The Art of Adaption

Firstly, let us begin with a clear definition of what adaption actually means. According to the Oxford English Dictionary it actually has a plurality of meanings and applications, but most allude to the process of change due to an alternative purpose, function or environment. 1 This general definition when applied in a media context becomes “an altered or amended version of a text,” 2 or more specifically “the presentation of one art form through another medium.” 3 Of importance in these definitions is the simple act of difference, meaning that for an adaption to occur it must be formulated differently to the original version.

Adaption is not a new process. Humans have been adapting texts from different forms for thousands of years: it is the process of creating paintings, and visual art based on histories and spoken legends; it is the translation of poetry into prose; of the stage to the screen; and of course it is the novel or similar literary source into television and film. 4 While the process may not be new, it is still an area of great contention, as when content undergoes adaption it becomes subject to a variety of factors that will affect the resulting production. These forces may range from issues related to the nature of the source text, or the actual reason for the adaption, even the particular medium and market will play a role in influencing the outcome. The most distinct example of this is in the adaption of a large text, such as a novel, full of nuance and internal character development, which must undergo a process of compression to fit single film format. 5

What do the theorists have to say?

Within media studies there has already been a long standing discussion under the title of Theory of Adaption, which concerns the impact and processes of the act of adapting texts of various sources to the screen. There are actually a number of factors that should be taken into consideration when considering the process of adaption. Firstly has always been the issue of comparison – how can two texts be compared when they belong to two fundamentally different genres. 6 Although, for instance, a novel and a film may share common narrative traits, they do not share conventional traits that are the basis for delivering their narratives. In an effort to alleviate this difficulty many theorists simply argued that the adaption could not be compared to the original. Foremost among these was George Bluestone who argued that “it is insufficiently recognised that the end products of novel and film represent different aesthetic genera, as different form each other as ballet is from architecture.” 7 An interesting view that extended upon this idea was that even subsequent adaptions should be understood to hold a direct relationship with the original, not with each other. That their aim is not to develop and improve upon the adaptions or the original, but to sustain its presence in the zeitgeist. An interesting concept, but as noted further into the discussion, not one that is always maintained by directors and writers.

Most theorists have agreed that there is a fundamental difference in the mediums. As such the question becomes – how could two such different texts be actually compared? Linda Seger attempts to explain that it is not only the difference in the medium, but in the experience also:

The experience of reading a novel is quite different from watching a film. And it’s exactly this difference that fights translation into film. When we read a novel, time is on our side. It is not just a chronological experience, where someone else determines our pacing, but a reflective experience. 8

The act of reading and the act of viewing are two different experiences. Seger argues that pacing is a huge component that must be considered. As she points out “a good scene in a film advances the action, reveals character, explores the theme, and builds an image. In a novel, one scene or an entire chapter may concentrate on only one of those areas.” 9 This argument then helps sustain the original view of adaption theory that comparison cannot be made between two texts of differing mediums. Sarah Cardwell further reinforces this sentiment by blatantly stating that “an adaption from literature to the screen necessarily brings into being a separate, autonomous artwork that should be interpreted and evaluated as such.” 10 This seems fairly straightforward – when a new version is created in a new medium it should be honoured as a unique and separate text.

Alas, how do we then handle Shakespeare adaptions when Shakespeare’s own work was an adaption of historical story and not always in a new medium? Can this be entirely considered original work if it is an adaption of a previous story in the same medium? Macbeth for instance is an adaption of a Scottish folk-tale so that appears fine – it has been adapted from folk-tale to drama. However, King Lear published in 1608 was based upon a full-text play King Leir that had been published and performed in 1605 11 – yet we do not refer to this as an adaption. But we do consider every variation since as being an adaption. However, this is theatre that is performed, it is not comparing ballet to architecture, but instead is comparing two similar types of dance. For if adaption is the “process of adapting one original, culturally defined ‘standard whole’ in another medium” 12 then King Lear is not an adaption as it is not translated into another medium. So where does this leave it within the framework of adaption theory?

A better model for adaption then is to consider the idea that recognises:

A later adaption may draw upon any earlier adaptions, as well as upon the primary source text. In a sense, this understanding of adaption draws upon the model of genetic adaption for its inspiration, in terms of its increased historicity and its recognition of the role that each and every adaption, as well as the source text, has played in the formation of the most recent adaption. 13

This better accounts for the adaptions of Shakespeare. However, it does not address the largest accusation leveled against adaptions, and that is the issue of accuracy. Accuracy in criticism appears to range from the issue of historical accuracy all the way through “being true” to the original text. Interestingly in media theory the concern of fidelity has been well and truly debunked. Scholars Jorgen Bruhn, Anne Gjelsvik and Eirik Frisvold Hannsen suggest that the issue of accuracy within film adaptions has largely been disregarded as a concern due to the fact it can be considered the least “interesting and productive instrument with which to confront adaptions.” 14 Instead what becomes important is the simple measure of similarity and differences created by the particular context of the adaption. That adaption should be considered only as a cultural product; that “adaption is viewing within a more comprehensive understanding of the cultural and textual networks into which any textual phenomena is understood” 15 Then if fidelity lacks importance and context is everything, Shakespeare was merely reflecting a contextual point of view unique to his own adaption’s creation of King Lear. How well can this sentiment be applied?

Adaption and fairy tales

One of the best examples of how adaptions can reflect the context in which they are created is the development of the fairy tale. Although this strictly will not always reflect the true concept of adaption, as not all have been created in a new medium; however, there is a trajectory from the original oral stories to the 21st century cinema. Fairy tale is a loose label that separates it from legends and folk lore, however there is a lot of overlap. The oldest known fairy tale is considered ‘The Doomed Prince’ circa 1300BC, appearing in Egypt. 16 Many Greek and Celtic legends have also appeared as fairy tales at a later date. Around this period many oral stories began to be collected, an earliest example of this was the Gesta Romanorum, which was a collection of Roman and Oriental sources. 17 How this is related to the discussion is that this text was used as a source of lessons composed in Latin to be given by preachers. 18 We know that fairy tales were used for a myriad of reasons, yet this was one of the first steps in changing the purpose, and to a degree elements of the stories, to suit the new context. The first printed version of this was in 1473 and became a source for many writers, including Shakespeare. 19

The next adaption occurred in a similar form, this does not fit adaption as it is analysed above, but it was at least a translation between languages. In French society Madame d’Aulnoy and Charles Perrault took up the fairy tale form in their literary salons, they used this form as a mode for contemporary satire, again reflecting a changing cultural context. 20 At this time the fairy tale was not aimed at children, however by creating a satirical form Perrault developed strongly moral stories that were direct and applicable to children. Thus began the adoption of fairy tales into children’s literature. This progression continued with the work of the Grimm Brothers. Although they did take a redactive approach and transcribed the tales with attribution to the sources. It was their works that instated the fairy tale firmly into the UK nursery. 21 In many cases the integration of fairy tales into the nursery reinforced the moral role of the fairy tale and reflected strongly the dominance of the Christian ethos, even though many of these stories were originally from non-Christian cultures. As such the fairy tale as part of children’s literature began to be used as a way to reinforce expected cultural and societal norms.

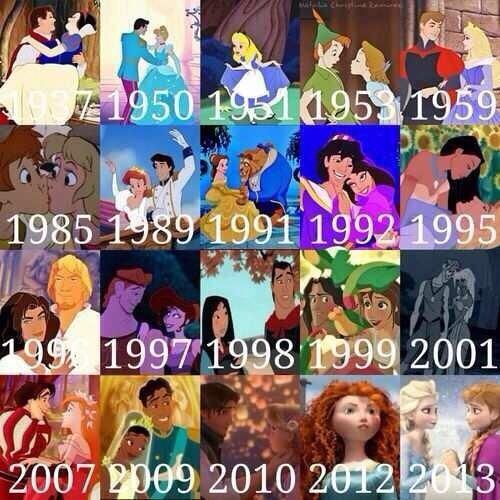

Since then fairy tales have risen and fallen in popularity. Early versions of fairy tales appeared quickly with the advent of the motion picture. One of the earliest films made, and the earliest fairy tale film was a rendition of Perrault’s ‘Cinderella’ in 1899 in France. 22 In America it was the Walt Disney Company that began to screen short silent versions of fairy tales in animation form. However, it was not until Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937 that full length feature adaptions of fairy tales began to emerge, with Walt Disney at the forefront. Where the earlier short renditions of the fairy tales were relatively brief but fairly true to the original source, the feature length versions were strong deviations from the original story.

There had already been conjecture and debate surrounding the suitability of the original fairy tale stories, especially those of the Grimm Brothers, for children. However, Walt Disney is an interesting examination of how adaption can truly be demonstrated – from written fairy tales to cinematic feature film. These films are also strongly altered to meet the needs of a number of different factors – cultural context and target audience being the foremost. The target audience is fairly obvious; there are a number of strongly violent and adult themes in the original versions of the Grimm Brothers’ tales (or the even earlier versions, which are often even more disturbing), and it is naïve to consider that a newly rising “family friendly” company would desire to show such graphic imagery on screen.

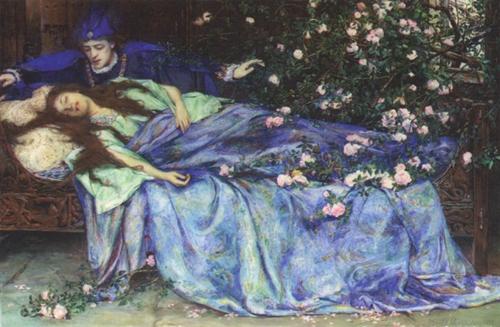

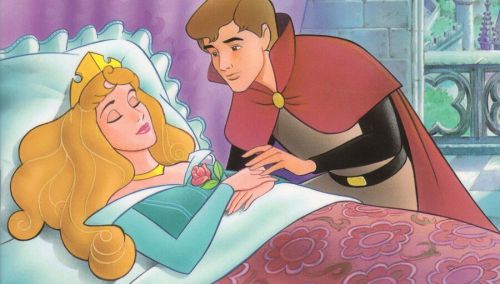

For instance, if accuracy to the original form is necessary then the original source for ‘Sleeping Beauty’ would never have made it onto screen, and for good reason. ‘Sleeping Beauty’ is an alteration of the story ‘Sun, Moon, and Talia,’ which is a much darker tale that incorporates rape, adultery and attempted cannibalism all of which are accepted by Talia. 23 Not a story that anyone would wish perpetrated into the modern world. Perrault’s version is, expectedly, less harsh but still disturbing with the prince still raping Sleeping Beauty, but he is unmarried and humour is injected into the story to appeal to his audience of the French nobility. 24 The Grimm Brothers’ version is ‘Brier Rose’ and rather than the rape and child birth focuses on the happy union of the prince who kisses her awake. A much simpler version of the story, but a more modernised and acceptable version.

Now, although the Disney version is purported to be based on the Perrault story, it is clear from this simple discussion that it was the Grimm Brothers’ tale that was used. Yet the claim would have been made as Perrault was perceived as more child-friendly while the Grimm Brothers’ tales had negative connotations of gore and violence. The big cultural change is in fact the removal of the Christian moralising of the tale, although “good conquers evil” this is not actual a moral standpoint. The film stresses family values and presents a female lead that fitted into the stereotype of the female Hollywood leads of the time (1950s) – blond, blue-eyed and slim. 25 She is a passive character who must wait to be rescued by the prince. There is an emphasis on the importance of true love, rather than the acceptance of prearranged marriage that is common in earlier stories, which is a reflection of the attitudes of American society. Adaption is a process and comparing each of the versions of what we know as the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ story tend to highlight this key concept that an adaption will reflect the cultural values and norms of the period in which it is created. But let us return to Shakespeare.

A Case Study: Romeo and Juliet

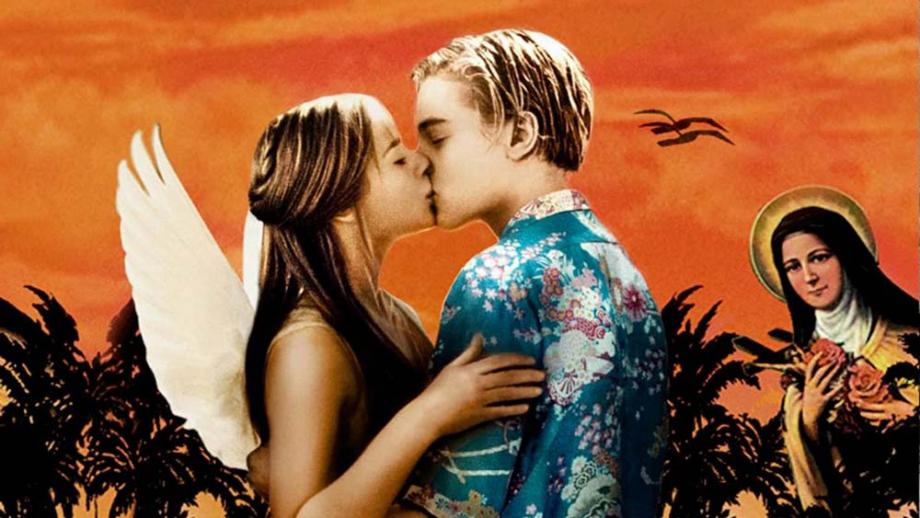

Adaption theory argues that each adaption should be analysed independently from others. The focus should be on what an analysis of the similarities and differences can reveal about the process of adaption that was engaged in. Here are three versions of a very famous tale, each a unique adaption from the original source material, which is William Shakespeare’s 1599 famous play, The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet: Jerome Robbins and Robert Wise’s 1961 West Side Story, Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 Romeo + Juliet, and the 2011 animated film Gnomeo & Juliet.

When applying this theory it would be represented as a relationship of A (Shakespeare) to B (West Side), then A to C (R+J), and then A to D (G&J). However, where this principle becomes difficult is in the assumption that each is an unique interpretation based only on the original work and not influenced by the milieu of the classic tale. The next step is that each variation is analysed according to the similarities and differences it shares with the original source material. With a story such as Romeo and Juliet’s tragic love tale there is so much present in the original narrative that is derivative of other work, of traditional legends and folk tales, it makes it difficult to identify if an adaption has been deliberately made or connected by association.

For example, West Side Story is considered a famous adaption into a musical, inspired by the original play. However, when the basic premise was formed during 1947 the only really common elements were in the feud between the families. The thematic focus is on racial and cultural differences and was exceptionally relevant to the time period in American when it was conceptualised. 26 There are more differences than similarities, but when viewed the resonance to the original play is so strong that the inspiration shines through. Other cinematic variants of Romeo and Juliet had already been present, but most focused on an attempt to present an Elizabethan version of Shakespeare. West Side Story fulfills the role of adaption theory as it is an adaption based on a single source, it reflects the period in which it was produced and showcases changing cultural values.

Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet released in 1996, thirty five years later, but equally “staged” in the sense that it is a cinematically alternative interpretation of the dramatic version. 27 It incorporates both original elements from the source material, but also elements that are more authentic such as a connection to the Italian context of Shakespeare’s setting. However, again the film is heavily adapted to meet the modern audience – it has guns, cars, overt drug use – but still maintains those elements from the original that resonate such as the purity of young love. Luhrmann decided the elements to change based on a careful analysis of the Elizabethan stage, however, he does claim that he “wanted to address Shakespeare in a filmic way rather than be shackled by all these rules and beliefs that are really spurious notions.” 28 Regardless of this choice to make a difference Luhrmann still maintained the original core theme, which concerned the issue of passing on generational hatred.

Gnomeo & Juliet was released in 2011 and represents the concept of the remix. It fits with the tradition of taking classic tales and transforming them into a children’s story, while also being a pastiche. 29 Remixing fits with the contemporary concept that there is no such thing as an original idea, as such the film incorporates cultural references, including direct conversation with Shakespeare about the end of Romeo and Juliet. Unlike the other two versions that conformed to the A to B and A to C formation of adaption theory, Gnomeo & Juliet deviates from this form, making it a more difficult analysis. The director Kelly Asbury states that in preparation “I watched the play, I watched Baz Luhrmann’s version a lot, I watched [Franco] Zeffirelli’s version. I saw all of the different interpretations of Romeo and Juliet and how they’ve been reinterpreted in different ways and the cleverness of some, and what I thought worked and what I thought didn’t.” 30 Each adaption is a strong reflection of the period it was produced in and, equally is a reflection of the process of the adaption. Where Luhrmann clearly draws on his background in theatre, and even opera, his focus on the original source is very clear. The work of Robbins and Wise equally reflects that although true to the original, the story of racial and cultural division in America was a more dominant focus for the directors. In turn Asbury was immersed in the source and the adaptions, which is clearly reflected in the remix pastiche form that the animation presented.

Author Lucas Worcester offered a final thought:

One of the main things to recognise about adaptions is that, adapting a media text is not necessarily down grading the quality of the original work. Each adaptation is unique in its own rights and provides various new ways to interpret a classic text or idea. Just because a text reflects a traditional idea, does not mean it is diminished in value. 31

Shakespeare is arguably the best known playwright, yet in his own way he was an adaptor also. He brought his own vision and flair to the works he adapted. It can be argued that each new adaption of Shakespeare’s canon is a matter of honouring these great works, to keep him not of an age but for all time. 32 It can easily be argued that his plays can be performed anywhere in any form and they will still be recognisable as Shakespeare. Do these adaptions diminish his works? I would say no. Are they accurate, do they uphold fidelity? No, but does that matter when, to paraphrase the great playwright – is not all the world a stage?

The issue of real life adaptions

Now all of that rhetoric is pleasing, however, there is an area of adaption that does need some distinct consideration and possibly some criticism. The greatest accusation of course against adaptions is the issue of accuracy in relation to film based on either real people’s lives or real events. It is here that the question of accuracy and fidelity holds more weight. Part of the issue is the introduction of the question of ethics and truth. As when addressing the question of original versus adaption, historical fiction is particularly interesting due to its need for a double reference to not only the existing artefacts or sources, and to the actual past itself. 33 Cardwell provides an interesting example when considering the creation of dramatic recreations. For instance when a documentary filmmaker creates a film on the life of Queen Elizabeth they would use a variety of sources that are directly referenced in the film. In contrast a dramatic recreation provides no indication of primary and secondary sources, it necessarily adds dialogue where no historical account existed, and would often be necessarily expressed in a modern, accessible tongue. As such this is no longer a “truthful” account of the life and times of Elizabeth. 34 Does this matter?

Some argue that it does not, that instead fiction is a free-for-all and as long as an author or filmmaker can find someone to produce their work there are no actual rules about taking liberaties with the truth. 35 In fact writer Meg Rosoff goes so far as to summarise her argument into fifteen words: “Do what you like, only do it well – and don’t expect the relatives to approve.” 36 A relevant sentiment, but this then underplays the importance of the source material. Other critics argue that history is real life – that it is meaningful, insightful and important. That necessarily they must pare down the complexities of the real world into “easy to approach” narrative arcs, which is not a reflection of real life. 37

Author Tasha Robinson provides the example of the popular Disney film Pocahontas, which was initially advertised as an educational film reflective of American history. It is of course hugely inaccurate and goes as far to attempt to white wash a true story of murder, rape and abuse. Met with great outrage a Disney representative attempted to dismiss the concerns with an attitude that as this was for children and it was an entertainment it should not have been taken so seriously. 38

Of course, it can be argued that in a postmodern world there is no such thing as a definitive truth. That the issue of fidelity is moot since film fundamentally is about manipulation and illusion, not truth and reality. 39 Even though film can be considered unstable as a form of historical preservation, it is a powerful medium that makes an impact. 40 It is this power that concerns many viewers. If a medium with such reach and impact deliberately misconstrues important truths this can be perceived as detrimental to society as a whole. There is no easy answer to this concern, but perhaps it is like most things and requires a modicum of common sense – that we do not simply accept something as truth without questioning it further.

The adapter as auteur

The final discussion to have concerns the accusation leveled at directors and writers of adaption films – that by choosing to use a source material already well developed they are not true artists. An auteur is perceived as a director that influences their films so strongly that they are considered the true “author” of that film. Often such directors are ones that have engaged in writing their own screenplays or have utilised the works of no-name authors allowing them great artistic control over the production. Interestingly there is often some doubt in the ability of adaptors to reach auteurship, yet three unquestioned auteurs who were adaptors are Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick and Walt Disney.

Hitchcock is often overlooked as an adaptor due to the signature traits of his work. To establish himself as an auteur he needed to take authorship from the writers, and his films were often retooled as a Hitchcock original that “promised not the literary values of their properties but the reliable generic thrills, set pieces and ironic yet reassuringly familiar markers of the Hitchcock universe.” 41 Walt Disney, of course, built an empire upon the adaption of fairy tales into film, making significant changes to the works to clearly create a unique “style” that is still recognisable as being “Disney.” This also aligns with the particular contemporary ideas of there being no truth or reality that belong to a single viewpoint. It then makes sense that those directors who are able to place their thumb print on their work are creating a unique work.

Ultimately it appears that modern adaption theory has a valid point, which is that when an adaption occurs between mediums a unique artwork is created. Returning to the original definition of adaption that it is “the presentation of one art form through another medium.” 42 It is easy to see how open ended such a definition leaves opportunities for filmmakers to create their own interpretations, to develop their own art, and to leave their mark upon tales that are already enmeshed in our zeitgeist of storytelling. Equally this leaves a viewer in an ambiguous place where they are being asked to ignore the history of literature and experiences they have already undertaken with a particular story line and remove this from their viewing of the “new” film. This is frankly an impossible undertaking, which leaves the new understanding of adaption theory, which is the importance of context – that by acknowledging the new work has been produced to reflect a particular set of forces and factors, this is what helps make it a new and unique undertaking. This is what helps make adaption an art.

Works Cited

- Brokenshire, M. (2018). ‘Adaption.’ The Chicago School of Media Theory. Retrieved from https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywords/adaptation/ ↩

- Brokenshire, M. (2018). ‘Adaption.’ The Chicago School of Media Theory. Retrieved from https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywords/adaptation/ ↩

- adaption. (2018). Film Terms Glossary. Retrieved from http://www.filmsite.org/filmterms1.html ↩

- Brokenshire, M. (2018). ‘Adaption.’ The Chicago School of Media Theory. Retrieved from https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywords/adaptation/ ↩

- Brokenshire, M. (2018). ‘Adaption.’ The Chicago School of Media Theory. Retrieved from https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywords/adaptation/ ↩

- Cardwell, S. (2002). Adaption Revisited: Television and the classic novel. Manchester, UK: Machester University Press. ↩

- Cardwell, S. (2002). Adaption Revisited: Television and the classic novel. Manchester, UK: Machester University Press. 12. ↩

- Seger, L. (1992). The Art of Adaption: Turning fact and fiction into film. New York: Owl Books. 13-14. ↩

- Seger, L. (1992). The Art of Adaption: Turning fact and fiction into film. New York: Owl Books. 16. ↩

- Cardwell, S. (2002). Adaption Revisited: Television and the classic novel. Manchester, UK: Machester University Press. 28. ↩

- Cardwell, S. (2002). Adaption Revisited: Television and the classic novel. Manchester, UK: Machester University Press. 18. ↩

- Cardwell, S. (2002). Adaption Revisited: Television and the classic novel. Manchester, UK: Machester University Press. 16. ↩

- Cardwell, S. (2002). Adaption Revisited: Television and the classic novel. Manchester, UK: Machester University Press. 25. ↩

- Bruhn, J., Gjelsvik, A., & Frisvold Hanssen, E. (2013). ‘“There and back again”: New challenges and new directions in adaption studies,’ in Jorgen Bruhn, Anne Gjelsvik and Eirik Frisvold Hannsen (Eds.). (2013). Adaption Studies: New challenges, new directions. London: Bloomsbury. 5. ↩

- Bruhn, J., Gjelsvik, A., & Frisvold Hanssen, E. (2013). ‘“There and back again”: New challenges and new directions in adaption studies,’ in Jorgen Bruhn, Anne Gjelsvik and Eirik Frisvold Hannsen (Eds.). (2013). Adaption Studies: New challenges, new directions. London: Bloomsbury. 8. ↩

- Fairytale. (2017). Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Retrieved from http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=fairytale ↩

- Fairytale. (2017). Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Retrieved from http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=fairytale ↩

- Fairytale. (2017). Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Retrieved from http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=fairytale ↩

- Fairytale. (2017). Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Retrieved from http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=fairytale ↩

- Fairytale. (2017). Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Retrieved from http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=fairytale ↩

- Fairytale. (2017). Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Retrieved from http://sf-encyclopedia.uk/fe.php?nm=fairytale ↩

- Cinderella (1899 film). (2017). Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cinderella_(1899_film) ↩

- Doster, I. V. (2002). The Disney Dilemma: Modernised fairy tales or modern disaster? University of Tenessee Honors Thesis Projects. Retrieved from http://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/532 ↩

- Doster, I. V. (2002). The Disney Dilemma: Modernised fairy tales or modern disaster? University of Tenessee Honors Thesis Projects. Retrieved from http://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/532 ↩

- Doster, I. V. (2002). The Disney Dilemma: Modernised fairy tales or modern disaster? University of Tenessee Honors Thesis Projects. Retrieved from http://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/532 ↩

- Worcester, L. (2015). Romeo and Juliet. Retrieved from http://www.mediafactory.org.au/2015-media1-projects-onestepfurther/2015/05/30/romeo-and-juliet/ ↩

- Worcester, L. (2015). Romeo and Juliet. Retrieved from http://www.mediafactory.org.au/2015-media1-projects-onestepfurther/2015/05/30/romeo-and-juliet/ ↩

- Adamek, P. (2013). Romeo and Juliet, Interview with Baz Luhrmann. Retrieved from http://members.ozemail.com.au/~catman/pop/film/ci/interviews/baz.html ↩

- Worcester, L. (2015). Romeo and Juliet. Retrieved from http://www.mediafactory.org.au/2015-media1-projects-onestepfurther/2015/05/30/romeo-and-juliet/ ↩

- Eisenberg, E. (2012). Exclusive Interview: Gnomeo and Juliet Director Kelly Asbury. Retrieved from https://www.cinemablend.com/new/Exclusive-Interview-Gnomeo-Juliet-Director-Kelly-Asbury-23117.html ↩

- Worcester, L. (2015). Romeo and Juliet. Retrieved from http://www.mediafactory.org.au/2015-media1-projects-onestepfurther/2015/05/30/romeo-and-juliet/ ↩

- Hammond, L. (2013). Do Film adaptations of Romeo and Juliet enhance Shakespeare in contemporary society or undermine his cultural status? Retrieved from http://arts.brighton.ac.uk/re/literature/brightonline/issue-number-four/do-film-adaptations-of-romeo-and-juliet-enhance-shakespeare-in-contemporary-society-or-undermine-his-cultural-status ↩

- Brinch, S. (2013). ‘Tracing the originals, pursuing the past: Invictus and the “based-on-a-true-story” film as adaption,’ in Jorgen Bruhn, Anne Gjelsvik and Eirik Frisvold Hannsen (Eds.). Adaption Studies: New challenges, new directions. London: Bloomsbury.224. ↩

- Cardwell, S. (2002). Adaption Revisited: Television and the classic novel. Manchester, UK: Machester University Press. 16. ↩

- Rosoff, M. (2010). Tackling real-life characters in fiction is fine – as long as you do it well. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2010/jun/22/sharon-dogar-annexed ↩

- Rosoff, M. (2010). Tackling real-life characters in fiction is fine – as long as you do it well. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2010/jun/22/sharon-dogar-annexed ↩

- Robinson, T. (2013). The problem with “based on a true story.” Retrieved from https://thedissolve.com/features/the-conversation/156-the-problem-with-based-on-a-true-story/ ↩

- Robinson, T. (2013). The problem with “based on a true story.” Retrieved from https://thedissolve.com/features/the-conversation/156-the-problem-with-based-on-a-true-story/ ↩

- Welsh, J. M. (2006). ‘Foreword,’ in Costanzo Cahir, L. (Ed.). Literature into Film: Theory and practical approaches. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. 1-2. ↩

- Welsh, J. M. (2006). ‘Foreword,’ in Costanzo Cahir, L. (Ed.). Literature into Film: Theory and practical approaches. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. 5. ↩

- Leitch, T. (2007). Film adaption and its discontents: from Gone with the Wind to The Passion of the Christ. Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ↩

- adaption. (2018). Film Terms Glossary. Retrieved from http://www.filmsite.org/filmterms1.html ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

This is a strong and engaging analysis. To me the ‘medium is the message’ in art…how you tell a story is as important as what the story is about. That message comes through in this work. Bravo!

It’s rare that I find a film better than the book that inspired it (and I always where possible try to read the book first so my mind isn’t corrupted by actors etc.).

There are a few exceptions in my mind though: Fight Club, The Ring (Japanese version), Planet of the Apes (claimed unfilmable?)

However I’d say the majority of films really don’t live up to the books, one example comes to mind: Moby Dick.

Middle ground cases include 1984 in my opinion.

Adaptation is art and sometimes, superior to the source. Example, I would add Godfather and Thin Man to the list of movies that improved on the written source material.

I would add many more movies! For example:

– Die Hard

– The Shining

– Apocalypse Now

– My Summer of Love

– Silence of the Lambs

– Stand By Me (ok, from a collection of short stories, as is…)

– The Shawshank Redemption

– Blade Runner

– Don’t Look Now

…and the Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit.

Lord of the Rings… The films were infinitely more interesting than the books.

Sorry, can’t agree with you there. The books have an emotional depth and richness that the films don’t match.

The Shining is a great film but it is a shocking adaptation of King’s book.

Greatest adaptations are currently being aired on the silver screen.

Stephen king’s 11-22-63 was severely trimmed to make it into an 8 part series and I am in two minds about how well it worked. I am sure that for someone who has not read the book the final result is a great story but the book is one of may all time favorite novels and I wanted an adaption that was as long and detailed as the novel’s 740 pages. It gets an 8 on a one to ten scale for adequate adaptions.

Another series that comes to mind as an example of a quite faithful adaption is “Outlander” which manages well match the books and not loose very much at all from its long narrative when it was translated to the screen. But I suspect that what it boils down to is the potential for a novel or a series of novels to sustain a continuing franchise and with King’s wonderful novel it was only ever going to be able to sustain a single season as its narrative is clearly got a definitive end point as you can only save Kennedy once but something like “Outlander” has the scope to span several years and a continuing franchise and that means it can offer greater returns than 22-11-63 so what it became was essentially a rather long movie told in eight episodes more than anything else.

Gomorrah was an interesting idea on an adaption of a book and ended up with a pretty enjoyable series, not sure they captured the depth and extent of organised crime the book goes into, but was pretty compelling viewing nether the less.

The TV adaptation of Psycho is an interesting one. The movie may be regarded as a classic, but it looks pretty ropey these days – tediously slow to start, never particularly believable, and no longer especially scary. Whereas Bates Motel spun the story into five compelling seasons, made the characters infinitely more fascinating, ramped up the tension considerably, reversed a good deal of the casual sexism and misogyny of the original, and damn nearly succeeded in making the whole saga plausible (and failing that turned the silly excesses into moments of enjoyable high camp).

I adored Bates Motel – once it dispensed with the weird Twin Peaks sex-and-drugs ring town sideplots and focused on the central story, it became must-see TV. Couldn’t recommend seasons 3-5 more.

Sometimes a TV adaptation complements the written work and you can enjoy both. I thought this was the case with Tom Stoppard’s version of “Parade’s End”. It really made me think about the skill required to pull this off. A novel in 4 volumes written largely inside the characters’ minds with a looping narrative structure ? How on earth do you get a 5 episode mini-series out of that ? Well it helps if you are a bit of a genius like Stoppard.

Can I shout out for The 100 ? Adapted from a book series I haven’t read but wasn’t particularly critically acclaimed, and it has a certain brilliance despite terrible science (especially after the first season, where the big question is ‘why is Finn a protagonist?’). I really like the way the characters wander back and forth across the moral event horizon – and this sounds like a criticism, but it is not.

Really interesting article and topic. How do you all feel critics should review adaptations?

Technically I’d say that a decent critic would ignore the book, and ignore any previous adaptations, TV spin-offs, etc. The film should be all that’s considered – I’ve never liked the apologists of bad films who insist that you should read the book to understand the film – that’s just a bad adaptation.

Practically though, it’s difficult if you’ve enjoyed the source material because you come with expectations.

Actually, the Harry Potter films are a great example to use and Im pretty sure that lots of readers are familiar with both the books and the films.

If the film adaptation is of a book as popular as Harry Potter, Lord or the Rings etc. then I think it is a cheating your readers if you review it without reading the source material as well.

Surely this is what the majority of readers/film goers will have done, and the main question for them is whether or not the film reflects the book that they loved?

With Harry Potter, personally I read all the books first, and have watched the films as they are released. The first three films I loved as they were very close to the books, however films 4 and 5 infuriated me as key elements of the plots (in my opinion) were missing.

I found the Half Blood Prince a little tedious as a book, so I found that I wasnt as critical with the film and actually really enjoyed it, despite it again leaving elements out.

However my children have watched all the films first and are only now reading through the books with me. Granted they have a child innocent view, however they love films 4, 5 and the Half Blood Prince as they are full of action and they don’t notice the flaws in the script. It is only now we are reading the books that they keep saying, why wasnt this in the film?

The reviewers job is to give people a snippet of the film to allow them to make their own decision about a trip to the cinema.

If you are familiar with the book, then the skill is to reflect on how successfully it has been adapted for the big screen, but also to pick out the singular merits of the film.

However, the review should comment on whether the film stands alone or not. This can then help those who havent read the book to decide on viewing the film or not.

A tricky task indeed but, in my opinion, you are better equipped to make a judgment if you have all the material at your fingertips.

Otherwise, you could find yourself a date who hasnt read any of the books, take them along to the screenings and then combine your views to make a 2 in 1 review.

A bit of work, fun, friendship and two opinions combined into one review. 🙂

The Potter films are an interesting one – on the one hand, I think they’re very entertaining and they don’t exclude non-readers. As somebody who loves the books, I certainly enjoy them too and think they work as a film series in their own right.

On the other hand, having read the books I think a lot of important plot points get missed; possibly by necessity, given the length of the later installments.

I did a screenwriting course and we were told that writing a book is easy in comparison and having attempted both I would say this is true. Credit to those who can adapt novels to screenplays and keep the essence of it all.

For me, the pertinent question in relation to the source material isn’t how absolutely to the letter faithful the adaptation is. My questions are:

a) whether it successfully identifies and uses the significant themes and emotional character arcs

b) whether it requires the viewer to have read the source material in order to appreciate the film.

The answers IMO ought to be yes to the former and no to the latter. If you don’t succeed in the first then you’ve failed as an adaptation, if you alienate those unfamiliar with the source material then you haven’t successfully created a standalone film.

I think it’s possible to make a poor adaptation that still works as a movie independent of the book though. If you have an “adaptation” that appears totally unrelated to its source material then it usually means the point of the book was either totally missed or wilfully ignored, but that doesn’t necessarily preclude the filmmakers from telling an interesting story; it just wouldn’t be the story it was advertised as being! In that event, if I was reviewing I’d warn people to put the book right out of their minds because they’d be seeing something different.

That’s why I think identifying the themes and emotional arcs correctly is so important – so long as you stay true to those the core of the source material remains recognisable and I think audiences will accept alterations. Change them too much and you remove what attracted people to the story in the first place.

Your comments seem to me right on target! “Faithfulness” shouldn’t be a standard at all. A good film adaptation has to be a lot more than simply a literal translation of the printed source to the big screen.

When I am unfortunate enough to listen to people telling me that ‘the original manuscript is far superior to this popcorn trash’ I normally assume that the person is trying to make me feel inferior. It has little to do with objective assessment and everything to do with the hierarchy of differing aesthetic media.

It’s a tricky one. I think the most important issue for a reviewer to consider is whether it stands as a film in its own right. That has to be the primary objective for any filmaker, so make a valid piece of art/entertainment, regardless of the source material.

I think the extent to which the source material is relevant to the review depends on the relation of the film to the material. If it’s just inspiration for, the jumping off point for the writer/director’s own ideas, I don’t think it matters too much. So thinks like Benjamin Button, Stand By Me etc aren’t really adaptations of books, since by necessity the story needs to be expanded.

But where the film is intended to be, and billed as, an adaptation of a book, then I think the source material is relevant since it must be one of the filmaker’s intentions to adapt it well. So The Time Traveller’s Wife is billed as the adaptation of the best selling novel, and so whether it was successful in adapting the ideas, themes and plots to another medium is relevant. So something like From Hell may work as a film, but is a terrible adaptation since it misses out all the key themes and ideas of Moore’s work. Whereas Watchmen is a great adaptation but perhaps not overly successful as a film in its own right. And Adaptation is probably both a brilliant adaptation and a brilliant film.

One that really bugs me, though, is Atonement, since it claims to be the adaptation but fails to really understand the central theme of the book, nor does it successfully translate those ideas into the medium of film, and I don’t think the idea works as well for a film as it does for a book. I don’t know whether that means it is a lesser film or a lesser adaptation or a bit of both.

The one thing I have never understood is why filmmakers bother making an adaptation if the resulting film is going to be barely recognisable to readers of the book. If you have to change *that* much of the source material then obviously you’re trying to tell a totally different story – so what was the point of paying all that money to option it in the first place?

A great book may inspire a great film without the latter being faithful adaptation.

Blade Runner and LA Confidential superb examples of this.

Adaptation should have its own category in the art world, as the people who adapt text into film or a play into another play are effectively creating a new tale.

As long as the spirit of the original is maintained, then the adaptation works for me. I do not like social messages embedded as in the Narnia Chronicles movies that significantly altered the character of Susan and the male characters to reflect a theme that was nor originally present. It felt disingenuous to the original intent.

Don’t like it when Hollywood gets it’s hands on a novel you’ve read, enjoyed and treasured.

What is up on the screen isn’t half as good the movie in your head that played as you read the book.

The British seem to have a bit more ‘guts’ when it comes to tv adaptations.

It’s getting better in America with HBO and other production companies.

The British, and Europeans, seem to just tell it like it is.

Stage adaptions was the topic of my dissertation and I actually found it difficult to find any literature on the topic. Film adaptions – tons of literature. Made a bad choice there! I did discover that at least 50% of films are based on novels. I wonder if this has something to do with the risk of presenting something brand new and untested when such big budgets are being used. If you can prove the story already works and people like it then you have a good starting point.

I looked at His Dark Materials (National Theatre) and the work of Shared Experience as examples. The former is a trilogy that hasn’t made it to screen in full and I think theatre is a better medium to explore some of the themes in those stories. Using an existing/familiar story can provide a brilliant opportunity to try something new in terms of style and technique; of course the ultimate test is whether someone can follow the story without already knowing it.

The main thing – whatever the original source – is whether the story is any good. I’ve seen musicals that are guilty of shoehorning things in, hoping that the audience don’t mind because it’s a popular song. That isn’t good enough – it has to hold true and fit in with the world and story that’s being presented on stage at that moment.

However, everyone interprets characters in novels slightly differently so a stage adaptation can be a brilliant opportunity to do that in a more conversational way. I think a theatre production is allowed to be an interpretation whereas film is perhaps expected to give a more definitive version (unless it’s a graphic novel that’s being adapted) – and considering reading is usually an individual past time, there is no definitive version of the characters or interpretation. Theatre can play with this.

Anyway – going back to the risk thing. I did find that there was a significant rise in the number of adaptations presented during the 1980s as venues struggled with budget cuts. So it makes sense to me that we’re seeing more of them now that the sector is receiving/faced with deep cuts again…

Great theater is rare, great adaptions even harder to identify. Only one production comes to mind, it was a Steppenwolf production of The Grapes of Wrath that transferred to Broadway over twenty years ago.

Shakespeare wouldn’t be writing plays today; he’d follow the money.

I agree. If he were alive today he’d be making Michael Bay style action movies.

I like your comment.

A good adaption is as artistically viable as an original piece of work. But more than anything, I think that with adaptations it’s a case of quantity over quality – I feel the market is saturated with stories that have already been told.

I remember as a child reading Ghostbusters. It was a novel adaptation of the film. It was terrific; I was about 10.

I watched Forrest Gump again the other day. I loved the book (Winston Groom) and actually enjoyed the film a lot more this time round. Think I’d got over the needless changing of the ending.

I always thought watchmen should have been at least a miniseries. Watching the movie try and compress every iconic panel of the comic in was just so rushed. And it cut out the alternate story running through it of flashbacks and the pirates tale, so yeh I’m happy to see someone give that a go.

Lovely article. If you like football don’t go to the cricket complaining it is not more like the football. Enjoy both; life is short, appreciate art.

I’d say noir often works as both literature and cinema:

The Big Sleep

Double Indemnity

The Postman Always Rings Twice

The Asphalt Jungle

Shoot the Piano Player

Thieves Like Us

I could probably go on…

Fundamentally, a book and a film are doing different things.

Precisely, the audience comes into play as well. As sometimes a book’s audience may not correlate to that of its film adaption.

Adaptions themselves are tricky things, there is no one road to sucess. The Shawshank Redemption sticks tightly to the subject matter and is a arguably better than it’s source material, but then so is Blade Runner, which uses the book as a mere jumping off point for entirely different themes. The opinion of the author is not necessarilly an indicator either, some are uncormfortable with real changes, Stephen King hates Kubrick’s The Shining, others accept it, Chuck Palahniuk actually prefers Fincher’s Fight Club to his novel. Then there’s James Ellroy, who likes the adaptation of LA Confidential but acknowledges it tells only a small aspect of the novel.

There’s no right or wrong way here, like an original work, the primary factor for success is the talent of those involved regardless of how faithful it is or otherwise.

For me it’s the time constraints that making a movie place on what can be shown (and how much of the nuance of the events and character’s journeys can be included) in the timespan allotted to a movie – without making it an endurance event to watch. Given the nature of the medium, there is also a practical limit on how much of the character’s interior world and thinking can be protrayed – long soliloquies are so not on anymore.

An example of this is Jane Austin’s Pride and Prejudice. The BBC series had the time (and leisure) to explore the fuller nuances of events in the book than the more recent movie did. The movie completely glossed over the pivotal event (for mey, anyway) in the book where one of the younger sister elopes with the book’s ultimate “baddie” just as things are reaching for a rapprochment between Lizzy and whatisname. The BBC series was very good in showing the humiliation of the family by the younger sister’s flouting of decorum, and the appalling consequnces it could have had for the “suitability” of the rest of the girls in the family as marriage partners. Though, I thought the movie brought out the rougher and more squalid “country ways” living of the family better than the clean and sparkly family protrayed in the series.

Ultimately though, putting any piece of literature into movie form is an act of translation. Some things will have to be discarded to make things it “work” as a movie – sometimes for the better, sometimes not.

My all time favourite movie adaptation is Virginia Woolf’s Orlando – stunning film that put a different, slightly more contemporary spin on the feminist-y slant of the book. I pretty much thought the book unfilmable when I read it – props to those who made the movie version work so well.

To Kill A Mockingbird – both the film and original book are great in their stylised way.

YES! My all time favourite book is To Kill A Mockingbird, and it is also one of my all time films.

Fantastic read as always Sarai.

Can you imagine if film goers read the scripts of movies before going to the cinema? You’d still have 90% of film goers coming out afterwards whilst saying “I thought the script was better”.

Crime novels and thrillers can benefit from a movie adaptation. “The Manchurian Candidate” and “The Day of the Jackal” stripped out padding and minor characters to concentrate on the story. An overlong monster like “From Here to Eternity” is much benefited by the scriptwriter’s concentration on the main characters.

In general there’s absolutely no reason why any adaption should be inferior.

True, and yet many are inferior.

I really believe an adaptation is a whole new animal compared to the original piece. For example, when I started in film school, I was shocked at how many authors do not write their books screenplays. Why wouldn’t someone want full control over both? The truth is writing for the screen and writing for a paperback are beyond different.

I think there are so many people who are very adamant about hating a movie about their favorite book because they don’t understand that these two mediums are not sisters. They’re more like acquaintances. Now, I understand why someone would be upset. They should be. That’s the power of art.

Lovely article, especially the Romeo and Juliet case study. I love an adaption that holds true to the original text as much as the next person–but then again, as you say, there is often no such thing as an original idea. When we start remixing, modernizing and otherwise adapting adaptions–I think that’s the place where we get to have the most fun.

Great topic. I think starting with the Oxford definitions is a bit dry. It would be better to include an anecdote about a certain adaptation or even a personal experience or memory you had that involved an adaptation. The comparison between the experience of reading and that of watching a film is very potent. The use of different academic sources also makes your argument strong!

This was an incredibly insightful and well-thought our article. I️ really enjoyed reading it!

A very interesting article on a topic I have been interested in. Well written and edited at the beginning, but around a fourth of the way in many uncorrected grammatical, punctuation, and other things interfered. I also found myself agreeing less with the writer’s views on adaptions. I ended up not finishing it.

By the time I reached my teenage years I made it a rule to ALWAYS read a book before going to see the movie adaptation (e.g. Hunger Games and Fault in Our Stars). The problem with a lot of adaptations is the tendency to emphasise what they want to emphasise in the source materials- usually action and romance. Hence we get something like the hunger games movies, where the actual message of rising against the rich and empowered by the poor, by people of colour, by disabled people, gets completely lost in the Capitol-themed makeup kits and the people who are too lost in the question of which boy Katniss will fill out the baby boomer dream of making pretty little babies with to remember that in the books she was a WOC, she and Peeta were both physically disabled and traumatised- Rue is reduced to a footnote- all the things that apply to our current world and Actual Real Problems (i.e. the things that made the books relevant and good). I can live with awkward script, or if they give a plot role to a different character to move things along. It’s when the actual themes and ideas of the material is lost for marketability or to make the film ‘more interesting’ that I leave the theatre bitter.

One of the best adaptations of a book was recently screened at the Tribeca Film Festival. Jeremiah Zagar’s We the Animals is a brilliant celluloid take on the prize-winning 2012 novel by Justin Torres. The two works enhance each other to an amazing degree. You watch the film, then you want to read the book, then you want to rewatch the film, and so forth. This tale of poverty, brutality, race, brotherly love, and coming out strikes a chord that you won’t want to be silenced. Too bad you can’t overlay one work on the other and experience them simultaneously.

Very educational and clarifying. I struggle to not judge an adaptation based on the original. This has opened my eyes and I will try to be open-minded toward them.

Fantastic article! Thank you for mentioning Pocahontas. Adaptations of one art form to another are one thing, but adapting real-life occurrences can be trickier, especially when representing marginalized communities. Artists need to practice respect and authenticity when tackling such projects.

What is the point of adaptation if there are not going to be changes? Isn’t that what makes an adaptation what it is?

Awesome article. Really shows what adaption can really mean from the perspective of producers and audiences alike, and just how complicated the art of adaption really is. I hope more people can begin to understand that too! ☺️

Adaptation is such a tricky topic, liable to make everyone mad, at some point. I liked your dexterous handling of these often thorny issues and questions. There really are no easy answers. For myself, I find I don’t mind loose adaptations of fairy tales (considering their multitudinous variation) or frankly mediocre novels/stories, but the better something is the trickier the issue becomes (though as regards fairy tales, I think even the darker ones can be more nuanced than most people assume). At bottom, I think, even if you veer widely off from the narrative events of your source material, it is important to respect the major themes of the work, and what the author was attempting to convey (hence, my hatred of Frozen). But again, a thorny issue deftly handled.

Adaption is the corset of narrative structure.

I think there is a difference between adapting a story and adapting a real historical event. I think if it is based on a real event, it is important to capture it realistically as possible or not even relate it to that event. As a teacher, I see students assimilate these incorrect views of history, rather than the facts as we know it.

Concerning story, however, I think most stories build upon the foundations of other stories. Think of the influence of Greek mythology which is referenced in thousands of stories. Fairy tales themselves are always adaptations of the stories that traveled and were changed according to their own culture. For example, the original Cinderella story can be traced back to China, hence the small feet reference.

Story is always reflective of what culture values and should be understood in that light. Story, like language, is always changing. It is because of this that we should read books from many different time periods as it helps us to have a broader view of the world.

I don’t think you can use the term ‘adaptation’ when you are dealing with historical events, except when you are taking written source material about an historical event and turning it into film or TV (e.g. *Band of Brothers* was adapted from the book into the miniseries).

If I pick an historical event to make a movie about, I’m not really adapting anything. It’s a thing that happened and I can choose to write a story that either faithfully retells it or create a new work that is inspired by the real events (or something in between). Adaptation implies transferring the story between mediums.

The rest of your comment is spot on, though. I always think it’s interesting to read older books and see how much of the cultural values of the time shine through in the writing, and to what degree authors were able to innovate and be progressive in their writing as opposed to being bound by their contemporary values.

There has to be some element of adaptation though, even for an historical event. For one, our understand of history is always subjective, gleaned mostly through the observations of participants who are subjective themselves. Then, in the making of any medium, the director must fit the story into a narrative arc, deciding what elements to emphasize and which to ignore. There will never be s completely accurate rendering of an historical event unless we could somehow gain the perspective of everyone involved.

I love adaptations just as much as originals. I think adaptations can enhance aspects of the original previously unnoticed to the audience. Adaptations can also linger on enjoyable aspects of an original piece for the audience to soak in. Different senses are stimulated through the different mediums of one text and can result in a wonderfully complete picture in one’s mind when done right.

Brilliant analysis and great writing. Adaptation is within my field of study and I can tell you that you didn’t disappoint in your overview. I’d recommend this article to anyone who is new to the concept of adaptation!

Great article on adaptation! In my experience, I’ve often found that adaptations are much better than the source material. As a literature major I feel guilty of sometimes enjoying the films more than the books, but as a writer I realise that the art of adaptation allows for a more universal experience and connection to the story.

I see adaptation, at the most basic level, as a tool to reestablish/reconnect a story/moral/ set of values with a current society.

A perceptive essay. How you addressed Disney films I found quite good.

If you read some of the lesser-known Grimms’ Fairytales, you can see why they have the dark reputation that they had.