The Rules of Reviving a Genre: ‘Scream’ and Postmodern Cinema

Wes Craven’s Scream (1996) is a horror film that is often celebrated for its willingness to portray characters who have seen horror films. It is credited for reviving the horror genre after a string of disappointing sequels and direct-to-video releases in the 1980s and early 1990s, which left many fans and critics to believe that the once creative and lucrative genre was dead.

The $14 million film opened on 1,413 screens on December 20, 1996, making nearly $6 million in its opening weekend. As word of mouth and critical praise spread, the film wound up being the highest grossing slasher film of all time, earning over $170 million worldwide. What made Scream become such a financial and critical success, and what does its success suggest about 1990s cinema and culture?

To call Scream original is perhaps misleading. Though many critics and fans admire Craven for creating a fresh genre picture, the film itself is arguably original for owning its unoriginality. For instance, much of the film contains intertextual references to other works of art—especially horror—and these allusions give the film a postmodern self-awareness. Like other postmodern films of the 1990s, including Pulp Fiction (1994), Austin Powers: The International Man of Mystery (1997), and The Truman Show (1998), to name a few, Scream survives on the postmodern premise that the past is a recyclable source for the artist.

One of the ways Craven and the screenwriter Kevin Williamson display the self-referential nature of their film is through the characters’ knowledge of slasher film clichés.

The plot of Scream is not unlike other slasher films: An unknown killer who goes by the name of Ghostface terrorizes the suburban town of Woodsboro, California. The difference, as I have pointed out, is that the characters in Scream have seen horror films. For instance, one of Ghostface’s trademarks before attacking a victim is to call him or her (usually her) on the telephone and engage in a conversation about popular culture. In one of the film’s early scenes, Ghostface calls Sidney Prescott, our heroine, and the conversation is as follows:

“Hello Sidney.”

“Who is this?”

“You tell me.”

“Well I have no idea.”

“Scary night isn’t it? With the murders and all, it’s like right out of a horror movie, isn’t it?” (One of the many ironic lines of dialogue in the film.)

“Randy you gave yourself away. Are you calling from work because Tatum’s on her way over?” (Randy is one of the film’s supporting characters, who is a horror film geek.)

“Do you like scary movies Sidney?”

“I like that thing you’re doing with your voice Randy, it’s sexy.”

“What’s your favorite scary movie?”

“Oh come on, you know I don’t watch that shit.”

“Why not? Too scared?”

“No, it’s just, what’s the point. They’re all the same. Some stupid killer stalking some big-breasted girl who can’t act who’s always running up the stairs when she should be going out the front door. It’s insulting.”

It is significant, I think, to break down this conversation in order to understand the postmodern elements on display. On the one hand, the dialogue is tongue-in-cheek. When the killer quips, “It’s like right out of a horror movie,” we cannot help but smile because we understand that it is, indeed, out of a horror movie—the one we are watching.

The dialogue also acknowledges the countless slasher films to have come before Scream. When Sidney calls attention to the slasher clichés, it might appear that Craven is mocking the genre, until Sidney is attacked by Ghostface a few moments later and she comically runs up the stairs to find safety in her bedroom. What is especially clever about the scene is that Sidney’s efforts to be safe and avoid slasher clichés create more problems for her.

Sidney makes an effort to lock the front door—something characters in previous slasher films would disregard—but when she quickly opens the door to survey the scene (an act of idiocy or precaution?), Ghostface finds a way into the house and attacks her from behind. She rushes for the front door, but the lock is jammed, and she has no choice but to run upstairs and escape Ghostface’s clutch. This scene pays homage to slasher films and their clichés, but it also challenges condescending criticisms of the cliché by showing an instance in which running up the stairs is the wise decision, as Sidney’s only other option is death.

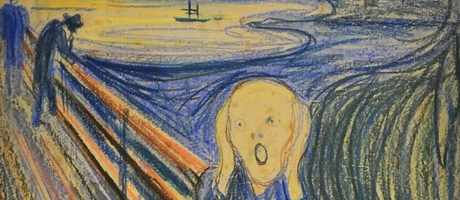

To further demonstrate its postmodern sensibility, the film contains allusions to other works of visual culture. For example, the white mask Ghostface wears pays homage to Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” an expressionist horror painting from 1893.

If we allocate Craven’s use of Munch’s painting for critical reflection, it is hard not to view it is an exercise in kitsch. Ghostface’s mask is an inferior copy of Munch’s brilliant, bewildering work of expressionism, and its existence as the identity of an unknown serial killer in an ironic, self-aware slasher film represents poor taste on behalf of Craven.

Moreover, the Ghostface mask has become a mass-produced commodity, as it is sold in toy stores all around the country and worn by children and teenagers on Halloween. Therefore, we find Craven breaking down the cultural divide between high and low art as he reimagines Munch’s avant-garde expressionist painting in a mainstream slasher film. These postmodern elements give Scream a cutting edge over other slasher films of its time, and they can explain why the film was such a hit with audiences and critics.

Another explanation for this, I think, comes from the film’s depiction of fandom. Make no mistake—Scream was made for horror cinephiles like Craven. In fact, it is one of those postmodern films that one needs to “get” in order to truly appreciate, like Pulp Fiction or Austin Powers. Without a background in popular culture and visual culture, the self-aware references, allusions, and in-jokes will escape the viewer. Whether making reference to Freddie Krueger, Tom Cruise, Halloween (1978), Hitchcock, Sharon Stone, or Munch, Scream is the kind of film that cinephiles discuss at coffee shops for hours, making lists and charts devoted to the film’s allusions, which become symbolic manifestations of their grasp on popular and visual culture.

Just as Scream is a film for cinephiles, it is also a film about cinephiles. Consider, for example, the scene in which Randy (Jamie Kennedy) interrupts a group screening of Halloween in order to explain the “certain rules that one must abide by in order to successfully survive a horror movie.”

What’s memorable about this scene, in addition to its intertextuality and self-awareness, is its depiction of obsessive fandom. The scene portrays a group of teenagers who form a community based upon their mutual love of horror cinema. With popcorn in abundance and videos of their favorite horror films to choose from, this communal experience becomes an event.

The rules of horror, according to Randy, are: 1. Never have sex. 2. Never drink or do drugs. 3. Never say, “I’ll be right back,” because, as Randy puts it, “you won’t be back.”

It doesn’t take long to figure out that Craven ends up breaking these rules with Scream. For example, Sidney has sex toward the end of the film, but she survives each Scream installment. The second rule does not apply, as most people at the party have a beer in their hand, and not all of them are killed in the film. Finally, the third rule does not hold, as one of the characters Stu (Mathew Lillard) jokingly says, “I’ll be right back” to the group, and we find out later in the film when he returns that he is one of the killers. It’s appropriate to assume that real-life fans would obsess over the ways in which Randy alters the rules, as I have just done.

Rather than representing fandom in a favorable light, however, Craven shows how it can be taken to the extreme, and the ways in which an obsessive love of cinema can lead to hyper-reality. Consider, for example, the murderous methods of Ghostface, and how he treats actual murder (at least in the filmic world of Scream) as cinematic. In the opening scene, he asks the film’s first victim Casey (Drew Barrymore) to answer various questions about movie trivia, and her level of cinephilia determines whether or not she will die. Here is a brief transcript of the scene:

“Name the killer in Friday the 13th.”

“Jason! Jason! Jason!”

“I’m sorry. That’s the wrong answer!”

“No, it’s not. No it’s not. It was Jason.”

“Afraid not. No way.”

“Listen, it was Jason! I saw that movie 20 goddamn times.”

“Then you should know that Jason’s mother, Mrs. Voorhees, was the original killer. Jason didn’t show up until the sequel. I’m afraid that’s the wrong answer.”

The exchange between Casey and Ghostface demonstrates the dangerous implications of fandom, and the ways it can lead to the hyper-real. Ghostface clearly has an understanding of horror cinema, and he deliberately asks Casey a trick question that she must answer in order to spare her life. She gives the wrong answer, and one can imagine a true horror fan watching the scene and thinking that any self-respecting cinephile would have known that Mrs. Voorhees is the original killer in Friday the 13th.

This question therefore separates those who are in the know from those who are not, but at what cost? Is knowledge of popular culture really a matter of life and death? Craven and Williamson seem to address these questions with Scream, as the killers are revealed to be two teenagers obsessed with movies. Billy and Stu, we come to find, have collaborated in the murders, and they learn all of their tricks, so to speak, from horror cinema. Below is a brief excerpt from an exchange between Sidney, Stu, and Billy after their identity is revealed:

“You sick fucks. You’ve seen one too many movies.”

“Now Sid, don’t you blame the movies. Movies don’t create psychos. Movies make psychos more creative!”

Billy and Stu are unable to separate the world of movies from reality, and as such, they treat actual murder as if it is a game, and they learn how to play it from the horror films they watch. It seems, then, that Craven is critical of fandom and its potential to overtake the cinephile’s consciousness to the point where film cannot be distinguished from reality.

Another way Scream resembles 1990s cinema is with its fascination of media and gadgetry. One of the new phenomenons of the time that Scream plays with is the proliferation of home viewing. In the opening scene, Casey makes herself popcorn the old fashioned way (presuming, of course, that popcorn was heated on a stove top before the invention of the microwave), but she entertains herself in an extremely new, postmodern way. With the help of the VCR, she watches a scary movie in her living room.

In a later scene that I have previously discussed, Randy and a group of cinephiles join together to watch Halloween and other horror films, and although the film is projected through a VCR on a television set, it is set up to mirror the theater-going experience. There are even perks to home video entertainment that cannot be found in the theater, such as the ability to converse with friends, drink alcohol, and as Randy does, pause the movie to explain the rules of surviving a horror film.

Another technological advancement that is prominent in Scream is the computer. When Sidney is introduced to the audience, she quietly types something onto her PC. In a later scene, she is being chased by Ghostface, and as I have previously discussed, she escapes by running up the stairs. Initially, Sidney reaches for the telephone to call the police, but the phone line has been cut by Ghostface. Since she is presented as a tech-savy teenager, however, she uses her computer to contact the authorities. Who knew that the computer would be able to save Sidney’s life in this way?

Audiences were most likely fascinated by the new gadgetry and its ability to take the place of the telephone, just as the home video takes the place of the theater. The computer can similarly be seen in the police department, as if the convenience of technology equates safety and security. Craven’s continued use of advanced technology, I believe, is an attempt to contextualize his film within 1990s consumer culture.

Finally, the prominence of the media elite finds Craven capturing the milieu of 1990s news sensationalism after the intense coverage of the OJ Simpson trial from 1994 to 1995. The character Gail Weathers (Courtney Cox), a determined reporter willing to exploit the gruesome murders for her professional benefit, is surely made to resemble the countless media reporters who capitalized on the OJ Simpson trial, as well as other personal-life events that are only considered news because they reach a mass audience. It is important to transcribe Gail’s final monologue, which are the last spoken lines of the film:

“Okay I think it’s going to go something like this, just stay with me. Hi, this is Gail Weathers with an exclusive eyewitness account of this amazing breaking story. Several more local teens are dead, bringing to an end the harrowing mystery of the masked killings that has terrified this peaceful community like the plot of some scary movie. It all began with the scream of 911, and ended in a bloodbath that has rocked the town of Woodsboro. All played out here in this peaceful farmhouse, far from the crimes and the sirens of the larger cities that its residents have fled. Okay, let’s take it back to one. Come on, move it! This is my big shot. Let’s go.”

This monologue, I think, encapsulates everything that makes Scream a brilliant, relevant film of the 1990s. We see, again, Craven’s postmodern self-awareness, but we also see the darker message at the film’s core.

Perhaps Craven constantly reminds us that we are watching a movie—even though we are—because in real life, gruesome murders and horrific violence such as the ones depicted throughout the film are often treated as such. The media turns violence into a spectacle, and it becomes an event that we read about in the paper or watch on television, as evidenced by Gail’s “exclusive eyewitness account” of an “amazing” series of murders. The final joke of the film—that somewhere a group of innocent people are being brutally murdered in ways that are real and not so funny—is one that we still haven’t gotten.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Scream has had a huge effect of the horror movie genre and has created a new tradition in the horror genre. Wes Craven has subverted and adapted the conventions to fit his film.

Billy’s line “We all go a little mad sometimes” is a direct quote from Norman Bates in Psycho.

Scream invented a new genre, the so-called “postmodern slasher flick”, and we will remain grateful for it. Even though all the sequels were terrible.

I like how this movie critiques its own genre, and then goes and deconstructs it, then rebuilds it up all again.

My all time favorite horror film, great blend of horror and self aware comedy.

I love Wes Craven’s cameo as Fred.

Watching it again the directing is really poor, but it does have its moments.

Scream really was the first to reinvent the slasher genre at a time, the 90s where the slasher genre was dead, it was all the rage in the 80s. What reinvented it was the use of self awareness of the slasher genre or “the rules”. At the time it really was fresh and “cool”. I would say the slasher genre now in 2014 isn’t very popular anyway. Sure some get made but most horror films are now found footage and possession type horror films.

The slasher genre was over by the 90s, Scream was able to put it on the respirator for another ten years with copycats like I Know What You Did Last Summer and Urban Legend.

There aren’t any movies identical to Scream that have reached the same level of success since. But you do have spiritual successors like The Cabin In The Woods which have caused a notable level of stir. And if we’re talking the lineage of the slasher, I’d say something like The Purge continues at least some of the tradition, and these have become enormous financial hits.

I agree on ‘The Cabin in the Woods’, not so much on ‘The Purge’.

I totally agree !!!!!! 🙂

I totally agree !!!!!!

After reading your article, I plan to re-watch “Scream.” I liked your comment on how Billy and Stu are unable to separate reality from movies. Great job!

Jon,this is one of my most favorite films, along with one of my most favorite art piece. I feel for Munch’s ‘The Scream’ long ago while pursuing my art studies. I enjoyed your paragraph on Munch and I wanted to put a positive spin on his work and Craven’s work. I feel that Craven has brought awareness to this particular piece of art work. I think a new generation has been introduced to an artist and an art movement that they may not have been exposed to, unless of course they studied art. Munch did three versions of ‘The Scream’ as I am sure you know. Another note on its popularity is that it has been stolen three times thus, giving the artist even more exposure to the general public. Overall you wrote a wonderful piece I appreciate the subject matter, the clips, the art reference and the lively writing. Great Job!

I think Scream was one of those unique movies that got a lot of things right during a time when horror movies were in a down period.

– iconic mask, voice. the actual story behind the mask is pretty funny too.

– homage to the slasher genre was a smart and fresh idea, the characters openly discussing old films and cliches.

– intelligent dialogue a good balance of humor, memorable characters

– the casting – that’s another aspect that made it work too, Arquette, Kennedy, Skeet Ulrich, Leiv etc. Neve Campbell was on Party of Five, Cox on friends which were popular shows at the time too.

Scream can easily be considered a piece of postmodern artwork for it heavily relies on the audience to understand the irony of the circumstance of the film.

I just absolutely love the first one. Everytime I sit down to watch all of them, I’m always tempted to just rewatch the first one instead of the rest of the series.

Yes the original is the best!! I actually watch that one the most. I love them all but the original in my opinion is the scariest!! Now with the MTV Scream TV series coming up in early 2015 I think I will be watching the original a lot.

Hollywood can’t come up with anything original anymore, I miss that

I feel that there hasn’t been a decent horror movie in a while, but on the other hand, I must also admit that my insight could be a whole lot better.

I actually have not seen this film, and your article makes me want to watch it. Really interesting piece!

I am kind of embarrassed to say I have never actually seen Scream. I watch horror movies all the time with my best friends but I think we avoided Scream because of it’s cliches… but I’ve gotta say, you have convinced me to watch it now! I never made that connection between Ghostface’s mask and “The scream.” What a clever thing to do! I realize I sound ridiculous for not having seen the movie already, but I’m now making it a priority to make it the next movie I watch. Really goo article!

I am curious how the television show will turn out. I have not heard much about it, but it will be great to watch if they can build suspense to leave you waiting each week.

I thoroughly enjoyed the Scream series not because of it’s jump-scares but because of the way that Wes Craven portrayed the psychology of someone, Sydney Prescott, who has been through something so traumatic and heartbreaking. To me these movies are more than just a serial killer, it’s a case study on a woman, or a team of people if you include Gale Weathers and Dewey Riley, who survive and are forced to face PTSD and Survivors guilt daily.

Beautiful psychoanalytic piece from my perspective as well as a wonderful horror movie.

Also a terrific article, thank you for the enjoyable read!

incredibly thoughtful analysis. thank you for writing this!

Scream begat to the world movies like the Scary Movie series.