The Importance of Learning the Classics

With the overwhelming amount of texts that are available in the modern world, from the local library to massive online vendors, it can often be daunting for people with an interest in writing or literature to know what is and isn’t worth reading. As a result, a debate has loomed as to whether or not it is important to read the “classics” of literature, or if a reader’s focus should be geared towards more contemporary works.

First of all, it is important that we have a solid understanding of what is meant by the term “classics.” The problem is that it is loosely defined, and there are almost as many definitions as there opinionated individuals. Historically, classics have referred to the works of classical civilization, namely the Greeks and the Romans, although the term is now widely used in a different sense.

It is important to distinguish the concept of the classic from the related concept of the literary canon. One way of understanding the difference is that the canon is a category of works currently considered worthy of reading, while the classics are the works that have remained significant to, and affected, subsequent generations. The canon is more strictly defined by a given generation, while the idea of the classics is more open, and allows for a more flexible definition, so long as the works have had an arguably large influence. These definitions are tricks, and they become even more so when we further divide the definition of classics into categories such as “classics of America literature,” “classics of European literature,” and so on.

While many people have argued that the classics are representative of a Eurocentric hegemony that conceals the oppressive nature of certain groups within society, the fact remains that the classic works of literature represent achievements of human thought in their scope, intelligence, and universality. We should also acknowledge that any work widely regarded as a classic has played a foundational role in the cultural and artistic climate of the present. While we should be aware of the exclusionary nature of any artistic tradition, we should also be able to recognize the value of the classics as they relate to all of humanity, and not just the groups that such works are ostensibly a product of. That said, generalizations are always risky, and what each of these books bring to the table, and the specific reasons for why they are considered classics is largely specific to the individual texts themselves.

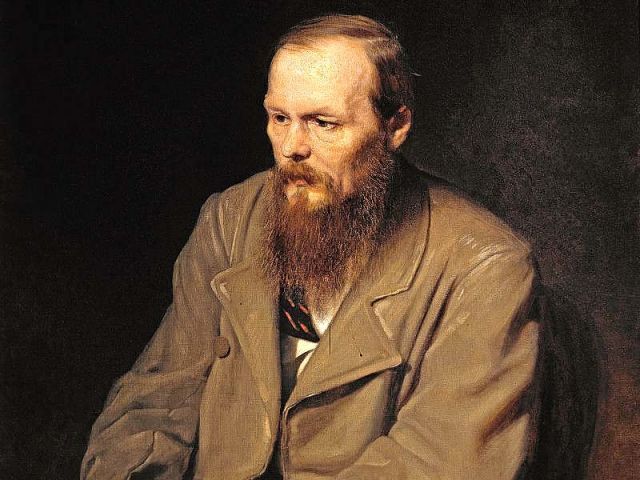

Take, for example, The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky. While the work is fiction, it is largely used as a means of exploring the philosophical tensions that were present in Russia, and indeed the world, in that time period. These examinations largely focus on problems of faith as confronted with the existence of evil, as well as the rising conflicts between faith and science. This, coupled with Dostoevsky’s deep sense of the psychological workings of his characters, and of the time period in which they are operating, makes The Brothers Karamazov a work that is simultaneously a well-written and entertaining story, a philosophical exploration into the major intellectual, philosophical, and religious dilemmas of the time (dilemmas that are largely universal to the human experience), as well as an accurate portrayal of Russian society in the 19th century.

All of these aspects of the book remain relevant to us today, for these debates are still ongoing, and the history implicit in the work shows us the development of the philosophical, intellectual, and historical climate we are currently inhabiting. The themes of The Brothers Karamazov, and those of other classic works, deal with human universals, such as how to structure value, how history develops, and how we interact with one another. The quality of such works are such that their contents still speak to us, despite the progression of time that leaves the majority of art seeming anachronistic and irrelevant.

This is merely one example of a book that is widely considered a classic, but it shows the underlying value of works that make it into this category. What constitutes a classic, then, is not a specific set of characteristics, but rather a text’s ability to be continuously relevant, and to provide seemingly unending levels of interpretation, meaning, and an examination of apparent truths that continue to speak to us through time. Classics are books that contain a scope unseen in other works of literature; they are books that remain universally relevant through time. Once we understand this about classics, the question then becomes what is to be gained from examining such works?

In the world today the idea that things progress as they move forward has become highly prevalent. This may be due to the trend of technology to improve as time goes on, but this does not mean that everything evolves in this manner. Such is the case with literature; it’s not always that newer works are better, and there are a massive amount of older texts that are widely thought of as masterpieces, and which have never been bested in their particular niche. These books are considered extremely significant, and often fall into the realm of genius. These are the books that become classics. While there are some who would argue that these labels are merely opinion, there are always specific reasons why they get applied to these books, and anyone who takes the time to really understand what makes such works significant would be hard pressed to say that their quality is merely subjective.

While the classics are monuments of achievement in literature, they also provide grounding in the historical development of writing, thought, and culture that permeate every text as a reflection of the period in which it was written. To read Dostoevsky is not merely to study the writer’s incredible style, storytelling ability, and character development, but also to witness the philosophy, sociology, and culture of an entire civilization as filtered through narrative. These things are some of the most worthwhile subjects to study, as they give us insight into our own cultural lineage, the entire intellectual debate of humanity, and the progression of history.

Therefore anyone who wishes to have a solid grasp on the intellectual history of civilization must read the classics, and this is doubly so for those with an interest in writing. In order to be able to create something even marginally original, it is imperative that one has a solid foundation of what has already been done. This is something like the cant of “learning the rules before you break them,” and although it may be impossible to read everything, any and all exploration into the great works of the past will provide massive amounts of insight into the landscape of style and content that already exists. Not only that, but any writer will benefit massively from encounters with what is possible within literature, and by stretching the mind to be able to understand such feats their own writing will begin to improve as a result.

In the classics we see the intermingling of all these forces, in addition to the revolutions of the technical style and form that such works also bring to the table, and every classic book has in some way changed not only what is being said, but how its being expressed. These two elements come together in classic works in a way that changes the way people think, and not just people in the past, but people living currently, as well. This is the meaning of an education, and literature, especially the classics, is an invaluable aspect of any thorough education.

The classics, then, are not valuable merely for the passive enjoyment of storytelling, but are in fact a doorway into the largest conversations that human beings have ever had; they are unique forms of expression, as well as a means of seeing into alternate realities that, although they are fictional, have something to teach us about ourselves and the nature of the world in which we live. Therefore it is not merely those interested in writing who have much to gain from the classics, but rather anyone who wants to widen their gaze and better understand civilization and what it means to be a human being.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

great one Greeks gave us our ideas of democracy and happiness

I am one who does enjoy reading the classics. At uni last year I did a course on them and it was one of my favourites. Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens are two of my favourite authors.

I find that reading the classics helps us to understand the past life, the social viewpoints, geographical context and cultural information of different time periods. There is so much information in the classics that teaches us about the past but that we can also put into our lives today, learning from past mistakes and ensuring they never happened again.

An excellent article.

Good article and I couldn’t agree with you more. The ‘Classics’ are still with us because they have withstood the test of time.

The only classics I recommend to casual readers are The Picture of Dorian Gray and Great Expectations.

Classic books were not written as classics. They were written as contemporary novels by people of the period for people of the period. To appreciate them fully you probably need to have read them when they were published

Exactly. They may have been masterpieces back when they came out, but the ravages of time are unforgiving. Today’s writing is simply superior.

Many of them weren’t even written as novels. Each chapter came out in a magazine each month.

They were designed to be readable and had to persuade people to buy the next edition. Something like Vanity Fair is actually eminently readable just as soap opera, as well as being something much more profound.

Why are classic novels labelled as ‘classics’? Because they’re good reads, of course.

Not always, remember Morrissey’s biography was published as Penguin Classic and, and although I like The Smiths and some of his solos very much, I would not go as far as call his life a classic. But then again, it might well be a good read for some…..

Maybe more because they are timeless and about being human, no matter what country one hails from. However, only if you like the author’s writing style will you consider a so-called classic a ‘good read,’ no matter how universal the themes are. For myself, there are several books that draw me because of the subject matter, but then I try reading them…

Love reading classics. I used to commute (by train) to work, so had time available, and it’s my main form of escapism.

For the longest time, I thought I was a sham of a literature student because classics are not my favourite. But they are an acquired taste, and one that is perhaps necessary, at least to gain insight into where literature has been and where it might go next. And there’s something reassuring about seeing generations of humans continuing to tell stories, if nothing else.

Interesting piece, its definitely valuable to have a degree of scrutiny when comparing texts across literary history. The classics are those rare texts that have survived over time to still hold considerable appeal and value within the culture. Like you discuss here, they are often conscious expanding and demand critical attention and praise.

interesting article. most people will find classic literature boring and hard to understand but to a few this is where the love of words and comprehension comes out.

A very sensitively written article about the value of classics. I think you have made your case while acknowledging there is value outside of the canon as well. I enjoyed it very much!

I read Dostoyevky’s ‘The Idiot’ purely to impress the girl I was seeing at the time. It was her favourite book and it was so worth it, both from a literary and a relationship experience. She turned out to be mad as a box of frogs but still….

I can imagine that with English evolving ever more rapidly future generations, except for enthusiasts, are going to find them ever more difficult to stick with. Does it matter though? Time moves forward and sticking to the past isn’t necessarily a good thing.

I didn’t start reading classics from a sense of duty, but because a film of Nicholas Nickleby made me realise that they are in fact entertainment – I headed straight off to the library and got started.

I came to the conclusion last year that I like the three Cs: crime, comedy and classics. The 19th century is the best century for literature in general and I occasionally pick up a classic and jump into it. In the last 15 months, this has included Madame Bovary and her Russian counterpart Anna bloody Karenina, both of whom were unlikable little madams.

The only problem with this is that these so-called classics are not fun to read at all.

Depends on the reader. Some of them (but by no means all) I found great fun to read.

Maybe different people have different ideas of “fun”?

The notion of “classics” is a bit limited. Why just the 19th Century? I have never really got on with 19th century literature. Most of the stuff I like was written from the 1920s to the 1950s. Why I don´t know because that includes things written in many different countries and several different languages, but something about the literature of the early to mid 20th century appeals to me while the 19th century doesn´t. I´d far rather read Faulkner or Borges or Bulgakov than read Charles Dickens or Jane Austen. Or I´d rather go further back and read Dante or Beowulf. But whenever people talk about “classics” it´s often only a certain type of classic that seemingly comes up.

I like the fact that they open up different worlds in a way that novels based on everyday modern life can’t; I have even managed Les Miserables in French (with a translation near at hand) and find it much more compelling in its own language.

The classics on the whole don’t do it for me.

Classics are fantastic. With my eyesight apt to deteriorate, so I was advised some 15 or so years ago, I decided to get started, while I could still see well enough, on books I wanted to read – and on visiting works of art I wanted to plant in my memory.

Those books are simply boring. Not as good as modern writing. It’s like film fans praising Citizen Kane. Yes, great accomplishment for its time, a paradigm change of orgasmic proportions, blablabla. But view through the lenses of modern film, it’s boring and unimaginative as fuck and visually atrocious.

Reading should be fun – as long as you’re reading something, there’s no point feeling dumb because you haven’t read Proust and only like reading ‘Fifty Shades of Grey’ (even though it’s appallingly badly written). The classics are classics because their relevance and writing has travelled well through time, but reading is not just about reading something classic – it’s about escaping to another world.

All I wish was that there were more Minecraft books available and Harry Potter goes to uni and the prequels when he was at kindergarten. New classics are what we need.

I’m completing a 19th century literature class at the moment, and I think the ‘classics’ are worth reading because they open a window into our past.

For example Prelude to Christopher by Eleanor Dark…published just after the WW2 and set at the beginning of the war time. Nigel was a believer in eugenics (before Hitler and the Holocaust cast a negative light on the theory) and trialed an experiment to create the ultimate colony, however his wife had a hereditary illness and he did not want to have children because they would be tainted.

Reading books set in historical time opens up the realities and politics of the era, so we can grow as humans and reflect on our past.

(btw…I’m saying saying I believe in eugenics.. it was an interesting novel to read!)

The definition of a classic, according to the author is something that has universal application and relevance. Works that stand the test of time, that teach meaningful truths with timeless appeal are one way that the past can communicate with the future. We will not maintain the advantage of progress if we neglect the understanding that brought it about.

Great article – well written; succinct, to the point and informative. However, some phrases bear closer examination: “The canon is more strictly defined by a given generation, while the idea of the classics is more open, and allows for a more flexible definition, so long as the works have had an arguably large influence.” – perhaps, could do with a greater clarity. This, along with some of the other claims made in the article, are really just opinion, rather than evidence-based or substantiated by empirical study.

For example, in defining “arguably large influence” the (educated) reader is left to wonder, firstly, why this is arguable? The term ‘arguably’ seems to be thrown about all to commonly these days as a way of ‘hedging one’s bets’ regarding a claim or supposition. Do not misunderstand my intent in this, I totally agree with the writer’s stated sentiment that the degree of cultural influence does indeed denote its status as a ‘classic text’ – nevertheless, apart from the later offered insights regarding Dostoevsky’s eponymous narrative, there is nothing to support the claim that this particular text has been as influential as the writer insists.

All, in all, though; I was entertained and engaged sufficiently to read the whole article, and this in itself is proof that the writing was of a high quality and that the argument made in the article was sufficiently supported and outlined.

I never really considered the differences between the literary canon and the “classics”, considering the terms synonymous. Interesting food for thought.

I like this article – especially the bit about how the classics are the greatest conversations that have taken place through history. Well done.

Thank you for this article. As a teacher candidate, I pushed learning the classics for a lot of the reasons you mentioned (I majored in and taught English). I still stand by those reasons, but wonder now how the canon of classics will evolve in the next 20-30 years or so. That is, will Harry Potter ever be considered universally relevant enough to make it onto generations’ reading lists? Will The Help become a cornerstone of the ever-evolving and ongoing civil rights conversation? It’s fascinating to think about.

A great discussion and an interesting topic to be considering. The issue of the ‘classics’ is one that remains highly debated in many literature departments the world over, with questions such as ‘does the list of classics change with perceptions of the era reading them?’ and ‘does the list continue to grow as time passes’. There are a number of debates that also raise issues related to the selection of the classics from a number of views: feminism, post-colonial and socio-cultural considerations. Is universality enough? I don’t think there will ever be a definitive list of ‘classics’ but I think in a manner this is part of the importance of continuing to engage in this debate.

My problem is, as you mentioned, the latent Eurocentrism behind the “classics”. Who gets to decide what constitutes a classic? And what gives that person, or body of people, the right?

At the same time, I honestly do see the merit in the classics you’ve mentioned. As I continue to further my studies, I’ve become more and more convinced that acknowledging the classics is important.

But, I am equally convinced that it is our responsibility to delve outside our own ethnographic perceptions of “classic”. Why not read the classics touted by a foreign, minority, philosophical, or pop culture? LGBT classics, Southeast Asian classics, feminist classics, African American classics, science fiction classics – the list goes on and on…

Perhaps the classics I’ve mentioned are not universally relevant. But by the standards of the cultures representative of those classics, I doubt the classics celebrated in Western academia are either.

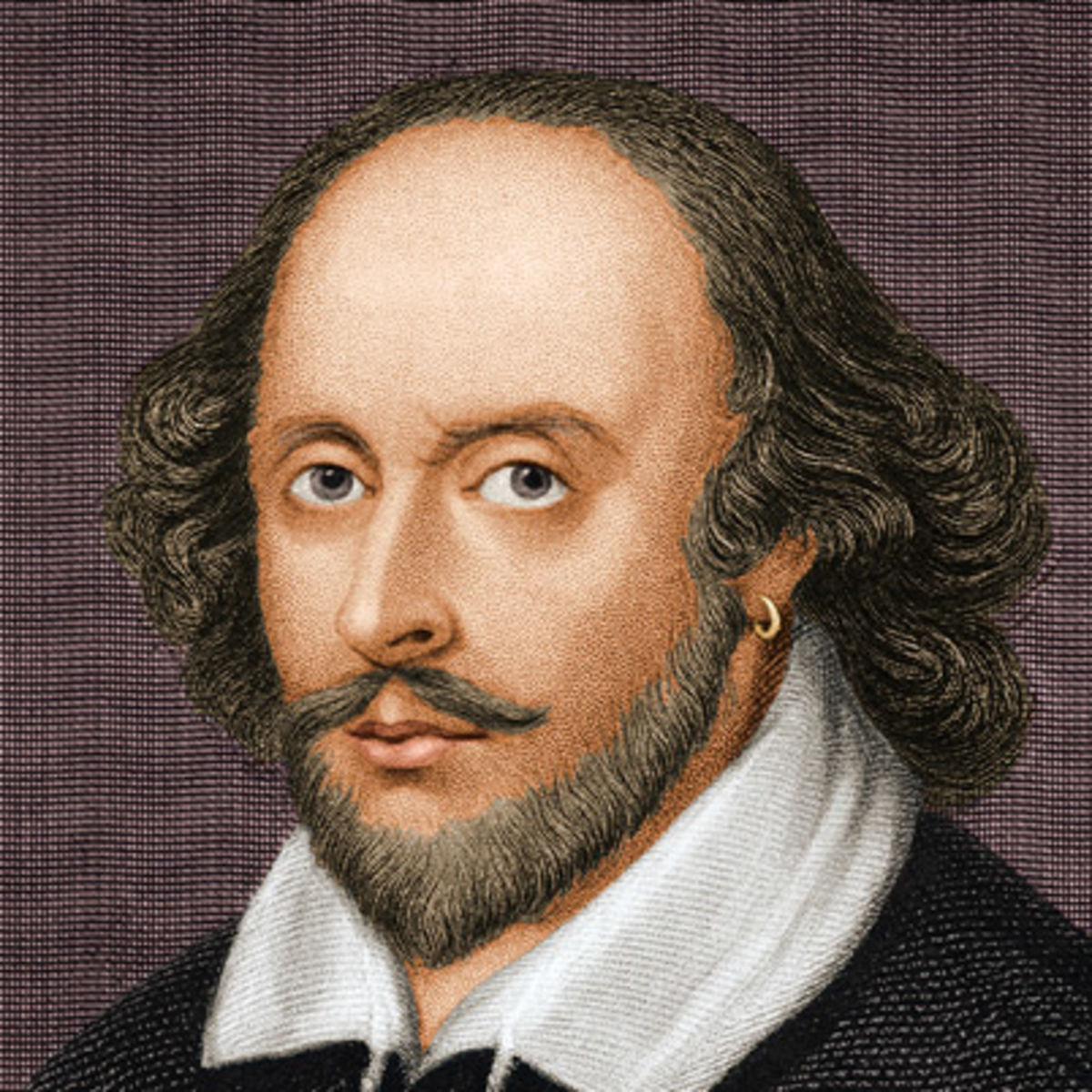

I personally really love the classics (at least the ones I’ve read so far). I’m in British Literature, where we study Shakespeare and honestly talking about his work on a daily basis has really gotten me to see how he, many other classic authors that we’ve studied, and their works are still extremely relevant even in 2017. With William Shakespeare, there are various interpretations of his works which makes them (among other classics) so enjoyable to read, watch and analyze.

I have discovered that in reading the classics I gain a better understanding of the topics at hand than I do via third-person analysis of the book itself.

Especially with regards to textbooks; there is more information per page than the condensed narrative the modern interpretation puts forth; one also misses out the wonderful use of language which the old-world cultivated.

Good article. Would have been even better with more specific examples. Also, you began to touch on it, but it would have been useful to tie in the the historical aspect with the idea of seeing the cliché of how the past is always close to the present. That is, books like 1984 are enduring classics because the themes of totalitarianism, propaganda, media-control, and more, are almost always relevant to the present.

Very interesting article that answered my own questions regarding the “classics”. In my schooldays those who were fortunate to study these works usually went to boarding schools and came from a different social class. However, reading is open to all classes and having been fortunate to attend a Jesuit school works such as Animal Farm, the short stories of Frank O’Connor, a few Shakespeare plays and Silas Mariner were taught. These became classics for me some forty years later. I continue to read these works simply for enjoyment and relevance as they are timeless. Intimidation no longer exists in my mind as I can appreciate them for the works they are and form my own opinion.

I couldn’t agree more. The classics are an important collection ever evolving culture throughout the ages. They act to spell out how culture has changed and why it is in the current state it is. Although reading Euro-centrist and western literature classics doesn’t give us profound inside into the inner workings of the many other diverse cultures in the world, they do help us understand the Western world as it is. Reading British literature classics such as Conrad or the likes may not explain early African culture but it can most certainly help readers to gain a more in depth understanding of our modern western world.

So many interesting questions could be raised from this article and many comments generated, as well…I, however, was immediately reminded of an instance in which I was teaching _The Canterbury Tales_ to my twelfth graders in a public school setting. I had just stepped in and taken over from another substitute teacher, and the students, having had several subs in a short period of time, were about done with school…and it was only October. My principal came in one day and told the students they simply needed to read it to graduate, that she hated it in high school, too, and that it made no sense to her back then, either. I was appalled! I explained to them, because they did not know, that Canterbury was a real place, as was Thomas a Becket a real historical figure. We did an in depth character study and compared the pilgrims to people we knew in real life. I explained how when we read difficult-to-understand texts, we need to learn to be resourceful. You don’t understand something? What do you do? Look at the footnotes provided, use a dictionary, Google it for crying out loud! Be resourceful. What happens when in a few years, you are choosing a health insurance policy filled with confusing jargon you’ve never seen before? I often urged them to practice reading a section of lines and moving into groups to break it apart and discuss what it meant. The practice of reading a text with difficult and “outdated” language – which many of the “classics” contain – helps us become better problem solvers, better critical thinkers, and teaches us to be resourceful. Though this is certainly not the only reason why I love reading and teaching these texts, it is one for which we need to argue, I think.

Great read!

Definitely see your point of view that every civilization has an established body of classics and that subtexts form their own particular brand of exclusivity and intrinsic importance in the interim. Like many people, I was exposed to the Greek epics and the British poets at a time when I was indifferent to their universal themes. Odd as it may seem, I find myself seeking guidance and purpose within those same pages and chapters as an adult.

Classics are important because they capture and preserve the histories of the era they were written in. Most of them also contain important predictions of the future that are usually quite accurate. I enjoy classics for their writing style because I find it generally more aesthetically pleasing and stimulating.

Good article, it sums it all up nicely – the classics offer so much more than the initial narrative, meditation or discourse could ever offer. Interesting too when you realise your ability to construct and also deconstruct abstract ideas improves so much from engaging and working with them seriously.

Throw in some Spinoza and Keirkegaard and you’ll be calm in the face of any chaos…

Cheers…

I think the classics work for the study of literature, because they’re often easier to analyse. As in, the basic but necessary skills of analysis (finding symbolism, locating clear themes of class, colonialism, love, female empowerment, applying historical context, etc.) are often obvious in classic literature.

Or at least that’s how I have experienced it. Good article!

A good essay.

I appreciate your defense of the term classic and what it implies. I feel sympathetically to keeping the designation ‘classics’ as a helpful signifier though I am also aware, as you state, of the cultural and historical baggage that it brings with it. Thank you for your contribution here.