Les Misérables in Film, Theatre, and Anime

This year marks the 30th Anniversary of the opening of the musical Les Misérables at the Barbicon Theatre in London. Since its premiere, it has gone on to surprise many of its original critics by becoming one of the most celebrated musicals of all time. As of October, 2015, it has been performed professionally over 51,000 times, been translated into 22 different languages, won over 105 major theatre awards including an Olivier, 8 Tonys, a Grammy, and 5 Helpmann Awards, made 47 recorded albums, and the school version is the most produced high school musical in the US, UK, and Australia. 1 This unprecedented success is due, in part, to the source material: the novel Les Misérables written by Victor Hugo and published in 1862. The success of the musical and film is also not surprising given the success of the novel.

This article explores the staying power of this famous novel through its own popularity as well as reincarnations in film and onstage. Ultimately the success of the novel is owed to the universality of the human condition embodied by the well-developed characters which Hugo created. While Hugo and the novel had very specific politics, outlined in the first section, the story of Jean Valjean’s redemption transcends politics and culture, as outlined in the second section. Meanwhile adaptations of the novel such as the 1935 American film version, the 1985 musical theatre adaptation 2, and the Japanese anime version, entitled Shōjo Cosette, have been appropriated for their audiences.

Hugo and the Human Condition

Given the international success of his novel and its descendants, Victor Hugo would have been proud of how many people have been touched by his story. After his book started to be translated and spread around the world, Hugo wrote to his Italian publisher saying:

“You are right, Sir, when you say that Les Misérables is written for a universal audience. I don’t know whether it will be read by everyone, but it is meant for everyone. It addresses England as well as Spain, Italy was well as France, Germany as well as Ireland, the republics that harbor slaves as well as empires that have serfs. Social problems go beyond frontiers. Humankind’s wounds… do not stop at the blue and red lines drawn on maps” 3

Hugo and his work were part of the Romanticism movement of the Nineteenth Century; a movement which is defined by Harvard professor Francis Fergusson as a genre in which “artist prophets” like Hugo expose the inconsistencies of the bourgeois culture which defined itself by rigid, close-minded thinking and social constraints. 4 To a Romantic like Hugo, titles which we use to define ourselves such as race, class, gender, nationality, etc. are illusions which distract us and hide our truer selves. This theme is evident in the fact that a criminal like Jean Valjean is not defined by who he is, but by what he does. Likewise, Fantine is defined by her motherly devotion and not her status as “whore.” This theme is also present in the fact that there is no place in Hugo’s world for Javert, who represents the bourgeois establishment and lives according to the codes of their absolutist, “reasonable” ideology.

Thus, Hugo’s radical novel, complete with personal memoirs, literary “red herrings,” ramblings on morality, contemporary tabloids, and a more detailed account of the Paris sewers than anyone asked for, was seen by many as a mirror reflecting mankind. 5 This view was even shared by those who disagreed fervently with Hugo’s politics.

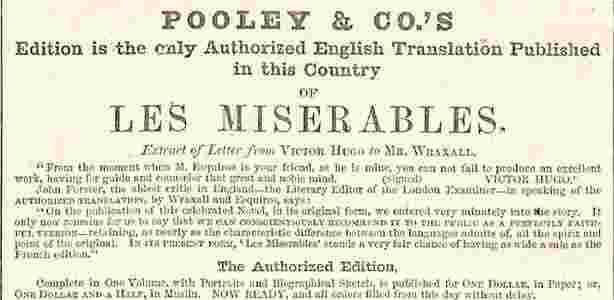

Lee’s Misérables

After the success of Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris (Hunchback of Notre Dame), his new novel Les Misérables was highly anticipated. Hugo helped fuel this anticipation by releasing a vague statement to the press from his publisher stating, “What Victor H. did for the Gothic world in Notre-Dame de Paris, he does for the modern world in Les Misérables.” 6 Posters were spread all over Paris featuring characters from the novel while people literally fought in the streets to get copies. While the book was criticized for everything from its sentimentality, to its “socialism” (even being banned by the Vatican), no negative review could stop the novel from becoming a populist juggernaut even in the most unlikely of places.

Because of Hugo’s strong anti-slavery stance, who would expect Les Misérables to become wildly popular in the American South, during the middle of the Civil War? Nevertheless, the novel made its way into Confederate bookstores as a Southern reviewer states:

“Indeed, for M. Hugo, the abolitionist, we entertain a sincere pity… He calls himself a philanthropist, he is warring, much after the manner of Don Quixote, for the regeneration of humanity; and believing that the negro is his brother.” 7

This statement reflects Hugo’s Romanticism and the way it was in conflict with more mainstream thinking in his day. However, despite this Southerner’s need to correct Hugo on his “ignorance,” this reviewer cannot help but love the novel; following this criticism of Hugo’s politics by asserting that,

“The picture of the workings of a mind [Jean Valjean], tossed between the Scylla and the Charibdys of Good and Evil, and painted in this part of the pages of Fantine stands alone and without parallel in modern literature. It is a grand and luminous vision of the interior of a noble soul-it is the core of a great heart revealed, turned inside out.” 8

I would argue that it was the Southerners’ own circumstance which made them understand misery in the way that Hugo’s characters do. One Confederate Soldier speaks to this notion in his account of the devastation which the South experienced towards the end of the Civil War when he writes:

“Everywhere, you might see the gaunt figures in their tattered jackets bending over the dingy pamphlets — Fantine, or Cosette, or Marius, or St. Denis, and the woes of Jean Valjean, the old galley-slave, found an echo in the hearts of these brave soldiers, immersed in the trenches and fettered by duty to their muskets or their cannon …. Thus, that history of ‘The Wretched,’ was the pabulum of the South in 1864… It was no longer the book, but themselves whom they referred to by that name. The old veterans of the army henceforth laughed at their miseries, and dubbed themselves grimly, ‘Lee’s Miserables!'” 9

Thus, long before any film or musical version emerged, Les Misérables had already captured the imagination of the world proving the Romantic ideal that even political differences are nothing compared to the shared human experience of suffering.

We Were Only Hungry

There have been many adaptations of Hugo’s masterpiece over the years beginning with his son’s attempt to make it into a play (which was banned) and several silent film versions. 10 Adaptations have appeared in times of war, peace, prosperity, and recession. Each new version makes its own cuts and changes, as well as its own impact on a target audience who will relate to the sufferings of the characters as the Confederate soldiers did. One of the more poignant film versions appeared in 1935 during the Great Depression.

This version, directed by Richard Boleslawski, opens with Valjean’s trial. In the novel, the trial is presented as a flashback, but the film chooses to start the events chronologically. Valjean’s courtroom monologue reflects the era of the New Deal more than the Romanticism of Hugo’s day, and is spoken in a colloquial American style as Valjean tries to reason with the judge:

“I didn’t mean to steal, Sir. What was I to do? There’s my sister and her family. I’m their sole support. There was no work, and no bread… You don’t know what it means to be hungry. You don’t know what it means to be out of work! I’ve tried and tried! I’ve walked twenty miles a day to find work. No work! No bread! I didn’t mean to steal. We were only hungry I tell ya!” 11

This Valjean is American in style and ideology. Valjean’s use of reason over emotional appeals speaks to the Protestant work-ethic values which are at the base of American morality. He does not care about the dismantling of bourgeois values, the freedom of mankind, or the battle of Good and Evil: he simply wants to work hard and feed his family. The undertones of passion and revolution are not present in this version because in the 1930’s, American leaned more towards social conservationism in the shadow of anti-Communist fears and the wake of the Great Depression, which had been blamed by some on the looseness of the 1920’s. However, even with the film’s deletion of Fantine’s entire prostitution plot-line, this film might be considered radical because of its advocacy for things like higher minimum wages in lines to Valjean as mayor praising him because, “Nobody pays better wages or looks after his work people like you do.” In this way, Hugo’s voice rings through all the sugar-gloss as slavery in the 20th Century is defined as economic oppression. In this version, one can see the ways in which Hugo’s work is adaptable to a changing world.

British Exports

The world of the 1980’s was a far cry from Hugo’s world (or at least Margaret Thatcher would have liked to think so). Many in the West saw their culture as a beacon of light and freedom compared to the oppressive Communist states. Nevertheless, the 1980’s was filled with, not just international tensions, but economic ones as well. It was not, however, the grumblings of the working class which made the musical theatre version of Les Misérables an international success. It was a combination of clever marketing, foreign investors, and the overall culture of British musical theatre in the Thatcher years which saw the iconic young Cossette logo seen all over the world.

One of the marketing tactics that became incorporated into musical theatre in the 1980’s was the use of logos. Musicals of the 80’s such as Cats, Phantom of the Opera, Miss Saigon, and Les Misérables often refereed to as “megamusicals” because of their size and grandeur, have recognizable posters. The images were standardized and mass-produced, much like the copies of a printed book. What these musicals have in common is that they are produced by Cameron Mackintosh who also perfected the art of using technology and resources to transplant musicals all around the world with the same standard as they had been produced in London. The exportation of British musicals of the 1980’s was only possible due to the fact that unlike British non-musical plays of the time, which focused on British identity and politics in a post-colonial world, the musicals of Andrew Lloyd Webber and the French duo who wrote Les Mis and Miss Saigon (Alain Boubil and Claude Michel Schönberg) were more universal.

Like the 1935 American film version, this musical made vast cuts and watered down Hugo’s politics into the Golden Rule and fights for “freedom.” However, by removing the politics and turning human misery into a catchy song, audience members around the world are allowed to identify with the characters even though they do not share the same kinds of extreme miseries which were common in the Nineteenth Century.

Shōjo Cosette

The universality of Les Misérables was tested, and triumphed, most of all in Japan: a culture which had little understanding of things like Nineteenth Century Romanticism or Christianity. Despite the cultural differences, not to mention performance style differences required for a Western musical, Japanese investors from the Toho Company saw potential and Les Misérables opened with much fanfare and the royal family in the audience.

It is not difficult to imagine the reasons that “Les Mis” as a novel and musical found a home in Japan. Daisaku Ikeda, a Japanese religious leader read the novel during WWII at a time when, like the Confederacy, the Japanese were suffering. He explains the reasons he was drawn to the novel, and later the musical: “While striking out at society which would give birth to such tragedy, he envisioned an ideal world where all people could coexist in peace.” 12 Here, Ikeda speaks once more to Hugo’s Romanticism and hints at the way in which, despite the simplification of Hugo’s work for the musical, the basic component still exists in the message: “To love another person is to see the face of God.”

Hugo’s style is consistent, in some ways, to Japanese styles of storytelling, particularly in Anime. The 2007 Anime Les Misérables: Shōjo Cosette, the fourth anime adaptation of Les Mis, is probably one of the closest adaptations to Hugo’s original novel than any other. Firstly, because the story is presented as a series, there is time in the 52 episode saga to include many episodes and characters that have been cut from film and stage such as Eponine’s sister Azelma. Because the series is geared towards children, certain darker aspects have been cut such as Fantine’s prostitution and Javert’s suicide. However, the order of storytelling, although not chronological, mirrors the novel more as does the emotional pacing and attention to detail. In the final episode, Valjean echoes Ikeda’s sentiments that the world is not perfect, but there is the potential for positive change.

In conclusion, the many, many adaptations of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables proves not only the universality of the novel but Hugo’s Romantic notion that we are all connected as human beings in our sufferings and our dream that “Even the darkest night will end and the sun will rise.” -Victor Hugo

Works Cited

- “Facts and Figures” Les Miserables (Official Website). Accessed October 13, 2015. ↩

- I have not included the 2012 film version in this study because many of the same principles of the stage musical apply to the film while the musical’s journey from stage to film could fill a whole other article. ↩

- Behr, Edward. The Complete Book of Les Misérables. New York: Arcade Publishing. (1989). pg. 39,42 ↩

- Fergusson, Francis. The Idea of Theatre: The Art of Drama in Changing Perspective. New York City: Doubleday & Co. INC. (1955). pg. 81 ↩

- Behr, 38. ↩

- ibid., 38. ↩

- Rosselet, Jeanne. “First Reactions to Les Misérables in the United States.” Modern Language Notes, Vol. 67, No. 1 (Jan., 1952). pg. 42. ↩

- ibid., 42. ↩

- Masur, Louis. “In Camp, Reading ‘Les Miserables’” New York Times (Blogs). Feb. 9, 2013. Web. Oct. 21, 2015. ↩

- Behr, 42 ↩

- Boleslawski, Richard. Les Misérables. 20th Century Pictures. (1935) ↩

- Young, Jin and Ikeda, Daisaku. Compassionate Light in Asia: A Dialogue. London: I.B. Taurus. (2013)., pg. 185. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I’m actually pretty ashamed to say that I haven’t actually read this and had no idea what it was about. Adding this to my list. It’s definitely a theme that can cross generations and culture.

Great article, I loved the combination of examining the original reactions to the book across cultures as well as how the story has grown and adapted. Anime is very hit or miss for me, but I may have to check this one out.

I like many others will have seen Les Misérables on many occasions and still remember my favourite and leave cheated every time the new one isn’t as good ( rose tinted spectacles maybe).

I like well adapted animes that follow their source work as much as it could.

I take my hat off to anybody who can write a profitable, long-running hit musical these days (whether I like it or not).

I don’t know why Hollywood loves to cast people outside their skill set so much. Why not cast real dancers in ballet movies and use real singers in musicals? As long as the sheeple are dumb enough to part with their money to see a “star” in a blockbuster, real singers and dancers will continue to be out of work, or reduced to “ghosting”.

As a singer, I found this article brilliantly insightful.

Les Mis is in a different class. It has heart, spectacle, great story and cracking tunes and you can’t ask for much more.

My wife and I first heard the audio version many years ago and could not wait to see the stage show. We were not disappointed and have returned to see it many times since.

I love the anime as soon as I started it! There were plenty of sad scenes which could pull my heartstrings and even make me cry and there were plenty of times where I feel happy for the characters. Great for anyone who enjoys adaptations of famous historical novels!

I think if a piece of literature is good, then it has the ability to transcend time and appear in other mediums as either a parody or adaptation.

Very true, considering Les Miserables themes of love and struggle can transcend multiple genres.

Thank you for sharing!

My wife and I saw the stage show many moons ago (at The Palace, Manchester) with no previous knowledge of it and it grabbed me immediately; I’ve loved the CD by the original West End cast ever since. Those minor keys just kill me every time.

Because of the anime, I decided to also read the original novel.

I saw that one which came out a few years back with three family members and all of us were checking our mobile phones to see how much longer there was to go, in my case after only thirty minutes.

I’ve never seen the stage version, but I have read the book, so I was unprepared for the disjointedness of the film as it left out many key story lines and incidents and ignored some of the connections between the characters. For example, that between Marius and the innkeeper whom he thought had saved his father’s life on the battlefield at Waterloo.

I felt no emotional connection with the characters and frankly, I found the film to be dull. The actor playing young boy shot in front of the barricade who later had a medal pinned on him should have got another one for being brave enough to appear in this turkey of a movie.

Les Mis (the Musical) is overrated. There – I said it. I totally love the anime though.

i saw the london stage production 20 years ago and thought it was the best, most moving musical i had ever seen.

That Les Miserables is a hit musical is a comment on the mediocrity of our times.

I love it. I love the fact it is earthy and guttural, just like the French peasants they represented.

When Eddie Redmayne (Marius) sang “Empty Chairs at Empty Table”, it made every stage performance I had seen of this hollow.

The audience i was with stood up to applaud at the end of the Anne H adaptation…this is the first time in my cinema going life that this collective act has ever happened to me.

At the sell out performance I attended, half a dozen people did applaud, the rest filed out silently.

I saw it in Florida on Christmas Day when it came out and everyone in the audience applauded. One cannot do that in the cinema especially if it hasn’t acquired one’s taste the one shall take one’s dramatic flight in the hope everyone is watching.

I really love the film, book, and play! I really love that the messages and symbolism is so applicable to life today, as well.

*are still so

I recently read Les Misérables in class and completely fell in love with it. I searched for Les Misérables anime and found this article. Thanks for writing it.

I have been privileged to see both the stage version and the new movie, both in their own way are magnificent and I thoroughly enjoyed them.

I felt the pacing in Les Misérables: Shoujo Cosette was somewhat tedious and the exaggerated happiness weakened the atmosphere.

I thought it was a great play – music, spectacle and story.

The recent film adaptation was bombastic, over the top and completely ridiculous in so many ways. But it was also absolutely bloody brilliant. We took my children – age 9 and 12 – to see it and they were utterly enthralled for the whole two and half hours.

My own favourite personal performance was in Oz! As a musical it still is the best I have ever seen. A one off maybe!

There have been many film adaptations too which have been interesting but none of them have been in the same league as this… take some time and watch them if you don’t believe me.

I love this anime so much. I have no idea how many times I cried and how many tissues I have used.

What a great article!

I love your article. There are many things you discuss that I had not noticed before. I am looking forward to reading more from you! 🙂

I’ll tell you why I walked out of Les Miserables. There were so many men in the cast and I couldn’t work out which one was Les.

Les Miserables has the Marmite effect on a lot of people, creating a division of those who love it and those who hate it.

The very first stage production in London was panned by the critics, but who cares about people who write things to get a reaction? The fact that it is a global sensation and has run in London for 27 years and still sells out says something.

It says that the critics were wrong yet again.

Shoujo Cosette is the perfect series. I have no doubts to put it on the top of the best I’ve seen. Everything fits well together, I’ve never seen/read the original Les Miserables but the Anime is very good maybe better than the original?

The anime accomplishes a connection to the characters which the novel doesn’t have. In the novel, Hugo presents the characters from a critical distance so that the reader will be able to see the full picture of a world in need of reform. Shoujo Cosette does more than establish pathos, it really finds the heart of the characters in a way that even the musical fails to do.

If you want to see ‘les miserables’ being done properly, you have to go and see it in the West End.

Interestingly, I saw it in the West End in 2012 and it was the best directed version I have ever seen. (This is coming from someone who has seen it several times, and assistant directed a local production). The original staging was still being used (none of this over-the-top unnecessary re-staging which happens on Broadway every couple of years and then closes). The West End version extracted things in that script and score which I had never even noticed. My one complaint was that I was able to see stage hands several times and see the “dead” bodies on the barricade get up and walk.

Because of the movie I decided to read the novel. I enjoyed the movie way more because I loved the music.

Great article on various adaptations I hadn’t heard about until now. The number of adaptations across different countries and types of media definitely asserts the Romantic ideal of universality.

I personally love the adaptations. I havent read the book yet, but now I will soon. The story overall can be seen and interpreted many different ways, and that’s what I like about it

I personally love the adaptations. I havent read the book yet, but now I will soon. The story overall can be seen and interpreted many different ways, and that’s what I like about it.

Very informative article. I like the section where you have discussed the mentalities and reception of the Southern states and slavery in relations to the book’s plot. Hugo’s book is one of favourites among fictions that presents a very much realistic picture of the 19th century France. While the 1850s “structural modernization” of Paris made the city as we know it today, it also excluded the many who lived in the poor quatres of France. Hugo’s book captures the true essence of the misery of the poor and the rise of French nationalism that led to the Revolution. Perhaps more dominant in the book are Hugo’s own political views, because of his involvement in the revolutionary movement.

It’s always interesting reading about controversies revolving around famous works. The political censoring and outright ban are evidence of the novel’s power.

Les Mis is one of my favourite stories and I really think it works well across multiple media (the novel, stage musical, and movie). It just has all the elements of a really good story.

One of the greatest works ever written. It is in my top ten included among Cervantes’ Don Quixote. When I saw the Broadway show as a little girl in the early nineties it was so beautiful I shivered. The moving Broadway production did justice to a work I thought could never come to life. Thank you for this article.

A good essay. I have seen Les Misérables probably some ten times in different stage productions. My daughters have always enjoyed when I took them to see it over the years.

“Thus, long before any film or musical version emerged, Les Misérables had already captured the imagination of the world proving the Romantic ideal that even political differences are nothing compared to the shared human experience of suffering.”

This seems to have been the general mindset among those that wanted to reunite the United States in the aftermath of the Civil War and informs why the political classes of the day made the decisions that they did.