The Role of Narrative: A Case for Diversification

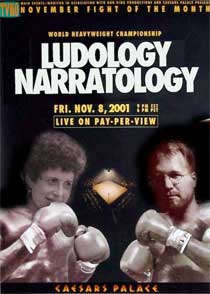

Around the late 1990s and early 2000s, the emerging field of game studies was split by aesthetic disagreements over how games should be understood. The two major schools of thought in this debate were ludology and narratology, and their constituent practitioners called ludologists and narratologists. Ludologists advocate the study of games on the basis of their abstract and formal systems of rules, divorced from their representative elements such as narrative, visuals, and sound. Conversely, narratologists advocate the understanding of games as a storytelling medium derived from humanity’s narrative tradition, and the application of literary and cultural theory to their study.

The ludology-narratology debate has died down in the past decade without any real conclusive answer, but the aesthetic influences of these two schools of thought are manifest in many contemporary games. Ludologists tend to study games of emergent narrative, while narratologists tend to study games of progression like Mario and Monkey Island while considering the conflicts between interactivity and authorial intent. While interesting from a pedagogical and theoretical perspective, binary approaches to studying and designing games are problematic and divisive, because they promote very constraining understandings of games.

The core tenet of ludology, coined by the influential theorist Gonzalo Frasca, is the assertion that “games cannot be understood using theories derived from narrative”. Academic ludologists search for new ways of “reading” game mechanics and relating them to a work’s overarching themes. Ludologists protest the creation of designer-dictated narratives and view the creation of emergent narrative as a facet of great design. Emergent narratives are unscripted stories that manifest out of a game’s rules, they may include dramatic character arcs in The Sims, and alternate histories created by Civilization V matches. To a ludologist, play and observation are intrinsically divorced; a game compromises its ludic nature when narrative is delivered through scripting rather than created through play. Ultimately, ludology represents a purist, if not formalist, perspective to understanding games, reading games independently of their representational elements such as graphics, sound design, characters, and narrative.

Ludology extends from a theoretical framework for studying games to a philosophy of game design. Most ludologists derive their practices from traditional games such as Chess and Dungeons and Dragons, designing mechanics first and considering the emergent behaviors that they tend to create. Narrative, world, and characters, when present, exist only as a window dressing to contextualize play and have little effect on the overall quality of a game. Ludologists tend to favor multiplayer games, open-ended simulations, or score-attack games. Examples might respectively include Street Fighter, SimCity, and Tetris. Ludologists view games as problematic platforms for storytelling as player participation in narrative fundamentally contradicts authorial intent. This is not to say that ludologists believe that games cannot achieve similar emotional aesthetics that traditional narratives can. For example, Monopoly was originally created as a protest game to teach players about real-estate exploitation by having players enact a story about wealth acquisition. Ludologists believe that representationally abstract games like Tetris and Super Hexagon are capable of creating emotions such as drama, tension, and catharsis through their mechanics alone.

Sid Meier’s Civilization games provide an ideal example of a ludologist-leaning approach to game narrative. Civilization is a competitive, multiplayer strategy game where players assume the role of great leaders from history, guiding their civilization from the prehistoric era to the far future. Players can achieve victory in a number of different ways, from achieving world domination, to winning a space-race, and wresting control over the United Nations. The game’s rules, which encompass everything from warfare to diplomacy, allow for an infinite number of alternate histories to emerge from Civilization matches. One match may see a warmongering player amass a nuclear arsenal to achieve world domination, while another may involve a player achieving diplomatic supremacy by controlling the world’s oil supply. Civilization thus acts as a framework to create dramatic emergent narrative, it achieves this by eliminating elements of traditional storytelling such as character, setting, and plot.

Narratology in games can be traced to Epsen Aarseth’s seminal 1997 book Cybertext; cybertexts were “texts that involve calculation in their production of [meaning]”. Video games are cybertexts because players author part of the narrative through play, thus game stories exist as an amalgam of player and designer-authored narratives. Henry Jenkins, professor of media studies at USC, views game design as a “narrative architecture” where players collaboratively enact spatial stories with the game’s systems. Games are uniquely poised for certain kinds of storytelling because they allow for the exploration of a 3D space, much like how the story-rich spaces of Disneyland attractions create both atmosphere and narrative. Many narratologists believe that interactivity does not necessarily contradict authorial intent, and that games are suitable for telling stories with variable outcomes.

From a design perspective, narratologists tend to favor single-player games of progression with cinematic, multi-act structures. Game designers that identify as narratologists tend to favor environmental storytelling, and interspersed cutscenes. Granted, the interactive nature of these games will lead to the collaborative authorship of narrative based on player’s choices within a game’s system. Theoretically, this would allow for players to hijack a game’s story with dissonant behavior, and thus narratologists implement measures to limit player-freedom. Players are prohibited by a game’s rules from performing actions that would disrupt the fixed-narrative. For example, shooting an allied soldier in Call of Duty immediately results in a game-over, allowing for the game to maintain its narrative focus.

A prime example of a narratologist-leaning game would be The Walking Dead. The Walking Dead is an adventure game where the player assumes the role of Lee, a survivor of a zombie apocalypse who meets the orphan Clementine, and is tasked with protecting her and leading a band of survivors to Savannah, Georgia to escape the country. Narrative interactivity in the game is limited to dialogue choices, and progression in the game amounts to rehearsing a series of predetermined actions to solve puzzles and advance the plot . The Walking Dead lives off the merit of its melodramatic and engaging narrative, which contextualizes the simplistic puzzles and imbues them with meaning, making the Walking Dead one of the most dramatically intense adventure-games of recent memory.

Both ideologies towards creating and studying games are problematic in their own way. Ludologist scholars like Markku Eskelinen hold that radically purist approaches to game design are the only legitimate approach, advocating the “[annihilation of] the discussion of computer games as stories, narratives, or cinema” . This radical approach to the medium upholds emergent, non-narrative game design as superior, and accuses narrative play of being inferior or illegitimate. That said, narratologists that ape cinema fail to use the unique perks of an interactive medium. One controversial example is Hideo Kojima’s Metal Gear Solid series, infamous for its excessive cutscenes and overwrought plot.

The most radical proponents of ludology, with their preoccupation over mechanics, fail to acknowledge the importance of other aspects of game design, such as sound, graphics, and worldbuilding. Furthermore, narrative contextualizes play and provides players with intrinsic motivation to continue playing. The act of defeating an enemy or solving a puzzle is imbued with greater meaning when it is contextualized with story. Furthermore, the success of games like Mass Effect and Bioshock indicates that there is a large market for narrative-heavy, single-player games with rich, extensive universes, showing that there is a diversity of reasons that people play games outside of purely mechanical sophistication. Radicals who call for the end of traditional storytelling in games threaten to commit aesthetic genocide, doing a great disservice to the medium.

Conversely, fringe narratology’s preoccupation over narrative fails to acknowledge the strengths of an interactive medium. When story and world are overemphasized, formulaic game design tends to follow, confusing the window-dressing for the window. Consider Japanese visual novels, which emphasize narrative to a fault, intermittently clicking to progress text becoming the core mechanic to progressing in these “games” . Furthermore, narrative’s need for art assets has the tendency to drive development costs to exorbitant heights, causing many big-budget games to fail to turn a profit. Mechanics have meaning and can convey ideas and emotions, just like narrative, consider the recent Thomas Was Alone, which characterized nondescript blocks through jumping ability. Making poor design decisions out of a preoccupation with storytelling can cause problematic phenomena such as genre confusion or ludonarrative dissonance, as seen in many of Rockstar’s open world games.

It is the intersection between ludology and narratology where the most interesting game design tends to take place. Game mechanics are imbued with meaning, and a narrative’s thematic content can be explored and reinforced through play. Yager’s 2012 military shooter, Spec Ops: The Line challenges the Frankfurt School’s theory that it is impossible for cultural works to authentically self-critique. Spec Ops is an indictment of video game violence and society’s attraction to violence in entertainment, accusing its own players of moral depravity for finding “fun” in a military shooter. While the narrative introduces these themes by having the protagonist suffer from psychotic hallucinations and hero delusions, the game’s mechanics reinforce its intended message. Spec Ops is deliberately poorly designed in order to raise questions about player motivation. The kills gradually become more brutal as players progress, raising questions about violence as a source of entertainment. These risky design decisions are realized at the game’s conclusion, when the protagonist’s subconscious breaks fourth wall and addresses the player directly, “you’re here because you wanted to feel like something you’re not: a hero”, tying up the game’s self-reflexive critique of violent games. The thematic depth of Spec Ops is the product of a balanced consideration of ludologist and narratologist views of game design, and ultimately, Spec Ops becomes a narrative that can only be told through an interactive medium.

Games are a rich medium entering a formal Renaissance, and their critical vocabulary remains at a formative stage. The conflicts between ludology and narratology that characterized game studies a decade ago have largely subsided, but the influence of that discussion is manifest as the medium continues to evolve as games try to break past those binary assertions. From the experimental proceduralist art-pieces of Jason Roherer to mainstream transmedia epics like Mass Effect, avoiding entrapment in binary ideologies while remaining open to their aesthetic merits allows for the greatest ludic diversity.

Extra Credits writer James Portnow predicted the arrival of a movement called Ludus Florentis, a flowering of games characterized by the breakdown of prior conceptions of what games were, and an expansion of what they could be. The movement, which arguably came into fruition in 2012, is characterized by an influx of games that both upheld and challenged the notions of ludology and narratology, and more people from all walks of life made games. From Anna Anthropy’s autobiographic Dys4ia to thatgamecompany’s deeply spiritual Journey, the collapse of prior conceptions of what games are has allowed for new genres to be discovered, new subject matter to be explored, games that speak to the human condition, games that exhibit underrepresented worldviews, and games that can better people’s lives. While this diversification might fracture the industry, aesthetically, it has kicked down the door to a wide-open future.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Holy smokes. I am a hardcore gamer but very new to game studies and had no knowledge of ANY of this. Thanks for the essay, very interesting!

I do not believe that narratology and ludology can be separated and pitted against each other. In order to have a truly successful and enjoyable game you need to have fun mechanics and a way for a player to become invested in the game.

exactly my point, its time to retire these debates and make the games that we want to make.

A truly informative and articulate article about some of the debates within game studies. This in many ways relates to some of some of the issues within cinema studies.

I do have to say, though, that I don’t think players can actually be authors of the video games or their narratives unless they are in some way involved in the creation of these games. I know that Jenkins gives a lot of artistic agency to users and audiences in general, but I would argue that he refers to the meta-text which moves toward a more abstract understanding of the idea of the work as opposed to the work itself.

I addressed this idea on my personal blog in an article about Bioshock, but basically, game stories are co-authored by game designers and players. Players are essentially actors in a story that a designer creates, and have power over the minute details in a narrative such as tactics, equipment, and exploration. I’m not that familiar with film studies and their formic controversies, do you have any suggestions on good essays to read?

http://kevinjameswong.com/2013/04/08/bioshock-infinite-is-a-metacommentary-on-the-nature-of-video-game-storytelling/

I see your point. Berys Gaut’s ‘A Philosophy of Cinematic Art’ has a useful discussion of cinematic authorship, and he extends it to digital cinema and interactive media. The chapter is titled ‘Cinematic Authorship’ and it specifically addresses videogames and audience interactivity. I don’t agree with much of his work as he rejects continental philosophy, but his discussion of authorship is logical and coherent.

He would probably argue that the power players have over “minute details” makes the games interactive, but because these minute details are created in advance by game designers and limited to what exists within the game, they are not co-authored by players.

His overarching argument, one that in many ways opposes the meta-textual work of Jenkins, is that one can only claim authorship if they activate a key production role and contribute to creation of the artistic properties of a work.

no major objections here, game designers implicitly author all possible narrative permutations of a game’s story.

Games offer a whole new angle on the phenomenological approach to narrative (cinema in particular), in that not only is every players experience different because of whatever they bring to the game psychologically and historically, but each player’s exploration of the medium itself can be vastly different, especially in some of these open world games. Even a game like The Last of Us, where the narrative is pre-determined, can permutate almost infinitely.

I don’t think is tone to retire the debate. This was week written by the way. I believe studying each individually and coming together in a synergistic fashion will make games better.

One aspect of my research is game mechanics that reinforce the narrative. Or mechanics that serve a different function ask together but makes the game have more meaning outside the screen.

Thinking in these two worlds on their own merits means deeper multifaceted multilayered games will emerge but that can only happen if each method is weighed against the other to provide balance.

I’ve studied narratology on my course but never associated it with games – and hadn’t heard a thing about ludology! Very interested read, thanks for going into this topic 🙂

Well said. Excellent article.

A very interesting read.

A fantastic and informative article, Kevin. Your knowledge and research into the subject is incredible. I can honestly say I’d never heard of ludology until now, but I’m happy I was introduced to it in such an enjoyable read!

I look forward to reading more articles in the future man!

Welp, I think that article’s just made it into my MA dissertation’s bibliography, damn fine work!

Jesus H. Christ, what an article. I love it. Thanks for the read!

That was an utterly fantastic read. Some of your insights are masterfully laid out and flawlessly followed up. Awesome.

Spec Ops was a very interesting case of how to imprint morality and choices upon the player, even when they didn’t want it! Great article.

Interesting essay, and the first I’ve seen that actually compare the two narrative classifications like this. Props to you for finally putting the two in a single article side-by-side like this.

I would like to mention that the mechanics of the “The Walking Dead” play largely into the narrative of the game. It’s easy to see how it incorporated narratology because of the substantial amount of text, but also discretely follows the ways of ludology as well. Though at first glance, mechanics seem completely unrelated to the game, think of moments in the game. Have you ever had to let anyone die? Was there a scene in which you desperately wished you could have done something else that could have been possible in a roaming environment, but due to the constraints of the mechanics, you felt hopeless and disempowered? I’d say the machanics are a significant portion of the storytelling in the game. Great article.

Thanks for the informative article. I love looking at gaming narratives, so I’m glad I now know new terms when looking at games.