Don McCullin: Horrific Humanity Through Photography

Don McCullin’s willingness to photograph the aftermaths of catastrophic events shows his powerful presence as a photographer. “When I went to war, I didn’t need any tuition. I’d been in the bombing since I was a child”. McCullin’s admission of his familiarity with catastrophic events such as growing up during the London Blitz gave him precedence to capture horrific consequences upon humanity. McCullin’s photography has placed him in a conflicted situation. In retrospect, McCullin stated, “I actually don’t believe I’ve changed anything at all. On many occasions I’m ashamed of humanity”. This admission marks a definitive motif in McCullin’s photography, feeling his work was not significant in changing an event’s outlook. McCullin merely wished to expose horrific realities of sorrow and destruction.

McCullin’s ability to capture catastrophic moments in a direct and bold manner evokes these moments of sorrow and destruction. McCullin’s audience at the very least should understand the experiences of his subjects, condemning the brutality of catastrophes, destruction of humanity, antagonising pain and sense of loss involved. If McCullin’s photography could changed perceptions then his photographs are significant.

Humanity as Sorrow in McCullin’s Photography

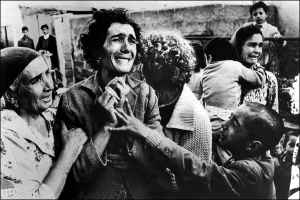

McCullin photographing humanity as sorrow helped antagonise violence whilst empathising with the affected subjects. It refers back to McCullin’s shame for humanity, where it has been tainted by catastrophic events such as war. He first covered war within inter-communal violence between Greek and Turkish Cypriots in Cyprus. As inter-communal violence is fought between neighboring communities, Greek and Turkish Cypriots’ lives were frequented by brutal violence. Therefore it was inevitable McCullin’s photography would capture sorrow caused by war. The photograph Turkish Cypriot Woman Mourning (1964) is harrowing. The composition’s emotive core is centered on the grieving woman. The expressions of consuming grief and utter despair painfully depicted on her face and body language creates instantaneous feelings of sorrow and destruction. Surrounding her is an equally emotional young boy sharing the woman’s grief and an older woman attempting to console her. The environment McCullin captured reflects common aspects of brutal violence and death within the subject’s lives reaching its unfortunate fruition.

The inter-communal violence between Greek and Turkish Cypriots in Cyprus was similar to close quarter fighting between Israelis and Palestinians because it also resulted in brutal violence and death. Again, McCullin’s shame for humanity gave him the ability to make his audience understand the devastating grief and sadness endured by those left behind. In the photograph Grieving Palestinian Family (1976), the composition allows audiences to understand every subject’s emotions. Understanding the women’s uncontrollable grief and the men’s futile yet whole-hearted attempt to console them helps to grasp their situation. Grieving Palestinian Family embodies the situation by accumulating expressions of pain, anger, and despair which led this Palestinian family to have their humanity destroyed. McCullin’s audience can share his shame in humanity by seeing such anguish upon victims of violence.

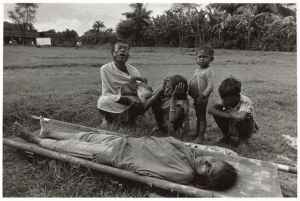

McCullin capturing humanities’ sorrow also applied towards natural disasters. Whereas McCullin had stated his shame of humanity, he could also empathise with humanity. McCullin noted, “If you can’t feel what you’re looking at, then you’re never going to get others to feel anything when they look at your pictures”. This is important to note as McCullin wanted his audience to fully understand each situation. McCullin continued to reflect his stance on humanity in sorrowful scenes such as Misery of West Bengal Family (1971). McCullin focused the composition upon the dead Mother’s body, the photograph’s most powerful aspect. In doing so McCullin’s audience can understand the situation’s reality leading to the other subject’s emotions. They were in stages of mourning, particularly the Father and Daughter animated in grief whilst a younger son looks directly into the camera with a confused sense of sadness. Misery of West Bengal‘s intimacy emphasised McCullin’s aim to convey feeling, therefore understanding humanities’ sorrow.

Humanity as Destructive in McCullin’s Photography

Humanity as destructive represents individuals who have become soulless or deeply affected by violence. McCullin regarded destructive aspects within humanity as “if you’re in battle in Vietnam, watching young men dying and trying to kill other men, and there’s no truth in that, where is there truth?”. McCullin felt there was a truth within situations where humanity becomes destructive which had to be documented. Shell-Shocked U.S. Marine (1968) is arguably McCullin’s most famous war photograph as it conveyed the U.S. Marine’s humanity after its destruction. The composition isolating the U.S. Marine from his environment enhances understanding of destructive humanity as audiences can contextualise the extent in which he was affected. His eyes conveyed the infamous thousand-yard stare immediately telling McCullin’s audience how war had broken his humanity, becoming lost within himself. The U.S. Marine clutching his rifle was a desperate attempt to protect himself from immediate danger. The U.S. Marine’s tense body language embodied humanity as destructive in times of war.

McCullin’s photojournalism coverage of the Lebanon Civil War, where Christians fought Palestinians in secular violence continued to show humanity as destructive. Phalangists with the body of a Palestinian girl (1976) contained a lack of humanity as a group of Christians celebrated near the body of their victim. The composition of Phalangists with the body of a Palestinian girl with the victim’s body in the foreground makes McCullin’s audience immediately confront the tragedy of her death. This continues looking upon the group of Christians particularly the boy with the rifle (presumingly her killer) staring at her body in a sadistic manner, as if he feels empowered by his actions. The two boys in center celebrating along with the remaining friends are equally disturbing, looking relaxed despite their recent actions. McCullin may have felt unable to contribute towards the course of events yet he offered a capability for his audience to understand and expand their knowledge upon catastrophic events.

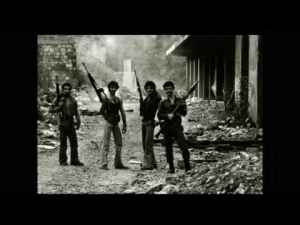

Armed Phalangists (1976) was another example of McCullin’s photography continuing to reflect individuals who had lost their humanity. In the photograph a group of armed men posed in wake of their carnage. Every person conveyed themselves with a high sense of confidence and narcissistic self-worth. The composition helps reflect the unapologetic attitude within every member of the armed group for their carnage. The contrast between their pride and the surroundings within context of McCullin’s photo-journalistic aims notes his portrayal of humanity as shameful, which McCullin’s audience could also understand.

McCullin’s photography in capturing catastrophic events (mostly war) did have the capability to evoke his audience. McCullin describing himself as a person associated with catastrophe meant he could convey humanity through sorrow and destruction. McCullin’s photography evidently resulted in his audience understanding McCullin’s intentions. His photographs condemn the brutality of catastrophes through conveying humanities’ destruction, wanting audiences to sympathise with the antagonising pain and sense of loss experienced. McCullin made his audience feel his shame of humanity resulted in understanding the horrific catastrophes McCullin’s subjects went through.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

fabulous man, fabulous photography

Very powerful & profound! Everyone should be aware of Don McCullin work.

Thank you Ryan for your article regarding the photographer Don McCullin. Artists that document the humanity and inhumanity gives us the opportunity to reflect and engage in our actions. Capturing these moments make us mindful of the humility we as humans are capable of inflicting upon each other.

Thanks for your comment. I do agree that those who capture moments McCullin did in his photography help audiences realise their own humility.

Thank you for this fantastic look at McCullin’s photography and philosophy. McCullin’s admission that he doesn’t feel he’s changed humanity for the better is a powerful one and it certainly compels you to view his work with a deeper sense of clarity. The power of his work is compounded when remembering that he feels great shame in humanity’s penchant for destruction.

As I look at the photos you’ve chosen for your article, I am impressed with the sparseness of McCullin’s work. Several of the pictures remind me that once the veneer and myth of war is stripped away, what you see are the faces that reveal more than words could ever hope to.

Thanks again, Ryan, for a compelling article.

Thanks for your comment Jesse. McCullin’s photography certainly does identify the horrific emotions inflicted on victims of war.

Fascination, inspirational. Thank you.

His photography is stunning, on so many levels…

It’s so wonderful to see that, even at his age, he quickly understands and grasps the power of digital photography.

Incredibly powerful. Thank you for sharing.

I can comprehend the shame, the utter distress felt by McCullin in his perceived fruitless hope for humanity. I feel that having been so emerged in catastrophe it makes it hard to see more than the lament illustrated in his photography. I still have hope, even staring the brutality he captures in the face I have hope. All of these images show me one clear thing; we all bleed, we all cry. Even in our misguided nationalism and religious fervor all these poor souls were doing the shameful things they thought would make their lives, and the lives of their loved ones better not taking the time to understand that they are the same as their enemies.

If these photos are taken out of context, and shown in isolation to those who committed these crimes they can’t hide their empathy behind some self serving facade. Humanity is selfish, and misguided. If we could abandon our pride, those who do nothing but take could see they are the same as those they’ve taken from. It is a far off dream, but I hope it is a lesson humanity learns one day. I think McCullin’s photos open the eyes of his audience more than he credits.

I feel so bad for not knowing about such a person… Hats off.

Don McCullin’s photography is extremely powerful. HIs photographs have the ability to make you rethink the world we live in. I believe that photographs can be more powerful than video or any other form of media in capturing emotion. McCullin’s photographs catch your attention and pull emotions out of you. When you feel emotion when looking at a picture you know that the photographer has done his job and in this case McCullin has achieved this.

I believe I’ve seen the Vietnam photograph before. Nice to know where (McCullin) it came from.