The Monsters We Marry—The Weight of Percy Shelley On His Wife, Mary

What must be kept in mind when taking up the 1831 introduction to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is Shelley’s willingness to lie—“I have changed no portion of the story, nor introduced any new ideas or circumstances” (Mellor)—from here every conclusion we draw on what Mary Shelley puts forth must necessarily be kept a theory; nevertheless, we shall move forward as much as we can.

There are two major publications of Frankenstein—the first in 1818 and the second in 1831, after Mary’s husband, Percy, had died. I will not review the differences of each of the publications (though one might well argue that they are two entirely different books), but I will instead examine the differences of just the forewords to the two novels: the preface that appears in the 1818 text, in which Frankenstein was first seen in print, and the reintroduction of the novel, as Mary revised it, away from the influence of her husband, in 1831. The 1818 “Preface” was followed by the 1831 “Introduction,” and it is in these two short introductory pieces, when examined side by side, that we shall, when we lift the coverlet, find something perhaps sad, perhaps also not surprising: Mary wresting her identity away from what Percy had taken pains to create but in the end being unable. We might find, in fact, that Mary was, to some extent, Percy’s own experiment, in a difference of degree and not kind, as this experiment relates to the subject of Mary’s novel.

One important thing to note before we jump headlong in is that the 1818 preface was written not by Mary but by Percy acting as Mary (the reader would not have known), while the 1831 introduction was all Mary’s own. These two details are key to unlocking what may lie ahead.

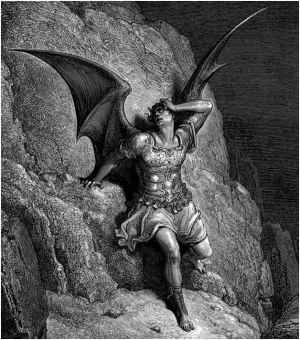

But let us begin many years before, with the preface to the 1818 publication, which was the first time Frankenstein appeared. Written, “[a]s far as [Mary Shelley] can recollect” entirely by Percy as Mary (“Introduction” 173), it plays right into the story about to unfold. There is the loyalty to the “elementary principles of human nature” (Frankenstein 5), with credit especially given to Paradise Lost; then a veiled reference to the storytelling competition challenged by Lord Byron in the rain and fog of the summer of 1816 in Geneva where the three were vacationing; and finally a dissociation from the “enervating effects” of novel writing and novel reading—this was to be a different kind of story, something which punched through the fabric of terror and the nature of man in order to find what terror man was capable of when he stepped into the role of creator.

Yet there are two striking subjects in the final three paragraphs of the 1818 preface: one is the notion of a “hero” who is never explicitly named. We are told, “The opinions which naturally spring from the character and situation of the hero are by no means to be conceived as existing always in my own conviction . . .” (6). We are, it seems, to view Victor Frankenstein as the hero of the tale, yet the interwoven narrative of Robert Walton interrupts such a clear “hero” to the novel. And so, if it could be stretched, does the creature himself, whose plight is given as the epigraph of the entire novel:

Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay

To mould me man? Did I solicit thee

From darkness to promote me?—

For those who recognize the source, it is of course from book X of Milton’s Paradise Lost, and the lines are spoken by God’s new creation, Adam, shortly after the fall. What are we to do with this information? Who is the intended hero of the novel? What is Mary asking or suggesting about creation itself, not just by man but by God? But not only who is the real “hero,” who the real “monster”?

Certainly, as the preface was written by Percy, and not Mary, we are taken back to Christopher Small’s argument, that Percy is Victor Frankenstein, or that Percy thinks he is, and that therefore Victor Frankenstein must be the hero of whom the writer of the novel (Mary) speaks. Of course Mary loved Percy, and his death was an untimely tragedy, but her masterpiece may be a commentary on the conceit typical of the human male. We love and despise our monsters, and we marry them nonetheless. Our love does not change their character, but neither does it prevent us from seeing it, at times in great debilitating flashes. And it may be that Percy’s ego is so distended that he cannot even recognize the subject that is being written in underhand about him—it is the monster’s greatest weakness—that he, Percy, has gone to the task of some creating and Mary’s identity has borne the fruit of it, with which she must now tussle. We will return to this creation in short time.

The second subject of importance comes from who is supposed to be Mary writing in her 1818 preface about the other ghost story competitors (Percy and Byron), “a tale from the pen of one of whom,” Mary allegedly writes, “would be far more acceptable to the public than anything I can ever hope to produce” (“Preface” 6). It may be nothing but polite self-effacement on Mary’s part, but of whom are we to think—Byron or Percy himself—as this other person? If, in fact, Percy actually wrote Mary’s preface, then this self-effacing sentence seems to penetrate and reduce Mary Shelley’s writing to rubble and to further build up Percy’s ego: “far more acceptable . . . than anything I can ever hope to produce.” What is Percy, in Mary’s voice, saying here about Mary? about himself? With this we shall move to the 1831 introduction.

Now it is thirteen years later; Percy has drowned; and Mary has taken pains to reintroduce and edit her famous novel. In the new introduction from 1831, Mary writes of her imagination, “a dearer pleasure,” “the formation of castles in the air” (“Introduction” 169), and how this world—the imaginative world—was hers, and hers alone. But also that this world was unable to surface in print: of novel writing, she says she “was a close imitator—rather doing as others had done, than putting down the suggestions of my own mind” (169); while, yet, “my dreams were all my own” (169). We begin to feel the force of the intrusive and scribbling Percy.

And even more of Percy’s harping: “My husband . . . was . . . very anxious that I should prove myself worthy of my parentage, and enrol [sic] myself on the page of fame” (170). If nothing more, it is worthwhile to examine the issues of gender and power in Mary’s introduction—a lot is being said. And whether or not the introduction remains truthful, it perhaps does not matter. Although we are inclined to take an introduction signed by the author as candid, it may not be; it may be yet another mode of fiction writing, of imaginative reification, where Mary felt free to express her world in her words and finally wrest these from Percy.

But near the end of the 1831 Introduction, Mary both credits and diminishes Percy’s impact:

At first I thought but of a few pages—of a short tale; but Shelley urged me to develope the idea at greater length. I certainly did not owe the suggestion of one incident, nor scarcely of one train of feeling, to my husband, and yet but for his incitement, it would never have taken the form in which it was presented to the world. (172)

This can be interpreted two different ways: the form of the 1818 text, as it was “presented to the world” was, as Anne Mellor argues, a version of Mary’s manuscript very influenced by Percy; and perhaps as Mary saw it, a very limiting one, which replaced her pure imaginative world with Percy’s acceptable version—and it is here when we pause and reflect upon Percy’s preface, and begin to be convinced that he is likely the “one” whose tales would be “far more acceptable”; that he, as Victor, is the “hero” of everything.

The other interpretation is that Mary is authentically crediting her husband with getting her to write the novel, no matter its final form—yet this, I hardly believe as the correct assumption, as we see in 1831, with her husband’s schooner now sunk, and his body now burned into air, Mary takes up the novel again and makes it hers, no matter how unappealing to us, by comparison, it may be.

Yet to be taken back to Mary’s room, a year after her death, to her unopened desk box and to find inside this little vault some remains pulled from the sea in 1822, now become dust—within a folded page of Percy’s “Adonais” and a few of his ashes, we see her love for him; what, one might imagine, would lie in Victor’s own vault of his precious monster had he outlived it. But would his creature have done the same, out of the hatred of being forced into existence in some particular image or other of which he did not approve come some love for his maker? To have unmade me might have been best, but out of raw material you created something, some lasting history, some genius. And here I am looking back at you now. Perhaps Mary would have thought this as she held the embers of his heart in her hand; perhaps she was, at least for some decades, Percy’s creation for himself.

We marry our monsters knowing full well what we are getting into. And we love and we hate them. They are destructive at times; they are filled with conceit; they are jagged and crude and expect a great deal from us. But they push us to our brink and out of what diminutive material we have to work with compared to theirs they bring forward the genius that we have. But of their genius, a whiff and we are undone; our knees buckle, and we collapse to the floor. A creative and destructive intoxication—the fruit which we can never resist—so seldom a creature is found. We would rather go under with them.

Perhaps it was this over which Mary grieved until her death. To be left alone for decades, the created bereft of her creator, unable to accept any other suitor; even declining marriage by replying to John Howard Payne that “after being married to one genius, she could only marry another” (Spark 110). There was to be no confusion as to her identity; it was no longer her own; and she did not mind. It had taken on another form, had been molded; she had been re-created from that Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin of old: “Mary Shelley,” she wrote to Edward John Trelawny, “shall be written on my tomb.” And that, it seems, to the uninitiated, is love.

Works Cited

Mellor, Anne K. “Choosing a Text of Frankenstein to Teach.” Frankenstein. Ed. J. Paul Hunter. New York: Norton, 1996. 160-166. Print.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein. Ed. J. Paul Hunter. New York: Norton, 1996. Print.

—. “Introduction to Frankenstein, Third Edition (1831).” Frankenstein. Ed. J. Paul Hunter. New York: Norton, 1996. 169-173. Print.

Spark, Muriel. Mary Shelley. London: Cardinal, 1987. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I read Frankenstein on and off throughout October and November and finally finished it early December. This was a rewarding read. Thank you.

My brain was knocked sideways by this relentlessly astonishing book. This was not what I expected.

This was a fascinating book, I imagine it must have been very disturbing in its day and found today the underlying message and question of creator, creation, life, human endeavor, and honor all have a place.

Fascinating viewpoint, it takes a refocussing of the book and is a tremendous interpretation

Very nice detailed work I appreciate your research. I also appreciate the role Mary Wollstonecraft played in addressing women’s rights.

This is a very bold fiction; and, did not the author, in a short Preface, make a kind of apology, I should almost pronounce it to be impious.

While Mary Shelley is a skilled writer, I have never been able to full grasp what she is trying to tell me, even in the illustrated children’s novel version, I still failed to understand.

Shelley’s work is much more than a gothic tale of terror; it’s a classic piece of literature.

The 1818 text is a masterpiece.

Here we have possibly the most famous gothic tale of them all – and without a doubt one of the very best.

I’ve never been able to truly dig Frankenstein. Not when I first approached the novel as a first-year English student. Not now, even though I’ve finally read through the 1818 edition of the text. I can appreciate the originality of Shelley’s concept. I can recognize her skill as a writer and the salience of her themes. But despite these attractions, I can’t quite move past a feeling distant admiration, rather than one of active engagement or passionate reverence.

Incredibly interesting read. I need to get around to reading Frankenstein, and thanks to this I won’t skip the foreword when I do!

I read both the 1818 version, and the 1831 version which she later edited, and would recommend the earlier version.

I love Shelley’s literary style. I love the ideas explored, the layers of questioning what a monster is and how it becomes such.

Nice thesis. This is an interesting tale filled drawn out in the elegant prose of the era in which it is written.

I’m having an inner conflict about who to feel sorry for.

Shelly’s grasping storytelling grasped me and possessed me.

I will be studying this book for my English degree and am grateful for this interpretation. I was hitherto concentrating on the influence of Mary Shelley’s father on the work

I love your interpretation, very interesting to read.

Full of depth and emotions one does not often see in today’s literature.

I’ve read Frankenstein and several fictional variations, but the one I found the most interesting is the book Angelmonster by Veronica Bennett. This fictional story details the relationship between Mary and Percy Shelley, and how the relationship essentially drove her to madness.

This is very intriguing, to look deeply at the work of Mary Shelley through how tangled her relationship with Percy was. I am glad to read so many details about their personal lives as they come into contact with the work – amazing to learn more about the Shelleys than one can see in just Frankenstein!

Engaging article and fascinating viewpoint that I have never thought about.

Okay first of all, I love this title. Fascinating how Mary in a sense uses the Frankenstein story not only as a sort of catharsis of her relationship woes, but also to comment on the Romantic movement as a whole.

This article is just brilliant. I’d read the 1818 ed. of Frankenstein many years after the compulsory high school reading of the 1831 ed. and have noticed how, as you say, these could very well be two different books, especially with regards to themes and moral economy. But I’d never in all this time known that the 1818 one was written by Percy Shelley!

Great title, but I feel like you left a lot unsaid in regards to her relationship with Percy, and frankly discredited Mary’s genius. I’m not sure where you felt this creature and creator bit came from.

This is depressing, but enlightening as well. I was reminded of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. Whatever the age, it’s a struggle for women writers.

I was somewhat familiar with this, but definitely not to the extent with which the article illuminates the issue. When I first read Frankenstein in high school, it was actually the preface/introduction that I found the most intriguing . . . even more so than the actual text (though I can’t remember what edition it was) since it’s pretty philosophical in tone. Nice examination of their marriage and its intertwining with the work they’re both associated with. Great title by the way!

I found this utterly fascinating. The Shelleys have always intrigued me, this has only fuelled that.

A good essay, interesting.