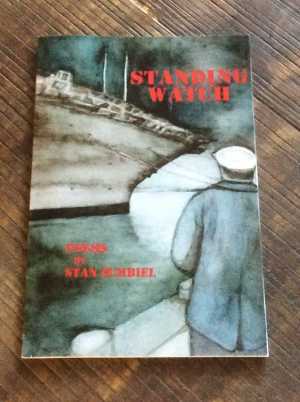

Poetry: An Appreciation of Repetition in Stan Zumbiel’s “Standing Watch”

In Stan Zumbiel’s chapbook Standing Watch, the phrase serves as title to both the collection as a whole and to its eponymous fifteenth poem. The repetition is significant, for “Standing Watch” the poem is, at least in part, constructed from salvaged or repurposed bits of other poems that precede it in Standing Watch the collection. That is, “Standing Watch” the poem seems very much to stand watch over Standing Watch the collection—to, as the poem puts it:

[…] walk the length of the dark and sleeping ship

a strange, cold circle vaguely lit, one end

of the hard pier to the other, tall gray steel

alive with shifting shadows looming close (30)

And this eerie passage isn’t quoted here only because it so beautifully describes the process of standing watch, but also because it too is subject to repetition—to replantation, as it were: six times verbatim after having first appeared in seedling form; then in slight topiary modification; and finally in full, mature flowering as the four lines quoted above. And if these two cases were not enough to reinforce the sailor’s perspective on the repetitiousness of his task—to, perhaps, let the reader (or listener) experience some of the monotony herself of standing watch—Zumbiel employs an even subtler repetition when he describes the process of beginning and ending the watch: appropriately, at the beginning and ending of the piece.

(cover art © Lynn Zumbiel)

For a 101-line, 18-stanza poem, “Standing Watch” is packed with repetitions—is, in fact, almost entirely constructed of them: some internal, others externally sourced. But Zumbiel achieves this meticulous patchwork without sacrificing the force of the piece as a whole by fitting each repeated form into something like the constituent parts of a quilt: first, by girding the poem at both ends (edging or bordering it, perhaps) through repetition of a significant image (the actual changing of the guard); second, by structuring the poem with alternating content blocks (stitching it together almost) through repetition of meaningful lines to create each interstitial stanza (an example of which is quoted above); and third, by supplying the poem with external content (allowing it to become a discernible patchwork even) through the understated repetition of chunks of other, earlier pieces in the work as a whole (and setting those “comshawed” stanzas off in italics).

Repetition from Beginning to End

In line 7, Zumbiel writes “I resemble the sailor I relieve.” (29) There is repetition and continuity even in the changing of the watchman—even in the literal act being rendered in poetry. And these are the closing words of the first half of the first (or “edging”) repetition present in the piece. Going backwards from the above-quoted declaration, the poem minutely describes the appearance of the sailor—both his ensemble and his emergence from the darkness—in lines 1-6:

It’s dark always because of midwatch, mid

for midnight. […]

Inspected—spit shined shoes and pressed bell

bottoms, bleached white hat, peacoat and leather

gloves. I march down the gangway and onto the pier. (29)

Nearly a hundred lines and 16 stanzas later, the image is repeated—but in something of a pared-down, condensed reflection of the beginning—to close the poem in stanza 18 (lines 97-101):

There is still no light when I am relieved, when another

sailor, who resembles me with his dark coat and white hat,

marches down the gangway and onto the pier. His eyes

look into the night, seeking the same nothing, seeking

the same silence. (31)

Thus, the “strange / and cold circle” of “Standing Watch” (as the poem has it in lines 22-23) is closed; the loop, complete; the duty, done. But what happens in between? How does the sailor pass the time “look[ing] into the night, seeking the same nothing, seeking / the same silence”?

Repetition from Within

The literal answer to these questions may very well appear in stanza 2 just after the opening lines quoted above. Immediately following the description of the sailor’s appearance—after he “resemble[s] the sailor [he] relieve[s]”—the second (or “stitching”) repetition is initiated to complete line 7 and begin line 8: “I walk the length / of the dark and sleeping ship.” (29) And thus begins this unassuming line’s yeoman’s work in the piece, as it is destined to serve not only in every interstitial even-numbered stanza throughout the rest of the poem, but also in one other important office as well. In the final half of stanza 4, the line is reworked—pruned a bit and grafted with other material—but still carries the substantial makings of the verbatim repetitions to come:

[…] it’s better

than standing watch, better than walking that strange

and cold circle from one end of the pier to the other,

the tall, shadowy steel looming close. (29)

By stanza 6, the already partially quoted passage describing the process of standing watch makes its first appearance as the opening four lines (which should sound familiar):

I walk the length of the dark and sleeping ship

a strange, cold circle vaguely lit, one end

of the hard pier to the other, tall gray steel

alive with shifting shadows looming close (30)

and will thereafter be repeated verbatim (save a terminal period) as the opening to each of the next five even-numbered stanzas: that is, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16. The only other variation in each of the six stanzas in which this four-line set appears as bulk and prolog will be the fifth and closing line—different each time and unique. Thus, the repetition of this passage serves to regulate the monotony of the watch, its sameness and routine. It is precise, rhythmic, almost hypnotic in its predictable, military pacing of footfalls—its almost iambic cadence of pentametered poetic feet perhaps mimicking the steady pattern of drilled and literal ones: eleven steps out, ten beats back, eleven beats out, ten steps back.

Repetition from Without

Given all this (repeated images at beginning and end as well as a repeated series of lines throughout), almost half the piece is composed of internal repetitions—those that could be perceived from within the frame of the poem itself—with nearly a quarter of its 101 lines (24, to be exact) being actually reproduced verbatim. But what of the other half? What of the interstitial odd-numbered stanzas? How has Zumbiel incorporated repetition into what is not so easily perceived as repeated?

The answer is that he’s turned to his other poetic work, especially those pieces included in the fourteen poems that precede “Standing Watch” in Standing Watch, including the third poem, “David and Lisa: Starting in the Dark” for stanza 13; the fourth, “Shipping Out” for stanzas 9 and 11; the thirteenth, “Last Voyage” for stanza 15; and the fourteenth, “Self Portrait of Burial at Sea” for stanza 17. As for stanzas 3, 5, and 7, one might suspect these too are from other Zumbiel poems, but no evidence of this can be found within the pages of Standing Watch. Suffice it to say that the twin facts of their being italicized in the text just like the other interstitial odd-numbered stanzas are as well as their placement as interstitial odd-numbered stanzas in the first place seem to suggest that they too are bits of other poems—but for the purposes of this investigation of the poet’s work, their origins shall have to remain a tantalizing mystery.

Turning back, however, to the knowable stanzas in which Zumbiel has repurposed his own work, the repetition isn’t only telling once it’s discovered, but actually hinted at in the text of “Standing Watch” itself. In the final lines of the very important stanza 2—wherein the two instances of internal repetition are also present (and also presented in quilting order from the “edging” of image mirroring to the “stitching” of line recycling, and then finally on to the hinting at the patchwork pattern of other-poem quoting as demonstrated below)—Zumbiel writes:

I remember […]

[…] the slow passage of time, time expanding,

to slip lifetimes between each passing minute. (29)

And “slip lifetimes between each passing” stanza he does. If each even-numbered, repetitive, interstitial stanza is seen as a “passing minute”, a rhythmic framework into which “lifetimes” or, at least, the contemplation of a sailor’s lifetime might be slipped, then the calling back to previous poems, to previous scenes and experiences in the loose narrative arc of Standing Watch, is a masterstroke in the artistic (that is, poetic) use of repetition.

As the sailor of “Standing Watch” (the poem) does his methodical duty and stands watch, the piece unfolds to allow the reader to realize that the sailor of Standing Watch (in its entirety) is either thinking about his life in poetry or else is composing poems in his head as he “walk[s] the length / of the dark and sleeping ship” over, and over, and over again. In stanzas 9 and 11 of “Standing Watch”, he is either remembering stanzas 6 and 1 of “Shipping Out” imperfectly (as the punctuation and line breaks have been changed from the quoted portion of the latter’s stanza 6 to the former’s stanza 9, and the word order of the quoted portion of the latter’s stanza 1 hasn’t survived the transfer to the former’s stanza 11) or he is composing them on the fly, without paper or pen to record his thoughts as they come to him (10-11). He must either remember and record later, or be remembering from an earlier record to which he currently has no access as he stands watch. And the same can be said for the later stanzas: in stanza 13 of “Standing Watch”, the sailor is either remembering or composing everything (save the opening line) of stanza 2 of “David and Lisa: Starting in the Dark”, whose punctuation and line breaks have changed (7), while in the former’s stanza 15, again, everything but the opening of stanza 3 from “Last Voyage” makes an appearance (also with differences of punctuation and line breaking as well as the insertion of the line “waving farewell”) (25). And as a final example, stanza 17 of “Standing Watch”—in a departure from precedent—quotes the beginning portion of stanza 5 from “Self Portrait of Burial at Sea”, still changing punctuation and line breaks, but also limiting the repurposed chunk to a single, otherwise intact sentence from its donor poem (28).

In the end, what is all this repetition good for? Well, one answer must certainly be the reader of Zumbiel’s poem. “Standing Watch” has a visceral sense of military routine, of imposed structure, of forced and disciplined order. And yet it departs into flights of fancy, remembrances or imaginings, just as a mind will—must, even—when too much order is demanded of it. A second and equally valid answer could be Standing Watch the chapbook and, by extension, Zumbiel, the poet. For by including “Standing Watch” the poem, a reader is invited (but not obliged)—intrigued, but not “ordered”—to return to the rest of the book. Over, and over, and over again.

Works Cited

Zumbiel, Stan. Standing Watch. Sacramento: Random Lane Press, 2016.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I like the poem ‘War is Kind’ by Stephen Crane which uses repetition really effectively.

Repetition doesn’t necessarily mean a piece of poetry is wonderful, it does help it to stand out.

Interesting analysis. Many poets understand the effectiveness of repetition.

Stan Zumbiel is the new Edgar Allan Poe.

Citation needed.

Repetition in poetry is a powerful and effective rhetorical device.

Certainly sounds like he has gained the mastery of repetition. Great article.

Repetition can be so insistent that it spills over into obsessiveness.

I was just talking about repetition in my poetry class during a lecture about popular music and poetry. We were discussing why pop singers will repeat certain words, like a catch phrase or in a row (think “haters gonna hate, hate, hate, hate, hate). It was interesting to see how many different purposes people in the class thought repeating phrases had, and it shows how each poetic device can be made anew by a talented poet. My take was it was a sonic thing, as in the repeated the words like a classical composer would have the same note a few times in a row, resulting in a subtle emphasis on the phrase or note. Obviously, in this book, it takes on new meanings and boundaries. Great read.

LOVE IT!

There is a certain drama that captivated Zumbiel in this moment. It was his inspiration towards his poem. Something so simple and repetitive in his Poetic mind stood out from the rest. The rest would be those that have more busier duties and are running around forgetting about what life is about. The man standing watch is a simple man observing his life and all that surrounds him. He knows the value and appreciates every second that passes. It is as if the man watching is the one observing the reader.

Great Article 🙂

Wow, amazing just loved it!!