Anonymous Graffiti in China: a New Form of Demotivational Culture?

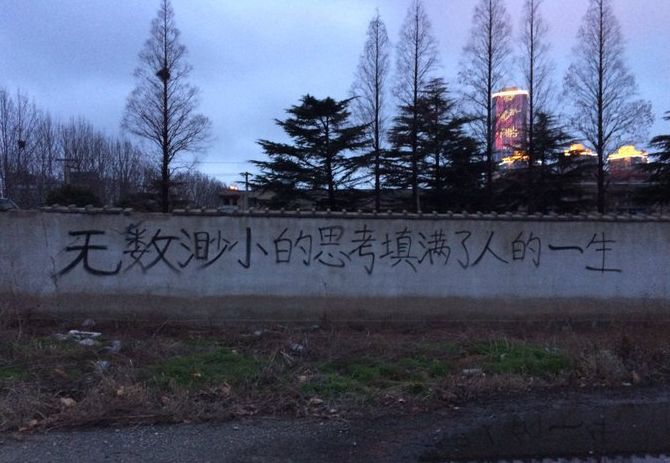

Posted on Weibo, a Chinese microblogging application, a photo of an anonymous graffiti has been shared and reused by many people at the beginning of 2020 on the Chinese internet. What can be seen in this photo is a wasted wall standing on the land, with the background of trees in winter and high-rise buildings which are decorated with neon light – a contrast between the ruined, unnoticeable area and the well-designed part in the same city. The graffiti on the wall is a poetic slogan written in Chinese: Uncountable tiny thoughts fill the whole life of a man (无数渺小的思考填满了人的一生). This sentence is cited from Ludwig Wittgenstein, an Austrian-British philosopher, in his Culture and Value on page 57. The original sentence is “How small a thought it takes to fill a whole life”. 1

Spread as a meme among the Chinese social media, the picture is used to show the loneliness and emptiness felt by netizens. Slogans painted on the wall, which are germane to the government’s pedagogical purpose, can often be seen in Chinese cities. The contents of the slogans are usually positive words to encourage citizens or educational sentences on environmental protection and civilization. On the contrary, the graffiti with Wittgenstein’s words is also in a slogan form but without the common positive or pedagogical meanings. While the author of the graffiti remains anonymous, I happened to find him and have a short chat with. “I saw this saying of Wittgenstein from one of my friends on twitter, and it stays in my mind. That day I wanted to draw something with my paint spray but with no prepared scripts, and then this sentence popped up.” Said the author, a high school student who is about to attend the college entrance examination. He has a crush on a girl just like many other Chinese teenagers at this age. He told me that “what I want to express from the graffiti is I really love that girl, but no one knows and understands. That is the only thing I would like you to know. People may have similar sadness feelings when they see and spread it on social media, but the original meaning has dissolved like an iceberg.”

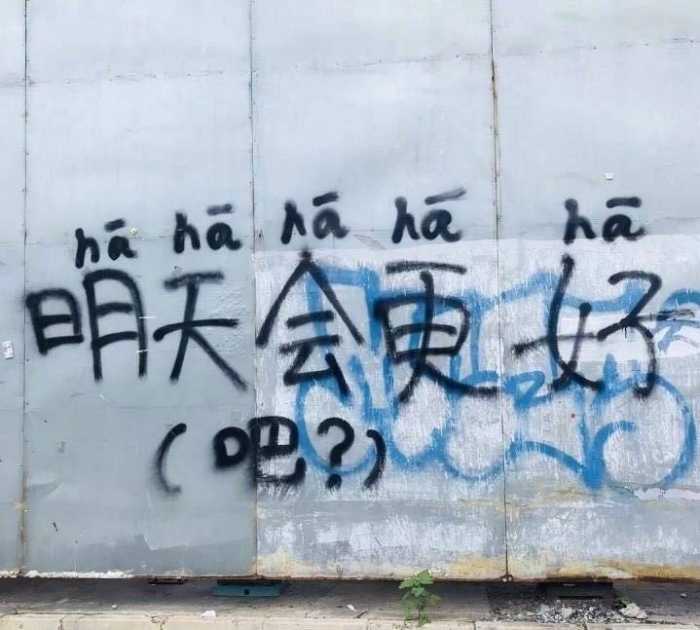

Likewise, another photo, which is disseminated during the COVID-19 pandemic, is a slogan “have no right to pessimism (没有悲观的权利)” on a wall which seems to be the ruins of a house in the rural area. The slogan is quoted from Nietzsche, “a sufferer has no right to pessimism because he suffers”. Despite Nietzsche’s original meaning, this photo is used on Chinese social media as memes to indicate the desolation and the disappointment to the online censorship which prevents the questioning of the government’s policies. Some other photos on anonymous graffiti are also about depression feelings, including words such as disappointment, lack of happiness, and regrets. There are also reactions to the optimistic or the so-called “positive energy” discourse which is often used in the government’s official slogans. For instance, one of the graffiti paints “tomorrow will be better” and leaves a question mark underneath.

Demotivational subculture

Demotivational subculture in China is represented by the prevalence of a meme named “Ge You Slouch” in 2016 and 2017. The meme is a screenshot from a Chinese sitcom called I Love My Family (我爱我家) directed by Ying Da, screened in 1994. In the screenshot, a middle-aged homeless man, acted by the Chinese actor Ge You, lies lazily on a couch. From his facial expression and posture, it can be understood that he is thoroughly demotivated. The meme has been soon popular among the Chinese young generation online, used together with words such as “I am a loser” and “life is just good to be unproductive”. Negative dialogues in BoJack Horseman such as “life is just long, hard kick in the urethra” have been used as memes by the Chinese netizens. The quote from Japanese writer Osamu Dazai, who ends his life by suicide, “sorry for being a human” (生まれて、すみません) frequently appears. This subculture China can also be seen early in East Asian countries like Japan, manifested by Atsushi Miura’s book Downwardly Mobile Society (2005) which explores the Japanese middle class and their lack of passion for communicating, working, studying, and consuming.

Businesses driven by the demotivational subculture have also been developed in China. For instance, in contrast to a Chinese bubble tea chain store named “happy tea” (喜茶), another bubble tea labelled by “sang”(丧) or dispirited has appeared and been accepted by a large number of the young people. Reuters has a news report on this phenomenon – “Chinese millennials with a dim view of their career and marriage prospects can wallow in despair with a range of teas such as ‘achieved-absolutely-nothing black tea’, and ‘my-ex’s-life-is-better-than-mine fruit tea’”. 2 In this report, the author Chen and Munroe believe that the prevalence of demotivational culture is due to the encounter of the youth’s high life expectancy and the facts of low salary and high competitiveness in the job market in the Chinese society, which post a burden on the life of the young generation. 3

Actually, there are many other reasons for the demotivation among Chinese youth apart from what has been given by the news report. For example, the unaffordable house price in the major cities unavoidably leads to decades of loans. Growing social stratification makes life harder to be changed by hardworking and good grades. Child-rearing in a competitive society, which requires the parents to devote their savings and nearly all of their spare time to children, is also a source of anxiety and desperation. Additionally, the inefficiency of laws and regulations in protecting vulnerable groups such as women and people with a mental or physical disability leads to disappointment. In this environment, the young generation, most of which are students and middle class, cannot stay positive continuously as what is advocated by the government, and the demotivational culture, therefore, emerged as an expression of this powerlessness.

This subculture, however, is discouraged by the Chinese government because of its opposition from the official ideology. In its comment in August 2017, People’s Daily, a government’s official newspaper institute, labelled the demotivational subculture as “spiritual opium”, claimed that this culture is an invasion from the outside such as Japan and English literature A Catcher in the Rye, and called for not drinking sang tea (now has been renamed song tea in China). 4 This might be one of the reasons why song tea is not as popular as its condition in 2017-2018. However, while the newspaper recognizes there are pressures in life brought by house price, employment, college entrance, and marriage, it merely encourages the youth to “face the problem and keep fighting” and does not understand the essential reason of the youth’s desolation can be traced back to the problems in law and regulations and the government’s inefficiency in addressing these issues. Thus, although the bubble tea may disappear, the desolation sentiment still exists and the youth need a way for expression.

Graffiti in the Chinese context

While the government’s propaganda pictures and slogans can be also deemed as graffiti, there are technically two types of non-official graffiti in China. One is the graffiti for the decorative purpose as a part of “city beautification”, seen in Beijing 798 Art Zone and Shanghai Moganshan Road. Done by professional artists for money-making, these graffiti do not contain offensive words or images towards any institutes or social groups to avoid being eliminated. 5 On the contrary, the other form of graffiti is made grassroots, which is opposite to the purpose of the former one. This includes the graffiti left by tourists on the wall of attractions, the graffiti in the corner of the university and high school campuses, and the anonymous graffiti on the streets. These grassroots graffiti in most times look random and do not have explicit meanings.

However, according to Nick Smith, there is also a number of grassroots graffiti in China that show clear resistance. Smith noticed the slogans “protecting ancient towns is everyone’s responsibility” (baohu guzhen renren youze 保护古镇人人有责)” written by the residents on the buildings in a historical district which is about to be demolished by the local government in Chongqing, China. 6 Smith, in this article, calls this contestation as “spatial poetics”, which is an alternative expression under the authoritarian contexts. 7 While the demands from the residents against the redevelopment of this district are ignored by the local government, the protestors seek another way – namely, graffiti on the walls – to visualize their disappointment.

A comparison can be made here between the “spacial poetics” in Smith’s work and the graffiti in this article. The content of the memes are constant to the demotivational subculture and bear similarities with the slogans in Smith’s work, conveying feelings of dissatisfaction and desolation towards what has been imposed on the young generation. However, while the graffiti in Chongqing is more explicit and related to a protesting campaign, the memes in this article seems to be more implicit. First, according to the current pictures online, most of the graffiti are in the wasted areas unnoticeable to the mass public. The reason behind it is that if they are painted overtly, they will face a risk of being eradicated for violating city beautification regulations. The government’s discouragement on demotivational subculture years ago can be another reason. In addition, most of the graffiti and memes just suggest a very vague feeling of sorrow.

In this way, can the graffiti photos used as memes on Chinese social media be regarded as another form of resistance? While they do suggest opposition to the official mainstream culture, what should be noted here is that these graffiti and memes are not powerful enough to evoke another demotivational wave on Chinese social media nor draw the attention of the government. Viewing individually, each meme even seems not distinguished among the numerous memes online. People who made the graffiti and people who repost them may also not aim at resistance. They recognize the pressure and hardness in their life, realize that it is extremely hard to make a change, and have to let this off through an anonymous, implicit, and powerless way.

Works Cited

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Culture and value. University of Chicago Press, 1984. ↩

- Chen, Yawen, and Munroe, Tony. 2017. “For Chinese millennials, despondency has a brand name.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-congress-millennials-insight/for-chinese-millennials-despondency-has-a-brand-name-idUSKCN1BF2J7 (accessed 27 May, 2020). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Feng, Jiayun. 2017. “People’s Daily: Stay away from the opium of demotivational culture.” SupChina. https://supchina.com/2017/08/18/peoples-daily-stay-away-opium-demotivational-culture-chinas-latest-society-culture-news/ (accessed 27 May, 2020). ↩

- Bruno, Debra. 2012. “The lonely life of the Chinese graffiti writer.” Citylab. https://www.citylab.com/design/2012/05/lonely-life-chinese-graffiti-writer/2099/ (accessed 29 May, 2020). ↩

- Smith, Nick R. 2020. “Spatial Poetics Under Authoritarianism: Graffiti and the Contestation of Urban Redevelopment in Contemporary China.” Antipode 52, no. 2 (2020): 581-601. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Lovely stuff. Have you watched “Spray Paint Beijing” (2016)? It is a great resource for learning more about this artistic movement that is on the verge of exploding.

Thank you for the recommendation! I have watched the trailer of that documentary several months ago but not the full film – really appreciate the work of these Chinese artists.

I found this article utterly fascinating! I definitely learned something new today. Great work! 🙂

Nice to see the beginning of a graffiti scene in china.

I’ve always loved graffiti Art, so long as it’s not a nuisance. Some guy in Hong Kong made a name for himself graffiting everywhere. He claimed his family had an claim to all of Kowloon and thus named himself the “Kimg of Kowloon” in his graffiti. Some of it has been preserved as a national monument.

Haha that’s interesting. There are also graffiti making nonsense in Mainland China but more endorsement should be given to the artists

I heard about ink on Great Wall.

I’ve always found graffiti on ancient monuments despicable. Graffiti on modern buildings, when it’s protest graffiti, is understandable, but on ancient monuments? What kind of person thinks that they have the right to do that?

I would agree normally except this wall is so huge it shouldn’t even matter.

Seeing as a lot of the bits tourists get to see are only slightly more ancient than I am I don’t really see a problem.

It’s not like doodling on the Mona Lisa.

Great topic. Graffiti has been a vigorously spreading phenomenon and very often under appreciated.

Great timing, as young people everywhere are feeling anxious about what the future holds with this pandemic.

Yes I think the pandemic has made some existed negative sentiments towards power, social structure, etc uncovered (or amplified). It also adds to new anxiety, and social media help circulate them

An good essay. The reference to different types of bubble tea is interesting.

I lived in China for many years, and used to be into graffiti. The majority of artists deliberately seem to avoid graffiti as a political action or statement. Although this is changing as of recently.

Agree. This is a sad condition. The most famous graffiti artist is Dali Zhang I guess and others are not known by the public…hope this will change in the future

One major difference in graffiti in the West and China is that graffiti is not regarded primarily as vandalism by the public and officials, at least as long as it appears in certain areas and without clear political content.

Oh that’s great…China still has a long way to go

I guess officials have adopted a limited tolerance towards graffiti to prevent it from becoming a serious political problem. 🙂

If they would start to tag and bomb everything, the situation would obviously change and the government would not be so tolerant.

Graffiti has become an inspiring field of dialogue between the public and the central Chinese government. Although compared to the west, it is yet to bloom.

I see graffiti as a form of defiance.

It’s interesting how graffiti has always been regarded as an illegal and destruc-tive subcultural art form.

What a fascinating read. The writing, as they say, is on the wall.

What an engaging and enlightening article! Thank you for this, XiaoYang. I never knew about this “demotivational subculture” in China. I also like how you explore the multiple possible implications of this graffiti. Whether an explicit rebellion or an implicit and benign expression of dissatisfaction, it’s another important aspect of the contention that exists between the Chinese people and its government.

Glad you like it 🙂

Awesome article, thank you. I recommend the book Graffiti Asia for further reading and visuals.

Thanks for the recommendation!

Graffiti in China is essentially protected by its very smallness.

China has a tradition of calligraphy so I can see this becoming huge there in the coming years.

Shanghai is quite the hotspot for famous street artists!

I wouldn’t dare to draw anything in China. Getting caught there… I could not even imagine it.

In China, graffiti has not led to censorship, but rather to an alternative form of communication is worthy of recognition.

I love graffiti and tagging. I see trains come through here (Cincinnati, Ohio) all the time with it.

If art has the ability of transforming and inspiring society, this is surely something we should support.

Wow! I love this article.