Pulp Fiction: How Tarantino Breaks the Mold of the Reactionary Gangster

In Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994), the audience observes a world portrayed from the gangster’s point of view. Only after witnessing the varying behaviors of the main characters in both their work and social environments can the audience truly grasp the complex essence of Tarantino’s characters.

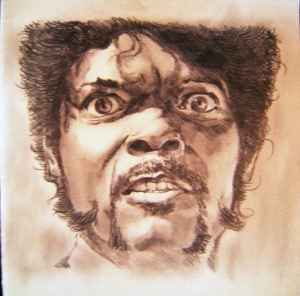

Until the end of the movie, one could possibly write off Jules, played by Samuel L. Jackson, as a heartless and reactionary exemplification of the typical thug. After all, we see this cold-blooded killer execute a man for no other reason than to intimidate and get inside the head of a man who has fallen short on a business arrangement with Jules’s boss, the infamous Marsellus Wallace. But after a “miracle” takes place that results in Vincent, played by John Travolta, and Jules not being shot down by a crazed combatant unloading his gun at the two from only feet away, an observant eye begins to notice a change in the ideological nature of Jules. The final scene in Pulp Fiction, sometimes called “the diner scene,” changes the audience’s perception of Jules and consequently the movie as a whole. This scene disconnects Jules from the expected characterization of the orthodox gangster, solidifying the notion that his role is progressive in nature. Pulp Fiction’s final scene harbors smart dialogue, unrelenting intertextuality, and methodically placed slow-cutting that effectively work against the reactionary portrayal of the standardized thug, while leaving the audience to decipher Jules’s convoluted moral revelation, in an otherwise Godless film.

Tarantino’s seemingly effortless ability to represent unlikely characters in complex and believable ways through dialogue is comparable to none. The character of Jules Winnfield is no exception. The conversation that takes place during the diner scene between Jules, Ringo (Tim Roth), and Yolanda (Amanda Plummer) epitomizes Tarantino’s ability to intimately connect the viewer with any given character through philosophical and thought-provoking conversation. After a long and eventful morning, Jules and Vincent enjoy a lazy breakfast at a local diner. As soon as Vincent excuses himself to use the facilities, a robbery unfolds. In an attempt to relieve Jules not only of his provocative wallet, but also of his glowing briefcase full of mysterious riches, Ringo loses focus long enough for Jules to instinctively grab Ringo’s gun, pull out his own, and consequently gain the upper hand of the situation.

But Jules must now deal with the firecracker Yolanda, Ringo’s accomplice and love interest, who nearly loses control as she imagines the thought of Jules blowing Ringo’s head off into oblivion. When Yolanda realizes that Ringo no longer has his gun, but rather is looking down the barrel of Jules’s, she jumps on top of a booth, points her gun at the man whose finger holds the fate of her Pumpkin’s life, and exerts a fury of inaudible demands and threats towards Jules, who of course has no intention of giving up his newly acquired leverage. Instead, Jules diffuses the situation by alluding to the lovable character from Happy Days, maintaining that all three of them act like three little Fonzies.

This allusion has the viewer beaming, when in real life one would almost surely be paralyzed with fear; that is, when a crazed robber is prepared to shoot you dead, it may not be appropriate to tell her to be cool like the Fonz. This behavior is diametrically opposed to the reactionary portrayal of a gangster. Gangsters do not want to defuse situations peacefully and make you chuckle, they want to kill you and take your things. Tarantino’s ability to make the viewer smile or even laugh at inappropriate times is one of his defining characteristics as a director and writer. This adds to Pulp Fiction’s authenticity, while also furthering the claim that Jules Winnfield transcends the stereotype of a dull and violence driven mobster.

As a career criminal, Jules has killed many people. But since witnessing a so-called miracle earlier in the day, Jules challenges himself to take the harder route by reasoning with Ringo and Yolanda instead of murdering them in cold blood due to inconveniencing him as per usual. But Jules isn’t simply going to let them escape unscathed. Even though he has experienced a moment of clarity, he still must leave these two amateur robbers with a keepsake; that is, if he won’t harm Ringo and Yolanda physically, then he sure as hell won’t let them leave without some psychological abuse. With a loaded gun pointed directly at Ringo’s head, Jules shares the fact that typically before killing his helpless victims he will recant his favorite bible verse: Ezekiel 25:17

The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the inequities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men. Blessed is he, who in the name of charity and good will, shepherds the weak through the valley of darkness, for he is truly his brother’s keeper and the finder of lost children. And I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger those who would attempt to poison and destroy my brothers. And you will know my name is the Lord when I lay my vengeance upon thee.

This is traditionally done for the effect; that is, it scares the crap out of people. This time, instead of merely regurgitating the bible verse in a feverishly insane manner before pulling the trigger, Jules slows down and tries to assign meaning to the strange portrayals of the evil man, the righteous man, and the shepherd. Although no killing takes place in the diner, and even though Tarantino’s artistic license drove him to rewrite a Bible verse (you won’t find this quote in your bedside Bible), the scene is no less bone chilling as Jules shares his sobering translation: that Ringo and Yolanda are the weak, while Jules himself is the tyranny of evil men. When Jules follows this up with, “But I’m tryin’ Ringo…I’m tryin’ real…hard…to be the shepherd,” the effect is captivating. The viewer can absolutely connect with this criminal as he wallows through his moral dilemma in an attempt to come to terms with his reality, and perhaps mentally disturb two wannabe robbers along the way.

As Jules begins to expand upon his newfound moral compass to Ringo, the audience experiences numerous 5-10 second point of view shots from both Jules and Ringo. In spite of the fact that Jules does the vast majority of the talking in this scene, we often see reaction shots from Ringo after Jules says something. When one can see Ringo, one can also see Jules’s out of focus gun, hand, and forearm seemingly protruding from the camera’s point of view as if the audience’s range of vision mimics that of Jules.

But as Jules begins to analyze the meaning of Ezekiel 25:17, something strange happens. For nearly 35 seconds, the viewer experiences the mesmerizing scene from a new and distinct angle. Tarantino decides to employ a half-minute long slow-cut that draws out the pure and unadulterated talent exuding from Samuel L. Jackson as he dissects and expounds upon the Bible verse. Contained within this slow-cut is a close-up of Jules’s face, emphasizing the subtle yet haunting facial expressions given off by Jackson. But instead of a shot of Jules from Ringo’s point of view, as was the case with the reaction shots leading up to this cut, Jules is now viewed from a position several feet behind Ringo. This causes nearly half of the mise en scène to be obstructed by the dark anamorphic figure that is Ringo’s out of focus head, a tactic that, while effectively blocking out nearly half of the screen, subsequently forces the audience to engage in a stare-off with Samuel L. Jackson.

After seeing 5-10 second back and forth point of view shots in the exchange between Jules and Ringo leading up to this cut, a 35 second slow-cut from this new angle disorients the viewer, while also emphasizing Samuel L. Jackson’s eloquent use of language and tone. The use of slow cutting as well as Tarantino’s decision to obstruct the mise en scène in this 35 second clip effectively brings extra attention to Jules as he gives his most compelling speech of the movie.

The dialogue, intertextuality, and slow-cutting present in the diner scene all work together to challenge the viewer’s stereotypes with respect to Jules. Without this scene, one might still argue that Samuel L. Jackson’s portrayal of Jules Winnfield is progressive in nature, and this may indeed be true. But the fact of the matter is that this scene solidifies Jules’s entry into the category of a progressive character, leaving one without doubt that the mold of the prototypical henchman has been broken. Pulp Fiction’s smart dialogue grabs the interest of the viewer, and at the same time allows one to feel comfortably immersed into the world being shown. Tarantino’s use of intertextual components contained within his dialogue adds to this feeling of immersion and authenticity. Jules’s final speech regarding Ezekiel 25:17 is highlighted by Tarantino’s choice to employ slow cutting. With nearly half of the mise en scène obstructed by Ringo’s blurry head, the eye’s of the viewer are invariably met with Samuel L. Jackson’s cold and calculated eyes for nearly 35 seconds, thus adding a disturbingly hypnotic dimension to this unimpeachably legendary scene.

By employing this technique, Tarantino leaves the audience with no other choice than to silently work through Jules’s philosophical analysis and subsequent conclusion of his favorite Bible verse, while at the same time challenging the audience to confront their own beliefs, and decide where they fall in terms of the evil man, the righteous man, and the shepherd.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

An interesting interpretation of the character of Jules but, I feel the case was better made with Vincent as he had the same chance but didn’t reform. Also, I disagree with Jules heart to heart with Ringo being a mere act of mental abuse. To be fair that comes from personal interpretation, but some of your points were just sour for me to read.

Hi thanks for the comment. Before I respond I would like to just say that the great thing about film is that we get to interpret scenes, symbols, and characters. This often results in disagreement between critics and fans alike, but that’s just part of the fun.

As for your specific comments, I would have to remind you of the purpose of my article: to show how Tarantino’s depiction of Jules breaks the mold of the reactionary gangster (and thus embodies a progressive character). A reactionary depiction of a gangster would be one that lives up to the common stereotypes of gangsters, e.g. drug user, violence-driven, hardheaded, possibly witty but usually unsophisticated, etc. A progressive depiction of a gangster would be one that transcends these stereotypes and thus moves the conversation forward so-to-speak with respect to what it means to be a gangster.

You claim, “the case was better made with Vincent as he had the same chance but didn’t reform.” This actually proves my point for me. The fact that Jules “reformed” and Vincent didn’t simply adds to the notion that Jules decided to disconnect with his role as the stereotypical gangster and thus move into a new progressive category. Vincent not reforming, threatening to kill Ringo and Yolanda (and Jules stopping him from doing so), abusing heroin, his issues with Butch, etc. all show why his role was much more in line with a reactionary depiction of a gangster. I guess I will chalk this one up to you seemingly not understanding my thesis or how I was trying to argue it.

You also claim that you “disagree with Jules heart to heart with Ringo being a mere act of mental abuse.” I will say that on this point, interpretation is key. I most certainly do not think that the conversation that unfolded between Jules, Ringo, and Yolanda was entirely for Jules’s amusement, or to simply psychologically disturb them. If you took that away from my article I’m sorry, that was not my intention at all. Instead, as I stated in the article, “Jules challenges himself to take the harder route by reasoning with Ringo and Yolanda instead of murdering them in cold blood due to inconveniencing him as per usual.” In light of his “moment of clarity,” Jules must come to terms with his moral revelation some how, and this just happens to be while being involved in a robbery. This is why he has the conversation about Ezekiel 25:17 with the two robbers, not for their sake, but rather for his own need to understand himself and what has happened to him. The fact that Ringo and Yolanda were very clearly disturbed after the encounter was not likely Jules’s main intention, but rather was a byproduct of his need to confront his new reality.

I am sorry the article was sour for you to read, but I find that when one stumbles upon a point of view different from their own, instead of viewing the conflicting interpretation as an attack or infringement on one’s own interpretation, one should try to make sense of the new point of view and try to reconcile how and why the other person came to that conclusion in the first place. I hope this helped clear some points out for you, please let me know if you have any further comments or concerns.

I’d also like to add that there seems to be a moral against the reactionary gangster. I mean to say that Jules is upheld as the moral victor in contrast to Vincent. Vincent dies in a poignantly nonchalant manner (not an oxymoron) to show that his life of crime made him into another listless death. Similarly, it’s the reactionary nature of the boxer and the crime lord that get them into a bad scenario with some rapists. It’s the boxer’s decision to leave their differences behind and help the crime lord that gets him out of his troubles.

This scene, for me, encapsulates everything Tarantino wanted to teach about the criminal lifestyle – that is to say, the protagonists and antagonists are not so different from each other. In fact, one could surmise that all the principle characters embody facets of both.

Yes, very well put. The fact that Tarantino often gives his main characters defects gives them much more of a humanizing appeal and thus the viewer is able to connect with them more so than a shiny and perfectly moral protagonist. Thanks for the comment!

Pulp Fiction is the movie I couldn’t explain why I love.

Somehow it makes the impossible possible, the unreal real, and the surreal classic.

Yes, none of the real life characters walk, talk or act that way, but that’s the point. It Could be real, and it isn’t. Isn’t that what movies are about!

For me, it’s all about Tarantino’s dialogue. I can’t begin to imagine the process that he goes through when coming up with a back and forth sequence between two or more complex characters. The guy is a genius.

Tarantino has achieved that very rare thing of completely revolutionizing a genre of film in the 90’s with Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction. Since then, no movie has even come close to having the kind of popularity that these 2 movies have had…

Yes, both are cult classics. I have seen pulp fiction probably several dozen times by now and it never ceases to inspire, intrigue, and entertain me. Surprisingly, I first saw Reservoir Dogs only last year (crazy I know). It did not disappoint.

Have you seen Jackie Brown? This is one of my favorite Tarantino movies, and many Tarantino fans I know haven’t seen or heard of it. It is a must watch.

Pulp Fiction is one of them films that needs a couple of viewing to grow on you and for it to be appreciated. Like appocolyse now . I hated it first love it now. Blade runner didnt like it love it now .

Definitely. Also, the fact that it is filmed out of chronological order requires one to go back, reexamine scenes, and check for easter eggs.

A friend and I showed Pulp Fiction to another friend who had never seen it one day and while we were enjoying and laughing throughout the whole movie, the new guy didn’t really appreciate it. And the exact same thing happened when I showed Apocalypse Now to my younger brother.

It’s funny though, most Hollywood films become way more boring after seeing it the first time.

I think Pulp Fiction is something of an acquired taste. The first time I saw it, back in about ’98 or so I think, I wasn’t particularly taken with it – it seemed trite, cliched and rather hammy at the time as I recall.

On the first viewing, I didn’t see anything in it that I considered funny – except for Marsellus’ immortal “…go to work on the homes here with a pair of pliers and a blowtorch … gonna get medieval on your ass!” speech. Not to mention I found the chronological dislocation of the movie confusing and disorienting to say the least.

But as I watched it again, first at a friend’s insistence and after that, more times out of curiosity to see if I could piece together the actual chronological order of events, I found it grew on me in a way I find difficult to define. I’ve since watched it maybe about 15 or so times; each time I discover something different in it, which I missed before, and it has become one of the high-rotation movies in my collection.

well the opposite happened to me. I used to like PF but now I don’t really enjoy watching it. the more I watch it the more stuff I find that is annoying

I never really fancied the plot structure of this movie.

I understand what you mean, but after seeing it so many times and realizing the subtle details and twists that could only be truly appreciated by viewing the scenes in the messy temporal order, I wouldn’t want it any other way.

I studied screenwriting and from what we learn, there are two kinds of structure : linear and episodic, linear respects the unity of time, space and characters, it’s the film with a beginning, a middle-act and an ending and not in that order necessarily, so you can have a linear plot with a few flashbacks and a non-linear narrative.

And the episodic structure is a film like Woody Allen’s “Radio Days” or “Everything You Wanted to Know About Sex” or Fellini’s “Amarcord”, many biographical movies for that matter, it’s not just about a specific plot, simply the narrator relating some episodes of his life.

Now, to which category “Pulp Fiction” belongs? I guess a bit of both, that some plot points aren’t explained doesn’t make the film plot-less, you have a feeling of continuity while you watch it… and the episodic structure became Tarantino’s signature. Maybe “Pulp Fiction” doesn’t have a plot but it rather a sum of three irresistible and brilliantly written subplots…

and yes, this is a great film.

PS: Another masterpiece that obeys nto both the episodic and linear structure is “Rashomon”.

For the three unities, see Aristotle (his is much more thorough than what you have described).

The characters are very interesting. How everyday’s life could lead to another, and relates. They were all perfectly staged, and quite amusing.

Yes, it doesn’t seem like the stories will intertwine at first glance, or even in the first hour, but they line up quite well somehow.

Jules’ choice to go do good deeds and walk the earth and perform good deeds seemed Quentin Tarantino kitschy wish fulfillment. That we can take anything Jules said at this moment, still winding down from his moment of clarity, at face value is pretty thin.

This is a good point, I think that after the initial effect wears off from the moment of clarity, Jules may reconsider walking the Earth as he claims he will. This is not to say that he will continue in the life of crime, for I don’t see that happening, but somewhere between the two extremes is where I would expect to find Jules down the line.

Great read! I love that you analyze the specific shots. I’m curious how you think this relates to the boxer and crime lord storyline, but I’m glad you did not try to cram it into your article. If, however, you happen to read this comment, I’d love to know your thoughts.

Hello! I’m delighted that you enjoyed it, thanks for reading.

As for the story between Butch and Marsellus Wallace, I find it very easy to cast Marsellus Wallace as a complete and epitomic instantiation of the reactionary crime lord. His motives are more or less predictable in the right kind of way, he does nothing to really force the viewer to take a second glance at him in order to reconsider his categorization, and thus he lives up to the stereotypical nature of his role.

One might argue that after Butch comes back to kill the rapists and/or rescue Marsellus, the character of Marsellus Wallace grows in moral magnitude by forgiving Butch of his disloyalty and letting him leave town (even though Butch is forced to leave town that very night). But ultimately, I think this act is more or less unsurprising and that Tarantino had no great scheme planned for Marsellus.

In terms of the character of Butch, I would say that I’m not really committed to espousing him with either a strictly reactionary or progressive role. As you mention above, Butch’s decision to go back after breaking free seems to point towards a moral enlightenment, and thus a move towards the progressive categorization. But if one is to make this argument, then one must cast aside the notion that Butch went back simply for the sweet taste of revenge upon his captors. Perhaps this is a more pessimistic reading of Butch and his motives for returning, but it seems that the argument could be made.

I think that one reason this scene is so legendary is simply because of the sheer terror that one feels when imagining being strapped to that chair, ball-gag in mouth, and becoming the next Gimp… not a pretty thought (not to mention that Comanche is playing throughout this scene, giving it a further hysterical and perverted dimension). The fact that Tarantino throws us this twisted curveball amidst a violent and high intensity fight scene between Butch and Marsellus Wallace is another reason it is so great. The fact that we are expecting to see this intense fight scene between the two drag on for a while longer and then end gruesomely for at least one of the two, and then we instead see these two powerful and commanding characters instantly be repositioned at the bottom of the totem pole—there is some sort of great message in this.

So to sum this rant up, I think that while the jury is still out on Butch, Marsellus Wallace is pretty clearly a reactionary character. One could probably make a convincing argument for and against Butch being one. The reason I chose Jules was because I think he was the most palpable instantiation of a progressive character, and I think it is rather interesting that we see a progressive gangster nonetheless.

I think Pulp Fiction is a microcosm of the criminal world, showing the whole spectrum from the disorganized robber (Pumpkin and Hunnybunny), the enforcers (Jules and Vincent), the kingpin (Marcellus), the pawn (Eric Stoltz’s Heroin dealer), the puppet (Butch), the expert (Winston Wolff), and the deviant mastermind (Zed). Jules is the character that the audience wants to see victorious, because not only does he get some of the best lines in the film, he’s the one that is never shown in a negative light.

Nice analysis, I think you define the characters nicely. I can see why you say that Butch is “the puppet,” but I think he breaks out of that category by the time the film is over.

Hello, I found your article to be well thought out and insightful in several ways. I particularly liked your emphasis on the individual shots within the sequence because their importance is often overlooked. I felt that possibly further exploration into the dynamic between Vincent and Jules would have served you well, especially considering how the dialogue between them and their disagreement over the significance of their experience within Brad’s apartment is what really shows the nuances of each character and how Jackson’s Jules separates himself from the typical thug character type. How they end up by the time the credits roll is clear evidence of your point as well; that Jules’ progressive nature kept him alive longer than his partner.

Quentin often uses character flaws to set up the fate of his characters. Travolta’s Vincent Vega is shot by his own gun while reading a book on the toilet in the middle of a break-in. He was just as passive and nonchalant about the ‘miracle’ in the apartment as he was when he accidentally shot off Marvin’s head. This was the same attitude he had when he broke into Butch’s apartment and it led to his equally apathetic demise. It may have also helped if he had noticed that something terrible happens every time he goes to the bathroom. Another example of a Tarantino character’s traits that pushes them to their death is that of King Schultz in Django Unchained. It is his irrepressible inclination towards overly complex and grandiose schemes as well as his desire to have the absolute last say that seals his fate. All in all, I enjoyed your article.

Hi thanks for the great comment, I am glad you enjoyed reading it! You make some interesting points here as well, and I think you are absolutely right that my argument could have been strengthened by further analyzing the dialogue between Vincent and Jules. Ultimately, I chose to focus on the the part of the diner scene after Vincent goes to the bathroom in order to keep the length of the article concise and also to explore two of the lesser remembered characters (Ringo and Yolanda).

I enjoyed the way you analyzed camera angles in the “diner scene.” I don’t know much about camera angles or film techniques, but I found your close reading of the scene well written and interesting. I’ll have to pay more attention to the “diner scene” next time I watch the movie.

Hey, thanks for reading. It is strange how camera angles can have such a strong effect on the viewer without one even realizing it. As you say, it often takes multiple viewings to really appreciate the nuanced angles employed by any given director.

Cool article. I love discussions about how camera angles affect the mood/story. And you picked a great movie to talk about. I enjoyed reading it!

Yes I agree, one of the often overlooked facets of film is the dimension created by camera angles and editing. Thanks for the comment, I’m glad you enjoyed it.

A very interesting study of the impressive climax of an especially impressive film. I feel compelled to take yet another viewing of it just to get a better sense of how well the camera contributes to the shift in Jules’ character that you’ve so well outlined.

I’m intrigued by the way you outline Jules as a “progressive” character, though I think perhaps there’s more that could be said about what exactly defines this quality about him; specifically, I see this in his response to Vincent’s insistence that handing over the money to Ringo is a waste:

“I ain’t giving it to him, Vincent. I’m buying something for my money…Your life. I’m giving you that money so I don’t have to kill yo’ ass.”

To me, this line in particular highlights the change that Jules has by now undergone, especially in comparison to Vincent, who previously insisted that his accidentally blowing an innocent man’s head off was just a minor, forgivable slip-up. We could probably take this contrast further by considering how we by now know that, the day after the diner scene, Vincent will meet an unfortunate but almost equally accidental end as Butch happens to one-up him, while Jules’ future is purposefully obscured and optimistic.

Regardless, this was an intriguing analysis, and has done a lot to help me further consider the character development within this film.

Thanks for reading, I’m glad that this article has allowed more people to appreciate the subtle influence of camera angles and editing techniques. You make a good point that more could be said that would further define Jules as a progressive character. I suppose I limited myself to the examples here because I wanted to keep the article relatively short, and also I wanted to highlight some of the lesser known facets of Pulp Fiction and film in general.

I think another interesting angle to look at in the case of the ‘righteous man’ is Butch. He decides to save Marsellus even after he double-crossed him in the fight fix, and knowing that Marsellus sent men out to kill him. Marsellus also, maybe through his own personal interests, forgives Butch.

Great analysis.