Symbolism in the Western Genre: Love Thy Horse as Thyself

If you’ve ever seen a Western film, you know how integral horses are to the plot, and you know how critical they are to the Western hero’s mobility and success. After all, a mysterious fellow can’t ride into town without a horse, and he can’t ride off into the sunset either. But while horses have usually been seen as a Westerner’s tools, becoming more inconspicuous with greater importance, I want to bring them back under the observational light. Within the confines of the Western genre, horses are so much more symbolic than may first appear – and interpreting that symbolism can help us get a better grasp on the genre itself.

Genres, being categories of artistic composition characterized by similarities in form, style, or subject matter, are ripe with symbolism. Indeed, the way in which genres create and perpetuate a system of conventions – familiar characters performing familiar actions which celebrate familiar values – lends itself to symbolism, if only because symbols affirm a community of interrelated character types whose attitudes, values, and actions flesh out dramatic conflicts within that community (Schatz 455). And while generic symbolism helps to create a specific cultural context, understanding how those generic symbols function within that fictional context can be instructional with respect to our own, real cultural context.

Fiction and reality both rely on a system of ideas and ideals – we would do well to interrogate how and why those ideas and ideals operate. On a micro-level, marking and then analyzing meanings, themes, and patterns within specific genres can prepare us to perform similar analysis of the symbolism affirming real world ideologies.

The Western genre is devoted to telling stories set primarily in the later half of the 19th century in the American Old West. Like all genres, however, the Western undergoes a transformation wherein its classical period shifts into a post-classical and then into a revisionist period, with other phases in between. Nevertheless, despite the differences in how each generic phase treats the generic tropes, those tropes or conventions act as foundational elements for creativity. Perhaps the most interesting feature of the Western genre is that it is primarily archived in the filmic medium – as such, I will focus primarily on meanings, themes, patterns, and symbols elucidated by filmic methods (though not exhaustively, since the films often rely or comment on the literary basis of the genre).

The two most noticeable animals in the Western genre are cattle and horses. But whereas cattle in the West often seem to function primarily as plot devices, catalyzing the actions of the Western protagonist (i.e., they need to be driven to Kansas, they are stolen, they need to be sold) before declining in importance, horses induce a bizarrely compassionate and devoted sentiment in the heart of the Westerner. This fervent concern for and attachment to horses can be traced throughout the Western canon, and noting the consistent reverence shown for these animals (by protagonist and director alike) ultimately leads to the discovery of a curious slippage between human and horse in the Western genre.

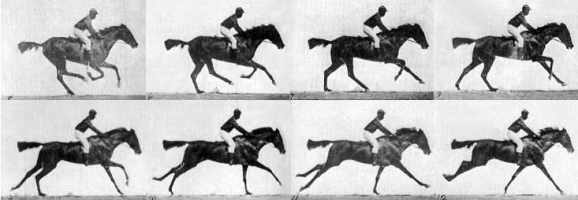

Perhaps it is even possible to trace such reverence beyond the parameters of the Western canon and back to the advent of cinema itself – the zoopraxiscope, considered to be the first movie projector, was an invention by Eadweard Muybridge created in order to study the horse at a gallop.

But, in the history of cinema, this fascination with the horse in motion inevitably gave way to that of the human in motion. In the Western we are afforded both. (As an aside: Muybridge, the man who ostensibly brought the horse to the screen, also shot and killed his wife’s lover but was acquitted in a jury trial on the grounds of “justifiable homicide.” Given his interest in horses and lust for revenge, it is difficult to think of a more apt model for the Western protagonist.) From the violent, determined rush of Virgil Earp’s horse towards the Clanton home in My Darling Clementine (dir. Ford 1946), to the wildly brash entrance of bareback-riding Martin Pawley in The Searchers (dir. Ford 1956), many of the Western’s most memorable moments of human characterization arise in conjunction with the dynamism of the horse.

But there is more than the directorial attraction to horses – the Western protagonist often has his closest bond with a horse, as seen in the relationship between the Lone Ranger and Silver (whom the Lone Ranger saves from an enraged buffalo, and who, in a remarkable show of gratitude, chooses to give up his wild life to carry him).

Whereas one’s fellow man may fail, horses are steady, and whereas one’s fellow man may turn to malice, horses are more often inclined to solicitude. Cattle are unimportant to the Westerner because to become emotionally attached to them would be to humanize an economic tool; a horse, meanwhile, is extremely important to the Westerner because it, being his ever-present companion, provides something beyond money. Somewhat perversely, Little Bill in Unforgiven (dir. Eastwood 1992) understands this horse to human connection: his solution to Delilah’s being cut in the brothel is to have the offenders give her a number of ponies, as if Delilah having them will make up for the cost of hospice but more importantly the loss of her pimp Skinny’s affection.

It is this presumed emotional connection between horse and owner that makes it clear that horses often stand in for humans in the Western. When Ben Stride walks into the desert cave at the beginning of Seven Men From Now (dir. Boetticher 1956) and tells the two men that Indians ate his horse, the revelation is followed by a heavy silence and then a roll of thunder. A sense of horror looms over this moment, as if the dramatic savagery of the Indians eating a horse is more akin to cannibalism than mere subsistence.

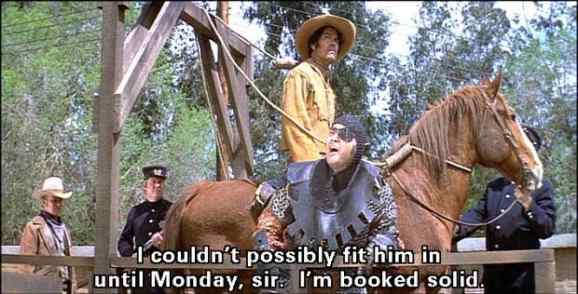

In fact, the killing or maiming of a horse is often more affecting in the Western than the killing of a man. More than anything, what keeps Will Lockhart in the town of Coronado in The Man From Laramie (dir. Mann 1955) is his fiery outrage at Dave Waggoman for shooting all twelve of his horses. Further, Shorty’s preternatural ability to communicate with horses in The Virginian novel puts the sale (and eventual death) of his horse Pedro to the notorious horse-beater Balaam on the same level of emotionality as the hanging of Steve – Shorty’s weeping foreshadows the Virginian’s, and just as Pedro’s sale makes Shorty express in private “the emotion he would never have let others see,” the Virginian waits until he is away from his fellow cowboys to mourn (Wister 158). That the two deaths motivate equally intense outpourings of private grief (not to mention Wister’s most potent writing) speaks to an appreciation for horses inconceivable with regards to cattle. Later, the equivalence of Pedro and Steve’s death will be taken up in a parodic – yet deeply perceptive – manner when we are given a shot in Blazing Saddles (dir. Brooks 1974) of a man and his horse, each sporting a noose and each about to be hanged; explicit in this shot is the assumed (in Blazing Saddles: absurd) connection between a man and his horse, as well as their equal value in the eyes of Western authority.

When it comes to the mythological machinery of the West, the horse is one of the key symbolic cogs. The sheer power of the horse as a symbol of the West is not lost on Ransom Stoddard’s opponent in the territorial convention during The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence (dir. Ford 1962), who pays a cowboy-actor to ride into the voting hall atop a majestic steed. The ostentatious display pleases the onlookers immensely, who relate the entrance of the horse with the opponent’s authenticity as a Western hero. Little more than the visual splendor of a horse is needed to perform the ideological work of an aspiring politician from the Frontier; the horse comes to symbolize the ideal attributes of the Western man.

Which takes us to the final shot of Wagon Master (dir. Ford 1950), where we see a foal crossing the river and presumably making it to the “promised land” where the Mormons will set up their community. There is an innocence and brashness to a baby horse, two characteristics well-suited to describe the leaders of this traveling community, but even so, it is curious that the conclusive image of this film should express the fertile genesis of the Western community by exhibiting a baby horse rather than a baby boy or girl. The slippage in the Western between human and horse becomes eloquently visualized here in the final shot of Ford’s film.

But this slippage is not exclusive to Western films – even the written impetus for the mythologized West includes such a phenomenon. Describing the Westerner in what amounts to an idealistic portrayal, Frederick Jackson Turner, in his influential essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” refers to this man’s “coarseness and strength” as well as the “restless, nervous energy” that allows him to conquer the harsh world around him – that wild Frontier that strips off “the garments of civilization” in order to return him to the mercy of nature’s laws (59, 33). From the start of the mythological West, it is a horse’s attributes that Westerners find most useful. The Western hero may be made in god’s image, but it is a horse’s qualities he seeks to embody.

Works Cited

Schatz, Thomas. “Film Genre and the Genre Film.” Critical Visions in Film Theory: Classic and Contemporary Readings. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2011. Print.

Turner, Frederick Jackson, and John Mack Faragher. Rereading Frederick Jackson Turner: The Significance of the Frontier in American History, and Other Essays. New York, NY: H. Holt, 1994. Print.

Wister, Owen. The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains. United States: Empire, 2012. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Great article.

Just like our possessiveness of our cars today, horses were the main mode of transportation. You mess with someone’s car/horse, you mess with them! But horses are so much more, like you stated. They have personality and can serve as a companion.

Nerdy addition: There is a Doctor Who episode, “A Town Called Mercy”, that plays up the horse personality in a funny way because the Doctor can speak with horses. He informs the horse’s owner that the horse wants to be called “Susan” and wants him to respect his life choices.

I like the horses ridden by John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, Henry Fonda, Paul Newman and Robert Redford…….plus the many differet television series with some awesome horses used…. I guess most folks didn’t think much would be made over “just” another horse, but some of them were really some very fantastic animals.

Showing my age, but in the 60’s-early 70’s, there was a horse with a big, almost bald face, and a quarter-sized dark spot just above and to the right of his left eye. I swear that horse was in almost every western movie or show. Keep your eyes peeled if you watch the old westerns.

My favorite one is in Dances with Wolves. Or the one in The Man From Snowy River.

This is very interesting article and takes me back to my younger days.

Great read.

I love your introduction of Muybridge. A fascinating man. Good job bringing his cowboy justice attitude to your article. I Look forward to reading your next piece.

Excellent read. I’ve never much been a fan of Westerns, but your piece makes me want to approach the genre again with new eyes.

Oh, the nostalgia! A very informative and engaging read, indeed.

The higher importance of the horse is very much a pre WWI mentality throughout the Anglo-American world.