to diversify the content of comic books and shift the favoured audience contributed to a changing idea of comic books?

Comics for Kids

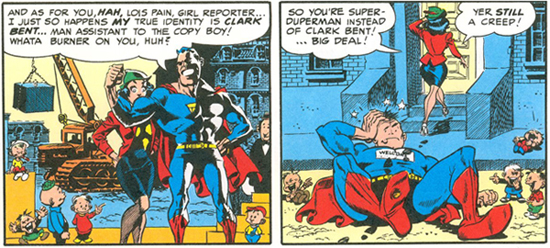

Comics, in the form of sequential and juxtaposed images, have existed for centuries and were even used in satirical cartoons and “funnies” strips in the 1800s. Modern comics as we recognize them now were only introduced and popularized in American society in the 1930s, during the Great Depression. It almost comes as no shock that comic books—with their bright colours, and heroes with strong moral compasses and the abilities to do fantastical things—became extremely popular. Children, specifically young boys, were the target audience and the birth of the superhero comic in this time gave us some of the most familiar and popular characters in the form of Superman and Batman. Who wouldn’t want to be like Superman or Captain America, battling evil and saving the world, especially during the Depression and World War Two?

The contents of comics eventually came under fire and the most recognized opponent was Fredric Wertham, a psychiatrist who crusaded against violent images in mass media. In Seduction of the Innocent (1954), he argued the depictions of violence, drug use, and sex had a detrimental effect on the development of children (Coville; “Seduction of the Innocent”). He specifically linked children who were exposed to violent images to juvenile delinquency, showing the dangers of children imitating what they read or watched. Even the beloved superheroes were criticized: he described Superman as a fascist and suggested the Batman stories had a homosexual overtone (Coville; “Seduction of the Innocent”). Some of Wertham’s research has been disputed and proven as falsified, but he fuelled the idea that comics were not suitable for children.

At the same time Wertham conducted and published his research, the Comics Code Authority (1954) was created as a way of regulating the material of comic publishers. Its code—the “Comic Book Code”—lasted until the early twenty-first century and a small stamp appeared at the top corner of the covers of whichever comic books obeyed it.

The code’s original regulations included portraying crime only as an immoral activity and having the criminal punished by the triumphant good figure to deter children from crime, banning excessive violence and depictions of horror, prohibiting all representations of creatures like vampires and werewolves, and eliminating anything sexual (“Good Shall Triumph over Evil”). The code was occasionally updated but until publishers stopped conforming to it or developed their own rating system, it determined what was acceptable for its child-focused audience.

Criticisms and Codes: The Result

In many ways, the backlash and the comic code helped reinforce the notion that comics should be exclusively for children. Comics originally appealed to a younger audience with its heroes and awesome adventures, but the more mature activities and images could at least appeal to an older audience. The outcry against comics and the attempts to make the content as harmless as possible to children likely narrowed down the audience to almost exclusively young readers.

Comics were also considered “low culture” and part of the degrading mass culture since they were cheap and easily distributable. This relegated them to the lowest position on the supposed hierarchy of literature. Just like how we give children picture books with little words and then shift to stories with less pictures once they learn to read and then to novels without any pictures, there seemed to be a belief that reading comics was a passing phase. Once children grew up, they were meant to abandon comics and move onto better literature.

You could easily start tracing the stigma of adults reading comics from here because comics were culturally and ideologically reinforced as children’s things, surviving almost solely because of their popularity than their worth.

Comics for Adults

Since comics were ruled by the Comic Book Code, the question becomes how or why adults would even wish to read comics. Comic books, by definition and by regulation, should have been child-friendly, inoffensive, and too simplistic for most adults to even spare a glance. And of course, the notion of comics as childish likely warded off older readers who might have enjoyed them.

From these strict regulations and lack of freedom for some artists, underground comix emerged. And from here, the stigma of adults reading comic books becomes slightly more complicated.

While the Comic Book Code carefully monitored the content of all the mainstream publications, an underground comic counterculture became popular in the late 1960s. This created comix, which used the same form as regular comics, but they were not mass-produced or readily available to the public. Mad Magazine (1952-present), which satirized everything from pop culture to politics, had a great influence on underground comix. The comix themselves followed this satirical tone, poking fun at societal norms like the nuclear family, and explicitly exploring subjects that were outlawed in mainstream comics such as sex and drug use (“Underground Comix”).

The counterculture movement, spanning the comix and even adult cartoons like Fritz the Cat (1972), brought media that typically targeted children to adults. Even The Simpsons (1989-present) has its roots in the counterculture movement. Its creator, Matt Groening, was approached to create the show because of his underground Life in Hell (1977-2012) comic strips—and no one can deny The Simpsons’ role as a hugely successful satirical cartoon appealing to children and adults alike (Murray). Another obvious legacy of the underground comix are the alternative or independent comics, like Dark Horse Comics, which still offer different stories and styles that contrast the mainstream superhero comics.

What the underground comix illustrated was that comics were not only for children. They showed the possibility of making comics that could be adult in tone and content, making jokes that a younger audience wouldn’t understand. The successes of the underground movement and the persistence of certain aspects in modern culture have definitely helped challenge the stigma of comics as childish or unsuitable for adults.

The Rise of Graphic Novels

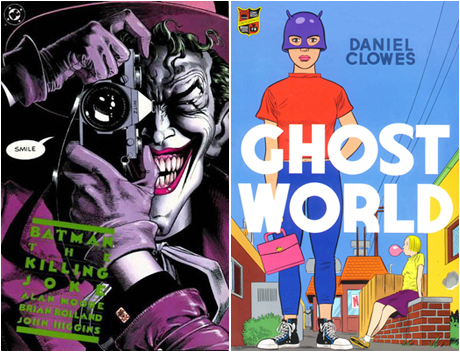

The last piece in the stigma of adult comic book reading is the creation of the ever-popular “graphic novel.” This was a term popularized in the 1970s to distinguish the works dealing with more complicated narratives from the stereotypical images of simple and colourful superheroes commonly associated with comics. In a way, it helped artists who might have been otherwise ridiculed for pursuing a career in comics.

In publishing terms, “comic books” now describe the serialized issues bound like magazines, while “graphic novels” often have the glossy cover and bindings of a regular book. Both use the same form of juxtaposed and sequential images, even if the use of colours or the content of the stories may vary. Graphic novels might arguably have more freedom in their content, ranging from the contemporary superhero narrative found in Watchmen (1987) to the iconic story of the Holocaust in Maus (1991). While they tend to deal with mature themes, they don’t target an exclusive age group so its audience can range from young preteens to adults—but when it comes down to it, graphic novels share many key similarities with comic books and are still technically comics.

The stigma surrounding adults reading comics is perhaps most clear when discussing comic books versus graphic novels because we have these two terms. It’s important to first note that neither “comic books” nor “graphic novels” describe the content of the works because neither are limited to specific genres or art styles (especially since the comic book code became void). Saying you are reading a “comic” will not give anyone an accurate indication of what is inside the comic.

These terms become harmful when people use “graphic novel” to distinguish their preference of reading material from “comic books”—as if the former is superior to the latter. This is definitely a flawed idea and becomes very blurred when some graphic novels, like the highly acclaimed Maus, are simply a collection of previously serialized comics. “Comic books” are still largely associated in popular culture as cheap paperbacks with colourful stories reminiscent of the early comic code era, while “graphic novels” have been popularized as more mature and complex. This makes some comic book readers quick to correct anyone who calls their reading material “comics,” as though reading comics is embarrassing but graphic novels are worthy of their time—which unfortunately only fuels the stigma that comics are only suited for children.

A Changing Opinion

There have been many historical and even cultural ups and downs in how comic books have been received by readers and critics, but the response to them has been steadily improving.

For example, one major benefit to the emergence of graphic novels has been the fact that there is now a wider availability of reading material for people regardless of their age. Graphic novels have given teenagers and adults a way of enjoying the content of comics—regardless if it’s a crime, superhero, or even contemporary story—without being ridiculed for it. Even if graphic novels continue to be more culturally respectable than comic books, they have at least helped reduce the stigma that adults shouldn’t read comics.

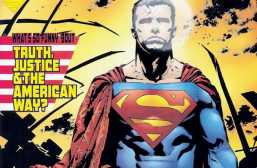

Additionally, even if you only look at superhero comics, we have been given many characters that perhaps become more admirable as you get older. Many have become more human and relatable with backstories and weaknesses, so they’re not just invincible or flawless beings. Some characters have visible or invisible disabilities, ranging from blindness to depression, and can still kick ass. There is a diversity in comics that is only possible with the multiple iterations of certain characters, the endless possibilities of parallel or alternate universes, and the new writers and artists who often adjust things to contemporary times. Even though the characters do crazy things we can’t imitate, they can be as inspirational as Hermione Granger or Sherlock Holmes.

And of course, in the last fifteen or so years, there has been a visible change to how comic books are approached and publicly received due to the explosion of successful comic book-to-film adaptations. The comic book-to-movie possibilities are currently dominated by superheroes in the expanding Marvel Cinematic Universe, the long-standing X-Men franchise, and the recent DC Extended Universe—but there have been successful non-superhero adaptations like Sin City (2005) and V For Vendetta (2005). Although adapting a comic book can be risky when aspects of a beloved character or story are changed and this can translate into a box office failure, the successes largely outweigh the failures. Not to mention, these movies have helped expand the appeal of comics to people who hadn’t even picked up a comic before or might have thought it wasn’t for them. Even if they are just casual fans of the movies, this definitely helps the popular image of comics.

What Now?

So does a stigma persist around adults reading comics? Unfortunately, yes.

But as Scott McCloud points out in Understanding Comics, “[i]f people failed to understand comics, it was because they defined what comics could be too narrowly” (3). This is one of the best ways to sum up the stigmatization of comics and their older readers throughout the years. Comics have been re-defined several times since their popularization and have felt the pressure of social or cultural beliefs that have limited their content and audience. But they have also since expanded even if some people outside the comic community still can’t fathom why comics are useful or popular. McCloud sees the many possibilities that exist in comic books and his statement reveals that perhaps there is hope for people’s definition of the medium to expand and resemble the reality of comics today.

Comics—and their reception—have come a long way in the past eighty or so years. And no, it’s not perfect but it’s difficult to erase decades of a certain popularized image of comic books, even with graphic novels and comic book films. But at least comic readers and even casual fans have a community in which they can enjoy an endless supply of amazing characters, art, and stories.

The bottom line is that there is nothing shameful about reading a comic book—even if no one understands it because it’s really their loss if they think anything less of you or what you’re reading. So if anyone asks, Yes. It is a comic book. And it’s fantastic.

Works Cited

Coville, Jamie. “Seduction of the Innocents and the Attack on Comic Books.” Integrative Arts 10. Gregory J. Golda at Penn State University, n.d., http://www.psu.edu/dept/inart10_110/inart10/cmbk4cca.html. Accessed 14 Jan 2017.

“‘Good Shall Triumph over Evil’: The Comic Book Code of 1954.” World History, n.d., http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6543/. Accessed 21 Jan 2017.

Maslon, Laurence, Michael Kantor. Superheroes! Capes, Cowls, and the Creation of Comic Book Culture. Crown Archetype, 2013.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. HarperCollins, 1993.

Murray, Noel. “Between Zap and The Simpsons: Matt Groening’s Life In Hell: How Groening brought the underground to the mainstream.” A.V. Club. Onion Inc., 17 Jan 2015. http://www.avclub.com/article/between-zap-and-simpsons-matt-groenings-life-hell-213583. Accessed 16 Feb 2017.

“Seduction of the Innocent.” World Public Library. World Heritage Encyclopedia, n.d., http://www.worldlibrary.org/articles/seduction_of_the_innocent. Accessed 9 Jan 2017.

“Underground Comix and the Underground Press.” Lambiek Comiclopedia, n.d., https://www.lambiek.net/comics/underground.htm. Accessed 16 Feb 2017.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I had someone ask me recently “Why do you read comics?” It took me a minute, but I eventually answered that it was the same reason I watch movies, read books, listen to music, play video games, follow sport and go to the theatre, it’s all just a form of entertainment and if anyone has a problem with that then it’s theirs, not mine.

I used to have a real problem with reading my comics.

I’d get super embarrassed because I guess I had this idea that everyone thought no matter what the subject matter was ‘COMICS ARE FOR KIDS!’, not how I thought at all but still the idea that I would be judged for some reason frightened me.

I was not a shy person at all and had lots of friends who I hid from all of them my love for comics. Anyway the closest book shops and comic book store are about a half hour bus journey from where I lived with my parents, (this was before I was old enough to drive). If I wanted to look around other shops I’d purposely look around them first because I knew that if I bought a comic book it would be torture for me to have to wait to read it. So I’d go pick up my pull or some random TPB from the book shop last and have to wait that long half hour journey before retreating into my room and closing the door to the rest of the world.

However I could never wait, so when I get on the bus I’d run up the stairs and sit right at the back of the top deck so no one would see me reading. This became annoying though because every time the bus stopped I instantly hide the comics in case anyone came and sat next to me.

Eventually I realized that people are to wrapped up in their own shit to care what the hell I’m doing so now I read in public whenever I feel like it. I do notice people looking sometimes but then I realize in most cases that their actually looking at what I’m reading and the art too.

I was sat in my universities library on a study break about a year ago re-reading my copy of Marvel Zombies as like a prelude to Halloween, and kept noticing this guy I was sat across from looking up and then back down to his work. Eventually he looks up and very politely ask what I’m reading and because ‘that is is one intriguing yet fucked up cover’. So I tell him about it and asks if he’d like to have a look.

This brings such a smile to his face and he says ‘okay, thanks’. So I pass my book to him and start doing some work, every now and then looking up to see that his eyes have widened more and more. About an hour passes and puts the book down having finished and says ‘That was Fucking Awesome!’ we got talking and have been good friends since he’s about as if not more into comics than me now too so there’s that.

I guess to sum up my story I now have no problem with reading my comics and really enjoy it, especially during the holidays when I travel a long time via train, and the occasional glances from other people just don’t bother me anymore.

Thank you for sharing! I totally understand this feeling of embarrassment, reading comics in public. Like you, it definitely took me a while to get over it. I’ve had this same experience reading manga too – I took a volume of Fullmetal Alchemist once to university to read before class and was so concerned that people were just looking at its front cover and wondering, ‘What the hell is this girl reading?’

But just as you say, it’s usually an overblown concern – people are usually too caught up in their own world and worries to really care about what *you* specifically are doing. I’m glad you’ve found a way to now enjoy comics as they deserve to be enjoyed 🙂

I guess it’s human nature to want to belong to a group.

Great piece. I just started reading/collecting Graphic novels/comics earlier this year.

With the Walking dead, and the marvel movies Comics are becoming more popular.

There is still a social stigma attached to cartoons, comics and manga that disregards them as being only suitable for children.

Long live les comics ( I think there are far more comics for adults nowadays then there are for chislers. Kids don’t seem to read them at all any more – or is that just me?)

There are way too many comics that are marked as adult/mature and for people from 18 and above. Exceed the output for children. It is my humble opinion.

“Nerd” culture and pop culture have seemed to meld but only to a point. Its ok to like Iron Man because of the movies, its not OK to ready the comic books or know the back story or anything that is different than the movie. I have several friends like this . “Oh im such a nerd, look at me I have a captain america poster on my wall”. Only knows about the movie and nothing else, etc. So while the characters are ok to know if they are in pop culture, its not OK to know the comic books. And if you collect them then you are even a bigger nerd.

Its really sad that this is the way it goes now a days but it is.

Admittedly, I haven’t encountered this problem myself, though I do understand where you’re coming from. When I offer non-movie background on characters to my friends who only know the movie-versions of the characters, they’re generally surprised and interested by the random fact – so that might just be a testament to the kinds of people I have surrounded myself with, and their reception to “nerd culture”.

As I mentioned in my article, comic book characters often have so many iterations that a single movie (or even cinematic universe) cannot even begin scratching the surface – so it’s a shame if people only look at the movie version as the “ideal” or only valid interpretation of the character.

It sounds like you just have shitty friends, if they’re actually giving you a hard time about reading comics while they like comic book characters.

It’s been years since I’ve met someone that had a negative reaction to the idea of a person reading comic books.

Its not mainly friends, but people in general. Look at the majority of comic con attendees, they are not there for comics, they are there for most everything else. I would wager that more than 70% of The Walking Dead fans have no idea that there are even comics and if they do find out about them they think they are based off of the show.

The ideas are popular, the actual knowledge about them is not.

Personally, I think comics are just not as good as other literature, generally speaking. Some graphic novels are obviously better than plenty of books, but they don’t hit the same highs — and there are enough great novels to keep you busy for a lifetime. I know some people may disagree, but when I see something like Watchmen listed as a great book comparable to something like Les Mis or War and Peace, I just can’t agree. Good graphic novels tend to turn on one interesting idea or a couple big emotions while great novels are much more complex (and generally truer to life) and nonfiction books are obviously different from both. Even the “great” graphic novels seem more YA in nuance and depth even if they contain “adult” material.

That said, a lot of the books people read are junk. Why do they read that junk instead of graphic novels or comics? Appearances seems to be a big part of it — and not just worries about what others will think, but people may actually themselves fall for the appearances and the perceived greater worth of books.

Comics/graphic novels are a form. And there is a tremendous diversity of content. There is a lot of “adult content”, yes, and an increasing respect for its possibilities (see: Moore, Chast, Brubaker, Ware, Bechdel, Spiegelman), but the bulk of it is still geared towards younger audiences, and that is still the primary historical association.

I think we need to stop treating it like a genre, and look at it as a specific approach to story-telling, one that can be poignant and mature as easily as action-packed or funny.

I would disagree that comics are not just as good as other literature, although there are some comics of poorer quality than what one expects of literature. The American comics industry and style of ongoing series with a push to produce something every month and get it out there, with possible changes of artists and writers aren’t really conducive to the best work. Also, when the audience is supposed to be children and not adults, those themes are not going to be as involved or well-explored.

However, looking at fiction graphic novels like Watchmen, or something like Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series (or non-fiction ones like Maus or Persepolis), I would argue that those have value as literature–just in a way that most people aren’t used to looking for it. In a comic that is done well, the art is going to have just as much (or more) relevance and importance to the themes and ideas being discussed as the written text. Even the color and lettering choices matter.

Perhaps the numeric majority of what is available is of poor quality, but I don’t think that has anything to do with the capabilities of the medium itself.

Comics are just a different format for communicating ideas. Like all media, it either educates or entertains (or both). If it does neither, it’s probably pretty awful. What I like about the format, is the creativity it allows for the artist and author, and the way that reader interaction is so important. Books tell you what happened, and movies show you what happened. Comics do both, but you get to fill in the blanks between the panels. Even the perception of time is done in the reader’s mind, dictated by the letters and lines on the page. Depending on the artist’s choices, there may be more or less that is left up to the reader’s mind to fill in.

I don’t know if I’m just a particularly unobservant reader or how other people perceived this, but while reading Watchmen for the first time, I had no idea who the person at the newsstand with the “The end is nigh” sign, or even that he was important or relevant as more than a character in a background plot, like most of the characters at the newsstand; I hardly noticed him. In the movie, it was instantly apparent that he was an important character and not part of the background because the camera focused on him and the rest of the newsstand scenes were gone, so those scenes with him in it didn’t blend into the remainder of the background newsstand setting. Similarly, the “Tales of the Black Freighter” portions from the comic cannot be integrated well into a film, but the way they are incorporated into the comic is really cool–these are elements of the comic as a medium that I feel could not be done well in any other medium.

Well put!

As an English major myself, I can understand why classic literature is so highly regarded – though even I sometimes question the process of canonization that elevates certain works and disregards others deserving of more exposure. However, disregarding comics as a whole merely because they seem to be less nuanced than certain literature/books is a damaging approach to comics that I entirely disagree with.

I actually took a “Comics and Cartoons” course last summer as a part of my English degree. I took it mostly because I was a casual manga and comics reader, loved superhero movies, and wanted a greater exposure to comics as a medium. I ended up becoming exposed to a lot of the great titles I’ve mentioned in my article, and the course as a whole shaped how I now view comics.

I also realized how much you can discuss about comics in terms of colour, composition, use of frames, style of art. As an English major, I am used to discussing themes, characters, and how sentences are structured, or analyzing stories through specific literary lenses. But comics have an entirely visual element to them that brings so much more analysis and it was a genuine pleasure writing essays on how these elements enhanced the comics’ stories and how you could read them.

I want to get into them, I just don’t know what to get into.

Try going to a ComiCon in your city. You can look up the next date. I am a mom who really wanted my younger son to read more and we went to a ComiCon and got 5 comics for a dollar. Next thing you know, he is really into graphic novels. I even bought a few graphic novels and Star Trek books.

ComiCon is a great way to check out so many comic books to your hearts content and talk to the vendors. They are usually very passionate about their field.

Good luck!

Saga (image comics) Death Vigil (image comics) Hellboy (Dark Horse) Chew (image comics) The Dark Knight Returns (DC comics) Sheltered (image comics)

Few suggestions.

I’d certainly rather read the grown-up stuff.

I’m wondering if we’re losing an entire generation… I suspect most of us graduated from serialised fiction to the more advanced graphic novels as we got older ( certainly I began as a regular subscriber to 200AD, Battle and Misty), if there’s nothing for kids to graduate from I’m wondering if they’ll even be tempted to pick up the more challanging stuff later in life? Maybe I’m wrong ( I confess to being very out of touch I must admit) but it seems to me that the grand old tradition of the multi-story serialised young adult sci-fi/war/fantasy comic has gone out the window?

I think a lot of people assume that comics are for children, even though there are plenty out there that I wouldn’t want my kid looking at yet…

Great article. A better conception of stigma can enhance the analysis of popular culture.

Excellent article. There is such a great and complex history to comic book culture in the U.S. From the comic books ties to anti-fascist resistance to issues of censorship during and after WWII. I like the angle you took here, very interesting.

Thank you! Comic books have a really rich history that reflects many real social and political anxieties – especially post-WW2 and during the Cold War, as you’ve mentioned – and I hoped to uncover some of those complexities and the evolution within my article.

Really great last image! Sums it all up.

Media portrayals of comic book fandom routinely depict the comics community as a masculine space, one in which the female fan is an anomaly.

Yes, but yet women reportedly represent a growing number of comic book purchasers and convention attendees.

Many female comic book fans render themselves invisible in the comics community out of fear of stigmatisation, from both non-comics fans as well as male members of comics fandom.

Well, female fans in the States experience fandom as members of a culture that is coded as masculine.

I feel like there’s still a social stigma with, say, reading a graphic novel at your favorite coffee shop. People who read digitally on tablets probably won’t come across this thought since using a tablet is pretty much socially accepted.

Do you care or not care what people think? Do you just read from home privately?

Nowadays, I read out in public all the time, floppies and trades both. In all honesty, it seems that nobody has ever even taken notice.

Going to a coffee shop to sit down and read with a latte is one of my favorite leisure activities. When I began reading comics, I felt the stigma, too, and for a long time did not read in public. But once I “jumped in” so-to-speak, the anxiety dissipated after the first few forays and now it ain’t no thang.

I read comics on public transit all the time. Ten years ago people often said dumb stuff to me about it, but nowadays with the explosion of superhero movies that almost never happens.

That said, I do try to stick to books that I know won’t have incredibly violent/sexual imagery in them when I know I’m going to be in close proximity to other people just to avoid any awkward comments.

I read on my tablet and bring hardcover and tpb’s to work to read all the time. Everyone knows I read comics at work. No one makes anything out of it or seems to care one way or the other.

In the past few months I started going to one of my favourite coffee shops after picking up my comics on Wednesday and reading what I picked up that day while sitting there for a little while. I don’t really care too much what people will say or think about it anymore, I enjoy sitting there reading them so that’s what matters to me.

I read them on the bus or waiting at the stop. Most of the time, I don’t really care. That’s my one time to read, and I’m sure as hell not going to let fear of judgement prevent me from doing it. Though I’ll admit, when reading certain books (cough Saga cough), I do feel a little weird because I know if I turn the page there could be a spontaneous sex scene, which is a little awkward. I just tilt my book up and sit in the corner so no one can read over my shoulder.

I was reading Saga at work and thought I was in the clear because I was already aware of the robot sex pages…but then he got to The Sextillion and I knew I was better off not chancing it.

I read on my tablet, but I can’t see giving a crap what people think. I’m in my late 30s, with a wife, good job, and a house. I’m going to do what I want, if someone doesn’t approve, they can f-off. I don’t need the validation of strangers.

This is a cool article, and you picked some great sources. I just started reading comics and graphic novels, but have found them enlightening. I’ve been drawn to manga, and Tezuka’s work is pretty awesome.

Really interesting article. You have great comics studies here on The Artifice.

I have to admit I have a disdain for those who look like ‘Comic Book Guy’. I just feel like it hurts the cause.

Why shouldn’t people who look like comic book guy get that same choice?

I’m not saying you need to be athletic, good-looking and clear-skinned. I don’t even meet that definition all the time. I ultimately don’t care who reads comic books and where. The more the merrier! I’m just saying that I don’t particularly like it when the person I see sitting by themselves in the hallways at uni reading Deadpool or Captain America looks like your typical “nerd” that cares next to none about how they present themselves to the world.

I wish I didn’t care but I do. Mostly because I’m too self aware for my own good, I’m slightly vain and I’m a bit of a social climber. It’s probably not that it hurts the “cause” but that I feel that it hurts me.

I mostly buy comic so I have something to read on my breaks at work, usually while sitting out on the patio.

It’s funny. I dunno if it’s because I work in a rich area or what, but adults (quite a few customers and one now ex-co-worker who wouldn’t shut the hell up) actually make fun of the fact I read them in sort of a malicious way.

It DOES make me smile, however, when kids notice I’m reading a superhero book and get super happy. Favorite quote from a little kid in a Spider-Man shirt: “I can still read comics when I’m grown up?!? Mom! Grown ups read comics, too!”

It’s a shame you’ve had these experiences – and that these people have a narrow understanding of the wonderful content of comic books. It’s certainly an example that helps prove my point here.

But that is an incredibly adorable quote and here’s to hoping that kid doesn’t “grow out” of comics just because he’s told to.

My kids are regular customers at my local shop and the owner is always super awesome to them and even talks about the kids comics with them like he does with adults.

My wife grew up reading comics, I did not.

She would get her weekly pocket money and run straight down to the convenience store to get the latest issues of X-Men, Daredevil, and Batman.

I was told that I would poison my brain with imbecilic writing and bad art. When I got a little older and my friends showed me some comics they had, I couldn’t make any sense out of them. I knew Spider-Man, Batman, and Superman, easy. But Wolverine? Green Lantern? These characters were cryptic mysteries to me. Even straightforward characters like Captain America have several layers of context to them, without which the whole notion simply crumbles. Never mind the ensemble comics like X-Men or Justice League. When you open up a comic book in the middle of an arc, if you don’t know the score, it’s like trying to decipher hieroglyphics. Who’s that guy? And he can do what now? And his teammate there is what’s-her-name who seems to hate pants. The bad guy is a what now? And as soon as I have all this figured out, the issue is over and I’m going to have to wait to find out what happens? Eff that, I have a stack of novels that are complete stories and aren’t anywhere near as opaque, thanks very much.

My wife, especially in recent years, has taken my apathy toward comic books as something of an affront. She’s asked time and again why I don’t enjoy what she does, and she has taken to picking out comics for me that she thinks I will like. As I’m older, I have preferences that tend to veer away from the more well-known stuff. I have a taste for mysteries and crime dramas, so I’ve found titles like 100 Bullets, Powers, and Stumptown to be very enjoyable. I like cyberpunk, so I’ve been reading Lazarus, which is not traditional cyberpunk, but still deals with themes of transhumanism and corporate feudalism.

The bulk of what we think of when people say “comics” is the kind of stuff that you see in Marvel movies- bright characters having much larger-than-life adventures, written in a fashion to drag the story out over multiple issues and interspersed with advertisements for junk food, merch, and movies. Titles that break away from that mold do not enjoy nearly the same media presence or, let’s face it, budgets, as the traditional “hero” comics.

Who isn’t a fan of superman!?

Why don’t we all agree that when we see someone reading a comic. (And this is easy for me because I live in NYC and it takes all kinds.) We say to each other, “Hey man, what are you reading?” whatever it is “Cool keep on supporting the industry we love! And if you like this have you read that?”

Here’s to happy comic-book-reading on the train home from work!

Read with pride ladies and gentleman! Read knowing that you are privy to a world of creativity and beauty. A literary and visual medium. The best of all mediums!

This article raises the question of how much inspiration and creative genius was killed by forcing the earlier comic books to be child-friendly. We already know that it had its benefits because it sparked the fire for comics to rebel against these codes. This created an entirely new branch for creative ideas but we are still missing what could have been. In addition, the stigma around comics being for children is definitely something that has affected myself from ever being able to get into comics. It is quite sad to realize that listening to these stereotypes have prevented me from experiencing this type of art.

This article raises the question of how much inspiration and creative genius was killed by forcing the earlier comic books to be child-friendly. How many heroes that we know of today would have been altered if the regulations had never come? It’s clear to see that no matter how long the corruption of innocence was prevented it has finally hit our culture in the media. So was it really necessary to even try in the first place?

Karen offers a tidy treatment of comics stigmas in the US in the late 20th century. The incongruity between major AAA-screen superhero blockbusters and comic book store declines (despite their integration with hipster and “local” rhetorics) is one I often pose to students. Or the overblown hype, especially in education, for the *March* books, which are part of the graphic-novel publishing phenomenon rather than representing anything noteworthy for comics fans and scholars.

One note I’ll add is about the focus of the essay. Scholarship and other discussions of the comics medium and stigma often are contextualized globally. Comic books and graphic novels have long traditions in France and Japan, for instance, and don’t have parallel stigmas that associate the medium with vacuous, juvenile, superhero, or socially- or morally-repugnant stigmas.

I guess I’m an adult. I love Noelle Stevenson. Her graphic novel “Nimona” is amazing. I wish more people would give it a chance.

I adored Nimona! I think it’s very aware of itself as a graphic novel, and a decent starter for anyone wishing to get into the medium.

My work at a comic store led me to meet families looking for role models (see Lumberjanes, Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur), older men looking for fond memories (old Blue Beetle and Swamp Thing), folk looking for alternative mindsets (1970s underground comics and zines), TV/movie/game fans looking for the springs of inspiration for their new favorite obsessions (Injustice, Black Panther), curious professors looking for nonfiction work (March, Fun Home), and excited young people getting into beautiful and unique storylines (Saga, Papergirls) or seeking representation (Totally Awesome Hulk, Ms. Marvel, Batwoman).

Comics are not one genre. Try some webcomics. Try Ody-C, try Wicked + Divine, try Fun Home, try Vision. Try something new. You’ll find something for you.

All great suggestions, and a wonderful way of breaking down just how graphic novels offer an assortment of genres to such a wide variety of people. It’s almost overwhelming to pick *one* graphic novel to start with if you’re new to it, but I definitely agree that there’s something out there for everyone.

I still think comic books are for adults, not for kids, at least to a certain age…

I always psyched myself out of reading comic books in high school. It was never an age thing for me, though.

I psyched myself out for the same reason I stopped playing video games and full-contact sports – they were “boy” things.

I never thought that only boys should read comic books and play video games, but unfortunately, I was stuck amongst people who believed that the only reason I played video games and read comic books was because I wanted all the boys to think I was cool.

There was always that shadow of “you don’t really know anything about comics and video games, you’re just talking about it for attention”.

I’m glad I grew out of that conforming mentality, though. I’m in university now, and whilst some of my friends jokingly calm me a nerd, I’ve yet to meet someone that’s told me I’m too old for comic books.

I’m just lucky, I guess.

I adore comics from my very childhood.

I think that the great thing about comics is how universal it is. I love how a dark drama TV show can originate from the campy Archie comics. It’s great source material that is accessible from many different platforms. Whether it’s for kids or adults, doesn’t really matter because people can get them from anywhere.

I Read through your article and really enjoyed it. I too LOVE comic books however I never really got overly embarrassed reading them in public. The main thing I generally get embarrassed about is going into a comic book shop and walking out with a collectable or Action Figure

This is a great overview of a stigma that I think many are all too familiar with. I can honestly say that this stigma pushed me away from comics for years even though I always had a deep interest in the medium and even attempted to create my own at one point. My time in college slowly introduced me to a community that was willing to view comics as something respectable that could be studied in many of the same ways as traditional literature. Now, I collect comics and graphic novels, but I still feel a touch awkward when reading them in public.

I think one of the biggest benefits in the last few years is the Image company. Many of the titles that they publish like Saga, Southern Bastards, Chew, The Walking Dead, and East of West are extremely intelligent and offer a wealth of literary study while maintaining entertainment value. And to a point made in the article, selling these as single issues that are later collected in volumes bridges that gap between the two formats pretty well.

Unfortunately, there will probably be a permanent stigma in the U.S., but at least titles like Maus, Watchmen, Sandman, and Persepolis are drawing attention from academics and the literary world that elevates the medium closer to the status it deserves.

I’m currently enrolled in a graphic novel course for my PhD and I wholeheartedly agree with your assertions here. Scott McCloud’s books are brilliant and I think they’re helping to break the stigma around adults utilizing graphic novels as a literature genre. Something interesting that we’re working on is bringing graphic novel to the English composition classroom as a multi-modal educational tool– it allows students to engage and both textual and visual rhetoric as well as giving them a platform of expression that they may not have used before!

Thank you for your comment! I loved McCloud’s books – definitely useful for anyone wishing to explore how comics are structured!

The comic book course I took in my own undergrad focused on breaking down the stigma of comic book reading and how you can study them just as you would any other work of literature (which I appreciated, being an English major myself).

I definitely hope graphic novels will be used in English classes and taken as seriously as written novels or poems in the future.

Superman is the archetypal; creature of Jesus.

He’s not.

Nice article!!!

One of the problems (for comics) is that they are often judged in the public mind by their worst, most trivial instances. The stigma associated with them means that many people don’t even look at what’s out there. It’s as if we judge all prose by some throw-away kids book from 50 years ago. And incidentally, this is happening in a context where parents are increasingly pushing younger and younger kids towards ‘big-kid’ books.

Personally, I haven’t read comics in a long time. I enjoyed reading comic books as kid and would love to get back into reading comic books

Comics(reading and collecting) are definitely niche at this point but its nice to see a write up about the stigma I don’t know if I’ll ever get back into them.