In Defense of the Conclusion to “The Little Mermaid”

The conclusion to Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid” is one of the most misunderstood, misinterpreted and maligned in Western literature. Does he go too far, offering a needlessly bleak and tragic conclusion to a tale which doesn’t warrant it? Or does he fail to go far enough, stopping short of the tragic conclusion the story seems to necessitate, tacking on a marginally happy and unsatisfying conclusion? While both of these responses to his ending capture something significant as regards Andersen’s purposes, they miss something fundamental when it comes to the central theme Andersen wished to convey. And when we understand that theme, we see the conclusion Andersen provides is the only one which can be considered dramatically fitting.

The Story as Compared with its Adaptations

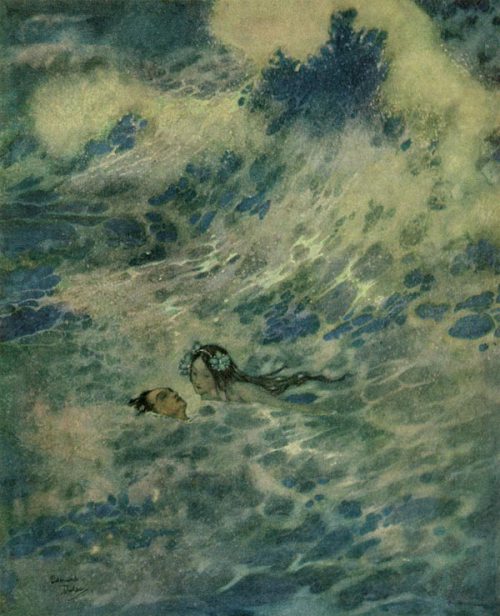

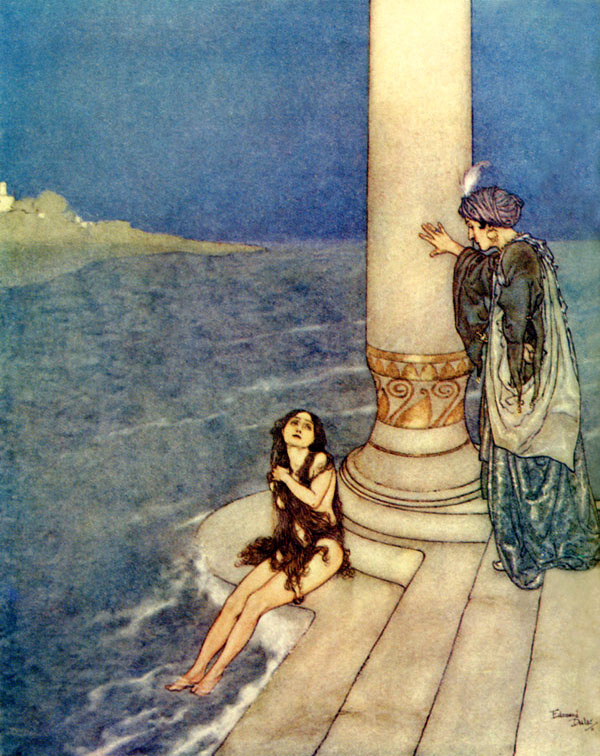

Those familiar with the Disney adaptation of Andersen’s story are often unprepared for the harshness of the mermaid’s journey. The sea witch cuts off the mermaid’s tongue as payment for giving her legs, rather than magically giving up the glowing sphere that apparently constitutes her voice; when she walks on land, “every step she took was as the witch had said it would be, she felt as if treading upon the points of needles or sharp knives”; the prince, as in the film, falls in love and weds another, but, unlike the film, the bride has nothing to do with the sea-witch and nothing thwarts the wedding. The mermaid fails to marry the prince. The witch gives her the opportunity of returning to the sea if she kills the prince, but she refuses, falls off the boat, and presumably drowns. But she doesn’t die: instead, a group of spirits called the “Daughters of the Air” come to her and she becomes one of them. These spirits have no immortal soul, but they earn one through three hundred years of good deeds toward mankind. It’s not the ending most expect from their familiarity with the more conventional Disney film, but it’s also not the tragic ending many expect from hearsay, either.

Those who are not shocked by the mermaid’s failure and accept the story on its own merits are nonetheless sometimes disappointed that Andersen does not go farther. That is, they argue that the events of the story are building towards a tragic conclusion, and having these “daughters of the air” float in at the end is an unrealistic tack-on to prevent the story from being wholly downbeat. The crux of their argument rests with the mermaid’s bargain with the sea witch. At this point, the mermaid has seen the surface world, rescued the prince and fallen in love. The only way she knows to obtain the legs to live on land to persuade the prince to marry her is to go to the sea witch. The sea witch had little sympathy for the mermaid, and tells her point-blank that “it is very stupid of you [to want this], but you shall have your way, and it will bring you to sorrow, my pretty princess.” And her prediction is unhappily accurate, the mermaid suffering excruciating pain—both physically and emotionally—pining for the prince who does love her, but never as a wife, and never realizes the extent of her love. Indeed, on this reading, one could put the story into an Aristotelian framework quite nicely: the mermaid is a girl better than average, who, through the hubristic attempt to gain an immortal soul by her own efforts, loses all the good things she has and, inevitably, dies.

Andersen’s Christian Imagination

This reading, though not wholly invalid, misses something crucial about the sort of story Andersen is telling. If the opposing reading is correct, then Andersen’s ending is almost cruel in its inadequacy, giving the mermaid a weak “consolation prize” after the misery she suffered on land. But the ending Andersen does give masks something more profound than merely tragic conclusion would give. Andersen’s stories are called “fairytales”, but, unlike the Grimm Brothers, who mostly recorded old oral folktales, his were wholly original and imbued with his own idiosyncrasies as a writer. His stories run the gamut from the joyful to the mellow to the devastating, but one thing that remains perfectly clear throughout all of them is a pervasive Christian worldview. Some of his stories refer to God, Christianity, and even the priesthood explicitly, like “The Marsh King’s Daughter.” Others are more subtle, sometimes referring to Christian doctrines, but not bringing Christianity to the forefront. “The Little Mermaid” rests somewhere in the middle. It does not make much of Christian doctrines explicitly, but the understanding of the immortal soul, of heaven, of the place of individual virtue in the context of salvation are all woven into the background of the story. When one understands the Christian imagination permeating these tales, one can then see more clearly why Andersen ends this story the way he does.

To begin, her desire for life on land is not derived solely from her desire to marry the prince, but rather rests more fundamentally on her desire for an immortal soul. For, in Andersen’s story, mermaids don’t have immortal souls: rather, they live for three hundred years and then dissolve into sea foam. While the mermaid’s grandmother counsels her to “be happy…and dart and spring about during the three hundred years that we have to live, which is really quite long enough,” the mermaid asks “Why have not we an immortal soul?…I would give gladly all the hundreds of years that I have to live, to be a human being only for one day, and to have the hope of knowing the happiness of that glorious world above the stars.” She is unsatisfied with the pure temporal happiness which seems to satisfy her grandmother and the rest of her kin, but her grandmother does give her a piece of advice that sets her off on her sorrowful journey:

unless a man were to love you so much that you were more to him than his father or mother; and if all his thoughts and all his love were fixed upon you, and the priest placed his right hand in yours, and he promised to be true to you here and hereafter, then his soul would glide into your body and you would obtain a share in the future happiness of mankind. He would give a soul to you and retain his own as well; but this can never happen.

Thus, the mermaid has much more at stake in her endeavor to become human than did Ariel. It’s not simply that she wants to marry the prince, or escape her situation for something new or better, but rather she doesn’t want death to be the end. She wants to experience the hope, the joy, and the glory that men do in obtaining eternal happiness. She wants immortality.

Now, Andersen does not seem to present the desire for immortality itself as a bad thing. However, as has been before discussed, the way she endeavors to obtain this immortality is questionable at best. She did attempt to achieve immortality by her own efforts, which is a losing proposition from the start. But, this derived, not from a prideful presumption, but an uncircumspect naiveté. Her escapade on land brings suffering and loneliness, and her project eventually ends in failure–but she does not take the ‘out’ provided which would be exponentially worse than anything she had before. As the Daughters of Air tell her when they snatch her from the jaws of death:

After we have striven for three hundred years to all the good in our power, we receive an immortal soul and take part in the happiness of mankind. You, poor little mermaid, have tried with your whole heart to do as we are doing; you have suffered and endured and raised yourself to the spirit-world by your good deeds; and now, by striving for three hundred years in the same way, you may obtain an immortal soul.

No one can strictly speaking earn eternal life, but she does in a sense earn it by throwing away any chance she has of mortal happiness by refusing to kill the prince and accepting death. It is by accepting death that she gains life. As Christ says in the Gospels, “He that findeth his life, shall lose it: and he that shall lose his life for me, shall find it” (Matthew 10:39).

Conclusion

Thus, it is more dramatically fitting for the mermaid to be given a new lease on life rather than dissolving into sea foam. She should not fully succeed in her quest, but neither does she merit annihilation, for she gives up everything rather than salvage whatever temporal happiness she can through an act as despicable as murder. She tried to attain eternal happiness through her own efforts and failed, but she threw away all possibility of happiness and then gained more than she could have hoped for before. It is her sacrifice, a sacrifice that would quite literally end in her annihilation that, paradoxically, makes her worthy of eternal life. Were Andersen to end it tragically after the sacrifice she made would be cruelty on the part of Andersen, and therefore he was right to consider the tragic ending a “mistake.” Now, we can critique the device of the “Daughters of the Air” itself, but the conclusion required something of that sort in order to properly end the story of this poor Little Mermaid. Anything different, “worse” or “better,” would have been somehow “wrong.” Ending it with the conventional “happy ending” of marriage to the prince would somehow have been “cheap,” giving her what she wanted when she used questionable means to get it. A more tragic ending, however, would be excessively cruel, rewarding her hopeless sacrifice with the stark finality of a mermaid’s death, which we cannot say she merits either. Therefore, albeit in counter-intuitive way, the conclusion that has come down to us is the most dramatically fitting conclusion Andersen could give this tale.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

There is something funny I realized just recentely, as I started reading all those stories I read as a child: as I grew up in the communist country, where religion was prohibited, all the references to God, angels, Heaven, etc, were taken out of these stories, so until recently I didn’t even know they had religios subtext or even direct content. So, now I am thinking – what else did they leave out of these originals, that was politically incorrect (literary)?

Disney movies were mostly unaltered, but they didn’t have religious content, unless I am mistaken again!

Andersen’s fairy tales were translated including the names of the characters so in some cases I had to read the story to find out what is its real name.

That’s very interesting. Andersen’s tales are usually very, very religious. I can’t imagine Andersen’s stories without the religion–it’s such a central part of his approach. I didn’t realize that censorship had extended so far.

Can I ask which communist country that was, just out of interest? (The Russian translations by Anna Ganzen are, thankfully, totally fine. They did go “soft censuring” with Andersen by adapting most of the kids’ books, but then, they are adapted everywhere).

I have never considered the ending of the Little Mermaid to be her death, for all that she dissolves and becomes ethereal. Death, to me, is much more permanent, and this event was presented as a transformation rather than an ending to her life. It’s still a bit of a sucker punch what with her not marrying the prince, but Andersen seems to have pulled his punch at the last minute by giving her 300 more years of “life” and an eternal soul at the end (no princes required!).

I remember taking a set of Andersen’s books once I was in my twenties, and reading few stories, less popular and known – they were so utterly sad, I got depressed right there and quit! For the first time I realized his stories are not for children, they are for grown ups, and only those who can handle it.

I think the story shows the opposite if anything… that the voice is powerful… that its loss makes us weak…

All the fairy tales are disturbing in some way.

I read the Anderson version of the Little Mermaid before I watched the Disney cartoon. I was extremely perplexed at why they were singing all these jolly songs under the sea until I realized they were giving it a happy ending. I was 6.

I’m not even certain what Andersen was trying to say. Love at first sight is bad? But, the Little Mermaid gains her promise of an immortal soul through her one-sided devotion. Too much sacrifice on one side of a relationship is bad? Unrequited love is redemptive?

If the story is meant as a warning, I see some of Andersen’s point as valid. Girls who fall in love at first sight usually find out the guy wasn’t who they thought he was. On the other hand, in real life, we learn from our sad, first crushes and move on. We don’t make tragic choices that lead to having to decide whether to kill the ex-boyfriend or die ourselves.

I wonder what the disney movie would be like if it did follow the original ending.

Probably not for little children. Actually, the original stories weren’t meant for children to begin with.

Who else knows the Japanese adaptation of The Little Mermaid?

I remember it!!! I prefer that version despite its sad…

I still have it on VHS. I used to watch it all the time when I was a kid. That was my little mermaid growing up.

Want to make it even more heartbreaking? Hans Christian Anderson wrote this as a love letter… to a man (he was bisexual). When he learned that the man he loved was going to marry, Hans confessed his felling but got rejected. After the man married, Hans wrote the Little Mermaid and sent it to but never got an answer. The story is a metaphor for a love you can never obtain, even that you are so close.

I did read a couple of things addressing his sexuality. Er, unless they were wrong or more evidence has come up since I read about it, I gathered there’s a lot of debate with evidence that can be cited for anything just about anything, ranging from bisexual to asexual. Whatever his orientation, I would say he was never comfortable with being in love, especially with the risks that come with being in love. I just have no idea if that was fear of forbidden love or terror at the vulnerability that comes with being in love.

Great article! I think Little Mermaid has gotten a bad rap and am glad to see you defend the story.

Ophelia said, “They say the owl was a baker’s daughter. Lord! we know what we are, but know not what we may be.” (4,5,32-3) The baker’s daughter’s fate: being turned into an owl, was the consequence of what the daughter should have done but didn’t do: repeatedly no less. Conversely, Ophelia’s fate was sealed because she effectively lost the ‘name of action’ and stayed a prisoner to the will of all who sought to command her: which ultimately cost her her life in exchange for nothing. The Mermaid, however, knew what she was, and also knew she wanted to become more (whatever that might be or whatever it might entail), and she gladly traded 300 years of tranquil existence for just one day of true living (“to thine own self be true”). And like Homer’s story, The Iliad, Achilles chose to live for glory and die young versus live long and die in obscurity.

The Mermaid embodied action, in the spirit of Achilles, even though the price of her decision required that she enter into a [kind of disinterested] ‘Faustian bargain’ with the Sea Witch. The cost of such a bargain was that The Mermaid paid the theft with her life, but it secured her a trip to the ‘undiscovered country’. In that respect she personified the hero’s journey; tragic on first inspection, but after considered reflection the archetypal nobleness of The Mermaid’s convictions stands in stark relief against those who chisel for advantage as did the baker’s daughter, or those who blindly conform even to their own detriment like Ophelia. The Mermaid’s story is inspirational.

I have to admit that I absolutely hated the Disney version of The Little Mermaid. My childhood analysis was here was this spoiled brat that rebelled against her family, legacy, and title to jump into bed with a hot stranger, and she got what she wanted in the end. Also, happiness depended on a man and his love. The moral of that weak story line is not only disappointing but also a poor message for children. That being said, I never read the original story by Hans Christian Anderson. After reading your synopsis and unique critique, I have fallen head over heels for the story. I am a sucker for a story wrapped with theology, and I think that your interpretation of the conclusion shows that she got the happiest of any ending suggested. Also, I think it is worth mentioning that the joining of souls through marriage or “the two shall become one flesh” comes straight out of Matthew 19. Thus, the grandma’s solution is less about needing a man to be complete and more a testimony of the power and immortality of love between spouses.

I had only watched “Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Mermaid (1975)” on youtube and did not read the story itself. I’ll make it a point to do so in the future so I can get a better grasp on the Christian themes you bring up since they originally escaped my notice.

I enjoyed this article. I read Andersen’s stories when I was very young so their sudden twists in plot struck me hard and stayed with me as a morbid fascination.

I love deeply Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales, and, as with all the authors I LOVE I’ve been feeling a strong identification with his characters since I was a child. He is still one of the writers that I need to mention when talking of what influenced me, my choices, my writings.

I loved his tales when I was a child, The Ugly Duckling has always been one of my favourite, because it was sad, and because there was a lot of hope in that sadness. The same for the Little Mermaid.

I think Anderson’s tale was a testament to the side we never hear. “Not everything has a happy ending, and life isn’t perfect. You can love someone, love them enough to die for them (and maybe that even makes you happy) But love really doesn’t conquer death”.

I’ve wondered why he wrote it the way he did. Could be something so simple as he had a bad day or his wife cheated on him. I tend to think he just got tired of hearing “Happily Ever After”.

It’s been a while since I read the Andersen story, but what I still carry from it is the absence of any regret on the mermaid’s part.

Hans Christian Anderson wrote such great fairy tales.

I have to recommend the book ‘Mermaid’ by Carolyn Turgeon, which is pretty faithful to the structure of the Anderson story but focuses a lot on the story of the girl who finds the prince on the beach, as much as the mermaid who longs for a soul – and the connection between the two of them.

Wow! Didn’t know. I even was thinking of writing a similar story (in my native language) about that. Pretty curious now! Thank you.

Wow! Jonell Arie. Didn’t know. I even was thinking of writing a similar story (in my native language) about that. Pretty curious now! Thank you.

Andersen traumatized my childhood. Besides killing off mermaids, he chopped off the feet of little girls whose only crime was wanting a pretty pair of shoes, burnt up fir trees for wanting to feel special on Christmas, and had a prince disguise himself as a swineherd for the sole purpose of seducing the princess who rejected him so he could abandon her after her father cast her out for being caught kissing a swineherd. Although, I still like the Snow Queen.

Would you agree that the audience has been so spoilt by inevitable happy endings in films and cartoons that when a not entirely happy but, as you say, the most dramatically fitting conclusion is revealed, the reader / viewer is shocked?

Comparing and contrasting Disney vs. Anderson is a topic I will never get bored of. There is a lot to be said about the different perspectives and possibilities.

like post

Fantastic article.

A funny thing happened to me few weeks ago: I was talking to this young lady who will be a part of this new puppetry performance. She is in her early twenties. I asked her which version does she like better, Disney one with “happily ever after” or original, where Little Mermaid dies. Her eyes just popped out:” Little Mermaid dies?” She has never read the original. I felt like I just told a five year old kid there was no Santa. (I also remembered that episode of “Friends” when Phoebe realizes the dog will die in “Old Yeller”, which her mother never let her see to the end as a child. That movie sure scarred me!)

A whole new generation is growing up, and their starting point will not be Andersen’s version, but Disney one. It’s a phenomenon on its own.

Please write more work. Your articles are great.

They shouldn’t change the plot of Little Mermaid, because it is really heart-throbbing and immensely sad. This kind of soft agony makes a great story.

Whereas sleeping beauty and Cinderella are just creepy.

Personally I like the Anderson version better.

Thank you! Well said. I appreciate the analysis. Too often we want a “happy” ending that completely negates the point of the art.

It was written for a more spiritual people, during a time that deep belief in God and the supernatural was more common and the hierarchy of Heaven was clearly defined. The little mermaid didn’t “die” but became effectively an angel.

I was never a fan of this story, due to its sad ending. However, Disney version didn’t make me happy either, I felt somehow cheated.

I love this analysis. I remember being quite puzzled by some of Anderson’s stories as a child. I still love him.

I’ve read most of the original fairy tales except for Hunchback of Notre dame. They are all pretty damn dark if you ask me…

Childhood ruined.

nice

Well said, the ending always seemed sad but suitable to me 😉

In my mind, the Disney version celebrates the virtues of “staying in ones place”, as so many of Andersen’s stories do, while simultaneously proffering the promise of Heaven as the reward for taking a chance, whereas the Disney version seems to celebrate risk, leaving open the option of success once one breaks boundaries. That said, while I like Disney’s message … I’ve always found their version to be a copout. Sometimes, risk is equivalent to sacrifice, after all …

I like the Disney one but I favor the original.

The disney version The Little Mermaid is gold , especially the songs and the art .. love the music score by alan menken but srsly id still love to watch a live action adaptation of the original story ( i saw the anime version too) and the fairytaler one [ was sad but amazing story]

I think I know the Fairytaler one…That’s probably my favourite adaptation of Andersen’s tale. The animation is beautiful, the voice acting is strong, and the ending is handled beautifully (“Tell them not to be sad. I’m amongst friends now, and everything’s fine…”)

She is not trying to win a prince, she is trying to gain a soul to enter heaven, something only humans can do. Her sacrifice at the end is the act that grants her wish and she does indeed have a chance to get to heaven.

I must admit that I was unfamiliar with Andersen’s version and I am now left wanting to revisit his works. When first viewing this topic, I wasn’t certain that I would enjoy this article–well I was wrong! You tie in the aspects of preconceived notions due to the majority’s familiarity with the Disney version; prominent themes of morality; and Andersen’s essential motif of theology. Thank you for opening my eyes and viewing this work in a different light!

Excellent article! You tied everything together wonderfully!

The Disney version is better than the original story.

Nothing compared to some of the Grimm’s stories that were NOT made into Disney movies. Like the Maiden With No Hands. He father chops her hands off so a creepy old guy will lose interest in her, then he kicks her out of the house.

I must confess I have not even read the original. Now I am intrigued.

Love it! You have me rolling this morning! Who needs coffee!!

I think one of the most interesting things about this story is the way is can, and has, been re-imagined into different times and cultures. The Disney version gives us a very “American Dream” approach to happiness. If you work hard and are good, you will succeed (and to beware contracts.) Even the description of Ariel as “headstrong” and Sebastian’s moral that “children gotta’ be free to live their own lives.” speaks to the place that individualism holds in the US psyche. When you look at Ponyo, you see a story about innocence restoring the balance to the world. Yes, Ponyo disrupts the natural order and is disobedient, but she and Sosuke also restore balance through a pure and innocent love. It’s such a unique framework, and yet it lends itself so nicely to retelling and re-imagining.

Very creative and an interesting viewpoint! I wasn’t familiar with Anderson’s version of the little mermaid, but I know that Disney often puts a much more childish and happy twist to their portrayal of fairytales. I do enjoy the darker aspects of fairytales and I’m really glad you explored this topic. Great read!

Great article! I thoroughly enjoyed it. This is a strong argument presented here, very well written and gripping.

Although I am bias to the Disney film version to this story, I do like your interpretation on how this version is most suitable to the tale. I like the idea of how “by accepting death she gains life” because even though she did not get the Disney style happy ending, she did get a happy ending by earning immortality.

The little mermaid is a subjective figure, as she decided herself to pursuit love at the price of suffering and losing her voice; and the kindness inside her made her lost the last chance to save herself, and eventually sacrificed for love. From losing voice and suffer every time she walked, we learned that sometimes gaining also means losing; sometimes it’s the right for you to speak, or to tell the truth.

The scene that the little mermaid turned into foams also got me wonder, would it still be a fairytale if it went the other way? If little mermaid killed the prince in order to save herself, she would have been a selfish and vicious person, and the love story would not be so attractive and moving anymore. So there is no best ending in this story, but maybe Anderson was trying to tell us, we can die for what we truly love, and we shouldn’t change who we are for anything.

I find the author’s argument in this article interesting. What stuck with me as significant is the author’s mention of the Christian undertones in many of Andersen’s stories, and in The Little Mermaid. With these Christian themes in mind, it’s interesting that the mermaid essentially sacrifices her earthly life and happiness to gain eternal life. Tying this along to the Christian theme that the author presents, the mermaid’s sacrifice mirrors Christ’s own sacrifice on the cross, in that both sacrifices merit eternal life through the price paid in earthly suffering.

I’m actually much happier with this ending, though I might be happier still if she died. I was never a fan of the Disney version, Ariel losing most points as an admirable princess for her selfishness, entitlement and trivial longings. I feel that Anderson’s message has to do with coveting. Ariel is a (walking) symbol for the-grass-is-greener cliche. Sure, many princesses seek out a world unknown to them, but for more substantive reasons and at lower stakes. Rapunzel longed for knowledge and her own sense of identity, questioning the reality fed to her by Mother Gothel (Allegory of the Cave motif). Mulan was driven out by the desire to defend family, and even Elsa sought out a haven for herself where she could do no harm. Ariel had a pretty sweet life and, despite the wise advice from everyone, including the person who would ultimately curse her, she still chose to covet. If anything, that’s Anderson’s Christian message. Count your blessings and avoid looking to the other. She rejects her place and role for no practical reason. At least the other princesses had noble reasons (at least, in the Disney versions). So ungrateful. “in everything give thanks; for this is God’s will for you in Christ Jesus.” 1 Thessalonians 5:18

Ariel – the first Millennial.

This is a wonderful and very thought provoking article. I remember reading the original story when I was really young and being upset that it wasn’t like the Disney version. I may have to reread it now that I can appreciate it.

I think I think this article is outstanding. Explained the story’s ending without retelling the entire story. This would probably be very understandable for someone who had never heard of The Little Mermaid.

I remember reading this when I was younger, but the grandmother’s speech seems extremely significant to me now when I re read it here.

I wonder what she was trying to say?

She defines Christian marriage as a way for the Little mermaid to get an immortal soul, yet the way the story turns out, it is clear that marriage is not a sufficient way to gain a soul (as the author writes, an improper method’).

I feel like there’s some subtext on virginity/fornication in those lines that we’re missing, not necessarily related just to the concept of the soul, but to that of the Christian doctrine as a whole.

I think that the overtones of Andersons story are more saturated in Christanity than many believe. The mermaid falls into temptation, makes a deal with the devil (sea witch) and thusly is punished, but more or less she repents and is absolved and is granted eternal life (after working for it, much like a disciple). Also apparent is the female agency that is taken away, the mermaid makes huge sacrifices in order to be with the prince and in doing so loses her voice/agency. What happens after is a direct result of his reaction to the mermaid and how he chooses another instead of her. The Prince is given the option of choosing with no consequences on his part, however the mermaid is given no options, she uses her agency in the beginning to strive towards something better than the accepted finality of sea foam death. Once she makes a deal with the sea witch she loses her agency and is at the mercy of the Prince. She fits into the trope of the good girl and instead of getting revenge on the man she does the right thing of a woman which is to be forgiving and kind, and so even though she gains a chance at eternal life, it is at the sacrifice of herself. I enjoyed your take on the story, thank you.

Personally I would never compare a child’s movie with such a beautiful tale. Not because I think one is better than the other, but they were created for different audiences. That’d be like comparing Adam West’s Batman movie to Christopher Nolan’ The Dark Knight. They aren’t even really the same characters. Regardless, I love Anderson’s version and felt satisfied with the way it ends.

This was a great read and fascinating interpretation of the suffering mermaid something to look into.

Great detail, I had no idea the extent to which this story went and I do find the ending disappointing.

Great analysis. This story as a whole is somewhat similar to a Christian redemption arc: seeking God, facing temptation, and through living well, reaching ultimate Christian salvation. It’s a strange sort of allegory for people, who, according to Christian teaching, are cut off from God through original sin, and through baptism, seeking, and living a “moral” life can find God eventually. So I agree that Anderson’s Christian worldview is foundational for this story, and every step of the mermaid’s journey is meant to be a step on his view of how life should be lived.

This is a wonderfully thought out article and I’m glad I had the pleasure to read it. After reviewing this article I realize most of my assumptions on the original “The Little Mermaid” were completely incorrect. The ending, to me, does seem satisfactory and quite appropriate now that I’ve seen it from a Christian perspective.

I actually agree. The ending was perfect for the tale. Anything worse would have been unfair to the character. Although was kind of bratty about not being able to live forever, she didn’t deserve to die tragically.

Okay now I have a question that without a doubt will have several opinions, but that’s okay. With it in mind that the two Mermaid tales we’re told with similarities as well as differences…my curiosity has me wondering about the cover art of the Disney version that created so much controversy surrounding the resemblance of the male genitalia embedded in the castle that it was removed from the shelves and recreated…do you think there is any significance to that as to either version of the story itself? Just food for thought…

I’ve always disparaged the ending of this fairy tale (partly because of how much I love the Disney movie of course) but your break down of why Andersen wrote this ending is brilliant. It’s still a little depressing to me, but I see why this was a meaningful ending for Andersen and important to what he was trying to say.

The original fairy tale is always better than the edited versions like Disney did. Not all fairy tales end happily ever after and this is how we learn life lessons.

Thanks very much for the interpretation. Although I had read watered down versions of Andersen’s “Little Mermaid” as a child, I never picked up on the underlying religious themes. The whole idea of an “immortal soul” is quite fascinating.

Thanks for this article. Although I know Disney would never have used The Little Mermaid’s original ending (heck, could they even get away with that?), I do think I’d like the movie more if they had incorporated some of Andersen’s style into the film. For instance, if Ursula had straight up told Ariel she was being stupid and would regret what she’d done, I might have more sympathy for Ariel than I do now. Additionally, I know Disney/Hollywood either can’t or won’t touch Andersen’s doctrinal undertones. But I would like Ariel much better if her desire to live on land had roots in something other than lust for a guy with whom she’s never had a conversation.

An interesting discussion. It is always important to remember the context of these tales and the framework in which they were created/recorded. The fairy tales of this period, both Anderson and Grimms, are as strongly moral fables as the Ancient Greek Mythologies or Aesop’s Fables. I think at times we forget that these tales actually had a strong purpose socially in the teaching of moral lessons and did not exist only as entertainment.

Exactly — historical context is important. I will invite you to view my suggested interpretation (below, posted Oct.6). That reading is certainly not the only way to find meaning in such a tale — but I will argue that it comes closer to seeing thematic issues in this story as people in Andersen’s time and country might have viewed them. Most of the interpretations I have seen are based upon literary-trained perspectives. But history adds another level.

I have always considered having her turned into sea foam is a forced happy ending to wrap up a “fairytale.” I appreciate how this article points out the religious implication of the ending. But adding “the Daughters of Air” at the last minute still seems forced

I read the story when I was 8 years old in the late seventies. I was at my godmother’s place and found a book with 100 fairytales. I read them all but it still feels like yesterday when reading this one. I was alone and couldn’t stop crying. Later I saw different versions on television, every time very close to the original story and was completely haunted. Also haunted by the connection between the mermaid and the girl he married. That seemed a very strong one. For that reason I never wanted to see te Disney version. I am European and am not found of Disney but that said I realize in the end they do the same as H.C.Andersen did, manipulate a certain way of thinking. I might not have understand the deeper meaning at the age of 8, I did understand I already had become that mermaid due to my sectarian education. I am very curious reading Mermaid from C. Turgeon now. Cause I indeed was always curious to know more about the life of the other girl. And the connection between both. Connecting between women. Something I always missed in Christianity.

The protagonist is facing obstacles that the antagonist initiated on her.

She has to overcome all of the adversities to sustain her power and status in the kingdom.

A stellar, promising and inspiring analysis.

Fantastic.

I have a bit of peace since I finally see the context and the fit of this ending. Somehow I just didn’t think the ending fit with the story thus it hit me out of left field and I was always so terribly confused. That just goes to show how important it is to read about what you read. I was missing something in my reading of the story that prohibited me from enjoying it fully. I’ll have to reread it sometime.

I enjoyed reading this article. I am glad you pointed out that ironically, the Little Mermaid accepted what she feared most, which led her to be able to gain a soul.

The Little Mermaid has definitely gained some bad reputation, because many people view her longing to be human based on her love for the Prince. But, I do believe that it is completely a wrong point of view to see her in. In the Disney film, she clearly sings to Flounder that she wishes to live in the human world and wants to know what a fork is used for. It is after she sings that she meets Prince Eric, which results in her deciding to finally take some action into her own hands and find a way to live in the world above the sea.

I just read the story. (I have had a book of Andersen’s works since childhood, but for some reason this story was missing.) There is one thing about the ending that no one has mentioned. It was this thing about the daughters of the air shortening their time before immortality when they hang out with good children, and lengthening it when they are with bad children. Isn’t this some kind of weird fable ending that tells kids to be good, or else you’re hurting the little mermaid?

The Little Mermaid and Social Class Control: [a historian’s interpretation]

There are many interpretations of this short story from Denmark in 1837; but one view of its meaning in its original context is that the Little Mermaid represents the potentially dangerous lower classes who had recently violently rebelled in the French Revolutionary period and then again in 1832 (and who were still a threat in 1837 – the 1848 Revolutions were coming). She wants to be seen as a human with a soul, and needs to be loved by the Prince to attain this goal. Her inability to speak in the story (this is allegory) is specifically utilized to show that the class divide is too large for her to be heard by a person from the elite social class; and when it becomes clear that she will never win his heart (though she might amuse him and can serve him), she finds the chance to slay him – her allied sisters (representing the danger of grouping up in an organized way within the lower classes) give her that opportunity. But she declines to kill the Prince to win her desired goal of a human soul; for this, she attains a chance at self-betterment in the afterlife. The meaning? Her reward in her afterlife is due to her decision not to steal the Prince’s life and to destroy the social world which kept her distanced from him. Additionally, she did not succumb to the temptation of using violence to serve her selfish personal desires. Thus, in the Conservative ideology of post-Congress of Vienna Europe, she adopts the Christian attitude that patience and doing one’s best to be moral and accepting of one’s God-given place is the way to win an eternal place in Heaven; this world might offer pain and seemingly unfair imbalances between people, but to tolerate this and do one’s best in life without trying to harm others to get something not intended for you – i.e., instead of rebelling against your fate – yields the most precious reward which exists (as was taught by the Church). This is precisely the message that Marx hated hearing from the Church (accept and be patient) – and it was an ideological tool created by the elites to keep the lower classes in their place (to deter revolution and rampant crime against people of higher social class who possess more wealth and privileges). The Sea Witch may represent the Devil who tempts the lowly to commit crimes for self-appeasement, but which destroy the soul (and the social hierarchy). Her “victory” is the victory of the elites in this 19th C. ideological indoctrination process. The story is an example of elite-imposed “thought-control.” [DTF]

PS: Notably, the US Disney version changes the ending – can this be a US rejection of rigid class divides?

Two modifications to the above: The Sea Witch might also represent God, who is testing the Little Mermaid (and the lower classes, if we accept that this is allegory) — in the same way that God tested Job by allowing Satan to work hardships upon Job. Second, the “victory” of the Little Mermaid in her afterlife (her chance to better herself and one day possibly attain Heaven) represents in this allegorical interpretation the victory of the elites in a more profound way: They apparently convinced Hans Christian Andersen that their agenda was the best way for the lower classes to approach the difficulties of life in the early-mid 19th century. Their only hope was to strive for the Kingdom of Heaven through their “proper” behavior in this life.

Great article. I absolutely love these types of insight into older folktales. For me, Andersen’s version of the Mermaid story sends some very powerful and ugly subconscious messages to young females of the day about who they were in this world and what they could and could not do. 1) As females they have no legitimate status or decent chance at life. They are literally lost at sea until a man chooses to marry them. 2) As females they must never go out of their way to choose a partner. They must wait to be chosen or risk losing everything.

The Disney version of The Little Mermaid has had a bad rep today, especially among feminists because she seemingly chooses to become human to meet Prince Eric and potentially be with him. But she was already curious about humans before meeting Eric and what actually made her want to change forms was her father’s punishment. If he was more accepting of her curiosity and provided her a space to explore, she may not have pursued becoming human.

So thank you – this helps remove the stigma around Ariel. You have indeed presented good philosophical breakdown and analysis of the Andersen’s version which sends a message that sacrifices, while they are emotionally and physically excruciating and can result in failure, does open doors to an unexpected but satisfying outcome. In retrospect, maybe Ariel was better off being a Daughter of the Air and more deserving of the role since was better than average to begin with.

I don’t understand why people object to an unhappy ending once in a while. Not every fairytale ends with “happily ever after.” The ending of “The Little Mermaid” always made me sad, but her self-sacrifice was at least ennobling.

I love the perspective of this article! I grew up hearing negative commentary on the morals of Disney’s Little Mermaid and grew to dislike it myself. However, this Christian perspective on Anderson’s story has changed my mind, not about the Disney version, but about the the values that exist in Anderson’s version of The Little Mermaid. It presents a realistic view of how life can be unfair while also providing hope to a bleak story.

Thank you for an intelligent analysis of Andersen’s story, and not another misinterpretation by a slavering Disnidiot. No one, it seems (least of all a millennial) seems willing to or even capable of appreciating the original story, that has enchanted people for generations, on its own terms.

I have to imagine I’m one of those millennial Disnidiots to which you refer, and I have deep appreciation for both the Disney adaptation and the original Anderson text. The two aren’t mutually exclusive in my eyes.

When you put it like that, it seems like a lot of the confusion about the story’s ending is simply a natural consequence of the disappearance of religion from our daily lives. For any religion to make sense, you have to understand how it operates and understands the world; if the religion teachers that an immortal soul is achievable and important, then any story based on that religion will stress the importance of an immortal soul as well. But you would have to know this about the religion to recognize it for what it is.

Actually, now that you mention it, this story could be considered a really interesting commentary on contemporary society. It seems most people nowadays accept that there is no God, and no immortal soul, and so they concern themselves with material affairs and their state of being on Earth. Whereas those who maintain their religion traditions–or want to become religious–are the only ones who bother to look for something beyond the material world anymore.

As a child I would spend hours reading fairy tales. The “happily ever” after being it’s main draw, of course. When I read the little mermaid, I remembered being so heart broken for her…I could not stop thinking of the tragic ending for days. When the disney version was release I was about 12 or 13 and I remembered being so happy at the happy ending they gave the story that it easily became my favorite. As a middle aged woman, after experiencing my own heart aches and going through my own spiritual and religious journey, I came to appreciate the original story’s ending. “All she wanted was a soul”. It was her happy ending, I just didn’t see it before. Thanks for his article Allie.

I see this as a didactic cautionary tale; extreme at points but in an odd way, realistic.

I just read the manga “Whale Star” which deals with independence, love, it’s also tragic. It tackles the story of the little mermaid as well. A modern twist. So I got curious and read what the ending of the little mermaid really is, it’s tragic as well. But here I find it happy rather than the manhwa. Just reading this article made me tear a little. Such good writers.

Fairy tales are cautionary stories. They are a safe place in which children can deal with difficult feelings that later they might experience in real life. It is sad that today’s adaptations of Fairy Tales are all too happy, that does not help our children to learn to think and solve problems or deal with the unexpected situations of life. I think Andersen’s ending, although influenced by catholic beliefs, is a good balance for this story.