Comics Code Authority: How censorship has affected the history of American comics

The Comics Code Authority (CCA) once ruled the comic book industry so that creators were restricted to follow certain guidelines when it came to writing their work. However, in 2011, the CCA officially went defunct considering comic book publishers were no longer adhering to the guidelines of an outdated comics code. Publishers were given the freedom to create content they desired to make.

Despite it no longer being around, the CCA played an influential role in the early days of the American comic book industry. It is time to go through the history of the CCA in order to see how influential it was during its reign.

Early 20th Century America

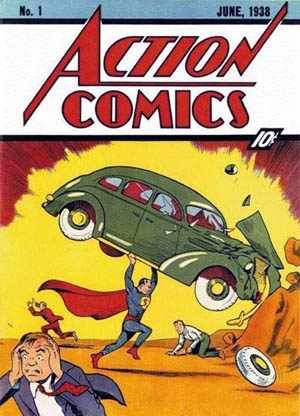

During the time of the Great Depression, when the American comic book industry was in its infancy, comic books were gaining notoriety from various parties who felt they were a threat to the youth. Educators objected to the publication of comic books claiming that they negatively impacted students’ education, primarily their reading and literacy skills.

During the time of the Great Depression, when the American comic book industry was in its infancy, comic books were gaining notoriety from various parties who felt they were a threat to the youth. Educators objected to the publication of comic books claiming that they negatively impacted students’ education, primarily their reading and literacy skills.

The fear at the time was that children were being exposed to content they should not have been investing time in; parents were scared their children were reading inappropriate material.

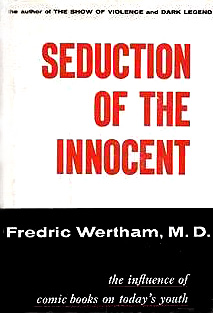

Other civic and church parties joined the protest, claiming that comic books were “immoral” due to the content they gave readers, such as nudity and acts of violence. The situation for comics book became wores when mental health experts began to participate in the discussion wanting to see comics banned permanently from distribution. One of these mental health experts was Dr. Fredric Wertham, who advocated for the complete annihilation of comics and the author of Seduction of the Innocent.

Wertham’s argument against comics was that they exposed children to violence and would cause them to desensitize violence itself. His arguments were based on evidence in what was being published in comics themselves. Seduction of the Innocent was thus written to discredit the comic book industry as a whole.

Seduction of the Innocent

Seduction of the Innocent was Wertham’s ultimate attack on the American comic book industry. The book came out in 1954 and detailed how “bad” comics were and how they were detrimentally impacting the youth of that era.

Seduction of the Innocent was Wertham’s ultimate attack on the American comic book industry. The book came out in 1954 and detailed how “bad” comics were and how they were detrimentally impacting the youth of that era.

Wertham’s argument against the comic book industry was built on his work in social psychiatry and his perception of how comic books were bad for children. He wanted there to be comic book legislation in order for comic book publishers to be restricted in the work they create; Wertham wanted comic book publishers to follow rules that would inhibit their ability to create “inappropriate” content. He would often present his findings at various events such as legislative hearings in order to make his case.

Eventually, the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency began an investigation, with hearings being held in April and June of that year where numerous witnesses testified to determine what the intentions of comics were. The investigation called forth many individuals who were working in the comic book industry in order for the court to hear their side of the story in the war between comics and the public. But while Wertham was conducting and showing the public his research, the CCA was forming, an entity consisting of the most prominent figures in the comic book industry to manage what was being published in comic books.

The First Casualty

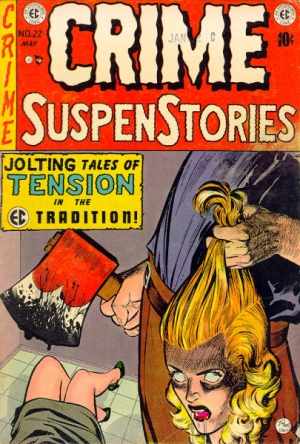

During the subcommittee’s investigation into comics, several parties in the comic book industry testified to give better insight into their works. One of the people who testified was William Gaines, the publisher of EC Comics.

During the subcommittee’s investigation into comics, several parties in the comic book industry testified to give better insight into their works. One of the people who testified was William Gaines, the publisher of EC Comics.

When Senator Estes Kefauver prompted Gaines during the testimony to offer an opinion on a comic book cover created by artist Johnny Craig featuring a severed head and bloody ax from the Crime SuspenStories series, Gaines said that cover was in “good taste.” Due to Gaines’ testimony, EC Comics shut down.

Because of EC Comics’ unfortunate demise, publishers banded together to form an entity that would help to oversee the comic books being published and called it the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA). The association created a regulatory code that highlighted what comic book publishers were and were not allowed to place in their work, which became the CCA.

The 1954 code had a list of rules that comic book publishers were supposed to abide by in order for their works to be approved. Some of the rules included never attacking religion and any indecent exposure of a character(s).

Gaines joined the CMAA after initially being hesitant to join. But Gaines’ tenure with the CMAA was brief, and he resigned in 1955 to start his MAD magazine business, which today is owned by DC Comics. But despite comic book publishers requiring themselves to abide by the CCA, some individuals wanted to defy the code to publish content that talked about real-world problems, with one being Stan Lee.

Stan Lee’s Defiance

Lee, the face of Marvel Comics and the voice of the comic book industry today, was asked to craft a story that touches on the subject of drug abuse. He published the story in Spider-Man, but unlike the majority of comics published in those days, Lee published the story without seeking approval from the CCA.

The story featured Spider-Man’s best friend Harry Osborn struggling with drug addiction and how it negatively impacted him. Lee thought it was a story worthy of publication as it delved into a real-world problem, showing how comic book characters are fictional manifestations of real world people and problems.

But while Lee published his work with Marvel due to his employment with them at the time, underground comics managed to find a way to slip out of the CCA’s radar. These comics bypassed the CCA through direct market distribution.

Due to Lee’s defiance, the CCA updated the code in 1971 to ease the restrictions on what could be published. The changes were the following: less restriction on crime comics and the ban lifted for horror comics.

Eventually, Lee’s defiance of the Code set a precedent for other comic book publishers to follow suit. Publishers realized that through direct market distribution, they could escape the CCA’s clutches.

The code was further updated in 1989 when DC Comics argued that the 1971 code was not needed during the time. The CMAA then drafted two documents based on DC Comics’ demands that then updated the code.

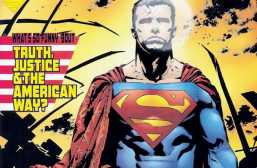

Today’s Comic Book Industry

In the years following the 1989 revision, the CCA slowly faded away. The 1989 code was the first to fade from existence.

Then, in 2001, Marvel Comics withdrew from the code and it and other publishers began to regulate their own comics, with the CCA eventually dying out in 2011. Essentially, the comic book industry no longer kneeled to a high authority. Since 2001, comic book publishers have been able to craft stories and more mature content for an audience consisting of both teens and adults.

These days, comic book publishers have become more liberal with the work they publish. Image Comics’ Spawn can kill people, Marvel Comics’ current Black Panther series uses real-world topics in a fictional setting, and DC Comics’ Midnighter and Apollo are a gay couple.

Publishers now have the ability to create the kind of work they have always wanted to create and do not have to fear any regulations from any code. No longer are they restricted to exclude characteristics that would be deemed “inappropriate.”

Some recommended readings are Spawn, The Private Eye, Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo’s Batman and Rick Remender’s Uncanny X-Force. These books demonstrate that comic book publishers have used their creative freedom to craft stories free from any rextrication and show how the comic book industry has evolved since the CCA faded from existence in the early 2000’s.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I think that no censorship leads to lazy writing and art. I think back to Disney’s Tarzan at the end when Clayton accidentally hangs himself. They COULD have shown all of it but why? To what end? If they didn’t have to adhere to certain rules the writers and artists might not have even thought to do a silhouette. The end result, a grim and haunting yet still tasteful image of a man killed by his own rage.

Comics and Retailers do need to institute a code. I’ve noticed that comics with cursing and nudity in them look just like comics without cursing and nudity. Kids in comic shops (although it’s rare to see ANYBODY in a comic shop nowadays) should have clear labeling that says ‘E’ for everyone or ‘M’ for mature so they can make better decisions and Shop owners should enforce those rules. I wouldn’t want my 10 year old kid reading “Sleeper”.

Say what you will. My favorite comics were printed with that stamp on the cover.

Fascinating! I admit I’ve never been interested in American comics, but this article is certainly worth a read. Informative and educational. Good work.

really liked it!!

The Comics Code Authority is survived by various ratings systems, the fading idea that the comics medium is wholly a subcategory of children’s entertainment, and a lingering sense of censoriousness in American popular culture.

I personally am a fan of media of any sort that airs on the side of caution when it comes to content. I would not presume to limit the freedom of creativity, but I would like to be informed what kinds of content are in media before I consume them; like the ratings of movies and TV. Being a dad, I know it is my responsibility, not the media’s, to monitor what my family is being exposed to. Having the content of media spelled out makes my job in that arena much easier!

I think comics writers should be creative and free.

It sounds like comics was in the same place as video games are today. Comics was a “kid” thing but not rverything was kid friendly. Like gta. Many think video games are for kids but some games are not for kids but many kids buy then anyway. I dont play video games that mutch but I think the next thing that kids start to like will be censured. In the 80s karate and horror movies was for grown ups but many kids watched it and got relly scared. Every generation have a thing like this.

I go with artistic freedom because yes it was fun how the golden and silver ages were but it just feels more realistic and most of the comics I read do show some blood and gore and stuff like that but it is not that bad I dont read any crime comics so I dont know how bad they are but still I ********************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************** THIS COMMENT HAS BEEN BLOCKED BY THE COMICS CODE AUTHORITY

A good artist will know that the human mind is capable of imagining things better (or worse depending on the situation) then a person could ever present in any visual form.

I wouldn’t mind and ESRB style rating system but I don’t necessarily think it’s anymore necessary than more censorship is(read: nor very necessary at all). But I do think we need more comics around that are targeted at younger readers because the entire industry has shifted to focus on teens and adults but little kids love comic book characters too(find me a kid who doesn’t know who Spider-Man, Batman, Iron Man and Superman are) and it would be great if there were more comics suitable for that age group. I’m talking super hero comics here, by the way.

Thanks for the great unbiased information! Good job!

The rating system we have in TV shows, Movies, and Video Games seems to work pretty well to an extent. We just need more parents to know what the symbols mean, so they don’t buy their 10 year olds Call of Duty. I think the same thing can be done with comic books. Let’s just use the game rating system as an example. Give Spider-Man an E for Everybody while restricting Deadpool to M for Mature. Both can be sold it’s just if a kid wants to get his/her hand on Merc with a mouth his/her parent would have to buy it for them. I think if rating systems go unnoticed they aren’t doing their job. That’s why when I worked at wal-mart I always told parent who were buy CoD what the rating system meant, and so then decided to buy their child something else. If we just ignore rating systems people will come against them, and say that they don’t matter. Thus they will try and get all of them censored. I don’t want my Mortal Kombat censored because you didn’t want to take the time to know what a few symbols meant. That being said I probably wont keep my kid from playing graphic games. It just depends on the game itself.

I think censorship can lead to some very interesting things. Take for instance if a hero wanted to curse but couldn’t. In that instance, the writer would need to come up with some way, which could end up being hilarious, for the hero to curse.

So basically comicbooks were video games of their day.

Only comics that passed a pre-publication review carried the seal.

I think slow but sure recognition of comic books as a sort of visual and artistic “mythology” has helped get rid of the idea of a censorship standard. Because that’s what comic books are, really – they’re myths and legends interconnecting and entwining the same way ancient lore has for centuries. Marvel and DC are omnipresent in every day life. It’s fantastic marketing, really.

a rating system is better than complete censorship 10 times out of 10

I believe that it would be a good idea for comics to have some sort of sign that says if they are acceptable for children or not. Marvel and DC always target children in some way. Animated series, movies which are sometimes a little too childfriendly (looking at you Marvel) and action figures yet their comics aren’t known to be childfriendly. I think that they should make some comicbooktitles targeted at children, sort of like the DC animated universe comics.

Wouldn’t it be hilarious if someone created a comic that broke every single rule in the old Comic Code? Even extending to the rules they have for advertising? It would be completely obscene and ridiculous but it could be an entertaining creative experiment.

It does exist. It’s Called Deadpool.

The code became a topic of joking and derision among a new generation of creators who delighted in seeing what they could sneak past the censors.

Very informative and well-researched article.

Thanks for giving us one more reason to love Stan Lee!

i’m against censorship of any kind, i believe people can auto regulate if they are given a chance. creative freedom should be a must in any kind of art, comic books are a type of art (two of fine arts in fact).

Should Comic books be Censored? No. Not ever. Not one word. Not one image. Not one idea. Should Comic books have ratings guides like TV shows, Movies and Video games? Yes. Like any media, the content is for various age groups ranging from young children to adults and parents should have a ratings system built up on a commonly accepted set of guidelines they can understand and use in their own judgement as to determine if they wish their child to read the material at their current age. But I also think regular books should get the same ratings system the very same day the Comic books do. Just like I want to have nutritional and ingredient labels on food before I purchase it to feed my kid, I would like to know what is in a Comic book or book before buying it for my child.

Very interesting. Not something I’d even really thought about. I guess comics became an adult medium so gradually that we sort of forget it was always intended for children. I agree with a classification stamp on the front. Great idea.

A rating system would at lest help parents see what may or may not be good for their children.

I don’t think the Comics Code should be around but they should have ratings, like little kids should read Batman Endgame or Death of the Family

The have finally blinked out of existence! 56 years old. 😉

Censorship is a bit of a double-edged sword. On the one hand, yes I can see how restrictions breed creativity. It can force creators to be smarter in communicating their message and it can challenge audiences to think deeper about the media they’re consuming.

If I’m remembering correctly, Batwoman was created to disavow Batman and Robin’s seemingly ‘gay’ relationship-either due to censorship, or just reception. Some poetic justice: the current Batwoman is DC’s #1 lesbian character.

(A continuation on gay characters: the 2015 Midnighter miniseries is really good; if anyone’s interested)

It’s interesting to consider that under the CCA comics sold almost twice as much as they do today (even after the terrible crash in the 90s). I don’t think it was because the CCA was good for business but I think the prevailing notion that comics were meant to tell good stories and as tools for indoctrination definitely helped move copies.

Another element that played into this was the necessity for authors and writers to be creTive with their stories. Superhero comics are inherently violent and with the code in place, it become important to utilize the comics form in innovative ways. Take Frank Miller’s Wolverine run for instance. Even in the late-code era it wasn’t ok to show a bad guy getting SNIKTed in the face, yet it could be implied by combining the gutter with creative artistry forcing the reader to “imagine” the violence. That doesn’t happen as much now… shame.

For those looking to continue their reading on the subject, Amy Nyberg’s Seal of Approval: the History of the Comics Cose Authority is great and very enlightening!

Did the Code squelch social commentary on issues such as racism?

I enjoyed this article. I knew nothing of Wertham, I’ll have to find a copy of his book.

Further proof that censorship stifles ideas, and spreads misunderstandings between creators and consumers. I often wonder how many works were lost during the mass burnings.

A decent write up about one of the more unfortunate chapters in comic book history. Good work.