The French New Wave

French New Wave — the highly influential 1950s French film movement that combined a minimalist production and an artful execution of philosophical themes — crafted a polarizing breed of art film never experienced before. The movement was led by a number of French film critics-turned filmmakers who not only made films that would define the New Wave movement, but would cement themselves as masterpieces of world cinema. This article is an introduction to the inception, the work, and the impact of the French New Wave movement.

On the Origins of the Movement

With the end of WWII came the end of Nazi censorship in France. Foreign films (and banned French films, such as the films of Jean Renoir) were allowed back into French cinemas for the public to view. American filmmakers such as Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, and John Ford — who were seen as artists who used a camera to paint with — began influencing French filmmakers. This was the birth of auteurship in cinema; that is, watching Vertigo (1958) didn’t feel like a Paramount Studios film, but an Alfred Hitchcock film.

In 1951, the magazine Cahiers du Cinema was founded which would eventually employ François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, Claude Chabrol, and Éric Rohmer as contributing writers; all of whom would become the founders of the French New Wave. These Cahiers created a list of principles regarding auteur theory — the idea that a director has so much artistic control over a film it is as though they are the author of it — and the elements that would define the New Wave. According to the Cahiers, a film should be a conversation between the auteur and his/her audience. Auteur theory was no doubt inspired from the heavily artistic and visionary styles of Hitchcock and Welles.

Influenced by preceding film movements such as French Impressionism, Italian Neo-Realism (a war-wrought kind of cinema focused on the hardships of everyday life), and Cinéma Vérité (a style of cinema concerned with ‘cinematic truth’), French New Wave centered itself around the idea of two things: art, and realism. This veered quite far from German Expressionism — an earlier film movement that focused on subjectively rather than objectively on the world, like French New Wave did.

The philosophical and artistic movement of Existentialism was extremely — if not overbearingly — influential on the French New Wave movement. The idea of human experience being the sole means by which to understand or achieve any meaning or value from life was a theme in almost every new wave film and dominated the philosophical relata in each. This lead to many of the filmmaker’s choosing to focus on either the subjective experience of their characters, or the objective world in which they operate. French New Wave is, in a way, the marriage of existentialism and art film.

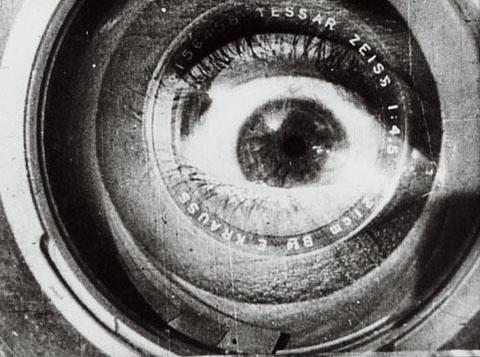

Sui Generis // Aestheticism

Cinéma Vérité was a style of filmmaking theorized by Jean Rouch, developed through the work of Dzigo Vertov, and later popularized by American indie film pioneer John Cassavettes. The idea of Cinéma Vérité is a cinema of extreme realism: that is, handheld camera work, natural lighting, no big sound stages or set ups, and often improvised acting from the talent. This idea is what makes film philosophically interesting: that a film can not only elicit some kind of cinematic truth, but can challenge the very nature of truth by parading its supposed “reality” with the fact that film itself is a veil of reality — something very unreal in its making. In this way, Cinéma Vérité can show the problem of truth and reality. French philosopher and sociologist Edgar Morin once wrote “there are two ways to conceive cinema of the Real: the first is to pretend that you can present reality to be seen; the second is to pose the problem of reality. There are two ways to conceive cinéma vérité: the first is to pretend you brought the truth, the second, to pose the problem of truth.”

This was one of the major distinctions New Wave filmmakers made: they were not interested in employing a semblance of escapism, but to constantly make the audience keenly aware that they are in fact watching a film, and that film is but a series of still photographs played together at usually 24 frames per second. Recognizing this problem of reality — in which the film is reaching for some kind of cinematic truth while itself being a product of artifice — was the philosophy of the movement.

The New Wave films, with their often heavy subject matter and low-to-no budgets, forced the filmmakers to devise new and creative ways to engage the audience. Arguably the most visually striking feature of French New Wave cinema — found most famously in Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless — is the use of editing techniques to distort the passage of time and drew the attention of the audience further away from the story, and close to the filmmaking itself. This was a revolutionary kind of filmmaking that was almost forbidden in cinema, until the New Wave.

Cahiers (Right Bank)

The Cahiers were François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, and Claude Chabrol. They were the kingpins of the movement by writing about its elements — elements which they would eventually show since they would all become renowned filmmakers. These film critics devised certain aspects of film that were solely interested in the artistic capabilities of the medium of film, not the traditional nor entertaining ones.

Claude Chabrol’s Le Beau Serge (1958) is cited as the first product of the French New Wave movement. The film follows a man who returns to his small village hometown to discover that many of his friend’s lives have changed and become more complicated for the worse. The film employs early techniques of experimental editing, handheld camera work, and, of course, real locations. The film was undoubtably inspired by Italian Neo-Realism with its look into the dark and cruel aspects of everyday life. Following and often compared to Le Beau Serge was Chabrol’s next film Les Cousins (1959). Like Le Beau Serge, Les Cousins was a dark narrative driven by personal relationships.

François Truffaut was one of the movements most prominent figures, and began his career by criticizing the Cannes festival for praising films with no artistic vision from the director. Because of this, he was banned from the Festival. In response, he made the cinematic masterpiece The 400 Blows which was the next big step in the New Wave movement. Thematically, the film pushes back again iconoclasm, nationalism, the ‘system,’ and other things that take away from individuality — which was a common New Wave trend. Aesthetically, The 400 Blows popularized the technique of having the actor(s) actually look into the camera, thus breaking the veil of reality within the film and reaching for some kind of cinematic truth. Surprisingly, film won Truffaut Cannes’ Best Director prize in 1959. In 1962, Truffaut would make Jules and Jim — considered to be an ‘encyclopedia of the language of film’ as Truffaut used newsreel footage, still photographs, panning shots, freeze frames, dolly shots, whips, masks, handheld camera work, and voice over narration throughout the film. While Jules and Jim had much more robust production, The 400 Blows would be what really inspired other Cahiers such as Jean-Luc Godard, who made Breathless the following year.

Jean-Luc Godard — one of the fathers of French New Wave and art-film in general — has been hailed by filmmakers Quentin Tarantino, Steven Soderbergh, Martin Scorsese, and many more as a master filmmaker. Throughout Godard’s magnificent filmography, he stylized and challenged every aspect of filmmaking from ‘point of view’, use of color, story-structure, and other visual relata. Godard made three extremely relevant films to French New Wave (and the history of cinema): Breathless (1960), Vivre Sa Vie (1962), and Pierrot le Fou (1965).

Breathless is arguably his magnum opus: his first feature film that also broke him into legendary status. The classic crime-romance drama was where Godard first used his technique of match cutting to distort the viewer’s perception of time. Godard also used next-to-no external lighting, and all real locations — such as apartments and open streets — for the entire film, so it took almost no money to make. Godard’s next film, Vivre Sa Vie is very aesthetically similar to Breathless but is structured with heavy voice over narration and dialogue that controlled the pulse of the film. Much like Breathless, Vivre Sa Vie was a dark philosophical look into the nature of identity and existential strife. Pierrot le Fou, unlike the previous two films, was shot in color and had quite a pallet. The film is famously recognized for its use of color as a means of visual storytelling and representation. The use of harsh primary colors throughout the the narrative was meant to allude to the dominant pop-art movement of the time. While the film is just as dark as Breathless and Vivre Sa Vie, it had a more theatrical aesthetic atop the heavy content.

Jacques Rivette’s famous Paris Belongs To Us (1961), cemented itself as one of the most culturally and aesthetically relevant films in the New Wave. Rivette wanted to solidify the ‘fragmented narrative’ trope while using the film as a sort of meta-poetic commentary on the New Wave movement itself, as the film featured cameos from fellow filmmakers like Jean-Luc Godard and Claude Chabrol. Rivette’s films, however, received little acclaim at the time of their release causing him to make only two other films during the movement.

Éric Rohmer, a fellow New Wave connoisseur, took the movement in a more ethical direction. His two most notable films include My Night At Maud’s (1969) and Clair’s Knee (1970). The former is the third film in his Six Moral Tales series, and famously discusses the validity of Pascal’s Wager, which is one of its main themes. It was also produced using funds that Truffaut helped raise since he liked the script so much. The latter is the fifth film in his Six Moral Tales series, and follows a career diplomat who becomes infatuated with a young girl’s knee while vacationing. The film is a study of desire, the human condition, and plays around Kant’s idea of the categorical imperative.

Left Bank

While the Cahiers (Right Bank) were off making groundbreaking pieces of cinema, the Left Bank was on the other side of the New Wave movement. Filmmakers of the Left Bank were much more concerned in challenging film form and creating very experimental films.

One of the primary filmmakers of the Left Bank, Anges Varda, was a photographer before making her debut La Pointe Courte in 1955 — which would become one of the great Left Bank films. Varda would later make the more acclaimed Cléo from 5 to 7 which included a cameo from Jean-Luc Godard. Cleo from 5 to 7 centered itself around feminism, war, and existentialism in France. Like many of her other films, Varda would challenge gender roles and the nature of absurdism throughout the film.

Another great figure in the Left Bank was Chris Marker who gained most of his acclaim from one short film called La Jetée (1962). The film was a science fiction narrative about a post-nuclear-war experiment done in time travel. The film itself, is almost entirely a reel of still images. The film makes many references to the work of Alfred Hitchcock, especially his film Vertigo (1958).

Alain Resnais would be known as making arguably the most prominent film in the Left Bank: Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959). The film used short flashback sequences to craft non-linear storyline — making it highly experimental. The film was originally a documentary about WW2, but eventually morphed into a romance narrative. This kind of interest in realism and WWII from Resnais was part of his auteur-istic interest with his real documentary about the concentration camps from WWII, Night and Fog (1955), was his debut feature.

Wither Not

French New Wave has had a profound impact on modern cinema and media in general. American filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese have made films aesthetically similar to auteurs from the movement. Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction and Scorsese’s Taxi Driver are arguably the filmmaker’s magnum opi, as well as their odes to French New Wave. Pulp Fiction employed the hand-held aesthetic, and used jump-cuts throughout the film to compliment its fragmented narrative. Taxi Driver presented a small production and had the feel of a documentary by being set in real locations. The film’s experimental editing also resembled the quick match-cutting of the New Wave.

American Sci-Fi was clearly influence by French New Wave. This can be seen through Terry Gillian’s sci-fi cult classic 12 Monkeys (1995) — inspired in many ways by La Jetée — and Michael Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) which was in many ways a homage to The 400 Blows.

Jacques Audiard’s films such as A Prophet (2009) and Dheepan (2015) are examples of many Cahier and Left Bank elements including hand-held camera work, a centre toward realism, and narratives with cultural and, albeit subtle, philosophical relevance. Abdellatif Kechiche’s 2013 Palme d’Or winner Blue Is The Warmest Color is also a modern example of the New Wave (especially Cahiers) influence — shooting in real locations, hand held camera work, primarily natural light, and being dialogue heavy.

In 1995, Thomas Vinterberg and Lars Von Trier created the Dogme95 movement in Denmark which shared many elements the French New Wave did — real locations, often improvised acting, and filmmaking that draws attention to itself. Trier and Vinterberg also, like the Cahiers, would write down certain rules for the Dogme95 films. They would eventually break these rules, but the similarity with French New Wave reigns true throughout their work. Films like Festin (1998) and The Idiots (1998) would define the movement.

Auteur theory itself has influenced countless American filmmakers today such as Wes Anderson, Paul Thomas Anderson, Michael Haneke, and Terrence Malick — all of whom have a distinct visual style to their work and deal with philosophical themes in their films. French New Wave even influences many “youtubers” today, as it has become a common trend to cut out the space between the words while they speak — a form of match cutting.

French New Wave was one of the most artful, creative, and significant film movements of all time that permanently enhanced the rigorous demand, inventiveness, and philosophical potential of film. The movement proved that quality films didn’t necessarily need money or high production value, but merely the vision of an artist.

References

Coates, Kristen. (2010). “French New Wave: The Influencing of the Influences.” The Film Stage. Retrieved from: https://thefilmstage.com/features/the-classroom-french-new-wave-the-influencing-of-the-influencers/

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The legacy of the french New Wave ( or Nouvelle Vague as we call it in France) is not very well known overseas, and especially in the US.

Yes, but that’s a concern for the Americans.

Are you considering doing one of these on the japanese new wave?

A reason that helped develop the french new wave was that during ww2, the french were not importing American films. so when the war ended and the films finally dropped on their laps (5-6 years of great american films) french audiences were unhappy with their own domestic productions and developed the french new wave.

I think what makes French New Wave really special was the involvement of critics who spent years studying film (which was obviously still very new) to make the movies they wanted to see and what others should see. I get the sense that it affected all of Europe in the long term (something we still see today), I hope the US gets a similar movement because we need it.

Crisp, insightful, informative, interesting!

I love foreign films especially French and Italian films.

I adore French New Wave and this is a good treatment of the subject. Too often when people are talking academically about the New Wave they alienate people by talking about the films as more ‘historically important’, like ‘you should watch this because it’s good for you’, rather than truly capturing why these films are some of the most creative, crazy and often ‘honest’ films out there. Great stuff!

I loveeeee French New Wave, perhaps one of my favorite genres! I think French New Wave and Neorealism just set a new stepping stone for the way stories were told in film and we even see in today’s films! Such a good article and definitely enlightening to us French New Wave lovers!

I had to watch Breathless, a french new wave film, for my film class, and I don’t know if I lost IQ points prior or I was really tired but that film made no sense. I also said the same thing with the Bicycle Theif and Citizen Kane. I literally had to read the wikipidea to understand the film.

Yes, that is what’s cinema all about. Very nice mixture of reporting and getting to the essence of making art, seen through every single movement of movie-making.

Great overview of the whole French New Wave! Bravo!!

It’s important to not make confusion between truth and realism. The New Wave film makers didn’t want to show the reality of the country. They just wanted to show their truth, a pure cinematographic truth, more metaphysical than tangible. Don’t go and believe that New Wave films represents the real french life of the 60’s-70’s. I’m french and I can tell you that it’s just false.

Love the French New Wave, true iconoclasts of cinema.

We wouldn’t have contemporary cinema without French New Wave. Japanese New Wave was also magnificent and very influential, happened almost at the same time, sometimes unrelated, to French movement.

I was talking about this in class today and so many of the reasons that Breathless had the style it did was because of its cheap budget. Like how the film was actually forty-five minutes too long so that’s why some of the jump-cuts or quick cuts in scenes were prevalent. Also it was all recorded without any audio so everything was put in post.

Jean-Luc Godard, “Breathless” 1959 in one of my favorite films.

Good and informative article! I really need to watch more New Wave

The filmmaker as an auteur concept existed before the arrival of the French New Wave. Directors like Kurosawa, Bergman, Renoir, Satyajit Ray, Powell-Pressburger, Luis Bunuel.etc. all established their command over the cinematic medium before the New Wave. However with the new editing and camera techniques introduced these French directors, cinema did change in a way and actually some of the old time directors also started borrowing some of these techniques to express themselves in their films.

A lot has changed in cinema since the French New Wave movement began, because of the digital movement. Now scenes appear real with the use of technology to enhance match-cutting, and to easily edit actors’ issues and absences, and other events. The use of technology in cinema can blow up a city, like the destruction of London in Babak Najafi’s London is Falling, with no physical harm done. But French New Wave films are works of art, and surely more philosophical with the existentialist underpinnings than today’s films. Most people take movies for granted and don’t think as much about the director as they do the screenwriter and actors – unless they study film, or the director is a household name like Hitchcock or Scorsese. Don’t get me wrong, I am excited with the advancement of technology in film and television and especially in screenwriting. But I truly appreciate the French New Wave founders in Kristen Coate’s article, who delivered us to this point.

I watched The 400 Blows in high school and it was a great movie depicting a different view of childhood, especially the ending.

I’ve seen about half these films so far. Breathless is my favorite, along with Rohmer’s Ma Nuit Chez Maude (1969).

Great article. Have longed been an admirer of French New Wave films.

I always find it interesting how the Left Bank makers, Chris Marker in particular, are almost always misrepresented and relegated to near footnote status, even though those makers were creating truly form and content challenging work. Of course, they did not have their own promotional print factory. 😉

Nice educational article, thanks!

The most magical of movements.

I think we should see the French New Wave not as a historical phenomenon but a movement of the continuous contemporary, particularly since its greatest filmmaker, Jean-Luc Godard, is still making films. One of the things that fascinates me about the New Wave is its response to technological innovation. If you look at Godard’s films, for example, you can see the typewriter (literally in Histoires du Cinema, personified by journalists in Breathless, Tout Va Bien, Comment Ca Va, etc.) as a formative influence on Godard’s conceptual of cinematic temporarily as discontinuous. In this way, the typewriter is the father of the jump cut. A more recent example: Godard’s use of cell phone footage in Film Socialisme. Godard presciently considers the liberatory potential of cell phone video just a year or so before one such video (the Tunisian street vendor’s self-immolation) would spark the Arab Spring.

What an extraordinary essay! woow, I am amazed.

Loved the article. I think a great follow-up piece would be on Japanese New Wave Cinema. Have you ever seen Seijun Suzuki’s films? Tokyo Drifter is INSANE!

I found this article to be quite a fascinating piece. It really opened my eyes to the different aspects of the French New Wave. Very well-written.

I took a French film class at my university last year, and when we were watching French New Wave films, I felt as if some had altered my perception of reality by the time I had gotten to the end, while I felt as if others had mentally zapped my willpower to stay awake.

The greatest films of the French New Wave remain fresh and challenging even fifty-plus years onward. Jacques Demy and Francois Truffaut are my favorite filmmakers from this movement.

Very insightful article, you managed to condense quite a bit of information and cover a film movement which contains a massive body of work while keeping your writing concise and interesting.

I just wished you had touched upon Jean-Pierre Melville’s films, but then again, I understand that going over the works of every major New Wave filmmaker wouldn’t make for a focused read; I just love Melville!

Very informative article, I find it interesting to see how different film movements have evolved over time and how they have affected and shaped everything from some of today’s most notorious directors and their films as well as every day “Youtubers.”

A friend of mine has told me about the New Wave; this article will serve useful for exploring a movie or two. Thank you.

You made use of some really interesting points in regards to this movement, I’ll now probably go and watch some movies from this time period!

Truly, this is my favorite film era. Maybe it’s because I’ve taken French classes for the past five years or maybe, growing up in Minnesota, I feel a connection to the culture. Either way, one could squeeze the innovation from these films. These directors did remarkable things with their films and it’s a shame how unknown and under appreciated these films are in the states.

This is actually really interesting. I have a friend who loves French New Wave and has started talking to me about it a lot. I think people have a lot of connection with this genre because of the emotional depth it creates. It isn’t anywhere near typical Hollywood films where things end up happy and wonderful. I mean, it can sometimes, but it is great that it has a more realistic outlook.

Never thought of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind as an ode to The 400 Blows. I’ll tuck that away for when I present on French New Wave in December. Thank you!

To the point of American influence, I could see a relationship between the American film noir to that of a French equivalent. Film noir is itself a French term meaning black film.