Fantasy Writing and Classical Antiquity

Fantastic Inspiration: Here be Dragons!

Fantasy writers often are aware of the behemoth of history that they sit upon. To write in fantasy is to contribute to a tradition that has roots in the very beginning of language itself. An exploration of the origins of fantasy can offer a writer new ways to reflect on the inherent archetypes and narratives at play in their own work. To begin: first there were the fantastic stories from Classical Antiquity (1000 BCE to 500 AD).

Fantasy has a beginning that is difficult to pinpoint. It has roots that reach back to the time of oral traditions for at its base are the myths and legends that form most of early literature, ergo there is no simple starting point. When the topic of fantasy arises it is often children’s literature that the mind turns to: fantastic tales of heroes and gods battling in Greek-sounding places; of worlds populated by talking beasts and wee fairies who grant wishes; or to the more recent stories of a boy hero with a lightning scar. However, fantasy had a more “adult” beginning. Although still drawing on mythological and allegorical sources and styles, fantasy literature told tales that aimed to guide, inform and entertain a range of listeners/readers. Equally, the source for the word fantasy is not easy to simplify and point to. Rather the word, like the literature that has come to belong under it, had a fluid, transformative journey through time. It is not the intention of this article to provide a comprehensive investigation of all texts that fantasy draws its history from. Rather it aims to provide a brief context to understand better the roots from which the tree of modern fantasy has grown.

It is from this history that fantasy writers today can draw inspiration.

This article aims to look briefly at the period of Classical Antiquity, a huge period, and in no manner do I suggest this overview is comprehensive. Rather it is synoptic and draws attention to the forms that are still present in modern fantasy. It should be noted here that the subheadings, as also the general overall discussion, relates primarily to European literature and Western fantasy, this is largely due to my own personal context and studies in Western Literature and the Fantastic. At a later stage it would be important to examine how other mythologies also influence fantasy literature.

The influence of Classical Antiquity on Contemporary Fantasy

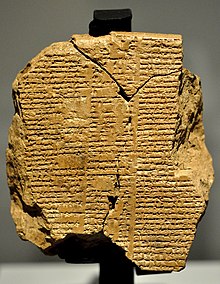

The fantastic elements present in the early Greek epics are important aspects of modern fantasy 1, both the storytelling structural elements and the supernatural-otherworldly presences. There are few critics of the fantastic that do not draw a parallel to ancient literature, Dennis Kratz in ‘Development of the Fantastic Tradition through to 1811’ began by stating: ‘The literary tradition of the Western World begins with the Greeks, and classical Greek literature, from Homeric epic on, is essentially fantastic. The fabulous nature of Greek literature derives primarily from the practice, initiated by the bards who created the epic tradition, of drawing their artistic subjects from the realm of mythology.’ 2 Yet, even earlier than the Greek bards, is the Epic of Gilgamesh (c 2100 BC), an epic poem written in the main Semitic language of ancient Babylonia and Assyria that portrays the adventures of a king. Gilgamesh begins the tale as a tyrant whose own people call to the gods for help, the gods send Enkidu whom Gilgamesh battles and eventually befriends. The tale includes a number of recognisable fantastic elements – the presence of gods, supernatural powers, mythical creatures – all of which continue to appear in modern fantasy.

Lucie Armitt suggested that ‘The relationship between the real and the unreal during the classical period was far more fluid than our own rather prosaic determination to assert reality at all costs. We may well attach much of the strength of fantasy in the writings to the ancients to the fact that mythology was, during that time wrestling with the ideas that may have appeared monstrous in scale.’ 3 Arguably, the same appeal remains in the continuing popularity of fantasy, we may no longer be seeking answers to natural phenomena, but the larger questions on the purpose of life still remain unanswered and monstrous in scale. The modern reader is less inclined to believe in the fantastic elements of a story, yet this does not diminish the appeal of such stories. Contemporary fantasy continues to draw on sources from ancient mythologies for this reason, because the particular mythopoeic creations of this period are still symbolically relevant for today’s reader. The desire for a leader to be just and honest, to search for help from a higher power, to desire immortality, all of these longings are as relevant to people today as they must have been to the listeners of the Gilgamesh epics.

The Epics of Homer

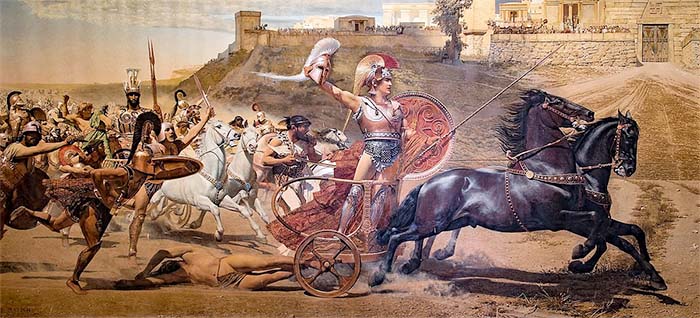

The epics of Homer (c 750 BC) of the Iliad and Odyssey each contain the traditional hero’s journey that most High fantasy is also structured around. Yet the tales are not simply the trials of men travelling across ancient lands, the beauty and power of the tales is in their heroes brushing against elements not considered “real” or “natural”. Achilles chose a life of adventure and war in a pursuit of glory. He faces not merely men, but also a number of interference by the gods as a range of the pantheon appear to guide or influence outcomes of the Trojan War. In the Odyssey Homer’s epic journey has him encountering a plethora of creatures: cyclops, sirens, nymphs, naiads, as well as gods and other lesser creatures.

The Homeric epics are fantastic texts, yet each deals fundamentally with the human experience, John Scott in Homer and His Influence and Jacqueline De Romilly in A Short History of Greek Literature both emphasise that because of the particular perception by the Greeks of their gods and heroes these epic tales are stories about humanity. ‘Perhaps the first characteristic of the Homeric world to strike the reader is the unique way it brings together men and gods,’ the gods of these tales are not unknowable entities, but rather the ‘poet imagines their relations with one another as those that might exist in a small human kingdom.’

When Zeus deliberates on the Trojan war he is joined by other gods, ‘Now the gods at the side of Zeus were sitting in council’ (Homer Iliad 1974: IV 1), and he is not the only power, ‘So he spoke; and Athene and Hera muttered, since they were/ sitting close to each other, devising evil for the Trojans’ (IV 20-21). The gods are seen as influential, but also as petty and jealous as mortals, since ‘the Homeric gods are not merely anthropomorphic but “human” in the extreme, with all the failings the word implies. Yet they are also radically different from men, for they are immortal and enjoy superhuman powers.’

Heroes, too, are not free from humanity, ‘Into the story of Achilles’ anger’ the poet has woven most of the great human emotions and has endowed all his actions with an individuality that has never been surpassed.’ The heroes of the Greek epics are closest in the development of fantasy to modern heroes, where Medieval and Renaissance heroes became flawless and motivated only be faith and goodness. The ancient heroes were flawed in much the same way the post-Tolkien heroes have become. Contemporary fantasy draws heavily on these ideas in both that the supernatural creatures that are as internally weak as humans, and that the protagonists who are ordinary humans with some form of divinity in extraordinary situations that help define them as heroes. De Romilly made an interesting point on the importance of this relationship between gods and men that can be examined equally as the relationship UF also purports as important:

But it is important to realise that for the Homeric hero the existence of the gods makes a difference to every aspect of life. It inspires fear; it also inspires confidence. In particular, it gives human life distinctive contours and reveals it in a distinctive light. The extraordinary closeness it establishes between god and mortals has the effect of elevating man to an unusual eminence, rarely matched in later ages; while the cheerful familiarity with which the gods are mentioned reveals a human delight in, and love for, this life where the divine is everywhere. At the same time, the constant reminder that these superior powers exist implies a kind of pity for man. The two perspectives are compatible because the hero himself accepts the limits of his existence.

De Romilly

Low Fantasy (fantasy not set in an epic secondary world), unlike typical Secondary World narratives, presents a mundane world immersed in supernatural presence. Although the characters at times bemoan the presence of such, they ultimately are empowered and defined by that presence. A number of protagonists become fixated on their humanity, a realisation that would not have occurred without the contrast of the inhuman. Furthermore, they are more aware than others of the role these creatures play in their world, which does evoke fear. Yet they become empowered by this also so that they are able to fight against, with or among, such inhuman powers.

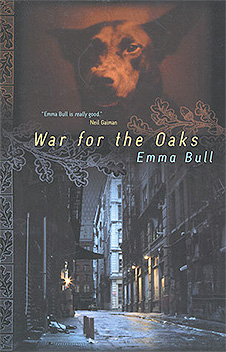

In the seminal urban fantasy novel, War for the Oaks, Emma Bull wrote of her protagonist Eddi: ‘Anger and fear were scrambled in Eddi’s head. When she spoke, she didn’t know which emotion it was from. “When Faerie and my world intersect, does anything good ever come of it?”’ Yet when Eddi faces her enemies she has become inspired by the importance of fighting for more than mere survival: ‘Here in this room was what she fought for, this wild human energy, this fast-burning mortality that made so much light.’

In a similar manner renowned author Mercedes Lackey’s character Diana in her Diana Tregarde Series is aware of the responsibilities she must shoulder because of her understanding of the dangers that supernatural creatures pose: ‘She was all there was; she and Mark were all that were standing between a city full of innocents and something a major Power feared enough to warn her against.’ The protagonists of such low fantasy are not naïve heroes; when they finally face their final battles they understand the stakes and their roles, as well as the consequences if they fail.

The heroes of contemporary fantasy are defined by their relationship with the supernatural; they are heroes because of the supernatural presence in their lives, not always because of some unique inner quality. In the Iliad Achilles was one of many demi-gods, ‘These were the strongest generation of earth-born mortals,/ the strongest, and they fought against the strongest, the beast men/ living within mountain, and terribly they destroyed them’ (I 266-8); while Odysseus was a godly king, ‘All the gods pitied him,/Except Poseidon, who contended unremittingly/ With godlike Odysseus, till the man reached his own land’ (The Odyssey I 19-21). Both are distinguished from other mortals by their heritage, yet the adventures they undertake are defined more fully by their own mortal nature and their interactions with the gods. Their strength may outweigh that of other mortals, yet pales in the presence of the supernatural creatures they face. Their determination to still face these battles and the humanity they express as they do so is what makes their characters so fascinating.

Vigil’s Aeneid

These ancient epic poems examined more than the mythologies of a people, but were concerned with the stories of the actual people. Virgil, writing later in Rome composed the epic Aeneid (c29-19 BC), a poem concerned with the spiritual journey. As R.M. Ogilvie in Roman Literature and Society presented, ‘In the first place Aeneas is a hero in search of his soul. The Aeneid is very much of a spiritual quest, which makes it unique in ancient literature. Only Virgil admits of the possibility that a character can change, grow and develop.’ Aeneid follows the journey of Aeneas in his effort to found a new city in the West, Rome, and fulfil the destiny placed upon him by the gods. 4

It shares a number of qualities with the Homeric forms of adventure and divinity, but also ‘we see the heroic bravery, the rash impulses of the Homeric warrior set against the specially Roman qualities of family life, social virtues, deep religious piety.’ What the Aeneid offers is an insight to how the same heroic qualities present in Homeric verse can be reinterpreted through the lens of a different culture and period. In much the same way as modern fantasy has reimagined the hero’s journey and the experience of divinity. In David West’s introduction to his translation of The Aeneid he wrote:

The Aeneid is still read and still resonates because it is a great poem. Part of its relevance to us is that it is the story of a human being who knew defeat and dispossession, love and the loss of love, whose life was ruled by his sense of duty to his gods, his people and his family, particularly to his beloved son Ascanius. But it was a hard duty and he sometimes wearied in it. He knew about war and hatred and the waste and ugliness of it, but fought, when he had to fight, with hatred and passion. At the end of twentieth century the world is full of such people. While we are of them and feel for them we shall find something in the Aeneid. The gods have changed, but for men there is not much difference.

Aeneid vii-viii

This is not to imply that all contemporary fantasy is on the same level as the classics for the quality of exploring the human condition. It is difficult to produce the intensity of emotion that verse and a purely heroic epic can allow, yet they aim to explore the same ideas. Characters especially those who are immortal are able to explore the ideas of loss and hardship, of duty and passion in a manner not as easily developed in realist novels. The element of fantasy lends itself to being able to express these huge emotional concepts in a way that is still accessible.

Apuleius’ The Golden Ass

Then as the Roman Empire reached out to new lands across the Mediterranean a move towards prose fiction as the more common form of literary entertainment occurred. A text with strong fantasy elements is Lucius Apuleius’ late Latin prose The Golden Ass (c 180 AD) in which Lucius, a traveller, is accidentally transformed into an ass when he is tempted by a witch, both the presence of mystics, or witches, and transmogrification are common tropes in fantasy now. Apuleius as an outsider (born in what is now Algeria) to the Roman traditions manages to create a tale quite critical of the beliefs of his time, it can be argued that in fact it was his ‘aim to expose the hollow frauds and immoral tendencies of the popular superstition of his day.’

Yet, it is also equally valid to consider that he merely reflected the cultural curiosity concerning the supernatural, not an unusual situation. It was an age of interest in natural and supernatural phenomena and that ‘despite all the conventional fairy-tale elements, one begins uncomfortably to feel that a good deal is derived from the travels and experiences of Apuleius himself as a young man.’

Whatever the view it is difficult to ignore what Apuleius has offered to the modern novel, as Charles Whibley in his opening essay to a translation of the text stated, ‘“The Golden Ass” of Apuleius is, so to say, a beginning of modern literature.’ A bold statement, yet as it is one of the earliest prose texts dealing with a fictional framework it is easy to see how The Golden Ass can be seen as the forerunner for the modern novel. Whibley pointed out ‘From this brilliant medley of reality and romance, of wit and pathos, of fantasy and observation, was born that new art, complex in thought, various in expression, which gives a semblance of frigidity to perfection itself.’

It is a tale of humour and fantastic foolishness, yet at its heart it deals with an introspective examination of the idea of human transformation. Not through magic, but simply in the changes of self, centred on different situations. The opening to Book One begins in fact as such: ‘Stories of men’s forms and fortunes transformed into different shapes, and then restored again in due sequence back into their selves – a true subject for wonder’ (21). An opening that could relate to the transformation of Lucius into an ass, but also of the transformations of people’s characters when faced by adversity. Yet a reader cannot help but being captivated by the ever-present elements of fantasy.

The journey of Lucius both before and after his transformation is fraught with the tales of magic and the supernatural, though interestingly not of the presence and interference of gods as other literature had focused on. In many ways Apuleius’ story belongs more to folk-lore and fairy-tale than mythology. Although, Apuleius does include in Book V the tale of Cupid and Psyche, as overheard by Lucius in the form of an ass, a story whose form is well known in later tales: ‘This elaborate story of the “Fairy Bridegroom” contains many features of folk-lore which reappear, as is the mysterious habit of folk-lore, in the tales of widely separated lands.’ However, the predominant form of fantasy is that of magic and transformation. Whibley pointed out the constant and important presence of sorcery in The Golden Ass:

So there is scarce a scene without its ghostly enchantment, its supernatural intervention. And herein you may detect the personal predilection of Apuleius. The infinite curiosity where with Lucius pries into witchcraft and sorcery was shared by his author. The hero transformed suffered his many and grievous buffetings because he always coveted an understanding of wizardry and spells; and Apuleius, in an age devoted to mysticism, was notorious for a magic-monger.

Whibley

The fascination with magic as a form of transformation is rife throughout: ‘Thus by her sorcery she transformed her body into what shape she would’ (76); ‘to turn again the figures of such as are transformed into the shapes of men’ (77); ‘these witches do change their skin and turn themselves at will into sundry kinds of beasts’ (55). There are other supernatural tales, but transformation is the strongest theme throughout the tales, both supernatural and human. Transformation is a strong trope in many fantasy novels. In fantasy it is actually of more importance than the traditional magical alteration of human to animal, rather it is centred on the protagonist’s change from human to other, either by nature or by situation.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses

An excellent source for mythology is Ovid’s Metamorphoses (17 AD), an epic poem chronicling the “history of the world” and includes material that appears in the later works of Chaucer, Dante and ‘Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queen (1590-6) is steeped in Ovid. Moreover, the influence of the Metamorphoses on Shakespeare himself is again so pervasive that it deserves a book of itself.’ Ovid’s work is invaluable to the fantasy genre as his work is one of the most common sources for the Renaissance, English Elizabethan Age and modern fantasy, largely because of the treatment of the subjects. It is clear in the tone and framing of the verse that Ovid was strongly drawn to the tales he wrote and his ‘vivacious imagination, and preoccupation with love and the supernatural’ still draw readers back to his work.

In summary, Metamorphoses is the collection of tales of magical shape changing of human to animal, plant or even mineral, a theme frequent in the earlier works previously discussed. Ovid in fact opens with a clear reference to this: ‘Of bodies changed to other forms I tell’ (Ovid, transl. Melville, I 1). The language is superb and the transformations capture the imagination, for example from the tale of Phaethon, ‘And Phaethon, flames ravaging his auburn hair,/ Falls headlong down, a streaming trail of light,/ As sometimes through the cloudless vault of night/ A star, though never falling, seems to fall’ (II 319-22). This style of transformation is favoured in many later fantasy novels where the beauty is not in the human or animal form, as lovely as that may be, but in the magical transition between states. In War for the Oaks the phouka changes from man to dog, ‘There was a sparkling whirl of air around him that seemed to dissolve him, and with it a fleeting fragrance of warm earth and fresh water’ (Bull 49), using this traditional mythical imagery. Even the more direct of Ovid’s changes hold a strange beauty, ‘One, in dismay, felt wood encase/ Her shins and one her arms became long boughs’ (II 352-3) and ‘His mouth became a blunt unpointed beak./ He was a strange new bird, a swan’ (II 375-6), and are mimicked in many contemporary fantasy novels.

It is certain that many of these stories and components have contemporary equivalents. Fantasy as a genre is backwards looking and often borrows from a breath of mythology, however, it is useful to understand the context and focuses of the different eras of fantasy’s own history. A contemporary fantasy writer will often find it useful to draw from recognised sources, as such sources are already part of a larger social consciousness milieu. Finding ways to reinterpret these themes, topics and creatures is what allows a new author to breathe life into older tales, and to add in their own unique way to the vast tapestry that is the fantasy genre.

Works Cited

- Pringle, David Ed. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London: Carlton Books Ltd., 1998 ↩

- Kratz, Dennis. Fantasy Literture: A Reader’s Guide, New York: Garland Publishing, 1990 ↩

- Armitt, Lucie. Fantasy Fiction: An Introduction. New York: The Continuum, 2005 ↩

- Williams, David. ‘Wilgefertis, Patron Saint of Monsters, and the Sacred Language of the Grotesque’. Ed. Robert A. Collins and Howard D. Pearce. The Scope of the Fantastic – Culture, Biography, Themes, Children’s Literature: Selected Essays from the First International Conference on the Fantastic in Literature and Film. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1985. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Beautiful article. I had never considered the relationship between fantasy and antiquity before.

What a lovely writeup. Are there any books you would recommend for further reading?

The Evolution of Modern Fantasy by Jamie Williamson is a really interesting study of the roots of the genre, starting with early Romanticism and Gothic lit in the 18th century all the way to the mid-20th century.

Partners in Wonder: Women and the Birth of Science Fiction, 1926-1965 by Eric Leif Davin (there is some overlap with fantasy in this, and some of the writers were writing in both genres by today’s definitions). Also useful for how it looks at early readers and conventions. Some grains of salt are needed for certain sections IMO because I disagree with his conclusions, but the data is solid.

John Clute, an SFF reviewer / editor / essayist, back in the 90s wrote The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, which he later followed up with The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. They’re both pretty hefty tomes. I’ve got the original hardbacks sitting on my bookshelf.

Brian Aldiss’ The Trillion Year Spree. Wonderful book that looks at the history of sf and fantasy. Erudite and opinionated (and Anglocentric). Expect to disagree.

Fantasy is immense.

This is a really interesting article and topic. Fantasy is the oldest genre in the world because the earliest written works of fictions we have are full of fantastical elements. The Epic of Gilgamesh, Homer’s The Odyssey and probably many tales that existed in the Oral Tradition. Fantastical elements never went away either.

Modern fantasy novels are just too long. Ever since Tolkien hit the big time, every author thinks they need to bring out a bloated multi-volume saga with maps in the back. It wearies me just to look at them.

I love maps.

How can any article on fantasy fiction not contain any references to Edward Plunkett (Lord Dunsany)? He was writing 30+ years before the vastly overrated Tolkien.

Doesn’t appear to be the aim of the article to include the entire history of Fantasy.

I loved that music is a big part of War for the Oaks.

Yeah. I liked the description of how the crowd and musicians feed off each other.

I believe Beowulf is accepted as the first example of something similar to modern fantasy. However, myths and stories which are ultimately a fantasy are as old as humans.

I found this book terribly boring. Eddit is dragged into a fairy war. Woopie, another world being taken over scenario. But personally? I did not care about it.

From the very beginning of English Literature Fantasy has been its overreaching theme.

If we compare with Spanish Literature, the very first work of English Literature is the Beowulf, a total fantasy of the Getas -that is, the Goths.

The very first work of Spanish Literature is The Lay of Myo Çid -absolutely realistic, Ruy Díaz cries looking at the empty nests of his hunting birds, finds locked doors at the inn, a little girl begs him to go on his way or the citizens of Burgos will be punished by the king, and so on.

This pattern goes on through the centuries, Sir Gawain compare that with Lazarillo de Tormes, Shakespeare many of his works are pure fantasy or have strong fantastical elements -A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Tempest, Hamlet and the Ghost, Macbeth too- Lope de Vega in Spain was absolutely a realist author and Don Quixote by Cervantes is an attack on the fantastic tales of chivalry of northern Europe.

That continues, there’s nothing like Lewis Carrol in the literature in Spanish, except perhaps for Borges and he was an aspirational Argentinian who wanted to be an Englishman -and some tales by Cortázar.

Right now the Spanish Literature is so realistic we have a derisive word for it: Literatura Garbancera, that is, of the chickpea pot.

I agree. In general I find contemporary Euro-lit to be much more indebted to realism than American lit. Although, I’ve also loved Unamuno’s interpretation of Don Quijote as being an idealist trapped in a world that doesn’t understand him.

I always thought that all fiction was fantasy. Because it is made up. Some authors are wierd and write about murder or romance over and over again in their narrow genres. They are stuck in a rut because they want to make their stories seem real. If you are going to make up a story and stretch your imagination – you might as well go all the way and do something….FANTASTIC!

It is likely fantasy is as old as humanity itself.

Maybe as old as the written language, but humanity is 250k years old at this point (by some estimates). The Sumerians only started writing between 4k-5k years ago.

Thanks for delving deeper into this specific genre. I’ve learned a lot!

Should you all wish to delve outside of heroic fantasy, I would recommend Hope Mirrlees’s Lud-in-the-Mist as a seminal urban fantasy.

What’s remarkable about today’s Fantasy is the depth and breadth of the talent it’s attracting.

There is an amazing variety of really great writers working today:

Mark Lawrence, Peter V. Brett, Scott Lynch, Brett Weeks, Brian McClellan, Joe Abercrombie, Adrian Tchaikovsky, Pierre Pevel, Markus Heitz, Andrzej Sapkowski, R. Scott Baker, Paul Witcover, Gene Wolfe, Django Wexler, Jen Williams, Helene Wecker…

I could really list a couple hundred top notch (or more), amazingly good, living and working Fantasy authors. The field has never been more powerful and vibrant than any time in its history. We’re in the firs true Golden Age of Fantasy. As a reader, it’s a wonderful time to be reading!

This makes it clear that Shakespeare was late to the party by a few thousand years.

I’m trying to think of a cut off point for ‘modern fantasy’ (whatever that means). Tolkien was certainly influential in defining the core tropes of the genre (secondary world, non-human civilisations, wizards etc) but he drew influence from writers such as Lord Dunsany, who wrote Gods of Pegana and The King of Elfland’s Daughter in the early 20th century. Dunsany himself drew influence from a variety of sources, including the Bible and Greek myth.

If we go back further, into the Victorian age, we have works like A Christmas Carol, Gulliver’s Travels and Paradise Lost, all distinctly fantasy stories who’s themes and ideas still hold true today.

Going further back, we have Shakespeare, who wrote several fantasy plays—most notably Macbeth, A Midsummer’s Night Dream and The Tempest.

Before Shakespeare, in the early mediaeval period, Arthurian legends were very popular, and many of them had supernatural elements to them—Excalibur, Merlin, the Green Knight. This style of writing was parodied in Don Quixote.

Before Arthur was Beowulf, the Hero King who slew trolls and giants. Tolkien’s The Hobbit is almost the same story, except instead of a brave warrior the main character is a reluctant thief.

So that’s at least a 1500 years of fantasy writing there, and I’ve only mentioned British stories (okay, some of the Arthur stuff was French (looking at you, Lancelot) and Beowulf, whilst written in Old English, is set in Denmark, but the point stands that it’s part of Britain’s literary heritage). We can see that fantasy has a very rich and deep heritage, even within the confines of a single culture.

Non-British historic fantasy works include things like Journey to the West (China) and the Divine Comedy (Italy)—and those are merely the ones I’m familiar with. There are thousands I don’t know about.

We can go even further back, to before Anglo-Saxon culture, to the Roman poem The Aeneid by Virgil (C20BC), which is basically Iliad(C1200BC) fanfic, and Homer’s works themselves clearly lie within the fantasy genre as clearly outlined in this article, although they predate the ‘modern’ concept of a novel (the first ‘novel’, as we understand it in modern terms, is the Japanese Tale of Genji (C1000AD), but that’s a political thriller/romance, not a fantasy story, and it’s classification is hotly debated).

Hell, one of the earliest stories we have, the Epic of Gilgamesh(C2100BC), is a fantasy story with gods and monsters.

Fantasy stories are as much a part of humanity and human literature as any other form of story—perhaps even more so—having been present in all levels of human society for thousands of years.

I would say the hobbit is more a retelling of the story of Sigurd more then anything else. The story elements very closely match with it, though it is possible the journey to the mountain itself has more elements of Beowulf.

Well, it’s likely that a blend of ideas were used. I’m not familiar with Sigurd, but I do have a passable knowledge of Beowulf, and it and the hobbit do share some parallels—particularly the dragon parts. The Dragon in Beowulf begins a rampage across the land after a thief steals a cup, and is slain when a vulnerable patch sacking scales on its belly is pieced—very similar to events towards the end of the Hobbit.

The oldest surviving piece of literature, the Epic of Gilgamesh, is quite fantastical.

But is it fantasy if the author thought they were real?

Yes. Belief does not shape reality.

Also, Gilgamesh was real.

It’s not fantasy, it’s mythology.

Fantasy all stems from mythology/tales/folklore that were told person to person before they were even ever written down.

Well I would argue that Fantasy was born in the 50s or maybe the 30s and is, therefore, at most 88 years old. But, I can equally well see why you would argue that it’s actually the oldest genre in the world. The problem with trying to claim things like The Odyssey as belonging to a particular contemporary genre is that it’s so influential in all fields of fiction, and the genre has changed a lot in that time, that it simply doesn’t feel authentically like it belongs in any genre.

That’s the problem with the literary canon, once you’re in there, you don’t belong anywhere else. I think of all works with fantasy elements published before the 1930s (i.e before The Hobbit and Conan) as “Protofantasy.” This includes The Odyessy, Gilgamesh, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and fairy tales. That’s just how I see it.

Very good explanation!

So when did we do the switch to MODERN fantasy?

Stories containing fantastic elements go all the way back.

However, the modern genre doesn’t go back nearly that far. There’s not really a clean break, but I think you can place the start of the modern fantasy genre near the turn of the century (a bit further back or a bit forward depending on where you want to draw the line between modern fantasy and its direct precursors.)

Modern fantasy tends to look back to old mythologies and rework elements found there, so in that sense the genre is as old as storytelling, and most certainly older than written language. However, I’m not sure we read these mythological elements in the same way today; in Shakespeare’s time there were people who honestly believed in fairies, whereas most readers of fantastic fiction now do not believe in real world counterparts to the elements borrowed from myths. When that shift occurred I don’t know. But to my knowledge, there was not a time when fantasy elements like magic fell out of use entirely.

I would argue that what we think of as fantasy now only dates back to Lord of the Rings, in the middle of the last century. What LotR did that nobody had really done before was to make the fantastical ordinary. It’s just a regular world, with regular people in it, some of whom happen to be hobbits, or whatever. There’s also magic.

Prior to that, and going back as long as time, are the myths, legends, folklore, fairy tales and superstitions, that have a lot of the same elements but treat them differently.

Even the sword and sorcery pulps, I think, have weird legendary people in them rather than the regular folk of Tolkien, and aren’t really like modern fantasy.

What is a genre in the first place? Are genres real? Are they eternal or temporary?

Great coverage. I was actually recommended to read War for the Oaks by a friend and she told me that this laid the foundation for the urban fantasy genre that is so popular today. And let me tell you guys, this book? It’s still relevant today.

It holds up better than many current books in the urban fantasy genre.

One thing to note is that the Epic of Gilgamesh is the oldest known piece of literature in recent memory. Good job!

Very well connected. Your analysis of fantasy’s presence through what is quite honestly the majority of Western literary history makes me wonder to what extent all fiction is fantasy to some extent – or to what varying degrees fantasy presents itself in works of fiction that are not distinctly labeled as capital-F “Fantasy” works. There are certainly widespread notes of heroism, supernatural events (even simply the deus ex machina convention), idealism, etc. that weave themselves through a great deal of the literature that resonates most enduringly with readers, and by your examination, I would bet that it has something to do with this millenia-spanning fascination with fantastic narratives.

Fantastic article! I think your observation that “the heroes of contemporary fantasy are defined by their relationship with the supernatural; they are heroes because of the supernatural presence in their lives, not always because of some unique inner quality” is particularly interesting. Seeing the ways contemporary authors and readers interpret and respond to different qualities in heroes (and the different definitions of what makes a ‘good’ story hero) is always fascinating.

Great article!

This is a wonderful article presenting the confluences of mythologies underscoring fantasy literatures and their stories. Great reference for modern fantasy!

Thought-provoking article, Sarai!

I am reminded of Game of Thrones, and how extensively G. R. R. Martin draws on the fantasy of his predecessors like Tolkien but with a post-modern twist.

For example, while Tolkien includes in his narrative an afterlife that looks to be inspired by his Christian beliefs (as you may know, Tolkien was a staunch Christian), Martin has John Snow profess that he sees no afterlife after being resurrected.

I interpreted Snow’s admissions of seeing no afterlife as Martin’s post-modern break from Tolkien’s tradition of depicting a Christian paradise (albeit with Scandinavian overtones).

Once again, great stuff!

I like how you have contextualised fantasy in its historicity and made a strong point that it is not only literature meant for children, but a cultural contribution to literature as whole

I think it might be misleading to think Fantasy-as a literary genre-existed in ancient times. It’s actually something very modern, a label, invented to revive the sense of wonder and fantastical in a one-dimensional modern world. Rather than seeing classical myth as ancient Fantasy, I’d say modern fantasy authors want to create myth of their own.