The Great Gatsby: Exploring 1920s Class Politics with Colour Symbolism

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel, The Great Gatsby, famously opens with the narrator imparting his own father’s sage wisdom. From a young age, he explains, his father advised him to withhold judgement as not everyone is given the same advantages in life. Ironically, the narrator spends the following two-hundred pages passing judgement on everyone in his life. Rather than a sign of poor writing; this hypocrisy points to the very crux of Fitzgerald’s novel.

Set in 1920s New York, the story follows the futile endeavours of Jay Gatsby. His goals are simple: he wants to become wealthy, join the upper echelons of society, and win over his married former lover, Daisy. Gatsby carries an abundance of hope and grows ever closer to achieving these goals. His attempts are ultimately unsuccessful though. Tom Buchanan, the upper-class husband of Daisy, is largely to blame for this. For this reason, the novel concludes with distinct feelings of anger and hopelessness. For both Gatsby and every other character, there is no happily-ever-after.

A deeply contextual story, Fitzgerald’s novel explores the division of social classes in 1920s America. He grapples with the idea of the American Dream and presents the stark contrast between its rhetoric and its reality. Through using colour symbolism, The Great Gatsby explores the limiting nature of class divisions. In a decade perceived as positive for social change, Fitzgerald shows that the narrator’s father was, indeed, correct. Not everyone has equal opportunities to achieve success.

Old Money and New Money

From the novel’s outset, Fitzgerald remains preoccupied with this theme of class divisions. Understanding what is meant by the term ‘class’ is an important starting point. Cambridge Dictionary defines class as “a group of people within society who have the same economic and social position.” Thus, ‘class’ is not solely synonymous with wealth, although it does form a significant part of it. As Fitzgerald’s novel portrays, the social aspect of class divisions holds just as much weight.

The Great Gatsby focuses primarily on New York’s richest citizens; but, even they are divided by pointless criteria. The author explores the rift between those with old money and those with new money. These distinct categories are illustrated with the colours of gold and green.

The Golden Buchanans

Old money refers to wealth which is inherited; rather than earned. Strictly upper-class, those with old money belong to families of great status. Within The Great Gatsby, the old money characters see themselves, and are frequently seen by others, as inherently superior. This old wealth is symbolised throughout the novel by the colour gold. This is likely due to its connection to the antiquated currency of metal gold. Tom Buchanan and his family and friends are associated with this colour.

This materialises in several ways throughout Fitzgerald’s novel; the first being in their physical possessions. On the first occasion that both the narrator and readers are introduced to the Buchanans’ Georgian mansion, it is bathed in golden sunlight. However, the way Fitzgerald phrases this is peculiar: “the front was broken by a line of French windows, glowing now with reflected gold.” Rather than simply stating that it is reflecting sunlight; the author is cautious to ensure that the reader imagines this home as golden.

Fitzgerald adds seemingly superfluous details to ensure these colour associations are never forgotten. One example is in Daisy’s offering of her “little gold pencil” to her husband. Ordinarily, the colour of a pencil would be an unimportant detail when setting a scene. Especially as, within the story, this pencil serves no crucial purpose. Fitzgerald’s deliberate inclusion of it, then, speaks volumes. As this occurs after Daisy’s reconnection with Gatsby, one interpretation of this event is that it is symbolic of Daisy giving Buchanan back his money and status. She palms it off nonchalantly; though she once cared for it enough to accept it, it is no longer his wealth that she desires.

This use of gold is not restricted to inanimate objects, however. Both Daisy and Jordan — a friend of the Buchanans — are associated with the colour. In two separate instances, the narrator describes Jordan’s body as golden. In chapter three, he holds her “golden arm.” Then, in chapter four, Carraway puts his arm around her “golden shoulder.” It is explained that Jordan spent her “girlhood” alongside Daisy. Thus, one might assume that she comes from a family of prestige also. This also accounts for her being one of the golden characters.

This characterisation is used with Daisy too; the woman is labelled “the golden girl.” Confirming the connection between gold and status, this label is given to Daisy immediately after the narrator likens her to a King’s daughter. Similarly, reaffirming that the colour gold is also symbolic of wealth, her voice is described as being “full of money.” It is not enough, though, for her simply to be golden. Instead, she is described as glowing with the colour. During a conversation, the narrator observes her as “the last sunshine fell with romantic affection upon her glowing face.” Her association with this colour is emphasised, perhaps more so than any other character.

Through using this colour when discussing the Buchanans — which, on its own, is associated with grandeur and riches — the implied superiority of these people is unmissable. Moreover, describing the women themselves as golden insinuates that being upper-class people from old money is an inseparable part of who they are. This implied permanence suggests that this is an unchangeable fact. Daisy may feel compelled to discard it, as shown with the pencil. However, as the novel’s conclusion demonstrates, she does not ever leave her comfortable golden life.

Gatsby, New Money, and the Colour Green

During the 1920s, the U.S. saw ideas pertaining to wealth shift in a way that should have seen social classes shift also. However, in actuality, it only solidified pre-existing divisions and created new ones. Following the devastation of the First World War, the U.S. experienced an economic boom. Americans were able to enjoy a rise in their incomes, and more people than ever before had the means to spend money on consumer products.

Thus, the notion of an ‘American Dream’ became prolific. The American Dream had always existed in some form since the nation’s inception. Prior to the First World War, this dream focused on ideas of being a so-called ‘self-made man.’ Individualism and hard work were key. Influential writings — such as the 1841 essay ‘Self Reliance’ by Ralph Waldo Emerson — famously expressed that success was marked by self-dependence. At its core, the American Dream dictated that working hard for yourself would bring you success and happiness.

However, by the 1920s — affectionately named the Roaring Twenties — this had developed into a dream inherently linked to capitalism. The core ideas were the same; hard work was supposed to get you anywhere. However, the goal of this toiling was to profit from the positive economic situation that occurred during the post-war period. Success was no longer marked by self-dependence; it was, instead, demonstrated by impressive displays of affluence. The American Dream became something of a rags-to-riches fairy-tale; the ultimate goal was to become wealthy and move upwards in social ranks.

This is befitting of Gatsby’s story; through hard work as a bootlegger, albeit an illegal profession, he was able to amass significant wealth. He, then, belonged to those considered to have new money, or newly earned wealth. Those like Gatsby were often referred to as the ‘Nouveau Riche.’ This deliberate invention of a new social class ensured those with new money were always separate from those with old money.

Contrasted with the Buchanans’ gold money, Gatsby’s new wealth is symbolised by the colour green. This can be associated with the modern currency of paper money. It is for this reason that many of his material possessions are associated with this colour too. The leather upholstery of his car is green. A guest is spotted drinking a bottle of Chartreuse, which he found in Gatsby’s home. This is a French liqueur that is either green or yellow.

The colossal mansion that Gatsby lives in is described as “spanking new under a thin beard of raw ivy.” The newness of his wealth is explicit here. However, the detail of his house being covered in raw ivy is also important. Not only is ivy a green plant, and Gatsby’s house covered in it, it is also described as both thin and raw. These adjectives similarly allude to a sense of newness. In the minor green details such as these, the fact that Gatsby’s wealth is so-called new money is present throughout the novel. It is always a focal point and never forgotten.

The Impossibility of Social Mobility

In reality, for many, the American Dream remained simply that: a dream. This forms the central issue of Fitzgerald’s narrative. While some managed to earn significant wealth, most were unsuccessful. The wealthiest members of society were recorded as earning more than what was earned by half of the country combined. Hard work was rarely a worthy opponent for dynastic inheritance.

However, it is the social aspect of class divisions — and the barriers it created — which receives greater scrutiny within The Great Gatsby. The newly rich were never accepted by those with old money. Though they may have had equal wealth; those from new money did not have the same status as those from wealthy families spanning hundreds of years. The sudden fluidity of the social classes was unsettling for those accustomed to being at the top of society. This certainly proves to be a significant point of conflict between Gatsby and Buchanan.

Within the text, Gatsby has the best chance of upward mobility, but he is never successful. In addition to the colour associations of Gatsby and his wealth, the colour green also represents the hopes and dreams of the protagonist. This exists both in the text’s minor details, and as a larger recurring motif.

As an example of a small detail, Gatsby recounts a story to the narrator, detailing who and where he got his initial funds from. By chance, he had met a wealthy man named Dan Cody on a yacht; the pair were fast friends. It was from this point that he entered the world as ‘Jay Gatsby,’ rather than with his birth name ‘James Gatz.’ This reinvention of himself rests upon his own hope that he could achieve more than who he was born to be. When Cody passed away, it was Gatsby who inherited his twenty-five thousand dollars. Thus, signalling the beginning of his attempts at upward social mobility. Uncoincidentally, when Gatsby first happened upon this literally life-changing friendship — as a young man full of hope — he was wearing “a torn green jersey.”

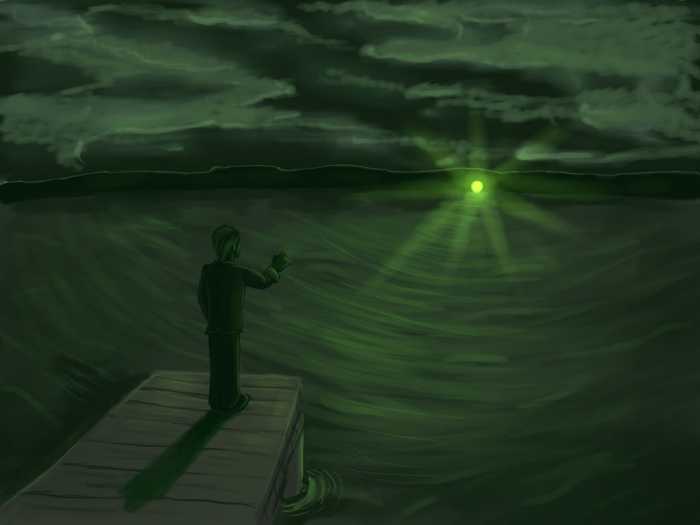

The most famous use of colour within The Great Gatsby, however, is in the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. Positioned directly across the bay from Gatsby’s home, this always-burning green light is representative of the man’s hope. The most important aspect of this light is that it is unreachable. Gatsby can see it, and clearly, but it is always too far away to touch. This matches his belief in the American Dream; he can vividly imagine it happening, but it never does.

The importance of this green light is stated explicitly throughout the novel. As the narrator notes in the novel’s concluding paragraph, “Gatsby believed in the green light.” In fact, the first sighting of Gatsby involves this symbol. He is spotted physically reaching for, not just looking at, the green light. Despite this, it remains “minute and far away” from him. Within the context of the novel, this occurs in the early days; before Daisy or Tom are aware of his existence.

Tom Buchanan can be understood as the single thing standing in the way of Gatsby and his dream. As previously mentioned, he is a member of the old money upper-class who is made uneasy by the protagonist’s attempts of social mobility. In fact, he despises the man. Tom labels Gatsby a “Mr. Nobody from Nowhere.” This unease only grows as Gatsby crawls closer to his dream. Consequently, Buchanan goes to great lengths to ensure that the bootlegger is never accepted into his inner social circle.

Buchanan admits to making “a small investigation of [Gatsby’s] past.” One reason that those from old money were so disapproving of those from new money was due to the often unknown sources of their wealth. To gain money as rapidly as Gatsby did, it was worried that the money would have needed to come from questionable means. This proves to be true of Gatsby, who became wealthy through selling alcohol over the counter. This was, of course, during prohibition when alcohol was an illegal substance. Worse still, it is suspected that Gatsby is part of another, more sinister, money-making operation.

This revelation is enough for Daisy — formerly so sure of her feelings for Gatsby — to cut ties with the man and remain with Tom. Just as she had chosen old money over new money in the past when she married Buchanan; she once again chose in favour of antiquated wealth and status. This signals the death of the protagonist’s American Dream. Even if his goal was to simply befriend Daisy, or any old money family, people like Tom would have actively intervened to bar it from happening. So steeped in tradition, the rigidity of the social classes remained in place. This is despite the widespread belief that anyone could achieve anything in the U.S. Thus, Fitzgerald’s expression of the futility of the American Dream is complete. As the novel concludes, the narrator sums this up:

“And as I sat there brooding on the old, unknown world, I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.”

The Illusion of Blue

The “blue lawn” mentioned above demonstrates another minor use of colour symbolism that shows the impossibility of the American Dream. The use of blue within The Great Gatsby can be interpreted as a hint towards how illusionary Gatsby’s dream is. This is confirmed by a scene after Gatsby’s death where the narrator describes East Egg — the part of New York where Gatsby and others with new money lived — as clouded by “blue smoke.” Smoke can blur vision and is often a key component of magical illusions. The fact that this reality-blurring smoke is described as blue confirms a connection between the colour and fantasy. In terms of basic colour theory, blue is used to make green. Therefore, if Gatsby’s hopes are represented by green, the blue suggests that those hopes exist, in part, due to pure fantasy.

This colour often appears when describing the physical aspects of Gatsby’s wealth. His home is frequently described as blue in peculiar ways. He is the owner of “blue gardens” that are filled with “blue leaves.” There is also his previously mentioned “blue lawn.” They are described in an attention-grabbing manner, as these things should be naturally green instead. Moreover, his shirts — the physical objects that reduce Daisy to tears as she realises how wealthy he is now — are monogrammed in blue.

These are the objects that Gatsby procured in his pursuit of the American Dream. His home was intentionally chosen to attract the attention of Daisy. He also parades his blue monogrammed shirts in a manner intended to impress her — “he took out a pile of shirts and began throwing them, one by one.” Alas, once again, his wealth is not enough. His inability to transcend social class divisions halts his dreams irreversibly. Gatsby’s American Dream is depicted as green; but its inherent reliance on the colour blue to exist demonstrates, once again, that he would never have been successful. Social mobility for Gatsby, and others like him, was never really a possibility.

The Significance of Yellow

Gatsby does get close to his dream of being accepted in the golden world of the Buchanans, though. Through the use of the colour yellow, Fitzgerald demonstrates just how close he does get. In terms of the colours themselves, yellow can be thought of as a fake gold. Therefore, this colour is infrequently — but cleverly — used when discussing Gatsby.

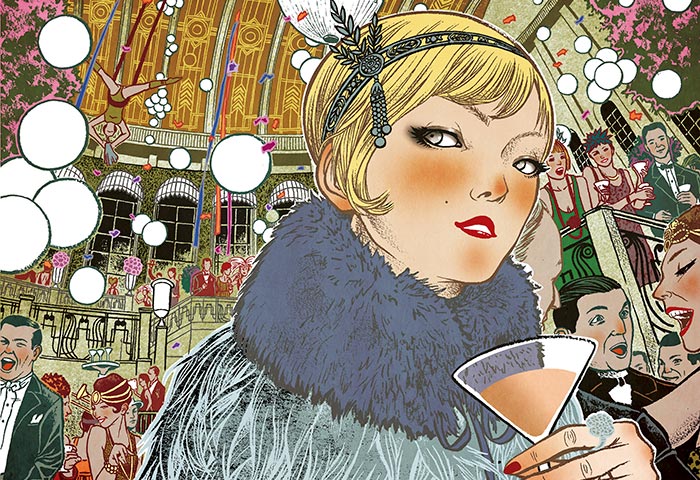

The most obvious use of yellow is Gatsby’s “big yellow car.” This ostentatious symbol of his wealth is cheapened by the fact that it is yellow. This, again, relates to his wealth being new money, and real gold being a symbol of the allegedly superior old money. His parties are described with the colour yellow, too. The narrator notes that the orchestra is playing “yellow cocktail music.” The narrator also seems to fixate on two guests who he describes simply as “the girls in yellow.” In fact, he mentions them five times; the other party guests receive one brief mention only.

The point of Gatsby’s parties is that they are loud and gaudy; those of high status — like the Buchanans prior to befriending Gatsby — often choose not to attend. When they did attend, it was rarely due to a sense of friendship with the host. As Tom notes, Gatsby’s parties were an expensive attempt to secure the man popularity. Instead of popularity, however, his home merely became a convenient hotspot for revelry. This is reflected in the fact that his guests often gossiped about him whilst at his own party. Their motivation for attending was never to share in the company of Gatsby himself. Thus, the yellow of his parties is symbolic of both his allegedly inferior wealth and — more importantly — the fake social status he thought his parties gave him.

At the novel’s conclusion, Gatsby is murdered. The narrator, who did form a genuine friendship with the man, put together a funeral service for him. Despite narrator Carraway’s best efforts, “nobody came” to mourn his passing. This further confirms how lowly Gatsby was perceived. Though his peers had no qualms taking advantage of the parties he threw, none of them cared enough to welcome him into their lives. If one chooses to see yellow as akin to fake gold, this can be understood as representative of Gatsby being so close to his old money peers; yet, still far away. He only got to experience an imitation of upper-class American life.

The Forgotten ‘No Money’

While reading The Great Gatsby, it is easy to get swept up in both the glamour and drama of New York’s high society. However, while those like Buchanan or Gatsby bicker over who is ‘better,’ the lower classes remain struggling and almost forgotten. For them, achieving the American Dream was unimaginable. Rather than fill them with hope, it often left them feeling hopeless. Those belonging to the lower classes were often employed in dead end jobs. There was simply no motivation to work hard for the American Dream when, for them, it was more like an illusion.

Grey or, perhaps more accurately, the absence of colour is used throughout Fitzgerald’s text to depict this hopelessness. There is no place more befitting of this description than the Valley of Ashes. Positioned almost halfway between the affluent and thriving East and West Eggs is the Valley of Ashes. Serving as the antithesis to the wealthy parts of New York, this place is introduced as such:

“A fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens where ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys and rising smoke and finally, with a transcendent effort, of men who move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air.”

This imagery of smoke and ash is descriptive enough for the reader to assume the Valley of Ashes to be grey and monotonous. However, Fitzgerald also overtly describes it as “grey” on more than one occasion. This includes everything from the land and cars, to the men who live there. According to the narrator, Wilson, a man who lives in the Valley of Ashes, blended in “with the cement color of the walls.” This matches his feelings and outlook on life; the narrator perceives him as entirely hopeless:

“Generally he was one of these worn-out men: when he wasn’t working he sat on a chair in the doorway and stared at the people and the cars that passed along the road. When any one spoke to him he invariably laughed in an agreeable, colorless way. He was his wife’s man and not his own.”

When compared to the lives of the Buchanans or Gatsby — imbued with gold or hopeful green — Wilson’s monotonous existence seems even more shocking. These disproportionately wealthy people can see the lower classes struggling. The closest they come to showing concern, though, is a snide comment about how a wreck outside his workshop means that “Wilson’ll have a little business at last.”

Fitzgerald’s use of grey here points to a distinct inequality present in 1920s New York. The Roaring Twenties are known for their colour; but that colour would scarcely bleed out to those who needed it most. It was impossible for those like Wilson to think of upward mobility when their greatest concern was mere survival. Worse still, their lack of colour means they are ultimately forgettable. In a novel concerned with inequality, Wilson should have been the centre; not just an afterthought. Yet, this depiction seems apt for a character who represents the millions of people forgotten by the American Dream.

One criticism that The Great Gatsby often receives is that the novel does not contain a single likeable character. Every individual depicted by Fitzgerald acts in ways that a collective readership would disapprove of. If this is the case, one must ask, who is this story’s villain? It could be Tom Buchanan; his rage and possessiveness was responsible for much of the tragedy that unfolds. It could also be Gatsby; his pursuit of the married Daisy was the reason many characters became intertwined in harmful ways. But, the real answer might prove to be more abstract.

Every character is ultimately a product of the system of class divisions thrust upon them. Each individual is fuelled by money or status; but this motivation has been cultivated. The pursuit of happiness became synonymous with achieving wealth and class. The American Dream enforced unrealistic — and ultimately disheartening — expectations upon anyone who was not already wealthy. For those who were wealthy, it made them act out of fear in order to protect their social position. Perhaps, then, the American Dream is this novel’s villain.

As previously discussed, Fitzgerald opens his novel with the unfair truth that opportunities for success are “parcelled out unequally at birth.” In the chapters that follow, he continues to demonstrate just how fundamentally true this observation is by using colour symbolism. Through colouring the lives of each character with a different colour, Fitzgerald has demonstrated how subjective the experiences of the American Dream are.

For those from the upper-class, including the Buchanans, the American Dream simply did not colour their lives. They had already achieved the desired gold and, thus, did not need to dream bigger. But, for Gatsby, his life was transformed into a kaleidoscope — or perhaps more appropriately — an optical illusion by this unobtainable dream. Green, blue, and yellow; the confusion of every colour meant that Gatsby was unable to see clearly just how destructive his pursuit was. Finally, for the lower classes, this dream, or illusion, drained them entirely of colour.

Through utilising every hue in creative ways, the author helps readers to find meaning within its narrative. A different colour for a different experience; Fitzgerald highlights the inequity of the U.S. in the 1920s. This is with great success, it seems, as generations of readers have associated a single green light with the impossibility of achieving the American Dream. This might, indeed, prove to be The Great Gatsby’s greatest legacy.

Works Cited

Cambridge Dictionary 2021, ‘Class’, Cambridge Dictionary [webpage], https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/class.

de Champeaux, J 2015, ‘The Access of the Different Social Classes to the American Dream at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century’, ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281279755.

Digital History 2019, ‘Why It Happened’, Digital History [webpage], http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook_print.cfm?smtid=2&psid=3432.

Fitzgerald, F.S. 1925, The Great Gatsby, Project Gutenberg Australia [eBook], http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks02/0200041h.html.

Olesen, J 2021, ‘Color Symbolism in The Great Gatsby’, Color Meanings [webpage], https://www.color-meanings.com/color-symbolism-in-the-great-gatsby/.

Pruitt, S 2018, ‘8 Ways ‘The Great Gatsby’ Captured the Roaring Twenties–and Its Dark Side’, history.com [webpage], https://www.history.com/news/great-gatsby-roaring-twenties-fitzgerald-dark-side.

Robinson, C 2021, ‘Jazz Age New York’, History of New York City [webpage], https://blogs.shu.edu/nyc-history/jazz-age-new-york/.

Strong Sense of Place 2021, ‘The Great Gatsby: F. Scott Fitzgerald’, Strong Sense of Place [webpage], https://strongsenseofplace.com/books/the_great_gatsby_fitzgerald/.

Zhang, H.B. 2015, ‘Symbolic Meanings of Colors in The Great

Gatsby’, Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 38-44.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Super quality article. Gatsby’s really a book that becomes clearer as the years pass, since it essentially deals with regret and the corrupting nature of time and ambition.

To me, it’s less about wealth than it is about the illusion of ambition, and how you can strive to reach a certain goal only to find that it isn’t what you thought, and then you realise that maybe you’ve lost too much in the process for it to be worth it.

Yes, spot Louis – I read it 15 years ago and didn’t really ‘get it’.

15 years and a lot of life experience later I definitely ‘get’ Gatsby in the personal terms that you describe – on a less personal level – the fact that over these 15 years wider society and the global economy have so closely followed the Gatsby world of boom, extravagance, inequality and bust only serves to underline the novel’s message and chilling prescience.

I first read Gatsby in a literature class when I was teenager, and I definitely did NOT appreciate its complexities then. It has to grow on you, I think. The reader will benefit from multiple read-throughs.

The mark of a great novel is that it has more than reading and yet it each reading really, really works.

Terrific piece, very well written. You have got to the heart of the book and why it endures.

All the characters in The Great Gatsby are ‘false’ in some way – Gatsby included. But the thing that separates him from the others is that he is constant in his love, and that’s what makes him ‘great’.

Or that’s how I understood it, at least.

Yes, I thought similar. He wanted to be wealthy for a reason, because he loved someone (who turned out to be a bit of a twat in the end unfortunately).

Similar to what i always took from the book.

An exceptionally thoughtful and well-written article. Happy to see that some media outlets still appreciate good writing and attention spans longer than 30 seconds. I certainly intend to follow.

I appreciate your kind words, busybock. I hope you stick around and read the articles of the site’s many talented and insightful writers.

I wish the films of this book didn’t exist.

I love the Robert Redford version, except for the choice of Redford himself. Though a splendid actor, he never gives me the impression that ‘he killed a man’ or bootlegged anything – he looks like the boy next door, whatever he says. But Daisy, Tom, Nick, Jordan, Wilson and Myrtle are wonderfully right and so is the setting.

Strangely, I had hopes for DiCaprio as Gatsby. I could see him as a character halfway between the naive Jack in Titanic and the bitter, self-deluded Frank Wheeler in Revolutionary Road. A missed opportunity. Sometimes I wish I could pick elements of each of the films and mix them together. I’m sure something passable would emerge.

But the real problem is that the movies are based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the novel. At the risk of being crass, Daisy is shallow, self-centered, immature and in no way worthy of Gatsby’s Romanized soft focus. Gatsby should have paid heed to the human molar cufflinks worn by Meyer Wolfshiem, which are the symbolic opposite of the distant green light. Gatsby’s tragedy is that once he attains his romantic vision, he insists on maintaining it in the face of all the evidence. And it kills him.

Hollywood, on the other hand, likes to pretend it’s a love story….

The 1940s version with Alan Ladd is OK.

I read The Great Gatsby years ago, and the only thing I took away was that Myrtle Wilson’s death was too melodramatic and violent (killed by a car, with some descriptive language).

The article offers great insight into the perception of wealth and class. It’s a good refresher for me and other people who read the book years ago, and it’s also a good summary for those people who haven’t read the novel but are or will become interested.

I’m puzzled why this is regarded as a timeless classic. To me it’s a tedious story of unsympathetic people.

Characters don’t have to be sympathetic to be interesting or relevant. Many of the characters are vapid and shallow and unsympathetic, as exemplified by the Daisy, who see’s her own daughter as little more than an object. Fitzgerald was criticising wealth’s hijacking of the American Dream in the early twenties, which led to many once innocent things (eg children) being objectified by a society that was obsessed with materialism in the guise of liberty. The novel wouldn’t work if you came out of it sympathetic of characters representing social attitudes that it is trying to condemn.

I don’t think I could have said it better myself, Carmen. The characters, each and every one, are unlikeable. But they’re supposed to be. Readers are supposed to fall in love with the opulence of Gatsby and the glamour of Daisy, and then they’re supposed to fall out of love with them soon after when they learn just how awful they are.

And things didn’t exactly improve in the subsequent decades and right up to the present! Which is another reason why we should be reading the work right now, of course.

And I am puzzled as to why you would find it tedious and the characters unsympathetic when so many of us find it neither.

What sort of books do you actually enjoy?

It’s about social climbing, greed, backstabbing and ruthless self-interest. That’s why it’s the great American novel!

That’s probably because you’re an unreliable reader.

I always felt Gatsby was a elegy for the loss of religion and that it captured the moment when the world decided, en masse, that it wasn’t the only game in town choosing instead the ethereal ghostly pleasures of earth bound romance to replace it.

Recently I was asked, I have just read this and want to read more books like it. I felt so sad when the question was asked. I don’t think there is anything else like it. That’s part of its magic and mystery. People call it a prose poem, suggesting its elusive form. It is as perfect as the sonnet that sings love at first sight in Romeo and Juliet.

Interesting about earthly romance replacing religion.

The Great Gatsby is not just about how wealth corrupts but how the corrupt consume goodness and the less fortunate. A perfect allegory for the world today.

Thank you for this intelligent and nuanced appreciation of the novel. Although I hadn’t yet read it then, I remember the 1970s Gatsby craze, which thoroughly put me off the idea of reading it. People celebrated the decadent glamour portrayed in the book and especially the film. When I finally read the book I saw that it was unmasking the moral and intellectual void of that glamour.

This highlights a clear distinction between riches and class very well (and is something not always obvious from an American perspective, where it is often seen as synonymous in contemporary times). This turned out well. Great job!

Thank you! I ensured to make that distinction crystal clear here, because I know how intertwined both terms often become.

Thank you. I’m a high school teacher in New Zealand and have taught “Gatsby” for virtually all of the last 38 years. Many 17 year olds fall in love with the book because it has so much to say to them about the challenges of growing up and the issues of today: the conflict between values built on sand and those built on rock makes for a- hopefully – unforgettable experience. Will share this article with my students.

Gatsby is wonderfully American, it sets a standard that you can compare with. Even Mad Men reminds me of Gatsby, for its ideas of reinvention, dream, illusion…. If there is other thing I think about, it is the book’s Mid Westernness behind the jazz age in New York. Another class conflict, the East Coast and the rest.

There’s two books I’ve actively avoided ‘The Great Gatsby’ and ‘Pride and Prejudice’.

Sorry, but now I have a vision of you running frantically down the street pursued by literary types waving copies of Gatsby and P&P trying to force you to read them.

He was later found facedown in a puddle of bootleg gin with an 18th century folding fan jammed up…

Gatsby is an okay read. In the right mood it is a great read.

P&P is a great read in any mood. I read it for the first time aged 47. It is a great read and well worth a Summer’s day or two 🙂

I am genuinely curious as to why you have avoided those two specifically?

Read somewhere that Hunter S “Gonzo” Thompson typed up the Great Gatsby in its entirety. Apparently he wanted to know how it felt to write like Fitzgerald.

I hate how the story ends and who Daisy turns out to be at the end. But on the other hand that is exactly what makes the story so captivating – Daisy, at first, portrayed as this innocent angel, that quickly turns into a weak and rotten human being without any redemption in sight.

Really loved this article. Excellent analysis of one of my favourite books.

Thank you for writing this article! I’ve never been a huge fan of this novel (though I do appreciate certain lines of it in terms of the quality of the writing), but the color analysis here has made me look at The Great Gatsby in a new way. Maybe I’ll reread it at some point . . .

I personally don’t think I’ve ever enjoyed Gatsby for the plot, and indeed, the first time I read it I wasn’t a fan myself. But it is one of those novels that I feel like I could analyse endlessly and I love that about it.

One of my favorite lines from the book is: “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy- they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.” I think it’s such a good line! And it perfectly sums up how unlikeable and superficial these characters and those like them could be. Contrary to what many readers might hope for, there is little newfound maturity or character growth to be had at the end as far as they were concerned. It’s an intriguing narrative choice to make.

So interesting!

Oh what a great piece. It makes me want to drink all cinematic versions after soaking in the original text and a roll around in the juices of the ages with nothing but contempt and sex on my brain.

This is a great novel, in its love and its hate.

For me the Great Gatsby sums up what is so wrong with excessive materialism.

Daisy won’t marry Jay because he is too poor so he effectively sells his soul to attract her and she ends up betraying her husband.

Very well written. Gatsby’s status as a classic has long been question but the way the novel comments on the illusion of wealth vs real wealth is and will always remain timeless. Brilliant comment on society and its values.

A masterpiece, if only it had been published in 1922, the annus mirabalis of Modernism. The Great Gatsby is definitely a Modernist work.

Brilliant novel but This Side of Paradise is my favourite by Fitzgerald and as good as any book I’ve read. There’s a beautifully worded and eloquent chapter when the protagonist meets a girl and the novel changes to the script for a play; for me that chapter just accentuates the joy of reading Fitzgerald. However, Gatsby is his most polished novel and obviously brilliant so I can see why it’s taught in schools/appears on these lists. What resonates with me is the utter despair if trying to fit in for Gatsby, a timeless and universal theme if ever there could be one.

The list of books I want to read is growing rapidly. I have This Side of Paradise on my shelf, but just not enough time to get around to it yet. I’m glad you enjoyed it and your comment makes me keen to read it.

Fabulous commentary. It’s been ages since I read the novel – and I saw Redford’s performance – but what sticks in the mind when most else is forgotten, is the richness (sic) of it – the mansions, gardens, clothes, parties etc., the size of the characters, and the awful underbelly it revealed. Betrayal not only of a people’s and society’s dreams, but a larger cautionary tale of betrayal of The Dream that we can make what is good of a fresh landscape if we don’t hold the real line in terms of values.

Thank you, and I completely agree. I think a lot of people associate The Great Gatsby with parties and wealth and just full blown decadence, and it’s because Fitzgerald portrays it so vividly.

Thank you for this wonderful article, Samantha. It is rare ability of you to write something both academic and entertaining. Much like most other great articles on The Artifice.

All time classic for me. Realities through an interesting character the divisions bubbling around American society and plays with v interesting narrative voice which English literature has struggled with…

This isn’t about how riches are corrupted, it’s how the corrupt feed nice and the poor. Indeed a fine universe allegory.

Your discussion of The American Dream and social mobility is perceptive. A well written essay.

It is a great book that can resonate even in the most unlikely settings, such as in season 2 of The Wire when D’Angelo and other prison inmates discuss the meaning of the novel’s last few lines.

I did not enjoy the book, although I recognised the quality of the writing, because I could find no empathy with any of the characters. Perhaps it was partly because I was born in 1931, and the period of the book was too close to have any resonance. Later on, that period was history and could be seen in a different perspective.

Without Fitzgerald’s writing, something will inevitably be lost.

“Gatsby” is weak. “All the King’s Men”, now THAT’S a real American epic, and the quality of writing is vastly superior to Fitzgerald’s.

I liked the book and I do think it’s a classic, though not up to the likes of Hammett or Chandler.

Oh, dear. You may like it better- that doesn’t mean it’s a better book.

It’s difficult in the present era of throwaway relationships to comprehend the extent of Gatsby’s romantic obsession.

The problem with Gatsby is that Tender Is The Night is a much better book by F Scott. Oh and that Faulkner is ultimately a better and more interesting writer than Fitzgerald.

The novel is like an eternal horoscope for the homeowners of the Hamptons.

I think your analysis of the impossibility of social mobility was apt. The impossibility of the newly-rich characters of high society in “Gatsby” to gain upward social momentum was probably the most striking representation of America’s socially constructed class system. However, it wasn’t until I read Isabel Wilkerson’s “Caste” that I knew of another established academic voice on the matter. Wilkerson posits that class, while determined by one’s passage through socioeconomic, academic, and/or social standing, is not the only category that defines one’s position in the general societal order. In short, class is changeable. The category of “caste” refers to the inescapable and inequitable categorization of someone according to status at birth regardless of how one may reinvent themselves. It has to do with the social position that one is born in and how they are defined for the rest of their lives due to social constructions. Gatsby is a victim of this caste system that was so prevalent in 1920’s America.

The impossibility of the newly-rich characters of high society in “Gatsby” to gain upward social momentum was probably the most striking representation of America’s socially constructed class system. However, it wasn’t until I read Isabel Wilkerson’s “Caste” that I knew of another established academic voice on the matter. Wilkerson posits that class, while determined by one’s passage through socioeconomic, academic, and/or social standing, is not the only category that defines one’s position in the general societal order. In short, class is changeable. The category of “caste” refers to the inescapable and inequitable categorization of someone according to status at birth regardless of how one may reinvent themselves. It has to do with the social position that one is born in and how they are defined for the rest of their lives due to social constructions. Gatsby is a victim of this caste system that was so prevalent in 1920’s America.

It is THE American novel of the early 20th century.

I love this article! I actually wrote a paper in high school on the color symbolism throughout Gatsby and focused heavily on his car and the color yellow, so I was familiar with some of the points you touched on from my own analysis but you introduced many new insights that I hadn’t considered especially with the color blue. Gatsby ages well so I expect that there will be only more to unpack in the years to come.

I agree completely. Mine is only one small interpretation in a sea of many. That is actually a big part of why I enjoy this book so much. Thank you for your kind words. 🙂

I read The Great Gatsby in high school and college, so I’ve talked about the color symbolism a lot. Bravo though, for focusing on blue and the “no money” grays, blacks, and other neutrals. Most people stop with gold, yellow, or green.

Excellent analysis! My junior year literature class’s color analysis stopped at gold and green, hah. This was a great refresher of my memory and a great insight into more overlooked color symbolism. This book wasn’t exactly my cup of tea back in 11th grade, but I might just give it another try soon!

The Great Gatsby is easily one of my favorite books, despite hating it in high school. As a young adult, I have a much greater respect for the book and understanding the book’s connection to the American Dream. This article is terrific and gives me a greater appreciation for the novel.

This is the first time I ever picked up the symbolism of colours throughout the literature and I find the interpretation rather interesting with the class division (although, to be fair, the last time I read it was when I’m only 14). The discussion about American’s sociopolitical landscape is rather standard, when you can see how the obsession of status and a supposed meritocracy played out for its (unfortunate) citizens.

One thing I’d like to add more into the analysis is the comment on the need for a likeable character and the question to divide a moral perspective on how their stories play out, and maybe to an extent, as an attempt to relate with their motives (“if I were you” kind of situation).

I kind of wish to read more about your take on the social isolation of Gatsby in order to trade for his new found opulence. As we trace all the character’s emotional infrastructure and yet for Gatsby, there was little to none other than his alone-ness through and through.

Amazing article! Wonderful analysis and great pictures.

Amazing breakdown of the book! Thoroughly enjoyed this read

Very interesting analysis. This article has definitely helped me to better understand the book.

I haven’t seen any of the early film and television adaptations of The Great Gatsby, but I would be interested to see if any of them tried to adapt the book’s colour symbolism through non-visual means such as dialogue, since they were limited by the black-and-white filmmaking technology available at the time.