The Marquis de Sade and Literary Terror

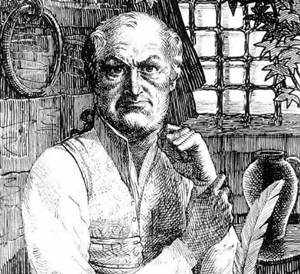

Donatien Alphonse François, the name does not stir in us any emotions. Perhaps for Francophiles it sounds elegant, to the untrained mouth it may be unwieldy, yet, to the educated listener that name is best known as The Marquis de Sade. Now, when one mentions de Sade a range of emotions may occur. We may be nauseated, disgusted, ashamed, reviled, stricken; we piece together what we know about him and dismiss him as being insane and dirty, we may even make the bold claim that his works should be consigned to the fires and never read by anybody with the least amount of sense. In many ways de Sade would agree with this, yet to relegate him to the annals of history as a mere aberration does not do justice to his work and it reflects badly on the modern reader. de Sade, for all his proclivities and gestures toward the lubricious, can also teach us much about literary terror.

Literary terror has most commonly been described and defined in connection to the rise of Gothic literature as a way to demarcate what is mere horror and what is worthy of being called terror. Supernatural fiction writers, analysts, and compilers continue to make the distinction between what is horrific and what is terrible, yet they often exclude de Sade. Critics will comment on Polidori, Shelley, Stoker, Radcliffe and even Tolkien but they rarely cast a glance in the direction of the Marquis. I pick up on the missed opportunity to explore the roots of literary terror in works of fiction that do not have supernatural monsters, yet fill the reader with terror as they turn every page. De Sade is a precursor to this Gothic literature precisely because his works are foundationally based on terror.

One of the earliest concepts of terror in literature comes from the gothic author Ann Radcliffe. In her short dialogue/essay titled, On the Supernatural in Poetry (1826) Radcliffe makes a clear distinction between horror and terror. For Radcliffe, “Terror and Horror are so far opposite, that the first expands the soul, and awakens the faculties to a higher degree of life, the other contracts, freezes and nearly annihilates them” (Radcliffe 47). She goes on to say that Milton, Shakespeare and Edmund Burke do not source horror as a cause for the sublime but they do cite terror. So what then is terror? It is a source of the sublime but moreover it engages the imagination. Terror is about uncertainty and obscurity, enough of each to make the reader wonder at what is coming next, how it has happened or why the character has done what they have done. Pure horror is unimaginative; it leaves nothing to the imagination and is played out in front of the reader.

This definition is supported by the 20th century horror master H.P. Lovecraft. In his long essay and history of gothic writing he makes the same distinction between terror and horror. While Lovecraft gives them different names the definitions stay the same. Like Edmund Burke, Lovecraft connects the notion of terror to pain and the menace of death. Thoughts of pain and death stay with us more readily than thoughts of pleasure, so any work that can tap into this primal psychological fear gives rise to real terror (Lovecraft 27). For Lovecraft this can be shadowy gods from other realms or the intense feeling of aloneness and separation that is felt by many of his characters. In any case, his definition stands united with Radcliffe.

When there is a deep psychological-imaginative fear present it can easily be turned to terror. Boris Karloff speaking about this distinction quips that terror is rooted in the cosmic (read primal) fear of the unknown. Horror, in contrast, is the gory and banal repugnance that we can find on the six o’clock news (Kaye xiv). This distinction between horror and terror is meaningful. It is very rare, if it even exists, to enter a book store and find a section that is dedicated to terror novels or a video store that specializes in terror movies. Yet, when these literary theorists speak about terror they often connect it to horror, a term that deserves some recognition.

Defining Horror

Horror, is disgusting, revolting and repulsive; it is often connected to monsters or beings that represent our worst fears especially those that make us feel unclean (Carroll 19). Horror and terror work closely together and are often inseparable. According to Stephen King, horror movies (as well as novels) work on two levels: there is the gross out level in which the monster kills or the demon makes a mess with human bodily fluids. This is the superficial level; it is a meretricious effect that is easy to employ and liable to fail if used too often (Kaye 610). This level sits atop a deeper structure that is necessary to make the novel/movie memorable and meaningful. The second level King says is more potent. Tt is part of the ever swirling danse macabre, “a moving rhythmic search” that is looking for where the audience lives at its most primal level (King 4). This is where the situations hit the audience on its “phobic pressure points”, areas of the psyche that hold our most deeply felt fears. Without reaching this level the novel, film or art serves as “gore porn” or appears as totally unnecessary instances of unrefined calamity.

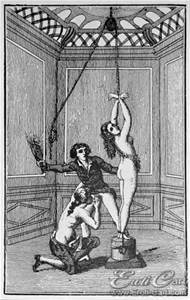

The monster in Frankenstein throttling the life out of a victim is horror, the abuses suffered by the “guests” in 120 Days of Sodom are horror and Satan becoming disfigured to represent his station in Paradise Lost is horror. Any brute overt act that is played out by the supernatural or the natural constitutes an act of horror. Horror is named after the affect that it is supposed to promote in the audience (Carroll 14); one should feel suitable horrified–unpleasantly surprised or shocked. In this way we see that horror and terror differ. Terror attaches itself to our psyche, makes us question, throws us into ambiguity and fear while horror is meant to shock us and revile us. It is because horror “does the dirty work” of killing and grossing out that these two terms are nearly inseparable.

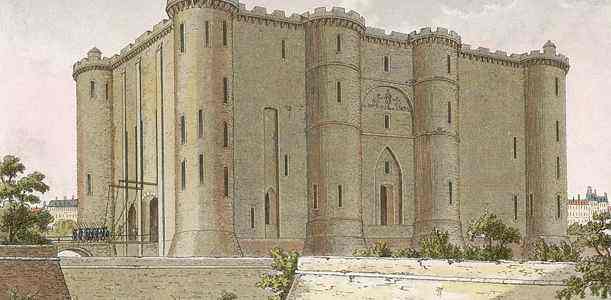

Consequently, it is this charge that is most often leveled against de Sade. Many of his contemporaries as well as modern readers charge de Sade with unnecessary horror. Rape, ejaculation, blasphemy, and irregular sexual attitudes are cited as being the main focus of his work. De Sade is regularly and continually subjected to the accusation that his writing is meaningless except to horrify the audience. To a certain extent this is true, the Marquis was writing in a politically tumultuous time (called the Terror) against a government that he did not respect. Therefore it is not a stretch of the imagination that he would use horrific images to make his point as evident as possible. Compound this with the generally conservative attitude of late 18th century French government and you have a truly radical author who would be speaking from a very particular standpoint—almost anarchic. Beyond the politics however, was a man who loved literature and dedicated a great portion of his life to writing. A contemporary of Horace Walpole who is noted to be the first gothic author, the work de Sade was producing must be understood as part of the foundation of gothic literature and as such a fundamental part of understanding terror.

Saving de Sade?

One of the authors who best understood de Sade was Simone de Beauvoir, French existentialist and philosopher. In her essay Must we burn Sade? de Beauvoir attempts to understand de Sade’s motivation for writing what he did without engaging in an overt political reading. Instead, Beauvoir gives a close reading to de Sade’s works and philosophically renders his logic through an existential lens. She says that the interest in de Sade is not with his aberrations, nor with the horror that he writes, but it is with the manner in which he accepts the responsibility for these opinions and beliefs (Beauvoir 6).

This pushes Beauvoir’s reading of de Sade into the realm of the psychological- into the realm of terror. Beauvoir goes on to comment on his love of literature and the reasons why he lived such a literary life. She says that the Marquis was in love with the ability of literature to grant him what society could not “excitement, challenge, sincerity and all the delights of the imagination.” (14) When de Sade writes to his wife vehement that it is not the manner of his thinking but the manner of others thinking that has been his unhappiness we do not hear a man who is preoccupied with horror, what we hear is a man whose ideas cannot be expressed in the way that society would like them to be. Again this is echoed in the Philosophy in the Bedroom when Dolmance says “Modesty is an antiquated virtue.” (Sade 197) What is being expressed is an opinion that is terrifying; it lets the audience’s mind wander. What if Sade is right? How many virtues do I adhere to? Am I unhappy because of how I live my life or because of how others view my life?

Beauvoir goes on to suggest that one of the most terrifying aspects that de Sade brings out in his work is the idea of apartness or detachment. Each of his aggressive characters can engage in wild sexual exploits because they are detached from their victims. Their motivations are never explained other than it is constantly noted that they are libertines and libertines live for pleasure. Substitute pleasure for religion or politics and what would we call a libertine? Somebody who is willing to hurt and kill for deeply felt religious ideas and who is detached from their victims—is this not a succinct definition of a terrorist?

This is a term that I do not use lightly; I hearken back to the Latin root of the word Tererre: to terrify. So disconnected from the human victim is the Sadean hero that they are able to remain lucid and “so cerebral, that philosophic discourse, far from dampening his ardor, acts as an aphrodisiac.” (Beauvoir 21) Many authors use 120 Days of Sodom as the hallmark piece of Sadean literature, and it certainly is one of the longest and most obtuse pieces that he compiled. However, for the sake of understanding literary terror Philosophy of the Bedroom is a better example. It is nothing more than a long lucid, cerebral philosophical dialogue between characters while they engage in rape, murder and sexual violence. It is a handbook on how to be libertine and engage in libertinage without the slightest remorse for your victims.

For Sade like Burke and Lovecraft, pain is unmistakable and most often remembered; this is what it is to be sublime. Whether the pain is self-inflicted, inflicted by another or, more importantly in the case of de Sade, inflicted on another, pain is the keenest sensation. Dolmance, the most lubricious of libertines comments “Should it happen that the singularity of our organs, some bizarre feature in our construction, renders agreeable to us the sufferings of our fellows…who can doubt then, that we should incontestably prefer anguish in others, which entertains us, to that anguish’s absence.” (Sade 254)

While this may sound horrific (and to some degree it is) I categorize it as terror because it leaves so much to the imagination. The Sadean hero makes argument after argument for the abandonment of virtue, the taking up of vice, the need for murder and various other atrocities that the author says are perfectly natural. Sade challenges the reader to think through all of these arguments when they put down the book. The life of the libertine is not mindless, it is calculated and philosophically supported. Sade encourages the audience to become libertine enough that atrocities and horrors and all that which is filthiest and forbidden should rouse the intellect and prompt the reader into action, sexual and otherwise. No matter where one turns in the works of the Marquis they are not singularly confronted with over played and boring acts of violence. They are confronted by a philosophical call to action that is meant to persuade the mind while giving pleasure to the body.

Good and Evil

Lastly I would like to briefly devote some time to the notion of good and evil in de Sade. It is pretty characteristic of most societies to value the good and eschew the evil. This is a lesson we get from ancient thinkers, organized religion and even the most simple of ethical systems. It is the adherence to this rule that generally shapes the way one thinks and behaves in society. What we have seen with Sade is that the good is only what we make of it. If we can make the pain of others into our good we should take that opportunity and go with it. Further, he says that if we cannot always do evil and therefore be deprived of the pleasure that this brings, we should at the very least have the option to do no good (Sade 217). Again Sade casts the reader into uncertainty and obscurity (as Radcliffe says). We are perplexed just enough by his formulation that we are able to give it thought. This is terror, the ability to take a tradition of entrenched values and turn it on its head just for a little while. Enough time to make the audience stop and think and be just slightly confused.

Lastly I would like to briefly devote some time to the notion of good and evil in de Sade. It is pretty characteristic of most societies to value the good and eschew the evil. This is a lesson we get from ancient thinkers, organized religion and even the most simple of ethical systems. It is the adherence to this rule that generally shapes the way one thinks and behaves in society. What we have seen with Sade is that the good is only what we make of it. If we can make the pain of others into our good we should take that opportunity and go with it. Further, he says that if we cannot always do evil and therefore be deprived of the pleasure that this brings, we should at the very least have the option to do no good (Sade 217). Again Sade casts the reader into uncertainty and obscurity (as Radcliffe says). We are perplexed just enough by his formulation that we are able to give it thought. This is terror, the ability to take a tradition of entrenched values and turn it on its head just for a little while. Enough time to make the audience stop and think and be just slightly confused.

The Marquis de Sade has given the literary world many troubles. How do you classify him? Is he worth reading? Should we burn all his books and relegate him to the furthest reaches of memory? These questions continue to be a big part of Sadean scholarship. While de Sade is certainly gross and over the top most of the time, he also embodies the necessary attributes of literary terror. Being a precursor (and grandfather) of the gothic movement Sadean literature teaches the audience something about psychological terror. The constant rationalizing of counterintuitive morality opens the way for various forms of “uncommon” thinking that potentially could lead to action. While many will say these are just books written by a sick individual, such thinking does not further our understanding of terror. De Sade attempts to break the audience out of conventional modes of thinking and presents a different definition of terror that continues to haunt the psyche of those who have seriously contemplated his works.

Works Cited

Carroll, N. (1990). The Philosophy of Horror. Routledge: New York.

De Beauvoir, S. (1966). Must we Burn Sade? IN Wainhouse, A. and Seaver, R (Eds.). Marquis de Sade: The 120 Days of Sodom & Other writings. Grove Press: New York

De Sade, Marquis. (1795/1965). Philosophy in the Bedroom. IN Seaver, R. and Wainhouse, A. (Eds.). Marquis de Sade: Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom & Other Writings. Grove Press: New York.

Kaye, M. (Ed) (1985). Masterpieces of Terror and the Supernatural. Doubleday and Company: Garden City, New York.

King, S. (2010). Danse Macabre. Gallery Books: New York, New York.

Lovecraft, H. P. (2012). The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature. Hippocampus Press: New York.

Radcliffe, A. (1826/2004). On the Supernatural in Poetry. In David Sander (Ed.). Fantastic Literature: a Critical Reader. Praeger Publishers: Westport, CT.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

What amused me most is that Sade wanted to be remembered as a playwright, but his plays generally received poor response. He wrote much of his pornographic writing for money, and did so anonymously, denying he wrote several to his grave.

Prior to his thirties Sade was essentially just rich pervert who liked to party.

I’ve always held something of an eye-brow raising fascination of the entity that is the Marquise de Sade.

He is one of those historical personages that really seem like a character out of their own work. He is certainly fun to write about.

The original bad boy of the literary world!

Definitely! You have to be brave (or foolish) to publish the stuff that he did.

With Sade, it seemed (at least personally speaking) that the way he portrayed his own “literary terror” was more like foreplay for him; that he didn’t view its threat of torture and violence the same way as later commentators would now. But yes, stories like “120 Days of Sodom” or “Justine” could very well go either way in terms of their meaning since particularly with Justine, they could reflect Sade’s cynicism that following the chaste, morally pure path in life often makes you a target for deliberate corruption. So in that regard beyond the fatal fetishes categorized in his material, Sade is definitely fascinating for the many ways he can be interpreted (philosopher or pervert) and this article managed to convey both possible sides to the argument.

What a blazingly fantastic life!

Marquis de Sade is wildly unremarkable.

I would say I embody all of his best sociopathic, attention whoring, and belligerent misanthropy, but with none of the $, sex, and infamy. A genius indeed. An inspiration in my life, and hopefully yours as well.

The man was horrible, but so was most of his life. I’m not sure I have any friends who could stomach reading his books.

The word sadism comes from his name. Not sure if that is good?

I attempted to read his book Justine when I was in college. Wanted to see what all the fuss was about. UGH. I only got about 50 pages into it before I quit. The absolute loathing towards women dripped off the pages of the book. So disturbing. So venomous. So not how I want to spend precious hours of my life. It was like reading a snuff film. The complete antithesis of sexy.

I think Sade is the poster boy for creeps but at times I actually felt sorry for him.

Very turbulent times when he lived.

His sexual encounters were in fact not terribly different from many other aristocrats of the day (for the most part, and that’s not to say that most aristocrats’ behavior wasn’t reprehensible or kinky); he left his kinkiest ideas to his fiction.

Exactly! I think a lot of people assume that de Sade actually did what he wrote and that is just not true. He was making a point with his writing.

Sade actually wrote “non-explicit” works:

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donatien_Alphonse_Fran%C3%A7ois_de_Sade#.C5.92uvres_officielles

They are far more interesting than the sexual horrors of Juliette or the 120 days.

The novel Aline et Valcour, which Sade wrote under his own name, does not seem to have found an English translator.

No wonder – it is not intended to be sexually arousing and is a vigorous, though not outstanding, fictional vehicle for a critique of the France of the ancien régime and for the spinning of ideal alternatives deemed to exist in the South Seas. There were several such works produced in the France of the 18th-century, pre-revolution.

Diderot was much better at that sort of thing – try his Supplement to the Voyage of Bougainville, which is much less lengthy than Sade’s novel and much more beguiling. (The London Library, by the way, used stubbornly to file it under “Yachting”.)

The Church, the State, the Revolution.

Sade’s story (and the women in his life) is fascinating.

This is no glamorous or trendy view of sadism; our modern definition of the idea is pretty cuddly and fuzzy compared to Sade’s actual psyche and life.

Very well said. I think that with stories like 50 shades of gray we come close to Sadean literature but it is very watered down and weak. I am not saying this is bad, it has its reasons but as 21st century folk our ideas of sadism are generally lighter than the Marquis’

A good read – well written and engaging – but not for the weak of stomach.

a complex man for sure

I read the play Marat/Sade in college and saw the movie Quills so I knew Sade had been imprisoned in an insane asylum for his writings. That knowledge added to the creep factor of Sade.

I agree! I think that it both adds to the political intent as well as the creep factor!

As de Sade said in Justine: “Is there one religion not marked by imposture and stupidity? What do I see in all of them? Mysteries that insult reason, dogmas that go against the laws of nature, grotesque ceremonies that only inspire derision and disgust. But if one of them particularly merits our scorn and our hatred . . . isn’t it the barbarous Christendom into which we were both born? Is there a more odious one? Is there one which more offends the heart and the spirit?”

Whatever you say, but if I otherwise go to hell, I don’t mind very much to go against the laws of nature, to insult reason, to be hated, and to be barbarous.

Great article, fully detailed and thorough. Also a very enjoyable read about a classic, a book that has caused so much scandal at its publication that it continues to intrigue even today. I would recommend reading Dangerous Liaisons with it, a lot of similarities can be found between both works 🙂

interesting person. interesting relationships. interesting time in history

You wrote this lively and interesting which I liked!

Thank you! It is hard to keep the spirits up when you encounter some of his material.

The first thing I thought when I finished reading about the Marquis De Sade was, “He kinda reminds me of my father.” That can’t be a healthy response, can it?

Let it be known, Sade was a wrong’un.

I’m still scarred to this day from reading this horror. It was so exceedingly grotesque and vulgar, but it was made more-so by the fact that it was so beautifully written.

I can totally agree, once you have read him he tends to get under the skin

Sade books a quite an accurate representation of how deprive mankind can be without supervision and control.

Do we need a book to tell us this?

No!

It’s like saying torture porn slashers movies are art work exploring the limit of depravity.

Educational and inspiring?

No!

We all know mankind without control, or with the complicity of control can be boundlessly deprived.

He was a tormented genius but a genius nonetheless. His ‘Francais encore un effort pour etre republicain’ bit in ‘the philosophy in the bedroom’ is a master piece. You ought to read this bit at least, if not the the whole book.

Sade always punctuated is books with philosophical analysis/pauses. The question should therefore be; was Sade hiding political subversion under torture porn or was he hiding torture porn under political subversion?

Aesop /la Fontaine, Diderot, Rousseau he definitely wasn’t.

I personally have issues with people cultivating two persona/style so to use one to counterbalance the other, this includes presidents, other politicians, film directors and church leaders – very Marquis de Sade in fact..

Very psychopathic

He writes filth, but read the paragraphs about injustice and the abuse of authorities.

Maybe not today in the age of information, but in the 18th century it was necessary to hide political subversion in a more creative shell. He couldn’t exactly go on national television to reflect on the conduct of the aristocracy (ah wait, you can’t do that today either.)

Did anyone else read Justine as satire? I thought that he was attempting to create terror in his audience’s mind to demonstrate the horror he felt of society. I laughed at the description of the sister in the beginning of the book. If you pay attention, he very clearly set it up to be the opposite of societal expectations. All the terrible things that are done to Justine seem to be analogies for the terrible things society does to those who cannot conform.

What a pervert!

A spoiled, entitled, debauched aristocrat, an over the top epitome of 18th century France!

I like Clark’s definition of Terror as essentially being “about uncertainty and obscurity.” I’d add that another early distinction between Terror and Horror divides along gender lines, meaning that Ann Radcliffe was writing Terror, while Monk Lewis was creating Horror fiction. Of course, this makes de Sade, all the more intriguing, as by crossing gender lines, he finds another way to go against the prevailing mainstream views of his time.

Thank you for the read and the thoughtful comment, I really appreciate it.

De Sade’s name has become synonymous with sexual sadism even for those who have absolutely no idea of the content and context of de Sade’s work.

To dismiss his work simply because it is often horrifying is to give in to “antiquated virtue.” To read it for no other reason than the fact that it is horrifying isn’t any better.

Literature is constantly pushing boundaries, finding new ground, and challenging its readers to think. De Sade found undiscovered countries with his writing, not because of its grotesque aspects, but because it speaks to something deep inside all of us, something primal and terrifying, that many people don’t want to believe exists, much less acknowledge.

The terror/horror dichotomy is intriguing to me, and it’s interesting that my favorite “horror” writers seem to truly traffic in terror more than anything. For example, Thomas Ligotti largely eschews the visceral tropes of most horror fiction in favor of truly terrifying, cosmic-level despair. I think Ligotti, moreso than any other contemporary horror writer, depicts the sublime in a way that feels massive, insurmountable, and ultimately ineffable. Schopenhauer would be thrilled. THAT’S what I want from horror fiction, and I so rarely get it.

This is a great article! I really enjoyed and could easily digest how you distinguished “horror” from “terror,” and made clear connections between your claims and references. My only gripe is that I wanted to hear more. For example, you mention that his writing was during The Terror which, given the subject, I think could be another huge point in your article. Also, when you say, “When de Sade writes to his wife vehement that it is not the manner of his thinking but the manner of others thinking that has been his unhappiness we do not hear a man who is preoccupied with horror, what we hear is a man whose ideas cannot be expressed in the way that society would like them to be,” I think that connection could be made easily with “society,” because there were people who loved de Sade, and yet he was dismissed by the authorities. Anyway, I’m putting this on my FB.

Thanks for the great comment! I wish I could answer all of your questions but I think that would take another article! Who knows, maybe I will write another one on the Marquis. I am really glad you enjoyed it and you can always pm me if you have any questions/comments!

The is much to be said about what is “horror” and “terror.” This article is enticing and interesting. I enjoy the insight you gave on de Sade and hope you continue on the subject soon!!

*There*

I remember watching that Salo movie once. I swear it shocked me more than most horror films.

Horror vs terror is something I never think about. I have always used the two interchangeably. I’m fascinated with some of the opinions on both, specifically Radcliffe’s. The way terror is established makes me believe that terror is not necessarily “scary.” I think that is a trap that many audiences fall in to when they hear the two terms. I think it becomes a reaction to the situation and is more engaging. A characters life experience may not be grotesque but it might really shake the psyche of the audience. We don’t often want to engage with blood and gore and slashers. Radcliffe uses the word “freeze” when describing horror and that couldn’t be any more accurate.

I’m curious about what writers think when they tackle a project that may fall into this genre? Whichever medium and however the story is told. I’m also curious to know if horror sells more than terror? If we go off of the definitions listed in the essay, horror seems like something this current society would lick the clean off the plate. (Threw in a little horror myself, I think?)

I really enjoyed this essay! Thank you!

de Sade is certainly an interesting writer who captured man’s innate evil. In some ways he illustrates man’s sense of choice as the means to this evil, but rather views this as liberation from society’s brutal moral virtues, which are imposed upon people as much as man’s evil vices. Can people be blamed for fulfilling the ultimate gratification of their choices?

Sade’s work provides a fascinating insight into both the philosophy of horror and the workings of what many would consider to be a depraved mind. His far too often over-looked work should receive far greater recognition, particularly in view of relaxing societal views on BDSM. In spite of the slightly repetitive, the article makes excellent points.

I recommend the play Marat/Sade for any fans of the Marquis. I think it nails him.

Oh yeah, I read Justine and Philosophy in the Bedroom on my own in my senior year of high school. (As if it’d be assigned!) Definitely a writer who fascinates me. Also, I enjoyed that you brought Radcliffe’s horror vs. terror binary into the discussion. Excellent work!

The initial critical attention to Sade (speaking about !20 days of sodom) was mainly psychoanalytic, given the number of sexual acts which helped the sexologists to annotate it in the list of perversions, I liked how you speculated on the political philosophy of Sade as well as the affective feeling of horror and terror in his fiction.