Historical New York Musicals and the Human Spirit

New York City is one of the most ubiquitous settings across mediums, from classic literature to modern movies and musicals. Novels like The Great Gatsby and A Tree Grows in Brooklyn have captivated readers for over a century, perhaps because in them, New York functions almost as a sentient setting. Contemporary authors such as Cecily Von Ziegesar of Gossip Girl and Cobble Hill fame, say New York is “just as much a character as the people” in their plots. Enchanting romantic comedies such as Autumn in New York, When Harry Met Sally, and You’ve Got Mail make “true love” seem possible, partly because of the gritty charm of their settings. Many warmhearted, “family” Christmas films, from Miracle on 34th Street to Home Alone 2 take place in New York City, as well. Scenes shot in iconic locations, such as in front of the Rockefeller Center tree, lend an extra bit of “fairy dust” to inherent holiday magic.

Perhaps no medium embraces New York City (NYC) quite like the musical, however, since most beloved musicals get their start on Broadway, this might seem an obvious conclusion. If anything, setting a musical in NYC might feel trite and tired. However, New York-set musicals bear a certain gravitas, even a certain magic, the average musical performed in New York doesn’t bear. In particular, New York-set musicals with a historical background contain this element. They, perhaps more than any other musicals, testify to the human spirit. They show viewers how that human spirit can grow through stages as the main characters come of age and NYC does so alongside them. These musicals also prove NYC retains its magic, its place as the hub of dreams and possibilities, long after the era of a given show has given way to contemporary times.

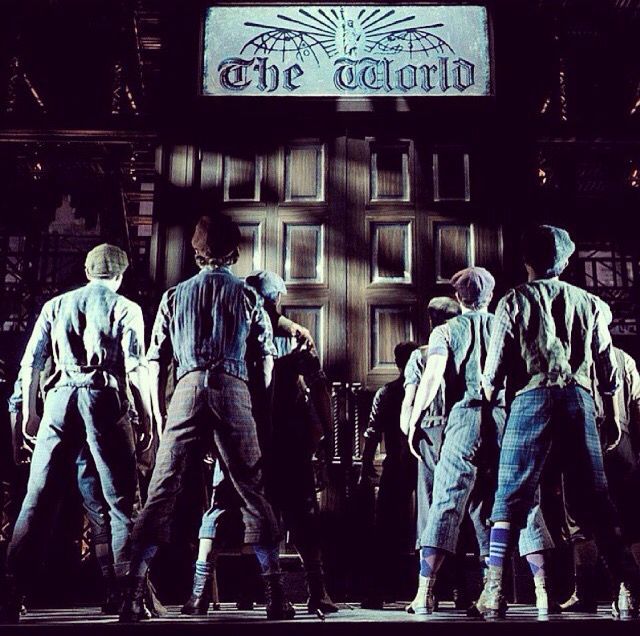

Three particular musicals form a trifecta that embraces the human spirit, and the tough yet hopeful spirit of NYC, more than any others. Annie, Newsies, and Hamilton pack plenty of grit, hope, reality, and dreams into their one-word titles. Their protagonists show us three distinct stages of coming of age, embracing one’s identity and one’s home. The musicals’ plots, through both story and song, show viewers what it takes for the best of humanity to endure in what can be one of America’s harshest environments. Thus, viewers of these NYC musicals leave the theater with a deeper love for New York and renewed hope that they, like their fictional counterparts, can make their marks no matter how “big, loud, and tough” their environments are (Annie, 1999, track 8).

Annie

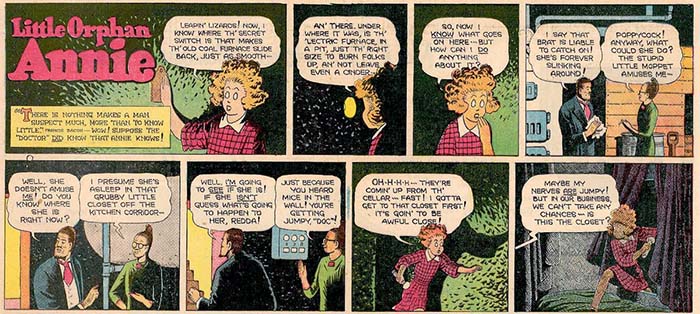

Based on the Harold Gray comic strip created in 1924, and the radio show that debuted seven years later in 1931, Annie is perhaps the first musical thought of in terms of historical New York City. In many ways, Annie is musical theater’s version of Cinderella, down to the character types, the rags to riches plot, and the guaranteed happy ending. It’s as beloved as Cinderella, too. Annie, or Little Orphan Annie as she was first known, has graced not only a comic strip, a radio show, and a Broadway musical, but had her story adapted to film three times. The first Annie film, which debuted in 1982, spawned the sequel Annie: A Royal Adventure in 1995. Royal Adventure was meant to be the second in a series of films starring the spunky redhead. The series never got off the ground, and some Annie aficionados don’t accept Royal Adventure as canon. However, Annie’s story, pluck, and optimism remain entrenched in audiences’ hearts. Once they find her, whether that’s onstage in the original musical or through film, most people can find something to appreciate and relate to in Annie.

Annie as a NYC Heroine

Annie’s story opens in New York City, 1933, the middle of America’s Great Depression. At the time, the country still reeled from the stock market crash of 1929. Unemployment soared, topping out at about 25%.This amounted to about 15 million unemployed Americans and a “redundant” workforce.

As grim as that reality was for adults, children suffered a much greater fallout. “Malnutrition, hunger, and displacement” were common, as were “emotional and psychological problems as a result of living in constant uncertainty and [children] seeing their families in hardship” (Kate 2020). Child labor became ubiquitous, as children dropped out of school to accompany their parents at work or more often, work independently at “manual labor [for] long, grueling hours.”

Many children did not have parents to accompany to work or help provide for, nor could they get even the most unskilled jobs. Those children were the Depression’s orphans, many of whom lived on the streets in places like New York, and many of whom were physically or mentally handicapped. Statistics estimate that “more than 200,000 vagrant children wandered the country as a result of the breakup of their families.” Even those children whose families did not fall apart had no guarantee of keeping their parents for long. The Depression’s infant and maternal mortality rates were extremely high, often owing to rampant disease, poor sanitation, and the neglect of medical and dental care for lack of funds.

The titular character of Annie is one of those orphans, one of those “vagrant children.” When we meet her, she is arguably better off than many contemporaries. She’s about ten years old, meaning she’s still young enough to have a chance at adoption. She’s living not on the streets, but in a NYC orphanage, Miss Hannigan’s (sometimes rendered as Miss Hannigan’s Home for Lost Girls or, in the 1982 film, Hudson Street Home for Girls). A placard on the 1982 film’s building tells us Miss Hannigan’s was established in 1856, meaning it’s been a fixture in Annie’s area of NYC for nearly 80 years. In other words, our protagonist should be fairly safe and secure for a child growing up in the Depression. She has a roof, and presumably a bed and regular meals. Her city has established a particular refuge, not only for orphan children but orphan girls in particular. This would ordinarily make Annie even safer than normal, considering the alternative of living on the streets would be physically and emotionally harder on a female. Additionally, Annie’s age and Miss Hannigan’s would presumably protect her from common fates of orphan girls at the time, such as kidnapping, prostitution, or unwanted pregnancy–the latter of which would continue feeding the orphan crisis.

Miss Hannigan’s, however, is far from the safe harbor it purports to be. The eponymous matron cares little or nothing for the girls in her charge. For Miss Hannigan, Annie and friends are nothing more than cleaning slaves. They wake up in the early hours of the morning–still the middle of the night–to begin harsh days of washing dishes, scrubbing floors, doing laundry, and presumably sewing dresses for customers whose pay Miss Hannigan will pocket (Marshall 1999). The girls are not fed regularly or at all; being “denied food as punishment” can be a daily occurrence (TV Tropes). Miss Hannigan doesn’t abuse anyone physically, but as Annie puts it in the 1999 version, closest to the musical, “You’ve threatened. That’s worse.” Miss Hannigan indulges in a smirk and low chuckle as she agrees, “I know” (Marshall 1999).

Annie’s story doesn’t give viewers a terribly harsh view of Depression-era NYC. If anything, it’s highly sanitized. That said, Miss Hannigan knows exactly where her little inmates would be without her, and enjoys holding it over their heads. She forces the girls to chant, “We love you, Miss Hannigan” in unison anytime she pleases. She also drills it into the girls never to tell a lie, implying that without her, they might do such things because they are wicked children or, as the 1982 version puts it, “little pig droppings” (Huston 1982). This implied gaslighting, plus Hannigan’s complete hypocrisy, makes her abuse arguably worse than if she engaged in harsher methods. By the time we meet Annie, she has lived under this treatment almost 11 years, and will risk escape and the streets of New York rather than continue suffering.

Annie’s era and bleak circumstances, made that much bleaker because appearances deny her reality, make her an ideal Depression-era heroine. She’s also an ideal representation of New York’s indomitable spirit. As we discover when she escapes Miss Hannigan’s, Annie is a courageous and plucky girl. She maintains optimism, singing about a sunny outlook for “Tomorrow” although, in the musical and at least one film, her escape leaves her cold and still starving. Annie does steal an ear of hot corn in one film, but viewers can clearly see she needs to and had no malice aforethought. The little she has, she almost immediately gives to the stray dog Sandy, who becomes her pet.

In other words, Annie refuses to let her “depressed” circumstances define her. She puts others first and maintains a generous heart. Her moral compass may be a bit tarnished thanks to her hardscrabble existence, but she’s in no way corrupted. Annie embodies the hardy, “chin up” attitude many people strove for during the Depression. Her focus on “tomorrow” not only helps her keep that attitude, but communicates she still has dreams for her future. Unlike most orphans, and many adults, she fully expects them to come true too, and perhaps sooner than she thinks. After all, if NYC can spare one ear of hot corn for a runaway orphan, or provide the bare minimum of a home for one, surely it has enough room for that orphan’s life to take a turn for the better.

Annie’s freedom doesn’t last long; the cops are already looking for a missing orphan girl her size, and she was so eager to get out of Hannigan’s clutches, she didn’t have time to plan for eventualities like food or decent shelter. Moreover, Annie’s a resilient kid, but probably doesn’t have the street smarts to compete with older, stronger orphans who would have better access to resources. However, Annie does meet Sandy before she’s returned to Hannigan’s. She intends to share her new pet with the other girls, making him a sort of mascot. The 1982 film gives us the extra song “Sandy,” showing the dog’s presence helps Annie maintain hope, although yet another of her many escapes has failed. Indeed, Sandy is an indication that Annie’s long-held hope for a better life may finally be rewarded.

Annie as Princess of a NYC Fairy Tale

That reward comes within moments of Annie’s return to Miss Hannigan. A soft-spoken, well-dressed woman named Grace Farrell shows up “to inquire about an orphan,” and the entire orphanage gains yet another spark of hope. Perhaps Miss Farrell is looking for a cleaning girl, which would give one lucky denizen a way out. Failing that, perhaps she’s from the local Board of Orphans and might find out Miss Hannigan, despite her polite persona, has exploited and abused her charges. In fact, Miss Hannigan gives credence to this theory, assuming Miss Farrell is on the Board and has shown up to interrogate her about Annie running away.

The truth is better–or worse–than the orphans or Hannigan imagined. Grace Farrell is the private secretary to local billionaire Oliver Warbucks, who has garnered the negative image of a cold, callous businessman (and a Republican, as the 1982 film points out–the party of President Herbert Hoover, who was blamed for the Depression). Grace, as she insists Miss Hannigan call her, has come to Annie’s orphanage seeking a child who could stay with Warbucks for a while (over Christmas in the original musical and 1999 film; a “normal” week in the 1982 version, and indefinitely in the 2014 version). The idea is, the presence of an orphan would soften Warbucks’ image and give him someone and something to focus on other than work. Additionally, all versions imply Annie’s presence would help Warbucks’ political career to some degree.

Although Hannigan practically salivates at getting any connection to a billionaire, she’s not willing to let Annie take the opportunity Grace offers. Exactly why is unclear. She may have singled out Annie as a special target for punishment or, as some fans claim, might have a level of fondness for Annie that she’s unable or unwilling to show. Whatever the case, Grace convinces Hannigan to release Annie, subtly threatening her job and citing the circumstances of the Depression as a reason Hannigan shouldn’t cross her. Grace also sees to Annie’s immediate physical and emotional needs, assuring her Sandy can come to Mr. Warbucks’ house with her, and they will stop off at Bergdorf’s to buy a coat. When Annie and Grace arrive at the Warbucks mansion, Annie shows immediate enthusiasm at the idea of “a bath, all for me,” and licks her lips in anticipation of a not only adequate, but sumptuous meal. She’s bewildered yet grateful when Grace clarifies she is at Warbucks’ house as a guest, not a maid (Marshall 1999).

In the space of hours, Annie has exchanged extreme hardship for extreme luxury. Not only is she no longer a servant, she’s the one being served, thanks to a house full of staff who immediately dote on her. Not only does she escape cold and starvation, she will get the best food, clothing, and accommodations her city can offer. Annie has not only escaped the realities of Depression-era NYC. It seems she’s been completely removed from them, as far as she can physically get.

Annie’s reversed fortunes address her emotional poverty, too. Warbucks initially rejects her, insisting he wanted a boy. In his view, “orphans are boys,” and viewers can infer Warbucks expected he’d build better rapport with a male (Huston 1982). Thanks to Grace’s pleas and the staff’s dedication though, Warbucks agrees to let Annie stay for the prescribed period. As befits the idealized world of a musical, he quickly grows attached to his new ward. Annie’s sunny personality sways him, as does her straightforward outlook on life. For instance, on hearing Warbucks wanted a boy, Annie doesn’t break down. Instead, she says, “That’s okay…it was nice meeting you anyhow.” She adds, “It’s a…terrific idea…to invite an orphan for a week, Mr. Warbucks. Even if I’m not the orphan, I’m glad you’re doing it” (Huston 1982).

Upon seeing how thrilled Annie is with an outing to the movies–something Warbucks took for granted–the billionaire is permanently charmed. He still acts awkward at tender moments, such as when he tries to put a sleepy Annie to bed and needs Grace’s help. He’s also not ready to “keep” Annie yet (read: commit to adoption), although Grace and the staff are all for it. Yet the musical and film adaptations make sure viewers see Warbucks and Annie growing into an authentic father-daughter relationship. Both forms spend a lot of time on Warbucks’ response, highlighting how lonely his pre-Annie life has been. The musical uses the solo “Something Was Missing,” while the historically-based films focus on Warbucks’ own history as a poor English orphan. Both situations give Warbucks and Annie common ground, and help viewers believe Warbucks could be a devoted “daddy” to the little girl.

If Annie ended here, it would still be a great example of a New York-sized dream coming true for a heroine who “earned her happy ending” through tough, yet charming, New York-style grit (TV Tropes). But the musical and adaptations take the plot a few steps further, bringing the reality of Annie’s hardships back into focus. That is, Warbucks eventually agrees to adopt her, meaning her physical and emotional poverty will stay in the past. But Annie isn’t ready. She recognizes even Daddy Warbucks, who has “been nicer to me than anybody in the whole wide world,” can’t fill her real hunger, her heart’s real hole (Huston 1982).

When Warbucks probes, he learns Annie’s parents didn’t simply die. Like thousands of other parents, they gave her up when she was a baby. True to form, Annie has built up ten years of hope that they’ll reclaim her someday. She explains she can’t accept the engraved locket Warbucks offers as an adoption gift because her broken one is the only proof she has biological parents. Annie’s parents left a note promising to return for her when able, and took the other half of the locket as proof their claim on her. “I just gotta find them,” she tells Warbucks, who’s immediately on board. “Then I’ll help you,” he promises, indicating he has learned to hope as tirelessly as Annie has (Huston 1982). And since Annie’s dreams have panned out so far, it seems prospective father and daughter are thinking, why not go for broke?

Go for broke they do, with Warbucks putting his plethora of resources behind finding Annie’s biological parents. The stage play references an “open call” and $50,000 reward to the couple who can corroborate Annie’s story. The historical film adaptations actually show the ensuing frenzy, and the 1982 film adds an impromptu visit to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who becomes one of Annie’s most ardent supporters. This time though, Warbucks’ “golden touch” runs out, along with Annie’s optimism.

Miss Hannigan unites with her scheming brother Rooster and Rooster’s girlfriend Lily to get their hands on the reward and dispose of Annie. Specifically, Rooster and Lily will pass themselves off as Annie’s parents, while Hannigan takes a cut of the money in exchange for keeping Annie captive and cowed until the group can “drop her in the river” (Huston 1982). Hannigan gives Rooster and Lily the other half of Annie’s locket, plus a partially forged birth certificate, to ensure the plan’s success.

Thanks to Annie’s fellow orphans and the determination of Warbucks and Grace, the kidnapping scheme is foiled. The film adaptations expand this into a full-fledged rescue, but in the original musical, Annie is literally saved minutes after the villainous trio shows up to claim her. The musical also adds another cameo from President Roosevelt, who’s been invited to Christmas dinner, has Hannigan and Co. arrested on the spot, and promises all Annie’s friends will be adopted. The ultimate happy ending ensues, with Annie accepting Warbucks as “Daddy” forever, and everyone guaranteed a merry Christmas (or perfect life in the 1982 film, which makes no mention of the holiday). The musical and 1999 film even tie up the issue of Annie’s origins with Christmas bows. Her parents are in fact dead, but were killed in a fire; they never meant to abandon their daughter permanently. Better, they have solid identities–David and Margaret Bennett–and Warbucks assures Annie she can take their name as well as his, becoming Annie Bennett-Warbucks.

By the time the curtain closes on Annie, our heroine has transformed in every way possible. She’s retained the “best” parts of her Orphan’s Ordeal, such as how it shaped her character (TV Tropes). But now, she is much more than one of NYC’s 200,000 “vagrant children.” If anything, she is a NYC princess, the centerpiece of a perfect fairy tale. She is Cinderella, but an improved version: younger, more innocent, and able to withstand higher levels of hardship and disappointment (ex.: holding out hope for living parents and adjusting to the latent truth of their deaths, rather than accepting orphan status immediately). In Annie Bennett-Warbucks, musical fans get a taste of the most idealized New York City spirit, and success story, Broadway could offer.

Annie as a Microcosm

Annie’s new “princess” status leads some viewers to dismiss her story as too perfect. This is especially true since starting in 1982, American viewers were at least 50 years–almost two generations–removed from the Great Depression. Instead, they faced their eras’ travails, from new economic problems to crime, drug use, the dark side of technology, and a global pandemic. Orphans still existed and, thanks to increased legal and charitable oversight, were in less danger of villains like Miss Hannigan. Yet, the American foster system remained broken, and many kids like Annie now faced the possibility of much less sanitized abuse from “caregivers.” Such abuse might include ongoing neglect, severe and disabling beatings, or even human trafficking. Thus, viewers ridiculed Annie as sappy and perhaps dangerously unrealistic. This writer grew up with parents who grew weary of her belting out the songs and playing at being the titular redhead. This was mostly because underneath, they were wary of the musical’s message for a sheltered kid who had no clue what real, modern orphan status looked like.

Yet this writer grew past these concerns, and other viewers can, too. If anything, they should. Annie’s story is idealized, probably because the Cinderella-esque plot plays so well to the little kids in the target audience. But under its sanitized exploration of orphan-hood and ideal portrait of adoption, Annie hides a deeper layer. The production, and the character herself, serve as microcosms for how real people endure hardship, learn, and grow stronger. American history teaches us trials, whether on a national scale like the Depression or a personal scale like a rough childhood, can never be avoided. Additionally, real people can’t sing their way out of problems or keep up Annie’s unfailing positivity forever. But whether or not Annie’s story can be imitated is not the point. The point is that Annie and her story represent more than ideal circumstances. They represent the union of grit and glitter, the idea that as long as tomorrow comes, it might be better than yesterday or today.

Annie encapsulates not only the reality of her time period, but the reality of any era and hardship in which her fans may find themselves. Her physical lack may not be as common or easily seen in the 21st century, but it’s a microcosm for the experience of not having what you need, or feeling unworthy to receive it. For instance, a 21st century kid living in a poor neighborhood may in fact wonder where the next meal is coming from. A single mother might not have to abandon her kids to an orphanage, but may wonder, can she provide for them adequately? Will they have the chance to live grown-up dreams, or will financial realities quash those dreams? A minority group member may work as hard as possible, but run into discrimination and microaggressions every day. Someone struggling with any kind of eating disorder might feel unworthy to partake in the basic ritual of eating, or be told they are unworthy because they partake too much.

As for Annie’s emotional lack, that’s more of a microcosm now than it has perhaps ever been. That is, today’s orphans or foster kids are much more likely than Annie to know their parents’ names and histories, or at least names. They are more likely to enter the social welfare system based on their parents’ personal hardships, not necessarily financial trouble or the death of both parents. Yet those orphans are perhaps more likely than Annie to feel lonely, disconnected, and unwanted.

Annie fans who have never been orphaned can still find a piece of her microcosm with which to identify. Those fans may have experienced bullying and ostracism as children, struggle to find meaningful connections as adults, or grapple with emotional or spiritual holes that remain unfilled. They may have lost people or pets who felt as dear as parents, or endured situations that demanded they forget about “tomorrow” in favor of surviving “today.” Yesterday may have well been “plain awful” because of any number of traumas–traumas that, like Hannigan, use inner lies and manipulation to keep these fans trapped in the “orphanage” of the past.

In light of this microcosm, the perfect realization of Annie’s dreams becomes the first stage of the human spirit’s growth. It starts out in a difficult, gritty, yet still sanitized version of its own “New York City,” where liberal doses of optimism ensure it won’t give up. It reaches toward a dream like Annie’s, and eventually learns that dream may not be reachable, or if it is, will look different than previously anticipated. But in the “Annie stage,” the human spirit learns to navigate “New York City” without succumbing to despair. The “Annie stage” encourages healthy escapism and idealization for the sake of mental health. It recognizes this stage is one humans must pass through in preparation for harder trials and “rougher neighborhoods.” Annie becomes the first, safe experience of grit and glitter for the child dreamers in its audience. It becomes the place of respite for adults who may have let go of Daddy Warbucks, but need reminders that tomorrow could always be the best day yet.

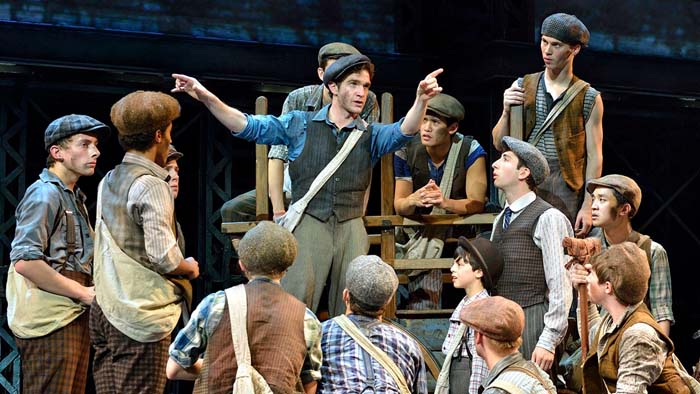

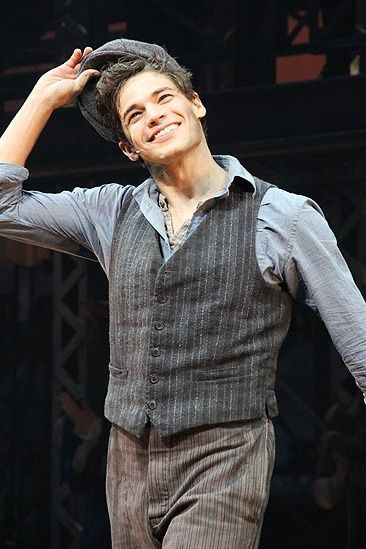

Newsies

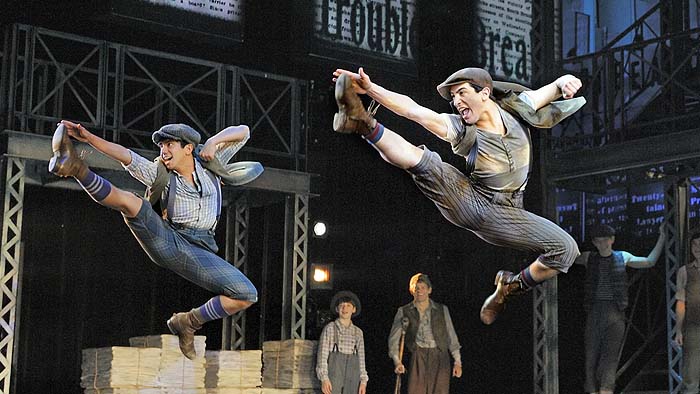

Based on its origins, Newsies sounds like the opposite of a New York City musical honoring the human spirit. It began as a musical, but not on Broadway. Instead, Newsies was a 1992 Disney movie musical that bombed at the box office. Viewers couldn’t get past the incongruity of “Disney” and “musical” being associated with an 1899 newsboys’ strike, a real historical event focused on some of the worst examples of child labor and exploitation. Christian Bale, who played lead newsboy (newsie) Jack Kelly, has been said to regret his role in the film, and most of the child actors who played the other newsies are now relatively unknown. Newsies seemed destined for the dustbin of film history, or perhaps worse, a place on lists like “Top Ten Worst” or “Top Ten Most Forgotten Films of the ’90s.”

Twenty years later, Newsies shocked–if not stopped–the film and especially theater worlds when it resurrected. Circa 2012, Alan Menken, who had written music for such Disney hits as The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin, got together with Harvey Fierstein to write a new book for the Newsies musical. Fierstein and Menken made several major changes to the original story. Protagonist Jack Kelly received more character development, including deeper artistic talent and compassion-driven angst. Reporter Brian Denton, who wrote the article that garnered huge support for the newsies’ strike in the 1992 film, was replaced with spunky female reporter Katherine Plumber. Katherine also took the place of Sarah Jacobs, Jack’s film love interest who read more as a token than a girl with personality. Jack’s friend Crutchie, so nicknamed because he uses a crutch to support a polio-weakened leg, received a bit more character development and a crucial Act II solo.

These and other, minor alterations readied Newsies for its first run at the Paper Mill Playhouse, New Jersey’s state theater. The production was intended for a short run, just long enough to encourage licensing for high school and other community productions (TV Tropes). However, Newsies garnered several Tony nominations, winning for Best Choreography and Best Original Score (Newsies Wikipedia). Alan Menken and choreographer Christopher Gattelli won Drama Desk awards for Best Music and Outstanding Choreography (Newsies Wikipedia). As a result, Disney authorized Newsies to appear on Broadway for a 1000-show run. The hit production was televised, and now it, along with the original 1992 film, can be streamed on Disney+. Both cast recordings are available on iTunes and other streaming services, and social media bursts with fans known as “Fansies.”

On the surface, Newsies looks completely different from Annie, from its “underdog” media history to its older male protagonist, from its higher-stakes plot to its more sophisticated songs and choreography. However, just as the newsies call themselves “brothers” and “family,” the production acts like an older sibling or cousin to Annie, in content if not production date. Newsies holds onto Annie’s commitment to hope and the human spirit. Yet, it throws fresh, harder challenges at those underpinnings. It calls on viewers to examine how fictional characters and real people should respond when maintaining a strong spirit becomes more difficult.

Newsies as a Survival Story

To the modern audience, Newsies’ premise might seem as simple, and silly as the explanation of the original film did in 1992. After all, why would filmmakers or theater directors tell a story about a newsboys’ strike as a family-friendly musical? The implication is that real labor strikes shouldn’t be taken seriously. If anything, they’re fun and exciting. However, people who doubt the seriousness of Newsies don’t have to look far to find the gravitas under its Broadway and Disney glitter.

The slightest dive into the history behind Newsies reveals that the life of an 1899 newsboy (or less commonly, but not rarely, newsgirl), was not exactly “a fine life carrying the banner” as Alan Menken put it. “Carrying the banner” was actually slang for sleeping on the street, which many if not most newsies did, because although lodging houses were available, those places charged rent. Newsies have been described as “wretchedly poor, homeless children” who “shrieked headlines well into the night.” The average newsie made about 30 cents per day from selling papers at two for a penny.

As the song “Carrying the Banner” explains, the newsies were required to buy back any unsold papers at full price. Assuming a newsie paid for lodging house rent, plus three meals per day, his or her “take home pay” was likely less than half of the average 30 cents. Incidentals were out of the question–and according to James B. McKay, incidentals could include such basics as coats and shoes. The picture of 19th-century newsies “surrounding you on the street and almost forcing you to buy their papers” hardly matches the musical’s rosy picture of rough, but innocent urchins trying to make a little pocket change.

That said, knowledge of newsie history does add needed weight and empathy to the fictionalized story of Jack Kelly and friends. When viewers hear that Joseph Pulitzer has raised the price of papers by a dime, yet still expects newsies to pay full price for what they don’t sell, those viewers won’t wonder why these boys (and presumably girls) are complaining about spending an extra ten cents. They may not even chalk Pulitzer up as a Disney villain, a “rich, greedy sourpuss” (Newsies 2012 track 8). Instead, they will understand the newsies are a labor force fighting for survival. Thus, Pulitzer, Hearst, and the other “muckety-mucks” of NYC have committed a much bigger crime than taking dimes from kids, or “taking candy from a baby,” so to speak (Newsies 2012 track 11).

If anything, the fact that the newsies are kids–mostly teenagers, but still minors–makes the audience root for them harder. In Jack Kelly, an orphan who watched NYC’s “bosses” “break [his] old man,” a kid who dreams of getting out but can’t, the audience may see themselves as they once were or feel they still are inside (Calhoun 2012). So when Jack declares Manhattan’s newsies are on strike, the audience cheers him on.

Most viewers have probably not participated in a labor strike, or if they have, it was probably much better organized and safer. Hopefully, most viewers haven’t endured flagrant workplace abuse, or poverty at a newsie’s level. However, most Newsies fans can point to a “Pulitzer” in their lives, someone who mistreated, discriminated against, or cheated them, yet got away with it because of power and authority. Maybe they weren’t able to fight these oppressors. Maybe they didn’t feel the injustices they faced were worth a fight. However, seeing the newsies’ strike reminds viewers, some things are worth the fight. As Katherine Plumber puts it, “life’s little guys…just might win” (Newsies 2012 track 8).

Newsies as a Family Story

Jack Kelly may be the newsies’ leader, and he may have decided the strike was worth the fight, but he doesn’t go into it alone. A labor strike’s nature means he can’t succeed alone. But more importantly, Jack refuses to strike without support or camaraderie, because doing so means leaving his newsie “brothers” behind. “Don’t you know that we’s a family?” Jack asks Crutchie in the production’s first song, “Santa Fe.” “Would I let you down? No way,” he goes on (Newsies 2012 track 1). He and the other newsies repeat this “family” sentiment throughout the show, in actions more than words. With the exception of Davey and Les Jacobs, none of them have biological families able or willing to provide for them. Thus, “brotherhood” must hold the newsies together physically and emotionally. It must form the backbone of their reason to continue striking even when no one around them offers support.

What begins as Jack Kelly’s individual voice proclaiming, “They ain’t [breakin’] me,” becomes a collection of voices and spirits declaring, “Pulitzer may own the World, but he don’t own us!” (Newsies 2012 track 7). The “me” of Jack’s longing for Santa Fe becomes the “us” of NYC in the present moment. Jack has said “no” to NYC’s browbeating all his life, but once the newsies’ strike begins, his brothers have a concrete reason to join him. If the World says “no” to something as small as fair pay for a few sheets of paper, well, the kids selling those papers can say “no,” too. And while Pulitzer, his corporation, and his power might take down one newsie, they might well think twice about crossing the whole family.

Getting to know Jack and his newsie family gives viewers fully realized people to support within the context of a labor strike, where participants might otherwise be faceless and nameless. During Newsies, viewers come to love Davey and Les as more than “the new kids.” They’re two sheltered and naive, but courageous, boys who’ve never experienced close friendships or taken risks, because their parents and siblings required all their energy. Within the strike, both boys grow into true companions for the other newsies, willing to take risks and sacrifice comfort for the good of the “team.”

Similarly, viewers learn Crutchie is more than the “Token [Disabled] Teammate” (TV Tropes). He is optimistic and upbeat, but uses his “smile that spreads like buttah” to hide ever-increasing worries about his future as a “crip” in a majority-abled world (Calhoun 2012, Ortega 1992). Those worries and that sunny personality make Crutchie the “little brother” the newsies, especially Jack, tend to protect. But viewers get behind Crutchie and his role in the strike because he’s also adamant that his personality sets him apart, not his crutch. He can flirt and fib to sell papers, often better than his brothers do. Antagonists like the Delancey brothers may try to beat him up, and will succeed because Crutchie is smaller and easier to pick on. But in the process, they may well get a deserved crutch to the kneecaps.

With these personalities fleshed out, and more adding shading to the family (Race, the chain-smoking “bad boy with a good heart,” Romeo the flirt, Henry the foodie, Specs the smart and plucky guy with glasses), viewers start to feel like they’re not just watching a strike on stage. They’re part of the newsie family too, watching and supporting everyone’s character growth. These boys are so engaging, and play so well off each other, that the fandom has expanded their characters and arcs where the original scripts did not. Just from hearing the songs, fans care about everyday newsie matters. They ask questions like, “Did Elmer ever get that half a cup [of coffee?]” “Did Romeo find an angle?” or, “Did Specs ever find his shoe?”

Most of these questions are meant as funny, like miniature headcanons. Again though, they read a bit differently if one takes into account that if a newsie fails to “find an angle,” he can’t sell papers, or doesn’t have shoes period if he loses one. Viewers engage in the strike not only because they want the newsies to win, but because they want good lives for them. These boys are “theirs” now, the epitome of fictional characters taken into real hearts. They probably won’t be “rescued” from the hardships of newsie life as Annie was from Miss Hannigan’s. However, winning the strike means winning a chance at a life focused on something other than survival. Instead, the newsies can focus on kinship and helping each other achieve Santa Fe-sized dreams.

Newsies as a War Story

Most musical viewers are familiar with survival and family, no matter how privileged their lives have been. However, they can get those themes from “softer” NYC musicals like Annie. What sets Newsies apart as the “older,” more mature “sibling” of Annie, what makes its human spirit stronger, is that it is a war story.

Here, “war story” is not meant in the classic sense (though some fans have pointed out the 1899 timeline means, most of the newsies will be old enough to serve in World War I and may not come home). And although the newsies’ strike gets vicious thanks to police and strike-breakers, no bullets are fired. Newsies throw punches, kicks, and other moves–and get battered themselves–but it’s not combat. In Newsies’ context, “war story” refers to the emotional and mental war Jack and his fellow newsies must fight to win the strike. Thus far, these kids have had to save, scrape, and “beg for bread to survive,” but they accepted it as the way life worked (Newsies 2012 track 16). During the strike, the newsies are challenged to their emotional cores. They’ve always accepted poverty, ignorance, and maltreatment, but do they have to? Can Santa Fe “be real…not just some painting in [Jack’s] head?” (Newsies 2012 track 10). If they let the price hike go this time, what happens next time, and if they fight now, will there be a “next time” for any of them?

At first, the newsies think the answers are obvious and the strike easily won. “The World Will Know” and “Seize the Day” encapsulate this in heart-stirring, courageous lyrics, sharp choreography, and music that makes anyone who’s ever felt like a stepped on “little guy” want to scale a statue. The newsies proclaim they will “break the will of mighty Bill and Joe,” “kick rear,” and “stomp all over” the newspaper tycoons who’ve walked all over them (Newsies 2012 track 7). And viewers absolutely believe they will do it, in relatively short order. But just as the reality of combat soon sets in for new recruits, it’s not until the newsies face some real consequences that they learn what they’re fighting for and if they’re ready to go to war for it.

The musical’s tone turns dark at the most unexpected and demoralizing place. After Davey Jacobs leads a rollicking “Seize the Day,” the newsies break into the newspaper circulation center, stage a full protest, and cause havoc. It’s great for a while; the boys enjoy the chaos, camaraderie, and opportunity to let off steam. They’re not fazed when the cops arrive; in fact, Romeo assumes the police are there to help. But instead, they’re there to break up the protest, and many newsies are injured. Worse, Mr. Snyder, the warden of an orphanage and prison called the Refuge, shows up and arrests Crutchie, after beating him black and blue with his own crutch. Unable to run or fight back, Crutchie is the only newsie who can’t escape the circulation center and is dragged off to the Refuge, presumably forever.

The other newsies seem willing to let Crutchie’s arrest go for the moment. As Davey says early in Act II, “Lighten up, no one died,” and “We’re already winning…we got them surrounded!” But Jack is demoralized and ready to give up on the strike and New York. His reprise of “Santa Fe” shows him wracked with guilt over not helping the newsie he considered a closer brother than anyone else. Later, he confronts Davey with reality–“They busted [Crutchie] up so bad…what if he don’t make it? Are you willing to shoulder that for a tenth of a penny a pape?” (Calhoun 2012). Indeed, death is a distinct possibility for Crutchie, whose then-incurable polio might resurface in the abusive environment of the Refuge–a place riddled with vermin, where three boys sleep to a bed. Once Jack expresses this, the other newsies aren’t so keen to get back on the picket line.

The newsies’ future turns darker when Jack is called into Pulitzer’s office to settle. There, he learns Katherine, the strike’s biggest supporter and his new love interest, is Pulitzer’s daughter and apparently double-crossed him. Worse, Pulitzer and Snyder threaten to have every newsie–including Davey and Les, whose parents are alive and newly impoverished–thrown into the Refuge if Jack doesn’t stop the strike. Twisting the knife, Pulitzer offers Jack blood money. If he takes it, he can go to Santa Fe and live in peace, a free man. Otherwise, he will join his friends in the Refuge and, it is implied, determine how much abuse his brothers suffer based on his cooperation. Heartbroken over Katherine’s alleged betrayal, and in possession of a letter that sounds like Crutchie’s last request, Jack agrees to “scab” for Pulitzer and rally the newsies to end the strike. He is simultaneously a turncoat and a prisoner of war.

At this point, viewers have not just joined a labor strike. They are in the trenches with the newsies, fully cognizant of the stakes. Newspapers and money don’t matter any longer. The strike must be won, or every newsie becomes an emotional, likely physical, casualty. Moreover, they cannot win without Jack, who must now face a truth that threatens to gut him. Santa Fe, the place and the concept of getting out of NYC, was a worthy dream at first. However, it has become a mental escape, nothing more than an image. It has insulated Jack from his personhood as a newsie, New Yorker, and human being. The Santa Fe dream is so nebulous and fragile, it’s actually crushed Jack’s spirit. Plus, sharing it with other newsies like Crutchie, as if it was their dream too, has endangered their spirits. The strike trenches are filled with broken bodies and hearts, and the platoon captain is AWOL.

Newsies as a Microcosm

As Jack wrestles with the choice to run or stay, turn traitor or stand with his brothers, viewers find a microcosm as they did with Annie. But in Newsies, the microcosm does not hinge on keeping an upbeat spirit and dreaming of better tomorrows, on the chance they will come. The call to nurture the human spirit still exists, but now it acknowledges, “Santa Fe’s great, but it may not materialize. Winning against a personal Pulitzer, Hearst, Snyder, or Hannigan takes guts, maybe without the glory or front-page story. If you want to win, you have to grow up, stand tall, and finish what you start.”

Viewers will all recognize this moment in Jack, Katherine, Davey, or even some of the background newsies who don’t get many lines but feel like the kids viewers used to be. Disabled or not, they can even find this moment in Crutchie, who acknowledges the Refuge may be his final future, but stands with the newsies, pleading not to get out, but for “all the fellas…to protect one another.” Viewers mourn with the newsies as they realize, Pulitzer, Hearst, and Snyder are still powerful, especially as a combined force. The newsies may still lose the strike if Jack returns, and even if not, no Daddy Warbucks will lift every one of them from poverty. Sure, supporters like Katherine, famous actress Medda Larkin, or Governor Teddy Roosevelt may lend support. Still, the papers don’t sell themselves, and child labor laws as 21st-century viewers know them are still a ways off. Even if Jack could reach Santa Fe, ranching life would probably break him, just in a different way than NYC did his dad. Even if Crutchie does escape the Refuge, he’s still disabled in an era with no Americans with Disabilities Act, therefore, few opportunities.

As they mourn though, viewers can find the other side of the Newsies microcosm in hope. When Jack returns to the strike and Brooklyn’s newsie “king” Spot Conlon brings in a tidal wave of support, viewers see themselves again. They remember times when they, like Jack, were demoralized and unable to pick themselves up, physically or emotionally. They may remember times when they made the childish or selfish decision and in doing so, hurt others. Some viewers might remember emotional casualties of their personal wars, their personal decisions, they can never reclaim. However, seeing Jack, Davey, Katherine and the others rejoin the strike and proclaim “this time [they’re] in it to stay,” reminds viewers the past doesn’t have to define them (Newsies 2012 track 16). It can’t be undone, as Davey says, but moving on doesn’t mean letting yourself or your support system become collateral damage. Indeed, Jack can only celebrate victory when Crutchie is freed, Snyder arrested, and the other newsies back on his side. He can only grow into the next phase of his life, his spirit, when he hears Katherine out and agrees to trust her again.

Most Newsies fans won’t get the perfect ending Jack gets. Most won’t face the clear-cut choices he does, making their decisions harder and more life-altering. Most fans will find that sometimes, the Pulitzers and Snyders of the world “win,” or if not, cannot be shoved in a jail cell, held to an ironclad contract, or otherwise avoided. But Newsies gives musical fans the tools and the strength to move from their Annie stage to their Newsies stage. Unlike the Annie stage, which focuses mostly on innocence and dreams, and usually has a finite end, the Newsies stage is more fluid. It gives the human spirit more room to grow. This stage may not always be safe; viewers can enter and leave it depending on the maturity and wisdom of their choices. But Newsies doesn’t stop at cheering for the good and the ideal like Annie does. This stage makes a place for the hard road a human spirit must travel. It makes room for our “scab” moments and says, “You can grow past this. Mourn, bury what no longer fits, and try again tomorrow.”

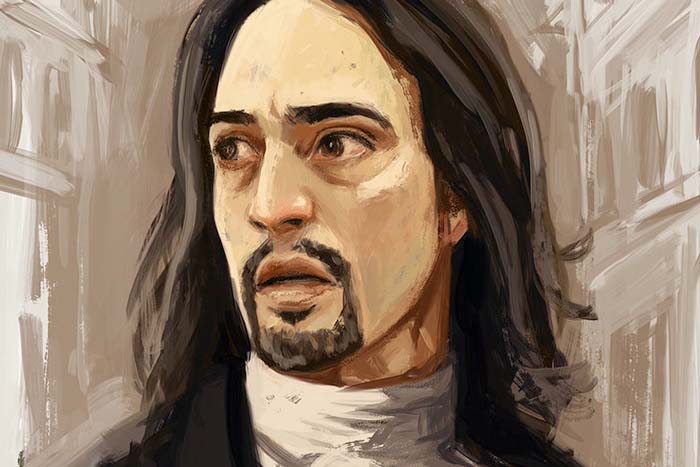

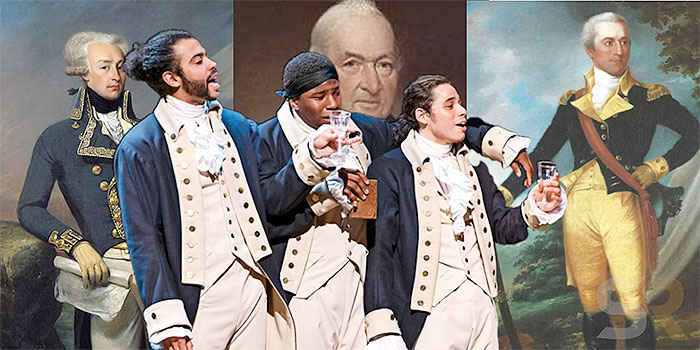

Hamilton

In 2015, Lin-Manuel Miranda gave the United States, and later the world, Hamilton, a historical epic musical based on the eponymous Founding Father. Like Newsies, its premise seemed odd and shaky at first. Not many people knew much about Alexander Hamilton, and the information they had probably came from history class, not entertainment. Additionally, Broadway had hosted historical musicals before, such as 1776, which takes place in Hamilton’s era and focuses on better-known figures and events. Yet that musical never garnered a big or vocal fanbase.

Unlike 1776 or Newsies, however, Hamilton was an almost instant hit. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s commitment to giving a long-dead Founding Father’s life the hip-hop musical treatment pulled in scores of fans who might turn up their noses at a traditional musical. The musical’s monster soundtrack–46 songs, 2 hours and 23 minutes–has sold almost 2 million copies in the U.S. alone. The show is set to reopen on Broadway September 14, 2022 after closing due to COVID-19 restrictions, and is currently playing in other states such as North Carolina (Charlotte) and Tennessee (Knoxville). Hamilton has streamed on Disney+ since July 2020, and merchandise of all shapes and sizes is available online. During the pandemic, this writer sported her own Schuyler Sisters-inspired “Rise Up” mask.

Interestingly, Hamilton doesn’t read as a NYC musical the way Newsies or Annie do. Part of why lies in its time period. In the 1770s-’80s, New York State was only about 150 years old, an original colony. New York City was a bustling metropolis; Angelica, Eliza, and Peggy Schuyler sing it is “the greatest city in the world” during the show (Hamilton 2016 track 5). However, NYC wasn’t the city modern musical fans know. For instance, the Statue of Liberty wouldn’t arrive in its harbor until 1876, a century after Alexander Hamilton’s time period. Times Square wouldn’t be created until 1924. And although the show’s Alexander Hamilton is told, “In New York, you can be a new man,” he would be relatively unknown for centuries, almost unknown to most modern Americans, and not one of NYC’s most famous figures.

This said, Hamilton the show more than earns its place as a historical NYC musical speaking to the human spirit. It focuses much more on Alexander Hamilton than the city he lives in, but this works for the type of musical it is and its place in our discussion. Thus far, we have discussed how NYC historical musicals show viewers how to navigate their personal versions of New York, grit, glitter, and all. Hamilton presents NYC as the experiences, memories, defeats, and heartbreak a human spirit takes with it everywhere. This musical answers the question, “How does a human spirit make a mark, leave a true legacy, when not just NYC, but the world, wants the same thing?” Also, Hamilton pushes the NYC historical musical further than it has ever gone, challenging it with the question, “What is a human spirit? What makes us human? Who lives, dies, and tells our story, and what makes that story worthy to be told?”

Hamilton as a Hero’s Journey

More than our other two musicals, Hamilton is a hero’s journey. Annie Bennett Warbucks, Jack Kelly, and their peers are heroes and heroines for sure, but Alexander Hamilton’s story reads the most like a true “hero’s journey” or “monomyth” as defined in literature. Broadly defined, this journey has a “separation,” where the hero sets out on a journey or adventure, an “initiation” where the hero “arrives” inside the adventure, and a “return,” where the hero finishes his or her journey and must often literally return home. We see this with Alexander Hamilton in the eponymous musical as he leaves for New York to “be a new man,” is “initiated” into life as a revolutionary, and returns after decades of working to obtain his legacy. Hamilton’s journey encompasses everything from revolution, to combat, to love, to infidelity and betrayal. It spans the kind of timeline usually found in an epic poem or story, and focuses much more on the hero’s inner growth than external stakes. As Hamilton lives a “monomyth” story, he almost becomes a mythic figure onstage, showing viewers everything from ambition and triumph to defeat based on tragic flaws.

But what makes Hamilton a better character, and Hamilton a better story, than an ancient myth is that Alexander Hamilton is a wholly human, fallible man. He’s an adult, but still calls himself an “orphan” as Annie and most of Newsies’ kids did. He even adds “bastard” and “son of a whore,” indicating he has no illusions about his reality, including the hardscrabble nature of his existence or the fact that he spent his childhood unwanted and passed around (Hamilton 2015 track 1). Hamilton later admits he’s “got a lot of brains but no polish” and doesn’t have much to recommend him, not even “a gun to brandish” (Hamilton 2015 track 3). Hamilton maintains this status throughout Act I; Angelica Schuyler notes “he’s penniless” twice, and he tells eventual wife Eliza he has no land, no troops, and no fame (Hamilton 2015 track 11).

The difference between Hamilton and our other orphans though, is that he doesn’t invite pity or even sympathy. He tells viewers he’s “a diamond in the rough,” determined to reach his goals (Hamilton 2015 track 3). An adult, Hamilton has nothing to fear from abusive caretakers or institutions. He doesn’t depend on adoption or family structures to “grow him up.” He’s already primed for heroism, sees his shot at it, and refuses to throw it away. Thus, Hamilton, more than our other protagonists, inspires identification in real time instead of nostalgia. He shows viewers what they could be and inspires them to consider what they must do today, to make that happen.

Alexander Hamilton as a Tragic Hero

Additionally, Alexander Hamilton and his musical are human because they show us flaws, failures, and recovery of a hero more than Annie or Newsies. Annie Bennett Warbucks had no flaws to speak of. She was acted upon throughout her story, a complete innocent who invited mostly pathos from the audience. While you could call her desire for “real” parents even as she lived in Warbucks’ luxury selfish, it’s more than understandable since Annie had no knowledge of her background, so it’s not a real flaw. Similarly, Jack Kelly showed viewers flaws, including selfishness, obliviousness to others’ struggles, a hot temper, and reliance on escapism. But considering Jack got everything he wanted in the end and is assumed to “live happily ever after,” his flaws don’t read as integral to his story or personhood.

Alexander Hamilton is a completely different, better realized protagonist. His flaws are expertly mixed with his strengths and apparent almost from Act I, scene i. Hamilton admits, “Sometimes I get over-excited/shoot off at the mouth” and is ready to grab ammunition and go to war while his new revolutionary friends Laurens, Mulligan, and Lafayette are still planning what the revolution will look like (Hamilton 2015 track 3). Later on, Hamilton gets into a duel with fellow soldier Charles Lee, calling him “inexperienced and ruinous” without considering Lee’s point of view (Hamilton 2015 track 15).

Even in Act II, when the American Revolution is over, Hamilton is justly accused of never shutting up, to the point of “[talking] for six hours” at the first Constitutional Convention and overplaying his hand in cases where he serves as defense attorney. His marriage suffers because he is a “non-stop” workaholic, “never…satisfied” (Hamilton 2015 track 23). In her cut song “Congratulations,” Angelica tells Hamilton his problem is that he “[dignifies] schoolyard taunts with a response” and is his own worst enemy. Indeed, Hamilton is an expert bridge-burner, once accusing Thomas Jefferson of being “out of your [damn] mind” and calling James Madison “mad as a hatter” and “useless.” (Hamilton 2015 tracks 25 and 30).

These flaws not only persist throughout the musical, but worsen, clouding Hamilton’s judgment and threatening to ruin his personal and professional lives. When Jefferson and Madison accuse him of financial misconduct, for instance, it’s not enough for Hamilton to provide an alibi. Instead, he publishes the intimate details of his affair with Mariah Reynolds, shaming Eliza and almost killing the marriage. “In clearing your name, you have ruined our lives,” Eliza accuses her husband in her solo “Burn” (Hamilton 2015 track 37). She goes on to declare, “You forfeit all rights to my heart” and “I’m burning the memories, burning the letters, that might have redeemed you” (Hamilton 2015 track 37). It takes the loss of his oldest son, in a foolish duel much like the one his father experienced, for Hamilton to recoup any losses.

In a NYC musical like Annie or Newsies, Alexander Hamilton’s story would have ended here, showing him as a fully redeemed hero whose life will become perfect. Hamilton’s trajectory does improve after Philip Hamilton’s loss. Eliza forgives him, and he tries to resurrect his political career. But a combination of grief, depression, pride, and ambition take him down again. After the 1803 election, John Adams becomes President, and Hamilton loses contact with his mentor and father figure, George Washington. Jefferson and Madison now have carte blanche to gloat over Hamilton’s failures–“Washington can’t help you now, no more Mr. Nice President” (Hamilton 2015 track 34). With his own shot at the presidency blown thanks to the revealing of his affair, Hamilton is a prime target for fear of his enemies’ actions to ruin his life. He throws away his last shot, figuratively and literally, when he’s killed in the historic duel against longtime rival Aaron Burr.

Alexander Hamilton’s end is devastating for viewers because they’ve spent two acts watching him grasp so hard at life and “imagine death so much it feels more like a memory.” Where Jack and Annie’s inner versions of NYC elevated them, Hamilton’s version has subjected him to the worst of itself, through his own pride, ambition, and foolish choices. Unlike Annie or Jack, Hamilton doesn’t read as someone for viewers to support or emulate. In the eyes of some, it may be Hamilton deserved to have “his enemies [destroy] his rep [and] America [forget] him” (Hamilton 2015 track 1).

Yet, viewers stick with and root for Hamilton much more than Annie or Jack, not in spite of his tragic flaws but because of them. They recognize the story’s hero died a broken man and didn’t leave the legacy he craved. Simultaneously though, Hamilton’s story is so compelling, and he is such a multifaceted character, that audiences can forgive him. As the musical progresses, they move from identifying with Hamilton’s humanity to appreciating and mourning a real person, onstage and off. Hamilton, who became a “new man” in New York, connects audiences to their flaws and fears. But as Eliza reveals in the show’s final song, flaws do not make your story or life worthless.

Hamilton as a Microcosm

Alexander Hamilton is so well-developed, and his story so rich and colorful, that he becomes the best microcosm in our discussion. Again, his story is not tied as closely to NYC as Annie Bennett-Warbucks’ or Jack Kelly’s. Yet this works for Hamilton in ways it didn’t work for the other two heroes. Within Hamilton, both the man and the city itself become microcosms for who we were, who we are, and who we can be, if our spirits remain intact.

Like Annie and Newsies, the story of Hamilton focuses a lot on what was for its protagonist. Adult though he may be, Alexander Hamilton is a mental and emotional orphan when we meet him. He’s “never had a group of friends before,” he’s apparently in such financial trouble he’s constantly “famished,” and he has no concrete place to put his ambitions (Hamilton 2015 track 3). Arguably, Hamilton rises above those circumstances more quickly and effectively than Annie or Jack did, gaining a key role in the American Revolution, financial security, a family, and a chance at a political legacy. Yet during the musical, particularly Act II, viewers still find the lost little boy behind Hamilton’s bravado. Hamilton’s choice to cover his fear and insecurity with workaholic tendencies and a hotheaded attitude hearkens back to early America, wherein the flames of the Revolution left uncertainty and confusion in their wake. Audiences sense the aftermath within Hamilton’s NYC, and lean into Hamilton and other characters’ uncertainty as their own.

Hamilton and his musical retain audience support because they don’t stay locked in uncertainty forever. Hamilton doesn’t engage in self-pity, nor does he tell himself tomorrow will be a better day or turn to escapism. Instead, Hamilton’s musical moves from showing audiences who they were–the past versions of themselves they may not like–to who they are. These are the versions Hamilton and his viewers try to build. They are people in the final historical New York musical stage, the Hamilton stage, working on accepting who they are and carving niches that will take them to higher, better places. Alexander Hamilton reminds us such carving must be done carefully. Otherwise, the strongest and most resilient person can burn themselves out. Like Hamilton, they may not come back from that place, even if they don’t die. However, Hamilton reminds us that our stories and the places in which we craft them, our personal NYCs, must be accepted as they are. The sparkle of “tomorrow” or “Santa Fe” may linger for a little while. But to grow our human spirits and legacies to the next level, we must reject sparkle in favor of complete realism. If our choices tarnish our legacies, we must live with that as ever-flawed humans.

Alexander Hamilton, his story, and our other NYC stories do not leave us hopeless, however. Just as Hamilton in particular shows audiences who they were and are, it leaves them with the message of who they can be. Hamilton dies, but his story lives on through Eliza and other loved ones. Eliza, in fact, [“stops] wasting time on tears…[lives] another fifty years” and tells her husband’s story through words and actions, such as the building of NYC’s first orphanage. The nation Hamilton so loved, and the city he called home, live on as well. They blossom into an oft-scarred yet resilient nation and a “young, scrappy, hungry” city, much like Hamilton himself. Hamilton‘s ending reminds us that our stories and legacies may never be “big.” Most of us will not become the prince or princess of a fairy tale like Annie, or take down all our local villains for good, like Jack. Just because we don’t, though, does not mean our stories or lives are worthless. It means our spirits are mere stones in the building of the world’s New York Cities–but vital and valuable ones.

Songs of the Spirit Echo Beyond Broadway

It’s said if someone can make it in New York City, they can make it anywhere. Perhaps nothing captures this sentiment quite like the historical New York City musical. These musicals, more than any others, show audiences what it means to be human, to craft our legacies, to nurture our spirits so they thrive even in the worst circumstances. Annie, Newsies, and Hamilton–a nostalgic classic, a sleeper hit, and a worldwide smash–are an absolute power trio when it comes to these themes. Audiences return to them again and again, not simply for the stories or the music, but because these musicals help them “make it” in their versions of the Big Apple.

More than perhaps any other musical, these three allow audiences not only to identify with the protagonists, but “take off” the characters’ dresses or suits and let them “hang” in their imaginations, trying them on for themselves. As they do, audience members do not necessarily become these characters. Yet, they recognize versions of themselves within Annie, Jack, Alexander, or even secondary characters like Angelica, Eliza, Davey, Crutchie, or Katherine. Audience members find pieces of their own depressions, hardships, or fights against oppression within the “costumes” of these characters. Each return to one of these musicals is an opportunity for an audience member to slip into the costumes again, face those hardships, work on them little by little, and come a bit closer to satisfying resolutions.

Works Cited

Calhoun, Jeff. Newsies. Prod. 2012. Retrieved from Disney+ on September 13, 2022.

“Children and the Great Depression.” Digital History. www.digitalhistory.uh.edu. Retrieved on September 13, 2022.

“Hamilton Wikipedia.” www.wikipedia.org. Retrieved on September 13, 2022.

“Historical Context: Newsies.” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History: History Resources. www.gilderlehrman.org. Retrieved on September 13, 2022.

Huston, John. Annie. Produced 1982. Retrieved from YouTube on September 13, 2022.

Marshall, Robert. Annie. Prod. 1999. Retrieved from YouTube on September 13, 2022.

Menken, Alan. Newsies Soundtrack, Prod. 2012. Retrieved from iTunes on September 13, 2022.

Miranda, Lin-Manuel. Hamilton Soundtrack. Produced 2015. Retrieved from iTunes on September 13, 2022.

Ortega, Kenny. Newsies. Produced 1992. Retrieved from Disney+ on September 13, 2022.

“TV Tropes.” www.tvtropes.org. Retrieved on September 13, 2022.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

When I went to see Newsies show me and my friends were sat in Brooklyn and sat behind us was Matt Cole, the mother of the child actor and main performer who plays Romeo and it was the so insanely surreal.

Oh, so they have different “neighborhoods” where they seat people? Cool! Yeah, gotta love Brooklyn…although if I’m a Manhattan newsie, I’m like, “You just got word? Dude, we told you like, a week ago!”

Ahhh Annie. What’s not to like? Great songs, great production numbers, staging, the good guys win, the bad guys loose, the orpahns are cute, good moral values but not preachy. All tied up in a very pleasant couple of hours. Broadway at it’s best.

It was the first musical I ever saw (1982 version when I was about six). I memorized it to the point of quoting lines/drove my parents crazy. 😉

I LOVE Newsies! Got to see it almost a decade ago on Broadway (January 2013) with most of the original Broadway cast (minus Jeremy Jordan who already left by that point.) Corey Cott had just gotten married so I got to see Mike Faist understudy for Jack Kelly and Ryan Breslin as Davey. I already loved Newsies the musical before that, but the show just blew me away. And the live production reminded me of why I fell in love with the show in the first place.

I love Newsies, too! It’s one of my new favorite musicals (discovered it this year; don’t ask, long story).

Me too. I saw Newsies on Broadway 10 years ago – I was only in NYC briefly, it was a Monday night and not much was on apart from this new musical I’d never heard of before. Decided to take a chance on it and I’ve been raving about it ever since! But I was nervous about seeing this production as I didn’t want it to spoil my memories of the Broadway show. But now you’ve really made me want to go see it, so thank you!

That there should be such acclaim for a musical “Hamilton” intrigues me…it is full of historical inaccuracies for in truth Hamilton was not an idealist committed to democratic principles.

An examination the history of the time shows Hamilton to be a self seeking reactionary with anti-democratic politics who used violence to crush dissent… he also proposed to have an elected president and elected senators who would serve for life, contingent upon “good behavior” and subject to removal for corruption or abuse.

Hamilton really wanted to take the idea of self government out of the Constitution, claiming that power should go to the “rich and well born” the class to which he saw himself attached…except that he was only rich, but not well born.

Further more it was Alexander Hamilton in 1790 said that as much capital as possible should be in the hands of the few rather than spread among the many..laying the foundation as I see it for Predator Capitalism.

Hamilton had suggested that the new Republic’s government should reimburse the securities it owed to those who fought in the Revolutionary War at their full price. When speculators heard of this, they bought the securities from the fighters in the Revolution at a fraction of their cost, hoping to make a good profit.

There was much opposition to this, many in the newly established Congress wanting a fairer reimbursement for those who had actually done the fighting. Much wheeling and dealing carried on in this and other matters which were to have long term consequences for the new Republic.

Two of the most important were to do with slave holding and the siting of the capital of the Republic in a swamp on the banks of the Potomac, rather than in Philadelphia, which was where both of the Continental Congresses had met, as it was a centre also of anti slavery sentiment.

So the many people and their families who fought, died and suffered for the Revolution were short changed for the benefit of the rich few.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose!

“laying the foundation as I see it for Predator Capitalism.”

All capitalism is predatory capitalism.

An economic system where the means of production are privately owned by the few, operated anti-democratically, and deriving profit by not paying workers the full value of their labour, is inherently predatory and exploitative. The only difference is in scale.

It’s a very American thing where it portrays them as the heroes and hides a lot of their atrocities. It pokes fun at itself a little, my favourite line is from Burr saying the constitutions a mess… it really is and has caused so many problems, US should be an example to the world of why constitutions are awful. a document written more then 2 centuries before the first computer governs all laws and foundations for society and the idea of changing it is considered abhorent… cause that makes loads of sense….

All that said the musical is utterly amazing, i saw it in west end 3 days before it shut, had had it planned for months so glad we got to go, it was easily the highlight of my year, outstanding performances.

May I just say, thank you for your dedication to historical accuracy? I still love the musical, and I’m not sure what its historical inaccuracies say about us as a society since it still has a lot of artistic merit (as opposed to say, Disney’s Pocahontas, which IMHO does not). But, again, thank you.

Dear sir, you seem to completely miss that Hamilton is theatre; the show makes no pretense of being a documentary.

Thankfully, musical audiences have room for all types.

Actually a lot of these issues and hypocricies are covered in the musical. I had the absolute pleasure of seeing it on Broadway and was blown away. It is very layered and surprisingly turns discussions about the foundation of the Treasury into song and dance numbers. It was also developed based on a renowned biography of Hamilton and in conjuction with the historian who wrote it.

When I saw Hamilton in the West End I felt as if I had been blown onto the back wall of the theatre with a water cannon – such was the impact of the energy coming off the stage.!! Quite extraordinary and groundbreaking! yes rap, with Shakesperian level lyrics, full orchestra music, tight tight choreography and rich detailed costumes. Stunning!!

I love Hamilton, but they’re not Shakespearean level lyrics.

We could argue for days over whether the lyrics are Shakespearean level, but I’m just gonna come out and say: I’ve always wanted to be a lyricist and I don’t have the talent. Therefore, I have mad respect for those who do, esp. on Lin-Manuel Miranda’s level. And Hamilton as a whole is…well, you know what I think, you read the article.

Went to see the stage show in the West End Just before lockdown. Unfortunately the Metaphorical herd of elephants on stage rather spoiled its superficial cleverness.

Seen it twice in London for two successive birthdays, After the first show I made an mp3 disc of the soundtrack for the car -it hasn’t been out of the cd player since.

Interesting article! I didn’t really make a connection between the 3 until reading this article, but the New York City setting feel very important to all three shows!

Very enjoyable read! I hadn’t really thought about the shared setting, the city, before reading this. But as I think about, I do tend to associate each of these with New York. Would love to someday see any of these in the city.

Me, too. My dream is to see a Broadway show in NYC one day. Unfortunately, COVID-19 protocols still make that prohibitive (my disability has a visual component that means I cannot wear masks and move safely, even with support, so until protocol is completely lifted, I won’t be traveling there. Unless it has been already? I haven’t kept up like I should).

I loved everything about Hamilton when I saw it on stage in London and will really try and see it on screen if I can. The only thing that jarred with me were the chorus women’s costumes but maybe that’s just me. I also loved that line about ‘get the job done’ and it produced a reaction in the theatre when I saw it. Anyway, I recommend it and I usually really hate musicals.

I’ll be honest I’ve heard a great deal about it but I really cannot stand musicals. I made a concerted effort with Moulin Rouge but had to give up 15 or so minutes in. I wonder if there is there any hope for me watching this?!?!

There really is. Took my wife to see it in the west end as a birthday present and thought it was amazing.

After “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” I can’t stop thinking that Lin-Manuel Miranda is actually as obnoxious as he portrayed himself.

Curb and Extras have certainly opened my eyes about many British and American celebrities.

The funniest moment in the brilliant I May Destroy You…”They’re going to play Hamilton the musical”

History repeating itself. Who says we have nothing to learn from history?

About time to remind us what it took to have a modicum of rights for the working people. We are most oblivious to the fact that it was not so long ago when striking workers took a great risk of getting killed.

Ditto for union organisers who tended to have short lives. They were beaten, mutilated, murdered and disappeared right up to WWII.

The employers have strong organisations and they have high solidarity (“black lists” of union members were circulated in Britain until the 1980s at least). Why shouldn’t workers be organised? Mind you, I’ve been running a small business with a couple of people working with me not for me, and for us what was good for one was good for all because we needed each other.

Anyway, no advancement of rights or benefits for workers in general have never been given without a fight, and for most of history those fights were bloody. Only when a straightforward right to strike was decreed by governments did the blood stop flowing for the most part (remember Thatcher’s head crackers in the miners’ strike of 84-85).

Aaaaaand, cue the mic drop.

Annie was an annoying musical in the best of times.

Newsies musical is based on real events of child-labour exploitation. It’s becoming more and more relevant today as more and more workers are being exploited and left without a real living wage.

Agreed, so much. Now, as you know, I do have mixed feelings about the fact that they sanitized it due to the medium, but I also think they didn’t sacrifice the gravitas as much as they could’ve (Crutchie and Letter from the Refuge, looking at you–PUT THE SOLO BACK ON THE SOUNDTRACK, YOU FREAKING COWARDS)!

Ahem.

But yeah. That’s part of why I wanted to write this piece in the first place. These are American stories, and with the possible exception of Hamilton, they don’t get the attention they’re worthy of, because people think, “Musicals, how cute.”

I’m old enough to remember singing the Strawbs ,Part of The Union song, with gusto, it’s still relevant today if people are smart enough to understand how their rights are being eroded.

Me too. Fantastic anthem!!

I saw the Newsies show on the opening preview night and the audience reaction was insane. My experience that night was astounding. I didn’t know what to expect from this production of the show but I have come away in absolute awe. I have never had such a strong reaction to a show in the way I have to Newsies. I haven’t stopped gushing for a week and a half. I’m looking forward to revisits because I know I’ll be able to spot things I missed last time with how much is going on. I want to be able to appreciate every little aspect.

I understand. I discovered Newsies (the musical, not the 1992 film, I hate the film on principle) this past summer, during a fairly rough spot in my own life. And I was, am still, blown away. I’m a writer, so I’m really into the characters and themes. Even beyond that, the themes of these boys learning to stick by each other, developing deep friendships, embracing courage on levels they thought they couldn’t, maturing out of escapism…excuse me, or I’m going to start gushing.

I was there too, i still think about that double standing ovation for seize the day.

I’m delighted about “Hamilton”‘s success because it’s always wonderful when an original American musical makes it on Broadway. But my WORD I’m tired of rap. This is not a new art form, folks. For pity’s sake, “Rapper’s Delight” came out in 1979! When I saw the first promo featuring Miranda performing “My Shot” my heart sank. It sank lower when I found out James McAvoy’s “Cyrano” turned de Bergerac into a rapper too. The hell with it.

Yeah, and while we’re at it, when will pop culture get over rock and roll? And jazz? And opera?

Rap/hip-hop isn’t to everyone’s taste, but it’s not going anywhere, so if you don’t like it, maybe just listen to something else.

And while it’s obviously not a new art form, it is new to the rather conservative world of Broadway. How many other successful rap musicals have there been?

Luckily, you are wrong. Hamilton is a work of genius.

Annie the musical, despite being full of punkky brewsters, is a pretty dark tale. I wish the consistent remakes weren’t always frothy and sickly sweet. It could be edgy, brittle, ominous. Kids in care, poverty, stern housekeepers – the whole thing could be recaptured in a contemporary setting, and do well from it. Keeping the songs and dance, it could actually be a really good musical to do creative shit with.

That…is a legit inspiring comment. What I mean is, I think people discount Annie because it leans too much on the extremes. For instance, yes, Miss Hannigan’s is not a good environment for any kid and we can stick with that. But, like, in this day and age, she’d never get away with starving kids and locking them in closets. She’d have to be sneakier–so let her be sneakier.

On to Warbucks–does he have to be a billionaire? Like, what’s wrong with Annie just being adopted by a regular old couple who maybe can’t have kids? Maybe already have bio kids and chose to adopt because they are honestly good-hearted people? Why does Annie have to have the trappings of a rich kid to be happy? It would be enough for me, coming out of that environment, to hear, “You know what, kid? You deserve a safe, warm place at night. You deserve bubble baths, and toys, and books, and food you actually like, on the regular. You deserve to play. If there are chores, they’re done because you’re part of the family, part of the team. And if you mess up, you’re disciplined, not punished. Discipline is to teach. And you’re never kicked out or locked away.”

As for Annie wanting to find her real folks–sure, I can go with that. We could even keep the kidnapping plot because hey, people can be sickos, they do that kind of crap. But like, I would want Annie to have some solid clues. Maybe she *knows* her parents are David and Margaret Bennett. Maybe she wants to find them and is also like, “I love my adoptive folks, too; I’m in this for closure, not to say one set is better than the other.” Because the way Annie is written, it comes off like she’s given everything, but still isn’t satisfied. Which is…okay, but weird?

Agreed. I saw the musical and agree that it is old fashioned, but it has been sweetened too much – there’s never any real threat.

Newsies is politically relevant to some; just a Disney musical to others. But I loved it.

Newsies is my absolute favourite musical, and I got to see the show during previews (with my best friend who I met because of the show!), it’s like nothing I’ve ever seen – all my expectations were completely blown away, still can’t get over the choreography. We met Michael, Bronté, Ryan & Matthew at stage door and they were so lovely! Genuinely the best thing I’ve ever seen, I’d go and see Newsies 1000 if I was able, could watch those boys dance forever.

Is it as good as les miserable?

That’s for you to decide. 😉

Rapping about the federalist papers. Not easy to pull off. And there is a lot of that historical detail in the songs. It’s not simplified at all. I came out feeling that I’d seem something important especially with the non white-cast flipping everything over to look at itself. Art doing a powerful thing. I’m desparing now after that optimism. Maybe it raised a question an unanswered question.