Using X-Men: Magneto Testament to Teach the Holocaust

Warning: This article contains some graphic information regarding the horrors of the Holocaust which might be disturbing to some.

How many Nazi concentration camps can you name off the top of your head? This is not a skill meant to impress your friends at cocktail parties. However, having a more complex and fuller knowledge of Holocaust history helps people of all different ages and backgrounds better understand the ways in which various systems and institutions failed in Europe, after the rise of Hitler, allowing ignorance, fear, and hatred to reign supreme, resulting in the deaths of millions of human beings.

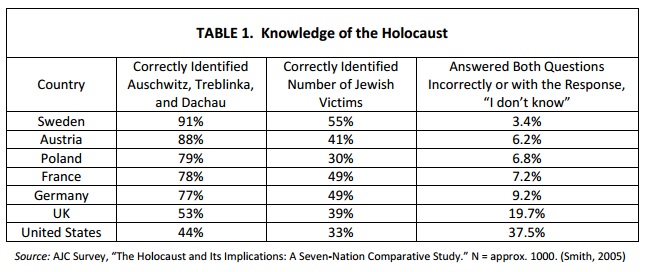

With all the educational resources available to American students and teachers, how is it that many Americans, when asked about the Holocaust, either don’t know much at all or can only recall general threads which conjure images of the ghettos, trains, and gas chambers and crematoria of Auschwitz? According to the chart above, Americans generally know much less about the Holocaust than our European counterparts. At face value, this gap is not surprising given the Holocaust happened in Europe; however, many might agree that the Holocaust is not just a Jewish or European tragedy, but a Human tragedy.

There are several challenges for teachers when tackling this heavy and large topic. First, there is that much of the circumstances discussed are more disturbing than most history topics while events and locations span across a decade and continent. Other challenges include the fact that the Jewish people, the largest group affected by the Holocaust, is a minority group in the United States and across the world. How are teachers at the middle school and high school levels supposed to condense something so horrible and monumental into a bearable and complete narrative? Also how can non-Jewish students relate to or feel emotionally invested in victims who are culturally different from themselves, especially when the number of victims is such a large statistic

Sometimes, fiction is the most effective way to spark a student’s interest in history. However, when it comes to the events of the Holocaust, historic fiction is still limited in that even a fictional character could not possibly have been present at and survive all key events such as the rise of Hitler, the ghettos, the firing squads of the Einsatzgruppen, the death camps, and the Auschwitz revolt. Unless, of course, that fictional character had superpowers. Therefore, Marvel’s compelling origin story of the villain/anti-hero Magneto, in the beautifully illustrated X-Men: Magneto Testament, solves many of the challenges that teachers face in presenting the Holocaust to students through its ability to include more events, a character which American audiences are familiar with, and Jewishness as a metaphor for any kind of Otherness. This study will challenge you to test your own knowledge of this history before presenting you with a brief, but more complete Holocuast narrative of events. Finally, in examining history next to Magneto’s origin story and publication history in the X-Men universe, one will be able to judge the educational value of this Marvel comic.

Test Your Knowledge:

Below are fourteen terms which are part of a more complete Holocaust narrative from the rise of Hitler to the end of the war. Before this article speaks to the benefits of including Magneto Testament as a supplement to history curriculum, I challenge the reader to tally up his or her score (feel free to leave it in the comments section) to gauge your own place in the context of this article. Otherwise, feel free to skip this section and move on to the rest of the article.

For each term, assign a number based on the following criteria:

“I have never heard this term” – Assign the number 1.

“I have heard this term but I am hazy on the details.” – Assign the number 2.

“I do know what this is as it pertains to the Holocaust, and can teach others about it.” – Assign the number 3.

Test your knowledge of these terms. No Google allowed.

1. Nuremberg Laws

2. The Madagascar Plan

3. Einsatzgruppen

4. Adolf Eichmann

5. The Wannsee Conference

6. Treblinka

7. Operation Reinhardt

8. “Selection”

9. “Angel of Death”

10. Auschwitz

11. Sonderkommando

12. Crematorium IV

13. The Warsaw Ghetto

14. Nuremberg Trials

When you have finished, add your numbers with 14 being the lowest score and 42 being the highest.

If you scored above 28, congratulations, you are a well versed citizen. If you scored below 28, you might benefit from reading Magneto Testament.

The Holocaust: A Complete Narrative

When modern Americans examine the Holocaust, many might be perplexed by its scope and the level of horrors involved. This leads one to wonder, “How did this happen?” or “How did this go so far?” One thing is certain: the Holocaust, as we know it, did not happen overnight. Some parts were carefully planned. Other components were improvised. Understanding a complete history of the events leading up to the mass extermination of the Jews and other groups in Europe helps to understand these questions and, more importantly, ensure that these events of history do not repeat themselves.

What would a complete narrative of the Holocaust look like? Many books and documentaries have tried to fit everything in as so many details are important. 1 I find that the strongest historiographies (studies of history and how the story gets constructed from the facts) begin with the Nuremberg Laws. The Nuremberg Laws were a series of restrictions placed on the Jewish people in Nazi Germany (and all Nazi owned territories) based on the ideal that the German Aryan race (the Volk) was superior and that other races were meant to sacrifice for the benefit of the Volk. 2 These laws are significant because in this situation, the persecution of the Jews was not only legal, it was supported and encouraged by the government: an extreme example of institutionalized racism. The goals of these laws were to ensure that the Volk profited from the economic exploitation of the Jews and to put pressure on the Jewish people to leave the German sphere of life.

For the Nazi party, the goal of the “Thousand Year Reich” did not just include purity of German blood, but purity of German culture. In this way, the very presence of the Jews in Germany was a problem, and many Germans wanted the Jews expelled. These tensions heightened after Hitler invaded Poland. With Germany involved in a world war, and propaganda perpetuating anti-Jewish stereotypes of vast, worldwide conspiracies against the German war effort, the expulsion of the Jews became a national security issue in the eyes of many German civilians. “What to do with the Jews?” became known as the “Jewish Question” and a man named Reinhard Heydrich and his secretary Adolf Eichmann were tasked with solving this “problem.”

Many “solutions” were suggested. Eichmann traveled to Palestine (at that time it was a British colony where many Jews from around the world had already peacefully settled) to report of the viability of sending Europe’s Jewish population there. This idea was discarded. 3 Another plan, the Madagascar Plan, was crafted by Eichmann and involved the Jewish population of Europe being sent to French owned Madagascar. After the Nazi conquest of France, this plan seemed possible; however, due to a lack of ships, it was also not a likely solution.

Around this time, Heydrich called high-ranking Nazi officers and officials to a conference, later known as the Wannsee Conference, to discuss plans for a “Final Solution of the Jewish Question.” 4 Eichmann’s policies of Emigration were replaced with plans for deportation of the Jews to the East that they may be used as slave labor in the newly conquered Soviet territories.

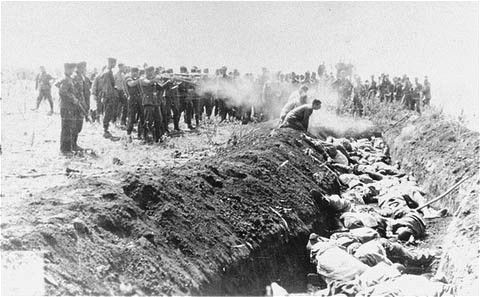

Deportations of Jews to Poland and other Eastern territories had already begun but with multiple German defeats in Russia, there was nowhere for the Jews to be sent. Ghettos, where the Jews were being held were now bursting at the seams. Special killing squads called the Einsatzgruppen were employed to lessen the burden of the increasing populations by overseeing mass killings. These killings were brutal, involving men, women, and children stripping naked and being shot into mass graves. 5 These scenes were so disturbing that even the Nazi soldiers carrying out their orders suffered great emotional and mental trauma from watching thousands of innocents die in front of them. The situation was becoming more desperate.

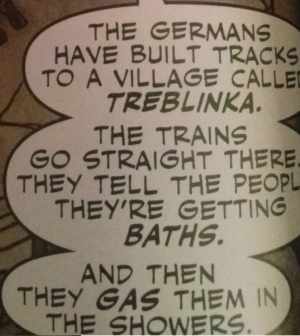

“Operation Reinhard” was put into effect. Three “death camps” were built at Treblinka, Sobibor, and Belzec so that the overflowing populations of the ghettos could be managed by killing more Jews. 6 These camps employed a different method of killing so that the Nazi soldiers would not be traumatized as they had been by the mass shootings: the gas chamber. This process, which used carbon monoxide from a tank’s exhaust pipe, was still brutal and sometimes took up to 30 minutes for the victims to die. It was not until a soldier in an obscure prison camp in Poland accidentally knocked himself out with the insecticide, Zyklon B, that a faster method of gassing was discovered. This obscure camp was called Auschwitz, and with this new discovery, a new huge camp named Auschwitz II or Auschwitz-Birkenau was built and became the largest killing center in the world.

Once prisoners arrived at Birkenau, they went through the process of “selection” on the train platform where Dr. Mengele, known as the “Angel of Death” would decide with one motion of his hand who lives and who gets sent to the gas chambers. Jewish men called the Sonderkommando were forced to escort men, women, and children to their deaths and burn the dead bodies in the many crematoria to spare the German soldiers from being traumatized as before. Towards the end of the war, there was a rebellion in which the Sonderkommando used smuggled dynamite to blow up the gas chamber at Crematorium IV. 7 There were similar rebellions in other camps such as Sobibor and an uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto. Nevertheless, the Holocaust claimed the lives of 17 million people. After the war, those Nazis who survived the war and who did not escape capture were put on trial for crimes against humanity in the Nuremberg Trials while others escaped justice.

Magneto Rising

Even after the war, many American knew little of the details of these atrocities. It was not until Adolf Eichmann was captured and put on trial in 1962 that Americans began to hear about what the Nazis had done as the testimony of many survivors was televised into American homes. The character Magneto appeared in X-Men comics a year later, although he was not confirmed as a Holocaust survivor until over a decade later. Under Chris Claremont’s direction, Magneto became a more complex super-villain as Claremont recalls, “I was trying to figure out what made Magneto tick… And I thought, what was the transfiguring event of our century that would tie in the super-concept of the X-Men as persecuted outcasts? It has to be the Holocaust.” 8

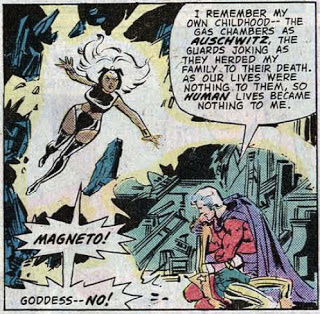

Magneto, known also by his alias “Magnus” or “Erik Lehnsherr,” was born Max Eisenhardt. 9 The details of his life as a Holocaust survivor has changed over the years as interest in the subject has increased since the mid-1970’s and more survivors have told their stories to the world. The first mention of Magneto’s Holocaust origin seen in the photo to the left from Uncanny X-Men #150 (1981) was generalized and basic; much like America’s knowledge of the Holocaust at that time. As simple as this origin is, it still reflects the way Civil Rights leaders would use the Holocaust as a warning against what can happen when certain groups of people are marginalized.

“We can never forget that everything Hitler did in Germany was ‘legal'” -Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Letter From Birmingham Jail, 1963

Uncanny X-Men #150 was also published in a time when media portrayals of “Americans” were becoming less white-washed and more willing to face the darker aspects of human history. The unprecedented success of the TV miniseries Roots in the late 1970’s showed that Americans were ready to accept a transplanted African lead character as an “American” hero. Oftentimes, Magneto’s reinvention as a Holocaust survivor is attributed to the popularity of the TV miniseries Holocaust which is said to have been made because the success of Roots paved the way for American reception of stories about ethnic oppression. Throughout the 1980’s Magneto’s mentions of the Holocaust fell under the same form: mentions of how the mutants and the Jews were similarly persecuted. The details are still simple: he was imprisoned in Auschwitz, his family murdered, he meets the Gypsy woman Magda, and they escape together towards the end of the war.

Towards the late 1980’s and early 90’s, more and more survivors openly told their stories due to a growing interest in the subject and new films such as Sohpie’s Choice (1982) and War and Remembrance (1988). With more details surfacing about the horrors of Auschwitz, a 1991 issue of X-Men nuanced Magneto’s past and it is revealed that during his time in Auschwitz, he was a member of the Sonderkommando. He says, “I should have died myself, with those I loved. Instead I carted the bodies by the hundreds by the thousands … from the death house to the crematorium … and the ashes to the burial ground. Asking now what I could not then– why was I spared?!” 10 This portrayal of Magneto is a far cry from the one-dimensional super-villain of the 1960’s. Not only is his need for revenge not present, neither is his self-defensive action. This Magneto is defined more by survivor guilt and post-traumatic stress disorder. Not only is his history of Holocaust survival becoming more detailed, so is his psychological profile.

Movies like Schindler’s List then set the standard for how stories about the Holocaust should be told. Now it is not enough to simply tell a story, it must be accurate, informative, as complete as possible, and compelling. The fact that the 2000 movie X-men opens with a young Magneto’s arrival at Auschwitz is significant because the makers of the film chose to establish the central conflict of the franchise through Magneto’s Holocaust experience as a warning of what could potentially happen to mutants in their persecution escalates. All of a sudden, Magneto’s story defines the struggle of all mutants, and the mutant’s struggle defines the struggle of anyone who is outcast because of race, gender, sexual orientation, etc. In 2008, therefore, it was time for Marvel to create a narrative for Magneto which was historically accurate, informative, complete, and compelling. The result, X-Men: Magneto Testament, was not just one of the best developed Magneto stories, but one of the best developed Holocaust-related historical fictions.

The Story of Max Eisenhardt

Part of what makes a real-life story like The Diary of Anne Frank compelling is the fact that it is a coming of age story which follows the timeline of events in WWII. In making X-Men: Magneto Testament, the creators, led by Greg Pak, had the difficult task of creating, not just a coming of age story, but a super-villain origin story which stood up to history and Marvel cannon. In order to create a more complete timeline, the authors decided to make Magneto of German-Jewish origin (instead of Polish-Jewish origin as he had been previously written) so they could cover more information on the rise of Hitler.

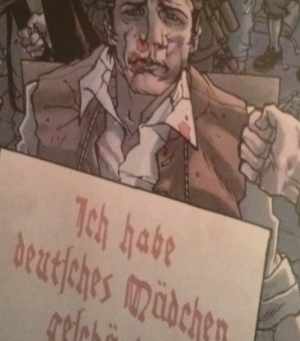

Max’s story begins close to where Anne Frank’s story begins: with the passing of the Nuremberg Laws. Where Anne details in retrospect how her civil rights were slowly taken away, Max witnesses his uncle Erik (a possible inspiration for his future alias) being dragged through the streets for having relations with an Aryan woman. Slowly but surely, Max and his family lose their rights but do not leave the country on the assumption that things can’t get worse.

Because the story focuses on Jewish characters, there is not mention of things like the Wannsee Conference or the Madagascar Plan as these were things that the public were not aware of at the time. However, the effects of these things are present in the fact that Max’s family emigrates to Poland where they become trapped after the Nazi invasion. They are placed in the Warsaw Ghetto which is accurately presented as overpopulated. The effects of Operation Reinhardt are seen as people in the Ghetto are tricked into boarding trains to Treblinka where it is revealed they will be killed.

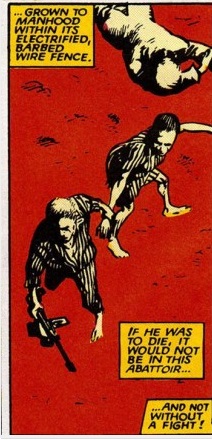

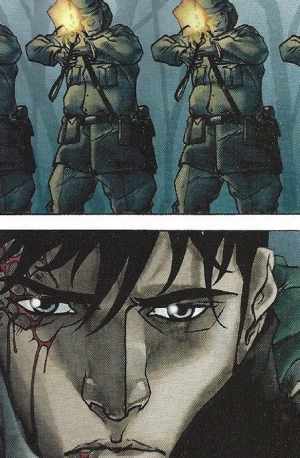

After a daring escape from the Ghetto, Max’s family is betrayed and captured by the Einsatzgruppen who shoots and kills Max’s family. The writers decided that Max should not be aware of his powers throughout the course of this story. Therefore, the fact that Max unknowingly bends the Nazi bullets in another direction can also be interpreted as Max’s father pushing him out of the way. However, to those who are familiar with Magneto, the hint is strong enough that Max survives this episode because he has superpowers.

After escaping the mass grave that his family is buried in, Max is arrested once more and sent to Auschwitz. Upon his arrival he is told to lie about his age to survive the Selection process. Dr. Mengele spares his life and through a series of unfortunate events, Max finds himself a member of the Sonderkommando. As a member of this group he witnesses horrors beyond belief and is part of the Sonderkommando revolt, allowing for his escape with Magda. Great pains were taken to ensure that the story was as accurate to history as Magneto’s lore.

In this way, Magneto’s story and a more complete Holocaust narrative have been consolidated in one book which is accompanied by a teacher’s guide for any teacher who wishes to use the comic to supplement other academic exercises.

The Nail That Sticks Up

Finally, the most compelling aspect of Magneto Testament is the fact that Max’s difference, embodied by his Jewishness, is used as a metaphor for anyone who feels different or out of place. This allows American readers of all different backgrounds to identify with Max and echoes the way in which Civil Rights leaders used the Holocaust in their messages. This message of solidarity is presented in the words of Max’s teacher: “The nail that sticks up, gets hammered down.” Through this lesson, any reader who is “different” understands how difficult it can be to stand out from the crowd. Nevertheless, part of what makes the X-Men franchise so popular is that while it is honest about the hardships of Otherness, it encourages non-conformity and dreams of a world where those who are different can live freely.

Max remains an “American” kind of hero despite his hardships. Before his family is killed, he is optimistically rebellious against his oppressors. He is smart and savvy in Auschwitz and after he is broken as a member of the Sonderkommando, it is his love for Magda which drives him to survive and join the Crematorium IV Rebellion. For American readers, these values which he embodies make his story compelling. While reading this comic, written in a style of English which is inherently American casual, the Holocaust does not seem so much like a black and white picture in a history textbook of something that happened “a long time ago” in a place “far away” to a people “not like us.”

Hopefully after reading this article, you can score higher on the Test Your Knowledge list in the first section. Hopefully you have been inspired to further your own knowledge and use the events of the past as a tool for progress in the future. While Magneto, as a villain, uses the words “Never again” to justify violence against those who would harm his people, the best lesson to take away from his tragic story is that the only way to prevent persecution of those who are different is through education.

Works Cited

- The information in this section comes from Roseman, Mark. The Wannsee Conference and the Final Solution. New York: Picador. 2002. unless otherwise specified by a footnote. I have also included names of films which include some of these events. ↩

- Koonz, Claudia. The Nazi Conscience. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 2003. ↩

- Mallman, Klaus-Michael. Nazi Palestine: The Plans for the Extermination of the Jews in Palestine. New York: Enigma Books. 2005. pg., 54. ↩

- This conference is portrayed in the HBO film Conspiracy for those who are interested. ↩

- One of the most accurate portrayals of these events in film is the 1988 miniseries War and Remembrance. It is also briefly alluded to in the film Defiance. ↩

- This period is included in the film The Pianist and the made-for-TV movie Escape From Sobibor ↩

- One of the few films which focus solely on the Sonderkommando is the movie Gray Zone (2001) ↩

- Malcom, Cheryl Alexander. “Witness, Trauma, and Remembrance: Holocaust Representations in X-Men Comics.” The Jewish Graphic Novel: Critical Approaches. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. 2008. pg., 144. ↩

- X-Men Vol 2 #72 reveals that “Erik Lensherr” is an alias ↩

- Vol. 1, No. 274, March 1991: 11 ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I actually like the idea of teaching through comics. I actually have a bunch of manga math books! I think it does make it more personal and interesting.

The X-Men were always socially aware and preached about civil rights equality for all.

I like the new Thor, Cap, Ms. Marvel, and Miles as Spidey. But there’s some things that need to stay the same. Magneto being a Holocaust survivor is one and the other to me is Cap fighting in World War II and growing up during the depression (something Marvel doesn’t do enough with). Those are two things that are very much a part of the characters and should be changed. Stark being injured in Korea, Vietnam, Gulf War, or Afghanistan doesn’t change the character much, but remove those elements from those two characters and you have a very different character.

This is an excellent piece of work: sharp and reflective.

Why should comics not be allowed to root its narrative in real life tragedies such as the Holocaust? Great content by Marvel as every.

The issue with superhero comics is that the conventions they trade in can only really handle the experiences of real-world mass death as metaphors. I had no problem in seeing the post-apocalyptic landscape in X-Men: Days of Future Past. It is a work of fiction, and Bryan Singer and his team have a right to create their own scenarios.

The problem with the Holocaust is that it is not a fictional scenario. It is a very real enormous thing that no one has any real ability to absorb and our contemporary culture, more often than not, speaks about it a little too casually. I’m as guilty of this as anyone. I like superhero comics, but by placing Auschwitz in the middle of a narrative in which we’re also supposed to admire beautiful bodies and enjoy adventure…well I think you can see the issue.

Thank you for your input. I suggest that you give Magneto Testament a read, however. It does anything BUT trivialize the historic events contained therin. As my article highlights, there have been instances of Magneto’s past being portayed in a superficial fashion. This is a grievance which MT sets out to remedy and does so sucessfully with pages and pages of citations to back up the events of the plot and provide material and sources for further reading on the subject. That being said, while MT is beautifully illustrated, it does not glorify the horrors of the Holocaust in any way. I jave chosen to exclude some of the more graphic moments in the book. I suggest you give my article another read and give MT a chance. You may be pleasantly suprised.

I agree somewhat, but that would make me a hypocrite. I think Watchmen is an excellent comic, even though it uses the horrors of the Vietnam War. Maybe Alan Moore’s politics are so close to mine that I can forgive him.

Any artist who directly uses such a horrific historical event has a responsibility to make sure the event retains its meaning.

I agree, though with this particular event it is often difficult to find “meaning” or even assign “meaning.” The best one can do is present the most complete narrative possible.

I agree with your about how depicting historical atrocities demands a high level of responsibility from the artist.

Magneto is one of Marvel’s most important and sophisticated characters.

He remains one of the best adversaries in comic book history precisely because of his Holocaust and World War II backstory.

We can never sit back and ever let anything like this happen again.

The first time I answered looked at the fourteen terms in the article above and ranked them, I got a 22. After reading the article all the way through, I went back and came away with a score of 38. Your article is an amazing, interesting, and skillfully crafted piece of work. I love comic heroes and villains and their stories, and Magneto has always been one of the coolest and most sympathetic and intriguing villains/anti-heroes to me. You can rest assured I will get my hands on a copy of “X-Men: Magneto Testament” as soon as possible. I really want to read this story. Thank you for educating me on this topic. This is the best thing I’ve read about the Holocaust since Eli Weisel’s “Night”.

Thank you. I am truly humbled.

My son picked this up from the library recently. After reading this article, I will have this on my reading table tomorrow.

For me, fiction about Nazi Germany is somehow harder to read than non-fiction. With fiction, you see events through the eyes of a protaganist, bringing you uncomfortably closer to their emotions.

Love reading this book.

I’m a little conflicted about this. This was a really well-executed story of the Holocaust and what it meant to just survive those times as a Jewish boy. I’m not sure it’s the Magneto I care about, which is where the conflict comes in. One of the things I enjoy about Magneto is his deep wellspring of rage at humans and how they have fucked up. On occasion, his argument about why a minority should rise up and take their rights rather than peacefully work towards them. There is no rage here, despite all the tragedy Max goes through. While reading the story, I attributed this to Max being in shock, but at least in the last panel, I would have expected some justifiable rage.

Testament is one of the best origin stories I’ve read.

This is actually shockingly done with such accuracy and respect to the actual events of the Holocaust. You gave this article the same treatment. Thank you.

I wasn’t feeling the impact it should have given me. I had the same problem with Alan Moore’s V FOR VENDETTA.

Made me cringe several times when reading this.

Intriguing. By placing historic cases of genocide in a fictional context, we are giving ourselves the psychological support that we need to look at such atrocities…? In other words, maybe as a society we have to look at events like the Holocaust indirectly because it is too horrific to look at directly? Isn’t it better to look at it indirectly than not to look at it at all?

Have you seen a documentary called Room 237? It is all about Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining and the various cultural and social substrata that exists in that film, the Holocaust chief among them. In the documentary, a commentator posits at one point that Kubrick always wanted to do a film on the Holocaust but never could bring himself to deal with it directly, given the unfathomable nature of it. Thus, according to this individual, Kubrick chose to deal with it indirectly in the form of The Shining. I thought that to be pretty insightful.

Marvel should not resort to pandering. The past is the past. The Holocaust happened, to not want to acknowledge it is foolish.

I enjoyed this article and learned more than I expected.

This was a fantastic article. The X-Men franchise has intellectual commentary on both discrimination of race and sexual identity and, as you said, the horrors of the Holocaust. Anyone can relate to why Magneto has such a hatred for humanity, and that he is one of the profound characters in comics.

From reading this article I now wonder why Wolverine’s origin story was made into a movie and Magneto’s hasn’t been…

I’m also embarrassed at how little I knew about the holocaust. I got a 17 on the test, and I call myself a history buff. If you’ll excuse me I’m gonna go get a band-aid for my pride.

The weird thing though, is that I don’t remember learning about most of this stuff in school. I don’t mean “I learned this but then I forgot and now I remember talking about it at some point” I mean I don’t remember these things being mentioned, ever. I suppose I could have just forgotten completely, but I can’t help but wonder if it was being purposefully cut out for some reason…

I learned most of this information after college while writing a play about the Wannsee Conference. Once I started the project I relaized how little I knew from my high school and college education (and I was a history major). The “complete narrative” above is the product of five years of research, which no one should have to do to find this kind of information. So when I find easy-to-read books on the subject I want to spread the word. I think that the main reasons you didnt learn a lot of this in high school is for the reasoms highlighted in my introduction.

I picked this up because I love Magneto and I’m a history teacher. I finished it in an evening and I became a true Magneto fan. I was also overjoyed to discover that it had been meticulously researched and also provided liner notes and a lesson plan in how to integrate this book into the curriculum.

Thank you for your comment. I am so glad to hear from a teacher.

It’s obvious that Greg Pak cared a lot about presenting an accurate Holocaust narrative.

A valuable history lesson about the depths of the evil of which we are capable under the worst of circumstances.

I think that in order to fully appreciate this book you need to look at it as a Holocaust book, and not a comic book.

I really like the great extra comic at the end about a real Holocaust survivor, that brings the whole thing home even more.

He seems a hell of a lot more sympathetic now and I want to know more about what he chose to do with the knowledge of what humanity is capable of.

He’s my favorite villain in all of fictional media.

Magneto’s story is heartbreaking–as it should be.

No one should have to suffer due to a bunch of narrow minded individuals such as The Nazis and their Ilk.

This could serve as a standalone Holocaust story because you really don’t need to know anything about the Xmen character.

This is one of the best origins I have ever read for a comic book character.

For anyone interested in a graphic novel about the Holocaust, it doesn’t get better than this.

The Holocaust element serves mainly as exposition for Magneto’s character.

Interesting article – thanks!

A great book to us as supplemental material to teach young children about the Holocaust.

Interesting topic.

One of my favorite GNs. A very emotional and gripping tale of courage and dignity.

Thanks for the article.

The idea of using comic books as an educational platform was (and continues to be) amazing in the sense that it makes history feel relatable and interesting. Magneto has always been one of my favourite villains, as well as one of my favourite X-Men articles. Loved the article. Great job.

Beautiful and perfect! This articles simultaneously makes me want to run out and read the comic as well as use the materials for any educational purpose.

Thank you for inspiring me to keep promoting Holocaust education. I learned so much from this article. Hope to see more of your work.

I don’t feel any sickening horror when I read Magneto: Testament. That’s a problem.

Kudos on this piece of writing.

I certainly think our culture is far too inundated with banality that when it treats somber subjects like the Holocaust in its literature, it runs the risk of sentimentality or flippancy. But the Testament works well, just how you have details in your article.

Really amazing article. I feel more educated about the holocaust and this was a good read.

Good stuff!

This has got to be the best and most useful article i’ve seen in just about forever.

I always love it when comics or Science Fiction decides to throw in things such as history and mythology that not only teach you, but encourages people to further research the topic in a way a person usually would never do.

The fact that you made the article so very interactive only adds to the amount of interest readers will feel in reading this article. Personally I enjoyed the area where you ask people if thy know the definitions to certain terms as it encourages people to go beyond simply reading the article but experiencing it!

I’m glad you enjoyed it!

I think that this article perfectly demonstrates why Magneto’s Holocaust origins are integral to the character.

I definitely need to get my hands on this comic now. It’s such a crucial topic, and one that needs addressing.

Sharp, well written, and informative article.

Great article. I haven’t read Magneto Testament, and admittedly hadn’t heard of it until now. One of the most interesting aspects of Magneto’s tragic back story, certainly the most troubling aspect, is that it isn’t quite enough to read him as a victim. Magneto is an embodied comment on evil’s capacity to beget evil, the possibility for the rise out of adversity to turn to extremism. An obvious parallel is Magneto as an amplification of pre-Mecca Malcolm X at his angriest, against Xavier’s Dr. King. I’d be curious to hear Stan Lee’s reaction to some of the possible, and no doubt controversial, readings that come to mind to associate this character arc with certain contemporary political discussions.

Nicely done! Well written and informative. Can honestly say I learned some history here. I never knew about the Sonderkommando.

Very intriguing how you combined such a historical tragedy and comics. And not only combined the ideas and drew similarities, but also made it relevant by expressing the United States apparent lack of knowledge in such an area.

Great text and I appreciate Mandracchia’s treatment of it in the article. One thing I’d like to add is that comics scholars have been identifying the X-Men as diverse representatives of humanity in the civil rights era and since. Those same scholars have been in a contentious spot, either advocating the medium as subversive or lauding the popular and transmedia appeal. This contentiousness explodes when the discussion turns to using comics pedagogically. When Karma comments, “I think that in order to fully appreciate this book you need to look at it as a Holocaust book, and not a comic book,” for instance, implicit is the idea that comics are juvenile, vacuous, purely entertainment vessels (i.e., a Holocaust book would be *serious,* by comparison). Or consider the stigma of the popular comic that comics can be read and understood in a snap (i.e., expressed simply by Helen: “I picked this up because I love Magneto and I’m a history teacher. I finished it in an evening and I became a true Magneto fan. I was also overjoyed to discover that it had been meticulously researched and also provided liner notes and a lesson plan in how to integrate this book into the curriculum.”).

Belt comments that “The issue with superhero comics is that the conventions they trade in can only really handle the experiences of real-world mass death as metaphors,” and for comics scholars, that shows a narrow understanding of comics. But Belt’s point is taken. Again, comics are broadly understood, and have been in the US for 60 years, as simple, entertaining texts for kids (e.g., that’s why Crumb and *Watchmen* upset everyone). At the same time, Riley, commenting more expansively about all writing about the Holocaust, writes that such work “runs the risk of sentimentality or flippancy.” Again, in the hands of many teachers and education scholars, *Magneto Testament* is a high-interest text (ahem, tool) that will up students’ motivation to engage the curriculum (e.g., in this case, secondary history and social studies about WWII). Flippant texts or not, cultural critics pair with teachers who are lamenting the twitter-blasts of content, and have instituted programs like “silent sustained reading” to address the issue of habituation of the practice and depth of reading (long texts).

Mandracchia’s article is smart and a thoughtful plan for engaging contemporary Gen Z students. The more fundamental question, while Rome burns and pre-9/11 and often pre-Google US teachers teach post-9/11 students, is one of literacy.

Magneto has always been a favorite of mine. He’s so much deeper than the average character. He has been through so much. And lately, he has changed and become a hero, which I’m excited about because I can finally root for him. Great article.

It’s always been interesting, that the most known X-Men antagonist has had the most tragic backstory. The opening to the first film of X-Men got it right with that. It is only in overreaction and cost to innocents that Magneto is wrong.

My literature teacher a long time back, used to to this kind of thing. To teach us about the Soviet Union we read Animal Farm. To learn about the Holocaust we read The Boy in the Striped Pajamas and The Wave. She wanted us to understand key events in the world through books and I really respect how you’ve done the same thing with this article. Thank you so much for writing this.

“using x-men: magneto to teach ABOUT the holocaust”

*slow clap.

Meanwhile I hope you paid more attention to learning ABOUT the Holocaust in this article instead of the grammar of the title – which is not incorrect. 🙂

Comics are a great way to learn tragedy. I think the problem with the Holocaust is predominantly a proximity issue (as in, despite America being part of the War it never actually reached its shores). Also, the sheer complexity and devastation of human life. Most people struggle with small, personal deaths let alone mass, methodological, killing. Even with the complexity of Holocaust history, this was a great way to dive into the material and start understanding. Well done!

One observation as to why Holocaust knowledge is higher in Europe: the students that are in secondary education actually visit the locations where important moments in the Holocaust occurred.