Are Immersive Exhibitions Ruining Art?

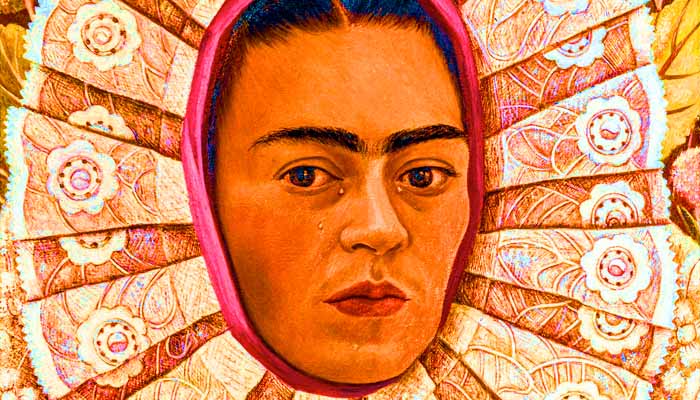

Vincent van Gogh. Pablo Picasso. Claude Monet. Gustav Klimt. Frida Kahlo. These names, for most people, represent titans of the fine art world, artists who in their lifetimes produced art so significant that its echoes have been felt across generations. Their works and lives have been romanticized, parodied, chewed up and spit out again in the form of merchandise and media. The longevity of their names is a testament to how their works – many of which were created in dark times, without realistic expectation of recognition or fame – have touched the hearts, minds, and imaginations of countless people throughout generations. Yet, these artists now have something new in common. Their works are all the subject of a new form of entertainment sweeping across the Western art world: immersive art exhibitions.

Immersive art exhibitions draw in audiences by using modern technology – mainly projections and soundscapes, though sometimes more ambitious elements like virtual or augmented reality – to add new dimensions to familiar artworks. In most cases the audience stands or sits on the floor in a large, empty room as a work or series of works from an artist is projected on the walls, floor, and ceiling around them, literally integrating them into the artwork. Stars flicker in the sky, brush strokes of water flow gracefully, the arms of a previously static mill turn slowly in an imagined wind. It’s like stepping into the world an artist imagined – and one they themselves never got to see.

Over the past few years, the popularity of these immersive art experiences has skyrocketed. Some of the more popular include “Immersive Klimt Revolution,” “Beyond Monet,” “Immersive Frida Kahlo,” and “Imagine Picasso,” plus five separate van Gogh immersive experiences, each licensed by a different private company 1. The popularity of these exhibits is evident, and they are lauded for introducing a new generation to fine art. Supporters of the new experiences hope that visitors will be drawn in by the spectacle and promise of snappy social media photos, and will become engaged with the artists, seeking out more information once the event ends.

Yet, like any new technology, these exhibits have many vocal critics. They are criticized for cheapening the work of the artists by de-contextualizing their pieces and stripping them of their educational value 2. The loudest criticisms come from people who believe that the immersive elements place the focus on the visitors rather than the artists. This superficial engagement with the art – only attending an exhibit to get something out of it, presumably social media clout – is bemoaned as an expression of a vain and self-centred generation.

But immersive art is not new, and neither is the pervasive feeling that society is becoming increasingly self-obsessed. Compared to other immersive experiences that offer more intense engagement for all five senses, sitting in a room with a projector seems fairly mundane. So, what is it that draws people into these new immersive art exhibits? To answer this, we have to turn to the past, to the rise of this cultural vanity, and to the work of one of America’s most influential cultural critics.

The Culture of Narcissism

In 1979, cultural historian Christopher Lasch published The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in An Age of Diminishing Expectations. The book made a splash in the United States, winning the 1980 National Book Award for the “Current Interest – Paperback” category 3 and continues to be widely read and discussed to this day. The book is fairly dense, and occasionally diverges into tangents on social issues that have not held up in their relevance, but the overall argument on the shifting values of postwar America, namely towards a growing obsession with the self, remains relevant today.

Lasch’s definition of narcissism varies slightly from the popular understanding of the term as an unhealthy vanity. He denies that its core quality is selfishness, arguing that the obsession with the self is in fact, paradoxically, a product of losing a sense of selfhood (xxxiii) 4. Americans were increasingly turning inward to try and rediscover the connection to themselves and to their communities that was lost among the carnage of the first half of the 20th century. What is notable about narcissism for Lasch is what people do to express this new vanity. Throughout the book, he highlights two main products of narcissism that impact how people interact with culture and one another: a rising need to use others as a mirror, and a devaluation of both past and future. Both of these products can be seen reflected in the new mania for immersive art exhibitions.

Me, Myself, and I

Lasch’s first point will be unsurprising to those familiar with the popular understanding of narcissism. It aligns with the original Greek myth of Narcissus, in which a handsome young man drowns or wastes away (depending on the version of the myth) staring at his own reflection in a pond 5. It’s widely accepted that narcissists and mirrors go naturally together. But how can people use one another as mirrors?

Lasch writes that, more than selfishness, narcissism is a weakness of character, through which people are increasingly unable to find meaning within themselves, and are forced seek it from exterior sources (xxxii). Self-affirmation requires a sense of selfhood at one’s core, not one “subject to environmental determination” (xxxiii). Essentially, people are no longer able to find meaning in life through their relationship with themselves. They require external validation. In this way, Lasch’s narcissist is trying to find meaning in life not from within, but from without, not gazing at themselves in a mirror but gazing at themselves through validation from others.

One notable element changing the environment in America was the prevalence of new recording technology in the 1970s. Lasch argues that cameras and video recorders were leading everyone to behave as if they are being watched at all times (61). This has only become more accurate as cell phones with high quality cameras have become pervasive over the past few decades. This acute awareness of being observed leads people to feel as if they need to perform. Consider, for example, how desperately people look to media or celebrities to determine the next hot style, or change their language around trendy slang. More recently, people have started switching up their wardrobes to fit new manufactured aesthetics such as the recent popularity of cottagecore, dark and light academia, or the e-girls and boys popularized by TikTok. These internet “personalities” allow people to place themselves into defined boxes, making them easily understandable to others and thus understandable to themselves. Yet as trends come and go, the narcissist needs to search for new reflections, to try and discover a fresh connection to their “self.”

If the narcissist is constantly searching for a way to see themselves in the things around them, few things could satisfy their hunger more than an immersive art exhibition. They are in a room with strangers yet fundamentally isolated, particularly with the social distancing measures due to the popularization of these exhibits over the COVID-19 pandemic. Surrounded by massive projections on every surface, the narcissist literally becomes part of the artwork. An exhibition cannot be immersive without intimately involving the subject viewing the work, meaning that it could not function without the narcissist being present. Indeed, if the narcissist was not so skilled at seeing pieces of themselves reflected in those around them, the immersion of the exhibit would perhaps not be as appealing or successful.

This integration into the actual artwork, combined with the social media opportunities encouraged throughout the exhibit, allows for constant observation by those both physically present and not. This makes immersive art exhibitions ideal to satisfy – albeit temporarily – the needs of Lasch’s narcissist.

Critics argue that this self-absorption leads to the immense popularity and profitability of these exhibits, which pressures traditional exhibition spaces to attempt to accommodate the trend. The rise of digital technology has lead museums and art galleries to rely to increasing degrees on interactivity and “nonconfrontational environments” that draw in visitors with promises of comfortable and engaging exhibits 6. By prioritizing sensory engagement and staying well within visitor comfort zones, the visitor always leaves the exhibit having gotten exactly what they want from it. They find no challenge to their preconceived notion of what the art is, or what it may mean. In this way, immersive art exhibitions not only accommodate narcissism within their own walls, but encourage the accommodation of narcissism in traditional art institutions as well.

Living in the Moment

Lasch’s second manifestation of narcissism is a disconnection from both historical past and the future. He argues that an inward focus leads to a desire for quick, temporary satisfactions, or a desire to live perpetually in the moment to the fullest extent possible (12). But where does this perspective come from, and what does it mean?

Lasch writes that postwar America found itself in a crisis of capitalism, or a sudden crisis of confidence in the functioning of capitalist society (1). The Cold War and the war in Vietnam lead to an impending sense of doom hanging over the nation, leading to a general loss of hope for the future (14). Pop culture and the collective imagination of the nation became preoccupied with a “sense of ending,” or a growing confidence that terrible things were guaranteed to come in the future (11). This shared feeling of impending doom lead to a shift in how American society collectively thought about time. If society has no future, what else is there to do but live for the moment? This newfound search for temporary and present satisfaction in turn leads to a neglect for the future generations, and a disconnection from the past.

Immersive art exhibitions, by nature, can only exist in the present. They take a static piece of art and turn it into performance art, something that must be experienced uniquely by the audience sitting in the room at its exact moment of existence. One it ends, that particular instance of it is over forever. The same person may return to watch the same show, but their experience of it, what they take note of and how they feel about it, will be different.

A significant criticism of these experiences is that these projections are decontextualized from the history of the artists and their works. The subjects of the paintings, the techniques used, and even the materials were all products of each artist’s contemporary circumstances. Modernizing their art into moving spectacles detaches it from its meaning outside of existing as a popular cultural object. Is the exhibition successful because people appreciate van Gogh’s art, or simply because people recognize it? Completely detached from any way the artist may have wished for their art to be presented, the immersive experience exists only for the gratification of those modern viewers who are in the room at its moment of presentation.

More than detachment from the past, immersive art exhibitions are artworks that have no preservation for the future. The artists whose works form the content of these experiences are so significant because of how their artworks have been admired for generations. A projection show is incapable of remaining static for future generations in the same way. Mostly held in “transitional commercial spaces” like warehouses 7, these exhibitions exist for present gratification, and then pack up and move on. In some ways this adds to the allure of the exhibition – see it now, or never again! With a new sense of pervading doom pushed on by pandemics, climate change, and fraught global politics, there is an understandable detachment from the future today that echoes that of postwar America. It certainly suits the narcissist’s desire to live in the moment.

Critics argue that these sensational and interactive exhibitions imply that traditional art is somehow deficient in its smaller, less dynamic form 8. Bombarding viewers with brushstrokes as tall as houses, they are deprived of the immersion that comes from staring at a static painting and engaging with imagination. Adding a more sensational form of participation prevents viewers from engaging in a subtler, perhaps more rewarding form of immersion forged between individual viewers and static art.

Is it Good Art… Or Good for Us?

So, if immersive art exhibitions are emblematic of what Lasch sees as problematic about narcissism in society, does that mean they are inherently bad?

Immersive art exhibitions certainly have many critics. They believe that the experiences undermine traditional art by being too sensational, de-contextualizing it from its past and future, and discouraging viewers from seeking the educational value of art. Yet by gatekeeping engagement with fine art, enjoyment is limited to the privileged few who live in or are able to travel to the expensive museums where the physical works are housed. Pop art has always existed as a means of circumventing institutions to reach the audience directly 9, and immersive art exhibitions – though themselves not cheap – offer fine art to a much wider and more diverse audience.

The second critique, that immersion cheapens artwork, similarly falls flat. Already, all good art requires some level of participation from the audience 10. Consider a good book, which draws upon the reader’s imagination to fill in the blanks left by the author. This engagement, albeit much subtler than the immersion provided by more sensational technology, forges a deep connection between creator and viewer.

There are merits to both sides of the immersive art argument. Yet, like most social issues, neither side is completely right. Immersion, like anything, should be consumed in moderation. A larger-than-life technological experience that leaves the viewer with some appealing Instagram photos certainly sounds like a fun afternoon. But it should by no means completely replace traditional and more educational art exhibitions. Art and technology will continue to grow together, and this innovation is important and should not be stifled. But being the centre of attention should not become a prerequisite for enjoying art. If it is, art loses the ability to challenge the viewer. And if all art is comfortable, how will we ever grow?

Works Cited

- Venable, Malcolm. “Immersive Art Experiences Are All the Rage — What Does That Mean for the Future of Art?” Shondaland.com, 25 October 2021, https://www.shondaland.com/inspire/a38039004/immersive-art-experiences-are-all-the-rage-what-does-that-mean-for-the-future-of-art/ ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “1980 Winners.” National Book Foundation, https://www.nationalbook.org/awards-prizes/national-book-awards-1980/?cat=autobiography-hardcover&sub-cat=current-interest-pb ↩

- All quotes and paraphrases are from Lasch, Christopher. The Culture of Narcissism : American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations. Norton & Company, 2018. ↩

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Narcissus”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 31 May. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Narcissus-Greek-mythology ↩

- Wiener, Anna. “The Rise of ‘Immersive’ Art.” The New Yorker, 10 February 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/letter-from-silicon-valley/the-rise-and-rise-of-immersive-art ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Taylor, Kate. “Immersive shows like the van Gogh and Monet exhibits betray art’s stillness.” The Globe and Mail, 13 August 2021, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/art-and-architecture/article-the-new-mania-for-immersive-shows-betray-arts-stillness/ ↩

- Wiener, Anna. “The Rise of ‘Immersive’ Art.” The New Yorker, 10 February 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/letter-from-silicon-valley/the-rise-and-rise-of-immersive-art ↩

- Venable, Malcolm. “Immersive Art Experiences Are All the Rage — What Does That Mean for the Future of Art?” Shondaland.com, 25 October 2021, https://www.shondaland.com/inspire/a38039004/immersive-art-experiences-are-all-the-rage-what-does-that-mean-for-the-future-of-art/ ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

You can make art from anything, on any scale, out of whatever materials you like. It can be a something smaller than a netsuke, or it can be the size of a mountain. You can make it on your own or orchestrate it with hundreds of other people. All of this has been accepted since the 1970’s. The difficulty is in making something good. This is just as true now as in the past. A paint brush is a technological device just as much as a holographic projection. Neither have any intrinsic merit. It’s all about how they’re used.

All true. But this way of presenting the art, quite different to the intention of the artist, assumes people can’t simply enjoy things for what they are.

If an art work is designed with the purpose of being immersive, fine. But efforts to make established art into an immersive experience is a bad idea. I saw an immersive van Gough exhibition in Berlin and it was honestly the tackiest exhibition I’ve ever seen. Also it looked like a lot of it was designed on windows 95 as a school project.

Saw the same thing in Melbourne. Horrible. Now … if someone enjoys that, fine for them. But I thought it was awful. I just want to see the paintings. It was awful in the same way that those ‘4D’ cinemas where the chairs move are awful. What I don’t like about it more broadly is that it’s sold as ‘bringing more people to art’ when really it’s a continuation of the dumbing down of everything, an assumption that the average Joe can’t simply look at a picture and be amazed. His attention span is so pathetic he needs to be tricked into the exhibition with a light show.

Why did I go… after all that rant? I dunno, it was post COVID lockdown and we were at the gallery and went in on a whim.

I saw a similar thing, but related to a Warhol exhibition piggybacking on a Picasso museum.

Sounds good to me. I hate stuffy museums where all you can do is shuffle round and look at things in cases or roped off, murmuring appreciation or derison as you go.

MoMA in New York was the biggest waste of my time out there. No touching the exhibits. No photos. Nowhere to rest. No food or drink allowed. No atmosphere. No joy.

There is no way you’ll engage me with anything like that. The best museums have chatty, knowledgeable guides, local interest exhibitions, hands-on experiences. I volunteer as part of the travelling crew for our local computer museum (hands on playable retro computing kit) so I do have skin in the this game, and I don’t think I’m alone in preferring something that engages visitors physically as well as mentally.

Touching something that may have a resale value of $Ms probably isn’t wise and as for taking photos in art galleries – whats the point? To prove that you’ve seen it as you stand in front doing a thumbs up?

I very, very rarely take selfies. I also have to be cajoled into being in other people’s photos because I don’t photograph well. I’m not comfortable in front of a camera. I take photos to document what I’ve seen and where I’ve been, not to immortalise my gurning mug.

I’m sure some of the computer kit we lug around to exhibitions is worth rather a lot of money these days, in rarity value if nothing else. That doesn’t stop us from allowing Uncle Tom Cobley and all to play games on it, stand their sticky fizzy drinks and hot coffee cups next to it or on it and eat greasy fast food near it or while playing it.

Just means we have to wipe up after them all and occasionally take interesting bits of kit apart to clean and restore it.

I’d still rather experience something than gaze at it adoringly. (Certain musicians are exempt from this attitude. I can gaze adoringly at them all day long.)

I work at an art museum where we have a lot of school groups visit. We’re quite firm on not touching the art, but when we give tours, we bring out samples of materials or scents/tactile things that are relevant to the artworks we’re looking at. In my experience, visitors love the multisensory connection, and it protects the art at the same time. I definitely see the value of having the immersive aspect but I also believe that there’s much more to be gained by having a personal, untimed experience with an artwork or anything else you’re seeing in a museum

Overpriced theme parks but y’know what… Who cares really, they’re better than the usual tourist traps. I’m old school myself but if it gets more people involved then bring it on.

I went to the London Van Gogh immersive exhibition , it was very underwhelming, apart from the VR bit, I felt very “un-immersed” in his art. The Van Gogh immersives elsewhere looked a lot better , maybe the venue was an issue.

It was ‘ok’ as an experience but felt like another arm of the Van Gogh industry that seems to take almost anything associated with him and try and create “a whole new immersive experience”

I saw the Van Gogh immersives in Kensington Gardens and in Shoreditch. The Shoreditch one was the better of the two, but both were inferior to Atelier des Lumieres in Paris.

The Paris venue is much bigger. The projections range continuously over the entire wall space and the whole of the floor, and the art seems to gain depth from being projected onto hard surfaces. It’s darker, which helps. The show was also longer, I reckon that c7 minutes had been cut in London. And there are shorter secondary programmes. With Van Gogh there was one on Japanese art and it was dazzling.

The touring versions here are better than nothing; I will be going to see the Monet and the Dali ones because Covid stopped me from travelling to Paris. But I’ll be back on the Eurostar for Cezanne and Kandinsky later this year.

I wonder if anyone is considering an immersive exhibition of the works if Francis Bacon? Tourists might complain too much about the works being smeary and weird.

My enjoyment of art started with the cheap tacky prints of Van Gogh and Cezanne dotted about my parents house in the ’70’s.

Since then i’ ve been luck enough to visit many of the prestigious art galleries in Europe and the US.

If anyone goes to these inmersive pop ups and gets a better appreciation and love of art, then these type of exhibitions have done their job.

And let me tell you folks, the prestigious galleries aren’t all champagne flutes and raised eyebrows. Unless you plan ahead and know the quiet periods It’s still queues, sweat and elbows and a tacky gift shop at the end.

Concentrating on what’s in front of you means actively barging through the crowd to get up close.

Don’t let the art snobs spoil your fun.

Art doesn’t have to be in a gallery or in a dusty dull book.

One statement you will see in art galleries (especially when the art is contentious). “The artist here is forcing you to think about what art actually is”

The same statement applies to immersive galleries.

Immersive experiences have been part of art. In the late sixties/ early seventies in Sydney I was in art class with the daughter of one of the creators of the “Yellow house” which was cutting edge in immersive art. Artists have long picked up and experimented with new media. Calling the reproduction of an artist such as Van Gogh’s is more in line with lining promoter’s pockets than an art experience. Immersive experiences as an adjunct to an exhibition can have power, one that comes to mind was an installation about the babies lost in the female factories where in a darkened room there was a large arrangement of white hand sewn baby bonnets set out as grave markers with the names of the babies who died screened on a permanent scroll across the ceiling and down the wall. Many museums now incorporate immersive experiences with their exhibitions that can add to understanding but they don’t call it art.

Although opportunities to travel to see some artworks are opening up, remember that artworks can travel to a gallery near you and are well worth the wait, seeing Van Gogh’s, Monet’s or Renaissance masters work or indeed Tutankhamen’s gold mask in person in block-buster exhibitions were far more rewarding than digital graphics of said items. In fact, a sculpture that is so well known reproductions are passé moved me to tears when the authentic Rodin’s The Kiss was shown in Sydney.

Immersives may be a stimulating introduction to art for the uninitiated but unless they are genuinely unique, not reproductions they are not art, merely a commercial enterprise for fleecing the pockets of the public.

These so called immersive exhibitions are only OK as side shows to other primary gatherings. I saw the Van Gogh one a couple of years ago in the Athens Concert Hall and sadly it was an utter disappointment and waste of time and money.

Art work should be protected from this form of digital thing.

I take it you’ve never been through the gift shops at the Prado, Tate, Louvre, Uffizi then?

Colorful powerpoints run by art carnies.

That’s one opinion.

The other opinion is that your type of comment is high handed, elitist, art snobbery of the worst kind that disengages people who might otherwise take a ground level interest and work their way up.

Hey, let’s keep it civil here. I wrote this article because there are strong opinions on both sides, neither of which is totally right or wrong.

As a pensioner, I’ve witnessed this trend for (fairly) minimal displays, especially in museums. And I must admit, I much prefer previous displays, where you get to see much more.

I recently visited the Science Museum, and I was shocked at the lack of exhibits, when compared to the sheer quantity of items on display as a teenager.

My verdict? plenty of audio-visual interest, but not enough substance.

I went to the Van Gogh immersive experience exhibition in London with a friend. It was ok but the wierd grammar on the information boards was a bit off-putting from the start and the whole thing had a rather amateur air about it. The concept is interesting but you can see real Van Gogh paintings in London without all the hype and over-priced ‘gifts’. We still had a lovely day out.

I recall something kind of similar way back in the 80s, at West Midlands Safari park, of all places.

Whilst it wasn’t as technologically advanced the principle of an immersive experience was pretty much the same – a large blue dome you sat in, laid down in whilst audio visuals played via large cinema projectors that covered your entire field of vision. There was a rollercoaster and i think a plane doing stunts etc. then ambient music and abstract patterns and the like

Interesting but after 10 or so minutes you needed to concentrate to immerse yourself – if that makes sense.

Titanic: The Exhibition (which I believe has just closed in Canada Water, London), is one of the worst ‘exhibitions’ I have ever been to.

Cynically marketed and put together cheaply, it has left such a bad taste, I will be making sure to avoid all Musealia or Fever events in the future. There was absolutely no element that could be considered immersive, cheap recreations of cabins, corridors and some frosted over pipes purporting to be an iceberg.

Add to that an audio commentary with numerous pronunciation errors and misleading artefacts and you have one terrible experience that I would strongly advise avoiding at whichever city it next pops up in.

So… not unlike James Cameron’s film of it then?

On the way out you can buy a bucket hat with Starry Night on it. It’s what Van would have wanted. Great for kids but adults give it miss.

The idea of an overpriced bucket hat stitched by people on slaves wages half a world away being seen as a fitting memorial to his art may well have been what pushed Van Gogh over the edge as he sought some brief respite from plaguing depression when painting Starry Night but then realised the futility of it all

I think you can buy scream masks at Edvard Munch exhibitions and people regularly take selfies infront of piles of human hair and glasses at the AuschwitzBuchenau memorial.

Words fail me.

I’m concerned by the health risks and exclusionary effects of the addition of “smells” (fragrances) to these exhibitions. Fragrance formulations each typically contain several hundred ingredients, chosen from a pallet of thousands, many of which are hazardous to human and environmental health. A good number of these ingredients aid persistence, or dispersal or have other effects not directly related to the actual smell obtained.

With no requirement to list the ingredients, with little research on the risks and none on the effects of combining them, the suspect ingredients of fragrances are increasing being inflicted in so many ways onto unsuspecting consumers, in highly fragranced personal care products, area atomisers, and “forever fragrances” in laundry products. Artificial fragrances used for “immersive” experiences just add to the risks.

The cumulative effect is slowing showing; every year the number of people who have become sensitised to perfumes and other related chemicals is rising, now to around 34% of the general population in America & Australia. This is a 3% rise on seven years ago. These are people who suffer clear adverse health effects from exposure to fragrances. Effects range from dizziness, headaches, nausea, vomiting, sneezing, asthma, rashes, migraines, neurological symptoms of varying severity, paralysis, brain fog.

Once a person has become sensitised, their symptoms and responses may initially be mild, but with repeated exposures, those response symptoms typically continue to significantly worsen over time. There are no effective treatments known, the only helpful recommended recourse is to “prudent avoidance of triggers”.

For people already sensitised, immersive exhibitions (no matter how extraordinary) will clearly not be worth the the risk. Yet another aspect of public life that excludes and puts people with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity at risk every day. For people not yet sensitised: there’s still risk. Just less clear.

I certainly think that immersive exhibitions are a great way to break down gatekeeping barriers that museums have locked themselves behind for centuries, mostly for colonial reasons. In a way, immersive exhibitions break the ‘do not touch’ rule, and invite anyone to interrogate the art not only emotionally or academically, but physically, too.

But I’m unsure whether we should be physically and technologically immersing ourselves in the art of those who had no intention for it to be experienced that way. For museums to seek out a private license to technologically display Frida Kahlo’s art, for example, and then charge the public to enter it, completely goes against Kahlo’s anti-capitalist beliefs; the mass production of her art is a perversion of her art.

For an immersive exhibition to be more ethical, I believe it should display the art of artists who intended for it to be displayed that way. Intention is key.

Saw the van Gogh and Klimt lightshows in Paris in 2019. As a generally non-arty person, I quite enjoyed it. Made a weekend of it with the Da Vinci exhibition at the Louvre as well. I doubt I would see it again, though. Once was enough.

Digital art has been driven by funding from tech companies for a long time. I remember trawling through the pages of Artists’ Newsletter decades ago seeking ‘artist opportunities’ and rarely finding any except for video and sound artists. If Van Gogh and Klimt were starting out today where would they find the support to continue working?

Digital immersive installations are entertaining and have a place in introducing audiences to visual artists but there’s nothing like the real thing, and it is not necessary to rely on hi-tech to experience it.

I went to the Van Gogh one in Warsaw, Poland. On the promotion photos it looked great, but they were taken in a place that had some kind of screen system in the floors. I’m sure that it was great there, but where I went; it was just some projections on the walls. Sad…

Seems to head head-long into sensory over-stimulation; technology used to try desperately to squeeze every last drop of potential ‘experience’ out of pieces of art.

Not sure if the artists want their audience to experience from their art (interpretation is in the eye of the viewer) but this seems to be an unnecessary jump from one thing to another: from interpretation-contemplation to ‘put your money in the slot and get your 30 dollars worth’ then sigh and wonder if you’ll have a high-street burger or a designer coffee next. Art as a consumer desirable taken to extremes.

And art less as a source of enlightenment. This isn’t so much about what binds us to art but what we can get out of it as rampant consumers burrowing our way like ravenous termites through another few dollars.

Signed: a grumpy granddad.

I’m with you. Signed: a grumpy not-quite Grandmom yet, but fingers crossed.

I’ve only been to one immersive art experience: going into an inflatable tent, getting naked with the artists and watching a film of them naked. Quite fun but not sure how far I’d call that one “art”…or rather if (m)any of the participants were participating for art or for floods of free booze, a social media post and an anecdote.

As a former art student, I can tell you it is the latter. Even among artists. Or maybe especially among them.

And I thought some of my immersive experiences at the Fringe were weird!

Each advance in technology in respect of culture seems to go through a similar cycle: first it is treated as an amusing plaything but not the real thing; then, as it challenges preconceptions as to what art is, strenuous critical effort is put in to pointing why the “new” simply isn’t as good as the “real” thing; then it becomes the mainstream. Witness the trajectories of photography, film, video and recorded speech and music. I sense that the reviewer is at the second stage of the cycle. It is inevitable that the amazing advance of digital and imagining technology would spur creative work that explores the potential of that medium, taking their work beyond established norms and becomes a thing in itself rather than just a medium for accessing the past. And if in the process it gives artists new types of audiences and also new sources of income so much the better. Strap on your goggles and buckle up! It’s going to be an exciting adventure.

I think this type of gallery is an interesting take on art. I’d like to go visit it.

Personally I think there’s enough art in the world already.

The possibilities for immersive exhibitions are endless.

Not everything can be free, art is a business, always has been and there is no right to do “art” and be paid by everyone else.

Immersive art? In my time we used to call them parties. We were really interested in the pretentious side of things.

I learned much about Frida in middle school, its interesting to see such a well written article on her trespasses since then.

This article is definitely sparking my interest in art once again, Thank you for that!

It’s not making fine art accessible though is it? It’s continuing the notion of spectacle, and reproducing hw much fine art is seen already: backlit digital versions on screen or through the viewfinder of a digital phone or camera.

People need to learn how to look and spend time with paintings. This isn’t going to help.

Art is, and always has been, subjective. I, for one, enjoy immersive art as well as art hung on a wall behind a frame. While immersive exhibitions may be presenting a new way of enjoying existing works, probably changing the artists’ intended impact, I believe I do not see it as art being ‘ruined’.

After all, I would not mind lying on the floor looking up at Van Gogh’s starry night making me feel like I am dreaming with my eyes open.

Wow, really interesting dive into immersive art museums. I’ve never been to one, but I’ve seen many advertisements for Van Gogh in particular. I think there are certainly two sides to this story, and you analyzed each perspective masterfully. I love art, and to me to it seems immersive museums are also an extension of joy for art.

I don’t know if I’m missing out on these immersive experiences, but the concept never attracted me.

I found your insight into Christopher Lasch’s work quite interesting. I will check his book out soon. Thank you for a well-written piece.

Lasch is definitely a writer that has some silent prestige.

This is a very intriguing analysis! I have never been to an immersive art exhibition before, but I can understand why some traditional art lovers have reservations about it (though, like you said, new methods to experience art should not be stifled). Immersive art is probably cool, but I think I might find it a bit of an assault on the senses after a while. Looking at a “static” piece of art can allow for a more direct communion between the viewer and the artwork. It gives me space to conjure up my own thoughts and feelings instead of turning the art itself into a purely aesthetic performance I can passively consume with ease.

A very intriguing analysis of Christopher Lasch and The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in An Age of Diminishing Expectations. The application of his ideas in regard to immersive art makes for an interesting point of view.

I would agree with your sentiment that immersive art is interesting and engaging at the moment but quickly loses some of its grandeur. Traditional art has some intimate qualities that the artist includes that tend to be washed away by immersive art and the desire for Lasch’s narcissists to have their “Instagram moment.”

Both immersive and traditional art have their target audiences and their own merits, and I find that in a world of moment-to-moment gratification immersive art is a logical next step. I find it sort of funny how Lasch writes about “Diminishing Expectations” when in a way one could argue the opposite is happening, with people constantly searching for the next biggest thing to hold their fleeting attention.

That’s an interesting take on it, and one that I resonate with. I went to an immersive Van Gogh experience last year and walked away feeling that the topic was a little misplaced. Here was an impressively constructed soundstage being used to display visual art… slightly confusing, no? I could see a simulation experience being portrayed here, concerning astronomy or biology, for example, as a way to engage learners with a topic, but an enhanced and animated canvas for a slew of paintings with sound effects in the background felt like the space could do more. I do hope the spaces will be pushed to their fullest potential and utilized for more manner of displays and exhibits.

I think the fact is that immersive exhibits satisfy a different experience than going to a traditional museum. They’re displaying the titans of the art world for a reason, they’re not necessarily for people who “enjoy art,” they’re for people who enjoy a good time – it’s a new activity to do and can you fault people for thinking that standing in a moving Starry Night would be a cool way to spend an afternoon? Personally, I think it’s cool to see art we’re all familiar with in a newer, more modern performance art style. It opens a lot of minds to a multimedia art experience, and the mainstream audience that these exhibits are for might check out some smaller artists who DO incorporate lights and sounds into their exhibits. We don’t have to be scared of new things, guys!

I understand the arguments in this article but I think that firstly, narcissism shouldn’t be used as a theoretical framework for understanding other things. Narcissism is a personality disorder, and it should be treated as that, nothing more or less. Secondly, as an art student I have mixed feelings about immersive art. I think to some extent, they combat the elitism and inaccessibility present in so many art spaces. I’m also someone who works a lot in creating art that is exclusively digital, so some part of me thinks this aversion some people have might be coming from a place of purism. On the other hand, I don’t want to see art that was cynically engineered to be commercial and instagrammable.

I find it useful to think about the ways that ‘traditional art museums’ are also immersive experiences (and I’ll tip my hat here to Seema Rao who first pointed out this way of thinking). A ‘traditional art museum’, with its white walls, hushed exhibitions, spotlights on paintings, guards in uniforms, monumental façade, is also an immersive experience: it immerses you in the power of the institution. Typically it’s immersing you in a White colonial history, a patriarchal history, a specific cultural framework.

I think that the success of immersive art exhibitions will heavily depend on the person experiencing them. I personally went to one based on the work of van Gogh a few years ago. In my opinion, it wasn’t enjoyable to me. I’m sure that others had a different take, but to me, the same combination of visuals/audio could have been in a Youtube video format for free instead of standing around for $50. To each their own, I suppose.

Immersive experiences have been rising in popularity in recent years as technology becomes increasingly advanced. The idea that Immersive experiences are ruining art is an extreme viewpoint and there are positives to intertwining classic art with technological advancements. Although I believe art should be appreciated in its raw and uninhibited form, technology makes these cultural contributions more accessible to those who might not have the means to view them. Will viewing a masterpiece on the big screen have the same effect on people who view one in person? In my opinion, no, however, it’s better to view them at all rather than be oblivious to them. Being able to see a work of art in its natural and organic form leaves unforgettable impressions on us that technology could never compete with.

Sensory engagement is the way to redirect bias stored in memory. Research happening in sleep studies, especially using immersive sounds, smells, and nudges that engage the brain in this visceral way, does wonders for human beings. And what better way to engage youth in art by getting their entire bodies to emerge in these arworks? Not many people will even be able to see, smell, touch, or hear the birds in Monet’s actual garden! So this is a way to help those less fortunate, and fortunate imagine a world, beyond something static.

Extremely interesting and well-written article. The application of Lasch’s concept of narcissism here was fascinating, and explained much of my personal discomfort with how art seems to be consumed, displayed, and interacted with in this age. While I don’t think art of any kind should be ‘gate-kept’ and locked within the walls of an institution, there was definitely a sense of the art being cheapened when I attended a van Gogh immersive exhibition. One of the main things for me though was just how out of place the music was – they played only very well-known and frankly ‘comfortable’ pieces of classical music that complemented neither the artworks nor the artist’s time period. I thought that immersive art exhibitions could be much more plausible, enjoyable, and even beneficial to the understanding of the art, if only a bit more thought was put into the overall experience, rather than it just being a palatable opportunity for an Instagram post.

I don’t think the ‘gate-keeping’ criticism holds, either. These exhibits are more expensive than admission to most art galleries.

As the author said at the beginning, the artists chosen for immersive exhibits are cultural symbols— chewed up and spit out. By removing them from their context and making them an Instagrammable experience, they’re further reducing the artists to symbols and negating the point of the aesthetic emotion. It’s a disservice to the viewer and the Great artists on display.

I would even extend the application of Lasch’s concepts to more novel immersive exhibits like Meow Wolf, which are just “selfie museums” pretending to be modern pop art installations.

The temporary nature of the immersive art exhibitions was an interesting point, in how the art is displayed in pop up buildings, warehouses or other such places, making the exhibitions appear limited and thus desirable to witness. It’s also interesting how the art is placed in new settings and in new mediums, as a form of almost re-contextualisation, which may not work for some audiences, but can be more accessible for others.

I wanted to go to one but someone didn’t want to go to the immersive one.

My major concern with immersive exhibitions is the sensory overstimulation they might produce, which, while tolerable for most people, could lead to a kind of desensitization to more tranquil experiences. As people become accustomed to highly stimulating environments, they might find it harder to fully appreciate the stillness and subtle details of traditional artworks, like the brushwork in a painting. In a world where we are already overstimulated by constant engagement with our phones, these exhibitions could further amplify that trend.