Riddles in Rhetoric: Learning from Bilbo and Gollum about Linguistic Segregation

“It likes riddles, praps it does, does it?”

—Gollum to Bilbo in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit

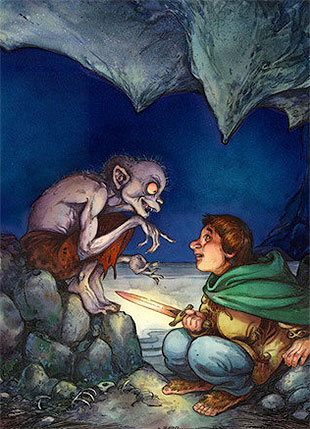

Thus Gollum invites Bilbo Baggins to the iconic game of riddles in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. 2 A fan favourite for many reasons, Tolkien relies on linguistic tells to define these characters’ relationships with each other. On the one hand, Tolkien unites Bilbo and Gollum through their shared cultural roots as hobbits; on the other, he establishes them as adversaries. This deliciously multidimensional exchange moves away from the grandiose physical battles that pepper Tolkien’s work, focusing instead on our most rudimentary skill—communication.

Language has already faced many revolutions. Writing, for example, changed our speech patterns, word usage, and memory. Today, the introduction of keyboards challenges the very act of writing while our digital communication platforms and the growing use of diction tools alter our vernacular. Living amidst this technological revolution, we are coming to rely on gadgets like Alexa, Google, and Siri. They become our personal assistants, sometimes taking the place of another person. So, how are these behaviours changing the way we communicate, and what do Tolkien’s linguistic constructions in “Riddles in the Dark” teach us about speech patterns today?

Tracing the scene from Gollum’s motivation for the game through the players’ establishment and conflict, we join Tolkien on a linguistic journey through the various levels of meaning—exploring the trust that communication inspires. Let’s begin with Gollum’s motivation for this riddle game. Bored and lonely, he recalls that he used to play riddle games before he succumbed to the Ring’s malice, and thus invites Bilbo to play with him. After Bilbo answers his first riddle with ease, Gollum challenges the hobbit to a game. What begins as an entreaty for company and entertainment evolves into a life-or-death competition.

As the scene unfolds, Tolkien uses layered linguistic meanings to create a rising tension between the two characters and to clue the reader into Gollum’s deceitful nature. According to linguists Michael Halliday and Ruqaiya Hasan, Tolkien is invoking the three functions of language, “the ideational, the interpersonal, and the textual.” 3 In other words, Tolkien draws on our understanding of meanings, implications, and language usage to steer our interpretation of the scene and its players. Together, these underlying elements guide our perceptions of individuals and govern our judgements of a situation.

Creating a Comforting Familiarity

Familiarity often comes as a source of comfort. We have sayings like “better the devil you know” that capitalize on the construct that the unknown is scarier. Especially within a fantastic setting, readers may turn to familiar icons to situate themselves—regardless of whether they are conventions within our world or tropes of the genre. These reader comforts can be expressed physically through appearance; however, as Tolkien highlights, linguistic tells can also serve as critical indicators of difference—hinting at which characters are trustworthy.

Throughout The Hobbit, Tolkien leads his readers to sympathize with Bilbo, encoding his token hobbit with behavioural and linguistic patterns intended to make him seem familiar. From his waistcoat to his pipe, Bilbo’s appearance often embodies an upper-class English gentleman. However, it’s Bilbo’s longing for home with its comforts and his bumbling attempts to fit in that draw a reader’s sympathy. Conversely, Tolkien encourages readers to mistrust Gollum not only based on his physical appearance but because of his inconsistent speech patterns and foreboding language.

Using Linguistic Figures as Identifiers

While the use of riddles is amusing, the game’s presence serves a much more complicated linguistic purpose—establishing the characters’ identities and their relationship with each other. Specifically, Tolkien uses the game to demonstrate Bilbo and Gollum’s similarities, while relying on the riddles and clues to emphasize their differing motives. By engaging in the game, Bilbo and Gollum recognize a shared background in riddles, and by making it a competition, Gollum is insinuating that he sees Bilbo as an equal. However, Tolkien highlights how tenuous riddle games can become if they venture too far into unfamiliar territory. As Bilbo and Gollum each realize this, they capitalize on their opponent’s weaknesses, exemplifying their differences. Nevertheless, the game’s parameters rely on Bilbo and Gollum’s commonalities to be a successful competition of wit. Tolkien goes as far as to demonstrate that, if answers are not given, instead of enhancing players’ enjoyment, the game becomes wearisome. To this end, Tolkien relies on these linguistically based logic puzzles to define who Bilbo and Gollum are as individuals—exposing their opposing opinions and experiences via the riddles’ clues.

Bilbo and Gollum’s use of language and choice of topics also mirrors their motives in the scene. For example, Bilbo’s riddles capitalize on natural phenomena—teeth, sunshine on flowers, and eggs—frequently invoking body-centric imagery like “white horses” for teeth and “golden treasure” for an egg. By contrast, while Gollum’s riddles about mountains, wind, the dark, fish, and time may evoke thoughts of natural things, he frames them with distinctly nefarious wording. For example, his clues use the foreboding phrases such as “ends life, kills laughter” and “cold as death.” Within the context of a life-or-death competition, Bilbo’s riddles and clues are filled with reminders of vitality, whereas Gollum’s fixation with death becomes explicit.

Tolkien uses these differences in wording to reinforce the danger, twisting a child’s game into a battle of their wills. Gollum’s status as an adversary is further emphasized through his deviant habit of speaking to himself. Another linguistically-based tell, Tolkien emphasizes this unfavourable trait by inconsistently misspelling words like “precious”—which has at least four different iterations, ranging from one to four’ s’-es (i.e. “precioussss”). The variation of spellings is representative of the character’s own untrustworthy nature, his erratic speech mirroring his inconsistent intentions.

Meanings, Implications, and Usage

Returning to layered meanings, in their book Cohesion in English, linguists Michael Halliday and Ruqaiya Hasan explain that language has “three major functional-semantic components.” Formally, Halliday and Hasan name these “the ideational, the interpersonal, and the textual.” In short, these elements represent language’s meaning, social implications, and usage. Tolkien capitalizes on these functions by encoding the riddle game based on our understanding and application of language to create a dynamically threatening environment.

The ideational component, Halliday and Hasan explain, makes up the base meaning of language, focusing on “the expression of ‘content’” and our ability to understand it based on shared experiences and logic. Tolkien invokes the ideational as he tells his story, implying that Bilbo and Gollum are logically able to engage in a game of riddles and to place wagers because they are at a roughly equal skill level. Building on this first level, Tolkien relies on the interpersonal meaning (the social implications) to clue the reader in to which character we ought to support. Bilbo’s mannerisms and language in this scene paints him as more ‘civilized,’ drawing empathy, whereas Gollum’s unreliable speech deters readers. The last indicator, the textual component, focuses on the use of language. Tolkien relies on the previous interpersonal level, building on our social perception of Gollum as ‘Other’ and reinforcing this sense of mistrust with Gollum’s irregular grammatical patterns.

Gollum’s misuse of language and abuse of grammar vilifies him. His meaning is both foreboding and inconsistent, indicative of an inability to communicate clearly or to interact according to social expectations. Tolkien uses the levels of linguistic meaning and word choice to cultivate this unfavourable impression. While Gollum is not the first character to be Othered, it is vital to consider how Tolkien achieves this affect—not only through his narrative but, specifically, through speech patterns. His layered grammatical choices immediately create distance between the characters, making the riddle game more contentious. The competition, which initially implies that Bilbo and Gollum had commonalities, instead creates a distinct intellectual hierarchy.

Lessons from Rhetorical Riddles

Halliday and Hasan’s principles about language complexity govern our everyday communications. For example, a grammatical error or odd speech pattern may lead us to perceive someone as less educated or even less intelligent. Although this “verbal class distinction” is demonstrated in a comedic setting in the musical My Fair Lady, it nevertheless persists as a very real sociocultural issue. 4

Such inconsistencies within a language may indicate a difference in education; however, they are also geographically based. For example, American English uses ‘color’ whereas all other English-speaking countries prefer the variant ‘colour.’ In this case, the appropriateness of the spelling depends on location—and becomes almost arbitrary when one is familiar with both iterations. Today, our digital ways of working breach international boundaries with unprecedented ease. Simultaneously, we bring more attention to these divergences of dialect while we trivialize their differences through routine communication and the act of collaborating with international authors. This turn to digital communication is also forcing us to reconsider what is acceptable vernacular. For example, we are constantly challenging previous rhetorical distinctions as texts and IMs replace letters, memos, and even emails in personal and professional spheres.

Vershawn Ashanti Young developed an argument for the wider acceptance of linguistic diversity propelled by a re-haul of grammatical standards. 5 Young defines “code switching” as the use of multiple grammatical systems, including cultural vernacular and slang. The switch, he identifies, is when we change our speech patten to match our social situation. In this context you are “code switching” when you use a different tone and vocabulary to email your boss compared to what you text your friend. Young argues that these judgements are a persisting form of “linguistic segregation,” and questions why we perceive certain dialects as inferior.

By these standards, an argument could be made that Gollum’s speech should not be condemned as lesser but instead acknowledged as different. It is for this reason that Tolkien’s scene remains pertinent today. He relied on readers’ perceptions of language to clue them into Gollum and Bilbo’s differing statuses—a system of judgement that we continue to perpetuate. Although a regulatory system is imperative to clear communication, we nevertheless must consider how we use grammar and whether such linguistic segregation is still applicable. After all, as our use of language evolves, shouldn’t we also adapt our perceptions?

The scholarship and prevalence of linguistic differentiation and distinction demonstrate the impact of these seemingly slight differences. They shape our perception of a person’s character and guide our ability to interpret and judge a scene. As our language and communication methods evolve, it seems critical that we consider not only how we want to be perceived, but that we question what systems are responsible for such judgements.

These linguistic tells are also a vital component when it comes to the successful development of Artificial Intelligence (AI). As our verbal exchanges grow in number and complexity, we are inadvertently training our virtual assistants like Google, Siri, and Alexa. They are learning not only how to recognize our unique speech patterns and accents but also how to communicate with us. Other AI seeps into our writing, shaping our communication from simple autocorrections to editing tools, like Grammarly. Some programs not only suggest these ‘corrections,’ but also craft our messages with features like Gmail’s Smart Compose. Therefore, as AI grows in prevalence, we must consider the impact of the speech patterns that we are imbuing them with and ask what implications these linguistic tells may have.

Works Cited

- Featured image by jim bryson. ↩

- Tolkien, J. R. R, and Douglas A Anderson. The Hobbit. Houghton Mifflin, 2001. ↩

- Halliday, M.A.K., and Ruqaiya Hasan. Cohesion in English. Longman, 1976. ↩

- My Fair Lady Broadway Cast. “Overture/Why Can’t the English.” My Fair Lady, Columbia Masterworks Records, 1956. CD. ↩

- Young, Vershawn Ashanti. “‘Nah, We Straight’: An Argument Against Code Switching.” JAC: A Journal of Rhetoric, Culture, and Politics, vol. 29, no. 1, ser. 2, 2009, pp. 49–76. 2. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

So you believe communication is our most rudimentary skill? It certainly is our most original ability.

I personally didn’t like how several times in a row, Bilbo answered a riddle by sheer luck alone (fish, time, etc). I think that’s a trick that would have been better used once.

There is more to luck in Tolkien’s universe than just a random stroke of fortune. Gandalf seems to have somewhere between a strong hunch to a near-complete conviction that Bilbo is the “chosen” one. And he makes this clear on many occasions – when the dwarves openly doubt Bilbo, Gandalf vouches for him, often even snapping at the dwarves.

That luck seems to favor Bilbo is no coincidence. There are too many instances of Bilbo and his party facing uncommonly good luck.

Tolkien makes several veiled references to the good luck and, depending on the point of view of the person, this changes ever so subtly. For instance, The Hobbit and TLotR, as we know is written from the hobbit perspective. (The Silmarillion, otoh is written from an elvish perspective.) Due to this, hobbits understand little about the intricacies of luck or the ancient Elvish myths. So it is perceived as “luck” or “chance”. But notice that when Gandalf or Elrond or one of the wiser folk (other elves, Aragorn etc.) talk about luck they have an ever so slightly different perspective. It is not uncommon to hear Gandalf say things like “Luck, if that is what you choose to call it, was with Bilbo that day”.

There are no coincidences in Tolkien’s world but at the same time elves and men (man even more so) have free will to shape their own destinies. This may be seem inherently paradoxical but it is not. Predestination and free will can coexist as long as said Predestination is ordained by a higher being. Boethius’ “Consolation of Philosophy” has much to say on this, if you’re interested. This idea is the one you will find criminally paraphrased as “God works in mysterious ways.”

So the hand of luck is very much central to Tolkien’s writings and one that seems to work so subtly that it is very easy to mis-attribute or even altogether miss.

Just Imagine walking through the Mountains and encounter this 500 year old Creature in a cave full of darkness, wanting to eat you whilst talking in your language. Pure Terror.

This was very insightful! I looked at the scene through a different lens while reading the article.

I really enjoyed this movie scene and book chapter. You get to really sense the sadness of the situation that is Gollum.

My husband is a huge Tolkien fan and I’ve heard him watching the 70s cartoon version of The Hobbit many times while I was cooking in the kitchen. I didn’t really pay much attention to it because I hated the animation style and all the singing. Now that I’ve started reading the book I totally get where the singing comes from – there are songs throughout the entire book.

I went back and watched the riddle scene in the cartoon version and I hated it. I really disliked how one of the riddles was done sort of like a song in the background. I think the PJ version of The Hobbit did a great job with this scene. I think it mirrored the book perfectly.

I do think Bilbo’s “win” was a bit fortuitous. I don’t think it was cheating because it wasn’t something that was planned. It was really convenient so he took it. You’d be a fool to not jump on that opportunity. I guess that was the Took side of his personality kicking in? The Baggins side would have been more of a gentleman about it, I think.

I think the movie did an absolutely wonderful job with this scene. One of the few scenes in the movies that I loved unreservedly. Andy Serkis was, as usual, amazing.

And it’s subtle, but this scene was also basically one giant homage to the old Hobbit animated movie. The camera angles Jackson used were mostly lifted straight out of the cartoon.

Very interesting article. Discrimination happens all over the world, and what is really strange to me that some accents are considered ‘cute’ and some push people away.

I’ve witnessed and experienced linguistic discrimination a number of times; firstly my son, who was born in Italy and is bilingual, gets made fun of by adults here in Italy for apparently having a strong English accent when speaking Italian, which isn’t true at all since he has learned Italian from his Italian dad as well as everyone in our town. He has only learned English from me. His school friends don’t seem to notice at all which makes me realise that it is simple ignorance from the adults who think it’s ok to make fun of a 5-year-old for having an accent which basically doesn’t exist, LOL. It gets on my nerves how every conversation with people results in discussion about the way we speak. It’s disgusting.

Another experience happened to me in England, on more than one occasion, because I’ve always been quite well-spoken which has often led people to believe that I am somehow stinking rich and as a result demanding more rent money or treating me as if I couldn’t possibly understand hardship….all of which is false since I was quite poor! One landlady, after just a week renting her room, demanded higher rent from me or she was going to confiscate my things. She then went on a tirade on how disgusting and snobby the upper classes were….at which point I had to say “what the hell are you talking about? What’s all this got to do with me?!” She clearly had a chip on her shoulder.

We need to educate these poor fools.

I call it linguistic profiling. Great article!

What a great analysis you have here. And I found the riddle competition really great fun and I found it very packed with suspense.

This was a really great read! A really insightful interpretation of the scene. LOTR has never really held my interest, but this was so fascinating to read.

An excellent article. Your last paragraph is particularly apt, especially when considering how our written and verbal interactions are being weaponised against us. I, for one, would never permit any digital assistant into my home. Those things are, in my opinion, evil. The more we come to rely on A.I. to ‘help’ us, the less we think for ourselves and our language will become ‘safe speak,’ robbing us of the ability to truly express ourselves.

LOTR and Gollum are among my favourites in high-fantasy. This article has to be among the most interesting I have read about Tolkien’s work.

I feel Tolkien makes Gollum more consistent with LotR and strengthens both Gollum’s and Bilbo’s character arc.

I was one of those who read Riddles of the Dark in the schoolbook. I was in 3rd grade then, I believe, and remember enjoying it quite a bit. Within a couple weeks I picked up the entire book and was hooked.

The chapter is a great introduction to the book, and was perfect for that type of reading schoolbook. It functions as a standalone story that is very easy to pick up on – going from Bilbo waking up to his escape through the gate. There is enough there to tell you there is an interesting story before and after it, but it’s also very possible to just enjoy the chapter on its own.

“Three Hearts and Three Lions”, a fantasy novel by Poul Anderson has an episode with a rather humorous riddle contest. I’ve always assumed it was an homage to The Hobbit. Most interestingly, the episode combines aspects of both Riddles in the Dark and the adventure with the trolls.

I my house, “I lied about the wheels” is a punchline that’s part of family legend.

It might well have been. On the other hand, it might be a case of Anderson and Tolkien both drinking from the same well of Northern myths and sagas where such riddle games are described.

I remember the late Avram Davidson complaining about people who commented that the stag hunting scene in his novel “The Phoenix and the Mirror” was obviously an imitation of the stag hunting scene in T. H. White’s “The Once and Future King”. As Davidson pointed out, the similarities were that natural result of the fact that both he and White based their scenes on the same medieval texts on stag hunting.

I wonder if Poul Anderson ever said anything on this point?

I do think it is very possible that Poul Anderson had read “The Hobbit” and was inspired by it to include the riddle scene in “Three Hearts and Three Lions”. However, without further evidence (such as a statement affirming or denying this somewhere in Anderson’s letters) we cannot say for sure.

I believe Anderson read Old Norse. I seem to recall reading a translation by him of Egil Skallagrimsson’s famous poem “Lament for My Sons”.

While we are engaged in this pleasant speculation, I wonder if Tolkien ever read Anderson? I think he would have enjoyed “Three Hearts and Three Lions”, also “The High Crusade”, “The Broken Sword” and “Hrolf Kraki’s Saga”. Of course, Anderson’s take on elves was rather different than Tolkien’s!

Good post! What we need is linguistic versatility.

B. you might enjoy Green Street; the movie. Westham United fans whose Cockney English is worn and used as a Team Uniform. A familiar face in it too acting an undercover American Journalist.

Tolkien, one of the true masters of fantasy. There will never be another like him.

When I read a collection of old medieval riddles I remember being surprised by how bawdy they were in comparison to the ones that Tolkien included, not a complaint as it’s obviously a book for Children but a lot of the older ones seemed to rely on sexual connotations leading the listener astray.

This is very interesting, I would think partly due to Tolkien’s strong relationship with the Catholic faith. He was also a professor who knew Old Norse mythology, and was well versed in the folklore of trolls under bridges demanding answers to riddles, so Tolkien would have known those bawdy versions quite well.

J.R.R. Tolkien is a legend. Thnak you very much for making my childhood so many times more awesome!

I had always struggled at school, shopping center, phone calls, hospitals and society itself at my accent or the way I emphasize my conversations yet I still struggle with that because I unconsciously speak in an accent that according to many people I know it sounds too natural or too standard accent. I never believe when people tell me that but I am starting to understand now what they and it’s funny that when I tell people, in person, I don’t know how to pronounce a word they would tell me oh don’t worry it’s fine if it sounds accented but it seems they say it because they do see my race and they just think I’m trying to replace my accent when I actually just don’t know how to actually pronounce that word.

I’ve been reading The Hobbit to my 6-almost-7-year-old, 1st grade daughter over the past several weeks. We’ll finish chapters 18 & 19 tomorrow. (I had wanted to take her to a Sunday matinee of the movie until I learned it had been rated PG13 and would run almost 3 hours. We’ll settle for the 1977 animated version on laser disc when we visit my parents.)

Riddles in the Dark was a really delightful chapter. It was her first encounter with riddles and I could see the gears turning and the lights illuminating as she began to grasp more of the possibilities of our English language: puns, word play, shades of meaning…

This chapter is one of my reasons for wanting to see the movie.

Riddle contests were an occasional feature of Ango-Saxon and Norse Sagas, and some of the riddles JRRT used dated back to Early Medieval times. In the Preface to FOTR he says something about such games being “sacred” or something of that sort to show Gollum’s depth of corruption in meaning to cheat.

The film presents it as Bilbo trying to save his skin by humouring Gollum’s bizarre whims. Thought it helped make more sense of the Riddle Game in a context that’s generally less whimsical than the original text, and minimises the moral awkwardness of Bilbo cheating. It’s also the most effectively tense part of the film.

Wow, this was a really fascinating insight into Bilbo’s encounter with Gollum. Thanks for writing this!

I loved this book. It was such a great classic. The Hobbit movies were just awful. They tried to make these movies as action packed as Lord of the Rings series and they really strayed from the storyline in some parts. The Hobbit is a much more simple story than the Lord of the Rings series.

The movie also made Smaug look like a wuss.

I like how Bilbo feels empathy to how pathetic and miserable Gollums life must be down there in the dark and slime, forever afraid and alone.

I remember when I first started reading the Hobbit, I knew the LOTR books existed, but had no idea if I was going to read them. After the riddle chapter in the Hobbit, I knew that I was going to finish LOTR without a doubt.

As Stephen King said in his Dark Tower series “a boy who could answer a riddle was a boy who could think around corners.”

YES! If you want to see a fun play on the riddle game, albeit a more adult take, book 4 (Wizard and Glass) of Stephen King’s Dark Tower series is great!

Glad to see this article made it into the lineup! Considering how carefully and thoroughly Tolkien worked linguistics into all his stories, this was a discussion that was long overdue.

A good essay on use of language to convey a perspective on Tolkien’s writing.

Really strong thesis you have here. Oh and I must confess that even though I’ve read the book twice before, I’m awful at figuring out the riddles on my own.

It seems that many people find a way to discriminate against others based on any and all differences they can discern. It’s sad and sometimes dangerous but must be “natural” because it’s so common. We need to grow up as individuals and as a society and move beyond this behavior.

In high school Enlish class, we were given the assignment of keeping a journal throughout the semester. So I used the front of the journal for my assignment articles, and in the back I wrote down the Hobbit riddles, just because I thought they were so cool and wanted to be able to read them whenever. I thought they’d be safe in the back of the journal since all my assignments were written in the front, but my teacher found them anyway and wrote the comment: “These are excellent! Did you write them?”

I still wonder if Bilbo was a serious riddle player… 🙂

Hands down my favorite author…I can read through the series and by the time i’m done, i can start over and read it again.

Hey, this is really cool! It’s always fascinating when popular fantasy stories successfully draw attention to real-world issues in an entertaining way. I feel like most people could learn about linguistic segregation (for example) much more freely and easily from a story like The Hobbit than they could simply by reading academic or other nonfiction articles on the topic.

An interesting question that follows from this is, does Gollum’s speech change at all when he’s trying to help Frodo and Sam in the Lord of the Rings series? Or does it remain more or less the same?

There is something so very frightening and so very chilling about this chapter, even the name brings a shiver of fear to my person; Riddles In The Dark. Tolkien is indeed a master craftsman.

What an interesting and engaging topic!

Yes but I’ve an objection, why bilbo had to exist when he can live peacefuly at the other side?

I really liked this article! Yes, I think you’re right about how linguistics plays a role in how readers perceive Gollum. It’s especially true when one considers the dynamic between Smeagol (a glimmer of Gollum’s past, “Hobbit” self) and Gollum (the irredeemable, “fallen” Hobbit). Tolkien plays with the idea of a “civilized” construct versus a “savage” nature in that way.

I have only recently watched the LOTR trilogy for the first time (The Hobbit will be very soon). A very interesting article, and I am excited to learn more about Tolkien’s work in both written and visual forms!

Great article

Great article, really interesting ideas.

The stratification of vernacular across a world like Middle Earth is particularly pronounced because most of the forms of language the reader is made privy to are represented in English. Yet English is far from a lingua franca for Middle Earth, in fact it sits quite low on the language hierarchy. It would be interesting to compare the representations of English and non-English vernaculars and to see how they are similarly stratified.

I appreciate your linguistic interpretation of the “Riddles in the Dark” chapter. I am curious to what complexity Tolkien actually wrote the scene? As in, were the choices of riddle topics and the use of riddles in general used to set a precedent of equal competition? Was he aware of the three linguistic components of language when he wrote it? From what I have learned thus far about Tolkien, I would not be surprised. As a linguist, he would have been aware of many facets of communication and as a writer, his characters were skillfully developed. It would make sense that the details of the scene were carefully orchestrated from a linguist’s perspective, to elude to a certain relationship between the characters and to showcase the distinctions between them.

As a linguistics major, I enjoyed reading this article and particularly the idea of bringing it to a great film series like the Hobbit.

“Riddles in the Dark” was always a favourite chapter of mine, and probably informed a lot of my present love for wordplay. Thanks for your fascinating insight into this scene and its linguistic depth!

Very interesting. I am really intrigued by the thought that we are training our AI. It would be funny to bring the home Google devices from different people’s homes and perhaps from different areas in the country/world together and see if they have indeed picked up different linguistic tells.

fascinating.