Illuminated Landscapes: The City in Blade Runner and Lost in Translation

The French philosopher Gaston Blanchard wrote “Tout tremble quand la lumière tremble” – “Everything trembles when the light trembles” suggesting an intermingling between the presumed passivity of light and the role of an actor it seems to implicate. It is not only the fragility that the manufactured, anthropogenic light inhabits, but also implies that everything around it and touched by it is in a permanent connection and in a continued dependence of it. While there is a fundamental element to light that accompanies all life, and appears to be an essential scientific and philosophical presence in the world, it also seems, as literary scholar Bill Brown points out, that “the backstory is missing in the history of light – it ought to begin with a godly explanation of the sort ‘Let there be light!’” implying more than the inanimate object suggests. Approaching light as an inanimate object, contrary to the natural occurrence of light and its integral connection to life, then suggests that technical man-made light is part of a society and has taken on a life of its own.

The modern city in the 20th and 21st century provides a perfect embodiment of light outlining a network and having its own agenda, especially the flashing and flickering neon lights illuminating the urban space. Although the neon lights of today are mostly not filled with the gas neon, but with other types that fulfill the same purpose, they appear to merge under one term as “neon.” The multimedia artist Rudi Stern details this in his work Let There Be Neon (1979) where he describes the transient existence of the classical neon signs. Neon lights hold a short lived life from their beginning at the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893 to their mainstream arrival in the 1930s, followed by their demise given the availability of cheaper synthetic materials. The connection to the urban landscape suggests that the association with the word “neon” commonly stands in relation with the lights of the city, the neon signs and not only the old-fashioned and hand-crafted fluorescent tubes filled with the gas neon.

It is the incorporation of neon lights into the landscape of the city, that as Stern suggests “has given the city its visual identity,” such as Las Vegas, New York, and Tokyo. Stern dedicates entire chapters to the visual landscapes of the Las Vegas Boulevard and New York’s Times Square. He points out that neon was “one of the available local building materials, and neon has been a vital element in its freewheeling, exuberant architecture” in Las Vegas, while the Times Square “before television … was America’s national billboard and piazza.” The city landscape embraced itself as a monumental advertising board, in which it furthermore became the imagination of a futuristic condition, or as the French philosopher Bruce Bégout puts it a “Zeropolis.” This city of the void created the impression that there is an emptiness behind the flashing neon lights, which might only be filled by giving into the fiction constructed by the city.

The effect of neon light as seen in popular film productions from the 1980s, most notably in the Warner Brothers production Blade Runner (1982), and Walt Disney’s TRON (1982), highlight the significance of neon lights and their effect on the culture of the 20th century. Both movies emphasize not only the coming of new technologies, foreshadowed in the artificial intelligence in Blade Runner, but also the impact of the then relatively new computer game culture and the accompanying factor of total emersion into the digital world in TRON. More contemporary productions like Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation (2003) and Spike Jonze’s Her (2013), have less of a science fiction component but emphasize the lostness in a seemingly surreal and inhuman environment amid the flashing setting of neon signs. This rather artificial and inanimate space of fluorescent neon lights suggests not only that the lights themselves have agency in that they perform for the society around them, but they also enable something for the social beings that act in their habitat.

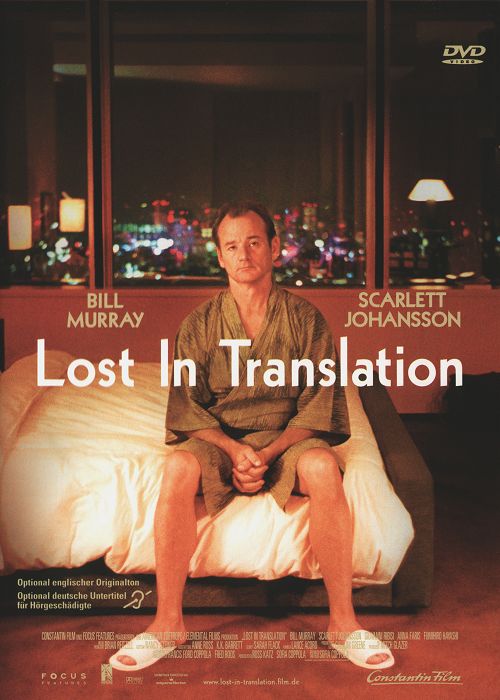

Comparing the use of neon signs in Lost in Translation with Blade Runner reveals a somewhat resembling portrayal of the city as one omnipresent billboard that seems to be inescapable for the society in its surroundings. This new ‘cinematography’ and its flashing lights, implied a illuminating supremacy that enabled the urban space to be viewed in its own fiction rather than reality. While Blade Runner plays with the ideas of the hostile urban space, dominated by large advertising and genetic creations, it also portrays the opposite of the anarchic turmoil of the city, and portrays its possibilities. The cultural scholar Christoph Ribbat describes this as a “delirious chaos,” which can also be seen in Lost in Translation, where the protagonists Bob Harris (Bill Murray) and Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) struggle with their loneliness but eventually find meaning in the flashing jungle of Tokyo’s neon signs, which seemingly act as an enabler for their transformation.

In Lost in Translation the protagonists Bob and Charlotte are seen living out their lives mostly in front of the city lights, which appears to orchestrate the neon lights as some kind of passive third protagonist. Reviewing the film in 2003 movie critic Maria San Filippo presents the city itself, mostly brought to life through its lights, as an actor that portrays the romance between the characters. She considers “Lost in Translation’s third significant character … Tokyo itself” made visible through its lights. In a scene where Charlotte sits on the windowsill of her hotel room gazing faraway into the neon signs of Tokyo below her the camera changes its main focus from the lights on Charlotte, suggestively changing the main actor from object to human. In another scene Charlotte is riding a taxi back to the hotel, while looking out of the window, seemingly merging with the fluorescent billboard signs mirrored on the glass. Her interplay with the neon signs suggests that she has become part of the network of neon lights, while simultaneously embracing the object of light as an actor. The constant intermingling of actress and object creates its own visual cinematography, revealing a relationship between the material object and the social. Charlotte’s affinity to Tokyo’s neon signs implies a similarity to Bachelard’s notion of the intermingling between active and passive light, as well as being embraced by the human protagonist.

Likewise close up of signs in Lost in Translation, the focus on neon lights in Blade Runner gives room for the art of the fluorescent tube itself, revealing it to be an artful installation. The neon illuminations used in Ridley Scott’s classic movie appear to be an homage to the old-fashioned, hand-crafted fluorescent lights of the 1930’s. Scott used neon lights for his vision of the futuristic, yet brutal city of the future. The various shots that center on the neon signs, and the flickering city lights, give not only room for the lights to be an actor, but also give room to focus on the art of the neon sign itself. The incorporation of close ups and emphasis on actual neon art stresses the movies ability to create art likewise the artists Dan Flavin’s neon installations. The neon art displayed in Lost in Translation and Blade Runner is dependent on systems that assure a rather rationally urbanized and industrialized space, as well as fictionally romanticized landscape to be fully incorporated into the act of the movies. Especially the contrast of the humans versus the object suggests that there is more to the neon sign, implying it to be what Stern calls a “living flame,” which reveals to appear highly expressive in moments of despair.

When Bob drives through the inner city of Tokyo seemingly depressive and lonely, the neon signs stand in an intense contrast to him. The neon tubes take on an agency of their own, exposing his emotional condition in an act of becoming the additional element in the story. It is the element of the “third (inhuman) character” as seen in Dan Flavin’s art, that enables light to have its own agency here. When the bioengineered replicant Roy Batty lives through his final moments next to Rick and in front of a neon sign, he surprisingly reveals an array of human emotions in a powerful dying monologue. Even though the two movie scenes are very different, they both allow the neon lights in the background to enable their full fictional potential.

Incorporating the background lights into the storyline, and making them an actor empowers them to achieve some sort of “visual identity,” as Stern puts it. Neon transcends the void of the “Zeropolis,” and enables new compositions narrated by the urban space itself. In cinematography this enables a whole new way of narrating, and furthermore allows for seemingly invisible and inanimate characters to take an agency of their own. To put it like Stern – Let there be Neon!

Further Readings

Brown, Bill. “Eine kleine Geschichte des Lichts (Dan Flavin / Gaston Bachelard). Materialität: Herausforderungen für die Sozial- und Kulturwissenschaften. München: Fink. 2015. Print. 1-13.

Ribbat, Christoph. Flackernde Moderne: Die Geschichte des Neonlichts. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2011. Print.

San Filippo, Maria. “Lost in Translation.” Cineaste Winter 2003: 26-28. Expanded Academic ASAP. Web. 21 May 2016.

Stern, Rudi. Let There Be Neon. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1979. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I’m one of the freaky fans who has seen Blade Runner a million times! It is absolutely hypnotic … the whole look of it just entrances me. Although I’m usually pretty up on the background and interesting facts of movies, for some reason I never really researched this one. Maybe I just wanted to experience the film and not know too much — however, I found this fascinating and am glad to get better acquainted with it.

You know, perhaps the lack of personal chemistry between Ford and Young is precisely what made their interaction in the movie so real — he has ambivalence about her anyway, she is nervous and vulnerable with him, and it works.

The rainy, smoky, crowded streets are portrayed so well that it has always made me feel claustrophic and very nervous to view them. That takes real talent to create. OK, I’m off to pull out my copy and view it once again (for the millionth and one time?)

One of the most far-reaching steps that Scott took was to hire Syd Mead as the “visual futurist” for Blade Runner.

tuska. I believe Mead was originally brought in by Scott only to design the vehicles and spinners, but when Scott saw how he had illustrated the backgrounds as well, to give the vehicle designs some continuity with their surroundings, Scott had Mead work on the overall look of the sets as well. A wise decision on Scott’s part, which worked out superbly. Oh and by the way, if you look very closely at the landscape of the Megapolis, you’ll spot an old model of the Millennium Falcon (on end) being used to represent a building. Ingenious!

I’m a bit of a geek when it comes to ‘Bladerunner’ and consider it to be one of the finest sci-fi films ever made. In my opinion it’s a masterpiece…that is ‘Bladerunner: The Final Cut’ and not the original 1982 theatrical release with that pointless addition of the end scene lifted from some of Kubricks’ left over stock footage from ‘The Shining’.

Watched Lost In Translation recently. Warning: I’m a LIT-hater, but I respect people who like it, so I’ll try to give my reasons.

The shots in this film hit me right away as somewhat predictable, like we see a postcard view and it looks like … a postcard. There’s a standard framing to things that strikes me as unoriginal.

I remember when watching the film that the architectural shots looked exactly like the architect planned; there was one shot of the glass hotel that bugged me, because I actually felt like the director just picked scenes out of a hotel brochure. They’re nice and she spent a lot of time finding picturesque things to point the camera at, but once the focus and exposure were correct I didn’t see much value added.

Similarly, things like neon signs at night and Buddhist temples are pretty hard to mess up.

Maybe that’s part of the narrative, that the characters are kind of trapped in a bunch of standard scenes.

Great to see this article go live. An ‘illuminating’ piece of work (excuse the deliberate pun) and a fine read.

Nothing lost in translation here. Sorry, Amyus started it.

Reading this article, it really made me think about the thought process behind crafting the mesmerising city of Blade Runner. It seems to be a level of thought and striking visuals that most modern Hollywood films can’t replicate (despite bigger budgets and advanced technologies). Fingers crossed for the sequel (from the director of Arrival, so there’s still hope).

What other films cover the whole neon Tokyo/nightlife? It seems like a backdrop we don’t see often.

Enter the Void comes to mind. Kind of a visceral trip though and not for everyone.

I am a cinematographer and I am very fond of these films and the way it is lit. I have studied the films carefully over several viewings.

“Lost In Translation” was the film that woke me up to the beauty that could be achieved in adopting a minimalist approach to cinematography.

This publication is truly magnificent.

$100,000 was spent on neon signs alone!

I’m a great fan of “Blade Runner,” and have watched it many times. It simply does not age or become outdated.

I knew little of its background until reading your piece. It’s so interesting that I became completely absorbed reading it again.

I find Lost In Translation to have a Japanese style (i.e. the photography of Takashi Homma and Rinko Kawauchi, or the artwork found in the films of Hayao Miyazaki or Katsuhiro Otomo, or the visual cadence of arthouse-animes like FLCL and Cowboy Bebop) mixed with an Italian style (i.e. the cinematography of Michelangelo Antonioni’s films). Sofia Coppola’s movies are stunningly gorgeous.

The visual aesthetics of the Ridley Scott films are timeless. Every scene in Blade Runner is of a piece, its world is total in itself.

Last night I watched “Alphaville” a Jean Luc Godard´s film from 1964 that had all that we love in Blade Runner but in Black And White… don´t misunderstand me I love Blade Runner but Alphaville is like an inception for the Scott´s masterpiece.

Lost In Translation is definitely one of my favorite movies. Really great acting, charismatic characters really brought out by beautiful casting, the shots, the music, the sounds and locations, it’s really just beautifully crafted together. Lots of people seemed to miss the point of the movie and what made it good, but yeah…they have Transformers 7 I guess.

Lost In Translation is my favorite movie of all time. I have only seen it twice because I don’t want it to be overplayed. my fa-vo-rite movie

Great focus on the cinematographic merits of the films.

This article makes me want to rewatch both movies just to observe the cinematography. Thank you!

I got to see Lost In Translation at the theater during a Bill Murray week which was a treat since I hadn’t seen it on the big screen.

Thanks so much for covering these stunning movies.

It might have been interesting to see what Lost In Translation and BladeRunner would have been if seen through the eye of a digital video camera, I’m not sure that it would have had quite the same impact.

I find Lost In Translation to be one of the most rewatchable movies. I think films that don’t rely too heavily on plot and manage to create the right characters and mood can be seen over and over again much more so than films that rely heavily on plot and twists.

You make a good point. I think those types of films stay with us much longer for that reason. They make a greater impression on our minds with just the right mixture of character and mood. For some inexplicable reason, there are certain films where I feel satisfied having watched them only once . . . whereas there are others I never get tired of watching over and over again. Both of those categories can contain perfectly good films so it isn’t necessarily an issue of quality. I guess it’s partly because films that rely too heavily on the plot are often more disposable. Exciting new plot twists can be a dime a dozen sometimes. You have to invest in more than just plot for it to really be memorable. Once you figure out the sequence of events and are given “the big reveal,” the mystery is gone and so is the potential for viewers to rewatch.

Jordan Cronenweth and Ridley Scott are gods.

The look of Blade Runner can tell the story in itself, a contradiction of fascinating imagery within a world of decay, the gloomy vision of baroque futurism.

Two beautiful classics.

It is interesting to think that something so or not so obscure could have a deeper meaning than one realizes.

The visual styles in these are gorgeous.

L.J.’s exploration of neon’s crucial role in fully developing the characters of Deckard, Batty, Bob, and Charlotte is most informative and perceptive. The moods evoked by glaring, subdued, flashing, and flickering neons have added greatly to cinematography’s visual lexicon. Neon’s cold light gives each color an unearthly glow. Vaportube pawn shop and payday loan signs suggest desperation and poverty. Dive bars lined with neon beer signs bathe drinkers in a seductive, albeit unseemly ambiance. Flickering motel vacancy signs signal short-term, illicit trysts. As L.J. has posited, neon can be a formidable onscreen enhancement.

I believe there is another effect of such overpowering illumination when combined with a chaotic environment, be it the layer-upon-layer stacking of a future city’s clash of cultures, or a modern overloading of a city’s entertainment and tourist sector.

Having seen four versions of Blade Runner and multiple viewings of Lost in Translation, I am at once taken by the notion of impending change in both stories. Both share dazzling-to-the-point-of-chaotic lighting elements, teeming populations, and the search for human emotion or lack of it. Aside from being hypnotic in their own right, the profusion of lights and signs present a soul-stirring chaos – suggesting the Jungian premise that Change is precipitated by, and optimally an adaptation to, Chaos – whether accidental or deliberately fabricated for or by the protagonists. The desired goal is to straddle Order and Chaos through Change.

So we examine a Paid Gunner and people Lost in Transition.

At the outset, Deckard, Harris, and Charlotte are clearly in stasis, i.e., overwhelming order – Deckard is settled into his alcoholic retirement after assassinating errant replicants, Harris is enduring an unfortunate career hiatus with drink and low-status ad work, and philosophy graduate, Charlotte, is emotionally numbed by her relegation to being merely a tag-along spouse.

This unrewarding stability, wherein life’s excitements and disappointments have equal yet opposing weight, inevitably produces boredom and dissatisfaction. Reluctantly, they each embrace chaos. Deckard returns to hunting violent replicants; Bob and Charlotte betray their spouses and form a spiritual bond. The characters strive to understand who they can be since they are no longer satisfied to be what they had become.

“They don’t advertise for killers in the newspaper. That was my profession. Ex-cop. Ex-blade runner. Ex-killer.” – Rick Deckard

“I just don’t know what I’m supposed to be.” – Charlotte

“You’ll figure that out. The more you know who you are, and what you want, the less you let things upset you.” – Bob Harris

All three situations are recognizable to audiences as extreme variants of mid-life crisis/early retirement/marriage-gone-cold re-assessment of one’s desires, goals, and capabilities.

Blade Runner’s gritty, retrofitted Los Angeles and Tokyo’s kitschy, Vegas-on-amphetamines, optical overkill – e.g., Shinjuku-Kabukicho and Shibuya – are intoxicating, experience cauldrons where one struggles to maintain cultural and conceptual equilibrium. Deckard’s crowded streets, biotech-savvy Egyptian and Asian shopkeepers, and preternatural, exotic “reptile dancer” are dystopian extensions of Bob and Charlotte’s embrace amidst a bustling street crowd to share a final, intimate moment, their mad chase through the color-splashed Pachinko Palace, and sensual nightclub socializing under huge, fluorescing, jellyfish-like globes.

“In all chaos, there is a cosmos, in all disorder a secret order.” – Carl Jung

The establishing urban landscape shots in Blade Runner are highlighted by huge, flashing plumes of roiling burn-off gas stacks atop skyscrapers (possibly the discharge human-produced methane from urban sewage?) allude to an eruption of underground, volcanic forces; geothermal spewing that portends destruction – an upheaval is coming and it involves a man who may be a replicant hunter, unaware that he is programmed to destroy his own kind. Perhaps these rooftop flames prefigure a phoenix… or pyre.

Deckard searches for non-human androids becoming aware of their short, pre-destined lifespans, while detached Harris searches for his fully-human self – lost in his stalled career and perfunctory marriage. Charlotte longs for the attention and recognition she deserves as an educated, sensual woman. Bob and Charlotte find in each other kinship, as Deckard does when he is saved by a dying Roy Batty. As L.J. notes, the lighting in both films serves as needed atmospheric backdrops as Chaos/Change apotheosis takes place – as well as a visual inducement for the audience to vicariously participate in these self-realizations.

“You’re probably just having a mid-life crisis. Did you buy a Porsche yet?” – Charlotte

We seek change without effort until the desire to effect the change finally requires our embrace of that will cause disorder and, optimally, the re-imposition of new, situation-appropriate order. That is how we navigate change, and our environments – both natural and man-made – to stimulate re-invention.

Bathed in chaos – optical, intellectual, and emotional – all three are changed, and the lesson-learned is that life can only be fulfilling in the present. The past is a scatter of posed photos and lonely marriage beds. The future, for those who wish to shape it, is a continual progression of choices to meet chaos and its power to produce change.

MJH

There are some other things that LiT and BR share. For example in BR Deckard eats at an Asian food bar and when he picks up his chopsticks he simulates sharpening a knife by rubbing them together. Bill Murray’s character does the same thing in LiT. In BR there is a chase scene where Deckard is shooting at a replicant as they run through a glass shopping arcade. In LiT Murray and Johanssen are chased through a glass shopping arcade with a bartender shooting at them.

Great article. The neon lights of the city play very well into the themes of artificiality vs authenticity in Blade Runner. The synthetic lights replace the sun just like the replicants replace people. Both replicants and neon lights are unnatural and man-made, but they still feel alive in many ways. This feeds into a central question of the film-are artificial humans still humans?