Meditations of Modern Relationships in Film

Relevance Through Art

Modern relationships are often plagued with the menace of social media, the tabloids of cultural norm, the judgements of online strangers; or even things completely separate from the digital world such as death and loneliness — things that will continue to confound us through time. Relationships in the millennial “instagram-era” pave their own way for both satirical and fervently authentic portrayals of modern relationships through the medium of film, and in doing so are ever relevant to their viewers. These films, that will follow, have been selected for examination due to their philosophically, aesthetically, and culturally interesting content on the current state of human relations.

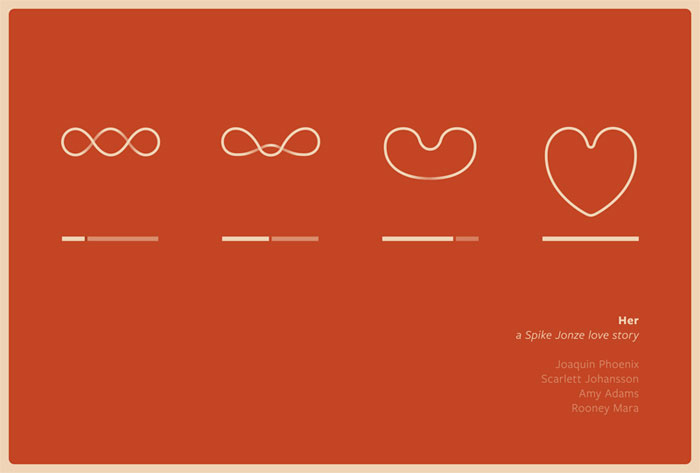

Her

Her is a meditation on love, loneliness, dread, and the socially handicapped society wrought from our increasingly disconnected milieu of technological comfortability. The film was met with adoration and hatred upon its trailer alone at the supposition that a person can or should fall in love with a ‘computer.’ This idea, however, is seated in the root of the film’s satirical look into our increasingly technological world. The narrative follows Theodor (Joaquin Phoenix), a writer who, in the final days of his divorce, falls in love with a new Operating System (Scarlett Johansson): a form of artificial intelligence designed to meet his every need. The two are easily drawn to each other due to Theodor’s reclusiveness with the world, and Samantha’s naivety entering into it.

The film centers around ideas of existentialism, deus ex machina, and the nature of identity and love; whereupon the film is not only about the state of human relations and their potential schisms, but the state of human Being itself. Much of these ideas are highly Baudrillardian: as one of the film’s primary motifs pits the nature of a human with a pixellated grey world in which to operate. This idea is developed through symbolic exchange and social movement by means of ascent and descent (told visually) throughout Jonze’s story. These narrative themes, however, are not encouraging the audience to go fall in love with their windows desktop, but the opposite: humans belong with humans, not technology. Theodor’s time spent with Samantha is not of authenticity, as Theodor may feel, but a simulation due to his isolation, anxiety, and fear of the world.

The film calls into question what the nature of human relations is, what it can be, and what problematic features of human existence come into question when in contact with things not of that same nature (such as a human and an artificial intelligence). The film is also an example of cinéma vérité, as Jonze uses the camera both poetically and non-poetically to break the barrier of social perception and human intimacy with the grandeur of the world and human individuality. The obscure nature of love and romance can be confusing, and albeit technology is ever increasing, ever evolving, perhaps Jonze would say our relationships should stay old-fashioned.

Restless

Gus Van Sant’s quirky romance story follows two youth in passionate and unstable love, by participating in a relationship with an expiration date. This film, unlike the others in the article, does not center around the idea of connectivity and socialization so much as the fact that people of the modern age are still heavily plagued with age-old things such as confusion, loneliness, and death – despite all the technological comfortability and medical advance of the modern world.

The film follows Annabel (Mia Wasikowska), a young terminally ill girl who falls in love with Enoch (Henry Hopper), a boy who likes to attend funerals and is friends with the ghost of a Japanese kamikaze pilot. The film explores the dynamics of Annabel and Enoch’s relationship, void of much social interaction, but full of internal grief. The nature of chaos in the world, despite modern technological advance, is what the film targets. The complex and often absurd nature of young relationships can be so questionable at an age already dictated by erratic behavior, that the nature of grief, anger, and even some self-loathing are what truly weigh on these characters–and these afflictions are all dealt with internally, not externally or socially.

Both Enoch and Annabel seem stuck in emotional turmoil over the cruel nature of life, the very nature of cruelty, and the profound effect it can have on us as humans. Van Sant portrays themes related to troubling bouts with disease, the problem of evil, suffering, and the strange relation between death and reason (Enoch’s imaginary friend being a vessel for this theme through pathetic fallacy) through the experiences of Enoch and Annabel alone, together: restlessly. Perhaps humans will always struggle with such plagues in such a way.

Men, Women, and Children

Discover how little you know, about the people you know. The tag line of the film reminds viewers that Jason Reitman is no stranger to examining the modern relationships of youth (as with his earlier film Juno), the latest installment in his subject of choice being Men, Women, and Children, a film designed to attack the potentially emotional and physical harm of social media on our romantic and platonic relationships as men, women, and children. Through a narrative that crosses the paths of many characters (thus satirizing the nature of social media as a means of separation rather than true connection), the film comes to assert that, like Her, people belong with people… That social media is but a distraction — a crowd — full of people too cowardly to be individuals.

Now, considering some of the extremely helpful things that social media can do, Reitman has his work cut out for him–but he takes it head-on. Reitman associates social media as destructive by the disgusting beauty standards that it can push onto young girls, how it can be used to exploit or bully young people, and how it can simply act as a catalyst for inter-family strife. Reitman interestingly pits all these negative facets of social media in the kind of light that starts to question whether their utility trumps their potential harm. The film’s ‘connected fate’ story is a narrative motif: showing how people affect each other lives outside of the digital world, that is, in brutal, emotionally charged, and often devastating way. Even one of the character’s mother’s attempts to stalk her daughter’s online history in order to “protect her” ends up pushing her further away, causing unforeseen tragedy to ensue.

These emotionally charged sub-plots also do a justice to their demographic’s struggle as well: many of the kids in the film suffer through coming-of-age things such as using social media to explore their sexuality, through intimacy and pornography. The characters often find it much easier to communicate with someone over chat or IM rather than face to face especially when asking questions like: what would you do to me if I was tied up?

While the film received poor acclaim, and there are undoubtably many problems with the film, its notions about the potential problems social media can cause on our personal lives is nonetheless important.

Knight of Cups

Terrence Malick’s “city-symphony” artfully depicts the essence of the “instagram-era” without its philistinism. The film has almost no linear narrative whatsoever, and the protagonist Rick (Christian Bale) never says anything unless in voice over, and even then his monologues are candid. Rick navigates his potential career and romantic interests through the playgrounds of Los Angeles and Las Vegas in search of himself through spectral experiences with modern bourgeois lifestyles.

Due to the film’s seeming lack of narrative substance, it’s simple to assume the film in fact, lacks. However, this style of cinema couldn’t be more relevant to the modern way in which people navigate society to ensue their social and/or personal desires. The film was disputed largely on the basis that it didn’t have any substance whatsoever, because it didn’t have a linear narrative whatsoever. In response to this, (1), the phenomenology of film rests in its ability to challenge the viewer’s mode(s) of perception–especially through something like narrative structure, and (2), even assuming a complete “lack” of narrative substance in the film would still prove noteworthy–with the latest trends being things such as Snapchat and Vine (both centered around the idea of popularity and intrigue through brief videos) there is a growing momentum of ‘moments’ that people use to sum up their lives through social media which Knight of Cups itself captures as a two-hour odyssey comprised of moments — which is in fact Malick’s poetic auteurship, but is also applicable to the modern age itself. The film is itself a compendium of moments that is together more meaningful than its parts — similar to human lives.

Knight of Cups is in many ways a spiritual journey: being widely regarded as an allegory for The Pilgrim’s Progress in Christian theology, but more importantly, is a portrayal of the way disillusionment has led people to obsess over image, ‘follower,’ popularity, and attention. This idea of getting famous or popular through a few seconds of something is what Malick exploits to instead show something artful and introspective. Rick experiences all these ‘moments’ that eventually equate to a vast nothingness in the hollow dreamscape of the city he traverses amidst an existential crisis. Perhaps Malick is saying this is what we all do, most of us without even thinking about it.

The Social Network

Arguably David Fincher’s most elegant film to date, The Social Network is a brilliant analysis of the single most potent strides in social networking ever: Facebook. While primarily about the legal and conceptual battles over the site, the film also looks into the interpersonal conflicts that fueled both the idea of the site itself, what its purpose was to be, and how it would go about its purpose. The film immediately takes the audience into the depths of Mark Zuckerberg’s (CEO of Facebook) social handicap(s) of, quite frankly, being an asshole. Whether accurately or not, the film paints Mark’s various social experiences with women and friends as negative and impulsive. These choices lead him to initially make a series of websites centered around the idea of social hierarchy/ranking and communication. Mark’s drive for this can be derived from his own personal desire for closer connections and experiences vicariously through online interaction.

In regards to Facebook, Mark’s final addition to the profiles includes adding a “relationship status” option because “this is what drives life [in college]: are you having sex or aren’t you?” This idea of associating sensitive aspects of social life — things that some might find uncomfortable to face in person or are simply not successful with — with the publicity through the online profile, is what the basis of Facebook (and undoubtedly other social networking sites as well) was. The Social Network makes it clear that Mark Zuckerberg and the other titan’s of programming and business marketing behind Facebook, while genius’, struggle with social interaction perhaps even more so than the average person.

The nature of online social networking seems to be paradoxical. It’s social exchange through profiles that can easily be veiled with careless and vanity-driven image. How can that be a beneficial way by which to become more connected with friends and the world? The Social Network is extremely relevant in understanding what the conception of Facebook was, and how many professional and personal relationships the creation of this site actually fractured or smeared, and how it still plays a role in doing that to everyday people today, and will continue to do.

The Lobster

Yorgos Lanthimos’ satire of human semblance is a mockery of society, elitist contemporaries, and the metaphysics of companionship/human relations. The film, being set in a near-future dystopia, is not so much an amusing idea of what can come with the future, but more so a stab at our state of modernity through this fantasy-esque portrayal through a not so far off from where we are right now positionality. The narrative centers around people at a hotel in the middle of the woods — a place you are sent if you are single to fall in love within 45 days, or else you’re turned into an animal and released into said woods.

The ‘system’ that runs the hotel is very much Lanthimos’ critique of contemporary society when it comes to sexuality (as each person has to either choose heterosexual or homosexual; bisexuality was considered errata with the latest corporate update), loneliness (hotel guests are ‘taught’ the merits of companionship through various methods of unusual physical punishment), and relationships themselves, as the character’s interests in each other is constantly called into question as to being true, or just pretend in order to leave the hotel.

Through the absurdity of the film and the strange obscure behavior of the characters, the audience is meant to ask what the very nature of companionship and love — no to mention individual identity — is. Lanthimos exposes the ridiculous and confusing aspects of Being with another person, committing to them, being faithful, and being happy, simultaneously.

The film harkens back to P.T. Anderson’s 2012 film The Master with it’s themes of man being nothing but a filthy animal, and questioning the potential meaning of any kind of human action/thought/feeling at a given time in ones life, and whether that action/thought/feeling can sustain its meaning over time. Moreover, with plenty of satirical black-comedy to both laugh at and think twice about, the quirky and often absurd nature of modern society’s rules regarding relationships and social constructs governing true happiness are ever present in Lanthimos’ film.

Louder Than Bombs

Joachim Trier’s intimate masterpiece Louder Than Bombs premiered at Cannes in 2015 and was nominated for it’s top prize the Palme d’OR; however, this recognition still seems insufficient of the grandeur and brilliance of the film. Trier’s examination of the fragmented lives of a family in turmoil, deceit, and self-loathing, transcends cinema through its themes of confusion, uncertain memory, and the nature of grief itself while navigating the complexity of adult life (and coming-of-age life). The narrative centers around the effects of a mother’s death (either accidental or suicidal) on her family and the family’s own personal lives.

The father and two sons struggle with the ties (or not) they had with their mother and how it begins to derail their own personal interests. The mother was a famous war-photographer who was rumored to be depressed, and because of this, a lot of controversy has be placed around the fact that the mother may have intentionally gotten herself in a car accident (it was rumored she was depressed–since she was away working so much, though no one really knew for sure). Like this complicated and controversial publicity, is the family dynamic. Both sons, one just having a child of his own, constantly butt-heads with the father who is (not to his liking) becoming more and more disconnected with them.

Throughout the film, the narrative fluxes through time, the audience never knows exactly what is present or past, what is truth or nightmare; the audience is, however, acutely aware of the suffering of the father and sons. Trier’s film transcends cinema, whereby using the medium (and particularly utilizing things like CGI–which is virtually unconventional for a narrative-driven family drama) to meditate upon the fact that (1) things like memory and grief plague our relationships with family the most, and (2) film itself interestingly portrays the nature of time and can utilize it to alter or distort its own reality, much like the characters do in the film.

The Past

The films of Farhadi tend to make all others look of artificiality, and his 2013 examination of guilt, punishment, commitment, and the ethical greyness of family strife proves this form. Farhadi’s films have an interesting tendency to feel like Dostoevsky novels; that is, they’re complex character studies of muddy narratives, opaque ethical transgressions, and — especially in The Past — turn out to be full of eye-widening mystery. Like many of his films, the validity of marriage as an institution is challenged, many characters are Christ-like, and are constantly pitted against the brutality and cruelty of the world in which they operate in.

Every second of the film is intricately woven to snowball the character’s past and present experiences into a mosaic of grief. The narrative follows Ahmad (Ali Mosaffa), a man who returns from his homeland to his wife and two children after deserting them when Marie (Bérénice Bejo/his wife) asks him for a divorce and becomes involved with a new man. Having to become accustomed to new parents and new siblings is difficult enough for the kids without the oldest daughter feeling the guilt of death in regard to Samir’s (Tahar Rahim/the new man) wife who recently attempted suicide — leaving her in a coma. The children’s angst of growing up and the stress and exhaustion of the parents creates a constant atmosphere of unrest.

The film is a complex work to say the least, and could easily take an entire article alone to analyze its examination of the human condition. The Past haunts us, and the last thirty seconds of the film will undoubtably haunt viewers long after the credits roll and the screen goes to black.

Nightcrawler

Dan Gilroy’s directorial debut Nightcrawler was masterful in its form and relevance in critiquing, uplifting, and invigorating audience members. The American information sector is unorthodox, to say the least. The corruption of major news providers, advertisement agencies, and what is deemed relevant corresponding to business enterprise, is disgraceful. It’s controversial, it’s misleading, and it’s engineered to appease the herd. However, in this chaos, one man can rise to power and success on his sheer will — his insatiable desire — to dominate his world by whatever means necessary. These means turn to be manipulating crime scenes and news stories to become more appealing to the hunger of the masses. This is Nightcrawler.

Almost the entire film takes place under the cloak of night — of darkness — both social and intimate. Louis Bloom (Jake Gyllenhaal) is a narcissistic sociopath who uses his creepy charisma to manipulate his world in his favor. Now, Gilroy doesn’t necessarily condone this illegal and morally barren behavior, but it’s starkly relevant to our modern time. The fascinating aspect of Louis, is that he could be anyone. What I mean by this is, he has no expertise in journalism, filmography, business, management… He’s somewhat of a random person, a mere operator in the world. However, he gains an insurmountable desire to conquer his world, and he does. Like the mighty Zarathustra!

Nightcrawler’s themes of violence and social anxiety can be extremely applicable to the state of classism, employment, the absurdism of social exchange, confusion, and of course, loneliness. Louis’s primary struggle to success is that he has to achieve that success by working with and associating with other people, whom he hates. This idea of loathing and isolation is a commentary perhaps on what social media is enforcing upon people today. Social media ordinates “haters” and isolation. While it’s more than rational to hate things worth hating, by “haters” I mean by definition to hate something on an unsound of invalid basis of knowledge. That is, hating something for an immature or unjustifiable way.

Other thematic material throughout the film include the iconoclasm of appearance atop reality. The epitome of this is Louis. Every time he speaks with another person he is in complete appearance, complete manipulation, complete facade by means of achieving his goals. This goes strongly against Kantian thinking and lines itself up more so with a brutal interpretation of Nietzsche’s will to power. Louis has concern for no one, and engages in obscure and disturbing behavior out of his psychic fragility.

Melancholia

Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia is perhaps, to this day, his magnum opus. Being visually masterful, psychologically perplexing, and disturbing as ever, Trier treads his favorable tropes while reaching for a new level of grandeur and depth in this character study and cinematic feast of a film. The narrative, engineered as a stream of consciousness, follows Justine (Kirsten Dunst) on the day of her wedding as everything turns sour, for no clear reason — while the planet Melancholia gets closer and closer to a collision with Earth. Justine’s happy wedding starts off with some normalcy, but by the time of the reception, Justine as abandoned the party and dwells out alone in the woods and her private room.

With the impending doom of the world, everything loses meaning. Justine looses the will to live, and thus further’s her family’s turmoil with the event (her sister Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg) tries to deal with Justine’s onset of severe depression). Trier himself has had to deal with severe depression — of which this film holds as its primary theme. Trier uses his signature visual style to distort time throughout the film, leaving the audience wonder what’s exactly happening, what has happened, and why everything seems so pointless. Many suggest that depression itself gives the sense of distorted time; and it seems Trier has had personal experience. The film puts into perspective many things, most importantly of which is the deterioration of human relations in the face of fear, the absurd, and depression. All these things pile up, suffer, and for what? Any purpose at all? Trier would likely say no. He makes many visual references to the painting Hunters In The Snow by artist Pieter Bruegel. The painting itself is a representation of the brutality of the world weighing down on insignificant human lives, despite their personal atrocities and hardships that will come out of it.

All this existential trauma and loss of the will circle around the cataclysm that is Justine’s depression. Depression is something extremely prevalent today with approximately 350 million people having the mental disorder, and it’s clearly been something Trier has struggled intensely with. Depression can seem like the end of the world to those who have it and those who simply don’t understand it. Trier doesn’t offer any solutions with the film, but brings into very artistic light the nature of these problems and the human condition; and what it then means to be meaningless.

Our Lonely Supreme

The purpose of these films is not to portray some form of quasi-reality as a means of vicarious catharsis for the audience, but to provide them with some kind of meaningful introspection that can elucidate the joy, the confusion, the perplexity, and the suffering of relationships and human understanding. Whether focused on the growing concerns of modern technology, or the timeless fear of death, these films take something worth-while away from their own portraits of the human condition.

With things to come such as the ethics of A.I. and advanced medical practices like cloning, the question of the phenomenology of human nature and being and has never been more prevalent, and these topics bleed into the concern of our personal relationships and human Being itself. Sometimes science can fail to go deep with the nature of these concerns; perhaps art is the form by which to seek out truth.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Some of these relationships and situations seem like a good idea on paper but not reality.

Thank you for writing this timely, significant article. Could you elaborate on how Jonze uses the camera “poetically and non-poetically” in her? Thanks in advance.

Two of my favorites: Last Tango in Paris and Y tu mama tambien.

Gus Van Sant probably understands the minds of youngsters better than any director around.

This is one of those perfect little films that glow in the heart.

I’m amazed that in discussions of the film Her, no one really doubts that Samantha is “conscious.” I haven’t even read one review that questioned that assumption. Nor does Theodore doubt this. This, of course, would be the central question that would obsess people should the world of “Her” come to pass. And trying to answer that question is a philosophical rabbit hole.

The movie doesn’t really play out a coherent vision of how society would react to an AI like Samantha. The bomb it would drop on culture and our vision of ourselves is too radical to even imagine, the social implications wildly unpredictable. But, that’s fine. Her was a meditation on love, connection and loss filtered through the prism of our current relationship with our digital devices. Watching the real world deal with these problems will be a far more dramatic movie, to say the least.

Love this movie, especially it’s vision at the end of the computers evolving beyond us into more perfect entities. Perhaps we will get left behind, as Theodore does. Perhaps the Rapture was for the computers…

Societally speaking, marriage has often been seen as a necessary rite of passage, but in Gone Girl, that assumption is turned on its head.

Most of Neil Labute’s films are built around messed up relationships.

Nurse Betty

In The Company of Men

Your Friends and Neighbors

The Shape of Things

With the exception of Your Friends and Neighbors, they’re pretty great films worth a watch, though the relationships are so messed up it’s kinda disturbing.

Do you think “Les amants réguliers” fit here?

Knight of Cups took me through some of the deepest human emotions.

Restless is one of the greatest movies ever made. It’s simple, but it’s complex. It’s confusing, yet it’s still subtle.

What about Afternoon Delight?

I was in my mid- twenties when the internet hit the ascendance so i’m old enough to evaluate the pre and post-internet age, and experienced first hand some of the down-side of it, and I think “Men, Women, and Children” does very well to point out these things in an honest and realistic way.

The film is a messy, chaotic mishmash of sub-plots that predictably fail to amalgamate into one overall, coherent plot.

Just finished watching Her. Beautiful. Many subtleties within the film that could be explored, and no doubt people are gonna talk about this one for some time to come.

If you haven’t yet seen it, you might enjoy the film Lars and the Real Girl. It’s a sensitive and thoughtful portrayal of the relationship questions you ask here. Also, if you haven’t yet read Sherry Turkle’s Alone Together, I highly recommend it. Both the first half of the book, which is on relating to robots as substitutes for humans, and the second half, on preferring digital social interactions to real world/real time encounters.

There are some gems on here!

There are some moments of real poignancy mixed into the heart-breaking narrative in Blue Valentine which should have been mentioned in this list.

Restless is unbelievably good. It’s honest. Not only about life, but about the moments in life that make it so special.

If I was to give you only one recommendation, I would suggest watching Blue Valentine . It finds beauty in its depiction of the flawed nature and frailties of the human condition.

Those are such good suggestions! especially Her.

Good article! Your meditation on these films definitely encourages the asking of more questions. Though, I have yet to watch most of the films you have listed, I feel drawn by the desire to stimulate some kind of introspective thinking. I know something so definitive as “the truth” is likely not something I can get in return, but I have a better idea of the kinds of questions I can ask myself when I watch!

The nature of contemporary relationships, and the idea that we all want something new and reject the idea of complacency is something to be endorsed.

I think that probably movies should show more “happy” marriages and/or relationships, per se. (you can call me a romantic sap, i won’t sulk). I mean, not judging or anything, but waaaaay too much adultery going on in the tv shows/movies, just breaks my poor little heart.

The movies were explained well and great choices.

Loved the insightful analyses of these films. Gonna add some of them to my watch list!

I personally liked many of these movies. I am a fan of the movies that leave you thinking long after it is over. I thought that Men, Women, and Children was very powerful and I liked that I just found out that the guy had a hand in Juno which is one of my favorite movies of all time.

What about something like Natural Born Killers or Love & a .45?

Wonderful analysis of Nightcrawler, though I do not believe that Gyllenhaal’s character’s isolation is a commentary or has any relation to the effects that social media has on people today.

Good choice of films! Very enlightening!

I think this is a very well thought out essay that really brings a light to romance and love.

Fabulous article. I am a poet and it gives me lots to think about as postmodernism swallows up every attempt at meaning or social comment, especially in Canadian poetry. The only thing missing was the dates of the films and where one can watch them online or on DVD. Thanks a bunch. I really enjoyed this.

Only seen a few of these, but now i’m definitely compelled to see the others and compare! Spot on with The Lobster and Social Network–very intrigued by Restless. Well done.

Her was an excellent movie! While I agree that one of it’s central themes was human connection and the lack there of, I think the movie was mostly about the concept of consciousness and its limitations. Movies like The Matrix, I Robot, Terminator and Her are all cinematic attempts at perfectly posing the philosophical question of the consciousness/existence of artificial intelligence. They all seem to have one similarity: consciousness in the hands of technology is a bad thing. Her depicts this but in a lighter way. Instead of killing off humans in an attempt to become the superior beings of the Earth, Her’s operating systems simply fall in love with humans only to break their hearts after becoming mentally advanced in a way humans can’t understand. Technology is an amazing thing but will it one day become too amazing?

I have personally studied and written about the movie Her! I find this to be a very unique and new idea of modern relationships because of how technologically advanced our society has become. The argument around this movie is if his relationship with Samantha is actually considered to be a relationship. For a relationship to be built a person self-identity and social identity. Is it possible that a computer can have its own self-identity or is it all pre-built in?

I completely agree with your analysis of the movie Her. This a perfect example of how the modern relationship can transform. It is roughly common that people fall in love with someone they’ve met on the internet. The significance in it is that a profile has to contain appealing qualities in order to be desired by others, so some lie thinking they will find someone online who will love them so much as this fake person that they will see past the lies once it comes time to reveal them. Today men and women alike can fall in love with someone they shouldn’t completely trust. Also a reply to @brittanieclark is that I feel this is a real relationship. The same way someone can be in a relationship and feel content with themselves, someone can feel the same way towards anyone or anything which is not always a preferred or “normal” relationship but something that is completely possible.

I’ll have to watch some of these!

While I’m not someone who strives to watch movies (due to my assumption that I can’t sit for two hours alone), I can watch them in manageable chunks alone on YouTube. This article has contributed to that conclusion. Thank you.

Her and The Social Network I think are the best examples in this article, but I think the lack of 500 Days of Summer and The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind are glaring omissions.

Very interesting article! I would probably add American Beauty, The Perks of Being a Wallflower and Silver Linings Playbook to the list –especially American Beauty’s portrayal of the relation between Ricky and Jane, developed through Ricky’s obsessive filming of her–, as they all portray love relationships in a very modern and disillusioned way. Her is also a very good example, in its investigation of an unusual and ‘one-sided’ relation. In regard to that, I also thought of Ex-machina, as in the film Caleb falls for Ava in the same way in which Theodore falls for Samantha in Her, namely despite knowing they are not real.

You offer great analyses of these films. The ever-transforming nature of relationships and how we perceive them will likely always be a relevant topic. I agree with your closing statement: “Sometimes science can fail to go deep with the nature of these concerns; perhaps art is the form by which to seek out truth.” As with these movies you’ve discussed, the narrative form can often explore the layered complexities and contradictions of human nature in a way that science alone may not be able to reach.

In terms of storyline quality, Her was a rather underrated film, but it’s also a tough film.