Analyzing Jane Eyre as a Contemporary “Bad Feminist”

Jane Eyre is, pretty indisputably, Charlotte Bronte’s most popular novel. This hallmark of Victorian literature, published under the pseudonym Currer Bell in 1847, took London by storm. Every influential magazine of the time expressed its opinions about the title character without reservation. And the reviews were widely mixed. Jane Eyre, the orphan governess who moves to Thornfield Hall and falls in love with its master Edward Rochester, was either an abomination to the name of “woman” or a spirited and refreshing female character. But either way, Jane Eyre was a raving success.

In the twenty-first century, many readers (especially female readers) relate personally to Jane’s mental and verbal cries to be treated as an equal. We rejoice when she stands up to the man who is in fact her future husband and declares, “I am no bird and no net ensnares me; I am a free human being with an independent will.” We support her as a pinnacle of feminism when she insists to Rochester: “Do you think because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! I have as much soul as you, and full as much heart!”

And yet…the novel’s ending. One question that has plagued the minds of readers, literary critics, and Bronte scholars alike is how to reconcile these feminist pronouncements with the novel’s more traditional ending. After such an independent life, is it a contradiction for Jane to return to Rochester and become a wife and mother? Is that it? Is the liberated Jane Eyre so easily domesticated? Well, yes and no…

Victorian Women and The Three Waves of Feminism

First, let’s take a look at the time in which Jane Eyre was written. The mid-1800s were the height of the Victorian era in England. What we today classify as “women’s rights” was not very well established, and “feminism” as a term did not exist. The so-called first wave of feminism did not truly begin until the beginning of the 1900s, and the focus was on suffrage rights and breaking the domesticity codes by picketing and rallying in public. The second wave started in the 1960s and became much more radical and self-conscious. During this time, women rebelled against overly feminine items of clothing, such as high heels and make-up, viewing these as objects of patriarchal oppression. The third wave of feminism is, perhaps, what Bronte would have most supported had she been alive today. During this wave, women have found the happy medium between independence and success in their careers on the one hand, and wearing bras and having babies on the other.

Yet before these movements of women’s rights began, the traditional Victorian woman’s life was spent within the home as the “angel of the house,” while her husband worked in the real world of corruption and immorality. The only two professions open to a single woman were becoming a teacher or a governess, as both Bronte did in her life and Jane herself does in the novel. This trope translated to literature with the female protagonist falling in love and marrying at the end of the story. And certainly this expectation for Jane to follow suit could not have been far from Bronte’s mind. Could this explain why she ended Jane Eyre in the way she did?

But perhaps Jane’s choice is not so uncharacteristic. So how do we reconcile the independent, spirited Jane Eyre, with the domestic “Mrs. Rochester” at the novel’s end? Or maybe a better question is, do we have to? Can the two sides of this female character exist simultaneously?

The “Bad Feminist” and Jane’s Power of Choice

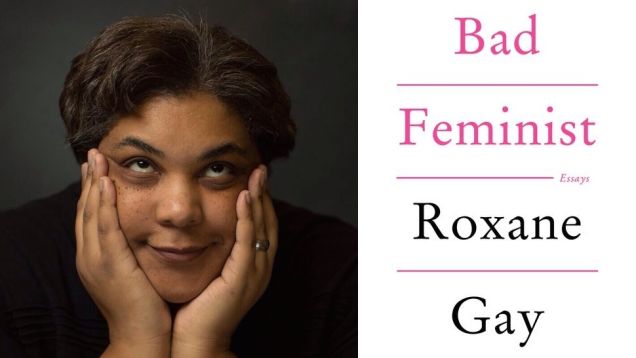

American writer, blogger, and editor Roxane Gay offers a new perspective on feminism in her works, specifically her 2014 collection of essays Bad Feminist, which we can apply to Jane’s multi-faceted personality and life decisions. Gay’s ideas lie mostly within the third wave of feminism as she argues for an outlook in which women are not required to be perfect, but instead allow themselves the freedom to be themselves and embrace their imperfections and contradictions. Gay openly proclaims that she self-identifies as a “bad feminist” in what seems to be a critique of the second wave. In explanation, she says that “I do so because I am flawed and human…I have certain interests and personality traits and opinions that may not fall in line with mainstream feminism, but I am still a feminist. I cannot tell you how freeing it has been to accept this about myself.”

Gay highlighted this call for acceptance of all kinds of women in her TED Woman Talk on May 28th, 2015 in Monterey, California:

“We put feminists on a pedestal and expect them to pose perfectly. When they disappoint us, we gleefully knock them from the very pedestal we put them on…If a woman wants to take her husband’s name, that is her choice and it is not my place to judge. If a woman chooses to stay home to watch her children, I support that too.”

Choice, as well as acceptance, are both integral to Gay’s perception of feminism. And when Jane makes the choice to become a domestic wife and mother, she does so through her freedom of choice, and is still the strong, uncaged bird that we have come to know and love. Although Bronte’s work preceded feminism by several decades, she may have agreed with Gay that, instead of a woman falling into one category or the other, she should be able to express her many contrasting tastes and impulses without guilt.

Jane shows that she is willing to give up a more intellectual and virtuous marriage choice in exchange for passion, love, and affection. Before returning to Rochester, Jane has been lodging with St. John Rivers, a country village clergyman, and his two sisters, Diana and Mary. Over the course of her stay, St. John proposes to Jane with the intention to marry and then move them both to India to carry out his missionary duties. Yet his austerity, coldness, and solemnity repel Jane. Later on, in response to Rochester believing that she has chosen to marry St. John, Jane insists on her freedom to choose her own husband in a way that was quite radical for the Victorian era: “‘He is not my husband, nor ever will be. He does not love me; I do not love him… He is good and great, but severe; and, for me, cold as an iceberg. He is not like you, sir; I am not happy at his side, nor near him, nor with him. He has no indulgence for me, no fondness.”

Here, what Jane reveals is that she could have chosen a more traditional Victorian lifestyle with a passionless marriage dictated more by duty than by love, but she did not. The paradox is that while she does choose the orthodox lifestyle for a woman, Jane’s refusal to become Mrs. Rivers and submit herself to St. John’s authority is a feminist act–and she can be a feminist solely on her own terms.

Compromise vs. Sacrifice in Marriage

Yet Jane’s motivation to embrace her domestic role as Mrs. Rochester also has to do with her awareness about compromise vs. sacrifice in marriage. While she recognizes that her union with Rochester will involve certain compromises, marrying St. John would have involved making personal sacrifices that Jane’s soul could not have survived. Gay addresses this distinction between compromise and sacrifice in married life by explaining, “I love babies, and I want to have one. I am willing to make certain compromises (not sacrifices) in order to do so.” While Rochester persists that he is an “old, lightning-struck chestnut-tree” who is blind and lame and will burden Jane with his needs, Jane defends the equality and freedom with which she makes her decision:

“Mr. Rochester, if ever I did a good deed in my life…I am rewarded now. To be your wife is, for me, to be as happy as I can be on earth.”

“Because you delight in sacrifice.”

“Sacrifice! What do I sacrifice? Famine for food, expectation for content. To be privileged to put my arms round what I value–to press my lips to what I love–to repose on what I trust; is that to make a sacrifice?”

Compromising, for both Jane and Gay, is worth it to have a secure home life. And this fact is something that Gay has finally realized she is tired of hiding: “I worry about dying alone, unmarried and childless, because I spent so much time pursuing my career and accumulating degrees. This kind of thinking keeps me up at night, but I pretend it doesn’t because I am supposed to be evolved. My success, such as it is, is supposed to be enough if I’m a good feminist. It is not enough. It is not even close.”

While Jane lived the first twenty years of her life relying on herself and exercising her self-sufficiency as an unmarried woman, her deep sense of loneliness, isolation, and stagnation cannot be overlooked in the novel. Her marriage to Rochester symbolises not only her power of choice, but also is the culmination of her feeling of communion with another human being–the one thing she has craved since birth. Bronte makes it clear that Jane and Rochester’s union is based on equality and a spiritual connection: “I am my husband’s life as fully as he is mine. No woman was ever nearer to her mate than I am; ever more absolutely bone of his bone, and flesh of his flesh.”

Sometimes, like in Jane Eyre, a strong and independent woman falls in love and wishes to adopt the roles of wife and mother by choice. While Bad Feminism and Jane Eyre differ in terms of genre and time period, both books remind us that terms like “feminism” deserve to apply to women of all shapes and sizes, who live lives and dream dreams of many different colors. Gay reveals toward the end of her collection of essays that she, too, was once preoccupied with a certain image of what a “true” feminist was: “At some point, I got it into my head that a feminist was a certain kind of woman. I bought into grossly inaccurate myths about who feminists are–militant, perfect in their politics and person, man-hating, humorless. I bought into these myths even though, intellectually, I know better.” Although written in the Victorian era, Jane Eyre and its ending can teach us the beauty of being both true to ourselves–whether we want to be an entrepreneur or a housewife/husband or both!–and being a feminist. As Gay puts it, “I am being open about who I am and who I was and where I have faltered and who I would like to become.”

Works Consulted

Bronner, Sasha. “Roxane Gay: ‘We Demand Perfection Of Feminists. We Do Not Need To Do That.'” The Huffington Post 29 May 2015. TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc. Web. 22 June 2015.

Bronte, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. New York: Barnes & Noble Classics, 2003. Print.

Gay, Roxane. Bad Feminist: Essays. New York: Harper Perennial, 2014. Print.

Gay, Roxane. “Roxane Gay: The Bad Feminist Manifesto.” The Guardian 2 Aug. 2014. Guardian News and Media Limited. Web. 22 June 2015. .

Walters, Helen. ““I Am a Bad Feminist and a Good Woman.” Roxane Gay Lights up TEDWomen 2015.” TedBlog. Ted Conferences, LLC, 28 May 2015. Web. 22 June 2015.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Thank you for this article! I never considered Jane to be a “bad feminist” to me having choices is feminist as you can get. I’ll check out some Roxanne Gay she seems awesome. Well done!

Thank you for your comment, Cagney! I’m glad you enjoyed reading my article.

I enjoyed reading your article; do you think we will see a time when we eliminate isms? Sexism, racism, classim, and feminism?

Thank you for your comment, Venus Echos! I certainly appreciate your perspective on “isms.” While they aim to simplify the conversations about such nuanced ideologies as “sexism” and “feminism,” they can also be debilitating. They also tend to encourage contrast and conflict rather than striving for a sense of cooperation. I would enjoy the time when these can be eliminated but I feel that, for now, they will continue to be used. I can only hope that when I use such terms, I do so to the best of my ability.

Great article! Feminism is certainly about choice, living the life you want and making the choices you want without trying to fit into anyone’s standard of gender, sex, race, class etc. Jane definitely embodies that in her choice to marry Rochester. Roxanne Gay sums up in the best way that we’re not going to every neatly fit into categories and that we shouldn’t try to.

Jane is feminist enough to choose the man she wants and desires.

Or woman.

I thought feminism was about being “essentially human” rather than “female”, i.e. defined by others which Jane refuses to be. And if we leave out the issues of CLASS which the book is also about, we have yet another ideological spin….

Thank you for your comment, chance! Taking a look at the intersection between class and gender in a Victorian novel like “Jane Eyre” would make a wonderful post in the Literature category. There is always more that can be said about any given topic, especially with such a nuanced topic such as the definition of “feminism.” Can such an ideology really ever be fully defined?

No film of Jane Eyre has ever matched the book. Maybe a 6 part mini-series could do it better but films are too short and too much has to be left out.

The reason why the mini-series of Pride and Prejudice was so successful was that there was time to develop the characters and plot lines.

And yes, Jane and Rochester are equals.

Thank you for your comment, Holli Bunker! Your thoughts about the power of the mini-series in conveying Victorian fiction so well would make an excellent post either under the Literature or Film category.

There are a lot of different types of feminism, but at the root of all of them is the following: gender equality (which Jane and Rochester end up with); and that women’s experience, however conveyed, is valid.

Just because a character hasn’t spent half the novel preparing for a Votes for Women march doesn’t mean s/he does not in his/her own way embody or pursue certain elements of feminist belief.

Thank you for this comment, Mitsuko Sipes! I certainly agree with your conclusion.

It’s been a while since I read Jane Eyre, but I loved it.

Jane Eyre is definitely a book for reading and re reading.

She is a self determined character who fights for her right to be treated as fully human, not as a drudge, or a stereotype or a nobody. She may well ‘fall for the bad boy’ but she refuses to allow him to compromise her beliefs and morals – she leaves until he is ‘ready’ to give her the respect she wants.

Still not a very good book, though.

Why do you say that, pete?

I couldn’t disagree more.

I respect your opinion, and I would love to hear your reasoning.

A feminist reading of Jane Eyre is not a current piety; it’s simply seeing what is there in the novel; and how many novels of the 19th century conclude with a couple as happy and equal with each other as Mr Rochester and Jane Eyre?

Certainly, TwoStep, many novels of the nineteenth century conclude in a similar fashion. Yet I would gesture to say that usually the power of choice behind the female character’s act of marriage is glazed over in favor of viewing her as the purely independent single woman.

My intent of this post was to show that a female character (or woman in reality) can call herself both an independent spirit and a domestic wife and mother. The choice of “Jane Eyre” as my example was based on my background with the novel; I would certainly encourage more articles on this topic that address other Edwardian and Victorian novels.

What really captures my heart in Jane Eyre is the wonderful empathy you feel with the character of Jane and also eventually Mr Rochester who seems nicer once his eyes have been burned off.

The feminist messages in Jane Eyre the novel and through her character are: Be true to your own sense of integrity; manage your circumstances as best you can, but don’t give in to compromise that undermines your own authentic sense of self lest you are reduced to a shadow of yourself; speak up however and when you can, if possible, about circumstances and events that really matter to you; assert your independence of heart and mind; maintain your self-respect against the odds and the social/political/societal status quo and adhere to your own high standards, not ‘theirs’. And how could I forget this one? Never let the bast*rds grind you down (or at least not long enough for you to stay down).

Jane is a woman from a poor background fighting against class and gender prejudice to succeed as a professional woman from a working-class background.

It’s far from imposing a feminist agenda/subtext to the story of Jane Eyre.

Thank you for this article. It’s just as problematic to say there’s something wrong with a woman for wanting marriage and family as it is to say there’s something wrong with her for not wanting them. A disturbing trend I’ve seen in criticisms of Mulan and Black Widow. Men with the same desires don’t get forced into being defined as only one thing.

We can’t manipulate our connections made with other people. Love triumphs over logic and so even the most hard nosed feminist or strong willed individual can become a traditional wife or mother. This doesn’t change our values on the importance of equity and fairness but rather we accept a compromise in exchange for harmony, peace and to share our life with the person we are betrothed.

To diverge slightly: while I have found many of the love cliches (love conquers all, etc.) to be true I have also noticed a pressure, often self inflicted, that manifests and unhappiness due to lofty expectations put in place by the media of romantic love. I am reminded of Kahlil Gibrans words: “your reason and your passion are the rudder and the sails of your seafaring soul.” The logic in love and the love in logic. As mentioned above in brief summary of third wave feminism, there is an element of balance.

I don’t know whether Jane Eyre herself is feminist but to write a character who does all that tramping across the moors etc and who pretty much fights for everything and who opts not to marry the missionary man and chooses her own path in life is fairly radical at the time from Charlotte Bronte.

Having just recently re-read Jane Eyre, I enjoyed this article very much.

The book was written long before the modern feminist movement but stands on the shoulders of Mary Woolstonecroft’s Vindication of the Rights of Women written forty or so years previously. demanding new possibilities for women as equal partners in Tom Paine’s Rights of Man .1847, when the book was published, was also the time of monster rallies for universal suffrage – Chartism – and an ongoing mass struggle against slavery.

Kudos to you, Rachel, for tackling such a multifaceted novel and complex lens to analyze it through. I think that Bronte sister’s novels are meant to defy expectations. Jane Eyre is at the forefront.

Wayne C. Booth wrote an excellent article and, although he focuses on Wuthering Heights, he touches on many key ideas that you insinuate in your article. He argues that these novels and-by extension-their characters don’t let the reader box them in.

Jane Eyre’s conclusion does exactly this. The reader thinks that they have defined Jane as a subversive woman, but she is constantly pushing these boundaries, dismantling the preconceived notions that people may have. In doing so, however, Jane is also subverting our new expectations that she is not a “feminist” per se. As you astutely highlight, this defiance is subversive in itself.

Really great article and well-written! Thank you.

And I am interested in Roxanne Gay’s opinion on bad feminism – because if one believes that a woman has the right to chose her path in life with equal opportunity, that is not being a bad feminist. Someone who looks down on a stay at home mom is being ridiculous, not a good feminist. They are not looking at the social, political and economic situations of patriarchal America. She also believes that mainstream feminism means looking down on women who chose the domestic life. That could be true, but I also think mainstream feminism has a lot to do with white feminism and popular feminism – the kind of feminism that is talked about only because it’s popular and not grounded in intellectual social theory. It seems to me that what she is saying is exactly mainstream feminism, that perhaps she has defined her own kind of feminism….Reminds me of what bell hooks might call faux feminism.

Awesome analysis! This is very well written and analyzed!

Thanks for this! It was a bit shorter than I was expecting, but still amazing nonetheless. I love Jane Eyre and both Bronte sisters. Interestingly enough, sometimes we still can’t choose our husbands now… But that is more of a personal matter. Thanks for the article!

Great points on how the popular notion of feminism can be so fickle, especially when connected to a female character that is lifted on such a pedestal. Jane Eyre, when analyzed on her feminism, reminds me a great deal of what happened with the character of Jo from Little Women by Louisa May Alcott. Like Jane Eyre, Jo was personified as an independent tomboy only to become a married housewife to Professor Bhaer instead of the fan favorite Laurie by the end of Little Women; a move that likewise seemed to go against Jo’s feminism in the eyes of many fans of Little Women even back in the 19th century. Again though, like Jane Eyre, it was still ultimately Jo’s choice to marry the man she loved. Alcott even similarly defended the decision for Jo to marry Professor Bhaer by stating “I won’t marry Jo (to Laurie) to please anyone” which clearly illustrates that feminist value of choice as mentioned in this article.

I loved your article! I am a huge Jane Eyre fan, but I never considered the role Jane’s choice plays in the novel, and I was intrigued by your perspective on it. I can see the way Jane’s freedom of choice is a large part of why the book resonates with feminists, myself included. Another aspect of the book I always see as pro-feminist is the way that Jane has a free discourse with Rochester, and the fact that at the end of the novel his disability, in a way, levels them; he has a need for her, which seems to make the power dynamics in their marriage more even.

I really enjoyed reading your piece. Jane Eyre is one of my more beloved novels. I think you took a good approach to analyzing the ending (considering how much is written about the novel using a feminist approach). I have always found the economic issue of the ending to be interesting. It is not until Jane is fiscally stable on her own terms that she allows herself to more fully embrace “wifehood”. Thanks for the article.

Yes, cesporz, and in addition to being “fiscally stable” before she marries, Jane is also in the position of power. While she says that “no woman was ever nearer to her mate than I am; ever more absolutely bone of his bone, and flesh of his flesh,” nevertheless, it is she, and not Rochester ( blind and maimed like the lightning-struck tree) who is now in control.

Fantastic article Rachel. I remember talking to you a little while ago about the premise of this – and you’ve done such an amazing job, taken it into a really interesting direction. It’s so well written and you’ve married what appears to be two very different women together in a really delightful, wonderful and interesting way. I really enjoyed reading this and as someone who loves Roxane and Jane Eyre – the content was an absolute bonus. Thanks.

I loved the way you included the different incarnations of feminism within your piece to show how feminism is a multi-faceted and complicated lens through which we can analyse literature. Perhaps what makes Jane a ‘bad feminist’ for me is her seeming disinterest in Bertha, Rochester’s first wife. Maybe my argument is clouded by subsequent reading of Wide Sargasso Sea, but as a woman who cries out for equality, how can she not question Rochester’s treatment of a woman he once loved? It’s something I can’t quite reconcile myself with when I read Jane Eyre.

I’d first like to state that I appreciate Gay’s perspective for its embrace of women.

As has been asked above, however, I have to wonder, “What about Bertha?” I cannot help but feel in the novel’s conformism to the Redeemer and Rake motif (Jane is responsible for saving Rochester’s soul, i.e. women are again the moral epicentre of society, taxed with upholding all virtue) that the book is in fact not very progressive at all; and if we measure the novel’s strength by its weakest point, it fails completely in its service to women through Bertha Mason. Combined with the colonial politics, Bertha’s mental illness and subsequent sequestration in the attic is framed monstrously. She is presented as a demonic, “savage” succubus of sorts, an imperialist caricature, who everyone (except potentially her brother) is quite happy to be rid of. Bertha’s suicide is completely unexplained in any way not serving to the Redeemer/Rake framework; and on the whole, I’m not convinced that embracing femininity is doing anything more than damagingly glossing over the major hole in the novel’s feminism.

Nice work! As a feminist, I’ve always felt ambivalent about Jane Eyre; her spirited childhood seems so at odds with her retirement to conventionality at the end of the novel, and especially with her unwillingness to marry Rochester so long as Bertha Mason is alive.

I think your information about the ideology of “bad feminism” could use a little bit more elaboration. Gay argues that she is flawed, BUT is still a feminist — but is it possible that Jane is a feminist not in spite of those flaws, but BECAUSE of those flaws? Is feminism not about the right to be a wholly flawed individual without it reflecting poorly on womankind as a whole? Is it not about the right to exercise traits traditionally viewed as “feminine” proudly (i.e. romance, passion, maternal feelings), because feminine traits are not inferior? I think you have the opportunity to complicate your ideas about feminism a little bit.

Also worth pointing out is that for many decades, Jane was viewed not as a “bad feminist” but rather, TOO feministic. Even Virginia Woolf, feminist and early LBGTQIA activist, thought that Jane was dour and “too angry for her own good” (or so she wrote in “A Room of One’s Own”). You touch on these ideas a little bit, and I realize that the development of feminist ideals is not the point of your article, but it might be interesting to expand upon how feminist views on Jane Eyre have evolved over the years.

if we analyse Jane Eyre in Victorian era, it can be even a revolution in women role. I am totally disagree that feminism is about hate of men. Feminism should show the women ability and intelligence for having equal rights for living. Jane is a girl who is fighting against conventions that were taboo for other women breaking them. for Jane that conventions are marriage conventions. On the other hand, it is a bad feminist novel because character of Bertha. the way was treated with her. the idea of Rochester about her and their marriage all are sucks and insult to wife and wife hood.this is a complex subject and should analyse more than a simple cm.

Ah, yes! I am currently reading and analyzing Jane Eyre for a Literary Studies class. I really appreciate the perspective of holding room for ambiguity: you can be feminist but still do things that other people claim don’t adhere to the strict “rules” of feminism, for example. I think that leaving room for grey, in analysis and real life, is important.

On the topic of equality, when you say that “Bronte makes it clear that Jane and Rochester’s union is based on equality and a spiritual connection,” I wonder: was it always an equal relationship? Was it only made equal after Rochester lost some of his physical faculties and his property, and Jane gained some wealth of her own? What might be the significance of this – that perhaps they were not equal at the beginning of their relationship, but that Jane chooses him when she feels that they are at last on the same footing? (Maybe that could be interpreted as the ultimate feminist choice!) I don’t really have an answer, but these were some things my class was discussing today, mixed with my own feelings, that came to mind. Lots of thoughts! Thanks for a great perspective!

I took a course on the Brontë sisters this past semester and I kept on bouncing between “yes, Charlotte Brontë is a feminist” and “no, she certainly is not”. I think the hardest part for me in (finally) deciding that she was a feminist was that I had to shift my definition of feminism. Growing up, I learned from the media that feminism was “girl power” and that “women don’t need men”. My definition has since changed. And with that shift of definition, my understanding of Charlotte Brontë’s choice to have Jane Eyre marry Edward Rochester also shifted. Jane wanted the choice to choose what she wanted to do. The part I wasn’t able to get over was that what she wanted was to be the domesticated housewife. I had to accept that choice and freedom meant that a person was free to choose whatever she/he wanted.

When the debate is lost, slander becomes the tool of the loser.

-Socrates

Rochester is somewhat of a martinet, often criticizing Jane harshly, especially with demeaning names. His copious use of pet names seems to be an unintended (by him, not by Bronte) compliment to Jane and insult to himself. The names are a white flag surrendering that her feminine mystery leaves him a confused behavioral proscriptivist. In essence, Rochester the sexist acknowledges that the souls of women are entirely more complex than men. In scientific terms, Rochester insults Jane because he is baffled by the results of the human female’s ability to bypass the corpus collosum’s function of forcing thought to be a one-hemisphere operation. But is Rochester, no pun intended, small-minded and small-souled? How much do I forgive him for being from another time? I know I don’t care for him.

On the other hand, I like Jane, and criticizing Jane as a bad feminist is like criticizing her for not creating the 19th Amendment or Lincoln for not creating NASA. We’ve got to cut her slack for acquiescing to Rochester’s (not so?) subtle cruelty since divorce – if she wanted to fight Rochester to that point – resulted in nothing for a woman – no property and no child custody – only a bad reputation and almost no chance of remarriage.

I loved your article! I haven’t read Jane Eyre in a while, but your article brings back all the lovely feelings I had while reading it. I do have one question, though. How do you reconcile Jane’s feminism and her disregard for Bertha Mason throughout the novel? As feminism is supposed to be advocating for all women, how does Jane come to terms with her husband’s mistreatment of his first wife and literally distinguishing her the madwoman in the attic? I’m interested to hear your thoughts on this topic. I have somewhat recently read Wide Sargasso Sea, which details Rochester’s meeting with his first wife, and I have such a different opinion of him now. Anyway, thank you for posting this article! It was such a great and enlightening read.

I’ve always taken issue with people who think that the ending of Jane Eyre is not feminist, and your article has exactly articulated why I feel that opinion is not fair to Jane. I’ve not heard of “Bad Feminist” but I am interested in giving it a read now. Thank you for this great post!

Lovely article. If Jane Eyre is a bad feminist, maybe we need to consult and extol more of them. 🙂 If anything, I think Charlotte Bronte was way ahead of her time in crafting a female protagonist who is both a career and family woman.

Please someone helps me “there is critics which said that Jayne Eyre is a feminist work whereas the others said no it’s not a fiminist work. (fiminist critics in jayne Eyre)

I hope someone Will provides me with some answers. Thanks in advance.

I loved this interpretation! Three cheers for bad feminists!!

i loved this book so much i want to smooch rochester