Film Marketing: A Lesson in Deception

Upon leaving the theater during a showing of Lucy the other night, disheartened movements and angry whispers filled the exit halls as large portions of the audience expressed their displeasure with the film. I noticed a considerable amount thoughts, ranging from “well that was strange,” to “I thought we were going to see an action movie.” This collective anger equated to countless negative responses to the film, most of them based solely on the marketing making the film seem like something it was not. This is not a trend that starts and ends with Lucy; in general, many movie-goers dismiss films because their expectations were not fully met. As a result, this can limit a film’s long term box office potential not because of any artistic faults it may have, but rather because of a ludicrous sense of self-entitlement that argues a film should wholly resemble the marketing campaign. The dislike of Lucy and other similarly marketed films shows that the difference between a film ‘s perception and its reality is merely a product of business and is unfair when used on its own to judge a film’s quality.

A marketing campaign’s goal is simply to draw as many moviegoers in as possible, particularly during opening weekend. It’s designed to take the most appealing parts of a film (however many there may or may not be) and translate them into a tease that entices audiences to buy tickets. As a result, this means that manipulation of the material is likely going to happen to best market it to general audiences. With Lucy, for example, all the trailers, posters, and T.V. spots leading up to its release touted Scarlett Johansson as a gun-wielding, ass-kicking machine. Lucy follows the story of the titular character as she’s tricked into being a drug mule by a Korean gangster. However, after accidentally digesting the drug, Lucy gains the ability to access over 20% of her brain’s capacity. With her capabilities only growing, it is up to Lucy to confront her captors as well as try to understand her growing knowledge of humanity itself. With that type of story, the marketing played up the idea of an action thriller, when there is actually minimal action throughout the picture; instead, the film focuses on large, scientific ideas/theories and thoughts about the state/future of humankind. The former is much easier to advertise (and significantly more appealing) to casual audiences than the latter.

The fact that Lucy won the weekend box office and made up its production budget within three days of release suggests that the marketing was an absolute triumph. The problem with this slight manipulation, however, is that a large chunk of the movie-going public (as well as people in general), have a sense of entitlement to nothing but the truth when it comes to a particular product. This predisposition, as a result, leads to an unfair criticism at what was purchased. Film audiences, for example, dismiss a movie than actually judge it because of a sense of betrayal. Some fail to understand that they are the ones that decided to buy a ticket in the first place and that the marketing simply succeeded at its job. It’s one thing to actually dislike the film because of how it is made, or how it executed its ideas, but it is absurd to not recommend it to others because you felt cheated by the marketing. An exceptionally useful tool in analyzing this trend and further highlighting the disconnect between certain films and audiences is the polling system, CinemaScore.

CinemaScore has been around since 1978, surveying movie-goers on opening nights to gauge reactions on the newest releases. Typically, this serves to judge word-of-mouth and predict long-term box office potential. Overall, the system does a very good job of gauging the reaction to a film, but it is not a great representation of the actual quality of the movie. Instead, there is a strong correlation between a film’s CinemaScore, its perception leading up to release, and overall box office potential. Transformers: Age of Extinction, for example, is a disaster with critics, yet holds an A- CinemaScore and a box office total that is well on its way to over $1 billion worldwide. Despite the fact that most consider it a bad film, the final product was an exact replication of the marketing: a mindless and aggressive action movie, thus resulting in a high CinemaScore and subsequent money-making success

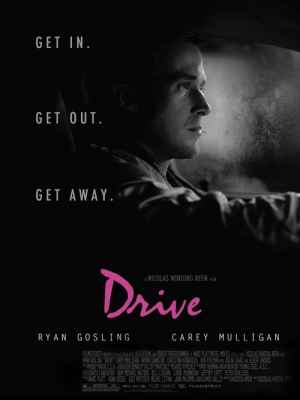

On the other hand, there are multiple other examples of films that gained a rough reaction from audiences based on the difference between its marketing and final product. Drive (2011) is a prime example of this trend. The story follows of a nameless Hollywood stunt driver (Ryan Gosling) who doubles as a freelance getaway driver. Though, once he gets involved with his neighbor Irene (Carey Mulligan), his life takes a turn for the unexpected, and upon Irene’s husband’s release from prison, he gets much more than he bargained for. With a plot structure like that, it is easy for the marketing campaign to play up more than what is really there. The marketing, therefore, sold the idea that the film would include several high-speed chases as well as violent action throughout. However, the film was in fact more of a character study about the nameless protagonist (with the occasional action scene) than a long, brutal thriller. After receiving a C- CinemaScore from audiences, the anger towards the marketing even prompted a Michigan woman to sue the distributor of the film on the grounds that the trailer was “misleading.” In 2010, The American was played up as a classic spy thriller led by George Clooney, but upon its release it was slammed by audiences, thus receiving a D- CinemaScore and suffering heavily at the box office. Despite both of these films receiving solid reviews by critics, general audiences turned them down because of the disparity between the advertising and the final, on-screen product.

In addition to both Drive and The American, another example of this trend is 2012’s Killing Them Softly, starring Brad Pitt. The film received an F CinemaScore and bombed financially because audiences were not expecting the startling political commentary that was prevalent throughout the film, but completely absent in the marketing. It didn’t matter that the film had a very good score of 75% on Rotten Tomatoes. Instead, audiences were displeased because of a misplaced sense of betrayal and anger, leading others to disprove of the film as well, before even seeing it for themselves. Like Drive and The American, Killing Them Softly suffered financially because audiences were more upset with the marketing than any real fault that the film may have had.

Some would argue, however, that anger towards a film that is vastly different from its marketing is fully justifiable. They would say that it is unfair for the consumer to be surprised by such a vast change because that was not expected by them. The problem with that claim, though, is that a person can research the film they are about to go see and make sure that it is (or isn’t) what they expect. The element of surprise is removable, if a person so chooses. The responsibility, therefore, falls on them if the film is different from how its advertisements. Lucy may have won the weekend box office, but time will tell if it will suffer from its poor word-of-mouth like other similarly marketed films.

Ultimately, complete truth towards an audience is not necessary from a marketing campaign. Its job is to sell a product as best it can. Therefore, the disconnect between the film’s marketing and the final onscreen product should not be the sole factor in determining whether a picture is “good” or “bad.” When someone buys a ticket for a film based on how it looks, that is simply the marketing succeeding in its job. The sense of entitlement that is prevalent throughout the public is misdirected. Moviegoers need to understand that studios do not owe them anything. If audiences really want to avoid being tricked, it is up to them to do the research and not blame the marketing. It is more than okay to dislike a film because of any problems that it may or may not have, but there is no need to discount it because of how its advertising chose to sell it.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

This is really fascinating to me. I’ve been on the experiencing end of this a few times that stand out in recent past, most notably the film Tammy. Every commercial I saw made it seem like a crime comedy kind of thing, and in reality the film was really heartwarming and quite wonderful and much more than that one scene that was in all the trailers. Marketing is something interesting… It’s definitely one thing to get people into the seats, but if you can’t keep them there with truth, then what kind of thing are you really creating? I’m just sort of rambling at this point, sorry. In any case, excellent and super thought provoking article!

Great thoughts. I agree that the marketing is indeed only there to get moviegoers to go see the movie, but I also agree that audiences have every right to hold their sense of entitlement to seeing a movie as represented by trailers. Being deceived by a clever marketing ploy leaves people feeling jipped, especially considering how expensive movies are now. People show up feeling like seeing a particular types of film, so if they are shown something different than expected, maybe they are not just unfairly giving up on the film, they are actually rightfully angry.

Lucy wasn’t what I expected at all. I did not care to much for the film. The trailer is misleading and it shows the best parts. It isn’t worth paying full price to see it. It had to do with humans being compared to Animals and what percentage of the brain we use. It was like watching limitless. I had to sit there and listen to morgan freemans lectures in order to keep up with what was going on with the movie.

Just for the record, humans ARE animals.

The premise does sound a lot like Limitless.

With an estimated 1000 trillion neurotransmitter connections in the average adult brain, any movie that would deal with this highly dormant grey matter, particularly in our politicians, might just stimulate a rush to find out what potential actually means in the realm of low-down-knee-walking-curb-caressing-followers-of-followers mentality. And I never met Lucy in the sky to arrive at this two brain-cell conclusion.

Holly-weird has made its bed, and is already sleeping in it. The overseas market in China has now over taken the USA in ticket sales. Even AMC, one of the largest theater chains in the world, is owned by a Billionaire from China. I was fired as a union projectionist when all the crazy digital stuff was rammed up every ones A$$. It all happened in one night. Thursday I was there, Friday I was Fired. And the movie theaters have been going right down the toilet since. They have to pay millions of $ dollars for the new brighter picture that comes from the heavens above! I have been to a movie only once in the last 3 years. Never again. I will stay away.

Hollywood is out of ideas, most movies are remakes or 2 hours of special effects. Movies are very overpriced so I will wait for it to come to Netflix. With the cost of living going up then guess what suffers… The movie industry. There are no actors/actresses that can get me to a movie anymore. Tom Hanks has the best chance but to many weirdos are in Hollywood. I can’t stand 90% of these phonies with their fake causes and agendas. Someone else can pay their salaries becuase I won’t!

I agree regarding Hollywood’s lack of originality, they were quite fond of remaking anything.

“I love Lucy” I read the reviews before the film and did see the trailers and the movie really met my expectations. One movie I remember that disappointed me in the past was Vanilla Sky with Tom Cruise I thought that was going to be action back but it was more psychological drama.

Great piece. You are so right of course. I’ve been misled by trailers many, many times but I do not get mad for the reasons you stated. Marketing is marketing and honestly, in their position, I might do the same thing. But I love how you spun this and the examples you’ve provided. Now I gotta watch those movies and really see what they’re all about.

So many reasons for lackluster ticket sales: (1) high unemployment of typical moviegoer (2) outstanding debt (such as student loans) (3) higher ticket prices (escalating faster than inflationary rate) (4) cheaper alternatives (renting or payTV) (5) safer to stay away (violence or unsanitary/unhealthy theatre complex) (6) Large screen and excessive volume does not add to movie enjoyment . . . but distracts/annoys (7) Movie stars are over-rated and over-paid . . . adding to excessive ticket prices (8) lack of original, quality movies (9) many alternative options (video games, internet, YouTube, Hulu, Netflix, World’s Dumbest selfies). In short: What is left of Hollywood’s business model is in trouble. HUGE TROUBLE.

And even if one could overcome all those negatives there is 10) The Audience. Texting, emailing, talking, eating, eating, eating, eating, eating and talking. No thank you, those flashes of light are so distracting. Oh, sorry, gotta text.

The golden era of Hollywood is long gone. I went to see Neighbors with my 17 year old. We both agreed to leave halfway through. Walking away the worst movie I have ever seen. I will never go back to a theater again.

So Lucy only got an audience C+ and only middling Rotten Tomatoes and got $44 mill? Something isn’t right. Please don’t let this mean more movies starring Johansson. It’s an aberration, just like Jolie’s recent movie success was an aberration, but we’ll probably get barraged with movies starring both now.

With the cost of living out-pacing salaries, I’m sick of the Hollywood elites who don’t have a clue that their fan-base is struggling when they complain they don’t have enough. Lastly, I’m sick of the political agendas being foisted into every plot.

I saw Lucy last night. What a load of sexy mindless drivel. I didn’t expect anything more, like when I tune in to an occasional ep of American Idol (for E. G.), and happily parted with my fifteen bucks for the ticket (and same again for popcorn etc). I was troubled though by some of the mindless violence (hospital scenes especially, given recent real events). Well done Samsung… I wonder how much they parted with. Surprised Soda Stream wasn’t featured… It was what it was. The biggest, most positive, reaction from my fellow audience members came in reaction to the 50 Shades trailer – they applauded! wtf. Has the world gone mad.

–Tike

It seems like I might as well just rewatch the fifth element than watch lucy

I wholly disagreed with you until that second to last paragraph, in which you partially won me over. I agree that consumers need to be more conscious of what they’re consuming. People too often trust advertisements or rumors when spending money, rather than doing their own research. This can be seen in the video game industry, where pre-orders are a big thing. People put down money on a game to which their only exposure (until the time of release) is content from the creators who want to sell them the game. Of course the screenshots and trailers are going to look good; they want to lock in your money a.s.a.p.! It’s far more prudent to wait until a game’s (or any other item’s) release, when people can review it.

However, I don’t think it’s correct to completely defend movie marketing campaigns. It’s true that Lucy and the other films you mentioned are probably better than they’re being received. I even want to see Lucy more now that I’ve heard it’s not an action thriller. That doesn’t excuse the marketers for being pretty scummy. Consumers need to be more responsible, but so do advertisers. Selling a movie as an action thriller when it’s really a more psychological film is tantamount to false advertisement. If someone sold me a Mac computer under the impression that it was a Windows computer, I’d be pretty upset. Both sides are accountible in these types of scenarios.

If I am understanding this article correctly, it appears to be suggesting that film goers are responsible for being susceptible to false advertising, and that they should not have the expectation that they should not be lied to by big business. That viewers should research a movie like they research a car before they purchase a ticket to a film (spoiling the movie in the process).

I find it morally bankrupt to suggest that consumers do not have a right to be upset when they are victims of false advertising. How is the general public supposed to sort out the commercials that are lying from the from the ones that are more accurately representing their product? Why would they want to spoil the movie for themselves? Why would anyone suggest to them that they should spoil the movie?

If we applied this logic to another product like Lucky Charms cereal, it would seem that it would be appropriate to blame the consumer when the poor the cereal out and find Cheerios instead. I understand you suggest a consumer has access to the internet, and could research (and spoil) the movie for themselves in order to identify if the movie commercial accurately represented its film. I’m not sure why this is a reasonable suggestion. Most movie goers confront a film like they do their cereal and draw the likely inference that the box is representative of its contents.

Interrogating Ideology With A Chainsaw

http://interrogatingideologywithachainsaw.blogspot.com/

Not that the studios have ever been in the business for artistic integrity, but this is another way in which the formalizing of their economic models are going to continue eroding the quality of what they release. Katzenburg from Dreamworks said a few months ago that he predicted all major releases would have three week theatrical runs within the next few years, because that is when most films make the lions share of their money anyway. Under that model, it seems that the quality of the film will be unimportant next to the effectiveness of the marketing campaign.

Another (possibly) prescient idea came from the New Yorker’s Richard Brody last week. He proposed that the investment of wealthy producers in auteur films over the last few years (think Megan Ellison funding PTA’s ‘The Master’) was more akin to a patron donating money to the Metropolitan Opera than someone making an investment for financial reasons. The film was funded because the investor wanted the film as opposed to the return on investment. I’m sure she wanted both, but you understand.

This is to say that the films that the industry knows how to make money on are the ones that they produce solely to that end, and the other movies (I think your three examples fit fairly well into this mold) that aren’t made as products, but as attempts at art are still obliged to be fed through the same system as the others. People aren’t going to stop making films as art, but the way things are going, I feel like the current system is only going to squeeze out more and more movies like ‘Drive’. The more movie theaters become like amusement park rides, the more we’ll have to rely on alternate distribution methods to see interesting films.

To me, the marketing for last year’s 47 Ronin was even more dishonest than the practices utilized in promoting Lucy. It is sad to me that producers think so little of the American movie-going public; they believed a classic tale of Japanese–and world–mythology would not read well with Western audiences without. Hence the inclusion of a damsel in distress subplot, along with the marketing that erroneously highlights Keanu Reeves as the film’s lead character.

The relationship between the trailers for a movie, the marketing aspect, and the content of the film itself is interesting. As you noted, many film goers become angry, or feel deceived, if the movie they see does not conform to their expectations as created by the marketing for that movie. I have seen this as well, and am completely stumped as to why this should be the case.

My stumpedness comes from a general perception about all advertising, not just the advertising done for movies. I am stumped simply, or simply stumped, because I do not understand why anybody would believe in an advertisement or advertising campaign in the first place. As you put it at the end of your article, marketing is designed to sell a product. This is sole and only purpose of advertising. I cannot figure out why people believe that what they see or hear in ads or in marketing campaigns in any way resembles the truth. When I discuss this with friends, their answer is straightforward: people are stupid and will believe most anything you tell them. I am trying not to fall into this explanation, but the more ads I see, and the more times people purchase products, or services, or entertainment on the basis of ads, I despair.

Why would anyone believe that a trailer for “Lucy” – a couple of minutes of spliced together moments from an 89 minute movie – actually resemble what takes place in the movie entire? Why do people think that they can lose weight by not exercising, by not changing their diet, but by taking a pill? Why do people believe that the guy in the white coat in the commercial is an actual doctor dispensing actually true medical advice. Even if he is in fact a doctor, though this is the exception, he is certainly being paid to be in the ad. Why would anybody trust someone who is being paid to push a position?

Your article hits a note that has been a source of never-ending frustration for me, in that I cannot figure out why advertising works. You noted that people were angry or felt cheated because “Lucy” did not resemble the advertising they had seen about the movie. Did anyone ever ask them why they thought it should?

Giovanni,

Love the insight of this article. Awesome analysis. I totally agree that audiences need to understand that they aren’t owed anything. A film is certainly made for an audience, but to feel betrayed by a disconnect between advertising and product is the nature of American life! If everyone got worked up about false advertising every business from Macdonalds to Victoria’s Secret would be going under.

Advertising is a funny thing to me. I have a love/ hate relationship with it. I hate the psychological manipulation that it employs but I love the process of breaking that manipulation down. I’ve been told I pay too much attention to commercials but I only do that because I like to be an active viewer. I’m never swayed by an advertising campaign but I can appreciate the creative and psychological process the writers of the campaign use. The author Don Delillo discusses this concept in his novel “White Noise”. He calls it “psychic energy”. Basically it’s the notion that almost everything in our modern age is a means of swaying a customer to believe something about a product. It seems like a dangerous combination when professional film makers are in control of a stylized advertisement, which is basically a short film in itself.

I like this piece a lot because I see this as a growing trend in cinema. Marketing movies as discussed here may be successful in getting the monetary goals reached, but is it truly what should be done or is it in some sense unethical? “The Grey” was another one that I know was panned by people who went to go see Nesson kick wolf A** but instead received a very intimate and up close man vs nature story. I think if anything this trend will make people start to actually give more care into movies they see and maybe do research before hand. Too often people go to just be blindly shown images on a screen that they do not give much thought to the story being told. This misleading trend in trailers and marketing may inspire a more thoughtful generation of movie goers.

The “deception” described here is basically one of the multiple capitalism’s strategies of enticement.