Penderecki and the Sound of Horror

Over a century of horror movies has made for a plethora of horror villains — haunted houses, zombies, monsters, the evil acts committed against one another — or a number of unseen forces whose consequences and effects give the film its raw immaterial fear. Even with the variety of manifestations of horror over its lifespan in film, one characteristic of horror has been consistent throughout: the element of sound that is crucial to the horror experience.

Ever since the inclusion of sound in film the unsung villains of horror movies have been their crawling and ominous scores and soundscapes. Where would the classics of the proliferating genre, or the overall atmosphere we come to expect in horror be without the innovative sound design and composition techniques of Bernard Herrmann, Krzysztof Penderecki, and John Williams? (to name a few.)

In King Kong (1933) we see the first OST, or original soundtrack written for an American “talkie” according to Sound Field (PBS), which was only slightly after the first feature film presented as a talkie which was 1927’s The Jazz Singer. The talkies, or talking pictures, were the first sound films to include synchronized dialogue. Before that sound films would include only accompanying music or recorded dramatic effects.

The first horror film was a French short — just over three minutes long which translates to 60 meter of film — called Le Manoir du diable, or The House of the Devil. This was released in 1896. The film was discovered in the New Zealand Film Archive in 1988 after presumably being lost. The music that plays over the short film has a minimalist tendency that gives it an ominous feel reminiscent of a spinning ballerina music box. Eventually this tin sound is accompanied by a chorus of vocalists.

Part of the creepiness of the music is also its modal quality and by this I mean its key signature in relation to the mode of the major scale that is being played. The song centers around a Lydian scale, the 4th mode of the major scale which contains an augmented fourth, or a tritone. Otherwise known as the devil’s interval, this famous interval has a history of avoidance due to its dissonant sound which was largely interpreted as a manifestation of evil.

Why this perceived interplay between diabolic forces and music? This is a huge question which spans areas from tonal theory to human physiology, but for our purposes we will just say the relationship between fear and the ear is not entirely new.

‘The world of the ear is more embracing and inclusive than that of the eye can ever be. The ear is hypersensitive. The eye is cool and detached. The ear turns man over to universal panic while the eye, extended by literacy and mechanical time, leaves some gaps and some islands free from the unremitting acoustic pressure and reverberation.’

This is a quote from Canadian media guru and philosopher, Marshall McLuhan (from an essay called ‘Clocks’ in Understanding Media: Extensions of Man, 1964). McLuhan touches on what is central to the experience of modern horror: though we can be afraid of what we see on screen, a massive part of the medium is the characteristic and unrelenting sounds of horror. Sound forms the very atmosphere of what horror has become. This is true from building and atmospheric suspense to the widely-used jump scare.

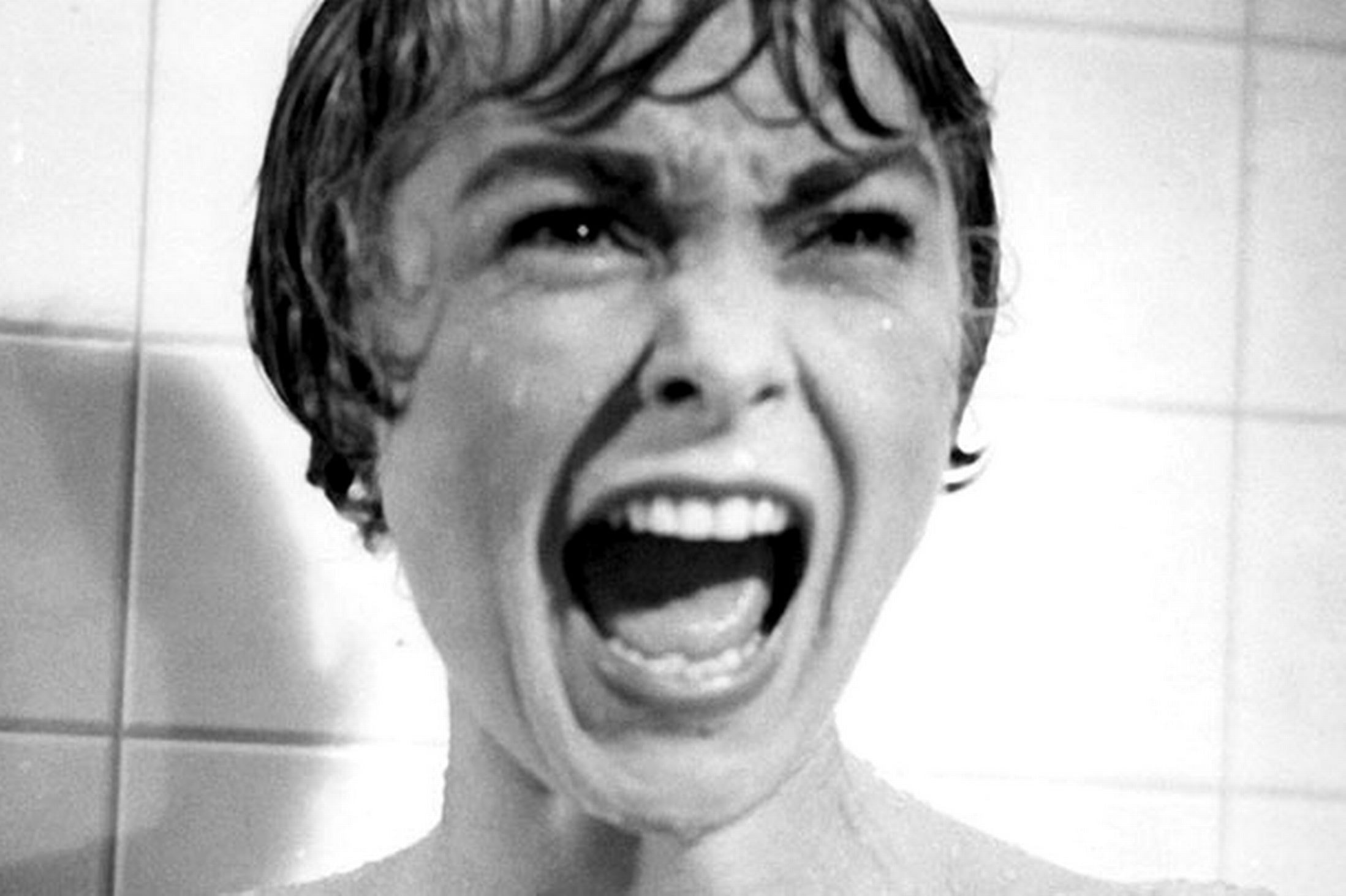

An early example of the jump scare is also one of the most famous examples of what is called a ‘stinger chord’: sharp, screeching notes played by shifting on the fretting hand on the strings to give a stabbing or stinging effect. This was in one of the most famous scenes in horror film history, Alfred Hitchcock’s classic shower scene in Psycho (1960). This example of a stinger chord by Bernard Herrmann, the composer responsible for the music of Psycho, is one of the foundations of characteristic sounds in horror film.

Later composers and music directors began to make use of innovative sound design techniques as much as they would select and write music for the screen. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) made use of animal noises to set the stage but also has another terrifying sound effect that preserved its effect all the way up until the 2004 remake. This effect was created by ringing a tuning fork before rubbing it along a piano string to bring out unsettling overtones for a brief moment.

Consider as another example the iconic whisper sound effect in the Friday the 13th film series. Composer Harry Manfredini shortens the words ‘kill’ and ‘mommy’ into the characteristic ‘ki-ki-ki-ma-ma-ma’ and sets audiences’ hair on edge. This short auditory effect is as memorable as any moment in virtually any of the Friday the 13th movies. It becomes part of the lexicon of the sound of horror. Building on previous techniques, the Friday the 13th movies are also chock-full of stinger chords to accentuate jump scares.

Then there is the association of playing a low E and F in sequence that is inseparable from the terror felt in Jaws (1975) thanks to prolific composer John Williams.

We also have John Carpenter’s strangely simplistic but creepy musical piece in 10/8 time in Halloween (1978). Carpenter attributes one of his major influences for the original score to William Friedkin’s soundtrack in The Exorcist (1973), in particular Friedkin’s use of part one of Mike Oldfield’s ‘Tubular Bells’, the track most commonly associated with the film. The influence of the minimalist style can also be heard, with new instrumentation, in the music of George R. Romero’s Day of the Dead (1985) and music by John Harrison.

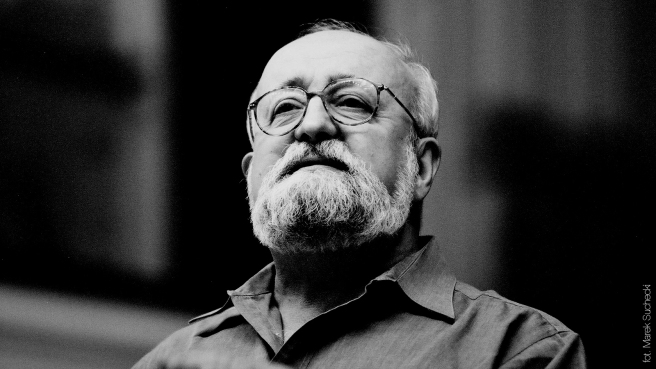

Another massively influential piece of music included in The Exorcist is a piece by Polish composer and conductor, Krzysztof Penderecki which according to Sound Field (PBS) changed the sound of horror music forever.

Penderecki was at the cutting edge of experimental or avant garde composition. “All I’m interested in is liberating all sound beyond tradition,” he said. With this attitude, Penderecki composed disturbing compositions bereft of traditional tonal movements or rhythmic form.

Instead his compositions consisted of what are called sound masses, or large clusters of tones which form an eerie lack of centrality, in which individual pitches are de-emphasized. There are no key signatures, cadences, or any traditional elements associated with the orchestra; there are subtly moving to chaotic sound masses which build in volume and unpredictability giving an absolutely unsettling feeling all too familiar to horror fans and accentuating the horror on screen. In this way Penderecki revolutionized the means of embodying anxiety through sound.

In 1973, Penderecki’s ‘Polymorphia’ is used by director William Friedkin in The Exorcist (and later by Stanley Kubrick in The Shining (1980) which also contained five of his other pieces). Famously, The Exorcist shocked audiences to the point of being vomit-inducing. This is in part because of the disturbing use of cutting-edge onscreen effects and the experimental soundscapes of Penderecki.

In a very real way, Penderecki’s sound masses in compositions like ‘Polymorphia’ represent a pinnacle of terror embodied in sound. The chaotic sound of Penderecki’s composition becomes characteristic of subsequent horror soundtracks and his influence can be heard to this day in any number of horror films.

With new use of techniques including extensive use of compression, limiting, and the like, new sound design methods ushered in by a new era of digital audio production in film as well as in popular music. Audiophiles have a love/hate relationship with this. But new technologies can also be used to throwback to a prior time. Homage to an earlier era of the sound of 80’s horror can be heard in Netflix’s thriller series Stranger Things, and the recent classic It Follows (2014). It Follows does an excellent job of making use of the Penderecki-style sound masses as well as the later synth-based melancholia creating the ambiance of an 80’s classic in the modern era. These days low frequency effects — often near the lower range of human hearing just audible enough to disturb us — and similar digital techniques are more widely heard while the immortal style of Penderecki lives on.

As everyone knows, it is often what we do not see on screen as much as what we do that builds terror and fear. The ultimate unseen monster, never seen but always felt in horror to this day, has been the realm of the aural.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Great profile on a mastermind of composer.

Any song by Penderecki gives me intense spine chills. Though I am fairly traditional in my musical tastes, atonal and dissonant music is very fascinating to me. It’s definitely one of music’s most unique forms. And it definitely has some sort of a structure to it.

I used to make these radio plays for an amateur station. Whenever some genuine horror was required, I’d simply put a bit of Penderecki under it. Never failed to scare the living daylights out of everyone 🙂

I still love Penderecki’s 1960s modernist scores. They have a red raw convulsive beauty that’s utterly unique.

It’s pretty insane when you think about how music like his is made with traditional instruments.

For music class we once had to choose a composer from a list and present one of his works. Penderecki was on it.

How fitting that such an incredibly ominous and unnerving piece, and also one of the greatest in all classical music, was used in possibly the 2 greatest horror movies ever made – The Exorcist and The Shining.

this was also used on the simpsons episode were marge becomes a gambling addict and mr burns is scared of germs and saw them everywhere on smither’s face

This work is so deep it reaches the core of the listener. An early work, written in 1961 but it’s unsure whether Penderecki cared less about listener reaction or not. Whatever, it is as dramatic as it is innovative.

Perfectly describes any day at my parents house when I visit….married 50+ years, both in their ’80s and they still don’t get along.

Work by Penderecki perfectly conveys anguish and horror.

Composers like (early) Penderecki have had a profound effect on modern film composers. You can hear his influence in many many scores and not always horror scores. Probably the best example of recent times would be the score to Reign of Fire by the excellent English composer Edward Shearmur. A thrilling but terrifying assault on our audio senses – the extended techniques of Penderecki and the like are all over it but Shearmur somehow fashioned it all into a fascinating and varied listening experience that never gets boring. Highly recommended.

Best instance of Penderecking in films has to be that scene in ‘Shutter Island’ with the thundering Third Symphony: it’s just too awesome to exist.

I find it interesting how the music referenced here and the majority of iconic horror music and sound, in a way, serves a purpose outside of the realm of music. There is a level of simplicity that implies that horror music does not increase in effectiveness or quality parallel to an increase in complexity and musical satisfaction which is the case for most music. Instead, the music adopts meaning and substance by attaching itself to a fear or an emotion and then, when experienced, in short bursts, it triggers the attached feeling within the listener. This is similar to the effect of parallel editing in Eisenstein’s soviet montage. It does more than set a tone; it invades the senses as powerfully as an on-screen jump-scare or a devilish plot twist.

Nicely done. Very nice! If you don’t mind, I’ll be sending a link to this article to several friends. So pleased to have helped in the editing process. It’s often said that people only hear what they see, but in this instance I’d reverse that and state ‘people only see what they hear’. Without the work of Pendercki and his ilk, our cinema going experiences would be so much the poorer. Good luck with your further writing.

Thank you so much for your contribution, and for helping me with my first post for the Artifice. Please share, if you would like.

These days, I know more people who found their way into classical music through Xenakis, Penderecki, and Ligeti than I do people who came in through the ‘normal’ route of Bach, Beethoven, and Mozart. I’ve held conversations with 17 year olds about “Threnody”. I’m not sure exactly what all of this means, but I’m sure it speaks volumes about something.

I had exactly the same feeling, but did not pay too much attention to it as I should have.

Why was it possible to make radical music like that in communist Poland, but impossible in every other communist country? And the Polish exception wasn’t just in classical music. Polish jazz from this period embraced the most radical free-jazz currents too.

1960s Poland is so intriguing. For some reason, you could make really radical music there.

Lovecraft would approve of him, I guess.

Listening to his music while reading cthulhu mythos…

Krzysztof Penderecki is a master in aleatoric composition.

I finally found the style of a composer I was looking for all my life…

The way Penderecki applies the sheer depth and magnitude of sound one can achieve with an orchestra to capture existential, pants-shitting dread is absolutely flawless. hearing this from the first row of a concert at volumes that seem like they’ll flay the skin off your head must be incredible.

Classical music is not just about listening to works from long dead composers.

His music sounds like it came out of the darkest regions of the human mind.

Master of his craft. I plan to research more into the intersection of his music theory and biography that made him leave this kind of style into ones that had more of a lineage with the past.

I’ve been a huge fan of Penderecki’s Polymorphia.

All of his music is more terrifying to listen to than most modern horror films are to watch

Penderecki’s music sounds like fear…

The sounds of rage and agony.

Penderecki’s “Threnidy to the Victims of Hiroshima” was my gateway drug into avant classical music. Through it, I learned of such greats as Arvo Part, Ligeti, Stockhausen, Schnittke, Crumb. Gorecki, Xenakis, and many others. I simply love this music!

I believe that when the score of a film is good, you never remember it. But you do remember what the score evokes (the shower scene in PSYCHO, the shark in JAWS).

But Kubrick’s use of Penderecki’s music is interesting in THE SHINING, because Kubrick was not faithful to Penderecki’s original recordings; he adapted the music to suit the purpose of his own work. Unlike the John Williams or Bernard Hermanns of the world, Penderecki is not primarily a film composer. Yet his work is easily adapted to film soundtracks. It is very interesting.

The greatest composer!

I always thought of Penderecki as the composer that described best the deepest and darkest of human emotions.

The instrumentals in horror films definitely cushion the blow before a jump scare. You kind of anticipate something to happen and if it doesn’t then you’re left with the question of when will it happen? I’m not the biggest fan of horror films but I find it to be especially scary when the music doesn’t follow the theme of horror music. It makes it all the more creepier. The soundtrack from the Halloween movies however seem cheesy watching them as an adult.

It’s fascinating the way a composer can evoke horror, fear, and suspense through music. A composer can really help develop the mood of a narrative and impact the overall experience. Great Article!