Neil Gaiman’s Three Ladies: Two Titles that Reconfigure the Triple Goddess Archetype

Neil Gaiman’s latest novel, The Ocean at the End of the Lane, introduces readers – or, rather, re-introduces readers – to a trio of magical women, the Hempstocks. Ocean is not the first time this triad have made an appearance in Gaiman’s work, but it is the first time they’ve been so fully developed as characters and had a chance to shine on the center stage. Through the use of archetypal imagery and themes, Gaiman’s works create a cohesive and consistent mythos across different media and individual stories that, while borrowing from sources both modern and classic, yet belongs exclusively to him. In Ocean, Gaiman continues to build his personal ontology, not by simply rehashing common archetypes, but instead by revisiting his personal expressions of such. The Hempstocks are not merely another version of the Maiden/Mother/Crone, just as his characters the Furies in Sandman: The Kindly Ones are not merely another version of the Erinyes from Greek myth. Rather, both sets of women are the same characters shown in a different light. Ocean and Sandman are not part of the same series or sequels that might commonly contain the same characters; the connection between them is their shared mythos in the form of Gaiman’s Three Ladies, no matter how divergent the Hempstocks may seem from the Furies.

Summary, The Ocean at the End of the Lane

In comparing the two triads, we will begin with a brief summary of The Ocean at the End of the Lane.

In comparing the two triads, we will begin with a brief summary of The Ocean at the End of the Lane.

An unnamed narrator returns to his childhood home for the occasion of a funeral and finds himself “accidentally” revisiting a nearby farmhouse he remembers from his childhood. Once there, he sits by the duck pond behind the farmhouse and sifts through memories from his youth. The first thing he remembers is that his friend Lettie called the pond an ocean, then the rest of the memories come back — a series of fateful and extraordinary events he had forgotten. When he was seven, a lodger in his family’s home committed suicide in the family vehicle, and in doing so, opened the way for an otherworldly entity to malignly influence the narrator’s world. The narrator recounts the story of the intrusion from the point of view of his seven-year-old self.

When the influence of the otherworldly presence begins to negatively influence both the seven-year-old narrator and the people in his area, he turns not to his own family for help, but to the Hempstocks, three women who live at the end of the lane he met when the abandoned vehicle was found with the lodger’s body. The Hempstocks – Gran (Old Mrs. Hempstock, the grandmother), Ginnie (New Mrs. Hempstock, the mother) and Lettie, who appears to be eleven – are not like the narrator’s family; they know things they should not be able to know and appear to have magical powers. He feels safe with them.

The Hempstocks treat the otherworldly presence as standard fare, easy to handle, and the narrator heads out with Lettie, who intends to bind the entity so it will no longer be able to influence the world. In the course of this adventure, the narrator makes a mistake which allows the entity to magically attach itself to him. This prevents the binding from working properly and allows the entity passage to the narrator’s world. It appears as his new nanny, Ursula Monkton, and amongst the narrator’s family only he knows that Ursula is really a monster.

After harrowing close calls caused by Ursula’s influence, the narrator and Lettie try again to bind Ursula back to her place of origin, but because of the narrator’s mistake in the first binding, there is a piece of the passage remaining in his heart, meaning Ursula can only return by killing the narrator. Lettie therefore summons beings the Hempstocks call the hunger birds, which will kill Ursula and – she believes – thus save the narrator. Though the hunger birds do kill Ursula, they also sense the piece of the passage in the narrator’s heart, and want to destroy it as well. When they attack the narrator, Lettie saves him by throwing her body over his, and the hunger birds savagely attack her to get to him. After Lettie’s Grandmother forces them to leave, she and Ginnie tell the narrator that Lettie is not dead, but is no longer exactly alive, either. Ginnie carries Lettie’s body into her ocean, which claims her and from which, the narrator is told, she will eventually return. Before Ginnie returns him home, she alters his memories, leaving him to believe that Lettie has moved to Australia.

As a mature adult, the narrator regains (temporarily) the knowledge that Lettie sacrificed herself so he could live. It is a heavy burden, but as he leaves the farm, it is clear to the reader that his memories are already fading. The Hempstock’s magic re-stitches memories, and he has once again lost full, conscious knowledge of the events.

The Hempstock’s Neo-Pagan Allusions

Throughout Ocean, Gaiman describes the Hempstock women with many of the attributes associated with the Maiden/Mother/Crone archetype popular in neo-paganism. This archetype was codified by Robert Graves in his 1948 book The White Goddess: A historical grammar of poetic myth and is referenced in dozens of modern neo-pagan books – or, more often, considered as common knowledge with no given citation. Most readers at all familiar with neo-paganism will see the Crone in Lettie’s Gran, the Mother in Ginnie, and of course, the Maiden in Lettie herself. It is useful, however, to briefly examine the details of these associations.

Old Mrs. Hempstock, Gran, is both the oldest and the most powerful of the three women. She is repeatedly shown as being able to use abilities the others do not have the skill or power to perform, and they look to her when making decisions. She is introduced to the reader with this description: “We stopped at a small barn where an old woman, much older than my parents, with long gray hair, like cobwebs, and a thin face, was standing beside a cow.” (Ocean 19) Not only does the physical description imply advanced age, but the use of the word “cobwebs” evokes both the lines of wrinkles and the spider, which is associated with the Crone (Walker 419). It is also worth noting that the cow is also a symbol of the Divine Feminine, such as with Hathor, an Egyptian goddess (Walker 368).

Another description of Gran is also telling. It comes after the narrator has fled his home because his father – acting under Ursula’s influence – has tried to drown him in the bathtub. After being cold, wet, shivering, and terrified, the narrator is in a warm bath in the Hempstock kitchen, drinking hot soup Gran has served him; she has retired to her rocking chair to knit and give him some measure of privacy. He says, “I felt safe. It was if the essence of grandmotherliness had been condensed into that one place, that one time” (Ocean 92). This is not merely the presence of another person after a bad fright, not merely a grandmother, but the grandmother – the “essence” of such. This expression of the most idealized, purest version of a human attribute is the primary quality of archetypes and deific figures (McLean 111).

“New” Mrs. Hempstock, or Ginnie, represents the Mother figure of the triad. Of the three, the Mother figure is most closely associated with earthly, physical concerns — the Maiden and Crone are closer to their respective liminals between life and death (though on opposite ends), but the Mother is centered in a position of tending to physical needs and practical concerns. The Mother embodies the essence of Creation, yes, but while the Maiden plays and the Crone looks to the great mysteries, the Mother tends to stomachs and makes sure her household is clothed. When the narrator wonders who called the police after the lodger’s body was found in the family vehicle, he assumes it was Ginnie; she is the only one he deems would concern herself with such mundane details.

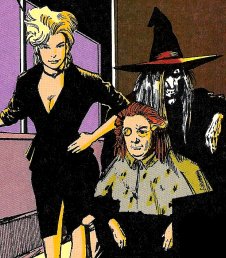

Ones, pt 1 (1).

Ginnie is described with “earthy” words: sensible, practical, firm, stout. The colors used in her descriptions are solid and earthy as well: green (her skirt and boots) and brown (her coat), like a tree. In the climatic attack with the hunger birds, when the narrator is hurt and scared and doesn’t yet know Lettie is gone, he clings to Ginnie for comfort against all the unexplainable, terrible things that have happened. “I held on to Ginnie Hempstock. She smelled like a farm and like a kitchen, like animals and like food. She smelled very real, and the realness was what I needed at that moment” (Ocean 160). A small child, he buries his face in her bosom, and she offers him the solace of her embrace, even though he is indirectly responsible for the loss of her daughter.

Most pointedly, in the narrator’s first description of Ginnie, he says, “I thought she was Lettie’s mother. She seemed like she was somebody’s mother” (Ocean 21). This is very close to the “essence of grandmotherliness” description used for Gran, and evokes the same idealized sense of a quality.

Lastly we have Lettie, the Maiden. Of her the reader gets the most description, as the narrator spends much of the story in her company. The neo-pagan Maiden is usually depicted as being just at the age of menses, slightly older than eleven-year-old Lettie, but given that the narrator is seven, that would have put her too old to befriend him, and their friendship is the heart of the book. Her apparent age is relatively inconsequential – while she has been eleven for “a very long time” (Ocean 87), she will always be the youngest and least experienced of the three. Indeed, her inexperience is a reoccurring issue. As an example, she makes the first attempt to bind the entity “Ursula” away from the world without knowing the entity’s true name. Later, when confronted again, Ursula openly mocks Lettie’s youth, saying “…you tried to bind me without knowing my name. Your mother wouldn’t have been that foolish. I’m not scared of you, little girl” (Ocean 118).

Because the narrator spends so much more time with Lettie, the descriptions of her are somewhat diffused – of all of them, she is the one he most identifies with as a person and not as a representation of her archetype. Still, there is an eloquent description of her early in the book that clearly evokes the neo-pagan Maiden:

Lettie Hempstock was standing at the bottom of the drive, beneath the chestnut trees. She looked as if she had been waiting for a hundred years and could wait for another hundred. She wore a white dress, but the light coming through the chestnut’s young spring leaves stained it to green (Ocean 29).

The quality of Lettie’s ancient youth is clear in this passage. That she could have been waiting a century only to wait a century more speaks to a sense of permanence and great age. But white is a color of the Maiden, as is the season of Spring (Farrar 35), and even the chestnut leaves are “young.” The green in this passage is not the deep, earthy green of Ginnie’s skirt, but one created by light pouring through new leaves, that yellow-green chartreuse of new beginnings.

The narrator – and therefore the reader as well – gets to see more of Lettie’s power than that of the older Hempstocks, and Lettie’s magic is the magic of children. During her first attempt to bind Ursula she sings in an ancient language, the language of shaping, but to the tune of a nursery rhyme the narrator knows, “Girls and Boys Come Out to Play.” She is also able, as the narrator is, to cut through the hedges and find secret paths. He says, “Children […] use back ways and hidden paths, while adults take roads and official paths. We went off the road, took a shortcut that Lettie knew that took us through some fields…” (Ocean 113). As a child, the world – life itself – is play to her. In one scene, she and the narrator are submerged in Lettie’s ocean, and while submerged, the narrator’s mind is opened to the secrets of the universe; he knows and understands both the physical and metaphysical underpinnings of reality. After the experience is over and he comes out of the water, he asks Lettie if that’s how she sees the world all the time; she says no.

“Be boring, knowing everything. […] It’s nothing special, knowing how things work. And you really do have to give it up if you want to play.”

“To play what?”

“This,” she said. She waved at the house and the sky and the impossible full moon and the skeins and shawls and clusters of bright stars (Ocean 146).

This is the Maiden’s gift: to see life and all it encompasses as joyful play rather than toil or hardship (Farrar 35).

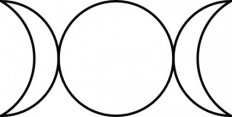

As important as the individual character traits are to the Maiden/Mother/Crone construction, it is equally important to the neo-pagan model that the archetype represents three faces of one woman in different life stages as much as it does three different women. Janet Farrar in The Witches’ Goddess writes, “…make the effort to grasp [the spectrum of the Maiden/Mother/Crone aspects], and you are face-to-face with the manifold Goddess herself. You are also face-to-face with Woman, the manifested feminine principle” (37). This three-in-one triad is represented in neo-pagan literature by the symbol of the moon in three phases: waxing crescent, full, and waning crescent. The waxing crescent symbolizes the Maiden, the full moon the Mother, and the waning crescent the Crone.

The Hempstocks display this fluidity of number as well, though it is a small detail near the end of the book. The narrator has explored his memories, spoken with Ginnie and Gran, mourned Lettie, and is leaving the farm. As he goes, his memories begin again to fade, and instead of seeing Ginnie and Gran together, he sees only one woman:

I said, “It’s funny. For a moment, I thought there were two of you. Isn’t that odd?”

“It’s just me,” said the old woman. “It’s only ever just me.”

“I know,” I said. “Of course it is” (Ocean 177).

Summary, Sandman: The Kindly Ones

It seems clear from these details that the Hempstock women are meant to represent the iconic Maiden/Mother/Crone archetype of neo-paganism. Let us now turn to another of Gaiman’s female trinities: the Furies as portrayed in Sandman: The Kindly Ones.

The Kindly Ones is the ninth collected volume of the Sandman comics, and features the climacteric point of the major plot of the entire seventy-five issue series: the death of the comic’s main protagonist, Dream of the Endless (also called Morpheus, and very occasionally, Sandman), at the hands of characters referred euphemistically as “the Kindly Ones.” Very early in the series, in the second volume, The Doll’s House, Lyta Hall is trapped in the Dreaming while she is pregnant. Dream eventually discovers Lyta and releases her back to the mortal world, but notes that it is rare for a child to gestate in the Dreaming, and says that one day he will come for the baby. During Lyta’s imprisonment, the ghost of her husband had been trapped with Lyta, but when she returns to the mortal world, Dream banishes the ghost, and Lyta blames Dream for killing him. Therefore, when Dream expresses interest in her son, Daniel, Lyta reacts with intense hostility. During the course of The Kindly Ones, a Trickster god kidnaps and kills infant Daniel, and leads Lyta to believe Dream is responsible. Lyta – already mentally unstable – becomes consumed with mad rage and seeks revenge.

Lyta’s quest for revenge takes her on a trip through multiple layers of reality. At the point she believes Dream is involved, her story splits into different perspectives. On one level, the material world, she appears as a delusional wanderer, speaking to stray cats and to her own reflection in store windows. In the realm of her subconscious, her reflection is shown as a separate being – two of them, actually, so Lyta is trebled on the page – and they each give advice. Meanwhile, in the mythic realm, she traverses nearly-impassable terrain and finally makes her bloody way to the goal of her quest, the Furies, who have the power to avenge Daniel’s death. These three expressions of Lyta’s reality take place simultaneously, with the narrative art switching back and forth, displaying in one panel Lyta’s mortal form, then her subconscious projections, and lastly her mythic reality as she meets the Furies.

When Lyta asks if they are the Furies she has been seeking, the Maiden says, “Not the Furies […] That’s such a nasty name. It’s one of the things they call women, to put us in our place. Vixen. Shrew. Bitch. […] Do we look furious to you?” (Kindly Ones, pt. 7 21) Lyta tells them Dream killed her husband, then her son, and she wants to destroy him. But they explain they cannot punish him for crimes done to Lyta: “…the Ladies you were talking about can really only avenge blood-debts. That’s one of the rules. It’s the oldest rule” (Kindly Ones, pt. 7 23). Lyta starts to leave, believing her quest has failed, but then the Ladies continue – the blood debt exists; Dream has killed his own son, Orpheus. That he did so to release Orpheus from an eternity of torment is inconsequential; family blood was spilled at Dream’s hand, that is enough for them to act. The Furies could not, apparently, take this action on their own — Orpheus was killed much earlier in the series – but once invoked they descend upon the Dream King and eventually cause his death.

The Ancient Roots of the Furies

The style of The Ocean at the End of the Lane is very close to magical realism – the world of the narrator seems very normal and grounded in mundane details, and the magic, when it occurs, also seems very normal to the characters. It is partly a function of the narrator’s young age, but even so, he takes the Hempstocks and their abilities in stride. Sandman: The Kindly Ones is more allegorical than realistic and plays out on a more mythic scale. The characters depicted are drawn more directly from ancient sources, and unlike the Hempstocks, can be understood as representations of specific, named, mythological characters. The Trickster who kidnaps and kills Lyta’s son Daniel, for example, is revealed to be Loki, from Norse legend. The main protagonist of the series, Dream of the Endless, is known within the series canon to have been worshipped by the Greeks as Morpheus, god of dreams, and is frequently referred to by that name. The Endless as a whole are allegorical representations of eternal forces: Destiny, Death, Dream, Destruction, Despair, Desire, and Delirium.

(McLean 31).

The three Furies of historical myth – Alecto, Tisiphone, and Megaera – changed over time in the way they were portrayed as the prevailing political winds of ancient Greece changed (McLean 31). Originally their purpose was to avenge the spilling of familial blood, especially in the case of a child killing its mother, but during the course of Aeschylus’s play “The Eumenides,” they are diverted from this role, appeased with a shrine in Athens, and re-named the Eumienides, or “kindly ones,” which was in turn a reference to an older triad of Earth goddesses (McLean 30-31). As D.J. Conway further explains in her book Maiden, Mother, Crone: The Myth and Reality of the Triple Goddess, “The Greeks called them by the name Eumenides (the Kindly Ones) because they were afraid to use their other name; this new superimposed image did not, however, change their stinging and avenging fury” (108). This bizarre conflation of avenging Furies re-dressed as “kindly” goddesses is the nature of the three mythic beings Lyta Hall supplicates for revenge.

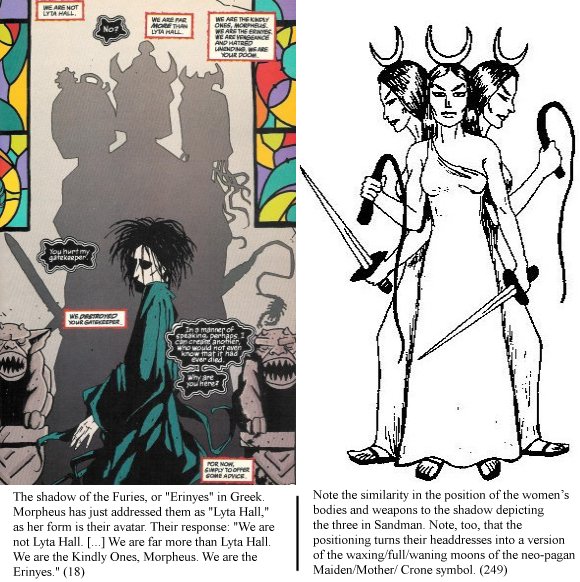

The Kindly Ones in Sandman, like the Hempstocks, also regularly shift in identity from one being to three and back again. When Lyta is successful in invoking the Three to pursue Dream she becomes their avatar; she is seen by others as herself (though in mythic form, as shown in the illustration above) but she casts a triple shadow and speaks with their unified voice. This is the image of her/their shadow, as depicted in The Kindly Ones, pt. 8, and a comparison drawing of the Furies as shown in The Woman’s Dictionary of Symbols and Sacred Objects by Barbara G. Walker:

Breaking the Mold

It seems clear then, that Gaiman intends to evoke related but distinctly different mythologies with his presentation of the Hempstock women in Ocean and the Furies in Kindly Ones, one triad truly kindly, the other only euphemistically so. However, as much as the characters reference or evoke mythological root forms, they are more than re-purposed legends, they are Gaiman’s unique creations. Details large and small combine to establish this, despite the strong resemblance to their respective source material.

For an example of a small detail that differentiate the Hempstocks from the Maiden/Mother/Crone archetype, we can note that the neo-pagan model very consistently states that the colors associated with the three are, respectively, white, red, and black (Farrar 35-36). The color white corresponds to the Maiden because it is a symbol for innocence and purity; the color red symbolizes the Mother because it is the red of menstrual blood and creation; the color black is for the Crone due to its association with death and the dark phase of the moon. These are not, however, the colors used to describe the Hempstocks. The only colors ever attributed to Gran are grey and silver, and the color red is never used in detailing Ginnie’s clothing or person. Lettie’s descriptions, though, refer to her in red clothing, not only white – in her first appearance she is wearing a red skirt, and later is dressed in a red overcoat (Ocean 19; 86). Moreover, when the narrator sneaks out of his house in the night to escape to the Hempstock farm for protection, he also wears red, in the form of shiny nylon pajamas (Ocean 74). Gaiman is using the color red for childhood, probably to capture the sense of passion and urgency in youth, but that does not fit the neo-pagan mold for the Maiden/Mother/Crone figure.

to Rose Walker

(Sandman: The Doll’s House, pt 1 19).

Additionally, and more vitally, despite their great power, the Hempstocks are very much people, and act as people do, not as unchanging expressions of their function. Immediately after Lettie’s death, Ginnie takes the narrator home and when he asks to stay with the Hempstocks and work on their farm, she says, “No. […] You get on with your own life. Lettie gave it to you. You just have to grow up and try to be worth it” (Ocean 167). This is a harsh thing to say to a seven-year-old, particularly coming from such an iconic Mother figure… but Ginnie is grieving the loss of her daughter and speaks, perhaps, more cruelly than she means to. It is a very human moment for a seemingly all-knowing, otherwise nurturing character. And indeed, when the narrator returns to the Hempstocks in his forties, Ginnie’s mood has changed. He realizes that Lettie – gone, but still present in her ocean – has been examining him while he remembered the events leading up to her death. He asks Ginnie if he has “passed” Lettie’s examination, meaning that he wants to know if his life has been worth the sacrifice she made for it. Ginnie answers, “You don’t pass or fail at being a person, dear” (Ocean 175). This is a much kinder response; she has healed, she has changed.

The changes are not restricted to mere shifts of mood, either. It is impossible to ignore a central fact of the story: Lettie died. She is not, perhaps, permanently dead, but that is not a known quantity. Gran insists that she isn’t, saying a Hempstock would never do anything so “common,” and adding later, “She’s not dead. You didn’t kill her, nor did the hunger birds […] She’s been given to her ocean. One day, in its own time, the ocean will give her back” (Ocean 164). We can probably trust Gran to be right, but Ginnie reveals she isn’t so certain. “The ocean has taken her. Honestly, I don’t know if it will ever give her back” (Ocean 166). If the characters were “merely” reflections of the human condition, then Lettie’s return would be a certainty – there are always new youths, new Maidens. She could not be destroyed. Yet still Ginnie mourns and reveals a very human sense of doubt in the future.

The Furies of The Kindly Ones also stray from their classic model, first and foremost because they do not adhere strictly enough to the narrow version of their source material, despite overtly naming themselves as such. In their every occurrence over the course of the Sandman series, they are always drawn as having the distinct ages of Maiden, Mother, and Crone… but the Erinyes did not have that aspect in classic Greek myth; they were of the same age, whether described as Gorgon-like hags or winged huntresses. (McLean 30)

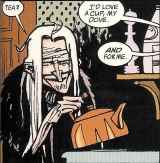

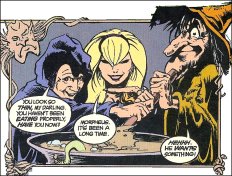

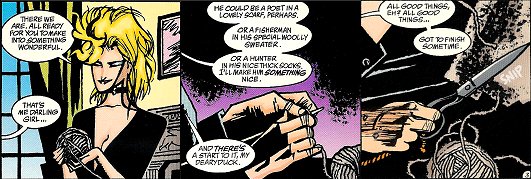

Additionally, when the Three are first shown in The Kindly Ones, they are engaged in an act usually attributed to the Fates: the Maiden character has created a ball of yarn at the story’s beginning, which she hands to the Mother, who – based on their coded conversation – knits it into a life for someone. Before the Mother feels it’s finished, the Crone snips the thread with a pair of scissors and says the other two are always too soft (Kindly Ones pt. 1, 3). This is the classic metaphor for Clotho (spinner), Lachesis (apportioner), and Atropos (inevitable) – but in Greek mythology the Fates were not the Furies, and vice versa (McLean 33). Gaiman has conflated the two, quite deliberately, and then cast them in the forms of the Maiden/Mother/Crone, contrary to classic myth, but consistent to how they are depicted throughout the body of his work.

(Sandman: Dream Country, “Calliope” 9).

Gaiman’s Mythos

Thus we see both the Hempstocks and the Furies are not merely Gaiman’s attempt to parrot mythic forms, but to re-invent and re-purpose them into new characters. Moreover, while disparate on the surface, the Hempstocks from Ocean and the Furies in Sandman can further be said to be expressions of the same characters, and are used by Gaiman to the same purposes in both stories. As Tess Malone writes in her blog review of Ocean,

If any contemporary author is an authority on the power and persuasion of myth, it’s Gaiman. The man has made a career of excavating myth and restitching it for his own art. His influences are clear, but because myth is such a primal interest, we accept and relish his evident borrowing. Now, Gaiman is borrowing from himself.

Gaiman has said that the Hempstocks first took root in his imagination when he was nine years old, and they have made appearances in other books: a Liza Hempstock, one of three witches, is a character in The Graveyard Book; a Daisy Hempstock graces the pages of Stardust (Schnelbach). But before Ocean, Stardust, or The Graveyard Book, there was the comic series Sandman, Gaiman’s first major success. The first run of Sandman under Gaiman’s hand spanned nearly ten years of steady publication. In the first issue of the series, Dream of the Endless is captured and held prisoner for seventy years. In the second issue, he returns home weak, nearly powerless, and missing his magical tools of office. In order to find them, he uses what little strength he has to summon “the Three-in-One,” in the hopes that she/they can provide information on his missing items of power. This marks the first appearance of Gaiman’s Three Ladies in his mainstream work.

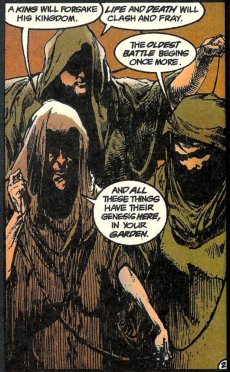

In the course of the next six pages, Dream refers to the Three-in-One by many different names. The servant who suggests summoning them specifically names “Urth, Verthandi, and Skuld” as those to be invoked; these are the Norns from Norse-Germanic mythology, and their names mean Past, Present, and Future, respectively (Conway 112-113). The Norns were also known as the Weird Sisters, which is another of the names Dream uses when addressing them. It is assumed by current scholars that the Norns are “quite likely direct descendants of the Greek Moerae or Fates” (Conway 113) and indeed, Dream greets the Crone by the name Atropos, even though he pointedly summoned them as Urth, Verthandi, and Skuld. The Crone’s response informs the rest of their appearances over the ten year run of the series: “Atropos? No. Not now. You might as well call me the Morrigan!” The Mother figure adds, “She’s right, my ducks. Might as well call us Tisiphone, Alecto, and Magaera…” (Preludes & Nocturnes, “Imperfect Hosts” 19). The Morrigan is an iconic triple goddess figure of Celtic/Gaelic myth, and, of course, Tisiphone, Alecto, and Magaera are the proper names of the Furies. The Three are saying that they could be those beings, but “Not now.” In their next appearance in Sandman, in the second volume of the series, The Doll’s House, they appear to a different character (Rose Walker; see illustration above), who asks who they are, and the Maiden gives this response: “Names, names, names… each name is but a single aspect of the whole. Be satisfied with the trinity you have. F’r example, you wouldn’t want to meet us as the Kindly Ones.” (pt. 1 19)

This idea – that the Three are the embodiment of all triple goddesses, from all cultures – is reinforced again when Lyta Hall finally makes her way to them and asks if they are the Furies, if she has achieved her goal and found them. The following exchange takes place.

Maiden: Are we the Furies?

Crone: Are you a hand? Or an eye? Or a tooth?

Lyta: No, of course not. I am myself. But I have those things within me.

Mother: There you go, then, my little scorpion-flail… (Kindly Ones, pt. 7 20)

Thus we see that Gaiman has distilled the Three Ladies into an archetype-of-archetypes, a meta-myth expression of a Platonic ideal, a character who operates on the grandest of scales.

(Sandman: Season of Mists, “Episode 0” 2).

This macro view of archetype is specific and consistent in Gaiman’s work, though admittedly not constant. (See American Gods for an example of a work where one Odin does not necessarily equal all Odins, let alone all Trickster or Death gods.) But we also see this grand scale expressed in the character Dream, who steps beyond the role of mere “Morpheus” – a Greek deity – to also be “Kai’ckul” to the First People ten thousand years earlier, as described in Sandman: The Doll’s House, “Prologue.” Indeed, Dream steps beyond not only the bounds of culture and time, but even species: in Sandman: Preludes & Nocturnes, “Passengers,” he visits J’onn J’onzz – a literal Martian from Mars – and J’onn greets him as Lord L’Zoril, who is known to the Martian people (15). Dream is clearly not bound by a concept as limited as “humanity,” and neither are the Three.

Gaiman’s Three Ladies – no matter their names or precise appearance at any given moment – are grand powers on the author’s mythic stage as much as are The Endless, especially within the boundaries of their sphere of influence. In Sandman, this is represented by the fact that they are able to threaten Dream in his throne room and eventually kill him – even though he is one of the Endless – and his sister Death is bound to do her duty. Similarly, in Ocean, the reader is told that Gran has been witness to the Big Bang – her scale is definitely “macro.” And when she threatens to un-make the hunger birds as though they had never been, they take that threat very seriously. Angered by the attack on Lettie, “Old Mrs. Hempstock” foregoes her usual appearance as an elderly woman and appears in the full raiment of her power. The narrator describes her aspect as too overwhelming for his senses to hold.

I knew who was talking. The voice sounded like Lettie’s gran, like Old Mrs. Hempstock. Like her, I knew, and yet so unlike. If Old Mrs. Hempstock had been an empress, she might have talked like that, her voice more stilted and formal and yet more musical than the old-lady voice I knew. […]

She shone silver. Her hair was still long, still white, but now she stood as tall and as straight as a teenager. My eyes had become too used to the darkness, and I could not look at her face to see if it was the face I was familiar with: it was too bright. Magnesium-flare bright. Fireworks Night bright. Midday-sun-reflecting-off-a-silver-coin bright.

I looked at her for as long as I could bear to look, and then I turned my head, screwing my eyes tightly shut, unable to see anything but a pulsating afterimage (Ocean 158-159).

Note the use of the word “empress” in the description. In the conversation Dream has when he invokes the Norns during Preludes & Nocturnes, he once addresses them as “Witch Queen” (Preludes & Nocturnes, “Imperfect Hosts” 20). The Three – both sets – are mythic royalty, even by the standards of the proud Dream of the Endless.

Additional details of power and aspect link the Three in Sandman to the Hempstocks in Ocean. Both sets of women employ thread, needle, and scissors in their magics in a way that references but does not duplicate the classic Fates. The Kindly Ones in Sandman, as we have seen, knit lives as clothing. Similarly, the Hempstocks perform a feat Lettie calls “snip and cut” to alter memories and events – Gran snips a piece of fabric out of the young narrator’s pajamas with “a pair of scissors, black and old” and re-sews them with “a long needle, and a spool of red thread” (Ocean 95-96). When she is done, only the Hempstocks and the narrator remember the evening’s true events; his parents no longer do. Gran has altered their lives by altering a garment in a way that feels immediately familiar and yet is unique to Gaiman’s world.

Three non-sequential panels taken from Sandman: The Kindly Ones, pt 1 1-3.

A small detail in both Sandman and Ocean provides additional metaphysical illumination of the Three Ladies. While the neo-pagan model associates the waxing crescent moon with the Maiden, that association does not hold true in Ocean; Lettie tells the narrator, “Gran always likes the full moon to shine on this side of the house. She says it’s restful, and it reminds her of when she was a girl” (Ocean 105). This links the Maiden (Gran’s youth) to the full moon, a possibly-confusing association to modern pagans that is explained by an invocation used by a witch in Sandman who is invoking the Three in a protection spell. “I consecrate this circle to Her who waits beneath the Earth, and to Her who makes life on the Earth, and to Her who shines coldly above the Earth” (Kindly Ones, pt. 7 15). This invocation casts the associations in a different light and explains why a full moon would remind Gran of her youth. “Her who waits beneath the Earth” is the Crone, an aspect of the underworld goddess of death. “Her who makes life on the Earth” is clearly the Mother aspect. And “Her who shines coldly above the Earth” is thus the Maiden, meaning all moon phases belong to the Maiden, and the full phase is merely the greatest bloom of that power. Further, moon goddesses are linked directly to water, which is why the Hempstock’s consistently refer to the pond as belonging to Lettie.

Food is also an important element to both triads. The Three in Sandman are almost always shown eating while they converse, though they are as likely to be eating a whole, live mouse as a ginger snap. Likewise, the Hempstocks serve food to the young narrator of Ocean each time he visits, and it is the best food he has ever had.

I was scared of eating food outside my home, scared that I might want to leave food I did not like and be told off, or be forced to sit and swallow it in minuscule portions until it was gone, as I was at school, but the food at the Hempstock’s was always perfect. It did not scare me. (Ocean 147)

Ones, pt 1 3).

The food theme, and the difference between the grotesqueness of eating a live mouse versus the wholesomeness of the Hempstock’s meals, speaks directly to the reason for the surface discrepancies between the two triads. In Sandman, the Three are seen being invoked only as agents of cosmic providence, and in Lyta Hall’s specific case, retribution. As their names change, so do their aspects – character, manner, appearance, and even the rules by which they must operate, though many rules do always stay the same.

This is why the Maiden says, “F’r example, you wouldn’t want to meet us as the Kindly Ones,” because in that aspect they must be terrible. Near the beginning of Sandman: The Kindly Ones, the Crone grumbles that she doesn’t know why they bother fulfilling their functions when people merely complain about their lives no matter what. The Maiden answers, “We bother because we have no choice. Because that is what we are, in this aspect.” (emphasis mine) (Kindly Ones, pt. 1 2)

The Hempstocks, then, are simply a different aspect of the Three Ladies, one that is more grounded in the mortal world and more concerned with the positive, nurturing aspects of the principle of the Feminine Divine. Lyta’s greatest need is to avenge her son, thus she invokes the harshest, most bloodthirsty aspect of the Three. The young narrator of Ocean, by contrast, is desperately in need of companionship, nurturing, and compassion… and the Hempstocks manifest and provide him those comforts. Lettie becomes his friend in play and adventure, steadfast even in danger and hardship, willing to sacrifice everything she is to keep him from harm in a way no other being in his life has done. Ginnie cradles him to her breast at the worst moment of his life, and Gran becomes a luminescent empress and drives away the most horrible monsters he has ever seen. And throughout the tale, they clothe him, bathe him, and feed him the best food he has ever had. The nourishment they provide sustains him in more ways than he can understand, throughout the course of his life.

Gaiman’s particular blend of the mythic and the brutally real gives an uncanny power to his writing, and his mythos has become developed enough across multiple works now for readers to be able to pick out certain leitmotif characters and themes. As Malone remarks in “Excavating and Restitching Myth,”

Gaiman has been writing for long enough that he’s created and populated a fictional world that slides in and out of his works, and this isn’t the first mention of the Hempstocks. […] …but the family has never been so fully realized until [Ocean]. They have transcended whatever fable Gaiman originally plucked them from and grown into a creation all his own.

(Sandman: The Kindly Ones, pt 13 24).

Maiden/Mother/Crone, Lettie/Ginnie/Gran, Alecto/Tisiphone/Megaera… whatever you call them, however they appear, Gaiman’s Three Ladies are a welcome staple in his worlds. He has said that if he had not been a writer, designing religions would have been a pleasant vocation, and in her article “Kid Goth,” Dana Goodyear adds, “Writing comics afforded Gaiman his great opportunity to invent a cosmology.” The Three Ladies are a keystone of that cosmology, and the final line of his Acknowledgements in Ocean is a thank you directly to them. “And lastly, my thanks to the Hempstock family, who, in one form or another, have always been there when I needed them” (Ocean 181).

No doubt they will continue to be there for his readers as well.

Works Cited

Conway, D.J. Maiden, Mother, Crone: The Myth and Reality of the Triple Goddess. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 1994. Print.

Farrar, Janet & Stewart. The Witches’ Goddess: The Feminine Principle of Divinity. Custer, WA: Phoenix Publishing, Inc., 1987. Print

Gaiman, Neil. The Ocean at the End of the Lane. USA: HarperCollins, 2013. Print.

—. The Sandman, Vol 1: Preludes & Nocturnes. Canada: DC Comics, 1991. Reprint collection.

—. The Sandman, Vol 2: The Doll’s House. Canada: DC Comics, 1990. Reprint collection.

—. The Sandman, Vol 3: Dream Country. Canada: DC Comics, 1992. Reprint collection.

—. The Sandman, Vol 4: Season of Mists. Canada: DC Comics, 1992. Reprint collection.

—. The Sandman, Vol 9: The Kindly Ones. Canada: DC Comics, 1996. Reprint collection.

Goodyear, Dana. “Kid Goth.” New Yorker, Vol 85, Issue 46 January 25 2010: 48-55. Print.

Graves, Robert. The White Goddess: A historical grammar of poetic myth. USA: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd., 1984. Print

Malone, Tess. “Excavating and Restitching Myth: On Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane.” The Millions. July 18, 2014. Web. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

McLean, Adam. The Triple Goddess: An Exploration of the Archetypal Feminine. USA: Phanes Press, 1989. Print.

Schnelbach, Leah. “An ‘Accidental’ Novel? Neil Gaiman Talks about The Ocean at the End of the Lane.” Tor.com. June 20, 2013. Web. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

Walker, Barbara K. The Woman’s Dictionary of Symbols and Sacred Objects. San Francisco: Harper & Row Publishers, 1988. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Neil Gaiman like some others has become one of the hallowed authors who can do no wrong.

Amen! But I think thoughtful discussions like this article are even more important because of that.

The Hempstocks are beings far bigger and far more noble than we can comprehend.

Gaiman’s work does a great job of depicting these disparate ways of considering the magical. It is eye-opening. A wonderful read. It is, quite simply, magical!

I loved The Ocean at the end of the lane. Beautifully written and a good story. I also think it transcends ages. After I finished reading it, I picked it up and read it to my 6 and 9 year olds. They may not have gotten all of the points but they enjoyed it as well.

I totally agree with you about the story transcending ages.

I like your study about the Triple Goddess thing. Reminded me of Madeline L’engle’s A Wrinkle in Time and all the trinity (“There really was only one”) symbolism there (especially with how Lettie’s character turns out at the end).

My first draft of this didn’t include the Sandman material, and I planned on illustrating it with triple goddess references from other sources — L’Engle’s Mrs. Who, Mrs. Which, Mrs. Whatsit; Ordu, Orwen, and Orgoch from Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain; the three witch prophetesses from the original Clash of the Titans movie; etc. Had to cut all that when I added Sandman and I’m still a bit sad about it… so thanks for mentioning the first Three-In-One I ever encountered as a child. They’ll always have a place in my heart.

Your analysis was excellent.

Thank you!

Female archetypes are definitely the stuff of myths and there was no shortage of female archetypes in Gaiman’s story.

Love Gaiman and really enjoyed this analysis of his work.

The divine feminine is a powerful symbol. For anyone interested in this, check out “The White Goddess” by Robert Graves. Really powerful book.

In my opinion, Ocean is one of Neil’s greater works.

Not that his previous works weren’t great. However, their length and scope (especially the Sandman novels) have always lent themselves to the kind of self-indulgent writerly cleverness which, however intelligent, detracts from the overall narrative.

The brevity of this work, by contrast, makes it a lean and muscular beast. There is not even a single word too much.

I’m always amazed that Sandman was produced as it was — sorta-monthly, over a span of most-of-a-decade, serialized so nothing previous could be changed, edited, or redacted. Gaiman once said that publishing serially was like jumping out of a plane and knitting oneself a parachute on the way down. Given his relative inexperience at the time, it holds together really well.

But you are correct — Ocean is, by contrast, a much leaner, more focused story. I love them both for different reasons, but you can certainly see Gaiman’s growth as a writer when you compare the two.

My favourite book of his is “Good Omens” that he wrote with Terry Pratchet. It is pretty funny, and actually provides some pretty good insights into a lot of religious questions people have. It reminds me of an easier to read C.S. Lewis.

It is a very hard choice picking the “Best” Gaiman novel. I suppose my personal favorite is either Stardust or The Graveyard Book, while I would say his best is either American Gods or Anansi Boys, where he takes the Anansi character from American Gods and drops his sons into the middle of a P.G. Wodehouse novel. But, I absolutely love everything he has written, and I have read it all, up through the second volume of Sandman (which has the recurring 3 Women motif…).

It’s hard to pick a favorite. My heart will always belong to Dream, but if I had to pick something besides Sandman it would be Neverwhere.

I feel like all of these novels and characters inhabit the same world, and I suppose they do in Gaiman’s imagination. I can’t wait to see what comes out of it next.

Jim Butcher has set his entire series around the triple goddess

Basically, the triple goddess shows up in basically all his works, ever. He has a thing for it. It can range from being a huge part of it (Ocean, Sandman) to a relatively minor cameo (American Gods). My favorite game to play with his books is “spot the triple goddess reference”!

He often has similar themes but I find that his characters, settings, and plots are all very different in every one of his novels.

Neil Gaiman is the single most imaginative, creative, sparkling genius writing in the world today.

I’ve always been fascinated with the Triple Goddess. Very nice and lengthy work.

Thank you!

The theme of mythic beings at large in the ordinary world is one that Gaiman often revisits (Sandman, American Gods, Anansi Boys), it taps into a deep atavistic vein and continues to work for him and for us.

I have only read Sandman and American Gods, but I have seen Coraline. One thing I notice Neil Gaiman likes a lot is exploring why people tell stories and what they accomplish, usually through some kind of fantasy world parallel to our own.

I love that running theme as well, Cagle. Why we tell stories, what they mean to us, how they save us. It always touches me deeply.

Too much analyses for my taste! Gaiman is a writer, and I very much enjoy his written work! He is human, and hardly godly; I have no desire to worship the divinity of Gaiman at the altar of celebrity!

Neil Gaiman himself praised this article: https://twitter.com/neilhimself/status/492767827846504449

Holy cats. Figured it would come up on his (or his people’s) Google alert… did not expect a reference, let alone praise.

Thank you for posting this! I don’t Twitter, so would have missed it.

Niel Gaiman. I thank you.

The Hempstock women are a pretty clear representation of the Triple Goddess (the Maiden, the Mother and the Crone) and have appeared (in different form) in the Sandman series. This is a great article outlining how.

Another example would be Magrat, Nanny Ogg and Granny Weatherwax in the Discworld novels.

Ah and I’m also looking forward to the next Gaiman novel, apparently he’s planning a sequel to American Gods which is still my favorite work of his (tied with the Sandman series)

Thank you for the praise.

A sequel to American Gods? Do you mean Anansi Boys, or is there another coming that follows that one?

I’ve made a point not to notice any similarities in his work.

Lovely post.

Thanks, Louie!

Thank you for providing such and interesting and straightforward article about the Triple archetypes…

Thank you!

I remember a friend lending me one of her Sandman books, which prompted me to search for the rest of the graphic novels in the series. Neil’s writing saved my high school years and gave me something new and exciting to look forward to in my graduated years. My first of his novels to read was American Gods, and it is still one of my favourite stories.

I think writing and stories have saved a lot of us, including Gaiman, which is why the power of Story is so often a theme in his work.

Gaiman needs to do a sequel to American Gods.

Neil Gaiman is one of my “must read everything they write” authors.

I enjoyed your indepth article.

Thanks!

The experience of reading ocean at the end of the lane will not leave me swiftly, as my sister hinted when she handed it to me and then became reticent about its wonders. She left me to find the superlative description of the book on my own, and for that I am grateful.

I’ve been meaning to read the Sandman series for a almost 4 years now, but just never got around to it.

I really enjoyed the first volume. When you are coming into the graphic novel as a newbie it takes a little while to get into the flow, but you soon get into the rhythm and begin to pick up the subtleties of both the graphic and the novel. The whole idea of Morpheus being an Endless and controlling the Dream realm was very foreign to me, but I really enjoyed the trip down the road of destruction and chaos when control was pulled from his grasp. The trip to hell was particularly fascinating. I’m glad the story of Nada is brought to light later in the series. He certainly doesn’t forgive easily, but he definitely shows compassion throughout. Although it is hard to discsern between compassion and him simply wanting to maintain the order of things.

The Ocean at the End of the Lane, touching places in my heart only monsters and love could find and attach themselves too.

I can’t think of the words to properly describe my experience with Ocean. Few novels are perfect, and to be honest I wouldn’t know how to recognize one. I’m sentimental. My lower lip began to tremble when our hero’s kitten was first mentioned. And Ocean…oh Ocean. Perhaps one of the (myriad) reasons I so love Mr. Gaiman’s books is his literary treatment of cats. Despite its book being not nearly long enough (my heart, already broken by the final pages, was wrung to bits when the story was “over”) it touched on so many epic elements, most notably the Hempstocks, the Maiden, Mother, and Crone. What the borrowed books, the remembered songs and childhood rhymes were to our young hero, this book was to me. Both heartrending, and comforting. It’s the kind of book you hug close to you when you finish.

I bought Sandman the moment it hit the shelves.

Me, too. 🙂 I had read his Black Orchid, which was the first work he did for DC, and when I heard the same author was doing a creepy and original take on Sandman, I added it to my pull list sight unseen. The rest, as they say, is obsession. Er… history.

His stories are about everything…and most of all, what it is to be human.

Well, I first heard of Sandman not long after being turned on to Neil Gaiman some years ago by my girlfriend. I was not interested in comic books that much at the time I began reading the series, but this series changed my mind completely. I have the first eight or nine volumes of the series, and have read them over and over again for two reasons. The first is because they’re just that interesting, the second is because the artwork is just that good.

Good post. Gaiman has not let me down!

Thanks!

His writing is so lyrical and beautiful. And it’s an interesting meditation on life and memory and the magic of childhood.

I love Neil Gaiman’s mischievously fun writing.

Gaiman is a master of writing an adult story about the stuff that frightens us in our childhood. He takes us back and makes it real and true.

This is absolutely fantastic! I wish I could have provided some criticism for you but I’m all out of ideas. Thank you for writing this! I love all the mythological background you provided. So interesting!

Great read! I’m becoming a Neil Gaiman fan. His stories are so different and unique (well, at least to me), and I plan to pick up more of his work.

It’s always a sad moment when a Gaiman novel ends.

Gaiman is a great read. I also appreciate his poetry.

Gaiman is one of the best writers I have found at making subtle and exciting allusions to other works. Especially Sandman. Sandman has lots of great “Easter eggs” and allusions to other DC works.

Really thorough analysis. I have created several lesson plans for Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series and one of them (“Knitting with the Fates”) explores the triple goddess archetype in conjunction with teaching students to knit. Students are asked to consider how women’s hand crafts like knitting are valued and passed down in society. Your exploration of this particular feminine archetype is incredibly relevant when considering how women are valued as creators of art and as characters within it. I will definitely be using the information here to enrich my lesson with a more complete picture of the triple goddess archetype.

Oh! I think you need a spoiler warning before your section on the Kindly Ones. You give away Gaiman’s magnificent climax!

I can’t believe I haven’t read more of Gaiman’s work- now I REALLY want to read all if it!

This is a great look at the triad in a different light.

Awesome article! I love Gaiman and am curious to see what you think about his myth-making about America in his novel American Gods. It is a fantastic book if you have not read it yet you should!

I have loved Gaiman’s work since I first read the initial run on “Sandman” and later his many works of prose writing. I did note when reading “Ocean” the Hempstocks were very much like the three sisters in “Sandman,” and liked that you brought that into your analysis of the subject.

What an article! Absolutely love how Gaiman uses various mythological concepts throughout his work. Didn’t see this connection.

Thanks, Joseph; glad you enjoyed it!

love love love!!!!!! Have you managed to watch American Gods yet?